Paul Anderson roared out of the Tennessee hill country at the same moment another deep-fried, backwoods southern country boy was roaring out of Tupelo, Mississippi. Both men would forever change their respective worlds. At the same time Paul Anderson was demolishing all strength and power preconceptions, another young man the same age, Elvis Aaron Presley, was doing likewise in his field of expertise: music. Both men emerged from total and complete rural isolation. They mysteriously developed great insight within their respective crafts. Paul and Elvis destroyed every convention, demolished everything “held most sacred,” shattered every orthodox belief, desecrated every ritual and decimated every cherished notion. Nothing would ever be the same after the appearance of these two hillbilly savants.

Barbarians at the gate: into the breach surged battalions of converts,

Emerging from swamps and backwoods,

To blow up everything held most sacred,

They sweated, roared and swaggered to the limit,

They tore down the temple and razed it to the ground.

—Nik Cohen

Nothing would ever be the same after Paul and Elvis. They were cut of the same cloth: backwoods boys, uncouth, unsophisticated hicks, off-spring of honest-to-God hillbillies. Viewed first with repugnance and yawning disdain, later with pure fear and terror, these two evoked vitriolic reactions on the part of entrenched defenders of the status quo. Unconscious revolutionaries operating in different venues, they moved mountains and changed entire worlds.

Anderson shifted the gravitational pull of his world as surely as Elvis Presley changed the musical world…irrevocably, forthwith and forever. Anderson’s world did not have the high societal profile that Elvis’ did—but that was strictly fate and circumstance, the luck of the cosmic draw. Paul had as profound an impact on all things strength-related as The King had on all things music-related. The fact that American society placed a financial premium on pop music and assigned negligible value to strength pursuits was predictable and irrelevant. That was life’s lottery.

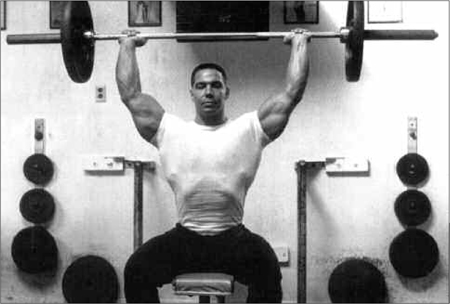

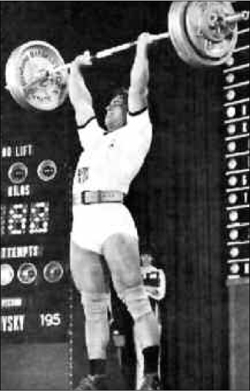

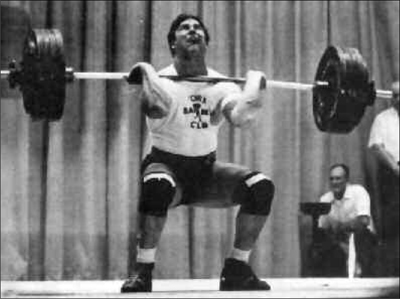

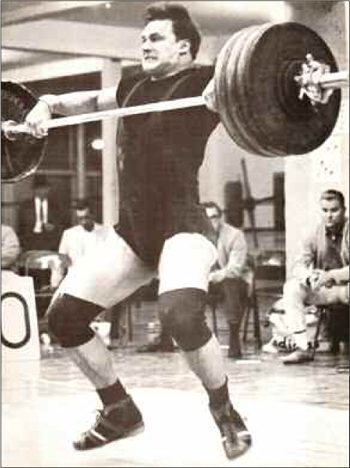

Both men died early. I saw Anderson lift in 1966 at the Silver Spring Boy’s Club. He put on a mind-blowing exhibition that changed the direction of my life. Paul began with the power clean and overhead press. He worked up to an effortless 420 pounds. The world record at the time was 418 by Russia’s Yuri Vlasov. The ease and speed of his lifting blew my young mind. His pulling techniques were awkward, yet powerful. Once he shouldered a weight, he simply lay back a tad before blasting the barbell overhead. He used none of the knee jerk trickery that eventually got the overhead press banned from Olympic lifting. Another Purposeful Primitive, Clarence Bass, recalls seeing Anderson lift in his prime:

“I saw him {Anderson} lift in 1958 at the Russian-American match held in Madison Square Garden. Anderson had turned professional by then and appeared as a special attraction. At the conclusion of the contest, the Russian champion Medvedev had pressed about 350. Anderson created a sensation by cleaning and pressing 425 for two reps and just failing with a third.”

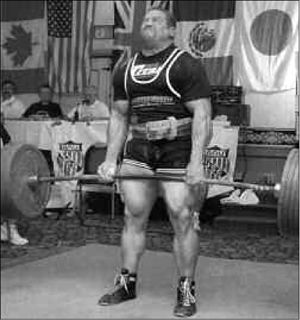

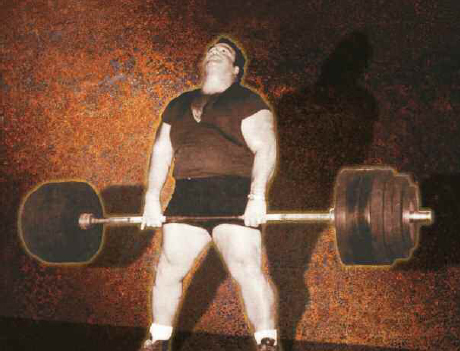

At the Silver Spring exhibition Paul wore his combat boots while pressing. Paul shed the boots and performed squats wearing black socks and a bathing suit. He used his special squat bar and wore a tee-shirt. No lifting belt for either lifts. He squatted 900 pounds for 5 reps. I thought it was the most incredible event of my life. His performance was shattering, jarring, disconcerting, unbelievable and done with eerie ease. The speed, the nonchalance with which he handled 900 was science fiction stuff. I never saw a big man squat with that velocity until Shane Hamman appeared on the power scene thirty years later.

Afterwards Paul talked about the Lord to the crowd then headed off to another whistle stop somewhere down the line. I heard he was doing four shows a week and what we witnessed required no real exertion on his part; he had many weekly shows to perform and could not afford to extend himself at any particular exhibition.

Late in his life I had the pleasure to talk with him on numerous occasions at his home in Georgia. He was stricken hard by Bright’s disease and wheelchair bound. I first interviewed him for a Muscle & Fitness feature article. He took a liking to my interview style, my knowledge of him and his career and my serious questions. I called him periodically and he liked to talk about training. He felt that he never reached his potential. During his peak physical years he traveled so much and put on so many exhibitions that he never had the opportunity to settle in and train with singular focus and purpose. He felt that had he had an inspirational goal—like lifting in the Olympic Games—he could have become much better. He applied for reinstatement prior to several Olympic Games and was always turned down flat by the steely-eyed men that ran the AAU. Had he been allowed to compete, he would have likely won the ‘60, ‘64 and ‘68 Olympics. Only the rise of Alexev could have ended his reign. His infractions, taking a few bucks for professional wrestling matches, are laughable by today’s standards.

Born 1932, Anderson won the world weightlifting title in 1955 and Olympic gold medal in 1956. As a member of the first U.S. sports team to visit the Soviet Union during the Cold War, the 5’9”, 360 pound Anderson lifted for 15,000 Muscovites on a 1955 State Department sponsored trip. Anderson shattered the world record in the press by an unprecedented 50 pounds, ramming 402 overhead in a drizzling rain. The Moscow newspapers called him “Chudo Prirody, The Wonder of Nature.” Upon returning home, he was summoned to the White House by Vice-President Nixon.

Randy Strossen wrote that Anderson’s early training was prophetic. “Paul combined short, intense workouts…throughout the day, with periods of rest. For example, he would do 10 reps in the squat with 600, rest for about 30 minutes, and then do a second set of 10. After another 30 minutes rest, he would increase the weight to 825 and do three reps, rest again and do two more reps with 845. Then he would rest again and conclude by doing half squats with 1200 for 2 or 3 reps and quarter squats with 1800. The whole routine took three hours or more. He would sip milk during the rest periods, consuming a gallon or more throughout the course of the day.”

Randy writes that Paul’s purposefully primitive extended training sessions were “Eerily prescient of what would become the structure of state-of-the-art weight lifting programs decades later. Most productive national teams train in a similar fashion, but in Anderson’s time it was unheard of. Paul Anderson’s approach was consciously developed and planned, and taken together, was quite unlike anything seen before—as were his results.”

This typical Anderson workout, circa 1955, required three to four hours to complete.

Back in the sixties, men who weight trained with any degree of seriousness practiced three separate and distinct forms of progressive resistance training: bodybuilding, powerlifting and Olympic weight-lifting.

Bodybuilding was about building muscle mass while staying lean. Powerlifting was about lifting as much as possible in the squat, bench press and deadlift. Olympic lifting was how much poundage could be hoisted overhead in the press, snatch and clean and jerk. The Amateur Athletic Union ran the Mr. America competition for forty years and controlled most local physique competitions. They awarded athletic points to physique competitors. If you wanted the extra points, you needed to demonstrate proficiency at some sport. Most bodybuilders picked Olympic lifting.

