Herblock, 1942. (Courtesy FDR Library)

On the eve of 1943, the Roosevelts held their usual New Year’s Eve party at the White House for family and close friends. As the midnight hour struck, the president raised his glass of champagne and offered his usual toast to the United States, but this year he added, “and to United Nations victory.” Earlier that evening the guests had watched a film about Nazi villainy in North Africa, Vichy collaborators, and three escapees from occupied France starring Ingrid Bergman, Humphrey Bogart, and Paul Henreid. The film was Casablanca.

Was FDR, always a great tease, sending a cryptic message to his intimates? Nine days later Roosevelt and Hopkins and their party traveled by train to Miami, destination Morocco. The trip had all the makings of a Hollywood propaganda film—except it was probably the most decisive meeting that the president would ever attend.

FDR treated the journey as a first-class holiday, Hopkins noted, telling his favorite old yarns and not losing his composure when one of the sailors carrying him slipped and the commander in chief landed on his rear. The two men laughed about the “unbelievable trip” even beginning. It would be the first time this president—or any president—traveled by air. Roosevelt went to see for himself, to speak for himself—above all, Hopkins reflected, he just wanted to make the trip. He seemed to Hopkins as excited as a sixteen-year-old as the Pan American clipper taxied out of the harbor on the first leg to Africa. The president, hunched over by a window, missed nothing as the plane flew over the Citadel in Haiti and the one-hundred-mile-wide Amazon River mouth. After hops to Natal, then eighteen hours to Gambia and a night on the cruiser Memphis at this old slave post, he flew on over mountains and desert to Casablanca.

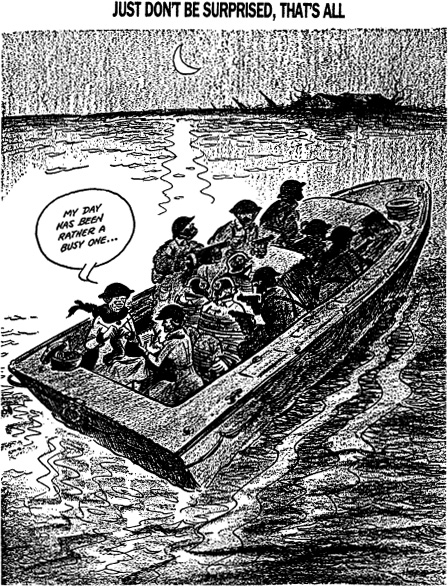

Agreeably settled in a commodious villa, the president soon was presiding over a wartime conference that seemed at times more like a combination reunion and old home week. FDR greeted his close comrade-in-arms Churchill, the combined British and American chiefs of staff who had been meeting for three days—and Lieutenant Colonel Elliott Roosevelt, in from his air force reconnaissance unit; Lieutenant Franklin D. Roosevelt Jr., summoned from an Atlantic Fleet destroyer; and Hopkins’s son Robert, ordered in from a Tunisian foxhole.

All the hail-fellow-well-met camaraderie under Casablanca’s sunny skies could not camouflage irksome divisions in the Allied camp. The problem was not only the “natural contrariety of allies,” as Churchill called it, but the inevitable rivalries of services and ambitions over strategies and tactics, within both the British and American camps. The Casablanca conferees did not differ over the vital importance of the big jobs ahead: winning the shipping battle of the Atlantic, mounting an invasion of Europe from the west, massively helping Russia, pushing on up from the Mediterranean, meantime sustaining joint operations with China and pressing the sea-air-ground effort in the Pacific. The problem lay in priorities, the very essence of strategy.

While Roosevelt’s generals and admirals still felt torn between European and Asian needs, they agreed under General George Marshall’s leadership on the top priority: a massive cross-channel attack through France in 1943. Fresh from their successes in North Africa, and with half a million troops at their disposal, the British looked eagerly toward Sicily and points north and east. While some of the Americans wanted to get on with the fight immediately in the Mediterranean, most of Roosevelt’s planners—especially Marshall—feared that Italy would be a sideshow draining troops from the cross-channel buildup.

Whatever worries the other chiefs might have had about such drainage, Churchill did not share. Rather, he saw Italy as a superb opportunity both to attack the allegedly “soft underbelly” of the Axis in the Mediterranean and to use southern Italy as a base for all sorts of opportunities. But Churchill’s first target was FDR. Before the conference he instructed his chiefs “not to hurry or try to force agreement, but to take plenty of time; there was to be full discussion and no impatience—the dripping of water on stone.”

Churchill knew his man. Attracted by all the tactical advantages of an Italian strategy, the opportunistic Roosevelt agreed to give the Mediterranean the immediate top priority. Despite British assurances that a successful Mediterranean strategy would make the cross-channel attack more assured of succeeding, it was also clear that an Italian campaign would delay the big attack from 1943 to at least 1944. This possibility—and the fact that other priorities like Asia were accordingly diminished—left Hopkins and the military depressed; Roosevelt seemed content to seize the tactical opportunities of the moment.

The stepped-up Mediterranean priority and the lowering of other alternatives raised some dire political problems that the two leaders would have to face during 1943. For Roosevelt, far more than Churchill, the key political issue was unconditional surrender. Whatever his vagaries on other political matters, FDR for months had been making clear that the Axis nations would be compelled to surrender without negotiations or conditions. Roosevelt would risk neither a repetition of the problems of the World War I negotiated peace nor disunity among Moscow, London, and Washington.

Churchill had wholly agreed with the doctrine in principle, but he was already wondering at Casablanca whether an exception might be made for Italy. Then the president sprung a surprise on the prime minister when he suddenly announced at a press conference that the “elimination of German, Japanese, and Italian war power means the unconditional surrender by Germany, Italy, and Japan.” That did not mean the destruction of their populations, FDR added, but rather of the “philosophies in those countries which are based on conquest and the subjugation of other people.”

Was the president’s sudden announcement a result of the thought “popping in his mind,” as he later contended, or, more likely, a calculated ploy to secure Churchill’s adherence publicly to applying the doctrine to Italy? The prime minister, who was taken by surprise only by FDR’s unilateral announcement, not by the doctrine, gamely backed up the president.

A more immediate political problem for the two men was a matter of prickly personality more than political strategy, and its name was Charles de Gaulle. De Gaulle and General Henri Giraud were still vying for leadership of the Free French. FDR had come to despise de Gaulle for his pretensions as the sole anti-Vichy leader, his stubbornness, and—not least —the liberal and radical support he had aroused back home as the heroic leader of the French Resistance.

Invited to Casablanca to meet and harmonize with Giraud, de Gaulle came grudgingly but they stalled for two days, while FDR notified Secretary Hull in Washington that he and Churchill had “delivered the bridegroom,” Giraud, but “our friends could not produce the bride, the temperamental lady de Gaulle,” who showed no intentions of “getting into bed” with his rival. Then FDR, like a wily marriage broker, brought the two together, maneuvered them into shaking hands for the camera, and helped patch up an agreement between the two generals for “permanent liaison.”

Another of FDR’s ventures with the French connection proved more fruitful. Despite a packed schedule at Casablanca, he hosted a banquet for the sultan of Morocco, a prime leader in Morocco’s struggle for independence from France. A longtime critic of French colonialism, the president took extraordinary pleasure in supporting that struggle and offering aid in Morocco’s economic development. The sultan, who would assume the throne as King Mohammed V, would never forget the president’s warmth and hospitality. Nor would his thirteen-year-old son, rushed out of his Rabat school that day to attend the banquet—and who later, as King Hassan II, would support the United States decade after decade, through the Cold War and North African turbulence.

Altogether, FDR’s Casablanca week, in January 1943, was one of the most enjoyable and fulfilling of his entire life. He was in the fullness of his vigor and virtuosity as he presided, mediated, bargained, stage-managed, manipulated, roared with laughter, and denounced with high indignation. The conference proclaimed some noble objectives, agreed on important short-term goals, and fine-tuned military operations.

