Dylan:

I didn’t create Bob Dylan. Bob Dylan has always been here . . . always was. When I was a child there was Bob Dylan. And before I was born, there was Bob Dylan.

Cott:

Why did you have to play that role?

Dylan:

I’m not sure. Maybe I was best equipped to do it.

—Bob Dylan, interview with Johathan Cott, Rolling Stone, November 16, 1978

The year 1965 began with renewed hope in the nation as President Lyndon B. Johnson used the annual State of the Union address before Congress and the American people to call for turning the United States into a “Great Society,” a land of opportunity, equality, and socioeconomic progress. This new agenda, spearheaded by Johnson and primarily driven by his ambitions to reshape the country, focused on a far-reaching set of ideas that included civil rights, improving health care, reforming immigration, saving wildlife and forests, education reform, and creating a better arts infrastructure. In the speech, Johnson proclaimed:

We built this Nation to serve its people. We want to grow and build and create, but we want progress to be the servant and not the master of man. We do not intend to live in the midst of abundance, isolated from neighbors and nature, confined by blighted cities and bleak suburbs, stunted by a poverty of learning and an emptiness of leisure. The Great Society asks not how much, but how good; not only how to create wealth but how to use it; not only how fast we are going, but where we are headed. It proposes as the first test for a nation: the quality of its people.1

The goals of using national prosperity to fuel a better life were in line with the ideas at the forefront of progressive change at the time and, in fact, pushed Johnson further left than many in the country or his own party. Furthermore, Johnson seemed to be taking the nation beyond the mandates of his slain predecessor, demonstrating his commitment to improving the nation on the domestic front.2

The year also marked the reopening of the New York World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows. Running for two consecutive years, the expo once again showed visitors how the technology-based future might look. In response, millions of people flocked to the fair to see the corporate-heavy exhibits, many created in cooperation between large business entities and Walt Disney. The New York World’s Fair created a sense of unity and mission related to the future and its possibility for global cooperation, despite the ongoing challenges between the communist and noncommunist nations in such locales as the Dominican Republic and Vietnam.

Despite the hope represented by the Great Society legislative agenda and the futuristic world depicted at the New York World’s Fair, the United States plunged deeper into the Vietnam War in 1965, which undercut the optimism and kept the pressure on via the student protest movement. Many of these related impulses intersected in July when President Johnson in the span of two days both announced that the United States would increase the number of troops in Vietnam and draft more young people for the war effort, while also signing the Social Security Act of 1965 into law, which established Medicare and Medicaid. As a result, the nation seemed battling at divergent aims. On one hand, Johnson worked to keep the domestic Great Society agenda on course, but Vietnam threw a damper on the national dialogue.

Later in the summer the nation again confronted the dichotomy of its domestic progress versus international warfare when Johnson signed the Voter Rights Act into law on August 6, and on the last day of the month, signed a law that made burning one’s draft card an offense carrying a $1,000 fine and allowing imprisonment up to five years. All the while, operations in Vietnam had been increasing, including the first big American ground battle when 5,500 Marines attacked and destroyed a Viet Cong stronghold near Van Tuong in Quang Ngai Province.

The chaos on the national scene mirrors, in some ways, the turmoil going on for Dylan as he charted a new course away from being labeled a “protest” singer and pumped up as the “voice of a generation.” Obviously, it is impossible to equate the devastation of the war and its consequences on the armed forces involved with the unease Dylan felt as a single person; there were tens of thousands of people dying and many more soon would as the warfare expanded. However, it does seem difficult to completely divorce his personal agitation from what was going on around him, even if he did yearn for a way outside the labels people threw at him.

The instability of the war in Southeast Asia and the protest movement at home contrasted to some degree with the upheaval as Johnson and Congress worked to implement the Great Society legislation, which generally sought to improve the lives of Americans across a broad spectrum of education, health care, and civil rights. Within this timeframe, Dylan as an artist underwent a transformation. He replaced the working boots and blue-collar attire of his folk years with a black leather jacket and seemingly permanent Ray-Ban sunglasses. The intense, pained face on the cover of The Times They Are A-Changin’ morphed into the shaggy-haired hipster featured in the documentary Dont Look Back and the aggressive, disillusioned expression on the cover of Highway 61 Revisited.

