The Jeffries Barn on the corner of Buena Vista Street and Victory Boulevard, 1940s. The site of many a fine bout. Collection of Michael B. McDaniel .

4

NOTABLE BURBANK PLACES

Burbank is a jurisdiction of 17.379 square miles. Founded in 1887, it is now 129 years old. That being the case, there are indeed a number of interesting Burbank places. But, often with cities Burbank’s size, you have to do some digging to discover where the interest lies. Some of these places are indeed lost, some of them are still with us and one of them has been moved to Buena Park, California.

JEFFRIES BARN

James J. Jeffries was considered one of the great heavyweight boxers of his era. He owned Burbank property on the corner of West Victory Boulevard and North Buena Vista Street. On that property stood the Jeffries Barn, where Thursday night boxing matches were held from 1931 until Jeffries’s death in 1953. It is interesting to note that John Garfield’s big boxing scene in the Dead End Kids film They Made Me a Criminal (1939) was filmed in the Jeffries Barn. After Jeffries’s death the barn was dismantled and moved to the Knott’s Berry Farm amusement park in Orange County, where it still stands as the Wilderness Dance Hall. A Ralph’s grocery store parking lot occupies the barn’s original location. The land for the Jeffries home, across North Buena Vista Street, was one of Burbank’s many vacant lots until 1976, when the Landmark Center shopping plaza was built on the site.

Jeffries gradually sold parts of his ranch, until only his home and barn were left when he died on March 3, 1953. The barn was moved to make room for a labor union building that was near the site. The home deteriorated after Jeffries died and was torn down.

The Jeffries Barn on the corner of Buena Vista Street and Victory Boulevard, 1940s. The site of many a fine bout. Collection of Michael B. McDaniel .

BURBANK BUILDING

Without a doubt the most striking edifice of Burbank’s earliest days is the Burbank Building on the corner of San Fernando Road and Olive Avenue, with its distinctive circular turret that resembles a medieval Russian helmet. Built prior to 1888, it still stands—minus the odd roof feature, which was deemed structurally unsafe and removed after an earthquake. The building was originally planned as a bank, but the Burbank Post Office was, for a time, located on the ground level. The city fathers met upstairs to conduct business, and a wooden sidewalk ran in front. A 1967 Burbank history by the Burbank Unified School District gives this charming note: “When the boardwalk was torn up in 1911, the children skipped school at the ten o’clock recess to go down to look for money which they had heard was under the sidewalk. They had to stay after school to make up the time.”

The Burbank Building, 1890s. Why are there raffish young men on church pews blocking San Fernando Road? We don’t know. Burbank Historical Society .

THE DIP AT THE FIVE POINTS

If you want to start a long conversational thread in any Burbank-related Facebook group, just introduce the subject of one of Burbank’s most fondly remembered greasy-spoon diners, The Dip. It stood as a landmark at a well-known intersection in town, where North and West Victory Boulevards, North Victory Place and West Burbank Boulevard met at the southwest end of the Burbank Boulevard Bridge—the “Five Points.” The electric sign was memorable: it featured a leering neon cook with lightbulb eyes gesturing grandly at a giant hamburger. But the dish that defined the place was the dipped pastrami sandwiches. In the early 1970s, when Wes Clark patronized The Dip daily on the way home from school, the business was run by the brother-and-sister team of Paul Rosen and Gail Ptack. Gail, the wife of a Burbank policeman, enchanted customers with the graceful way she moved from station to station behind the counter. She was, after all, a trained ballet dancer. Sadly, Paul and Gail died some years ago. Burbanker Nickolas Carreon remembers: “At five points—the most dangerous intersection on the planet—there was a hand-made sign in the median in the middle of two-way traffic on Victory Boulevard that read: ‘Left Turn OK For The Dip.’ I don’t suppose we’ll ever know how many people lost life and limb crossing oncoming traffic from multiple directions in an attempt to get a pastrami sandwich.” As Gail’s husband was a cop, the sign must have been okay. Right?

The famous Dip at Burbank’s Five Points (where North Victory Place, North and West Victory Boulevard and West Burbank Boulevard all met before the realignment), December 13, 1972. Collection of Michael B. McDaniel .