But it was only a partial success, largely because of one man who did not join the happy few who were there. Stalin, though invited, declined because, he said, he had a war to fight.

Reeling from the casualties the Russians were suffering in stalling the Germans, Stalin had called for a second front in western Europe that would provide some relief from the German attack on Russia. He had sent his toughest negotiator, Foreign Commissar Vyacheslav Molotov, to Washington on May 29,1942, to present his second-front demands face-to-face. Molotov wanted a straight answer. What was the president’s position on a second front? It had to be 1942, the Russian insisted, not 1943, because by 1943 Hitler would be master of Europe and the task would be infinitely more arduous. Roosevelt and Churchill skillfully dangled the bait of a big invasion in order to keep the Russians in the war without making a final commitment about an attack in 1942, and without offering Moscow anything more than a series of half promises that in the end did not result in a flat promise—or in an invasion. The upshot: The Russians would continue to take horrendous losses while London and Washington would take their time. FDR even had to tell Molotov that lend-lease supplies to Russia would have to be reduced from 4.1 million to 2.5 million tons in the coming year. Pacific war needs were eating away at supplies.

And so, in January 1943, with no second front having been created in 1942, Stalin was in no mood to join his allies in Casablanca. But in Morocco, for the moment, Roosevelt and Churchill could bask in tasks well done, and bask they did. Churchill insisted on driving with Roosevelt to Marrakesh, where he said they could get an incomparable view of the Atlas Mountains. After climbing to the top of a tower, the prime minister urged the president to come up, and soon, his legs dangling, he was hoisted up on a chair composed of the arms of servants. So Casablanca ended, as it had started, with a Hollywood touch of comradeship and dramaturgy.

Command leadership tightened its grip on the people’s lives during 1942 and 1943. The commander in chief imposed curb after curb on people’s buying, spending, consuming, traveling. He shuffled and abolished war agencies under his war powers, occasionally refused to carry out congressional legislation he opposed, and despite the venerable separation of powers, enjoyed the counsel and cooperation of at least three of his appointees to the Supreme Court. War agencies penetrated ever more deeply into the daily lives of Americans. More millions of men, and some women, came under the male hierarchical discipline of the military. People groused, swore—and submitted.

For millions of Americans it was a time to make sacrifices for a high moral purpose. For millions of others, it was a time to carry on business as usual. Net income per farm doubled during the war years; the after-tax profits of corporations almost doubled. In a time of desperate need for production, producers were in the driver’s seat.

Millions of workers too were producers, but their experience was quite mixed. For years, FDR’s approach to labor had been personal, paternalistic, supportive, and manipulative. As the war production effort intensified he continued to be paternalistic and supportive, but now he had to depend more on institutions. Chief of these was the National War Labor Board, with tripartite representation but dominated by the four public members—particularly William H. Davis and Wayne Morse—who took on the heavy responsibilities of both holding down spiraling wage rates and settling strikes.

During 1942, as walkouts continued even after Pearl Harbor, the board had searched for a formula that would accommodate both the opposition of business to an enforced “closed shop” and labor’s demand that the bosses not use the war for union-busting drives. The board reshaped an old formula, maintenance of membership, under which members had had to stay in their unions for the life of the contract, into “maintenance of voluntarily established membership,” under which employees had ten or fifteen days to quit the union before membership was final. Thus did the board seek to reconcile liberty with order and equality.

Surprisingly, in the face of hostility to strikes on the part of the public and especially soldiers overseas, and despite a “no-strike” pledge by labor and extensive mediation and conciliation agencies, walkouts not only continued but escalated during the war years: from approximately 2,000 in 1942 to 3,700 in 1943, to nearly 5,000 in 1944. The president, bypassing some of his agencies, fought a long and bruising battle with Lewis, who was unpopular with the military and much of the public—“John Lewis, damn your coal-black soul!” cried the soldiers’ paper, Stars and Stripes—but had the absolute loyalty of the union men who mined the coal.

“FDR walked with consummate skill the tightrope between angry workers and an irate public,” judged historian William O’Neill. “In a no-win situation, he lost almost nothing,” ensuring a steady supply of coal while protecting the effort against soaring wages.

...

What about unorganized Americans: women, blacks, children, “aliens”?

Entering the 1930s with abysmally low wages—on the average half to two-thirds that of men—women had ended that decade in a scarcely improved position. The New Deal had indeed been less than half dealt for working women. NRA codes endorsed sex differentials 14 to 30 percent lower than for men. Most relief and work programs employed less than 10 percent women. CCC camps were set up for young men by the hundreds; despite Eleanor Roosevelt’s intervention, only eighty-six were set up for women. Women’s organizations such as the General Federation of Women’s Clubs and the Women’s Trade Union League had no clout, historian Irving Bernstein concluded, and could be safely ignored.

From 1940 to 1945 the number of women in the labor force shot up from less than 13 million to more than 19 million. With women flooding into war plants and services in tight labor markets it was expected that their wages would rise, but these still lagged behind men’s. Some unions resisted (and even struck against) women taking jobs that might leave veterans out in the cold when they returned from the front. There were many stories about “Rosie the Riveter” and other heroines of production, and defense work did give many women a heightened sense of self-esteem that lasted into their postwar lives. But somehow the glory rarely translated into higher wages and better working conditions.

When mothers suffered deprivations, so did many children. Schools were often congested, sometimes to double their capacity. Some schools were so crowded that many children did not even attend. Lack of child care and of extended families left youngsters to their own devices as parents worked graveyard shifts. Millions of children with working parents were left at home without adequate care. There were federal subsidies for child care under the Lanham Act and under Emergency Maternal and Infant Care programs, but they were rarely adequate. Eleanor Roosevelt appealed to the heads of industry to provide day-care facilities for workers’ children. A pioneering model was set up in one shipyard in Oregon, but there were no statewide or nationwide programs for toddlers. Some youngsters had neither schools nor home care nor day care. By mid-1943 almost 2 million girls and boys under eighteen worked on farms or in factories, usually at much lower pay than adults. Children were hardly a political pressure group.

Nor were African-Americans, outside of a few northern cities and a few “colored” unions. Even before Pearl Harbor, black leaders were finding once again that the white power structure could not be altered from the inside if you lacked both access to money and the right to vote; it had to be challenged from the outside. In April 1941 the National Negro Council had urged the president to abolish discrimination in all federal agencies by executive order. Meetings of Walter White and other black leaders, even with friends like union leader Sidney Hillman, who had joined the Office of Production Management, had brought little but promises. Then White, A. Philip Randolph, the revered head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and other black leaders threatened a march on Washington, to take place on July 1,1941, unless action was taken against discrimination in war plants.

Eleanor Roosevelt was the only real friend African-Americans had in the White House. Presidential aides Early and Mclntyre were Virginians with conventional southern attitudes. FDR himself viewed “Negro rights” with a mixture of personal compassion, social paternalism, recognition of pervasive racism in Congress, and a practical awareness both of blacks’ importance to the defense effort and their potential influence at the ballot booth. The general policy of the administration, to the extent it had one, was “separate but equal,” in the armed forces, in civilian agencies, and— at least by exhortation—in war industries, but the separation usually thwarted the equality. Now the black leadership was demanding that FDR live up to his 1940 campaign promises and make good on his words about “equal opportunity.”

Apprehensively Roosevelt watched the escalating plans for Randolph’s march on Washington. Typically, he tried to head it off not by open opposition but indirectly—in this instance through his wife, who had by now been backing black activists for years. “I feel very strongly that your group is making a very grave mistake,” Eleanor wrote to Randolph three weeks before the planned march. She feared that it would “set back the progress which is being made, in the Army at least, towards better opportunities and less segregation.” It might arouse even more “solid opposition” from “certain groups” in Congress.

