Fawkes’s Folly, aka the Aerial Swallow, Burbank’s famous monorail, circa 1911. Burbank Historical Society .

6

BURBANK INVENTORS

Is Burbank, California, a hotbed of invention? Using the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s online search tool returns 2,337 patents on a search for “Burbank” in the inventor city field. A quick search returns 6,872 patents for “Lockheed” as a search term. We are uncertain how many of these date before the 1990s, when Lockheed left Burbank, but the answer is almost certainly thousands.

We begin with historical Burbank’s most celebrated and, it must be admitted, quaint inventions and inventor.

FAWKES ’S FOLLY AND JOSEPH WESLEY FAWKES

Let us consider the invention before the inventor.

Most accounts of Burbank’s famous “Aerial Swallow” (as inventor J.W. Fawkes called it) describe his innovative transportation scheme as a monorail, but this is only accurate in a loose sense. The system involved a passenger transportation vehicle, driven by a huge fan (an enormous potential safety concern) suspended from what appears to be a tube or pipe. U.S. Patent number 1,020,010 (granted May 28, 1912) describes an “aerial trolley” suspended from a “trolley line.” There was no rail. However, patent number 1,051,093 (granted January 21, 1913) describes a “strong wire or angle bar”; Fawkes’s creation was probably undergoing refinement. 32 Without belaboring the technical matters, the occasional claim to Fawkes’s Aerial Swallow being “America’s First Monorail” needs some elaboration or, perhaps, an asterisk. The aerial trolley car was tested on a six-hundred-foot line on Fawkes’s farm at 110 West Olive Avenue, roughly the area where the Bormann Steel Corporation and a recreational vehicle business are located today.

Fawkes’s Folly, aka the Aerial Swallow, Burbank’s famous monorail, circa 1911. Burbank Historical Society .

You can’t fault Joseph Fawkes for not presenting his invention with a sense of occasion. On July 4, 1911, he opened his farm to the public, hired a musical ensemble (it looks like a jazz trio) and hung streamers and American flags on the Aerial Swallow. Men in bowler hats and women with parasols clustered about as Fawkes presumably made a speech on a platform. People then boarded the system, and the enormous propeller was made to spin. A photograph shows the thing apparently in motion, with somebody running alongside. (But why was he running? The Swallow reportedly had a top speed of three miles per hour—walking pace.)

Fawkes’s idea didn’t take off, mainly because mass-transportation schemes of the day faded in favor of individually owned, gasoline-powered automobiles. And when it came down to actually deciding on a scheme to get people from Burbank to Los Angeles and back, a conventional electric trolley was the chosen solution.

Fawkes’s trolley, abandoned and rusting, was dismantled in the early 1920s, probably when he sold off his property as an industrial tract in 1923.

What sort of man was Joseph W. Fawkes? To answer that question, we proceed to the next section of this chapter.

THE FAWKES FAMILY FOLLIES

You can imagine the glee and anticipation experienced by reporters for the Los Angeles Times whenever news came in about the troubled Fawkes family of Burbank. The fuss began in 1895, when an August 25 piece entitled “Brotherly Love—Conspicuous Its Absence in a Recent Case” describes how Jacob Fawkes and a firm called Cairns & Company vied for a contract to maintain street signs for free. (The value was in the fact that the winner of the contract was able to use the signs for advertising.) The board of public works denied the offer, and it came out that Cairns & Company was an unnamed brother of Jacob Fawkes (Joseph?). The two were described as “deadly enemies anxious to cut out each other’s throats in business.” In addition, one of the brothers claimed to be the inventor of the street sign who then lost the patent when the other brother learned of the invention.

The article concludes with a mention of the Fawkes brothers’ father, Joseph Walker Fawkes (“J.W. Fawkes, Sr.” as styled in the papers), described as the inventor of the famous Fawkes steam plow, which made a fortune for the family.

A subsequent Times article from December 29, 1895, describes the “Fawkes fraternity” having a “social session” in court. J.W. Fawkes Jr. (the Aerial Swallow inventor) initiated a suit against his father, J.W. Fawkes Sr., over some property. (J.W. Sr. is an old man at this time, over seventy-two years of age.) J.W. Jr. is described as being the black sheep of the family, at loggerheads with all the rest save his brother H.B., who served at the time as a deputy constable in town. There is some discussion of J.W. Fawkes’s wife, of whom the rest of the family did not approve. One Fawkes brother offered J.W. twenty-five dollars to tell him where the valid marriage license was issued. An accusation was made, serious in those strict times, that the two were living together. Feelings ran high in Burbank against “Joe” Fawkes, the piece claims. The article ends with the surprising revelation that Joe Fawkes once mixed some sort of “dope” in front of his mother’s window, chanting, “Dynamite blow you up tonight!”