THE OWL AND THE TURKEYS : TURKEY CROSSING

Turkey Crossing is the traditional name for the bleak industrial spot where San Fernando Road intersects the railroad tracks in Burbank, but there are very few Burbankers who know why it was called this; it is truly lost history. 24 A Los Angeles Times story from December 20, 1899, tells the tale: On December 18, a thirty-eight-year-old rancher named Daniel Curtis was making the fifty-five-mile trip to Los Angeles with a wagon full of live Christmas turkeys, hoping to sell them in order to make his own family’s Christmas bright. Curtis made it all the way to Burbank and was crossing the tracks when the Owl—the name given to the Southern Pacific passenger train traveling from San Francisco to Los Angeles—hit his wagon amidships, demolishing it. Most of the turkeys were killed (some escaped), as were the two horses, and Curtis himself was seriously injured. The engineer of the Owl, seeing the damage that the train had wrought, reversed the train, picked up the stricken rancher and brought him to Los Angeles for medical attention. His right thigh was broken in two places, and two of his ribs were fractured.

Curtis mended and returned home. In a February 16, 1925 follow-up article in the Times , he recounted his accident and the reason for the now common name for the site. Did he not see or hear the train coming? No. Trees and bushes growing near the track hid the train from view, and the wind was from the wrong direction to hear the locomotive. His brush with death was indeed close: Curtis recounted that the springed seat of his wagon flipped him twenty feet into the air, where he came down near the tracks between the tender of the engine and the first coach. Fortunately he had the presence of mind to see the steps of the coaches whizzing by over his head and did not attempt to stand until the Owl had passed.

Turkey Crossing appears in this photograph from July 17, 1942. It’s at left, where the cars cross the railroad tracks. Note the interesting sign: “Street closed to traffic by order of the U.S. Army!” Burbank Historical Society .

Mike McDaniel shows conclusively where Turkey Crossing is located. (His sign says, “This is Turkey Crossing.”) This area, currently undergoing great change as a result of freeway improvements, will be harder to place in the future. Erin McDaniel .

As is often the case with accidents, legal action followed. Curtis sued the Southern Pacific Railroad for damages and even retained a former U.S. senator as his attorney. The suit took years to resolve and only resulted in nominal damages being recovered. But it’s a great story!

The Turkey Crossing location was the site of another accident, this time in December 1920. In a December 31, 1920 Los Angeles Times article partially entitled “Keeper of Booze Warehouse Injured,” the story is told of John Tressider, the keeper of a general bonded warehouse (a euphemism for the Prohibition-era liquor cabinet in Los Angeles). Failing to see the sneaky and elusive Owl, his car was struck at the intersection, coincidentally on Tressider’s eighteenth wedding anniversary. The auto was demolished, and Tressider and his two passengers were seriously injured. The authors could not find a follow-up article to discover if all three passengers survived their injuries, but the article concluded with a statement that Tressider’s set of keys to the government liquor warehouse—the only ones—were returned when the revenue collector dispatched a deputy to pick them up at the hospital. They took no chances with something that important falling into the wrong hands, and there would be no riotous parties in Burbank that night.

Perhaps not surprisingly, a March 9, 1924 Los Angeles Times article describes the “Turkey Neck Curve” as “obnoxious” and in need of straightening. (The pictorial name suggests that the original meaning of the name as a place where turkeys were once hit was becoming lost.) The straightening never happened.

Fast-forward to 2014, when, as a result of traffic-improvement work by Caltrans, the historic Turkey Crossing site is apparently scheduled to be graded out of existence. As of this writing (spring of 2016), the site is a mess, and traffic around the construction is miserable.

The way you find the historic site is to line up a position on the tracks so that you can see down San Fernando Road. In other words, continue the line of the road to where it intersects the tracks—that’s the 1899 Rancher Curtis Turkey Crossing site. But this is dangerous, and we don’t recommend it!

HOTSIE ALLEY

This is a site on West Jeffries Avenue between North Pepper Street and North Hollywood Way, fondly remembered by Wes Clark as he walked home from Luther Burbank Junior High School as a thirteen-year-old in 1969. One of Burbank’s countless alleys, suspicious-looking teens used to congregate there after school. If stared at, the girls radiating defiance with blue eyeliner, too much makeup, ratted hair, provocative blouses and cigarettes held between fingers would loudly demand, “Are you hassling me? Ya wanna hassle ?”

Hotsie Alley, where fearsomely defiant teenage girls gathered in the 1960s. Wes Clark .

“Hotsie?” This is what Wes Clark’s mother (born in 1921) called the drugs she was certain were being distributed at the site. But what self-respecting teen in the late 1960s would ever call a drug a “hotsie?”