Dylan continued his torrid writing and recording pace, releasing album after album with Bringing It All Back Home hitting the sales counters just seven months after Another Side. The new music continued the young songwriter’s evolution, pushing him closer to full-fledged rock and roll, but still clinging in many ways to his folk roots. His experimentation on this album, though, denoted a willingness to explore new genres that endures to this day. As a matter of fact, one could say that Bringing It All Back Home marked Dylan’s commitment to almost constant change and discovery. From this point on, no one could predict what kind of music Dylan would create next. He swiftly moved through rock, country, Christian, reggae, and Americana, among many others over the next five decades.

Historian Sean Wilentz indicates that the viewer can basically see Dylan in mid-transformation in the Dont Look Back documentary that filmmaker D. A. Pennebaker shot cinema verité style while the musician and his entourage toured England (Pennebaker decided to leave the apostrophe out of the title for simplicity sake). Explaining how he made the film, the director asserts, “Neither side quite knows the rules. The cameraman (myself) can only film what happens. There are no retakes. I never attempted to direct or control the action. . . . It is not my intention to extol or denounce or even explain Dylan. . . . This is only a kind of record of what happened.”3 In the midst of the “fly-on-the-wall” filming style, Pennebaker captures the singer at his feistiest, sparring verbally with British reporters and journalists and disgusted with much of what entails life on the road. Wilentz explains that the film reveals that Dylan was already “bored with his material,” but still went ahead and played the folk music, since that is what fans wanted. Overall, however, “Dylan is on the move, far beyond where some of his fans wished he would stay.”4 The next Dylan—the one that is emerging on Bringing It All Back Home—is the Ray-Ban and black leather jacket Dylan. The future will be electric!

The first side of the new record is filled with electric-infused songs that many commentators labeled “folk-rock.” Working with a house band using electric instruments, the recording sessions for the album were raucous with little or no rehearsal and little editing afterward. Dylan launched into songs and the band fought to catch up, which resulted in an alive feel to Bringing It All Back Home and fueling its energy. This manic tension is felt in “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” the first track, as well as “Maggie’s Farm” and “Outlaw Blues.” Dylan’s singing, although so removed from what he had done to that point, jumps out of the speaker, powered by the guitars and wailing harmonica.

The second side of the album is filled with acoustic, folkie-infused cuts, and features the classic “Mr. Tambourine Man,” which listeners at the time knew well from the Judy Collins version and the hit it became when covered by The Byrds. The record concluded with the ballad, “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.” The song is a kind of farewell, reacting on so many levels against the complacency of 1965, not that the timeframe was not interesting, but that the sides were drawn and the combatants seemed to be going through a dance, not actually working toward solutions. A sad song, filled with anguish, the narrator asks that the listener put all cozy notions aside, essentially building to the final image in which one simply lights it all on fire and is forced to begin all over again. Dylan could have been talking about the United States, his various relationships with women, or pointing to himself as the one who needed to burn all his old thinking to the ground.

Although Dylan realized that the popularity of the Beatles and the ensuing British invasion meant that full bands were in favor, he continued to do his traditional folk-acoustic songs. However, his discomfort for it grew as his 1964 concerts felt conventional and rote to him as a performer. At the time, he explained, he would not have even attended one of his own shows if he were just a fan. Rock music, he decided, would shake up his style and put some life back into his music. “My words are pictures,” Dylan says, “and rock’s gonna help me flesh out the colors of the pictures.”5

“Subterranean Homesick Blues” is a milestone in the direction Dylan moved toward on the new record. The song is a partnership between Dylan’s voice—short, cryptic bursts of philosophical lyrics—and the driving wail of an electric guitar and shots of harmonica punctuating the intensity. The famous opening line about Johnny being in the basement versus the narrator out on the street is more than just a great rhyme, but pokes at the idea that Dylan is worried about the government. There are plenty of other elements in the lyrics that from an overall perspective give the song a kind of conspiratorial spirit. In short order—clocking in at just under two and a half minutes—the listener meets an odd assortment of characters, from cops and district attorneys to underemployed college grads and other paranoid individuals fighting against the system. “Subterranean Homesick Blues” really is an antiestablishment song at its core, and a group of militant West Coast activists took their name—The Weathermen—from a line in the lyrics.6

The song ends with the culmination of the musical elements: a hot guitar and blasting harmonica. Simultaneously, Dylan exclaims: “The pump don’t work / ‘Cause the vandals took the handles.”7 As the music fades, it is up to the listener to determine the meaning of all this scattershot. Is the singing trickster simply telling us about a broken handle or is there some deeper meaning? Biographer Howard Sounes uncovered a bit of gossip about the song that indicates there really was a broken handle on a water pump near the area Dylan frequented in upstate New York.8 Yet, as listeners know, there is little in a Dylan song that is so forthright. Perhaps the pump stands in for the American way, which no longer works because it has been hijacked by corporations and institutions that camouflage the truth. The handle could be the American Dream itself, simply gone, whisked away by thieves in the night. Like so many Dylan songs, the interpretation is open, hinting at both straightforwardness and a deeper, trenchant vibe eviscerating American culture.