It took iron resolve on the part of African-American leaders to stand up against their friends as well as their foes, but Randolph and his comrades were determined not to retreat without an executive order against discrimination. Calling Randolph and White to the Oval Office, FDR tried all his arts from persuasion to rhetoric. “What would happen if Irish and Jewish people were to march on Washington?” he asked, and answered the question himself—the rest of the American people would resent it.

But the president was beginning to weaken. He arranged a meeting of Eleanor, NYA head Aubrey Williams, and New York mayor Fiorello LaGuardia with black leaders in New York. After Randolph and White threatened a march on the New York City Hall as well, they negotiated an agreement that the president would sign. The march was called off.

It turned out to be both a symbolic and a hollow victory for African-American leaders. Symbolic, because at last blacks had a law—or at least an executive order—against discrimination, and an agency—at least a presidentially established one—to give the law some enforcement. Hollow, because the impact was very limited. The president set up a Commission on Fair Employment Practices within the defense bureaucracy but without any real policing power. He appointed a six-member board headed by Mark Ethridge, publisher of the Louisville Courier-Journal and a strong civil-rights advocate, and composed mainly of white members. Its staff consisted of a half dozen field investigators. But the main problem was the sheer intractability of the problem: a corporal’s guard was trying to breach the citadels of Jim Crow. Training and jobs were linked in a vicious circle: Employers turned away blacks because they had inadequate training; training classes were closed to blacks because of an alleged lack of jobs.

But some lessons had been learned. The president had learned that African-American leaders were deadly serious and would not cave in even to his persuasiveness and his power. Black leaders had learned that the “power system” could be breached only with militance and persistence. Southern leaders learned that a Democratic administration could, when the chips were down, turn against segregationist southerners. As for the segregationists, they revealed their fanaticism. Eugene (“Bull”) Connor, then and for years afterward head of Birmingham “Public Safety,” charged that the Fair Employment Practices Commission was causing disunity, that venereal disease was the number one Negro problem, and that the Ku Klux Klan would be revived.

“Don’t you think,” Connor demanded, “one war in the South” had been enough?

...

Across the nation, by 1943 the war was triggering an explosion of excitement, an outburst of volunteerism, and an outpouring of grass-roots participation without parallel in the American experience. This eruption rose far above class attitudes, racial tension, ethnic feelings, and interest-group self-protectiveness, as the American people responded as one nation to calls for a mass movement of activists. Towns held meetings, citizens formed committees, blocks elected captains, people sent off aluminum pots and pans to be made into airplanes.

Was the government not only triggering but fully unleashing the huge potential of people at home? Not in the eyes of many women. It was largely under their own initiative, rather than on government demand, that millions of women flocked into Red Cross centers, volunteered for the Women’s Ambulance and Defense Corps of America, served as security guards and couriers for the armed services, and organized their own groups. After Pearl Harbor a poll reported that 68 percent of the respondents favored a labor draft for women under thirty-five—almost three out of four women polled favored it—but Congress would not vote for something so radical.

Women, and many men as well, were simply moving beyond the government in their zeal to contribute. But for many women this was not enough; they wanted to serve in the armed forces. Only after Republican congress-woman Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts demanded that women be allowed to serve in the U.S. Army was the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps—soon to become known as the WAACs—set up to do clerical and other non-combatant work. Ten thousand women promptly volunteered.

The war experience of African-Americans was more mixed and complex. For hundreds of thousands of blacks the war meant migration—from south to north, from civilian to military life—that for some represented major turning points in their lives. But many faced the same problems of discrimination in the heavily segregated armed forces that they had encountered in civilian life. They did find educational opportunities in military service or with some defense programs that they had earlier been denied. Whatever fraternization they might have achieved with white military personnel overseas, however, quickly ended on returning home.

No sector of American life underwent greater change than education. “We ask that every schoolhouse,” the president said, “become a service center for the home front.” The schools took up the challenge with an array of efforts from bond drives to courses in Asian geography to paramilitary youth organizations. Some universities and schools came near to closing as male students and teachers were drafted and women left for factory and other war work. In 1943-44, liberal-arts graduates were fewer than half and law school graduates only one-fifth the prewar level. Science adviser Vannevar Bush estimated to FDR that science lost 150,000 college graduates and 17,000 advanced-degree graduates to the war.

As education was disrupted and protests streamed in from educators, Roosevelt sought a short-term solution. Stimson and Knox responded with the Army Specialized Education Program and the Navy V-12 program. By the end of 1943 the two programs had used idle college buildings at about 500 institutions to provide training for about 300,000 men. Students marched alongside ivy-covered buildings, uniformed officers took over classrooms, science professors worked on bomb technology and battle medicines in their laboratories. This augmented federal wedge in education would lay the groundwork for an ever greater federal role in the postwar years.

Heroic participation in the battle of the home front did not spring spontaneously out of the hearts and minds of civic patriots. It was mightily abetted by the most intensive, comprehensive, and sophisticated propaganda effort Washington had ever mounted. The main effort began with massive war bond campaigns. In charge of the effort, Treasury Secretary Morgenthau followed the shrewd insight “to use bonds to sell the war, rather than vice versa.” Hollywood stars, radio commentators, singers, famous bands, musicians—even violinist Yehudi Menuhin playing Mendelssohn’s Concerto in E Minor—were enlisted in the cause. As against the negative propaganda of World War I, much of the publicity produced or supervised by the Office of War Information under Elmer Davis struck the key themes of the global conflict, backed up by FDR’s unmatched skill at conveying war aims and peace goals to the public.

...

Perhaps never had the American people been so psychologically and emotionally aroused and fulfilled as they were during these war years. They had a heady sense of participation, of working with others, of taking on new tasks and accomplishing them, of pursuing a clear-cut goal—beat the Axis—as a first step to postwar peace and security. Paradoxically, never had the American people as a whole had their material needs so well satisfied. Despite rationing, tens of millions enjoyed higher wages, better clothing, more food, improved health care, and more job training than ever before; many had better housing and recreation, though under crowded conditions. These millions included huge armies of military men and women, who had considerable job security too, for a time.

One reason for this well-being was the continuation of the New Deal programs into the war—programs often enlarged rather than dropped. Eleanor Roosevelt was insistent that the social welfare measures for economic security and civil rights continue in some form. To her, this was what young people in particular were fighting for. When a public housing project for Negro defense workers in Detroit, the Sojourner Truth project, came under attack by white politicians, Eleanor intervened on the defense workers’ behalf and the Michigan national guard was called up, to assure black tenants the right to live in the housing project.

And Franklin Roosevelt, despite a public announcement of his shift from “Dr. New Deal” to “Dr. Win-the-War,” in fact continued in the former capacity as well. If it was necessary to bootleg New Deal measures to the American people under patriotic labels, this was wholly acceptable to him.

Never indeed had so many americans had it so good in so many ways. But these tens of millions did not include a million war casualties and the families who suffered over their deaths and wounds. And for the millions who were fighting in distant lands, the war was not just the “organized bore” that soldiers called it but an agonizing hell.

By 1943 the leaders of all the armies in Europe—American, British, German, Russian—were proclaiming that they were leading “people’s wars”: crusades for Freedom and Equality. Among those who were doing the actual fighting rather than talking, however, few were tasting either of these lofty aims. None had expected much freedom in their armed forces, of course, but the vast majority of fighting men and women experienced equality only in their common misery.

The grossest inequality lay between soldiers on the Soviet front and on the Anglo-American fronts: an inequality of death. Compared to the fierce Soviet defensive battles of 1942 and the huge offensives that lay ahead, American and British forces fought only limited battles in 1943, as they inched their way up the Italian boot past Naples. The postponement of the cross-channel invasion left the Soviet Union still with the brunt of the fighting. Hurling masses of troops and tanks against the enemy, the Russians suffered staggering losses that were beyond anything known in the history of warfare: 6 million military deaths from all causes, 10 million civilians killed, 25 million left homeless.