CITY HALL AND THE BALLIN MURALS

Groundbreaking for the current city hall building took place on February 17, 1941. The edifice was designed by architects William Allen and W. George Lutzi, and the project was funded by the Federal Works Agency, Works Project Administration (WPA). It was completed in 1943 at a total cost of $409,000. On our website Burbankia, pictures of city hall are as numerous as fleas on a junkyard dog; it seems that the city could not take enough photographs of the place, and it was a constant subject for city photographer Paul E. Wolfe. Old photos turn up all the time. Granted, it is an architecturally striking building, a fine example of Art Deco design. But the authors have always maintained that it’s what’s inside that is especially interesting: the Hugo Ballin mural. Ballin (1879–1956), a muralist, film producer and author, was quite active in the 1930s. He did work for the Los Angeles Times , the Wilshire Boulevard Jewish Temple and the Los Angeles City Hall chambers.

City hall nearing the end of construction in 1942/1943. City of Burbank .

Hugo Ballin’s Four Freedoms mural in the council chamber of city hall, depicting the themes of a famous January 6, 1941 speech by Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Left to right: Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Religion, Freedom from Want and Freedom from Fear. Wes Clark .

If you’ve ever visited the Griffith Park Observatory in Los Angeles, you are acquainted with Ballin’s work. Look up. Those impressive and striking paintings of Greek gods, the Zodiac and other celestial figures are by Hugo Ballin. But he also designed the impressive mural The Four Freedoms , which can be seen in the Burbank City Council chamber. It refers to basic freedoms identified by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1941: Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Religion, Freedom from Want and Freedom from Fear. It really is impressive. The next time you’re in the building, ask to see it.

What about city hall can be considered “lost”? In the early 1960s, before the construction of suitable facilities, it also served as the city jail—the bars and cells are still easily recognizable in the basement on the west side. But where criminals and scofflaws once glumly spent their evenings is now the domain of paperwork, records and other official impedimenta. The city clerk uses the area—now called the Records Center—for storage. Another room in the jail still has the huge iron door that once protected the Burbank police weapons cache. Now the door protects used office supplies for redistribution within the city departments and records due to be shredded. Of additional historical interest is that this room holds a collection of all the portraits of the Burbank mayors that hung in the council chamber during their tenure. A final item of interest in the old jail is the wall where police department employees took accused persons’ photographs and formed lineups for identification by witnesses.

The jail in the basement of Burbank City Hall, 1950s. Rumor is, the ghost of convicted murderer Barbara Graham haunts this place. Over the years her image has appeared to various city and custodial workers. That’s what we’re told, folks! Burbank Historical Society .

Also now lost is the original courtroom that was above the jail on the main floor of city hall, now the city attorney’s offices. The original portrait of “Justice” that hung in the court is in the main entrance to the attorney’s office. The stairs by which perps were led from the basement up to the courtroom to have the book thrown at them remain intact.

The basement of the building is also the domain of Mike McDaniel, who works in the print shop there.

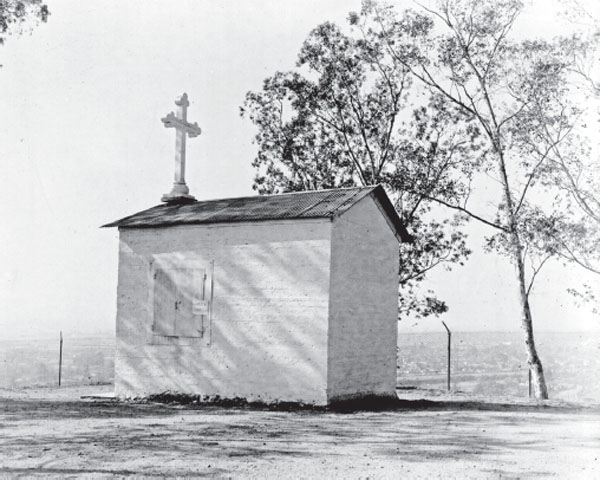

CABRINI CHAPEL

It used to be a small white structure on the Burbank side of the Verdugo Hills, seen by all in the valley—a spiritual landmark for fifty-six years. Cabrini Chapel was ordered built in 1917 by Saint Francesa Saveria Cabrini (1815–1917), aka Mother Cabrini. She was the first American citizen to be canonized a saint by the Roman Catholic Church, in 1946. The site used to be the focal point for devotional processions and pilgrimages sponsored by the Italian Catholic Federation, and in covering the news of such processions, the hard-bitten and worldwise newsmen of the Los Angeles Times also called the site charmed, as it somehow escaped damage during the occasional brushfires in the area.