Whether it was the catchy first cut or the cumulative effect of the string of important albums, Bringing It All Back Home sold really well, reaching No. 6 on the charts, Dylan’s highest charting album to date. Folk purists may have looked at the first half of the album with more than a little derision, but music consumers snatched it up. As a matter of fact, in England, record buyers drove the album to No. 1, helped along by his short concert tour there beginning the month after its release (which became the footage for Pennebaker’s Dont Look Back, discussed earlier).9 Writer Andy Gill contrasts the reaction to the new record, explaining, “But what old folkies saw as an abject surrender of commitment to commerce, Dylan viewed more in terms of his constituency, which suddenly expanded exponentially, and his own artistic needs, which were being satisfied more completely than before.”10 Regardless of one’s position on Dylan as a genius or sellout, however, there is no way to view the era than as the artist’s complete transformation. That progression continued on Dylan’s next album, Highway 61 Revisited, which would blow audiences on both sides of the equation out of their minds.

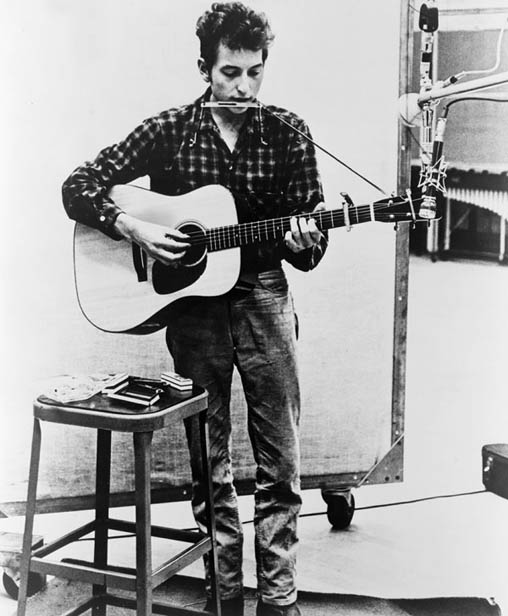

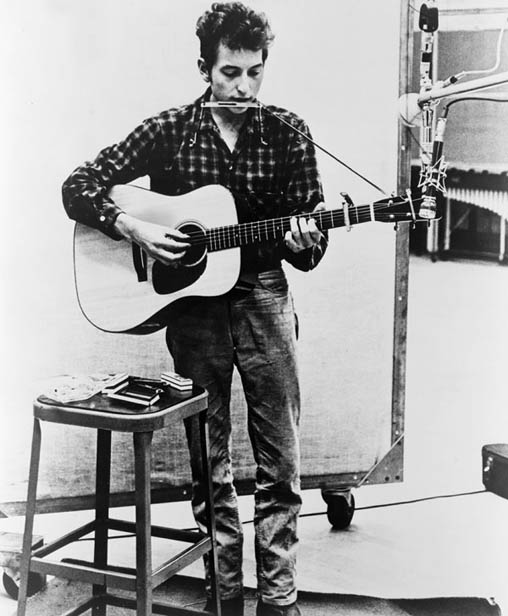

A skinny young man stands in the middle of a large room with microphones assembled all around him. He is wearing sunglasses, which occupy a large part of his face, with much of his midsection covered by an acoustic guitar. There is a contraption around his neck that looks sort of like a wire hanger contorted into a necklace. It holds a harmonica. There is a cigarette burning nearby—there is always a cigarette handy. Around the room, various musicians form an odd semicircle. They have instruments perched at their sides or on stands. The skinny guy in the dark suit with his shirt buttoned high on his neck is clearly in charge. And charge he does! The drummer cracks a note and the guitarist charges off. They all take off and the raucous sound gels into a song.