Bodybuilders entered lifting competitions to pick up those invaluable athletic points. Powerlifters of the day often were often ex-Olympic lifters who couldn’t master the subtleties of the very exacting O-lift techniques. Olympic lifters were plentiful in the sixties. Practicing the three overhead lifts produced men with thick traps, python-like erectors and rotund rhomboids. Massive backs were built by pulling on cleans and snatches; thick shoulders were built from heavy overhead pressing and jerking. Pearl came up in this cross-trained era. Genetically predisposed to thickness, he amplified his ample natural gifts.

Multiple-discipline lifting produced outstanding physiques. Men who practiced the three interrelated lifting arts, men like John Grimek, Marvin Eder and Roy Hilligen, developed incredibly rugged and functional physiques. Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sergio Oliva and Franco Columbo were later examples of Old School bodybuilders with heavy lifting backgrounds. All three were national or world level lifters before they peaked as bodybuilders.

Nowadays no one practices the three lifting arts and something has been lost. Today is the dreaded era of the resistance specialist. Physiques nowadays tend to have a predictable sameness about them. High-torque power exercises are required to develop mountainous traps, enormous erectors and overall muscle thickness. By becoming truly strong at basic compound multi-joint barbell and dumbbell exercises, muscles develop in a way unobtainable by any other mode.

Dorian Yates and Ron Coleman between them ruled the bodybuilding world for 15 consecutive years. This was largely because of their incredible leg and back development: Yates rowed with 500 for reps while Coleman deadlifted 800 for reps: there is an undeniable correlation between massive strength development and massive muscle development. Strength increases beget muscle size increases.

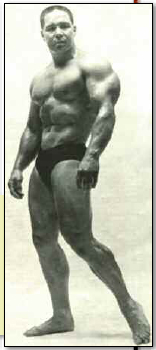

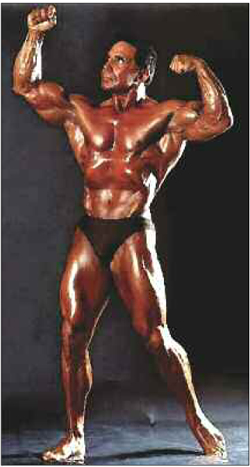

In the 1960’s two bodybuilders stood apart from the pack. Each was an immortal: England’s Reg Park and America’s Bill Pearl. Reg was God-like, Arnold’s mentor. Bill Pearl was the American Colossus. These two men took the look that John Grimek actualized and epitomized, the power look, to the next level. Both men were big men; thick, incredibly strong yet graceful. They had functional builds and were as powerful as they looked. Both were athletic. Bill squatted 600 pounds when 400 was an excellent lift. Reg bench pressed 500 when 300 was good. While the top physique competitors of the day weighed 170 to 195 pounds, Bill weighed 240 and Reg 245. Pearl’s proportions were eye-popping. Reg, slightly taller, had the shapelier physique. Reg was an Irish Wolf Hound while Pearl was a Bull Mastiff.

I idolized both of these men because they were manly and strong. Bill could tear license plates in half, bend spikes, lift up cars and rip phone books in half. Later in life I had the great fortune of meeting Bill and he was as friendly and open as I’d imagined him to be when I worshipped him from afar as a youngster. Pearl taught me a lot: he taught me there are no excuses. In order to fit training into his hectic life he would get up at 4am to work out. “I got into the habit of getting up early to train because if I waited until the rest of the world got up, there always seemed to be something happening that caused me to miss the day’s workout. I found if I took care of myself at 4am, then I was a lot better as a person when the rest of the world woke up and I had to interact with them.”

Without knowing it, he encouraged me to train early when I still worked real jobs. Eventually he unknowingly encouraged me to leave the city and move to the country. He had opted out of the lucrative rat race in order to seek the elusive, rural, “quality of life.” He was a successful gym owner in Los Angeles before he moved to the bucolic bliss of rural Oregon to live on a farm. That particular city man fantasy took root in my head and eventually I did as he did. I too bailed out of the rat race and relocated to the isolation and peace of the country.

After Bill purchased his farmette, he built an amazing gym in the barn outback. He spent his time restoring antique autos, one of his many hobbies; he was a hobbyist and had innumerable collections of old things. He also had a beautiful wife, Judy, and he was totally in love with his soul mate.

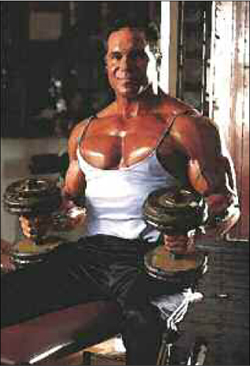

Pearl seemed genuinely happy, one of the few truly happy men I’ve ever encountered. Eventually I followed the path of Pearl, imbued and imprinted with my own subtle variations. Pearl is 20 years older than me and since 1964 he has inspired me. He continues to inspire me. He has been my iron role model and a life role model for 44 years and counting. His training, like his life, has evolved over the years. Pearl embraces change and instead of becoming fossilized and change resistant, as people do as they age, Bill remains fluid. Early on, Bill used bar-bending poundage in basic movements to build his incomparable mass and size. Once he obtained enough beef, he switched gears and concentrated on refining, honing, chiseling and defining his incredible mountain of muscle and sinew.

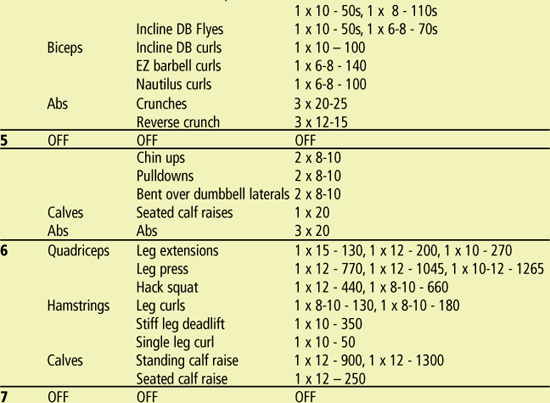

Always a training innovator, in later years he added the element of accelerated pace to his resistance training. Pearl injects a cardiovascular element onto his weight training efforts; a Pearl version of 3rd Way cardio. Sustained strength/cardio training that builds hybrid “super muscle.” Bill related to me that once he got into the swing of his two hour daily weight training regimen, his heart rate would never drop below 120 and often would spike to 170 or more. His rapid-fire workouts purposefully combine cardio training with strength training to elicit a specific effect. He no longer cared to ride the Brahma bull of huge training poundage, he had enough size. He completely changed direction. Now the name of the game was upping the intensity by moving faster during the workout. He positively devoured the time element of the training parameter. His current approach could be summarized as lots of exercises performed using pristine technique done at a blistering pace. He still burns out young training partners.

Bill is a classical bodybuilder. He is credited as the one of the first bodybuilders to create and utilize the maximum volume training approach. Bill exemplifies one extreme of the bodybuilding training paradigm while Dorian Yates exemplifies the other extreme. Pearl’s volume regimen requires the trainee perform lots of sets, reps and exercises per muscle group. Pearl typically hits a dozen or more exercises per session. He crams as many as sixty sets into each session. He hits each muscle two or three times per week. Bill never goes to failure. He talked of establishing a session rhythm; a momentum, an accelerated pace. The training partners, all following the same routine, would go one after another Bam! Bam! Bam! From commencement until conclusion, the Pearl participants are in continual rotational motion. His boys would join him at the barn at 4:30 am to commence the daily training regimen.

Bill rotated exercises religiously, periodically alternating movements to keep things fresh and vibrant. Technique is approached with reverence; making the mind-muscle connection critical. Bill stresses feel and muscular contraction and trains six days per week whereas Dorian would handle massive poundage in short, less frequent weekly sessions. Bill is a stickler for proper technique. A Pearl workout has a uniform evenness about it from start to finish. Bill wears a muscle down. Dorian knocks it out.

Now that’s one hell of a lot of work! It takes Bill over two hours to wade through this monster routine. This approach stakes out one end of the classical bodybuilder approach: Bill is maximum volume/moderate intensity. The polar opposite is Dorian Yates’ maximum intensity/moderate volume approach. Many individuals thrive using this approach. I strongly suggest using this approach when seeking to shed the maximum amount of body fat. Going fast, using modest poundage, cramming lots of exercises into a single session jives perfectly with a lean-out phase.

“The happiest man connects the morning of his life with the evening.”

—Ancient Hindu Proverb

“Curse ruthless time! Curse our mortality!

How cruelly short is the allotted time span for all which we must cram into it!”

—Winston Churchill

Bill Pearl is still important. Bill has been important for seven decades. Lately Bill is leading the charge in the battle against the ultimate foe: Father Time. Bill is 78 years old. And what makes him still so important is that Pearl is still stretching and expanding our preconceived notions about physical degeneration. Can the Grim Reaper be stiff-armed, held at arms length by a combination of weight training, diet, aerobics and stretching? Bill Pearl says yes, absolutely; and along with Jack LaLanne, he remains the age-defying posterboy.