J.W. Fawkes doing some flag-waving at his Burbank–Los Angeles Consolidation booth around 1922. Note the shotgun behind Fawkes’s left elbow. Was he expecting trouble? Burbank Historical Society .

A Times article dated August 9, 1896, describes a search warrant filed by J.W. Sr. against his son J.W. Jr. (henceforth “Joe” for clarity). The issue involved 325 feet of iron water pipe.

The Fawkes family’s annus horribilis seems to have been 1898. A January 29 piece entitled “House Divided Against Itself ” describes how “time and again one member of the family has been dragged into court by the other.” In 1898 Joe Fawkes swore out a warrant for the arrest of his brother H.B. Fawkes for petty larceny involving a load of lumber. Joe also filed a suit in civil proceedings against his brother to have him evicted from the premises and require reimbursement for the destruction of a barn, a hen house and a pig pen.

On March 23, 1898, an over-the-top article entitled “An Infernal Machine” described allegations by J.W. Fawkes Sr. that Joe had deliberately planned to blow up Fawkes Sr. and his wife by means of a bomb placed under the house, connected to a detonator by means of an electric wire. There is also some discussion of property lines and the erection of a shed built spitefully by Joe to be within inches of his father’s house; when the shed was completed, it completely shut out the light in the kitchen so that the mother had to use a candle any time of the day to see. Burbankers familiar with the situation would have none of this, however. One night, they banded together as vigilantes and mounted the structure on skids, hauled it away and burned it!

Getting back to the infernal machine, the Fawkes mother reportedly heard her son say to a carpenter, who was in cahoots, things like, “It must be arranged to blow the old man up first,” “I want to scatter their bones all over the orchard” and “It’ll be hard work to find any of the pieces after this thing explodes.” Murderous, indeed. The Fawkes mother told her husband what was up, and he investigated a second shed placed near his home. He found an object about a foot high, eight inches in diameter and wrapped in paper, with five wires running from it. J.W. Sr. went to the district attorney and had his son and the carpenter arrested and hauled before the justice of the peace. The article ends at this point.

Was it really an explosive device? No. An April 16, 1898 article revealed that the bomb was just sand in a tin can with wires running therefrom, created in an attempt to prevent indignant Burbankers from hauling another structure away. An April 19 article describes the release of Joe and the carpenter on a writ of habeas corpus, and a piece in May describes the carpenter attempting to sue Fawkes Sr. for $10,000 in damages. In June the carpenter swore a complaint against a Fawkes brother, H.B., for perjury in court. Another suit between T.W. Fawkes and H.B. Fawkes is mentioned. Is this getting confusing?

In late November, a Judge Van Dyke attempted to get the Fawkes family members to reconcile and to go home and enjoy Thanksgiving. After a recess, Joe Jr. and Joe Sr. agreed to bury the hatchet and dismiss their suits. But Joe’s brother Howard, not feeling the love, refused to be placated, and his case continued. December 1898 rolled around, and the Times reporters noted that “the drear monotony of surburban life has been relieved, and the courts of the county have been prevented from stagnating by having the Fawkes cases to adjudicate.” In the same month a Solomonic judgement was issued that resulted in a moral victory for Howard Fawkes and a cash settlement for his brother Joe. Has family peace finally settled in?

Apparently. In 1899 Joe Fawkes Jr. and Sr. settled over a matter concerning possession of a home and a barrel of vinegar. (One cannot help but see the vinegar as metaphorical.) But Joseph Fawkes Jr. wasn’t finished with the media, nor were they finished with him.

In a 1922 letter to the Los Angeles Times editor, Fawkes complains about high taxes in Burbank and describes why consolidation with Los Angeles would be beneficial. (In the 1920s he led a failed annexation drive.) 33 Also in 1922, Fawkes wrote a letter to the editor seeking to calm the populace about a rabid dog and about rabies in general. In September he is thrown in the Burbank City Jail for disturbing the peace. In 1925 he pleads innocent to firing a shotgun at some anti-annexation boys who threw red flares on his lawn. The animus might be understandable, as earlier anti-annexation celebrants hanged him in effigy near a bonfire on San Fernando Road; a placard read, “Here lies the body of Consolidation Joe.” In June 1928 J.W. Fawkes Jr. died at age sixty-six.

