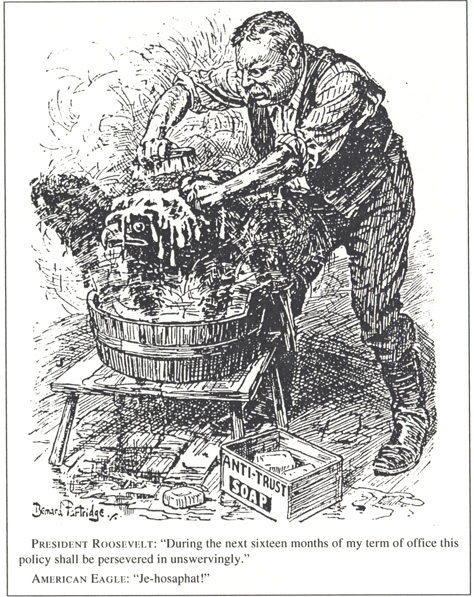

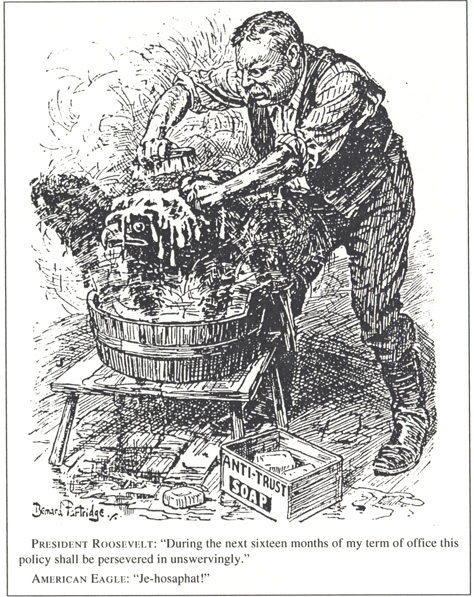

“The Soap-and-Water Cure,” Bernard Partridge, Punch.

At a political rally on an island in Lake Champlain, TR first heard the news that McKinley had been shot. Reassured at first that the president was out of danger, TR traveled with his family to the Adirondacks for vacation. There, while picnicking beside a brook, TR saw a runner dart toward him, out of the woods. “I instinctively knew,” TR said, “he had bad news, the worst news in the world.” Shortly after, another message followed. McKinley had died.

On his way home from McKinley’s funeral, Republican senator Mark Hanna was in despair. “I told William McKinley it was a mistake to nominate that wild man at Philadelphia,” he fumed. “Now look, that damned cowboy is President of the United States!”

The new president was not yet forty-three, the youngest man ever to fill that office. As the shock of the assassination reverberated across the land, TR’s first instinct was to calm the roiled waters and hold steady the ship of state. He kept McKinley’s cabinet intact—easy to do since Secretary of State John Hay and Secretary of War Elihu Root were close friends, and Secretary of the Navy Long appeared perfectly happy now to have his former protege as his new boss. Roosevelt also indicated that he would carry on McKinley’s policies—for a time. “It is a dreadful thing to come into the Presidency this way,” he wrote Lodge, “but it would be a far worse thing to be morbid about it.”

But TR’s fiery temperament—and the course of events—would not permit him to be nothing more than McKinley’s fill-in. An exuberant, ebullient, expansive force of nature had entered the White House, along with his wife, six children and assorted pets, plus bicycles, tennis rackets, and roller skates.

A few weeks after assuming office he took a step—perhaps ingenuously, perhaps calculatingly, more likely both—that aroused a roar of indignation and controversy across the land. He invited the educator Booker T. Washington, the leader of African-American Republicans in the South, to dine at the White House. The president, some Southerners cried, was encouraging dangerous ideas of racial and social equality, and hence unrest and disorder. Roosevelt’s reaction to the reaction was revealing. He found the burst of feeling in the South “literally inexplicable,” he wrote a friend. It did not anger him, but he was “very melancholy that such feeling should exist” in any part of the country. A few days afterward he was blaming the “idiot or vicious Bourbon element of the South.” Later he rationalized that, as things turned out, “I am very glad that I asked him, for the clamor aroused by the act makes me feel as if the act was necessary.”

Warned that he might alienate southern delegates to the 1904 nominating convention, he stood his ground. “I would not lose my self-respect by fearing to have a man like Booker T. Washington to dinner if it cost me every political friend I have got,” he wrote. But never again did he invite a black man to dine at the White House. Similarly, in 1902, TR decided that his nominee for ambassador to Germany, George von Lengerke Meyer, a Boston Brahmin who was the ambassador to Italy and later ambassador to Russia, would not receive “social recognition” in Germany because of the erroneous and “strange belief” that he was of Jewish origin, and so he nominated someone else.

Theodore Roosevelt was a political leader still in transition. In his first decade or two as a politician he had appeared to be a “good-government reformer,” focusing largely on ways to purify politics through civil service reform: curbs on Tammany and other bosses, attacks on corruption, and cutting down patronage jobs. To some degree during his police com-missionership, and to a much greater degree during his governorship, he had had to confront the needs for economic reforms, especially in the regulation of business. While flatly hostile to any kind of revolution or violence, he did welcome change and was becoming more and more open to the idea of government intervention to help labor and the poor and to regulate big business.

Some doubted the sincerity of his commitment to reform. They noted that he had sided with the “regulars” at every critical political junction, that he hobnobbed socially with the rich, that he still practiced the elitism of a “Porcellian man,” that he favored only superficial reforms, that for all his sermonizing about democracy he was lukewarm on women’s right to vote, and that he was more patronizing than helpful to the causes of African-Americans and certainly American Indians. He believed in doing things for people, it appeared, not with them, and for reasons of duty, not empathy.

The New York press establishment also doubted that TR would bring about real change. Roosevelt was in “perfect sympathy” with McKinley’s “triumphant policies,” commented the New York Tribune. The temper of his mind would hardly incline him to “more shining glory” than that of his predecessor, said the Times. The Sun had reasons why he would be as prudent and sagacious as McKinley, explaining that Roosevelt’s “political future, his whole reputation, depend on his fidelity to the sentiment of his party.” Fortunately, he was a “strict party man,” and his policies would not “depend on the possible vagaries of an individual judgement.”

They hardly knew their man.

Just what causes political landscapes to change, old elites to fall and new leaders to rise, in a nation’s capital and across the country? Superficially, the 1880s and 1890s might have seemed to be an era of relative political and ideological calm, as respectable Republicans—Chester A. Arthur, Benjamin Harrison, and William McKinley—alternated in national office with the respectable, conservative Democrat Grover Cleveland. And superficially it might have seemed that burgeoning middle class Americans, as they achieved social status and some economic independence, were increasingly complacent and conservative as they began to move out of the brawling cities into nearby suburban areas.

But beneath the surface, a middle-class revolt was germinating, one that would explode after the turn of the century. It was not a revolt of the masses—in America the masses were too suppressed and divided to rebel—though workers and immigrants, along with professional elites and church leaders, and middle-class Americans, helped energize the movement.

Was the uprising triggered by new political ideas? By the radical presidential campaign of William Jennings Bryan? By the emergence of the progressive Robert La Follette in Wisconsin?

Or was it ignited by the depression of 1893-97, years of hardship that dramatized some of the country’s problems, making people more resentful of the conspicuous consumption of the wealthy, more irate about mega-corporations and monopolies? Unemployment had reached 20 percent across the nation; in 1894 alone there were 1,394 strikes, including the famous Pullman strike that ended when President Cleveland sent in federal troops. In 1894, one Ohio businessman, Jacob Coxey, led a group of 500 unemployed men to Washington, demanding federal public works projects, only to be beaten and arrested on the steps of the Capitol. “Up those steps the lobbyists of trusts and corporations have passed unchallenged,” fumed Harper’s Weekly, furious that “the representatives of the toiling wealth-producers have been denied.”

Was these Americans’ sense of social justice awakened by the Social Gospel movement, which called on churches and church members to help the underprivileged of society, or by the proliferation of settlement houses that the Social Gospel movement inspired? By a new army of social workers, by calls for child labor laws, better schools, playgrounds, factory inspection, and regulation of working hours?