Bill won the Mr. America title in 1955—when Dwight Eisenhower was President. That’s a hell of a long time ago. Since 1955 Pearl has been the Alpha Male statesman for bodybuilding. He’s now the ultimate tribal elder. Fifty five years ago the 23 year old Native American had just mustered out of the Navy. He entered and won the Mr. America title and proceeded to electrify the bodybuilding world. In the sixties he appeared to us mortals as the next step in the evolution of man. His girth seemed to be the next rung step up the ladder of physical perfection. Bill was thick yet symmetrical, bulky yet shapely, gargantuan yet graceful. Pearl, along with his European counterpart, Reg Park, set the philosophic tone for the sport.

The rise of Sergio Oliva and Arnold Schwarzenegger gave Bill Pearl a reason to return to the competitive battleground. In 1971 Pearl, Park and Oliva—along with Frank Zane and Dave Draper—all assembled at the N.A.A.B.A. Mr. Universe contest. Only Arnold was missing. Arnold had every intention of competing, but politics and financial commitments prevented this muscle showdown from being realized. At age 41, Pearl beat Park (past his prime) and the here-to-fore unbeatable Cuban superman, Sergio Oliva. Who would have won had Arnold entered? Pure conjecture, though in all fairness, the then 25 year old Austrian was a few years away from his all-time best condition, achieved at the South African Mr. Olympia contest. Pearl was at his physical zenith.

Pearl was on top of the World. At an age when most international level physique competitors had long since retired and were relating war stories about their glory days in smoky bars to bored bar flies, Pearl had reasserted his world dominance. He immediately retired from competition while on top. He dropped from sight, having moved from Los Angeles to Oregon.

Pearl might have dropped from sight, but he wasn’t about to stop training. Every morning at 4 he famously rolls out of bed and by 4:30 is engaged in a 2 hour workout enduro. He is a lacto-vegetarian, totally eschewing meat, and is happily dependant on eggs, vegetables, dairy and fruit juice for his dietary needs. A competitive bicycle racer at one time, Pearl used to think nothing of jumping on his bike for a thirty mile jaunt. The latest Bill is still my role model. Like a twenty foot high neon sign he projects a simple message, one exemplified by vibrancy and youthfulness that seems to say, “Look at what can be accomplished with diligence, perseverance, tenacity and intelligence. Look at how the aging process can be retarded and held at bay. Look at what is possible!”

Never before in the history of civilization have men so old looked so young. Pearl demonstrates that a man can possess the body of a much younger man if they are willing to still practice the three interrelated arts. As long as the enthusiasm and fire in the gut remains, as long as you continue to train hard and eat with discipline, you are still in the game and can still live life to its fullest. Bill Pearl is showing us how to wring every last drop of vitality and essence out of life before life inevitably expires. Long may he roll!

No athlete was ever as despised by the athletic establishment as Muhammad Ali. No athlete ever generated the venom and pure unadulterated hatred that Ali did. Even before Clay became Ali, even before he stuck his Black Muslim thumb into the collective eyeball of white America, Clay was vilified for his unrepentant braggadocio. His self-aggrandizing rhymes and poetry didn’t sit well with the lockstep white men who wore the blue blazers and ran the Amateur Athletic Union with the brutal efficiency of a totalitarian dictatorship. As the dominant sport aristocracy, they ruled all of amateur sports in this country and it was, in many ways, a reign of terror; one that would have done Stalin proud. Imperious, regal, more important than the athletes, the slightest sass, real or perceived, and the offending athlete were hauled before a Star Chamber discipline committee. Act right, the officials said, or risk suspension or permanent banishment.

Clay/Ali became the antiestablishment sports hero. “Why can’t he be a good example of his race; like that courteous Joe Lewis!” I heard one AAU official say. Worst of all, Clay/Ali began infecting other athletes. Bob Bednarski became infected. The Woonsocket Wonder crept out of Rhode Island. He’d been groomed to perfection by an amazing Olympic lift coach, Joe Mills. Bednarski commenced his rocket ride in 1963 and for five straight years he improved dramatically each and every year. He went from boy prodigy to National Champion to superstar in surreal succession.

Few men were more establishment than Bob Hoffman, founder and 100% owner of the York Barbell Club. An egomaniacal multi-millionaire, Hoffman owned American Olympic lifting. He footed the bill for teams to travel overseas and his York Barbell Lifting Club was the eternal O-lift dominator. His money made him the big swinging dick of American Olympic lifting and everyone bowed and scraped to the uber-leader who signed the paychecks and picked up the various tabs.

Hoffman entered the sixties by bringing onboard heavyweight thinkers, men like Terry Todd, Tommy Suggs and Bill Starr. These men went to work for York in different capacities at Strength & Health magazine, the bible of American Olympic lifting. When Hoffman handed the editorial reigns over to Starr, the perfect Gonzo storm occurred: the emergence of a new breed of kid Olympic lifters coincided with a burgeoning use of both recreational and performance enhancing drugs. In order to secure the talent necessary to ensure that York maintained dominance, Big Daddy had to open his wallet even wider. If they were to entice the new breed to represent York, Daddy Hoffman and John Terpak, the fierce enforcer, would need to recruit counterculture athletes.

The Chicago Y under Bob Gajda’s auspices was attracting talent and fast becoming the “anti-York.” Bill March, Tony Garcy and Joe Puleo were a bit older and already in the York fold. Peter Rawluk, Jack Hill, Bob Hise, Tom Hirtz, Frank Capsouras, Enrique Hernandez, Phil Gripaldi, Rick Holbrook, Steve Zigman, Fred Lowe, Joe Dube, Ernie Pickett and Gerry Ferrelli were on the scene and available. The King of the youth movement was Bob Bednarski. He was simply the best of a great crop: he was the most talented and the most ambitious, he was the Sun God of the new breed. Bednarski dubbed himself the Ninth Wonder of the World. His shenanigans and Ali-like traits drove Hoffman and Terpak and all the York old timers to the brink of insanity. “Why can’t he just shut his mouth and lift!” was the consensus amongst the white-bread establishment.

Bob Bednarski, the lifting Ali, worked for “The Man.” And as good as he was in Rhode Island under Mills, when he moved to York and got on the corporate payroll, he got a whole lot better real fast. They assigned him various factory jobs and asinine tasks such as mixing protein powder and bottling suntan lotion. The immortal Bill March was also a York employee and pushed Bednarski mercilessly on the lifting platform. Plus there were Dr. Ziegler’s magical little dianabol pills. Each week Bednarski grew bigger and better and stronger and faster and ever more self-assured, if that was possible.

I met Bednarski when he lifted at a competition at Gonzaga High School in 1968. Brother Don Dixon allowed me to train at Gonzaga with top local lifters like “Muscular Mickey” Collins. I became a fixture at Gonzaga. The meet turned out to be the start of Bednarski’s rampage and run to greatness. At Gonzaga he set his first World Record besting Ernie Pickett’s 446 World Record press with a 451 pound effort. I talked with him before the meet started and was awed and intimidated. I asked what he weighed and he said, “250! How do I look?!” He was obviously expecting flattery and being awestruck, I flattered until I was blue in the face. He seemed to beam. I hung out backstage, hovering on the periphery. He’d ask me to fetch him cokes. Bill March also lifted and I got to watch both men up close backstage and onstage. Because Bednarski allowed me to hover in his presence, I became a mindless lifelong groupie. I thought he was a God before I met him and after he talked to me, he walked on water as far as I was concerned. When a few months later “My Man” had his incredible lifting day in York, I was there. When he punched his 486 clean and jerk, I went into delirium tremors and almost fainted; I could not have been more affected had the Virgin Mary appeared or had Bednarski sprouted wings and suddenly started flying around the auditorium.

I followed the ever-changing training strategies Bednarski rolled through over the years that marked his tenure at York. He was innovative and hard working and since he was a heavyweight, he sought to grow ever larger in order to move more poundage. In those days, any man who weighed more than 198 pounds was forced to lift as a heavyweight (how ridiculous) and the Soviet sports armada routinely sent 350 pound monsters to do battle. Here was Bednarski, lean, athletic, good looking, brash, cocky and suggestive; doing toe-to-toe battle with the biggest, ugliest monsters the Big Red Machine could cook up in their state-supported sports laboratories. At the zenith of his amazing career he used this training template….all the work sets, top sets listed are done after ample warm-ups. This approach allows for maximum concentration on a lift.

The High Water Mark of American Olympic Lifting – June, 1968

Everything went to hell-in-a-hand basket after that glorious June day in 1968. Bednarski inexplicably didn’t make the 1968 Olympic team when at the Olympic Trials he had an off day and Joe Dube and Ernie Pickett secured the two available spots. Big Daddy pushed through the 242 pound class in 1969 and Bednarski won over a beefed up Jan Talts of the Soviet Union. But wait! After making the winning clean and jerk, the lift was then taken away by a Red Bloc-loaded jury of appeals! What the hell!? Again, bitter disappointment was snatched from the jaws of sweet victory. Eventually, years later, the gold medal was returned, but Bednarski, once again, was left with ashes in his mouth.