The humble little white chapel couldn’t evade progress, population and the march of time, however, and as the building of the Cabrini Villas housing development in the early 1970s threatened the site, the building was moved to the grounds of St. Francis Xavier School in Burbank, at 3801 Scott Road. The authors are happy to report that the housing developers moved the building at their own expense and that the chapel was restored and can today be seen on the grounds of the school, where a library has been added to it. A pretty mosaic of Mother Cabrini was subsequently placed above the door.

Undated image of Mother Cabrini’s little chapel on the Verdugo Hills, a landmark for miles around. Collection of Michael B. McDaniel .

VERDUGO FAULT

Ever since the authors read that the Verdugo Fault, which runs more or less along the Burbank side of the Verdugo Hills, is visible from the cul-de-sac at Churchs Court off North Sunset Canyon Drive, we’ve wanted to highlight this relatively unknown spot. If you go there you can see where the land and the rocks lift a bit; when the celebrated Southern California Big One finally hits, this will perhaps be new shoreline and increase immeasurably in property value—of scant interest to the people living there, as their homes will be in the Pacific Ocean.

The Verdugo Fault at the end of Churchs Court. Will this be beachfront property in the future? Wes Clark .

PNEUMONIA ALLEY

With the disappearance of the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation came the disappearance of a location in the plant known to employees as Pneumonia Alley. It was one of the interesting aspects of working in Lockheed’s B-1 plant. Pneumonia Alley was a breezeway formed by two closely adjacent buildings that shared a common roof at some point in its life—at least, that’s how it seemed. The name came from the fact that both ends were open, and a constant breeze flowed through the place. It was pleasant in the summer but foul and objectionable on very cold days. No less a photographer than Ansel Adams once took a photograph showing it from one exterior end.

Wes Clark used to work at Lockheed in plant maintenance, which meant that he was required to shuttle around B-1 in a small Cushman scooter, picking up trash, moving things and so on. Driving through Pneumonia Alley gave the distinct impression that one was not in a plant where cuttingedge airplanes were built but rather a Disney dark-house ride, specifically the Snow White ride, where the dwarves were working in the mine and singing “Heigh Ho.” Pneumonia Alley was always rather poorly lit. Looking to the left and the right while driving through it, one could see the various cutting machines used to manufacture parts, with machinists walking around, tending big pieces of aluminum and pushing what looked like mine cars. It was actually rather picturesque in an industrial fashion.

BURBANK VILLA/THE SANTA ROSA HOTEL /DOWNTOWN POST OFFICE

The Santa Rosa Hotel, originally the Burbank Villa, was built in 1887 by none other than Dr. David Burbank, from whom the city gets its name. It was a focal point for social celebrations by Burbankers and hosted parties and weddings. By 1927 it had been torn down, and in 1938 the site was used for a new post office, which still stands at 125 East Olive Avenue and is on the National Register of Historic Places. Lost lore? One of the Santa Rosa Hotel’s most faithful early guests was Hollywood star Billie Burke—none other than Glinda the Good Witch of the North in The Wizard of Oz (1939).

THE LOVEJOY CASTLE

If one drives on East Providencia Avenue past South Sunset Canyon Drive to the end of the street, an interesting sight can be seen against the Verdugo Hills—a white, stucco-covered tower, complete with a crenellated roofline. It looks impressive, almost like a castle. What is this place? Brian Schneider, whose family owns the property, told Wes Clark in a June 8, 2012 e-mail message:

The Lovejoy Castle, atop East Providencia Avenue. The warlord living therein can station archers on the roof! Wes Clark .

It is a Moorish castle built in 1926 by a man named Lovejoy, who was a railroad tycoon and the son of a Confederate who owned the Lovejoy plantation in Atlanta, now known as the Crawford-Talmadge House. The property is on eleven acres and was purchased by Lovejoy. Over the years it was used as an orphanage and a sanitarium. Lovejoy went bankrupt in 1929, and the purchasers felt sorry for him, so they took a shack on the property, moved it to a corner and gave it to him. His relatives owned Lovejoy’s Antiques in Toluca Lake for years. One cool thing about it is that for some reason, the property has been adopted by a herd of deer. There are usually between five and fifteen deer just hanging around on it, under trees in the front lawn or in what we call “the meadow” below the house. In the 1980s my parents rented the house to Olivia Newton-John’s production company. She had her musicians stay there when they were in town and I believe they filmed a music video there. At least that’s what they said. But I never saw it .