Was the sense of revolt galvanized by a meeting that took place in Buffalo in 1899? The National Social and Political Conference—attended by some reform mayors along with Samuel Gompers, head of the American Federation of Labor; Henry Demarest Lloyd; Eugene Debs, the socialist chief of the American Railway Union; and others—agreed on a program that called for more direct popular control over government, more equitable forms of taxation, public ownership of public utilities, and regulation of the trusts.

While the Buffalo meeting led to no lasting organization, other nationwide groups were emerging. Dotting the landscape were the National Consumers’ League, the National Child Labor Committee, the National Housing Association, the American Association for Labor Legislation, the Committee of One Hundred on National Health, and many other organizations.

Was it a revolt partly encouraged by reform legislation passed by Congress—the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 and the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890—along with social legislation passed by states, setting housing standards and regulating workers’ hours, child labor, factory safety, and working conditions? People were awakening to the realization that desperate poverty was not, as Mugwump Francis Parkman had asserted, a function of “an ignorant proletariat,” but rather the inevitable result of a variety of social and economic conditions, ranging from gross inequities in the tax system and inadequate and unsafe public transportation to child labor.

Or was the revolt inspired by Theodore Roosevelt’s ebullient leadership? Perhaps to some degree, but Henry George had already been writing about poverty, Edward Bellamy about an egalitarian Utopian world, Charles Sheldon about the morality of business, and Henry Demarest Lloyd about the sins of the Rockefellers and other capitalists—while TR was still politicking in New York.

Perhaps the seeds of revolt were planted and nurtured by journalists and other writers, who often viewed themselves as members of an economic proletariat. Time was, the author Finley Peter Dunne’s satirical character “Mr. Dooley” observed to his friend Mr. Hennessy, when magazines were calming to the mind. “But now whin I pick me fav’rite magazine off th’ flure, what do I find? Ivrything has gone wrong … Graft ivrywhere. ‘Graft in th’ Insurance Complies,’ ‘Graft in Congress,’... ‘Graft be an Old Grafter,’ ... ‘Graft in Its Relations to th’ Higher Life.’”

Far more than the subject of old-fashioned graft now took the place of entertaining travel stories and escapist romances in the nation’s magazines and novels. Edward Bok denounced patent-medicine evils in the Ladies’ Home Journal, Thomas W. Lawson crooked finance in Everybody’s, David Graham Phillips “The Treason of the Senate” in Cosmopolitan. In McClure’s, Lincoln Steffens dramatized the “Sharnelessness of St. Louis,” the “Defeated People” of Philadelphia, the “Hell with the Lid Lifted” of Pittsburgh. Ida Tarbell, whose father had been forced out of business by Rockefeller, wrote a blistering series of articles for McClure’s on the corrupt business practices of Standard Oil. Stephen Crane depicted abject urban existence in his novel Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, while Frank Norris exposed exploitation in the railroad industry in The Octopus. W. T. Stead penned If Christ Came to Chicago. Most arresting of all was a novel, The Jungle—Upton Sinclair’s horrifying portrait of conditions in the meatpacking industry. These works and a host of other exposes by America’s first large stable of investigative reporters aroused middle-class anger to a peak.

These were the muckrakers—investigative reporters, journalists, novelists—who were shaping progressive opinion. Yet the term “progressive” is problematic, for the progressive movement was, in truth, protean, contradictory, and almost indefinable, and the word itself was not much used until 1909.

Still, between the 1890s and 1920, the United States was swept by powerful calls for progressive reform. Every level of government was involved, from local and state to national; every dimension of civic life was involved, from religion to women’s rights to conservation. Progressive wings existed in both major parties. The movement was weakest in New England and in the South, strongest in the Midwest and West.

Unlike the Mugwump reformers of the 1880s, the new progressives desired popular government, not government by the elite—although, like their Mugwump forebears, the progressives too resented the swollen wealth of the plutocrats and the private unaccountable power of the trusts.

But progressives were divided as to the remedy. Some desired a return to the old laissez-faire competitive system; others favored government regulation of corporations. On foreign policy they were also divided. Those in favor of laissez-faire tended to advocate American isolationism; those pushing for government regulation also saw a strong role for government in international affairs. Progressives differed on policy toward immigrants and immigration, toward labor and unions, and toward Prohibition. Taking up the progressive banner were those who sought efficiency and clean government only to insulate government from more meaningful reform. And whereas a progressive like Robert La Follette, who became the Republican governor of Wisconsin in 1900 and helped make his state the “laboratory of democracy,” was passionate about social justice, he could simultaneously be nostalgic for the nineteenth-century sense of community. The one thing that virtually all progressives agreed upon was race: racism and the suffering of black Americans were simply not on their agenda.

So divided were progressives that some historians suggest discarding the terms “progressive” and “progressive movement,” while others discern, underlying all the divisions, a progressivism that was a real movement of modernization, bringing together a coalition that cut across class, economic, religious, and ethnic barriers and led to concrete results. Indeed, unifying progressives was a commonly held and galvanizing sense of moral responsibility for the public good. A new spirit of sacrifice, commented newspaper editor William Allen White, seemed to be overcoming the spirit of commercialism. Appearing on the scene was a nationwide army of young men, wrote White, whose “quickening sense of the inequities, injustices, and fundamental wrongs” in American society motivated them to join the progressive reform movement.

Theodore Roosevelt’s voice and intensity, more than any concrete results he might have obtained, spoke to these people. At the turn of the century, Republican leaders acknowledged that TR, in the words of historian Lewis Gould, “possessed a hold on the public mind.” Prizing social order above all, eager to avoid upheaval and class warfare, the unpredictable Roosevelt bent to the winds of progressive public opinion. To a progressive movement that was turbulent and unfocused, TR brought his sense of practicality, his respectability, his national authority. Little by little he would come to possess a “spiritual power,” William Allen White remarked years later about his hero. “It is immaterial whether or not the Supreme Court sustains him in his position on the rate bill, the income tax, the license for corporations, or the inheritance tax.” What seemed to matter to a generation of progressive reformers was that “by his life and his works he should bear witness unto the truth.”

“Teddy was reform in a derby,” said White, “the gayest, cockiest, most fashionable derby you ever saw.” But some reformers saw it as more of a silk hat.

...

The burning issues were wealth and power. Who ran the United States? The federal government, in the name of the supposedly sovereign people, or the industrialists, bankers, and financiers? Was the government merely their “satellite”? Free enterprise and economic individualism were, for many, the American religion, not only economically correct but socially and morally valid. Millionaires were the product of natural selection, argued the expounders of laissez-faire capitalism. Furthermore, they held, neither the rich nor the poor should receive aid from government. “The Government must get out of the ‘protective’ business and the ‘subsidy’ business and the ‘improvement’ and the ‘development’ business,” wrote the Mugwump E. L. Godkin. The government’s job, insisted these laissez-faire Spencerians, was solely to maintain order and administer justice.

Justice for whom? In 1888, President Eliot of Harvard pointed out that while the Pennsylvania Railroad had receipts of $115 million and employed 100,000 people, the state of Massachusetts had receipts of $7 million while employing 6,000 people. In that same year, Edward Bellamy wrote the runaway best-seller Looking Backward, the story of a young Boston millionaire who falls asleep in 1887 and wakes up in the year 2000, in an orderly, affluent, egalitarian Boston bearing no resemblance to the cruel, class-ridden, and altogether bleak city of the late nineteenth century. Looking back on his earlier life, he recalls “living in luxury, and occupied only with the pursuit of the pleasures and refinements of life, [deriving] the means of my support from the labor of others, rendering no sort of service in return.”

Like Bellamy, TR would also attack the idle rich, the “fashionable” society of nouveaux riches who had no interest in civic affairs, no sense of responsibility for the body politic, no philanthropic commitments. The nouveaux riches were displacing the “polite” society of old Dutch families like his own. Men of “mere wealth” were, he judged, both a “laughingstock and a menace to the community.” Venting his “contempt and anger for our socially leading people” a month before McKinley’s assassination, he confessed to a friend that he felt nothing but scorn for the “ineffective men who possess much refinement, culture, knowledge, and scholarship of a wholly unproductive type,” for they “contribute nothing useful to our intellectual, civic or social life. At best, they stand aside.” The spectacle of their lives at Newport varied only “from rotten frivolity to rotten vice.” Indeed, TR would go so far as to prevent a British fleet in 1905 from making its usual stop in Newport, so contemptuous was he of “the antics of the Four Hundred when they get a chance to show social attentions to visiting foreigners of high official positions.”