Within the American military as a whole there was an inequality of death; the chance of being killed on the average was less than one in fifty, but that chance radically escalated among rifle companies, armored battalions, combat engineers, medics, and tank destroyer units. It did not help to be an officer, except above the company-grade level.

Enlisted troops did not expect to share the creature comforts of officers—anyway, in combat areas everyone felt deprived—still, they did expect equality of recognition. But rewards for good conduct or great courage were grossly unequal. Combat air crews received more campaign stars than combat soldiers; headquarters personnel won more ground army medals than riflemen.

Servicewomen fared poorly compared to men. The original WAAC, which had been poorly trained and deployed, gave way in 1943 to a new Women’s Army Corps (WAC), placed directly under the general staff. Still, women were ridiculed as unsoldierly, slandered as promiscuous, caricatured as unfeminine, and employed in some of the most unfulfilling tasks—except by General MacArthur, who called them “my best soldiers.”

African-Americans predictably faced the old problem of segregation and discrimination, even in a new war for freedom and equality. The administration had planned to draft fewer blacks than whites, proportionately—and these mainly for service units. But manpower needs combined with black protests impelled the administration to boost blacks to the same level as whites in the army, a hike of around 10 percent. Inch by inch the army retreated from its discriminatory policies, appointing the first African-American general and promising to put some black combat units into the field. The main obstacle was not public opinion but rather foot-dragging within the services on the part of officers who vilified blacks as badly educated, unskilled, and undisciplined.

Why not then abolish all-black units and integrate? This aroused all the usual fears—of race riots in camps, of violence in southern military towns, even of black-white conflict during combat. The army sent some black combat units overseas, the little U.S. Coast Guard commissioned ten times more black officers than the navy, and as units became shuffled and reshuffled along the tortuous battlefronts, some de facto integration occurred.

Many lesbians and homosexuals faced the worst of circumstances. They had no equivalent to black and women’s organizations to fight for their rights on Capitol Hill. Some became combat medics or hospital personnel or chaplain’s aides; others were subject to witch hunts, thrown into “queer stockades” or brigs, sent home on “queer ships.” Only toward the end of the war did the army begin to alter its hard-line policy, as it ordered cases of discharged self-confessed homosexuals to be reviewed and their readmission to the army authorized.

And then there were those who lost their freedom for good. By the end of 1943 the American death toll was averaging around 5,000 a month; a year later it was rising to between 12,000 and 18,000 GIs each month. Of the 16 million Americans serving in all branches of the armed forces, losses totaled 1 million casualties, including 300,000 battle deaths and 100,000 other fatalities. But American losses paled next to the 6 million military deaths and 10 million civilian deaths suffered by the Soviets. In all lands tens of millions were left bereaved, widowed, orphaned, or coping with returning veterans who were physically or psychologically maimed by war.

...

Could anything justify such stupendous losses, such endless suffering and heartbreak? It would be “inconceivable—it would, indeed, be sacrilegious—if this Nation and the world did not attain,” Roosevelt declared in his State of the Union speech to Congress in January 1943, “some rea”, lasting good out of all these efforts and sufferings and bloodshed and death.” Victory in the war was the immediate task, but freedom from fear and want—enlarging people’s security throughout the world—would be the ultimate victory.

“After the first World War we tried to achieve a formula for permanent peace, based on a magnificent idealism,” the president continued, referring to the League of Nations. “We failed. But, by our failure, we have learned that we cannot maintain peace at this stage of human development by good intentions alone.” The Allies, “the mightest military coalition in all history,” must remain united to build world peace. “The people have now gathered their strength,” and nothing now could stop them.

Bold and timely in rhetoric but also scarred by Wilson’s—and his own—defeat in 1920 on the issue, the president during 1943 was caution itself in laying plans for a United Nations structure and organization. In 1942, he, Churchill, and Stalin had jointly composed a “Declaration of United Nations” which was signed by twenty-six nations, declaring that they would preserve human rights and justice in the world. Now, trying to gather support and avoid the debacle of the League of Nations, FDR had even allowed some Republicans to jump ahead of him; in April, Wendell Willkie had published One World, an instant best-selling account of his travels to Russia and China and a plea for United States cooperation to preserve postwar peace. GOP legislators were planning to draft their own statement on the issue. The president let Hull and a group of State Department experts move ahead—very quietly—on postwar peace planning. In Congress, J. William Fulbright and other Democrats were restive. The Arkansas senator asked FDR to support his resolution favoring international machinery with power adequate to maintain peace, but the president would not take the lead on this innocuous resolution.

Indeed, FDR’s ideas on UN organization were still evolving. Early in the war he had strongly favored UN domination by the Big Four—with Britain, China, Russia, and the United States as the “Four Policemen”—but State Department planners and many american liberals and internationalists favored one universal organization with effective representation of smaller nations. Already tough questions were rising, FDR knew—of the method of representing smaller nations, of a Big Four veto, of the nature of the world security force—questions that aroused for FDR disturbing echoes of the controversies that had helped kill the League of Nations.

In these hopes and fears the president had a partner in Eleanor Roosevelt. She too had lived through the euphoric and then lacerating days of 1919 and 1920, and she fully shared her husband’s central concern for a strong United Nations. She usually deferred to FDR on matters of political strategy—indeed, she asked him not to share any military secrets with her—but the first lady, in Joseph Lash’s words, “was haunted by the fear that the system of privilege and inequality within and among nations that had led to two world wars would inevitably breed more wars, despite a military victory, if the old division between haves and have-nots survived.”

FDR and Herbert Hoover at 1933 Inauguration.

(Courtesy Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library)

FDR, Warm Springs, December 1933. (Courtesy Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library)

FDR, Ruthie Bie, and Fala, February 1941.

(Courtesy Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library)

FDR and Winston S. Churchill, 1943.

(Courtesy Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library)

Eleanor during her trip to the South Pacific, 1943. (Courtesy Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library)

FDR and Eleanor at Val-Kill, 1943.

(Courtesy Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library)

FDR campaigning with Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, Jr., near Hyde Park, November 1944.

(Courtesy Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library)

FDR and Eleanor with their grandchildren at the White House, January 1945.

(Courtesy Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library)

Anna and Eleanor at FDR’s funeral, Hyde Park, 1945.

(Courtesy Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library)

Eleanor at the UN, 1947.

(Courtesy Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library)

Eleanor holding the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948.

(Courtesy Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library)

Eleanor and Adlai Stevenson, 1960.

(Courtesy Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library)

Eleanor with John F. Kennedy, 1961.

(Courtesy Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library)

(Courtesy Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library)

Eleanor Roosevelt’s funeral, Hyde Park, 1962. From left: Lady Bird Johnson, Jacqueline Kennedy, President John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Harry S. Truman, Bess Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower.

(Courtesy World Wide)

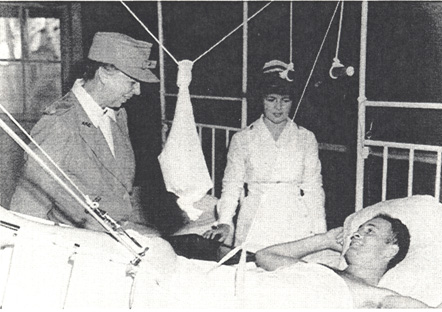

Eleanor’s concern for postwar peace, and her ideas about it, were strengthened and focused by her wartime travels. She had eagerly accepted Queen Elizabeth’s invitation to visit England in fall 1942. Normally the most courageous of women, she had felt her fears rising during the transatlantic plane trip, especially in regard to her strenuous itinerary and a stay in Buckingham Palace. But the king and queen met her at Paddington Station and made her feel comfortable in their palace, which she used as a base from which to tour bombed-out buildings in London, air-raid shelters, and army camps. She complained to General Dwight Eisenhower, then commander of U.S. forces in the European theater, when she discovered that the GIs were wearing cotton socks instead of wool. Code-named “Rover” by the American embassy because of her constant motion, she gave speeches about the war and received numerous members of deposed European monarchies—doubtless with the ardent acquiescence of her husband.