It is mid-June and the picture above is of Dylan at work in a Columbia Records recording studio in New York City. There he teamed with his long-time producer Tom Wilson and a talented group of musicians, led by Chicago blues guitarist Mike Bloomfield. What emerged over several sessions would be the record Highway 61 Revisited, which would not only set the music industry on its ear in that era, but also later grow to be considered one of the greatest albums of all time. In addition, the first single off the record, “Like a Rolling Stone,” would revolutionize its category and forever change what pop music could be. As a matter of fact, there are no longer enough accolades to encompass what this record or single meant to popular music.

Ironically, for all the retrospection accolades the single has received in the nearly 50 years since its release, “Like a Rolling Stone” never reached No. 1 on the pop charts, infamously got Dylan and his band booed at the Newport Folk Festival in late June and other performances, and got sliced up into three-minute segments by many radio stations that could not conceive of playing a song that exceeded six minutes. Thankfully, enough people heard the full-length version and called the offending stations, demanding they play the whole song. Fatefully, given that the Beatles and other bands constituting the British invasion had an impact on Dylan’s musical direction, the singe stalled out at No. 2 behind the Beatles classic “Help.”

Listening today, “Like a Rolling Stone” sounds as fierce as when Dylan recorded it. Unlike so much music then and now, it is not overproduced and schmaltzy. There is rawness in the sound that is reflected in Dylan’s voice, which at times growls, pleads, manipulates, and scoffs. What holds the song together is the sense that Dylan is reciting an epic with very contemporary themes, such as revenge, love, hate, and contempt. He mocks “Miss Lonely,” but there is a sense that the scorn erupts from a fountain of love that existed at one time. Reportedly, the song first saw life as a 20-page prose poem that Dylan whittled down into lyrics. Remarkably, the songwriter pulled off that feat without losing its power or edge. Poet and writer Daniel Mark Epstein explains the song’s connection to listeners, saying, “The song is pure theater, theater of cruelty as Dylan had studied it in the smoke-filled bars and railroad flats of Greenwich Village. It struck a chord because most of us have experienced hatred and longed for revenge.”11

“Like a Rolling Stone” is also a supreme piece of music, primarily as Mike Bloomfield’s guitar and Al Kooper’s organ work create an intricate duel, each snatching up the guts of the song and propelling it forward. Writer Andy Gill reveals its musical sense, explaining, “its rippling waves of organ, piano and guitar formed as dense and portentous a sound as anyone had dared to offer as pop, smothering listeners like quicksand, drawing them inexorably down into the song’s lyrical hell.”12 Greil Marcus, who wrote an entire book about the song, its writer, and American culture at the time, exclaims, “[W]hen the song hit the radio, when people heard it, when they discovered that it wasn’t about a band, they realized that the song did not explain itself at all, and that they didn’t care. In the wash of words and instruments, people understood that the song was a rewrite of the world itself.”13 Rewriting the world. That is quite a bit of weight to put on a song, Greil. Yet, in retrospect, the tune did revolutionize popular music and continues to influence songwriters ever since.

Riding on the success of “Like a Rolling Stone” as a single, Columbia released “Positively 4th Street” as a follow-up, although it did not appear on the album or Dylan’s next, Blonde on Blonde. The single did well for the singer, hitting the No. 7 spot in the United States and No. 8 in the United Kingdom. “Positively” is an angry song, but as typical with Dylan, the target of this ire can never be pinned down. The speculation ranges from the unidentified “Miss Lonely” of “Like a Rolling Stone” to the entire Newport Folk Festival crowd that accused him of selling out by taking up rock-and-roll music. Since Dylan once rented an apartment on Fourth Street in Greenwich Village, some find the whole folk music crowd the most compelling scapegoat. Gill says, “If Dylan’s intention was to inflict a more generalized guilt, he succeeded perfectly: everyone in the Village had the feeling he was talking about them specifically, and quite a few felt deeply hurt by the broadside.”14

The sting of “Positively” is that the target—it sounds like a man telling a woman off—is thoroughly gutted by the scorn in Dylan’s calm, intellectual evisceration. The opening line jerks the listener into the narrator’s pain. He is angry because there is a level of two-facedness going on. She was never, as he sings it, “mahh friend,” because she laughed in his face when he was knocked over. Every weak defense mounted is destroyed by Dylan’s onslaught: she never had friendship, faith, or status. Instead, she lied, gossiped, and treated the narrator with contempt. The famous final line asks that the two switch sides, then the narrator explains, she could feel how deep his hatred runs.15