But there existed, for TR, two other categories of wealthy people. The first was the one in which he placed a few men like himself and his friend Henry Cabot Lodge, men in public service who were able to make a contribution to society thanks to their inherited wealth. “Each of us has been able to do what he has actually done because his father left him in such shape that he did not have to earn his own living. My own children,” TR acknowledged, “will not be so left.” The second class was that of powerful men, like J. P. Morgan, “who use their wealth to full advantage.”

Though TR was disgusted by the idle rich, the kind of people with whom his brother had socialized and hunted on Long Island, they had become irrelevant. As he had noted, now they willingly stood aside, displaced by a new class of capitalists. Analyzing this displacement of one capitalist class by a newer, more dynamic one, the historian Henri Pirenne argued that when there is a change in economic organization, often the old capitalists cannot adapt to the new conditions. Instead, they withdraw from the struggle to become a passive aristocracy. In their place arise new men, courageous, innovative, and enterprising.

Repelled by the leisure class, TR breezily abandoned them with disgust and contempt. But it would be a more serious and complex challenge to take on the new aristocracy, that of coal barons, steel kings, railroad magnates, cattle kings, and Napoleons of finance. “It is useless for us to protest that we are democratic,” Josiah Strong had written in 1885. “There is among us an aristocracy of recognized power, and that aristocracy is one of wealth.” Indeed, in just one generation the new plutocrats had sprung into seats of power that even kings had not dreamt of. So wrote Henry Demarest Lloyd, author of Wealth Against Commonwealth. New conditions and altered circumstances of society had rendered possible the “creation of new privileges and pretensions for those who were energetic and alert.”

As president, TR’s goal would be to regulate and restrain this new capitalist caste, this new plutocracy. In his autobiography, he admitted that, as president, it took him a considerable amount of time before “going as far as we ought to have gone along the lines of governmental control of corporations and governmental interference on behalf of labor.” But, little by little, TR would evolve from the mild regulator of megacorporations and the neutral umpire in labor-management disputes that he was during his first term to—in the last year of his presidency and beyond—a militant foe of those he called “representatives of predatory wealth” and a committed supporter of the rights of labor.

President Roosevelt’s first target was the trust—and what he called the “deep and damnable alliance between business and politics.” Though the Sherman Antitrust Law had been passed in 1890 in reaction to the formation of the tobacco trust and the sugar trust, President Cleveland used the act to prosecute labor leader Eugene Debs on the grounds that union organizers were acting in restraint of trade. Although more trusts were formed during McKinley’s presidency than ever before, McKinley had brought only three antitrust suits. And in the wake of the Knight case—the Supreme Court’s decision in 1895 not to break up the sugar trust on the grounds that it was engaged in manufacturing and not in commerce—trusts were proliferating all over the American economic and industrial landscape. In addition to Andrew Carnegie’s United States Steel Corporation and John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil—which controlled iron as well as oil—there were also the National Biscuit Company’s food trust, a leather trust, a life insurance trust, a beef trust, and a concrete trust. The Supreme Court, TR fumed, was upholding “property rights against human rights.”

But now the business world was worried. What would be the policies, Wall Street fretted, of the “bucking bronco” in the White House? Even before TR had been sworn in as president, business leaders had pressured his brother-in-law, Douglas Robinson, to urge Roosevelt to toe a pro-business line. “I must frankly tell you,” Robinson wrote to TR, “that there is a feeling in financial circles here that in case you become President you may change matters so as to upset the confidence... of the business world.” Mark Hanna agreed. “Go slow,” he cautioned.

Five weeks into Roosevelt’s presidency, a huge trust was incorporated, J. P. Morgan’s Northern Securities Company. Convinced that competition was wasteful, Morgan created this “holding company” type of trust, combining stock in three railroads, the Northern Pacific, Union Pacific, and Burlington, as well as shipping interests. TR feared that a small group of financiers had taken “the first step toward controlling the entire railway system of the country.”

In TR’s first message to Congress, in December 1901, he congratulated the titans of American business for their supremacy in the world, but he also warned of the “real and grave evils” that stemmed from “overcapitalization.” As president, he proposed that the federal government exercise control of corporations and that, if necessary, a constitutional amendment enabling it to do so be passed. Corporations were necessary, he maintained, but they must be “beneficial to the community as a whole.” In a speech in Providence, Rhode Island, TR declared that while the poor were not necessarily growing poorer, the rich were growing so much richer that the contrast struck one violently. Later he would criticize a “riot of individualistic materialism” accompanied by a complete “absence of governmental control.”

Despite the warnings he had received, TR charged ahead. He first confronted the formidable J. Pierpont Morgan himself. Bypassing his cabinet, Roosevelt in great secrecy instructed his attorney general, Philander Knox, to move against Morgan and the Northern Securities Company on grounds of conspiracy in restraint of trade, in violation of antimonopoly laws.

A commanding personality with his huge flaming red nose, piercing eyes, and beetling brows, Morgan, having just bought out Carnegie and other steelmakers to put together the nation’s first billion-dollar corporation, radiated economic power. He had, moreover, bailed out the Cleveland administration in 1894. During a rush on the U.S. treasury’s gold supply, Morgan and August Belmont Jr. purchased 3.5 million ounces of gold. Afterward, Morgan considered himself the head of a “fourth branch” of government.

Now Morgan was indignant. Hadn’t he given TR $10,000 when he ran for governor? Why, he had even supported TR for reelection to the New York Assembly back in 1882! As for TR, as vice president he had hosted a dinner for Morgan at the Union League Club. (The dinner, TR had confided—perhaps tongue-in-cheek—to Elihu Root, “represents an effort on my part to become a conservative man, in touch with the influential classes.”) Thanks to the young president, Morgan had received, Henry Adams gleefully reported to a friend, a “tremendous whack square on the nose.”

Morgan felt that the only way to resolve their differences was a friendly talk among gentlemen—after all, both he and TR belonged to the old gentry. Confronting the president in the White House, he offered an olive branch. “If we have done anything wrong, send your man”—Attorney General Knox—“to my man and they can fix it up.”

“That can’t be done,” the president said. He would not attack any of Morgan’s other interests—“unless ... they have done something that we regard as wrong.” Morgan viewed him, the president reflected later, as simply a big rival operator. But for TR it was a heroic joust, between the young president, champion of the people as well as of responsible wealth, and the the plutocrats, men of “swollen fortunes” whom he labeled “predatory capitalists.” These reactionary “Bourbons,” according to TR, “oppose and dread any attempt to place them under efficient governmental control.”

TR really wanted government regulation of the trusts, not their dissolution, for he was convinced that dissolution would have meant a return to a nineteenth-century rural economy. What was called for was legislation to “protect labor, to subordinate the big corporation to the public welfare, and to shackle cunning and fraud.” But a recalcitrant Congress was not about to pass regulatory measures that were opposed by intransigent business leaders, and so TR was thrown back on the Sherman Antitrust Act as his only alternative. In any case, he felt strongly that the core issue was not the method by which the government would control the trusts but, more fundamentally, whether the government had the power to control them at all.

Two years later, in March 1904, the Supreme Court upheld the government’s action against Morgan’s Northern Securities. TR considered this one of the great achievements of his administration, proud that the case demonstrated “the fact that the most powerful men in this country were held to accountability before the law.” In the wake of his victory, he brought suits against the American Tobacco Company, Standard Oil, Du Pont, the New Haven Railroad, the beef trust, and forty other trusts, crediting his three attorneys general, Philander Knox, William Moody, and Charles Bonaparte, with fearless perseverence. Standard Oil and the tobacco trust were eventually ordered dissolved. Even so, TR, still preferring regulation to dismantlement, felt that the government had asserted its power to curb monopolies but had not yet devised the proper method of exercising that power.

...

Another test of TR’s leadership loomed: the coal strike.

In the spring of 1902, 147,000 anthracite coal miners walked out in northeastern Pennsylvania, a bleak land reeking of the sooty smell of coal dust, crisscrossed by coal trains running through “on loud rails”—a land where, in the words of poetjay Parini, miners chipped away in the “world’s rock belly.” In the mine shafts, explosions and cave-ins maimed hundreds, killing six men out of a thousand every year. Most miners were ravaged by asthma, bronchitis, chronic rheumatism, tuberculosis, or heart trouble. By the age of fifty, many were broken.