He returned to York and competed at the National Championships, winning yet again. The following year he took bronze at the World Championships but it was apparent something was dreadfully wrong. He was fired from York after becoming embroiled in a scandal. The vibrancy and luster was off his rose. He had a few comebacks and went on to win a few more major titles. But his glory days were gone. It was spookily akin to Ali fighting too long. He was, as super-scribe Starr wrote, “a blazing comet.” He died at age 60 of a heart attack. Barski etched a legacy that was impossible to ignore: 1969 World Champion, Silver in 1966, Bronze in 1970, no less than five National Championships, four in a row, fourteen World Records and numerous National Records. He was the Boy Sun King, the Iron Icarus that flew too close to the blazing orb, burned off his waxen wings and crashed to earth…it was one hell of a flight while he remained airborne and I shall never forget him.

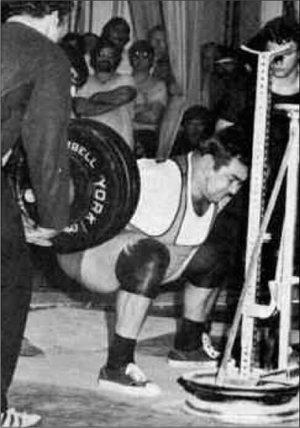

The first words Hugh Cassidy ever spoke to me were, “Hey Kid! I dig your squat style!” I was backstage at the first ever DCAAU Powerlifting Championships in 1968. I was 17 and taking my last warm-up. I knew Hugh was a pretty big deal in the then embryonic world of powerlifting. I ignominiously went on to bomb out, missing three squats with 500. I weighed 193 and insisted on starting with 500, though my best at the time was 510. I got bent forward and missed the lift on my opener. It felt heavy as hell and in those days if you missed and no one else took the same weight, you had three minutes before you had to lift it again: bip, bang, boom! Three strikes and Marty was out of the competition.

The next time I saw Hugh was on a road trip to the inaugural National Powerlifting Championships held in York, Pennsylvania in September of 1968. The trip was put together by a mutual friend, the gentlemanly Glenn Middleton. Glenn was an engineer with a huge international conglomerate and a strength aficionado who’d trained with the Schemansky brothers in Detroit. He would act as our tour director for road trips to York.

Glenn was a great lifting referee, tough and able. He was super strict and the lifters took to calling him “Dr. Red Light.” He took a shine to me and always included me in the road trips he would organize to York for the Olympic and power competitions. Hugh once said of Glenn, “The guy is brilliant; so well rounded. He’ll custom load bird shot, shoot a pheasant or brace of quail, then construct the perfect gourmet meal, cooking the birds to perfection”

Two carloads of local lifters left for York for the first ever National Powerlifting Championships; the York Picnic would be held the next day in a local park. At the competition I sat next to Hugh; he was a 242 pound lifter looking to move up to the heavyweight class. I was impressed with his methodical approach to eating. He was determined to push his weight to 300 and see what weights he would be capable of lifting. He carried a giant cooler into the auditorium. In it were a dozen sandwiches and two half gallons of milk. We sat and watched the lifting from great seats down front. Hugh would graze and munch, periodically eating a sandwich, washing it down with milk. We saw Peanuts West miss his squats and bomb out. Later, a triumphant George Frenn lifted and won at 242. During the trophy presentation Frenn physically wrested the microphone from MC Morris Weisbrott and proceeded to call forth a massively embarrassed Peanut from backstage. Frenn then launched into a fifteen minute Castro-like Peanut West soliloquy that no one in attendance will ever forget. At the time the number 1 hit on the radio was “Ode to Billy Joe.” After Frenn’s monologue, Hugh deadpanned, “Ode to Peanuts West.” I was not to see Hugh again until 1979.

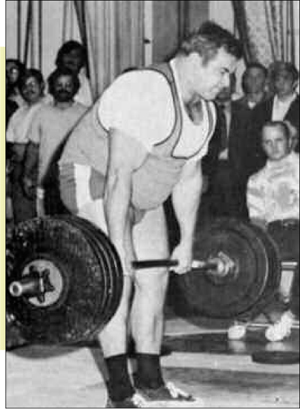

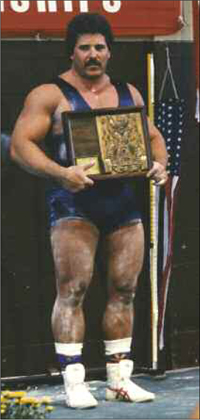

Cassidy kept eating his sandwiches and drinking milk by the gallon. His sumo wrestler approach worked: at a height of 5’11” he eventually pushed his bodyweight to 290+ pounds and shocked the powerlifting world by upsetting both Big Jim Williams and John Kuc at the first World Powerlifting Championships in 1971. Hugh squatted 800, bench pressed 570 and deadlifted 790. He lifted equipment-less: no knee wraps, no supportive gear of any type, not even a lifting belt. He injured a knee the following year and retired from powerlifting.

Being a smart man, rather than stay gargantuan, as so many lifters do, Cassidy reduced from 295 to 195 and entered a few bodybuilding competitions. He continued to train on his little farmette located off Highbridge road in Bowie, Maryland. Hugh had many interests; he taught school and had a loving wife and four kids all within a few years of each other. He left powerlifting and never looked back. In the mid-seventies a young, promising lifter named Mark Dimiduk sought out Hugh and began training under Hugh’s tutelage. Dimiduk eventually became a lifting terminator, winning the Junior Nationals, (beating Danny Wohleber) and then winning the National and World Championships. Mark began training on his own.

The hard lessons “The Duck” learned under Hugh formed the foundation for a fabulous powerlifting career. Mark squatted and deadlifted 800 and bench pressed 500 while weighing a lean and shredded 219. In 1978 I decided to begin weight training after a six year hiatus. During that time I had gotten into martial arts and trained at a facility with competitive fighters. I was bitten by the iron bug once again. After a year of generalized training, I saw an announcement in the “coming events” section of the Washington Post, Hugh Cassidy would be putting on a seminar in College Park. I attended and afterwards reintroduced myself. He remembered me. We hit it off and he invited me to train at his home gym. I stayed for many years and made fabulous progress.

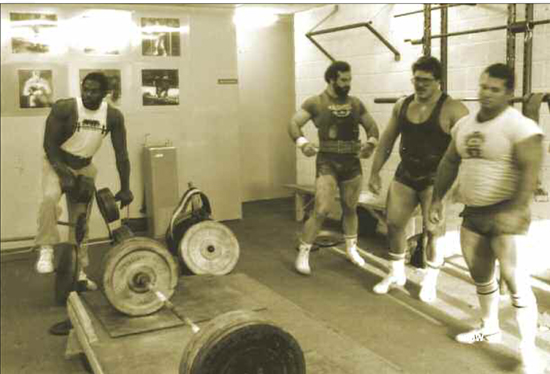

Hugh Cassidy’s basement gym looked like something from the TV show “The Munsters.” Homemade equipment (Hugh was an expert welder) was crammed and stuffed into every nook and cranny. The basement of his funky, homey, artist house had a ceiling only seven feet in height, so no standing overhead lifting was possible.

Hugh introduced me to Marshall “Doc” Peck, a semi-pro baseball pitcher who began having arm problems and switched from baseball to powerlifting. Peck eventually squatted 790, benched 530 and pulled 710 weighing 218. Hugh was training with Marshall and asked if I would like to become their third training partner. I accepted immediately.

I found Cassidy a riddle wrapped in an enigma tucked inside a paradox. He was an artist of the highest order, an excellent musician who played great guitar and exceptional bass. He worked in various bands, but opted out of the night club scene on account of his acute susceptibility to cigarette smoke. Hugh was a metal sculpture artist. He started off with simple one-dimensional wall relief tubing pieces, worked through an industrial glass table-top phase before developing refined welding techniques used on his three-dimensional nightmare creatures. Some of his devils and demons were so lifelike that they appeared ready to spring to life. As the ever eloquent Agro-American Peck once quipped, “Freaking Hugh’s monsters give me the hee-bee jee-bees!”

Cassidy might be found in his ample truck garden, grafting pear branches onto apple trees, reading classical literature or welding art. He taught special needs children and had more mental horsepower and artistic creativity than any athlete I ever met, before or since. He was directly responsible for starting me off on my writing career when he graciously consented to co-author some powerlifting pieces. He was tough on me and had trouble with my “bombastic” style. He was on us hard in the weight room. We trained twice a week and slammed down calories to speed recovery on the in between days. Hugh’s approach could be summarized thusly: train like a psycho, eat everything in sight, rest up and grow gargantuan. For young testosterone-laden men seeking size, strength and power his minimalist approach was magical.

We would start our Saturday enduro with squats and work up to a top set. Depending on what phase of the overall training ‘cycle’ we were in, the top set could be 8 reps, 5 reps or 3 reps. 8 rep sets were done for four straight weeks, starting 12 weeks prior to competing. Eight weeks out we’d shift to 5 rep sets. For the final four weeks leading up to the competition, the top sets were dropped to triples or doubles. Ditto for the all important back-off sets: these were done with lighter poundage.

Peck and I would wear knee wraps and a belt working up to the top set. Then take off the wraps and belt for the three back-off sets of 10 reps, 8 reps or 5 reps. The back-off sets were done with a considerably lighter weight than the belt/wrap top set. Pumped to the max after the squat back-offs, we would shift to bench pressing and repeat the same procedure: work up to a top set of 8, 5 or 3, then three sets of back-offs. After benching, our legs and lower back were somewhat recovered, so it was on to deadlifts. Again, work up to a top set, then three sets of back-offs. Hugh would have us do ‘stiff leg deadlifts’ on the backoff sets. Then for desert 3-6 sets of “arms” usually super-setting curls with triceps presses or pushdowns.