As she extended her travels, ultimately to the Pacific—New Caledonia, Samoa, Bora Bora, New Zealand, Australia, and Guadalcanal—and as she hosted VIPs in Washington such as Madame Chiang Kai-shek, Eleanor Roosevelt became more outspoken in her views about peace. Having challenged Churchill to his face on Britain’s 1930s policy toward Spain, she had no reluctance later in attacking his colonialism and his hope that he could return to the prewar world. The United States must join with “liberated people” around the world who were expressing the hopes for freedom and justice hidden in their hearts, she wrote in “My Day.” She wanted to extend the Four Freedoms, just as FDR did, but in her own way. People assumed—incorrectly—that when the first lady held press conferences, her remarks might forecast the president’s position on some issue. Still, she conveyed her views to him well enough through her reported speeches, evening talks with visitors they both hosted—and not infrequently by accosting him while he was still abed of a morning.

...

Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt were, at heart, Soldiers of the Faith. If she could call him “a very simple Christian,” he could justly say the same of her. They differed in the nature of their faiths—his grounded more in orthodox Episcopalian doctrine, hers more in her own individualized spirituality. But as fellow soldiers of the faith they could believe that they were fighting for clear and definite goals: world peace (through a United Nations organization), liberty and equality and security at home (through implementation of the Four Freedoms), and human rights around the globe (through means to be worked out after the war).

But far more than his wife’s, FDR’s faith ran up against the hard rocks of reality—of intractable circumstances, the caprices of Fortune, stubborn institutions. So he had to battle not only for a global ideology of peace and freedom but also guard the interests of his nation in a tumultuous and impious world. As a “Christian and a Democrat”—FDR’s summation of himself—he possessed a moral credo that was a patchwork of attitudes and instincts about honor, decency, good neighborliness, and noblesse oblige. But such attitudes and instincts were often hard to translate into clear directives, explicit policies, or specific operations.

The result was often a profound gap between Roosevelt’s moral code and his day-to-day practice, between his lofty ends and his dubious means, between his magnanimity and his Machiavellianism. Because men were “bad,” and would not observe their faith with the leader, “so you are not bound to keep faith with them,” the Florentine “Prince of Darkness” wrote. FDR consciously did not embrace such cynical realpolitik, but in promising the public peace, in the most cardinal case, and following measures that would lead the country into war, he had resorted to manipulation and deception. His lofty dreams and his “practical” compromises, moreover, not only collided with one another; they also inflated the significance of each other, for the higher he set his goals and the lower he pitched his improvisations, the more he widened the gap between the existing and the ideal and thus raised people’s expectations while failing to fulfill them.

If Roosevelt was both idealist and realist, the reason lay not only in his own intellectual and political habits but also in his society and its traditions. Americans have long embraced both moralistic and realistic tendencies, the first symbolized by men as diverse as Jefferson and William Jennings Bryan, the second by the “tough-minded” men—Washington, Monroe, the two Adamses—who directed the foreign policy of the republic in its early years. If Roosevelt’s goals were somewhat mixed and murky, they were shaped by liberal values and internationalist impulses so widely shared and diluted as to supply little ideological or programmatic support for politicians. Inevitably FDR faced the classic dilemma of the democratic leader: He must moralize and dramatize and simplify in order to lead the public, but in doing so he may raise false hopes and expectations, including his own, the deflation of which in the long run may lead to disillusionment and cynicism.

On the day that France was invaded by Germany, June 5,1940, a preoccupied FDR had agreed to meet once again with American youth leaders in the White House. It was a candid three-hour conversation—on a horrendous day for the world—about the critical issues facing the United States. In response to the young people’s criticism that he had abandoned the New Deal, subordinating burning social issues to the national defense, FDR thoughtfully, perhaps wistfully, invoked the memory of Lincoln.

“I think the impression was that Lincoln was a pretty sad man,” FDR told his small audience, “because he couldn’t do all he wanted to do at one time, and I think you will find examples where Lincoln had to compromise to gain a little something. He had to compromise to make a few gains.” Lincoln, he explained, was “one of those unfortunate people called a ‘politician’”—an idealist forced to play the game of compromise and pragmatism. Maybe one of the young people present “would make a much better president than I have,” FDR concluded. But “if you ever sit here you will learn that you cannot, just by shouting from the housetops, get what you want all the time.”

FDR could not escape history. American foreign policy had been shaped by two diplomatic strategies. One was a diplomacy of short-run expedience and manipulation, of balance of power and spheres of interest, of compromise and adjustment, marginal choices and limited goals. The other was a diplomacy—almost a nondiplomacy—of world unity and collective security, democratic principle and moral uplift, peaceful change and non-aggression. Too, the institutional arrangements in Washington—the separation of decision making between the State Department and the military and in their access to the White House; the absence of an integrating cabinet or staff; the institutional gaps in Congress among legislators specializing in military, foreign, and domestic policies; and indeed the whole tendency in Washington toward fragmented policy making—all reinforced the natural tendency of the president to compartmentalize.

...

The “diplomatic-political” year of 1943 posed weighty issues for FDR that variously brought out the realist and the idealist in him, or often a combination of the two.

As a leader of the “people’s war,” the president continued to put his main faith in the creation of a permanent United Nations designed to keep the peace after the war. All the Big Four leaders endorsed this visionary idea in principle; the question was where they placed it in their priority list of war goals. It was clear that the main threat to a strong UN would be the age-old carving out of spheres of interest by the big powers. Still aware that the Big Four would need to police the world for some time, the president by 1943, as historian Frank Freidel noted, was concluding that the UN should be a single worldwide body, with regional councils subordinate to it. This was a move toward Cordell Hull’s universalism. Republicans at home, under Vandenberg’s leadership, were also moving toward a stronger UN. Early in November 1943, the president led representatives of forty-four nations at the White House in signing an agreement creating the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. Nations, he proclaimed, “will learn to work together only by actually working together.”

It was the greatest concentration of power the world had ever seen, Churchill had remarked, as he looked around the conference table in Teheran in late 1943; history lay in the hands of the three leaders, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin. One evening, after sparring with Stalin and listening to Roosevelt trying to placate the Russians, Churchill was of a different mood. “Stupendous issues are unfolding before our eyes, and we are only specks of dust that have settled in the night on the map of the world.”

The three men were at the height of their brute military power. In the east, Stalin commanded the biggest infantry-tank forces ever mobilized; in Britain, Churchill and Roosevelt had marshaled the most powerful amphibious force in history. Yet both the latter men—Churchill especially—were filled with trepidation about the capacity of their armies to cross the English Channel and take on a still-mighty Wehrmacht.

The Allies were now paying the price for their two-year delay in mounting the cross-channel attack. While London and Washington were taking their time in building up their attack force, the Germans were feverishly fortifying possible invasion sectors. Hitler, now fighting a defensive war on his eastern front while trading space for time, was shifting hundreds of thousands of troops into France. A defensive system that in 1942 probably would have allowed invading forces to seize and hold staging areas in France, for further advances, was now strong enough to hold off all but the mightiest of invasions.

The Germans had made good use of their time. By the spring of 1944 they had built a vaunted “Atlantic Wall” stretching, in uneven strength, hundreds of miles from Belgium to Spain. Installing millions of underwater obstacles to smash landing craft, they had heavily mined beach areas, set up nests of barbed wire covered by carefully placed machine guns and mortars, built pillboxes and gun emplacements deep into the ground. They sought to deceive the invaders with dummy headquarters, ground movements on fake missions, and false radio reports.