The major coal operators, who also owned six railroad corporations, were refusing to discuss a wage increase with John Mitchell, president of the United Mine Workers. Despite their own sizable annual income raises, the operators would not decrease working hours or make any other concessions to the miners’ union. Coal was a business, reasoned George F. Baer, president of the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Company and the industry’s spokesman, noting that if wages went up, prices would also have to go up. But even more important than controlling wages and prices, Baer wanted to break the back of the United Mine Workers and its young president. “There cannot be two masters in the management of business,” he declared. The operators claimed that they would deal with their own workers but not with the union representatives, whom they denounced as criminals. Though some independent mine operators wanted to reach a settlement with the union, they were prevented from doing so by the six great railroads.

Coal was the major source of heating in the country, and, as the strike continued through the summer and the price of coal almost tripled, alarm was rising. In September, with schools in New York closing to conserve fuel, fear of a cold winter gripped the city. The patrician mayor of New York, Seth Low—the former president of Columbia University—wired President Roosevelt, urging that mining be resumed “in the name of the City of New York.” In the face of growing public anxiety, the mine operators were giving the impression, at least to some people, of being recklessly indifferent to the welfare of the nation.

But the operators were acting on deeply held principles. In a letter to a citizen in Pennsylvania who had urged him to end the strike, Baer expressed his belief that workers did not need unions and that employers did not need to recognize them. Workers would be protected sufficiently by the “Christian men to whom God in His infinite wisdom has given the control of the property interests of the country.” The letter was quickly leaked to the country’s newspapers, which had a field day capitalizing on the arrogance of big business. The New York American and Journal attacked the “thieving trusts.” The New York Churchman, an Episcopal paper, called Baer’s letter “blasphemy.” A Baptist paper in Boston, the Watchman, wrote that “the doctrine of the divine right of kings was bad enough, but not so intolerable as the doctrine of the divine right of plutocrats.”

What would the president do? Would he send in federal troops to crush the strike and open the mines? Presidents before him would have done no less. Rutherford Hayes had intervened in the general railroad strikes in 1877, sending federal troops to restore order in Martinsburg, West Virginia, and in Pittsburgh. In 1894, when the American Railway Union, under the leadership of Eugene Debs, struck all Pullman cars, paralyzing the industry, President Cleveland sent federal troops to restore order; Debs was jailed, and the strike was smashed. “We have come out of the strike very well,” TR had then written approvingly to his sister. “Cleveland did excellent.” The president and attorney general had acted with “wisdom and courage,” while the governor of Illinois, who had wavered, was a “Benedict Arnold.”

There was little reason to imagine TR more sympathetic to strikers than Hayes and Cleveland. About fifteen years earlier, when news had reached TR of the Haymarket Massacre, in which seven policemen were killed and seventy others wounded following a labor meeting in Chicago, he had expressed no sympathy for the claims of labor. Writing to his sister from the Badlands, he had commented on the difference between the real American men out west and the anarchic strikers in Chicago. “My men here are hardworking, labouring men, who work longer hours for no greater wages than many of the strikers,” he wrote, adding that “they are Americans through and through; I believe nothing would give them greater pleasure than a chance with their rifles at one of the mobs.”

But now TR was faced with a strike of his own. Engineers, firemen, and pump men joined the coal miners in the largest national work stoppage up until then. The strike dragged on, week after week, punctuated by violent clashes between strikers and nonunion men who wanted to go down into the mines. The nation’s newspapers—some attacking the coal operators, others whipping up antiunion feelings—were demanding an end to the work stoppage. Princeton University’s new president, Woodrow Wilson, suggested that the real issue in the strike was the union’s unhealthy drive “to win more power.”

In August, TR briefly considered bringing antitrust proceedings against the coal operators under the Sherman Antitrust Act. “I am at my wits’ end how to proceed,” he wrote. But in October he called the miners and operators to a meeting, urging an immediate resumption of operations. John Mitchell stood up and, in the name of his workers, accepted the idea of an arbitration board to resolve the strike’s issues. But Baer categorically rejected such a board, refusing to “waste time negotiating with the fomenters of this anarchy.” On the contrary, he demanded that federal troops be sent in and that the union be prosecuted. Throughout the depressing daylong conference, TR noted, only one man had behaved like a gentleman “and that man was not I.”

“I have tried and failed,” the tired president sighed. But encouragement arrived from an unlikely source. Grover Cleveland, the former president, admitted that he was “disturbed by the tone and substance of the operators’ deliverances.” Now, with the support of this antilabor conservative, TR could look for another way out. One solution he did not entertain was calling in troops to quash the union. Although he wrote to a friend that “the preservation of law and order would have to be the first consideration,” in truth, merely restoring order was not his top priority.

TR began to conceive of himself as a neutral umpire representing the public interest. The titans of business, he bristled, forget that they “have duties toward the public.” A few days later he explained that the turbulence and violence that some people feared from the strike were “just as apt to come from an attitude of arrogance on the part of the owners of property and of unwillingness to recognize their duty to the public as from any improper encouragement of labor unions.” His conclusion? The public did indeed have its own “rights in the matter.”

Accordingly, TR no longer viewed the production and distribution of coal as a private business. “I feel most strongly,” he wrote to Mark Hanna, “that the attitude of the operators is one which accentuates the need of the government having some power of supervision and regulation over such corporations.” TR’s plan was now to take over the mines and run them in a kind of receivership. He had decided to take strong action, rejecting out of hand the idea of looking for “some constitutional reason for inaction.” When one congressman objected that the Constitution did not permit the government to seize private property without due process, TR snapped, “The Constitution was made for the people and not the people for the Constitution.”

He chose Major General J. M. Schofield and asked him to be ready to follow orders to dispossess the operators and run the mines. Next he asked Senator Quay of Pennsylvania to inform the governor of that state that TR would like him to request that the president send in federal troops. TR wanted Quay to assume—as Quay did—that the troops would be used to keep order only. According to the plan, when he was ready, TR would give Quay the signal.

But in the meantime, Secretary of War Elihu Root paid a visit to J. P. Morgan in New York, informing him of the plan but hoping to enlist the great financier’s intervention in setting up an arbitration commission. Root and Morgan, who had always favored negotiations, composed a memorandum urging Baer to accept arbitration with the anthracite miners. Hurrying to Washington, the next day Morgan himself presented TR with a document signed by the six operators accepting an arbitration commission.

But once again the operators proved recalcitrant, refusing to include a union representative on the commission and even refusing a spot for President Cleveland. TR exploded; the operators were stupid and obstinate, he sneered, mired in the “narrow, bourgeois commercial world.” Suddenly TR devised a solution. On the commission there was a place for a “sociologist,” and to that seat he appointed a union representative. The idea of labeling a labor leader an “eminent sociologist” was, TR scoffed, an “utter absurdity” but one that everyone received with delight. “I at last grasped the fact,” he wrote, “that the mighty brains of these captains of industry had formulated the theory that they would rather have anarchy than tweedledum, but if I would use the word tweedledee they would hail it as meaning peace.” To his friend Finley Peter Dunne, author of Mr. Dooley’s political observations, TR confided that “nothing that you have ever written can begin to approach in screaming comedy the inside of the last few conferences.”

“My dear Mr. Morgan,” TR wrote, soon after the strike was ended, “let me thank you for the service you have rendered the whole people. If it had not been for your going into the matter I do not see how the strike could have been settled at this time. I thank you and congratulate you with all my heart.”

In Cambridge, Massachusetts, a future president of the United States did not approve of the settlement. “Now that the strike is settled the coal has begun to come in small quantities,” Harvard student Franklin Roosevelt wrote to his mother. “In spite of his success in settling the trouble, I think that the President made a serious mistake in interfering—politically, at least. His tendency to make the executive power stronger than the Houses of Congress is bound to be a bad thing, especially when a man of weaker personality succeeds him in office.”

The miners had returned to work, and five months later an agreement was reached. Miners’ wages went up 10 percent, the workday was reduced to nine hours, in some cases eight, and many of management’s flagrant abuses were corrected. Finally, an anthracite board of conciliation was set up, though the operators had still not officially recognized the union.