Perhaps not surprisingly, when Dylan left the cozy, folk confines of the East, the tour picked up steam and support that he rails against in “Positively.” Journalist Ralph Gleason wrote about two concerts at Berkeley’s Community Theater for the San Francisco Chronicle, saying, “Dylan’s rock-and-roll band, which caused such booing and horror-show reaction at the Newport Folk Festival and elsewhere, went over in Berkeley like the discovery of gold.” He called “Rolling Stone,” an “amazing emotional experience complimenting fully the lyrics of the songs,” while “Positively” elicited “screams of joy both nights.”16 Clearly, the put-down vibes of each song took on new meaning as audiences heard them pounded out in rock and roll fashion. They signified Dylan’s move from protest anthems to personal topics that could be just as powerful and cathartic for listeners. Dylan’s transition to rock music might not have been universally praised, but the results on vinyl indicated that he would only grow more influential as he barreled across music history.

Those angered by Dylan’s new direction could not deny the power of Highway 61 Revisited. Usually, Dylan served as a stern critic of his own work. With this album, though, even he could not look askance at its quality. “I’m not gonna be able to make a record better than that one,” he explained. “Highway 61 is just too good. There’s a lot of stuff on there that I would listen to!”17 The album served up notice that America’s bard would make music that could stand with the British invaders, particularly the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. Highway 61 Revisited set a tone that embodied 1965. Nigel Williamson observes:

Performance-wise, there’s a nervous, amphetamine energy and hipper-than-thou sneer—Dylan’s words are delivered in a voice of savage cool that still pierces our complacency to this day. Adopting the position of the artist as an outsider looking in on an increasingly absurdist world, his weapons are no longer protest and righteousness but mockery and wit.18

The cover art on the double album Blonde on Blonde (BOB) features a blurry shot of Dylan in a brown suede jacket with a scarf around his neck. The out-of-focus photo masks the scornful look on his face. These seem like censuring eyes staring out at the viewer. The picture also contrasts with the music inside, which by all accounts, was some of Dylan’s most accomplished studio work, recorded with a team of highly professional session musicians in Nashville, in addition to organist Kooper and guitarist Robbie Robertson. Although the double album carried a hefty price tag, it still sold extremely well, reaching No. 9 on the U.S. charts and No. 3 in the United Kingdom. Two singles from the record charted well, with the drug-inspired (though Dylan denies it) “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35” climbing all the way to No. 2 and “I Want You” reaching No. 20.

If one interprets “Like a Rolling Stone” and “Positively 4th Street” as prime examples of Dylan’s put-down songs, then “I Want You” and “Just Like a Woman” should be viewed as examples of his great love songs. The former is unabashedly romantic, whereas the latter contains some put-down ideology, since it centers on yet another breakup. However, “Just Like a Woman” is not as vengeful as Dylan’s earlier put-down songs. Here he is willing to take some portion of the blame. The narrator reveals a vulnerability that does not exist on “Like a Rolling Stone” or “Positively.” There is plenty of room for interpretation, though, which scholars Michael Coyle and Debra Rae Cohen identify as a critical point of the album, explaining, “Dylan immerses his listeners in the twinned processes of weaving and unweaving myth—which is why the songs of BOB seem so often self-interfering and contradictory . . . BOB compels listeners to take responsibility for their own interpretations.”19

Dylan took some heat for “Just Like a Woman” from feminist groups and other commentators that felt the song demeaned women or put them down. In 2004, looking back on the track, Dylan told interviewer Robert Hilburn, “even if I could tell you what the song was about I wouldn’t. It’s up to the listener to figure out what it means to him.” Indulging the interviewer at bit, Dylan then explains, “This is a very broad song. . . . Someone may be talking about a woman, but they’re not really talking about a woman at all. You can say a lot if you use metaphors.”20

Clinton Heylin sees Dylan as closely attached to the song, saying, “Dylan felt a personal connection to this song from the first. As late as 1995 he was singing it with all the passion and persistence of a still-hungry man.”21 Philosophers Kevin Krein and Abigail Levin discuss the intersection of the personal nature of the song with its macro-level critique of materialism. Again echoing “Like a Rolling Stone,” the narrator criticizes his target for her new clothes and wealth. Krein and Levin explain that “what is problematic with this lifestyle is its inauthenticity, or to use a more colloquial phrase, its ‘phoniness.’ ”22 The ties to some brand of internal conflict within Dylan and the outward not to authenticity lead one to conclude that the ambiguous lyrics must hold deep meaning for the songwriter, despite his coy statements about its contents.