Fun fact: “Burbank” is both a common place-name in English-speaking countries and a fairly common surname. It is of English origin and means “lives on the castle’s hill.” Sounds like the Lovejoy property.

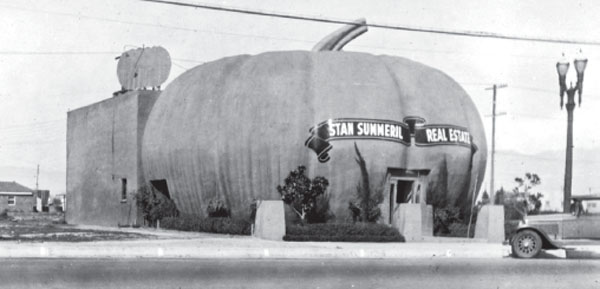

THE PUMPKIN BUILDING

As has been endlessly noted, Southern California is a different kind of place. The architecture can be odd, too, and for at least thirty years a building in the shape of a giant pumpkin stood on 3611 Magnolia Boulevard. It was known variously as the Pumpkin Inn (“ballroom dance and prizes!”), the Pumpkin Palace, the Studio Club (one of the owners was Ed “Strangler” Lewis, a wrestler), the Valley Gospel Center, Stan Summeril Real Estate and Magnolia Park Hardware (“Fine Old Colony paints”). In 1938, a Los Angeles Times columnist noted:

An extraordinary edifice, shaped like a pumpkin, is yours for the seeing in Magnolia Park, a suburb. Upon it are painted three legends. One reads, “The World’s Largest Pumpkin,” another, “Valley Gospel Center,” and the third, “For Sale by Owner.”

It appears that the building’s distinctiveness did not necessarily endear it to owners. Another 1938 article noted that there was an opening-night fire, which was put out without much fuss. But it cast an ill omen. The owner later gave up the business, stating, “Heck, I ought to have had more sense than to fool around with a pumpkin!”

Burbank’s celebrated Pumpkin Building on Magnolia Boulevard, seen here in its incarnation as a real estate business, 1930s. Collection of Michael B. McDaniel .

By 1956 the Los Angeles Times reported that a “hard luck gal” named Mae Williams bought a part ownership in the Pumpkin; later on in the year she began wearing her earrings on the top of her head.

MUSHROOMS EATERY

The Pumpkin Building wasn’t alone; in the late 1920s at 3500 West Olive Avenue stood a walkup eatery called The Mushrooms—yes, it was built in the shape of a giant fungus. We have no other information about it, save that a sign in the front said (perhaps ominously), “Won’t Be Long Now.”

THE GOLDEN MALL

You have to give the city planners credit. The Burbank Golden Mall was a bold exercise in forward thinking: six city blocks long, it incorporated futuristic, hexagonal designs with restroom facilities, fountains and pedestrian-only access to the stores along San Fernando Road. No dirty, noisy cars would ruin the Burbank shopping experience. The promotional text that Burbank supplied said it all: “A six-block, traffic-free ‘Golden’ Mall has been scheduled for construction during 1967. The area will encompass the present downtown Burbank on San Fernando Road from Tujunga Avenue to San Jose Avenue. This undertaking has been intelligently designed for pleasurable shopping and browsing in a relaxed and attractive atmosphere.”

Jan Chronert, the Golden Girl, and the mayor of Burbank at the groundbreaking for the Golden Mall on May 6, 1967. City of Burbank .

The construction of the Golden Mall on San Fernando Road, circa 1967. City of Burbank .

It didn’t take long, however, for the dream to sour. Shoppers complained about having to park far away from the stores they wanted to visit, rather than right in front, as they were used to doing in the pre-Golden days. Shoppers increasingly drove to Glendale to buy. Also, the quality of the stores began to decline, and then they failed entirely. Bur-Cal (a store name that deserves to be revived), Thrifty Drug Store, Sav-On, Newberry Co., Woolworth’s, J.C. Penney, good jewelers and banks—they disappeared one by one. Shabby used bookstores began to open in the large spaces where, previously, impressive department stores could be found. Even the water in the fountains became dirty, when there was water in them at all. The worst became apparent in the late 1970s, when the city opened a job-assistance office across from Ed’s Town Shoppe; shabby-looking men ambling around the office was hardly the sort of thing one expected from the futurists. Conceding defeat, in 1989 the City of Burbank removed the mall entirely and once again opened up San Fernando Road to vehicular traffic.