In his confrontation with Northern Securities, as in his role in the coal strike, the president was challenging the private power of industry, making the government a third party in labor-management disputes and superior to the two other parties. Conservatives were horrified that the president had dared to interfere with the sacred ideology of free entreprise and laissez-faire capitalism. Though TR’s wily stratagem for ending the coal strike fell short of John F. Kennedy’s energetic mobilization of the whole executive branch to force the steel industry to roll back a price increase, in the context of his own times TR had struck a new note.

The government would play an active role, yet the role, as TR conceived it in the early years of his presidency, was “neutral,” a mild one. The government would be umpire, defending the interests of the nation as a whole. “I am President of the United States,” TR proclaimed, “and my business is to see fair play among all men, capitalists or wage workers.” But such a neutral stance often favors the status quo. In 1903 TR sent federal troops to put down a strike in Arizona territory and, the following year, refused to send troops to protect mineworkers under attack in Colorado.

TR had not yet reached the point in his presidency and his moral development that would lead him to believe, as he later wrote in his autobiography, that government “must inevitably sympathize with the men who have nothing but their wages, with the men who are struggling for a decent life,” as opposed to those who are “merely fighting for larger profits and an autocratic control of big business.”

...

In his third year in the White House, Theodore Roosevelt took a step that would profoundly influence American foreign policy—and ultimately world history—during the twentieth century. In this case he did not grab some real estate or start a war but, instead, issued a statement, the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. That corollary, announced in reponse to the threat of German invasion of Venezuela and foreign creditors’ intervention in the Dominican Republic, transformed the doctrine from a mere safeguard against intervention by European powers in Latin America to a presidential decree establishing the right of the United States to intervene. Like many presidential decrees in the following century, this doctrine was never formally ratified by the Senate, endorsed by the American people, or even cleared with foreign governments, friendly or hostile.

“If a nation shows that it knows how to act with decency in industrial and political matters, if it keeps order and pays its obligations, then it need fear no interference from the United States,” Roosevelt stated, but “brutal wrongdoing, or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties of civilizing society, may finally require intervention by some civilized nation; and in the Western Hemisphere the United States cannot ignore this duty.” These words bespoke TR’s key ideas: his moralizing, his fear of weakness, his respect for “civilized” nations, and above all his insistence on law and order. The very elasticity and vagueness of these values would open door after door for United States interventions abroad.

Washington’s practice of intervention was of course nothing new. For decades the “Yankees” had been preaching their values to Latin America and backing them up with threats, dollars, and gunboats. Roosevelt himself had fought in a war that not only drove Spain out of Cuba but also out of the Philippines and Puerto Rico, leaving the United States with responsibilities in those lands—especially the Philippines—that became difficult to fulfill. Washington’s insistence on nonintervention by European nations was so strong and continuous that Britain abandoned its claim to a major role in Central America.

If the practice of Yankee intervention was not new, TR’s explicit defense and promulgation of it was. Equally clear was his insistence that he was taking on this burden neither out of “land hunger” nor out of antagonism to the other powers. On the contrary, the corollary was for the benefit of the protected peoples, even at the expense of Americans at home.

What appeared to some—especially in London and Paris—like saber rattling actually was a doctrine rooted in TR’s core beliefs: that peace was not the natural order of things, that Americans were not insulated against social upheavals and power politics in the rest of the world, that “spheres of interest” were not threats to peace but were rather an inevitable part of world order. Hence, great powers must police the world, assuming, of course, that they were doing so for moral purposes. These views were based on a concept of global—including military—strategy in turn founded on age-old balance-of-power theories. Roosevelt had adopted these theories during the 1890s. A century later Henry Kissinger, no neophyte in this area, would judge that TR “approached the global balance of power with a sophistication matched by no other American president and approached only by Richard Nixon.”

...

Bashing meddling nations abroad and arrogant capitalists at home would be TR’s election strategy in 1904. For the Democrats, 1904 was the year to “stop Roosevelt.” Still switching back and forth between conservative Clevelandism and progressive Bryanism, the Democrats nominated conservative judge Alton B. Parker for president. His campaign was as colorless and cautious as TR’s was dramatic and strident. Carrying every state in the North, Roosevelt won 7.6 million popular and 336 electoral votes to Parker’s 5.1 million and 140 electoral votes, with socialist candidate Eugene Debs garnering 400,000 votes. Parker had not won a single state outside the South. As for Roosevelt, now he could say that he was no longer a political accident. The New York Sun called it the most “illustrious personal triumph in all political history.”

In his euphoria on election night, the president revealed the qualms he had about holding personal power and his need to reject power, even as he clung to it, through some kind of Washingtonian abnegation. Evoking the two-term tradition, he said, “Under no circumstances will I be a candidate for or accept another term.” Even so, TR was not prematurely opting out of the power game. After receiving the news of his victory, he was also reported to have said, “Tomorrow I shall come into my office in my own right. Then watch out for me.” Would his rejection of office haunt his future wielding of power?

Few rejoiced more in Theodore Roosevelt’s 1904 victory than twenty-two-year-old Franklin Roosevelt. FDR so adored and esteemed his distant cousin that four years earlier he—nominally a Democrat—had joined the Republican party in order to campaign for the McKinley-Roosevelt ticket. He wrote home then: “Last night there was a grand torchlight Republican Parade of Harvard and the Mass. Inst. of Technology. We wore red caps & gowns and marched by classes into Boston & thro’ all the principal streets.” Four years later, in 1904, he cast his first vote in a presidential election—of course for Cousin Theodore. “My father and grandfather were Democrats and I was born and brought up as a Democrat,” Franklin later said, explaining that, in 1904, “I voted for the Republican candidate, Theodore Roosevelt, because I thought he was a better Democrat than the Democratic candidate.”

Later that November of 1904 the engagement of Franklin Delano Roosevelt to marry Anna Eleanor Roosevelt, his fifth cousin, was formally announced. “We think the lover and the sweetheart are worthy of one another,” a pleased Uncle Ted wrote to his niece. “Dear girl, I rejoice deeply in your happiness.” The couple attended TR’s inauguration the following March 4, lunched at the White House, and danced together at the Inaugural Ball.

Their wedding took place two weeks later in New York, on March 17, 1905—Saint Patrick’s Day. “Only some utterly unforeseen public need will keep me away,” the president had written to Eleanor. On the morning of the wedding, leading his Rough Riders, President Roosevelt exuberantly marched in the massive parade, 30,000 strong, as it surged up Fifth Avenue, surrounded by throngs of office workers, storekeepers, shopgirls, and cheering onlookers. Uptown, Roosevelt left the parade and its working-class commotion, making his way to the brownstone of Eleanor’s aunt, Mrs. E. Livingston Ludlow, on East 76th Street, where the elegant wedding guests of the social elite—Livingstons, Ludlows, Jays, Astors, and the grande dame Mrs. Frederick Vanderbilt—were already assembled.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt stood in a small foyer, chatting about schooldays with his former headmaster, the Reverend Endicott Peabody, and his friend and best man Lathrop Brown. The bride, in her grandmother’s lace and her mother-in-law’s pearls, attended by her bridesmaids, nervously waited upstairs.

Shamrocks in his buttonhole, top hat in hand, President Roosevelt dashed in. The wedding could begin.

Concerned about Eleanor’s welfare ever since the death of her father, his brother Elliott, ten years before, TR was mightily pleased to give the bride away. Taking his niece by the arm, the beaming uncle escorted her down the circular staircase. “Who giveth this woman in marriage?” the Rev. Mr. Peabody asked. “I do!” the president announced loudly, so as to be heard above the voices of the Ancient Order of Hibernians singing “The Wearing of the Green” in the street.

“Well, Franklin,” the president barked at the end of the ceremony, “there’s nothing like keeping the name in the family!” and promptly went off in search of refreshments. The guests followed, irresistibly drawn to his aura of energy and high spirits. Franklin and Eleanor trailed after everyone else into the library and together cut the wedding cake while Uncle Ted regaled the group with his stories.

The president and his wife then traveled downtown, escorted by the 69th Regiment, to the famous Delmonico’s restaurant, where TR was the featured speaker at the annual dinner of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick. Franklin and Eleanor left for their honeymoon, first in Hyde Park and then in Europe. Not only had Franklin “kept the name in the family” by marrying the president’s niece, he had entered the ebullient Oyster Bay side of the family.