For a while Hugh got on a “heave” kick, which was sort of a massive high pull done with a lot of weight while trying to generate momentum at the top. When he’d insert these after deadlifts we’d groan. We would repeat the whole deal 3-4 days later. It would take us hours to get though this workout. Often I’d have to lie down before I had the strength to drive home. Peck and I would stop at the 7-11, buy a half gallon of ice cold whole milk (each) to drink on the ride home. Milk never tasted as good as it did after an August training session in the dungeon with only a single plastic fan to keep us from keeling over. Hugh would tell us when we complained of tiredness to fire down more calories. “Eat your way through sticking points!” He’d say. If the poundage was feeling heavy on Saturday weighing 216, push your bodyweight to 220 by Wednesday and make those weights seem light. This was a man-killer approach: train till you begin hallucinating, eat tons of food, drink four quarts or more of milk daily then rest until the 2nd weekly slaughter fest. This approach worked wonders for aggressive young men intent on becoming massively muscled competitive powerlifters. Hugh was a ‘psyche up’ master and could visibly manifest his internal psyche by the use of what he called “cooling breaths.” He was able to make this happen at will.

“I cannot explain it psychologically, but I have found that if I expel my breath in sharp gasps I get goose pimples all over my body. In this condition I lift far more in meets than in training, averaging 40 pounds above my best training effort for both the squat and deadlift.”

Cassidy was one of a kind: brilliant, moody, insightful, soulful, introverted and sensitive. My time with him laid a foundation of hardcore training that has served me well ever since. Never was the adage, “hard work pays off” more apparent then in his take-no-prisoners, ultra-simplistic, Purposefully Primitive approach that he exemplified and taught. Nowadays most lifters under-eat and under-train: many are vain surface-skimmers with low pain tolerance and lots of self-esteem. The Old School approach of train-till-you-drop is politically incorrect and even suggesting it to the new breed is a waste of breath. I have often thought that if I ever wanted to train a kid powerlifter to become a world beater, I would draft one of those X-Game skateboarders or motocross kids that do those death-defying jumps. I think that powerlifters and lifters of my generation had that same crazed mindset. Nowadays fanatical types participate in other sports.

Going from training with Hugh Cassidy to training with Mark Chaillet was like being paroled from a Georgia chain gang to go live in a luxury spa. Not that training with Mark was easy or breezy, but Chaillet’s Gym was a terrific facility, easily the best gym I’ve ever belonged to. The people were incredible and the place was heated and air conditioned. I made Mark’s gym my second home for six straight years.

Marshall Peck and I were training with Hugh when we got wind that Mark Chaillet, already a power legend, would be relocating back to Temple Hills, where he was from originally. He would be opening a new gym dedicated to power and strength. Marshall and I were ecstatic. We had Hugh’s blessing; we both had worked hard, made great progress on every front in every way, but Hugh agreed: our strength levels were making it apparent that it was time for a change. At Hugh’s we used a 6’ exercise bar and had taken to hanging dumbbells attached with coat hangers on each end of the bar to get over 600 for squats.

Chaillet had been working for power God, Larry Pacifico, in Dayton for the several years. Larry “drafted” the finest young powerlifters from around the country to help him staff his empire of gyms and spas. At different times Larry had Mike Bridges, Mark, Joe Ladiner, John Topsoglu, and a whole host of other young power prodigies working for him. Mark decided to move back home and open a gym. He found a space overtop of an auto parts store. Mark’s dad, Buck, a salty ex-DC cop, helped Mark build out the space and run the gym.

Buck didn’t like too many people but he took a shine to me. I hit it off with the whole family, Mark’s mom, his brother Ray, his sister, his wife Ellen, these were great people, my second family. Mark became as close to me as a brother and I cut my big league coaching teeth handling Mark at National and World Championships. Marshall and I moved to Mark’s and joined up with the most amazing assortment of power athletes I’ve ever had the pleasure of training with, before or since.

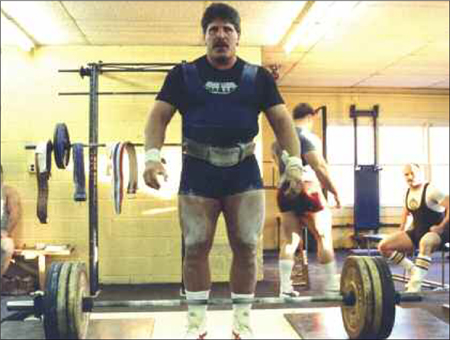

Everyone made progress fast training at Chaillet’s Gym. A communal strength synergy took hold and each week we all seemed to get bigger and stronger. Seeing guys routinely squat 900, deadlift 800 and bench press 600 raises your game. Being a big fish in a small pond is illusory and stunting. Chaillet’s was a powerlift reality gut-check: a big pond full of big powerful fish.

It always seemed to me that Mark Chaillet really didn’t like training all that much. Or perhaps to put a finer point on it, Mark didn’t seem to like training in any way other than one way. He stuck with his particular, peculiar style of training for the six years I was his training partner. In a nutshell, twice a week he would have a mini-powerlifting competition. Mark would work up to a single, all out repetition in each of the three lifts wearing all his power gear. That was it. Monday at 4pm was squat and bench press day. Thursday at 4pm was deadlift day. I can count on the fingers of one hand the number of times over the years I saw him do any lift or exercise other than the three powerlifts. Every once in a blue moon I might see him perform a set of curls, or do a set of stiff leg deadlifts, but nothing consistent other than the big three.

Typically at the appointed time on Monday and Thursday, a crowd of lifters would show up to train either the squat/bench or deadlift. By crowd, I mean a crowd! Three platforms or benches would all be going at once. Mike Benardon, Don Mills, Joe Ferry, Bob Brandon, Marshall Peck, Jeff Bobalouch, Kirk Karwoski, Frank Hottendorf, Mark Dimiduk, Ray Evans, Ray Chaillet, Bob Bradley, Big John Studd, Graham Bartholomew, Ray Hager, Big Buddy, Noah Stern, Larry Christ, Elliot Smith, Bob Snell, Greg Tayman…on and on… on one Thursday I counted thirteen men in the room, all of whom had deadlifted 700 pounds or more.

The procedure would be as follows: on squat day, the power rack that faced the rear wall would be used by Mark and the four other heaviest squatters in the room. This group would be the 750+ guys. On the second set of squat racks, facing the deadlift platform, the 600 to 750 pound men would set up shop. On a third set of racks, facing the wall adjacent to the bathroom entrance, the smaller guys, the 400 to 600 pound club, would squat. After squats, three benches would be set up, each handling a certain poundage range. On Thursday, deadlift day, the 700 plus guys lifted on the elevated main deadlift platform. The 600 to 700 range men would lift on the adjacent floor area and the up to 600 men would lift in the area by the bathroom. It was the most simplistic power and strength program I’ve ever been exposed to, before or since.

In mainstream powerlifting orthodoxy, making the single repetition the backbone of a training strategy is viewed as insanity. At Chaillet’s the single rep was a religion.

Mark used the classical 12 week periodization cycle that was so in vogue back in the 80’s and so out of vogue today. Typically Mark would take about four weeks to ramp things up. Eight weeks before the National Championships he would get real serious and the weights would start to fly. I was intimately involved in helping him plot out the cycle and in making any in-flight corrections as circumstance warranted. I am going to do this from memory so it might not be exact, but will give the reader a real sense of how a stud like Chaillet would peak his mind and body leading up to a championship. The real work would begin after four weeks of getting into decent shape.

Mark might start the 8 week cycle off weighing a soft 255 and by the competition he’d weigh a rock hard 280 and lift weighing 275. He was a tremendous competition lifter who routinely would come back after being behind 100 or 200 pounds at the sub-total (the combination of a man’s top squat and top bench press poundage) before decimating the competition. He would take a token opener in the deadlift of say 760 then turn to me and say, “Add it up—how much do we need—can we win?” If it was anything up to 860, the leader was dead.

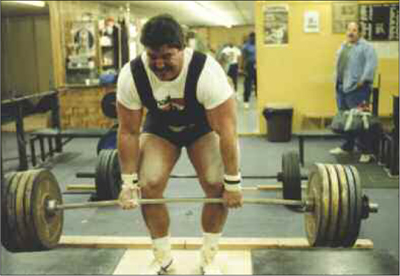

He was the greatest conventional deadlifter I’ve ever had the pleasure of training with. Mark pulled 880 and had 900 within three inches of lock-out. He consistently could deadlift 840 to 860. Mark occasionally would do some stiff-legged deadlifts using 800. One afternoon, I saw him pull 835 standing atop a 100 pound barbell plate laid flat. His minimalist approach worked phenomenally well for him for almost a decade. I think that those who dismiss his approach are short-sighted. Plus, I don’t see very many 269 pound men deadlifting 880 nowadays. Mark squatted an IPF legal depth 1000 in training. By legal I mean deep. I called him up on the depth on that very lift. He officially hit 940 wearing one of those old Zangas Supersuits, no briefs and legal length wraps. When it came to leg and (especially) back power, Mark Chaillet was “cock strong.”