The last time Joe Fawkes is mentioned in the pages of the Los Angeles Times was on February 10, 1929, in a piece describing how Howard, William and Leslie Fawkes (brothers of the deceased) claimed that Joe’s will was “unnatural” because it didn’t mention them. The three also asserted that the woman he names as sole heir of his $29,000 estate, his wife, Emma, was married as a result of an illegality. The situation never seems to end.

Let us quit there. So, what kind of man was Joseph W. “Joe” Fawkes? The authors must conclude, something of a nut.

MAURICE POIRIER, THE TEN IDEAS PER MINUTE MAN

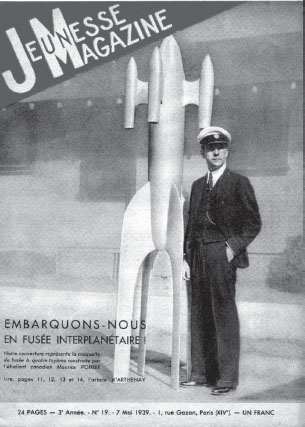

Monsieur Maurice Poirier looked like a movie star, with a boyishly handsome face and smooth dark hair. He always dressed in a well-tailored suit. Sometimes he wore a natty moustache, sometimes a white yachtsman’s cap. An appealing and dapper figure, one can see why the newspapermen and magazine editors liked him and reported on his various inventions. He was apparently of a brilliant turn of mind; a Los Angeles Times reporter called him the “Ten Ideas per Minute Man.”

Maurice Poirier was a French or French-Canadian naturalized American who settled in Burbank at the close of World War I; he resided at 324 East Tujunga Avenue. Sources variously describe him as a watchmaker, jeweler, inventor and, later on, aircraft worker. He was described as working out of a “mountain laboratory” in the “back of Burbank,” where he invented things, dreamed great technological innovations and patented useful devices. (He held at least five patents that we could find.)

Some of his inventions seem quaint, now that technology has passed him by. Or were they prophetic? A 1928 press caption shows him standing with a “radio power plant.” Whether this one-thousand-foot device was meant to power airplanes over a distance or merely direct them is not made clear. In 1929, Modern Mechanics included a photograph of his rocket plane, a standard gasoline-powered craft augmented with rocket motors and eightysix gun barrels; the thrust from the rockets propelled the plane to as much as four hundred miles per hour. In a 1930 photograph from the Cumberland Evening News , Poirier is shown with his assistant Franklin Wallace examining a plane with no fewer than fifteen rocket tubes on the tail. Poirier hopes that such a plane might achieve a speed of six hundred miles per hour. The cover of a 1930 Popular Aviation magazine shows a rocket plane described as able to reach one thousand miles an hour. Clearly, Poirier had a need for speed.

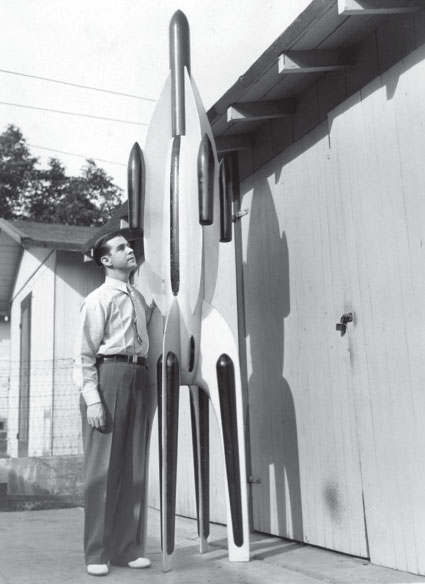

Inventor Maurice Poirier with his futuristic-looking rocket ship in his Burbank backyard, June 26, 1937. Collection of Wes Clark .

Maurice Poirier on the cover of Jeunesse (Youth) Magazine , May 7, 1939. “Let’s board the interplanetary rocket!” says the caption. Jean-Jacques Serra .

Was there anything too audacious for Poirier? A 1939 photograph shows him, hand casually placed in pocket, standing next to a fantastically shaped rocket that would be at home in a 1950s sciencefiction thriller. As war approached, a 1936 piece in Popular Science showed his war rocket that could, it was claimed, rain bullets over a mile-wide area. With one technology, he was on the right track: liquid rocket propellants in place of explosives. In another area, he was all wrong: the ingredients for the liquid propellant were extracted from weeds found only in Europe—Germany, in fact! In other articles, Poirier claims altitude targets, to cross the barrier of Earth’s gravitational pull with a rocket that can exceed 500,000 feet.

Poirier was probably better off with his inventions concerning time and special-purpose clocks and watches. One such watch, developed in 1937, featured a twelve-minute dial to aid in the use of following navigational radio beams. In 1941 his attention was fully focused on the war; he developed an “arc and time clock” useful for navigating long-range bombing runs.