The startling similarities between Theodore’s and Franklin’s careers were no coincidence. Sons of socially established New York families, both attended Harvard, studied law and were bored by it, entered politics in their twenties, served in the New York State legislature, won appointments as assistant secretary of the navy, married well, fathered six children (one of FDR’s and Eleanor’s died), served as governor of New York, and ran for vice president of the United States. That the two patterns are identical is perhaps less extraordinary than one might think, for Franklin deeply admired TR and fervently wished to emulate him. And perhaps Theodore to a degree was encouraged by the support of young people like Franklin and wished to inspire and lead them.

The early years of the two men, on the other hand, were quite dissimilar. Theodore grew up among loving siblings; Franklin was an only child. He played with a niece and nephew who were actually older than he—Helen and James (“Taddy”) Roosevelt, children of Franklin’s half brother, “Rosy”—as well as with boys from neighboring estates along the Hudson. But mostly he was alone or in the company of adults. Thrown on his own resources, he started a lifelong interest and expertise in trees, birds, crops, boats, and, perhaps to a lesser extent, books.

Still, young Franklin was brought up, as one governess, said, “in a beautiful frame.” On the Roosevelt side, he, like Theodore, descended from Claes Martensen Van Rosenvelt, who sailed to New Amsterdam from Holland in the 1640s. His mother’s family, the Delanos, besides liking to trace their origins back to William the Conqueror, were proud to claim Philippe De La Noye, who arrived in Plymouth in 1621, as their ancestor.

The Roosevelts lived gracious lives on their secure Hudson estate. When they traveled—to Fairhaven, Massachusetts; to Campobello Island, in Canada, opposite Eastport, Maine; or to England and the Continent—they may have seen new places but they always surrounded themselves with the same kind of people. When they went by rail, they traveled in a private car. And aboard ship, as Franklin’s mother, Sara, said, there were always “people one knows.” Although Paris and London were familiar places, much of the world was invisible to them—the world of immigrants and grimy New York tenements, the world of strikers and farmers, the world of the squabbling Irish politicians in nearby Poughkeepsie. The Delanos, it was said, “carried their way of life around them like a transparent but impenetrable envelope wherever they went.”

They particularly frowned upon the “new” millionaires—like the Vanderbilts—who had built pretentious, mausoleumlike palaces along the Hudson, so unlike the comfortable and relatively simple estates of the old aristocratic families who never “showed off.” One day in 1890, Franklin’s mother announced at breakfast that Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt had invited the Roosevelts to dinner. “Sally, we cannot accept,” pronounced FDR’s father. “But she’s a lovely woman, and I thought you liked Mr. Vanderbilt too,” objected Franklin’s mother. His father conceded that he served on boards with Mr. Vanderbilt and liked him. “But,” he added, “if we accept we shall have to have them at our house.”

In the manner of the English upper-class families they knew, Sara and James Roosevelt sent their son off to private school when he turned fourteen. The school was Groton, which had already achieved standing among the social elite because of the leadership of its rector, Endicott Peabody, also a member of the elite. Here Franklin was not listened to, as he had been at home. Most of his classmates had arrived one or two years earlier than the fourteen-year-old from Hyde Park, and they “had already formed their friendships,” he later told Eleanor; he had remained “always a little the outsider.” The older boys, in typical prep school fashion, hazed him; his classmates were put off a bit by his slightly English accent, the perfect punctuality he achieved in order to win a school prize, his courtly deference to Rector Peabody. He conformed both to Peabody’s rules and to peer pressure to survive, meanwhile writing letters home that chirped about his small successes and occasional failures, which he explained away with minor rationalizations and a fib or two.

He already displayed a desire to excel, an ambition to gain recognition and praise—an ambition probably fueled all the more by his failure to be more than a grade-C athlete and a grade-B scholar. Yet it was not Grotonian to expose this ambition to Peabody or the school, and he dared not share his feelings with his doting mother and his ailing father. Those feelings spilled over, though, when Peabody did not include him among the senior prefects he chose, while including the headmaster’s own nephew.

“Everyone is wild at the Rector for his favoritism to his nephew,” Franklin wrote home, “but the honor is no longer an honor & makes no difference to one’s standing.” But he seethed for weeks afterward.

Deepening the pain was his own ambivalence. He loved the school but had been thwarted by it; he liked many of his schoolmates but felt merely liked in return and not well liked; he both revered the Rector as something of a father substitute and feared him as well. He was caught between an ambition to achieve and a longing to be one of the boys. These ambivalences intensified at Harvard, which Franklin entered in the fall of 1900.

...

Anyone walking into Franklin’s suite in Westmorly Court on Harvard’s Gold Coast would have thought he had nothing but the happiest memories of Groton. School pennants festooned the walls; team photographs and school mementos lined the marble mantels. He and his roommate Lathrop Brown breakfasted, lunched, and dined with other Grotonians, and in the evening, becoming less exclusive, they congregated at Sanford’s famed billiard parlor with Saint Paul’s and Saint Mark’s fellows.

Freed of Peabody’s stern discipline, Franklin became a man about town, dropping in on Boston society parties, socializing with other private-school graduates in various Harvard clubs, and spending plenty of time cheering Harvard teams. He seemed destined to divide his life between being an amiable clubman and a Hyde Park squire and gentleman.

Yet within this apparently frivolous socialite there burned an ambition to be something much more. This ambition was first centered on The Crimson, Harvard’s student newspaper. He missed selection for the initial freshman roster, tried again, won a post as editor, worked his way farther up the ladder, won the position of managing editor over a rival, and automatically succeeded to the editorship, grandly called “President,” of The Crimson. The twenty-two-year old editor was hardly a crusader, though, except for wider boardwalks in the Yard, better fire protection in the dormitories, and more freshman enthusiasm for their football team.

His ambition burned for something still more prestigious than editing The Crimson. He was desperately eager to become a member of Por-cellian. Sons customarily followed their fathers into this organization. Franklin’s own father had been an honorary member, without making too much of it; far more important, Theodore Roosevelt had been a member and he did make much of it. It was a Roosevelt family tradition. But Franklin was rejected—literally blackballed by one or more of sixteen students who secretly deposited a black ball into a wooden ballot box that was passed around the table.

He was astonished, mortified, and angry, for he had considered acceptance into Porcellian the “highest honor.” Many years later he said that his rejection had been the “greatest disappointment” of his life; Eleanor Roosevelt thought it gave him an inferiority complex, though perhaps it also helped him sympathize with life’s outcasts. But disappointment merely goaded Franklin to more effort. In his senior year he ran for a single prized position, class marshal, and lost again. Once more deeply mortified but undaunted, he tried again, for head of the 1904 class committee. This time he won—by 168 out of 253 votes. Thus he learned a lesson from this, his first electoral victory: Sheer persistence paid off, even in the rarefied politics of Harvard.

What else did Franklin learn at Harvard? He was lucky to have a wide choice of courses as a result of President Charles W. Eliot’s having broadened the curriculum and pioneered a freer choice of electives. After taking such required basic courses as English literature and European history in his freshman year, Franklin chose recent American history, English parliamentary history, and economics among other courses in his second year, and a somewhat similar set in his third, along with a scattering of “liberal arts” electives such as paleontology, public speaking, fine arts, and philosophy. His general grade average in these years was a gentleman’s C+.

Grades aside, his educational experience was mixed at best. He had as teachers some of Harvard’s “greats”: Shakespearean scholar George Lyman Kittredge, political scientist and later Harvard president A. Lawrence Lowell, American historian Edward Channing, speech and drama teacher George Pierce Baker, and Frederick Jackson Turner, who taught Development of the West. How faithfully he attended such courses varied widely, depending on how “practical” he found them and on other pressures of time.

The problem was not the teachers or the courses, tedious though some of them were, but how slowly Franklin’s mind was maturing. Despite later suppositions that Turner, who had written a famous essay on the influence of the Western frontier on American history, might have influenced FDR’s later political views, he in fact missed half of Turner’s course because he was on a Caribbean cruise. He complained later to a roommate that his courses had been “like an electric lamp that hasn’t any wire. You need the lamp for light, but it’s useless if you can’t switch it on.”