The authors are happy to report that business is once again thriving along a revived San Fernando Road.

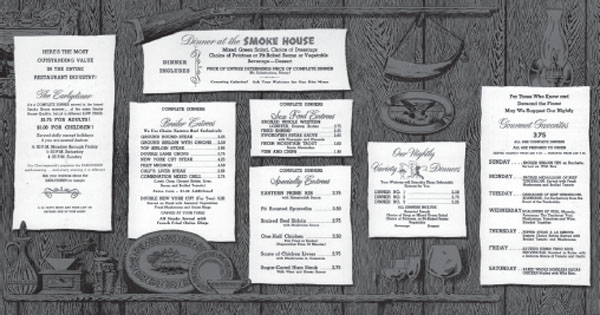

THE SMOKE HOUSE RESTAURANT

Established in 1946 by two Lockheed engineers, the Smoke House is beloved by Burbankers for its garlic bread (you must really try it when in town). After a start elsewhere in Burbank, in 1948 the business moved to its present site, Danny Kaye’s planned but never opened Red Coach Inn. The restaurant benefited from its location on the banks of the Los Angeles River, across the street from the Warner Bros. Studios; Kaye had chosen well. Bing Crosby, Bob Hope, Judy Garland, Errol Flynn, Humphrey Bogart, Cary Grant, Milton Berle, Robert Redford and anyone who was on staff or onscreen at the studios during Warner’s “golden” (and present) years ate there. In fact, according to the Smoke House’s website, George Clooney was such a fan of the place that he named his production company Smokehouse Pictures, Inc.

A Smoke House menu, circa 1960. Look at those prices! The garlic bread is, of course, legendary. Collection of Michael B. McDaniel .

The Smoke House has impeccable Burbank credentials in addition to the garlic bread: George Schlatter, the producer of Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In , cast Gary Owens—the man who popularized the phrase “beautiful downtown Burbank”—on the spot upon hearing him say, “My, the acoustics are good in here!” in the men’s room in his impressive announcer’s voice.

(Fun fact: Johnny Carson was not the only entertainment industry figure who enjoyed skewering Burbank. George Schlatter did as well. Some of his zingers: “Burbank is a lot like Paris—with chickens.” “Beautiful downtown Burbank is nestled on the banks of the Los Angeles River: a cement canal.” “If you’ve seen Tijuana, you’ll love Burbank.”)

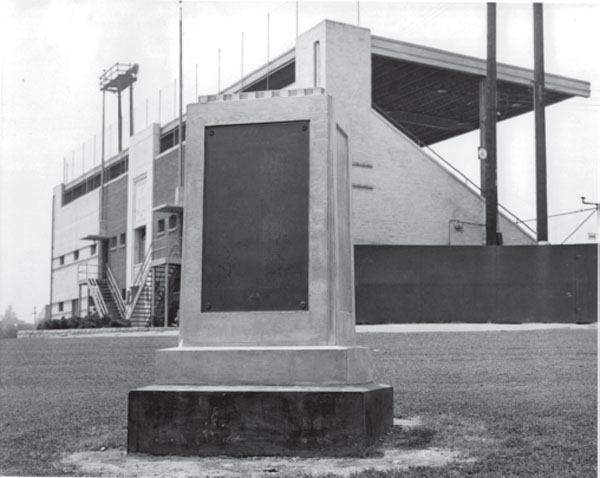

THE BURBANK –ST . LOUIS CONNECTION

At the intersection of West Olive Avenue and South Virginia Avenue is a modern athletic facility called the Olive Recreation Center; it features play areas for children and no less than four baseball fields. On the same site once stood Olive Memorial Stadium, built in 1947 and dedicated to the memory of American war veterans. It was deemed unsafe and demolished in 1995. Once, Burbankers were proud that it was the spring training site of Major League Baseball’s St. Louis Browns. But the history of the Browns at Burbank is lost.

Olive Avenue Recreation Center Stadium, almost completed in 1946. Collection of Michael B. McDaniel .