It is, sadly, the lot of many visionary men to suffer the slights of the public and the media. A 1931 British Pathe film clip entitled “Another Good Idea Goes Wrong!” 34 shows Poirier launching a plane powered by twenty-eight rockets; it quickly crashes. “Inventor Poirier’s novel craft goes like a rocket—but comes down like a stick,” says the title card, crushingly.

So, was Maurice Poirier another J.W. Fawkes Jr., a somewhat crazed man with an overactive imagination? No. We can find five patents for him (1936, two in 1938, 1951 and 1956), all dealing with providing suspension of each wheel in a vehicle physically separate from the others—what we now call independent suspension. Poirier may have been the father of it, as least as far as transportation vehicles and trucks are concerned, which were the subjects of his patents. It perhaps goes without saying, in our off-road and utility vehicle society, that independent suspension is an important automotive development. Poirier played his part in making our car rides a bit smoother.

CLARENCE B. “KELLY ” JOHNSON

Like Willis Haviland Carrier, the father of modern air-conditioning, 35 Kelly Johnson was a man who might be termed an engineer’s engineer. A famous aeronautical genius and two-time Collier Trophy winner, Johnson, the head of Lockheed’s celebrated Skunk Works, was involved in the design and production of many groundbreaking and innovative aircraft: the Model 9D Orion, various Electra models, the Model 18 Lodestar, the PV-1 Ventura, the P-38 Lightning, the multitudinous Constellation family of aircraft, the F-80 Shooting Star, the P2V Neptune, the XF-90, the F-94 Starfire, the X-7, the F-104 Starfighter, the F-117A Nighthawk, the C-130 Hercules, the U-2, the Blackbird family and the JetStar/C-140. What an incredible résumé!

Johnson, musclebound from his early days as a hod carrier, 36 was able to use the same golf club for all his shots. But he was also a gifted mathematician, reportedly able to do accurate estimates involving lengthy sequences of calculus in his head. In fact, he performed calculus the way other people doodled.

Why was his Lockheed organization called the Skunk Works? As a teenager, Wes Clark asked his father that question and got the response that there used to be a lot of skunks around the plant in that part of Burbank. The Wikipedia article on Kelly Johnson has the real answer:

Johnson became Vice President of Advanced Development Projects (ADP) in 1958. The first ADP offices were nearly uninhabitable; the stench from a nearby plastic factory was so vile that Irv Culver, one of the engineers, began answering the intra-Lockheed “house” phone, “Skonk Works!” In Al Capp’s comic strip Li’l Abner, Big Barnsmell’s Skonk Works—spelled with an “o”—was where Kickapoo Joy Juice was brewed. When the name “leaked” out, Lockheed ordered it changed to “Skunk Works” to avoid potential legal trouble over use of a copyrighted term. The term rapidly circulated throughout the aerospace community, and became a common nickname for research and development offices; however, reference to “The Skunk Works” means the Lockheed ADP department .

Clarence Kelly Johnson and Amelia Earhart inspect airplane specifications at Lockheed, 1930s. Burbank Historical Society .

Ben Rich’s book Skunk Works contains a lot of interesting Kelly Johnson lore. There’s an amusing chapter entitled “Blowing Up Burbank” that describes Johnson’s development of what became the famous U-2 spy plane, powered by jets burning liquid hydrogen (necessary for the extremely high operating altitude of the aircraft). One day in late 1959 there was a fire in the Skunk Works near containers, holding seven hundred gallons of extremely volatile liquid hydrogen. The Burbank Airport came very close to being blown up. Rich describes the scene with the Burbank firemen:

The fire department noisily arrived at our hangar door and the next problem was that security didn’t want to let them in. The firemen weren’t cleared and this was a project above top secret.…“What is inside?” the fire chief asked me. “National security stuff. Can’t tell you,” I replied. The firemen saw the fog and went running for their gas masks. Had they known they were playing around with liquid hydrogen so close to Burbank Airport, I’m sure they would have had my scalp, but they put out the fire in two minutes and went away, no questions asked .

How is Kelly Johnson a Burbanker? He worked long hours at Lockheed from 1933 to his retirement in 1975, and the 1940 Federal Census shows him living at 1027 Country Club Drive—coincidentally, a few houses away from Burbank’s aviation legend and Nazi agent Laura Ingalls (whom we cover in the next chapter). While he lived elsewhere during much of his time at Lockheed, the city proudly claims him.