They’ll be saints and sinners,

Losers and winners,

All kinds of people you ain’t never seen

—The Band

The stories about Chaillet’s Gym are so outrageous that they have taken on mythical proportions. I called Mark’s gym “The House of Pain” in a Powerlifting USA article and for good reason; at Chaillet’s I’ve seen beat-downs and sex between patrons, I’ve seen illegal activity and acts of heroism—sometimes all on the same afternoon. I will recount a few that come to mind. The names have been changed to protect the guilty.

The gym had a gun bin and clients were required to pass weaponry across the front desk to either Mark or Buck—no questions asked. A towel was draped over the firearm as it was passed. Serious powerlifting, competitive powerlifting, at least in the 1980s, attracted a large contingent of both police officers and career criminals. Mark’s gym bumped up against a bad section of the city and the cocaine trade was keeping both cops and crooks active. One afternoon, one of the best training partners I ever had, a deep cover narcotics officer, nudged me and gestured towards a good looking young fellow spotting a monstrous man with jail tattoos bench pressing 500 for reps. “That’s _______ ________. He controls the coke trade in all of Southeast DC.”

Interestingly, my cop pal, the coke kingpin, and his muscleman protector/bodyguard, were super cordial to each other. My man explained. “His sources have fingered me. So since he knows I’m a narc, he wants to make nice out of professional courtesy.” A few years later the DEA arrested the young King Pin and found close to three million in cash. He had two money counting machines in his luxury condo. They sent his whole family up the river including his grandmother.

Chaillet’s Gym was like Ric’s Café in Casblanca: beefs and vendettas were usually left at the front door. Once you walked up the stairs and turned in your Glock or Berretta, you were no longer a lawman or lawbreaker, you were a powerlifter. During one period I trained with a DC undercover cop and a Baltimore cocaine ring enforcer who later went into witness protection. Neither knew the others man’s trade. No one asked personal stuff. I overheard the coke enforcer mention he had some fully automatic AR-style machine guns for sale. The undercover cop wasn’t interested in busting the guy; he wanted the rife for his own private collection and didn’t want to go through the legal paperwork. The coke enforcer said he happened to have one in the trunk of his Cadillac and after the workout he’d “front it” to my cop pal and, “since you’re a friend of Marty, you can pay me later.” I stepped in and told each (separately) that this was a real bad idea. Ironically both men eventually landed in jail for long stretches: 20 years apiece.

Doug Furnas was above all else an athlete. He was one of the true strength giants of our time, but being a hall of fame powerlifter was just one aspect of the Ice Man’s extensive athletic career. He had a steely competitive demeanor, a savage work ethic and tremendous genetic gifts. He was successful in every athletic undertaking. Doug never reached his full potential in any one athletic arena because he would periodically spin off in another direction: from rodeo to football to powerlifting to strongman to professional wrestling… he was an athletic Ronin Samurai warrior. “This gun for hire.” He could have gone professional as a teen rodeo rider; he was starting fullback for a high school team that played in the State Championships; he played for the National Champion junior college football team before becoming a starting fullback for Tennessee on a team that included pro football immortal Reggie White. He played in the Peach Bowl. He played pro football for Denver with John Elway before taking up powerlifting.

He set his first World Record within nine months of dedicating himself exclusively to the sport. He ripped across the power skyline for four years before becoming a professional wrestler. He was a veritable wrestling God in Japan. During the late 1980’s he was recognized everywhere he went in Japan and mobbed on the streets like a rock star. He wrestled in the WWF before an auto accident ended his athletic career. Doug was unquestionably one of the most innovative resistance trainers of the modern era. I am proud to call him a friend.

Doug Furnas was sophisticated in his strength philosophies and put theory into practice with incredible results. He had the good powerlift luck to stand on the shoulders of another iron giant, Dennis Wright. At a critical juncture in his multidimensional athletic career, Doug studied powerlifting under Dennis like Luke studied under Obi Wan. When Dennis slipped the leash, Doug squatted 881 weighing 238, using the most awesome squat technique ever seen. His squats were like Raphael paintings, as athletically exquisite as a Tiger Woods golf swing or a Michael Jordon leap-and-dunk. Doug had great mentors at various times in his athletic career, but none were more accomplished than Dennis.

Furnas excelled at every athletic activity to which he turned his full attention. He competed at stratospheric levels in every sport: starting off with rodeo as a man-child, then football, powerlifting and finally professional wrestling. He and wrestling partner Phil LaFon were five time tag team champions in the All Japan Professional Wrestling federation. Later he and tag team partner Don Keffutt captured the ECW World Tag Team title.

Doug’s only athletic disappointment occurred when a hamstring injury prematurely ended his professional football career with Denver. The injury effectively strangled his pro ball career in its crib. He became disillusioned and was relegated to the Bronco taxi squad. For the first time in his life, he was not a starter or a star. His hamstring injury became a chronic injury and he became embroiled in irresolvable conflicts with Denver head coach Dan Reeves. He was trapped in athletic limbo: good enough to be kept on the payroll, never healed enough to demonstrate his wares, increasingly frustrated and disgusted, he headed home to the family farm to reconsider his future and athletically recalibrate. Football’s loss became powerlifting’s gain.

Doug’s love affair with a barbell commenced after he was nearly killed in a horrific auto accident. The Furnas family was returning home from a rodeo competition when their car was run into head on as they crested a hill by a drunk driver speeding down the wrong side of the road. Doug was 16 at the time. His body was completely shattered. Both his legs were broken, his shoulder was destroyed and his spleen exploded upon impact. Doug’s father broke his neck. His girlfriend (who he later married) broke her back. Doug’s mother broke both ankles.

It took him almost two years to heal. Lifting weights became a big part of his recovery and he developed a deep taste for weight training. He recovered enough to go back to school. His younger brother Mike and he were now in the same grade. All through junior high school, high school, junior college and college the two played together on championship football teams. The brothers played on a high school team that went to the Oklahoma High School State Championships. Both were selected as Oklahoma high school all-stars and played against the Texas all-stars in the Oil Bowl. Both played for Northeastern Oklahoma A&M, a junior college squad that won the Junior College National Championship.

That brought dozens of offers from Division I teams. The brothers decided on Tennessee because both were offered scholarships and they could continue to play together. Tennessee won the conference title and went to the Peach Bowl. On New Year’s Day in front of 60,000 people, while millions more watched on TV, Tennessee lost by two points to Iowa 26 to 24 in the last 60 seconds of the game. Though he didn’t know it at the time, that exciting loss would be both the high point and the tragic foreshadowing that the football high times had peaked and things were about to sour. Doug ended up with the Denver Broncos and after a hamstring injury became chronic, he voluntarily opted out. Doug was now free to immerse himself in powerlifting. He had followed the iron sport since his auto accident and dreamed of a time when he could focus on it exclusively. That time was now.

For the first time since third grade, Doug wasn’t participating in a team sport. With powerlifting it was just him and the barbell and the aloneness appealed to him mightily. Now he didn’t have to schedule his life around someone else’s practice schedule. Now he could concentrate 100% of his energies on an individual sport. He would settle in and concentrate on becoming the best powerlifter he could be. His brother joined him. Now they would both commence on the powerlifting path, together once again.

He had followed the sport of powerlifting all through high school and college. He was particularly taken by another amazing athlete turned powerlifter, John Gamble. The monstrous Gamble had it all: massive and lean, John had a ferocious competitive attitude. Gamble was a balanced lifter who at his peak was untouchable. Gamble had an incredible physique and his sheer physical dominance provided Doug with a power role model, someone he aspired to emulate.

Doug compounded his physical and psychological assets with clean living habits; he neither smoked nor drank nor partied. He had a stern, collected, Ice Man demeanor. He seemed aloof because he was aloof. If you were in his inner circle he could be quite open and humorous. He was well spoken, but soft spoken and you would find yourself leaning forward to hear him better in conversations. From a distance he appeared humorless; he was the kind of guy if you were competing against you hated, but he was exactly the type of man you would want in a foxhole next to you. It was easy to envision him as a squadron commander leading a mass assault of M-1 Abram tanks across some desert landscape. After the extreme regimentation of football, dealing with coaches who held scholarships or money over his head, Doug was glad to be free of the smothering, all-consuming commitments of big time football.

He sought to maximize his abilities as a lifter. As a teen he had apprenticed under Okie powerlifting legend, Dennis Wright. Both men lived in the same neck of the woods in rural Oklahoma and it was only natural that Doug and Mike and Dennis begin working out together. Dennis would power through his own sessions and Doug and his brother would “ghost Dennis,” following right behind, performing whatever exercises, set and rep selections Dennis decided upon. Doug and Mike would tackle whatever Wright set in front of them, no questions asked.