A Los Angeles Times article, “Burbank’s Big Leagues: At Olive Memorial Stadium, Hapless St. Louis Browns Got Some Respect,” from October 2, 1994, by Vivien Lou Chen describes the importance of the place:

Burbank, where the feckless baseball team conducted spring training from 1949 to 1952 at Olive Memorial Stadium. Hundreds of spectators, among them Bing Crosby, Bob Hope, Dinah Shore and Nat King Cole, eagerly piled into the stadium to see the likes of pitcher Satchel Paige and Manager Rogers Hornsby in 1952, despite the fact that the Browns were arguably the worst team to ever play the game .

“We were not all that good a team, but Burbank was just happy to have a major league team and the guys we had playing were just happy to be in the major leagues,” said former Browns infielder John Beradino, now a television actor who plays the chief of staff on General Hospital. Forerunners of the Baltimore Orioles, the Browns will always be remembered by baseball buffs as the team that sent a midget to bat, used a one-armed outfielder and once finished 64 1/2 games out of first place. The Browns’ proudest moment—the 1944 World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals—ended in embarrassing defeat, with a team batting average of .183 .

THE WONDER YEARS HOUSE

The authors are fans of this ABC television series, which ran from 1988 to 1993, for a number of reasons: (1) The protagonist, Kevin Arnold (played by Fred Savage), was described as being sixteen in 1972, which means that he was born in the same year as the authors and experienced the 1960s and 1970s at the same ages we did; (2) The production company used Mike McDaniel’s junior high school in Burbank, John Muir, for filming. In fact, Kevin’s locker is just five spaces away from Mike’s and appeared in the interior shots on the show; 25 (3) The teleplays are easily as good as anything that was ever on television; and (4) The home shown in the series as being that of the Arnold family is in Burbank, at 516 North University Avenue.

PORTAL OF THE FOLDED WINGS , SHRINE TO AVIATION (AKA DOME OF THE AVIATOR )

Burbank has its very own nifty little aviation industry spots in the shade of this venerable and artistic structure, located in a cemetery (Pierce Brothers Valhalla Memorial Park and Mortuary, 10621 Victory Boulevard), within sound of the planes taking off and landing at the nearby airport. By visiting and looking at the various plaques, you can learn a thing or two about aviators in the early days of flight. The structure, built in 1924, was originally the entrance to the cemetery, but that was changed so that the park entrance appeared on the much more heavily traveled Victory Boulevard, a main east–west route in the San Fernando Valley. Fourteen of the United States’ most famous and accomplished aviators are buried within or near the structure; 26 Charles E. Taylor, the man who hand-built the first aircraft engine used by the Wright brothers, is buried here.

A modern image of the Portal of the Folded Wings. Wes Clark .

BOB ’S BIG BOY

The Toluca Lake Bob’s on 4211 Riverside Drive was built in 1948 and is the oldest remaining Bob’s Big Boy restaurant in the United States. It has long been a gathering place for car enthusiasts on Friday nights. The well-attended, informal car show is truly something to see and is so reflective of the Southern California culture: swaying palm trees, a western sunset, warm weather and 1956 Chevys. According to the restaurant chain, this particular location also has a claim to Beatlemania. In August 1965, while on tour in the United States, John, Paul, George and Ringo, reportedly seeking an authentic American diner experience, ate there. A plaque is mounted on the wall near the booth where the Fab Four allegedly sat. It gets stolen from time to time, but Bob’s management always replaces it. However, it seems odd that, as fully documented as the Beatles were in that mad summer, there are no photographs of the visit. Their biographer, Barry Miles, described them as being trapped in their house during the tour, a result of fans watching their every move. But it’s a good story, and it sells burgers.

THE MOST ACCIDENT -PRONE HOUSE IN THE COUNTY

Called that by the reporters of the Los Angeles Times , the house sits at a Burbank “T” where North Buena Vista and Vanowen Streets intersect, nestled in a depression behind protective guard rails and flashing red lights. But that doesn’t stop motorists from flying into the property of the Espinoza family—and this has been going on for five decades. The problem, according to reporters in articles from 1975 to 1985, is that neglectful, intoxicated or even sleeping motorists fail to realize that Vanowen Street ends—drivers must turn right or left onto Buena Vista Street—and they plow into the property’s trees, garage, kitchen, front yard and porch. (The count in 1975 was seven garage doors, several automobiles, two retaining walls and dozens of shrubs.) The site has seen at least five traffic deaths and an untold number of nonfatal crashes.