But the Americans had a clear edge in technological innovation, a leadership edge provided more by civilians than soldiery. American industrialists and inventors had pioneered in a variety of weapons, but most notably in developing craft that allowed troops to cross miles of rough water, move over reefs, land vehicles safely on rocky beaches, and return. Together with the British they had developed radar, tank landing ships longer than a football field, and smaller craft, which would open bow doors, lower ramps, and disgorge masses of armor. But the true genius was Andrew Higgins, who conceived and built the famed LCVP—Landing Craft, Vehicle and Personnel—made largely of plywood, thus saving on metal, and able to run its square bow up on a beach, back off, turn in a shallow draft, and return to the mother ship for another load.

The Germans were pretty clever too. To thwart gliders, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel—the “desert fox” who had fought brilliantly in North Africa and who was now organizing German defenses against an Allied invasion—devised “asparagus”: ten-foot logs protruding from potential glider landing fields and topped with shells to smash the light craft. His technicians designed “S-mines” that jumped up and exploded at waist level. There was nothing the invading troops feared more.

Yet as a military leader, Roosevelt far outrivaled Hitler by 1944. The Führer was brilliant but erratic. He had won remarkable victories through an audacity that repeatedly caught his foe by surprise. He had shown persistence, but often to the point of irrationality, on the Eastern Front. He browbeat generals, shifted them about, and let incompetent Nazi party functionaries gain influence in the military. And strangely, in contrast to his reputation as a man of power and decision, he could be irresolute. In supervising the defense of France he had vacillated between concentrating armor near the beaches or inland and ended up by dividing his panzer divisions between both.

On military matters, FDR was orderly, focused, directive, persistent. Despite pleas to divert resources to other efforts, such as rescuing endangered nations or populations, he stuck strategically with “Atlantic First.” As commander in chief he husbanded military resources in all theaters until the enormous industrial and military power of the nation could be marshaled. Despite endless temptations to strike elsewhere, he stuck firmly to an overall strategy of the cross-channel invasion.

At the level of grand strategy, FDR’s “soldierly” qualities paid off. He helped gain a maximum Soviet contribution to the bleeding of German ground strength through military and economic aid to Moscow. He brought Allied troops into Europe at just the right time to share in—and claim—military victory. He found the right formula to obtain the most military help from the Russians without letting them, if they wished, occupy much of western Europe. He remained on good terms with his generals and admirals, encouraged them, listened to them, but always insisted on keeping the reins of top power in his own hands. He picked the right military leaders early on—Stimson and Knox in 1940, Marshall later on, MacArthur and Nimitz and Eisenhower—and stuck with them.

Normandy was the acid test of all this—and the crucial test of that test was that the cross-channel invasion was never in fact in danger of defeat. There were moments of tough decisions, of immediate peril, of second thoughts, but the invasion went on with the power and momentum of a dreadnought. The Germans fought skillfully. But they were dealing not simply with conventional invasion forces but with a tide so strong and overpowering it simply overflowed the German strongpoints and swept on. Perhaps the most telling comment came from an American infantryman.

“It seemed so organized,” said Private John Barnes of the 116th Infantry after attending a briefing, “that nothing could go wrong, nothing could stop it. It was like a train schedule; we were almost just like passengers. We were aware that there were many landing boats behind us, all lined up coming in on schedule. Nothing could stop it.”

The commander in chief was confident too, though cautiously so. While the invaders were still crossing the channel, FDR offered a D-Day prayer that asked Almighty God to lend stoutness to our sons’ arms and warned that their “road will be long and hard. For the enemy is strong. He may hurl back our forces. Success may not come with rushing speed, but we shall return again and again.”

But after furious battles and bloody stalemates on the beach the tide did move with rushing speed. With most of the Seine River bridges down and highways bombed out, the Germans had all the predictable difficulties in bringing up reinforcements. After dislodging Germans from their hedgerow defenses in Normandy, U.S. forces reached the west shore of the Cotentin Peninsula within two weeks of D-Day, captured Cherbourg a week later, and by the end of the month had landed almost a million troops, half a million tons of supplies, and more than 150,000 vehicles in France. In another two weeks the Americans had executed a wide flanking maneuver, were ready to break out from Saint-Lô, and were heading toward the liberation of Paris.

Rommel, whom Hitler had assigned to the Western Front with special responsibilities for coastal defense, had been right to believe that the first day on the beaches would be decisive. But he had been wrong, too: The decisiveness turned on countless decisions made and resources marshaled over a two-year period—above all, the decision to cross the English Channel.

...

Earlier in 1944, at a press conference, a reporter mentioned rumors in the anti-Roosevelt press that the election would be called off. “How?” the president shot back.

“Well, I don’t know. That is what I want you to tell me.”

“Well, you see,” FDR said, “you have come to the wrong place because—gosh—all these people around town haven’t read the Constitution. Unfortunately, I have.”

Hitler had evidently read the Constitution too—or at least he knew an election was approaching in November 1944. He had told his key commanders in the West, while emphasizing the vital necessity of a successful defense, that stopping the invasion would not only deliver a crushing blow to the enemy’s morale but would “prevent Roosevelt from being elected—with any luck he’d finish up in jail somewhere.”

So the president had his own two-front conflict: winning reelection while in the midst of winning a war. This was not a problem that faced Stalin, of course, or even Churchill. Britain, a seedbed of democratic practice, was postponing its general election during the war, as it had in World War I. But there was, to many americans, something almost exalted in the idea that democratic procedures must stand even in great crisis. Yet it seemed strange, too, that people united behind the supreme goal of vietory must suddenly pit gladiators against one another in the domestic arena. It soon became clear that “wartime unity” would have little impact. The 1944 election would be just as bitter and hard fought as earlier ones.

Curiously, the war against Hitlerism appeared to sharpen racism and reaction at home. Early in 1944 the president called for a soldiers’-vote bill—“the right of eleven million service people stationed around the world to cast their votes for federal candidates by name, or, if they did not know their names, by checking the party preferred.” The message hit Congress like a declaration of war. Senator Taft, his face red and his arms flailing, charged that Roosevelt was planning to line up soldiers for a fourth term as he had WPA workers for his second.

“Roosevelt says we’re letting the soldiers down,” a senator complained. “Why, God damn him. The rest of us have boys who go into the army and navy as privates and ordinary seamen and dig latrines and swab decks, and his scamps go in as lieutenant colonels and majors and lieutenants and spend their time getting medals in Hollywood. Letting the soldiers down! Why, that son of a bitch.”

Southerners feared that a soldiers’-vote act would override the poll tax and enable blacks to vote. In the House, John Rankin of Mississippi pointedly read off the names of Jewish New Yorkers backing FDR’s proposal. “Now who is behind this bill?” Rankin harangued the House. “The chief publicist is PM, the uptown edition of the Communist Daily Worker that is being financed by the tax-escaping fortune of Marshall Field the Third, and the chief broadcaster of it is Walter Winchell—alias no telling what.”

“Who is he?” asked a Republican member helpfully.

“The little kike I was telling you about the other day, who called this body the ‘House of Reprehensibles.’” Scores of members applauded Rankin at the end of his talk; no one protested.

Despite all the oratory about national unity, deep feeling against the administration was evident in the country as well as in Congress. A British observer noted that while Churchill had the backing of a united nation, FDR moved in an atmosphere of political bitterness, industrial discord, racial tension, press opposition, Democratic party defections—and of “enmity against him” of an intensity and persistence without parallel in England.

Certainly the president’s own party was in some disarray, except over the question of whether FDR should run for a fourth term. Almost all of the liberal and centrist elements in the party wanted their proved vote-getter at the head of national and state tickets. FDR was willing. Was Eleanor? “I dread another campaign,” she confessed in a letter to Lorena Hickok, “& even more another 4 years in Washington, but since he’s running for the good of the country I hope he wins.”

When FDR almost casually announced that he was available for a fourth term, there was nothing like the controversy that had boiled up over his third-term venture four years before. Still, tension remained high, not only with congressional conservatives but with leaders of the liberal wing on the Hill. It took a tax bill early in 1944 to trigger a Democratic revolt in the Senate.