In the early days, Doug and Mike would powerlift between football seasons. After pro football, powerlifting was given undivided attention. It was the beginning of a legendary run of the table. Furnas’ power career lasted four short years, but during that time he was a meteor streaking across the dark sky of powerlifting. He redefined the athletic possibilities. He campaigned for a season in the 242 pound class and set his first world squat record, 881 pounds, weighing 239. Standing 5’10” he was actually too tall for that class and really hit his stride when he moved up to the 275 pound class. He had played football weighing a leaned-out, trimmed to the max 225 pounds carrying a 6% body fat percentile. He was a blocking fullback who ran a 4.5 forty and had a 40 inch vertical leap. Adding 50 pounds of muscle caused him to come on strong and fast.

Furnas was the powerlifting equivalent of the perfect storm: great genetics combined with a great work ethic, a high pain tolerance and a hall-of-fame coach. Wright pointed out all the shortcuts and dead-ends ahead of time. Wright’s primordial approach, lots of volume, lots of poundage, lots of sets and long sessions, was Old School all the way. No-mercy power training for those who could hang. The Wright/Furnas brother training sessions were legendary. The Furnas boys had highly developed pain tolerances from all those rodeo bumps and bruises, all those football practices, and before all of it, from the hard farm labor they were required to do as youngsters. Doug and Mike were subjected to the hardening effects of intense manual labor as children.

The family owned a 270 acre ranch and the boys were required to work and work hard. Mike was a year younger than Doug and just as athletic and just as combative. Doug related that as children the brothers were expected to “pull their weight” insofar as chores. When they were youngsters the duo were assigned to work together. The duo was expected to perform the work of a single adult male farmhand. Together they formed a “unit.” Together the two little boys would run along in open farm fields, behind a moving truck, together dragging 100 pound hay bails up to a moving flatbed. They would routinely carry heavy water and heavy feed buckets. They worked long hours at physically demanding tasks. Meanwhile, Doug noted, that “while Mike and I were wrestling steers and each other, the town kids were out playing T-ball.”

The brothers became “real physical” and when the twosome started playing high school football they were way ahead of their teammates. Football, however, was not the first sport young Doug excelled at: the entire Furnas family competed on the competitive rodeo circuit. They paid substantial entry fees to compete for cash prizes. Mom, dad, brother, sister, all rode and roped, competing for money. Hardcore rodeo taught Doug how to fall, how to get thrown and not get hurt; how to get up after being thrown, how to dust yourself off and shake off the pain. He gave serious thought to becoming a bull riding professional; his childhood rodeo contemporaries founded the Professional Rodeo circuit.

Forced to make a choice, Doug choose football. He ended up as a teammate of NFL all-pro and World Champion sprinter Willie Gault. Also on the Tennessee team was future Super Bowl MVP, NFL Defensive Player of the year and Hall of Fame immortal Reggie White. Doug and Mike Furnas effortlessly operated at the highest athletic levels.

Dennis Wright was a hall-of-fame powerlifter who got better as he got older. Dennis started off in the 70’s as a gangly, yet surprisingly powerful 165 pound lifter. I saw him lift at age 50 and weighing 198 pounds. Dennis squatted 800 pounds, quadruple bodyweight, in exquisite fashion. He backed up the squat with a 475 pound bench press. The 800 pound squat was pure technical perfection. After a slow, controlled descent that ended in a precision turn-around, two inches below parallel, the ascent was explosive and crisp. Watching Wright’s lifts that day, I was struck that every squat he took was an identical copy of the previous one or the subsequent one. I was seeing a Samurai master handle an o-dachi long sword.

Doug related that he and his brother always made it a point to arrive for training sessions with Dennis 15 minutes early. They would sit curbside in the car until the appointed training time, drinking coffee. The brothers would fire each other up as they sat, talking themselves into a quiet frenzy, getting psyched for the workout. I asked, why they didn’t just go in early, or arrive on time. Why arrive early? I asked. “We were showing Dennis respect. We made it a point to arrive early in order to show our eagerness and gratitude. Going in early would have been disrespectful.”

Dennis Wright would work the hell out the brothers during a session. A typical weekly squat week would find the men performing four sets of 5 reps on Tuesday with a “static” poundage. On Saturday they would work up to a heavy 5 rep set, then a heavy 4 rep set, then a triple, then a double and finally a single. Not done they would “back down,” i.e., reduce the poundage, and hit sets of either 5 or 7 second pause squats. “Dennis was a simplistic genius. Everything I have ever done was a result of what I learned from him.” More Furnasian deference.

When Doug began concentrating on powerlifting his poundage began to soar and he dropped the twice-a-week squat template. “I wasn’t recovering session to session. I played with a second “light” squat day, but that seemed like a waste of time. Eventually I dropped the second weekly squat day—and that’s when my lifting took off.”

In each session they would strive to equal or exceed previous personal records, though capacity might take differing forms. As a result of all the Old School squatting and pause squatting, done Dennis Wright style, (lots of volume, lots of intensity, lots of poundage) Doug grew gargantuan legs. It was said that his thighs measured 34 inches while his waist size was 34. He refused all inquiries into his girth measurements. Eventually, he weighed 275 pounds, yet was ripped and shredded. Even at his heaviest bodyweight he was always lean and athletic. He bench pressed 620 in training and 600 officially, this while wearing a loose, size 60 inch 1st generation Inzer power shirt. His shirts were so loose I asked why he bothered wearing them at all; he could put the shirt on himself. “I like the way it keeps my torso warm.”

Dennis Wright was a great bench presser and gave the Furnas Brothers a template that mined the same training vein as the squat: work up to the target poundage, always stressing perfect technique. They would perform bench press “assistance work” and followed an axiom Hugh Cassidy passed along to me: the best assistance exercise for a particular lift is an assistance exercise that most closely resembles the lift itself. Therefore the best assistance exercise for the flat bench press would be more flat bench presses using a wider or narrower grip. Dennis passed onto Doug a bench system that Doug modified and eventually perfected.

A typical Furnas bench workout might find him working up to a top set, before cutting the weight and performing two sets of wide grip bench presses using a pause on the chest. Then he would drop the poundage and hit two sets of flat bench presses using a narrow grip. Narrow grip bench presses would also be paused. With narrow grip benches the sticking point occurs as the bar approaches lock-out and concentrated use of narrow grips improves lockout ability. Wide-grip bench presses were purposefully paused to build “starting power.” Triceps would be worked hard after benching.

Doug used a sumo deadlift technique and tried to harness his amazing leg strength in his pulling. He viewed the deadlift as a “reverse squat.” He used a wide stance in both lifts and maintained a bolt upright torso. He never let his hips rise to get the deadlift started and eventually pulled 826. His deadlift limitation was his grip. He had violent allergic reactions to magnesium carbonate, lifting chalk, and this meant he had to pull without it. Doug found that if he successfully pushed his squat upward, his deadlift would tag along. There was a consistent ratio between the two lifts and as he approached 1,000 in the squat, his deadlift rose proportionally.

Incredible Eddy Coan shared training ideas with Doug on a regular basis. The two saw eye to eye on so many areas that they arrived eventually at a power training consensus. Their template was adopted by many of their contemporaries and changed the power thinking of the day. It was an amalgamation, a blending of strategies that amplified results. In person they were impressive: Doug’s persona, quiet intensity, made an interesting contrast to Ed’s Irish fierceness and fire. Like Mick and Keith, John and Paul, Butch and Sundance, they became Iron partners. There was a period of time when the two were inseparable at National and World competitions.

After retiring from powerlifting, Doug kept his hand in the game by coming to the Nationals to work with Ed Coan. I had the pleasure of coaching each man at National and World Championships. It was a white-knuckle, hair raising experience to work with these guys. It was terrifying to handle Doug, Ed and Mark Chaillet—all at the same time! Any mess up and months of work could be destroyed.

What a trio: each man needed special handling. With six months of preparatory blood, sweat, tears and training preparation on the line, coaching these men on report card day was no freaking joke! These guys were all business on game day. They only competed twice a year—at the National Championships and at the World Championships—so there was a helluva a lot at stake. When these big guns, the biggest stars in the sport, were rolled out together, world record smashing was expected and demanded.

My job was akin to that of a NASCAR pit crew chief handing three racecars at once: it was up to me to time the process, ensure that all warm-up attempts were done in a timely fashion, make sure the backstage warm-up poundage was loaded correctly, that spotters were in place and alert. Gear needed to be put on at just the right time: wrap a man’s knees too early and kiss the lift goodbye. The wrap tension will cut off blood circulation and turn a man’s legs blue. Start the knee wrapping procedure too late and the lifter is rushed and hustled onto the platform, deprived of his critical pre-lift psyche-up. At worst, late wrapping causes the lifter to be “timed out,” disqualified from lifting that attempt because he was not on the platform within the allotted time. In addition, there were spectators and well-wishers that needed to be kept at bay during the warm-up procedure. Each man needed to remain psyched, centered and concentrated; a casual backslap or civilian intrusion at the wrong moment could shatter a carefully constructed psyche. It was intimidating and invigorating all at the same time…I would experience pure fear before every attempt; this was inevitably followed by ecstatic elation after some amazing lift.