VOLMER JENSEN

While his creations didn’t fly as high or as fast as those of Kelly Johnson, Volmer Jensen nonetheless made his mark in the world of personal aviation, creating small aircraft that were safer and more affordable than those previously available.

As a young man in Seattle, he learned to fly a hang glider, the design for which appeared in an issue of Popular Mechanics . He then began to build other hang gliders, and by 1930, he had a worldwide reputation as a sailplane (glider) pilot. Beginning in 1937, when he moved to Glendale, California, he began to build light craft of his own design. One such, the VJ-10 high-performance sailplane, was purchased by the military for its assault glider training program. Jensen spent the war years as an instructor; when the war ended, he began to envision an affordable airplane. This became the VJ-21, which, sadly, never got to the marketplace due to economic factors out of his control.

By the 1950s Jensen had developed an interest in scuba diving, and in 1958 he marketed the VJ-22 Sportsman, a two-seat, high-winged, amphibious plane. Interest in this aircraft took Jensen into the light airplane business, and today VJ-22s are found on every continent save Antarctica. In the late 1960s, when hang gliders became popular, Jensen introduced the safe and sturdy VJ-23 Swingwing, which evolved into the VJ-24E SunFun. Dave Cook flew one across the English Channel in 1972.

Volmer Jensen was a master craftsman who had the reputation of being able to build anything. He founded the Production Model Company on East Providencia Avenue in Burbank, where, in December 1964, he rolled out his most instantly recognizable product, the original USS Enterprise from the 1966–69 Star Trek series. The piece is now in the Smithsonian Institution. (A photograph of Jensen and his Enterprise appear later on in this book.)

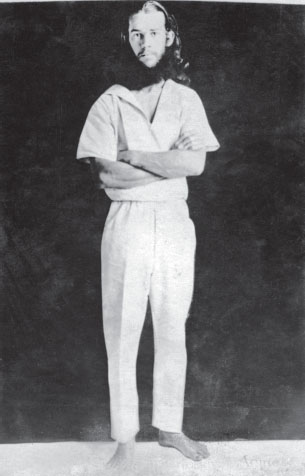

BURBANK ’S LOST LANGUAGE

We conclude our survey of Burbank inventors with this curious gentleman. Your authors are aware of a photograph of a barefooted gentleman, long of hair and beard, dressed in what looks like some kind of white institutional shirt and trousers (a 1924 Los Angeles Times article claimed he wore “picturesque garb”). His arms are crossed, and he stands gazing at the viewer with a morose expression on his face that almost says, “What of me?” 37 He is Harper B. Henry, described as living on a Burbank hill in the style of a hermit. The piece acknowledges that he looks like a fanatic of some kind but isn’t. What has he invented? A new breakfast food (the art on the cover of the box was done by him), a vehicle of some kind that was described as a sort of pink zeppelin on wheels and his own language, “Azonic” (a language of ideas independent of emotion, not of words). Why did he invent Azonic? “I am doing it purely for my own amusement!”

There are twelve characters in Azonic and six punctuation marks. The twelve characters describe not sounds, but twelve basic principles of nature. It will be appreciated that with basic principles of nature such as “unit substance” and “unit force,” trying to parse an object in Azonic is not for the faint of heart. A sheet of paper, for instance, is rendered in Azonic as “a plane of dead vegetable matter.” (A cynical observer notes that the same could be applied to a garbage can run over by a truck.) Azonic also has within it a time-reckoning system, the base of which is, of course, the day Azonic was founded.

Harper B. Henry, inventor of the Azonic language, in picturesque garb, circa 1924. Collection of Michael B. McDaniel .

Eat your heart out, Mattel! This clever wooden airplane was built by the Seaver Toy Company in Burbank. Collection of Michael B. McDaniel .

As an invented language, Azonic stands with Tolkien’s Elvish, Star Trek ’s Klingon and Zamenhof ’s Esperanto—just far less successful, as fewer people write in it. (We guess that back in the 1920s, that number was exactly one.) Not even Burbankers have heard of Azonic. Later in life, after rediscovering a long-lost daughter, Henry led a Utopian community on an island off the coast of Panama.

Harper B. Henry’s father was an unusual fellow, too. From 1913 to about 1930, Leroy “Freedom Hill” Henry lived in what is today the Shadow Hills section of Sunland (then Roscoe) and issued philosophical pamphlets from a Burbank address (back then, the Burbank post office served this part of Roscoe). His musings included “Freedom from Fond Friends,” “The Divinity of the Devil,” “The Usefulness of Useless Husbands” and “Henry’s Glass Eye.” That last one was actually about Henry’s real glass eye.

An interesting family!