For months the president had been trying to obtain a major revenue increase from Congress. The Treasury Department had estimated that in the new fiscal year income payments to individuals would run about $152 billion and that the goods and services available could absorb only about $89 billion of that figure. An inflationary gap of many billions threatened the nation’s stabilization program. As zealous as ever to be seen as “fiscally responsible,” the president pressured the congressional Big Four—Vice President Henry Wallace, Speaker Sam Rayburn, House Majority Leader John McCormack, and especially his loyal supporter Senate Majority Leader Alben Barkley—to push through a strong bill. When after Barkley’s best efforts Congress came up with an inadequate tax bill marred by provisions for “special interests,” the president dug in his heels.

He could not resist some sloganeering. It was, he said, “not a tax bill but a tax relief bill providing relief not for the needy but for the greedy.”

At this Barkley boiled over. After consulting with his wife and congressional friends, he took the Senate floor before packed galleries to denounce the president’s veto and announce his resignation as majority leader. FDR’s message, he cried, was a “calculated and deliberate assault upon the legislative integrity of every member of Congress.” The sequence was predictable. The president urged him not to resign, Barkley did so anyway, his Senate Democratic colleagues unanimously reelected him, the nation’s press was delirious over the rebuff to the president, Congress overrode his veto by heavy majorities in each house, FDR and Barkley made peace, and Barkley’s role as majority leader remained unchanged.

All was well again—except for the setback to stabilization.

...

Far more divisive even than taxes was the burning issue of FDR’s choice of running mate. The stakes were high. Many people who noticed the president’s thin face and sunken eyes—the cost to his health of wartime leadership, high blood pressure, and cigarettes—suspected that if FDR won the election he might not live to complete his fourth term. And then his running mate would be the next president of the United States. Most liberal Democrats, including Eleanor Roosevelt, asked simply, Why not keep Vice President Henry Wallace? Word leaked out that FDR was looking favorably on Hull, Barkley, Justice Douglas, Senator Harry Truman, or even an “outsider” like Ambassador Winant in London or industrialist Henry Kaiser. Names rose and fell like stocks on the Exchange. Finally, the talk turned to Harry Truman. The president liked him for his personal loyalty and legislative support even while the senator was chairing a committee that investigated governmental failures on the home front. He was a stalwart midwestern Democrat, from the politically doubtful border state of Missouri. The president did seem worried about Truman’s age and sent someone out to check it, but by the time word came back—the senator had just turned sixty—the subject seemed to have been forgotten. In the deepening haze, Harry Truman got the nod.

To symbolize his lofty position “above party politics,” FDR had taken an inspection trip across the country while the delegates nominated him and Truman in Chicago. The president accepted the nomination in a speech from a naval base in San Diego. He would not campaign in the usual sense, he told the delegates by radio. “In these days of tragic sorrow, I do not consider it fitting.” But as usual FDR left himself a way out. He would feel free to report to the people “to correct any misrepresentations.”

What about the Republicans? They were determined not to repeat the catastrophe of their 1940 convention, when party stalwarts Thomas E. Dewey and Robert A. Taft had led in the early balloting, only to be outrun on the sixth ballot by that interloper, Wendell Willkie. Now, four years later, Dewey easily won the nomination after an impressive preconvention campaign, choosing as his running mate Governor John Bricker of Ohio, a genial conservative who could placate the Republican right. “The Dewey-Bricker ticket is not going to be a pushover,” Eleanor warned in a note to her friend Joe Lash. “It is part of the fight of the future between power for big moneyed interests & govt. control & more interest on the part of the people in their govt.”

Of all his election foes, FDR had the least liking or respect for this Republican nominee. Dewey had almost beaten Herbert Lehman for the New York governorship in 1938 and had won impressively in 1942. Articulate and handsome, he had used the governorship as a dugout from which he bombarded FDR’s war leadership. Liberals scoffed at Dewey as the man on the wedding cake, the only man who could strut sitting down, the boy orator of the platitude. Publicists called him another Theodore Roosevelt, whom ten-year-old Tom and his father had backed in 1912. He was something of a look-alike, with his short bulky frame, mustache, and vim and vigor, and he represented the eastern internationalist wing of the GOP.

Nothing could have galled FDR more than this comparison. For him, Tom Dewey was no Theodore Roosevelt.

Certainly Dewey was no militant TR in the early weeks of his campaign. At the request of General Marshall, based on security grounds, he had agreed not to make the president’s advance knowledge of Japanese codes before Pearl Harbor a campaign issue, even though Dewey had learned independently of the code-breaking and viewed Roosevelt as guilty through ineptitude of enabling the Japanese to make their surprise attack. But when Dewey fell back on his basic campaign issue—FDR’s bungling leadership of the war—he won little support in the aftermath of the triumphant Normandy landing, and the advances of MacArthur and Nimitz in the Pacific.

In desperation, Dewey resorted to a device that seemed out of character for him—simple red-baiting. By the end of the campaign he had called FDR the dupe of radical labor leaders and Communists and charged flatly that “the Communists are seizing control of the New Deal, through which they aim to control the Government of the United States.” Conservative Republicans carried on this attack but made a special point of FDR’s unbridled spending. One of them, a Michigan congressman, charged that when Fala had been mistakenly left behind on one of the president’s sea voyages, a destroyer had been sent back to retrieve the Scottie at the taxpayers’ expense.

And Roosevelt? He was lying low. For many weeks he followed his traditional strategy, staying away from the campaign trail on the pretext that he was too busy with the war to do any politicking. Then, only a few weeks before election day, he opened a campaign that would become legendary in American political memory.

He began with a speech to a Teamsters union dinner. “Well, here we are together again—after four years—and what years they have been! You know, I am actually four years older, which is a fact that seems to an-noy some people,” but there were “millions of Americans who are m-o-o-r-e than eleven years older than when we started in to clean up the mess that was dumped into our laps in 1933!”

Having given poor old Herbert Hoover one more pounding, the president then lauded “the enlightened, liberal elements in the Republican Party” that were trying to bring it up to date. But the Old Guard Republicans were still in control. Could the Old Guard pass itself off as the New Deal? No “performing elephant could turn a handspring without falling flat on his back.”

Soon he had the crowd roaring, as he delivered his barbs, shifting from deadpan innocence and rolled-up eyes of mock amazement to biting ridicule to gentle sarcasm. Then came his rebuttal of the Fala story, his dagger lovingly fashioned and honed, delivered with a mock-serious face and in the quiet, sad tone of a man much abused. “These Republican leaders have not been content with attacks on me, or my wife, or on my sons. No, not content with that, they now include my little dog, Fala. Well, of course I don’t resent attacks, and my family doesn’t resent attacks, but Fala”—being Scottish—“does resent them!” Some reporters saw this as a turning point in the campaign.

Roosevelt was also determined to demolish a whispering campaign about his health. He could do this only with action, not words—most conspicuously by showing himself to millions of persons, especially in the largest city in the nation. Doffing his old gray campaign hat, under a cold pouring rain that drenched his navy cape and plastered down his hair, he drove in an open Packard through Queens to the Bronx, then to Harlem and mid-Manhattan and down Broadway. Eleanor Roosevelt was in the procession behind; at her apartment in Washington Square he rested, then returned to the drive, still under a downpour. Countless onlookers for the rest of their lives would never forget the president’s cheery face, his upflung arm and sleeve, the rain dripping off his fedora.

The legend ended with victory, FDR carrying thirty-six states, almost as many as he had won against Willkie. But there was another side to this legend.

Roosevelt had appeared to have everything going for him in this wartime election. As commander in chief he was presiding over splendid victories east and west. The country was prosperous from war spending. People could “shoot with their votes,” for nothing would have strengthened Hitler’s resolve more than the repudiation of his despised enemy. And FDR clearly outcampaigned Dewey. But FDR won the popular vote with a margin a million and a half less than in 1940. It was the closest election in popular votes since Wilson. If one in every twenty-five voters had balloted for Dewey instead, FDR would have gone down to defeat.