These guys nearly always made their lifts and they were spectacular to watch, truly electrifying. They routinely shattered world records, one after another, and did so with predictable regularity. I was the crew chief when each of these hall-of-fame men achieved their respective best all-time power performances. Doug was the first man to total 2400 pounds twice and was by far the lightest ever to hit 2400 at the time—until his partner, Ed Coan, cracked 2400 weighing a mere 219 pounds, a few years later. Chaillet was walking drama: with his blunderbuss deadlift he would usually end up the last man left to deadlift, the man who can and did snatch victory from the jaws of defeat repeatedly. He was the definition of nerve wracking.

Then Doug was gone. He quit powerlifting at the absolute zenith of his career. He simply walked away. He had won national and world championships, he had set numerous world records and to continue onward would be mere repetition, improving upon that which he had already accomplished. He turned his thoughts towards making a living and decided to enter the lucrative yet intensely competitive world of professional wrestling. He was accepted immediately and worked his way through the national and international circuit until he was summoned to the highest level of pro wrestling ranks: the WWF. His lack of flamboyance prevented him from becoming a comic-book superstar, yet his amazing athletic ability assured him a place at the table.

In a dreadful dose of Shakespearian irony, yet another horrid auto accident ended his athletic career. A van full of professional wrestlers were driving from one show to another when the driver fell asleep and drove off the road, plunging into a ravine deep in the Canadian wilderness. Doug’s body was shattered yet again. Auto tragedy commenced his iron journey decades before and decades later another auto tragedy ended it; a gruesome set of chronological bookends denoting the beginnings and ending of an amazingly versatile athlete’s amazing athletic career.

Both Doug Furnas and Ed Coan followed a similar training template: we list their collaborative protocol in the section on Coan.

The Greatest Powerlifter Of All Time…

Without a doubt the greatest athlete I’ve ever had the pleasure of working with is Ed Coan. Incredible Eddy is the Jim Brown/Michael Jordan/Muhammad Ali of powerlifting and his exploits are simply astounding when viewed from any athletic angle, be it peak performances or longevity.

Coan’s friend and compatriot, Doug Furnas, was a powerlifting comet: a man who tore through our sport after rodeo, after big time college and pro football and before pro wrestling. Powerlifting, for Doug, was just another whistle stop, an athletic interlude before commencing his decade long journey as a professional wrestler. Doug passed through the strength universe for a few brief years, leaving an indelible mark, before exiting our sphere and heading onto other athletic worlds to conquer.

Ed landed on planet power in 1981 and as this is being written, Incredible Ed has not been beaten in head to head competition since July of 1983 when he took second place at the National Championships to the power dominator of the previous decade, Mike Bridges. When Ed took second place to Mike, in their one and only meeting, it was symbolic: a handing off of the strength torch from the greatest lifter of the 70’s and 80’s to the greatest lifter from that point forward. It was Bridge’s last competition and marked the start of Coan’s utter and complete domination, a reign that is unmatched in any sport.

It is actually difficult to come up with appropriate frame of reference when attempting to relate to outsiders what a phenomenon Ed Coan actually is. In my book on Ed, Coan: The Man, The Myth, The Method, I made some mathematical analogies that bear repeating. At one point in time, 1991, Ed Coan was mathematically 14.5% better than the rest of the world’s top powerlifters in the 220 pound class. The second best 220 pound World Total was 2,100 pounds; a great total considering that the inflationary gear and equipment “revolution” had not hit powerlifting. The Monolift had yet to be invented and bench shirts of the time added 30-40 pounds to a lifter’s bench press, not 40% to 60% to the lift.

To duplicate Coan’s degree of separation from the rest of the field, a sprinter would need to shatter Asafa Powell’s current 100 meter yard dash record of 9.77 seconds by posting an 8.35 time. Michael Johnson’s current 200 meter World Record of 19.32 seconds would have to be bettered with a 16.52 time. The Cuban Sotomayer’s World High Jump Record of 8’ ¼” would require someone to leap 9’2” and Randy Barnes’ 75’10” World Record in the shot put would need to be blasted to smithereens by someone tossing the 16 pound iron ball 86 feet. That was how far in front of the rest of the strength world Ed Coan was at one marvelous point in time.

Insofar as his longevity: consider the fact that he is riding a 24 year unbeaten streak. I will repeat an earlier analogy: imagine if the 154 pound boxer Ray Leonard fought and defeated every ranking heavyweight contender to miraculously secure the Heavyweight Championship of the World in 1983. Now further suppose that Ray remained a 154 pound fighter and fought for the next 24 years and never lost a single bout. That is the greatness of Incredible Eddy Coan.

Irish Ed is no genetic freak. It would be too cheap and too easy to write off his accomplishments as the result of some sort of accident on the part of nature. Ed is an extremely intelligent and conservative individual who was methodical yet innovative. To those who knew him, Coan was regimented and steadfast. He had an amazing competitive psyche that was so fierce it was frightening—but it wasn’t outward and demonstrative. You had to be fairly close in order to appreciate his internal fire. They say “the eyes are the windows into a man’s soul” and Ed’s eyes could burn holes in wooden walls and start fires prior to a world record attempt. If you stood within three feet of him prior to a big attempt, he literally generated intense body heat. I repeatedly felt the air temperature around his body rise appreciably prior to a gigantic lift. I suppose this was an outward manifestation of some unique internal psychological process.

“This boy will consign us all to oblivion!”

—Rival upon hearing Mozart for the first time.

“Well that’s bad f___ ing news for the rest of us!”

—Nationally ranked lifter learning Ed was moving into his weight class.

I met Ed Coan and Doug Furnas in the mid-eighties while coaching Mark Chaillet at National and World Championships. Mark was a force to be reckoned with, and like Doug, moved up from the 242 pound class to the 275 pound weight class. I had shattered my leg in 1983 and was effectively finished as a lifter. I morphed into a coach and traveled with Mark and his ample posse to competitions, acting as his coach.

The most memorable powerlifting competitions of all time were the incredible Bacchanalian power festivals Larry Pacifico ran in Dayton. Ed and I ran into each other repeatedly at these meets and I was dumbstruck with his lifting. He was a 181 pound lifter when I first began seeing him lift up close and personal. One year at one of Larry’s meets I was on my way to dinner at the Spaghetti Factory across the street from the Dayton Convention Center. I happened to cross the street as Ed and his crew was headed in the other direction. He waved me down and got right to the point. “Doug (Furnas) had a last minute emergency and cannot make it to the competition—can you coach me at the competition tomorrow?” Of course. I was flabbergasted and flattered.

So began a long association that allowed me to coach and assist Ed in those competitions where he performed the greatest powerlifting exploits of all time. I coached him when he posted his greatest ever totals and when he lifted his heaviest ever individual lifts. It was a heady and remarkable time. Describing those golden days of yore to younger lifters is odd. The modern powerlifter only knows of powerlifting since “The Great Disintegration and Scattering.” When I speak of the heights powerlifting once attained before the splintering, these lifters gaze at me as Dark Ages men would if I were describing Rome before the Huns sacked and burned the city to the ground….

“…Imagine a time in the obscure town of Dayton, Ohio when, for a brief sliver of time, everyone who powerlifted competed in a single federation. Those who attended these unified National and World Championships, run under the direction of power impresario Larry Pacifico and his brother Dick, saw the very best, all lifting together, using the same rules, before sold-out convention center audiences. We honestly believed that mainstream acceptance of powerlifting lay just around the next corner.

Imagine a powerlifting competition where all the top lifters in the country competed in a single place at the same time. Imagine a promotional genius who had the wisdom and foresight to hold championship power competitions in the same town, Dayton, Ohio, at the same time, year after year.

As a result of keeping the competitions consistent, over time an audience, an educated audience, grew to love and anticipate the Powerlifting Championships. Year after year, locals and visitors would descend on Dayton to attend these power extravaganzas. Eventually, thousands of people would fill the Dayton Convention Center. People would actually scalp tickets to see the heavyweight finale.

A packed house would sit in air conditioned comfort and watch the greatest lifters in the World ply their trade in front of strict judges in a competition run with the smooth efficiency of a Swiss Watch. Loud, vocal, bawdy, voracious fans hollered themselves hoarse when favorite lifters strode to the platform. Looking around the packed auditorium, the audience profile would be very similar to the type of crowd that attends the annual Sturgis Motorcycle festival each year. By keeping the competitions in Dayton at the same time each year, people were actually planning vacations around attending the Powerlifting Championships.

Returning champions had their airfare and hotel rooms paid for. Larry sent courtesy buses to the airport to pick up top lifters and whisk them back to the luxury hotel that adjoined the Convention Center, connected by a skyway. Each year Larry and Dick layered on another new and exciting twist or wrinkle. At its apogee, Larry flew in Klaus, the funky blind organ player from Germany, and between lifts or in dead spots, Klaus would get the crowd going by playing wild dance music.

Larry had a buffet steam table set up in the auditorium, 100 feet from the lifting, audience members could stroll over from their seats, purchase a hot meat loaf platter, perhaps some roast turkey with mashed potatoes, salads, pies, cakes, vegetables and (drum roll) a bottle of beer for a buck! Then walk back to their seat in time to see Hatfield squat 880 at 220 or Cash pull 832 to beat Fred and Larry. How about seeing Jacoby battle Ladiner? Back and forth these two battled, the lead changed hands something like six times. Joe pulled the winning deadlift of 800 only to be turned down in a 2 to 1 decision! Those were indeed the days.