It was Franklin’s job to switch it on, but his mind, according to historian Kenneth Davis, seemed to “have remained at eighteen and twenty-two essentially what it had been at age fourteen”—“a collector’s mind almost exclusively, quick to grasp and classify bits and pieces of information, but unresponsive to the challenge of the abstract.” He dropped a course given by the great philosopher Josiah Royce after three weeks; if his views were affected by even more eminent Harvard philosophers such as William James and George Santayana, there is no record in FDR’s letters or anywhere else.

FDR’s most striking quality during this stage of his life was his seeming ability to ingratiate himself with almost everyone he met. He “got along” not only with his student friends in several clubs but with many of his teachers, not only with his Crimson workers but with the two Scottish printers who had to cope with late copy, not only with Boston matrons but with old Groton friends at Sanford’s. Above all, he got along with the most central and formidable person in his life—his mother.

He could not escape her. She dominated his life at Hyde Park, rented accommodations to be near him in Boston during many of his months at Harvard, managed his social life as far as she could. Franklin’s father died in 1900, during his freshman year at Harvard, and that loss had more tightly bound mother and son. Franklin rarely faltered in his expressions of devotion and almost invariably let her have her way when differences loomed, reluctant to repeat that open rebellion at Groton when he wished to visit Oyster Bay.

“Dearest Mama,” he wrote home from Harvard, “last week I dined at the Quincy’s, the Armory’s & the Thayer’s, three as high-life places as are to be found in blue-blooded, blue stockinged, bean eating Boston!,” admitting that it is “dreadfully hard to be a student a society whirler a ‘prominent & democratic fellow’ & a fiance all at the same time.”

It was this sociable, extroverted, accommodating facade of Franklin that most struck those who knew him. He always seemed smooth, too smooth. An admirer at The Crimson noted his “geniality,” “a kind of fric-tionless command.” Others found him superficial, lacking in conviction, overeager to please. Young women of his caste in particular found him smug, shallow, trivial, and always self-assured; at best Franklin Delano was, they joked, a “feather duster,” at worst a prig.

Perhaps those who called this young man superficial, however, shared some of that quality themselves. For there was another, less obvious side to Franklin. If he tended to cater to persons he met, it was his way of accumulating a wide range of information, especially in his travels abroad. If he was more a book collector than a book reader, at least it was books he was collecting rather than big-game trophies or some of the other fashionable acquisitions of the time. And if he wrote a paper at Harvard (with research help from his mother) about “The Roosevelt Family in New Amsterdam Before the Revolution,” he portrayed not only a great Dutch family in all its luster but one, he insisted, that had a “very democratic spirit” and that did “its duty by the community.” Indeed, if most of the old Dutch families had nothing to boast about but their superannuated names, it was because “they lack progressiveness and a true democratic spirit.”

To what extent Franklin deliberately modeled his Harvard career after Cousin Theodore’s we do not know; but he did appear to follow almost literally in TR’s steps. Inevitably Theodore remained far more Franklin’s political hero than intellectual model; the younger man could not begin to compete in the world of scholarship and ideas with his cousin, who authored dozens of historical books and articles and would even become the president of the American Historical Association. When Franklin graduated with the class of ‘04—he had remained an extra year, purportedly to work on a master’s degree but actually to continue editing the Crimson —he found the commencement anticlimactic. The real excitement was thirty miles north, where Cousin Theodore was Groton’s Prize Day orator. Franklin hurried up to his old school. He heard familiar words. “Much has been given you,” President Roosevelt told the boys, “therefore we have the right to expect much from you.”

...

One Roosevelt who did not find Franklin superficial was his fifth cousin Eleanor. They had known each other since childhood, when Franklin as a little boy had let baby Eleanor ride on his back during a family visit. But it was only when Eleanor returned to New York from her English finishing school and they met in the Madison Square Garden box of Franklin’s half brother, James “Rosy” Roosevelt, in November 1902 that their friendship quickly blossomed.

Although they inhabited the same stratum of high society, Eleanor and Franklin could not have had more contrasting upbringings. While Franklin had been the center of his parents’ world, doted on by nurses, governesses, and tutors, Eleanor had been a gangly, self-conscious child who had lost both her parents by the age of nine. Her patrician mother, Anna Hall Roosevelt, circulated in the upper reaches of high society. Judging Mrs. Astor’s Patriarchs’ Balls insufficiently exclusive, she helped start a more closed series of dances at Sherry’s restaurant.

Lovely and sociable as she was, Anna had maintained a distance from Eleanor, emotionally disowning her only daughter for her plainness. “You have no looks,” she informed the little girl, “so see to it that you have manners.” Taken to Europe by her parents, she was planted at one point in a convent that she hated, “to have me out of the way,” she later noted. Affectionate toward her two sons, Anna was cold and critical toward Eleanor, nicknaming her “Granny” and telling visitors, “She is such a funny child, so old-fashioned.” “I was always disgracing my mother,” Eleanor recalled painfully. But Anna was suffering herself, in a profoundly troubled marriage.

Eleanor’s father, Elliott, warm and expressive, clearly adored his daughter. Yet he was as volatile as he was exuberant, and Eleanor often feared she disappointed him by her timidity and her sensible and serious nature. But his problems ran far deeper; he was alcoholic, addicted to morphine, suicidal, violent, lurching from mistress to mistress, even sued by a servant for paternity. Theodore, convinced that his brother Elliott was “a maniac, morally no less than mentally,” insisted that he enter a mental institution for treatment. The family’s desperation became a public scandal when the New York Herald announced, ELLIOTT ROOSEVELT DEMENTED BY EXCESSES. WRECKED BY LIQUOR AND FOLLY, HE IS NOW CONFINED IN AN ASYLUM FOR THE INSANE NEAR PARIS.

Eleanor would later write that, as a child, she “acquired a strange and garbled idea of the troubles which were going on around me. Something was wrong with my father, and from my point of view nothing could be wrong with him.” While her father languished in an asylum in France, Eleanor lived with her mother and brothers in New York. Her mother suffered from severe migraines, and little Eleanor sensed that she could be of some use. Gently massaging her mother’s head, reveling in this newfound intimacy, Eleanor was thrilled just to watch her self-absorbed mother dress to go out in the evenings. “I was grateful to be allowed to touch her dress or her jewels.” Still, her happiest moments were spent alone, at her Aunt Bye’s house, in the maid’s sewing room. “No one bothered me,” she sighed in relief.

Elliott returned to the United States in 1892, but his wife, depleted by the ordeal of the marriage, refused to see him. That December, she died of diphtheria, and eight-year-old Eleanor was taken in by her maternal grandmother, Mrs. Mary Ludlow Hall. Little Eleanor moved into the stately brownstone on West 37th Street, peopled by a staff of servants as well as by her grandmother, her aunts and uncles, and their friends.

Whatever sense of loss Eleanor might have felt upon her mother’s death was wiped out, she confessed, by one fact: “My father was back and I would see him very soon.” Living for her father’s letters and infrequent visits, Eleanor was shuttled, with her brother Hall, back and forth between the Hall family’s Manhattan house and their estate along the Hudson River in Tivoli, New York. Time spent with her cherished father could be as traumatic as it was rare. One day, Elliott took Eleanor for a walk with his three terriers. Passing by the Knickerbocker Club, he stopped in for a drink, instucting Eleanor to wait outside with the dogs. When he emerged staggering, six hours later, Eleanor was still standing at the door. The doorman sent her home in a cab. Occasionally she glimpsed another world when she accompanied her father to serve Thanksgiving dinner at one of the newsboys’ clubhouses or when she helped her uncle decorate a Christmas tree for children in Hell’s Kitchen.

Her father’s condition deteriorated after the death of his wife in 1892 and the death of his four-year-old son, Elliott, in May 1893. After a period of drunken, violent upheaval, he died in August 1894. Eleanor, not yet ten, was not permitted to attend her father’s funeral. A few years after his death, Eleanor wrote in a school essay that her father was “the only person in the world she loved.” Years later, in 1933, she would edit and publish her beloved father’s letters, Hunting Big Game in the Eighties.