Why this outcome? War weariness? Too much government? Revulsion against casualties, especially following the Normandy attack? Dewey’s red-baiting? A resurgence of isolationism? Some analysts had a simpler explanation—the soldiers’ vote, or lack of it. The legislation FDR had urged was greatly weakened in Congress. Only a fraction of men and women in service actually voted. Millions of mobile war workers were disenfranchised by state restrictions requiring weeks of residence. The low voting turnout carried a message: A nation fighting for democracy had given a poor demonstration of it in 1944.

In January 1944, Franklin Roosevelt gave the most radical speech of his life, ushering in a year of his most transformational leadership. Such leadership requires a strategy of real change, embracing alterations in the well-being and happiness of a whole people, measured by their supreme historic and continuing values, expressed in their daily needs and wants, hopes and expectations—real change, executed in a planned and purposeful series of interlinked and mutually supportive actions by the whole nation.

Roosevelt a radical in the last year of his war leadership? This notion defies conventional wisdom and most historical scholarship, and the attitude of FDR himself. Did not the president himself announce the demise of “Dr. New Deal” and his replacement by “Dr. Win-the-War”? Historians have taken this switch seriously, as a natural course for a nation that had to turn from partisan New Deal reform to a united, nonpartisan, non-ideological war effort.

Little noticed have been two aspects of FDR’s famous metamorphosis. It was not a long-considered shift but an “item” that came up almost inadvertently after a press conference and that FDR felt he had to explain at the next meeting with the reporters. But his explanation consisted almost entirely of detailing how he was not abandoning the New Deal, only adding wartime “doctoring” to it. And he implied that the New Deal would need to be extended after the war.

The second factor was Eleanor Roosevelt. Within a few days of Roosevelt’s press conference she publicly disagreed—in her “My Day” column—with any dropping of “Dr. New Deal.” “I ... could not help feeling,” she wrote later, “that it was the New Deal social objectives that had fostered the spirit that would make it possible for us to fight the war.” It was obvious, she continued, that “if the world were ruled by Hitler, freedom and democracy would no longer exist.” Her views hardly surprised FDR. She had been pestering him at every opportunity to push even harder for New Deal measures—social services, civil rights, opportunities for women—during the war, and she was constantly looking ahead to the postwar world.

But it was the president himself who made clear he wished to advance, not jettison, the New Deal. He did this in his State of the Union address, January 11, 1944. He considered this speech so important that, when an attack of the “flu” (as he called it) kept him from presenting it in person, it was duly read by a clerk, with the president delivering it over the radio in the evening to reach the widest possible audience. After dealing in his usual strong terms with war issues, he suddenly switched to postwar planning at home. We could not be content, he said, with any fraction of the people, one-third or one-fifth or one-tenth, “ill-fed, ill-clothed, ill-housed, and insecure.” He briefly enumerated—and endorsed—Bill of Rights liberties but added that, as the nation and the economy had expanded, “these political rights proved inadequate to assure us equality in the pursuit of happiness.”

Then the most remarkably philosophical words from this very “pragmatic” president: True individual freedom “cannot exist without economic security and independence. ‘Necessitous men are not free men.’ People who are hungry—people who are out of a job—are the stuff of which dictatorships are made.”

He climaxed his speech with a “second Bill of Rights,” the explicit and specific rights “to a useful and remunerative job in the industries or shops or farms or mines of the Nation ... to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation... of farmers to raise and sell their products at a return which will give them and their families a decent living... of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies at home or abroad... of every family to a decent income... to adequate medical care and the opportunity to achieve and enjoy good health... to adequate protection from the economic fears of old age and sickness and accident and unemployment... to a good education.”

FDR had expanded the notion of individual rights beyond freedom of expression—and expanded, for the rest of the century, the responsibilities of the State: The government, he believed, had the obligation to guarantee citizens’ economic well-being.

During the months that followed, the president took every possible opportunity to establish these rights by executive action, explicit messages to Congress, and appeals to the people. But he did much more than this. He expressed these rights in terms of basic values, he established priorities among these values, he interlinked policies with values, and—boldest of all—he proposed a radically new political strategy.

His paramount value—his top-priority goal for Americans—was security: personal security at home and national security abroad. To advance the latter he continued to press for a strong United Nations that could enforce peace. Personal security called for millions of new jobs, governmental guarantee of employment, plus the usual “New Deal” protections of wage levels and unions. “Jobs. Jobs” FDR said to reporters. “It’s a good old Anglo-Saxon word.”

His second great value was liberty—yes, after security, because without security there could be no liberty. He would not desert the “first” Bill of Rights, however, to fight for the “second.” The needy simply were not free. Economic, social, and moral security were interlinked. And in fighting Nazism, Americans were counterattacking the ultimate in oppression, the crushing of every kind of personal, economic, and political liberty.

FDR’s third supreme value was equality, by which he meant not equality of condition but of opportunity. This constituted most of his practical domestic agenda for 1944: public health programs that would include the poor, better education especially in financially starved rural schools, extending rural electrification to poorer farm families out in the backcountry, tax policies for the needy instead of the “greedy,” a national service act that would equalize contributions to the war effort, fair employment rights for blacks. On this last count the president called for the extension and strengthening of the Fair Employment Practices Commission, but he dared not push very hard because of the FEPC’s manifest unpopularity with conservative Democrats and Republicans in Congress.

If these values, and their ordering, added up to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” this was no accident. This Jeffersonian president clothed his goals in the historic values of the great Virginian and the other founders and heroes of the onetime Republican party of Jefferson and Madison that had continued as the Democratic party of Jackson, Van Buren, and their successors. And these values were linked. Survival—order and security—first, but not at the expense of liberty and equality. He wanted, FDR said, to attain “a stronger, a happier, and a more prosperous America.”

How to achieve such magical goals? First of all, by winning elections, and FDR spent most of 1944 doing just that. But by that year he had come to realize that his goals were imperiled not just by conservative opposition but by the structure or organization of American party politics, specifically by a “four-party” system that pitted conservative Democrats allied with Republicans against a majority of Democrats allied with a few liberal Republicans. He had discovered that tinkering with the system was not enough, that sudden proposals such as his court-packing plan could miscarry, that the “purge” of 1938, and his proposed bills, failed because of the powerful alliance of southern and northern conservatives.

So it was that FDR in early summer 1944 responded to a “feeler” from Willkie, who was blocked by Tories in his own party. What about uniting liberals in both parties? FDR liked the idea, he told his political confidant Rosenman. “We ought to have two real parties—one liberal and the other conservative.” Why not start party realignment right after the election? FDR sent Rosenman to New York to work out specific plans with the 1940 GOP nominee. After a two-hour meeting Rosenman reported back to a hopeful president. But then something went wrong—worry on Willkie’s part that FDR might be using the idea as just an election-year ploy, Willkie’s diminished standing in the GOP. The two leaders agreed to wait until after the election. A month before that election, Willkie died. With his death passed an opportunity to reconstitute the very bases of American party and electoral politics.

Perhaps FDR was justified in his caution. He needed that southern Democratic vote in November. His 1944 “fighting liberalism” had run the risk of losing centrist support. He had urged a big turnout, especially by housewives and working women. He had called for a stronger soldiers’-vote bill. Over and over again he appealed to the “people,” like most candidates, but with a special urgency. As commander in chief, he said, he had no superior officer—only the people. They could command him to report for another tour of duty, or they could discharge him. In November they reenlisted him for the duration—but by so close a margin as to give FDR pause.

But the American people had done something else. If FDR had led them, they had led him, not only because he needed their votes but because they shared his vision. No one close to him expressed and symbolized the needs and hopes of the popular majority that sustained him more than Eleanor Roosevelt. While the couple’s marital relationship remained as unromantic as ever, their political and moral partnership strengthened during the war. So did FDR’s partnership with a majority of the American people.

...