When Wes Clark was a child, he noted the many accidents that seemed to happen there (the Clark home was less than a half mile away from where the family lived) and asked his father why this was. “Lockheed drunks,” was the laconic reply.

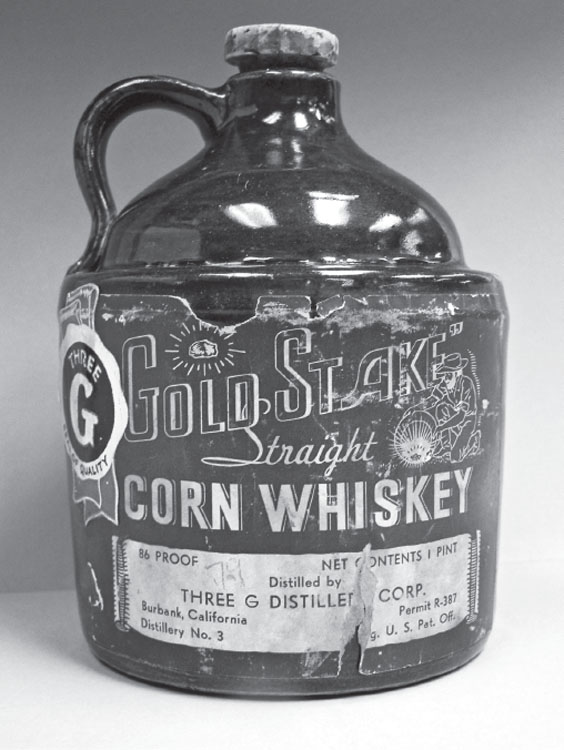

THE THREE G DISTILLERY

As noted earlier, Burbank used to have many vineyards. It also had a nationally advertised whiskey distillery. McDaniel family lore was that Burbank was once also known as “Beer-tank,” in recognition of the city’s output of alcoholic beverages. The Three G whiskey distillery (producers of Rock and Rye, “conceded the world’s finest all-around drink”) was located just north of San Fernando Road. In order to gain more floor space to design and produce the famous P-38 Lightning, the distillery was purchased by Lockheed in June 1939. Lockheed workers vividly recall coming to work on Monday mornings, the factory redolent of the scent of bonded whiskey in oak barrels in the converted facility. The distillery turned aircraft factory is gone, as is Lockheed. It only turns up in Three G Whiskey bottles or advertisements sold on eBay.

Gold Stake Corn Whiskey, a proud product of the Three G Distillery in Burbank. Collection of Michael B. McDaniel .

WHERE THE POSTMAN ALWAYS RANG TWICE

It’s not commemorated, but it’s true: the unassuming home on 616 South Bel Aire Drive was once the residence of pulp novelist James M. Cain (1892–1977). He wrote The Postman Always Rings Twice while renting this property for forty-five dollars a month in 1934. In 1949 his book was turned into a famous film noir starring John Garfield and Lana Turner. Cain also wrote the noir classics Double Indemnity and Mildred Pierce .

Cain found Burbank’s Depression-era hoboes inspiring. In Packed and Loaded: Conversations with James M. Cain , he writes:

Take a book of mine that was about something somewhat off beat, The Moth, which was about a young, ex-football player and singer who I put through the depression of the early 1930s. Well, I came to that book honest. I was living in Burbank briefly at the time and I’d drive out past Warner Brothers’ Studio and be held up to enter the Town of Burbank. A freight train parked on the side there. This would happen quite a few times. The freight would seem to arrive right about the same time. Maybe I’d been in Hollywood to some picture show or something. This would be my [sic] 11:15 every night and silhouetted against the dark of Burbank itself would be these heads on the top of these freight cars. Not just two or three of them, or three or four dozen—three or four hundred of ’em! And it seemed so terrible a thing that these boys—most of them just boys—couldn’t stay home anymore. Had no place to go but the top of this horrible freight car…”

The little home on 616 South Bel Aire Drive that James M. Cain rented in the 1930s. Here, Cain developed the plot by Frank and Cora to murder husband Nick in The Postman Always Rings Twice. Wes Clark .

There are probably other notable places involving lost lore in Burbank; the more the authors do research, the more we find out about these. It seems that just when we think we have the last word in odd, quirky or unusual Burbank things, something else turns up—fodder for a future book or website updates, perhaps.

The McClure Winery. Burbank used to be this rural. The little Cabrini Chapel is seen atop the hill. Burbank Historical Society .