Bereaved, lonely, and painfully shy, Eleanor found solace in books, music, nature, and a rich fantasy world. Little by little, she came to feel at home on 37th Street and at Tivoli. She would later remember happy evenings when family members played with her and her brother, but she would also recall that her grandmother said no to her requests so often that she stopped asking her if she might do anything outside the daily routine. Grandmother Hall spent most of her time in her bedroom, and her four children, daughters Pussie and Maude and sons Vallie and Eddie, lived their mostly self-absorbed, increasingly erratic, upper-crust lives, her uncles principally engaged in drinking, gambling, and socializing with the high-living Diamond Jim Brady, her aunts engaged in “elegant leisure.” Still, Pussie and Maude were Eleanor’s “early loves.”

While her aunts and uncles, Eleanor later admitted, could scarcely have been said to have contributed to “the greater social organization we call civilization,” she did nevertheless feel that the elite milieu taught her “self-discipline.” “Social life was very important in my grandmother’s world,” Eleanor would later write, “and her social code demanded a great deal of self-discipline—particularly of women. Social obligations were sacred—no matter how you felt, the show must go on.” Eleanor would credit this stern code of behavior for getting her through myriad difficult occasions later in life. Her upbringing also provided her with a powerful conscience and sense of duty. Her grandmother made it clear that the “well-born” had obligations to those less well endowed. “I remember how, as a girl of five, I was taken to wait on the tables at the Thanksgiving dinner for the Newsboys’ Club,” she wrote. “My grandmother made me go to the Baby’s Hospital [sic] one afternoon a week to play with the sick.” As a young girl, Eleanor’s “chief objective” was to do her duty, she admitted, adding, “not my duty as I saw it, but my duty as laid down for me by other people.”

Once a year Eleanor was invited to her aunt and uncle’s home in Oyster Bay. “Eleanor, my darling Eleanor,” the ebullient TR would joyfully greet her, hugging her so tightly that, his wife Edith remarked, “he tore all the gathers out of Eleanor’s frock and both buttonholes out of her petticoat.” For Eleanor, visits to Sagamore Hill were “a great joy”; they swam, picnicked, camped, chased through haystacks in the barn, and climbed up to the gun room on the top floor where Uncle Ted would read poetry aloud. But neither the Hall family, wary of the boisterous Roosevelts, nor the Theodore Roosevelt family, fearful that Eleanor had inherited her father’s “genes” and would be a bad influence on daughter Alice, who was Eleanor’s age, were truly eager to mingle, and visits to Oyster Bay were rare.

Mrs. Hall’s decision to send Eleanor to England in 1899 to attend Marie Souvestre’s Allenswood School transformed the fifteen-year-old girl’s life. As a child, education and learning had been far less important than the “social graces which made you attractive and charming in Society,” Eleanor recalled. Now, at Allenswood, a school chosen for her by one of TR’s sisters, her world would widen.

The young girl found a glowing inspiration and mentor in Mile. Souvestre, a woman she considered “intellectually emancipated.” Eleanor flourished under her care. Intellect, sensitivity, kindness, and nobility of soul: these were cherished at Allenswood. Because Mile. Souvestre loved and esteemed Eleanor, more and more the other girls did too.

Like TR in the West, Eleanor was reborn at Allenswood. “I felt I was starting a new life,” she later wrote. Eleanor studied French, Italian, English, German, Latin, history, and music. The Halls, Eleanor realized, had taken “very little interest in public affairs,” but at Allenswood, Eleanor soon began to engage with the world, in heated discussions of politics, social issues, and art. She learned to speak French fluently, made close friends among students and teachers alike, and traveled throughout Europe with Mile. Souvestre, gaining a new self-assurance. “Though I lost some of my self-confidence and ability to look after myself in the early days of my marriage,” she later commented, “when it was needed again, later on, it came back to me more easily because of these trips with Mile. Souvestre.”

In the late spring of 1902, Eleanor left Allenswood for good: at eighteen, it was time, her grandmother insisted, for a young woman to “come out” in society, and “not to ‘come out’ was unthinkable.” Eleanor was heart-broken to leave her studies and her dear teacher, who warned her not to get “carried away in a whirl of exciting social activities,” urging her to defend herself against all the “temptations” of the frivolous upper-caste life. As long as she lived, Eleanor would cherish those letters, always keeping Marie Souvestre’s portrait on her desk.

She returned to New York a poised, accomplished, and self-assured young woman. Her debut, for which she wore a becoming Paris gown, subjected her to “utter agony.” She found the social whirl of the city—dances, cotillions, theater parties—intimidating and irrelevant, but it nevertheless sucked her in. “Haunted” by her upper-class upbringing, she admitted believing that “what was known as New York Society was really important.”

Yet, that winter, with like-minded friends in the Junior League—“just a group of girls anxious to do something helpful in the city in which we lived”—she found stimulating volunteer work teaching children on the Lower East Side and investigating sweatshops and women’s working conditions for the Consumers’ League. Taking the elevated railroad downtown, she walked across the Bowery to the Rivington Street Settlement House, along streets she described as “filled with foreign-looking people, crowded and dirty.” Though the “foreign-looking people” and filthy streets filled her with “terror,” she learned not to fear contact with poverty. One day, one of her little pupils invited her to come home with her. “Needless to say,” she remarked, “I did not go.” Eleanor, after all, was still a debutante, the niece of the president of the United States.

Occasionally Franklin would come down to the settlement to escort Eleanor home. Was he her “feller”? the little girls asked, but Eleanor did not know what the word meant. One day, Franklin arrived at Rivington Street only to find that one of the little girls was ill and needed to be taken home. He and Eleanor carried the child through the noisy streets and up the grimy, smelly, unlit stairs to her parents’ tenement apartment. “My God,” an astonished Franklin blurted out after the experience, “I didn’t know anyone lived like that.”

In New York City high society, she later observed, “you were kind to the poor, you did not neglect your philanthropic duties.” One accepted invitations to dine and to dance “with the right people only” and arranged one’s life to live in their midst. “In short, you conformed to the conventional pattern.” Oddly, that conventional pattern, of charitable works and settlement houses, enabled some of the ladies of Eleanor’s social class not only to become social activists but even—as in the cases of Eleanor, Frances Perkins, and others—to enter the political arena.

The friendship between Franklin and Eleanor might have surprised some of their friends. The two seemed like polar opposites: he, the urbane, self-assured, handsome Harvard student and man about town; she, the shy, serious, plain young woman. Yet amid their differences each recognized an important complementary quality in the other. Franklin could make her feel lighthearted—something she had hardly known since her father’s death. His presence was like a fresh current stirring the depths of her loneliness. She in turn aroused his deeper, more thoughtful self.

“Eleanor has a very good mind,” he told his mother. They talked for hours, read poetry aloud, spent New Year’s at the White House together. “Sat near Eleanor,” Franklin penned in his diary. “Very interesting day.”

Her name appeared with increasing frequency in his diary and letters, and finally he proposed during a visit to see her younger brother Hall at Groton. The following week the couple apprehensively told Franklin’s mother of their plans. Sara, her own intimacy with her son threatened, persuaded them to wait a year before announcing their engagement, in order to make sure they had made the right decision. They reluctantly agreed.

During the following year, between Thanksgiving of 1903 and that of 1904, the couple was supposed to observe the strictest propriety. Until their engagement was announced, they were to go nowhere unattended by a chaperone. Trailed by a maid, Eleanor would travel to Cambridge for football weekends; in New York their time would be spent attending plays, luncheons, church, and other public affairs. Yet they found ways of slipping away. And Franklin increasingly came to see Eleanor in New York instead of his mother in Hyde Park.

Eleanor’s biggest worry was the gracious but imperious mother. Franklin, after all, was the sun around whom Sara’s world revolved. Eleanor learned to show remarkable tact and sensitivity toward her mother-in-law. Always highly attuned to people in need, she knew what it was to feel abandoned; she diligently strove to include Sara. After all, she herself wanted, if not a mother, then stability and security.

When the couple finally announced their engagement just after Thanksgiving, 1904, excited congratulatory messages streamed in from friends and family, among them a letter to each from Eleanor’s Uncle Theodore.

“No other success in life,” he wrote Franklin, “not the Presidency, or anything else—begins to compare with the joy and happiness that come in and from the love of the true man and the true woman, the love which never sinks lover and sweethearts in man and wife. You and Eleanor are true and brave, and I believe you love each other unselfishly; and golden years open before you. May all good fortune attend you both, ever.”