Released in January 1975, Blood on the Tracks emerged in a post-Watergate, post-Vietnam world that seemed every bit as helter-skelter as the late 1960s. Dylan had outlasted the Beatles, Elvis, and many other bands that had risen to the upper echelons of fame in his era. But, by the early to mid-1970s, young musicians were on the hunt and the press stood by eager to anoint someone the “next Bob Dylan.” Most often in their sights was New Jersey rocker Bruce Springsteen, another gritty folkish performer who seemed to rise from the streets to champion common people living normal lives and struggling to stay one step ahead of the forces beyond their control.

After years away from the music scene and what outsiders considered a series of odd career choices since Blonde on Blonde, Blood finally gave Dylan fans a powerful new sound that rivaled what he had done in the mid-1960s. Rock critic Greil Marcus, reviewing Blood at the time, called it “a great record: dark, pessimistic, and discomforting, roughly made, and filled with a deeper kind of pain than Dylan has ever revealed.”23 When it hit the record stores, fans responded enthusiastically, particularly after Planet Waves released the previous year had more or less bombed. Blood on the Tracks reached No. 1 on the U.S. chart and No. 4 on the British.

Right away, one identifies with the deep emotional material on the new album. Singer and writer Carrie Brownstein feels that Blood “leaves both the artist and the listener scarred.” Moreover, she says, “it became a love album, a salve, for his fans to sing not only to themselves but also back at him; it emboldened fans with a vocabulary.”24 Dylanologists universally proclaim that the source of Dylan’s pain in the songs on Blood is his rough relationship with his wife Sara and the breakdown of their family life (the couple had four children).

* * *

For Dylan and many fans over generations, 1965 might simply be remembered as the year of “Like a Rolling Stone.” Filled with anger and revenge (depending on which version of its creation one believes, since Dylan admits to both ideas), the song reimagined what a hit single might be in that era. Remember, the typical hit song clocked in at around three minutes long and usually told a pretty direct tale. This all changed, however, in June when Dylan’s song dropped and airplay began. Even the members of the Beatles took notice, not only of the single’s length, but also its elegant narrative.25

For all the ups and downs of 1965, from the boobirds at the Newport Folk Festival and at many performances on the subsequent tour to the success of the new, rock-driven sound on vinyl, Dylan’s work from that year is a highlight in rock-and-roll history. Some people may have not fully appreciated it at the time, because they could not understand why he moved from folk anthems to rock and roll, but for music aficionados, Dylan’s sound is legendary.

Bob Dylan in the recording studio in 1965.

(Library of Congress)

Today, Dylan’s albums from the mid-1960s rank among the best ever. For example, in 2003 Rolling Stone released a list of the top 500 albums of all time. Highway 61 Revisited turned up at No. 4, just behind Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Revolver by the Beatles and Pet Sounds by The Beach Boys. Also, charting high on the Rolling Stone survey, Bringing It All Back Home came in at No. 31.26

Even more illustrious, in 2004 Rolling Stone named “Like a Rolling Stone” the No. 1 song of all time. According to the magazine’s editors, “No other pop song has so thoroughly challenged and transformed the commercial laws and artistic conventions of its time, for all time.”27 Seven years later, U2 singer Bono, no slouch when it comes to great songwriting, extols the virtues of the song, saying that it turns “wine to vinegar” and calls it “a black eye of a pop song. The verbal pugilism on display here cracks open songwriting for a generation and leaves the listener on the canvas.” Examining it from the 21st century, Bono declares, “The tumble of words, images, ire, and spleen . . . shape-shifts easily into music forms 10 or 20 years away, like punk, grunge or hip-hop. . . . Perhaps it is a glance into the future; perhaps it’s just fiction, a screenplay distilled into one song.”28

Like so much of Dylan’s best post-protest anthem music, he mined his life, past, and the lives close to him for inspiration. The move from the macro to the personal helped establish Dylan as a poet and musician in many people’s minds. Therefore, it is not much of a stretch to see him as a novelist of music as well, particularly since the catalog of his work in the mid-1960s might have been combined into a kind of rambling, intense narrative in the spirit of a novel. Either way, Dylan’s transformation from protest poet to rock-and-roll storyteller did not diminish the view that he had important things to tell the world, regardless of whether or not electricity fueled the music.