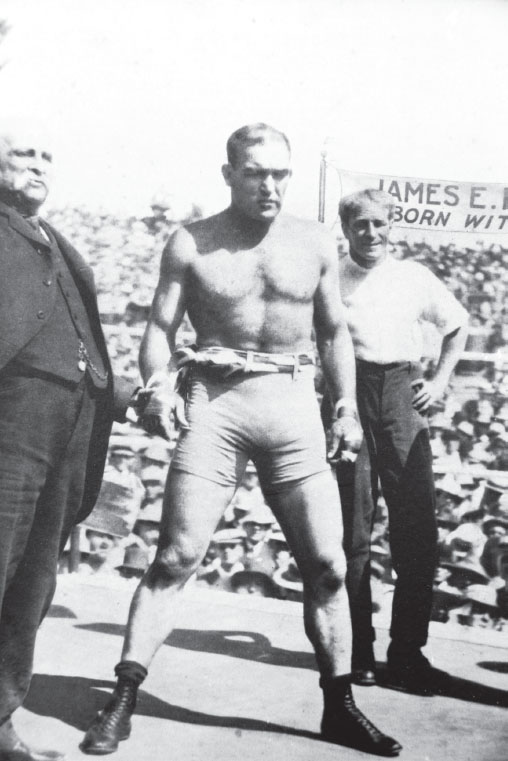

Big Jim: James Jackson Jeffries, heavyweight champion of the world, in his prime. Library of Congress .

7

THOSE AMAZING BURBANKERS!

This chapter celebrates people living or working in Burbank: Burbankers. These can be ordinary citizens whom you do not know, celebrities you do know or celebrities from the past who are now forgotten. But each has his or her story.

JAMES J. JEFFRIES

In Burbank history books, James J. Jeffries is always cited as the town’s first national and international celebrity—and so he is. But these books never look at his career as a boxer, other than to cite his heavyweight championship of the world. Let us look a bit more into the lost lore of the amazing physicality of Burbanker James J. Jeffries.

At six feet, one and a half inches and 225 pounds in his prime, he was called “Big Jim.” Look at that physique! Jeffries had a build any man in any era would envy. His upper-leg development was unique for his time, too. He could sprint one hundred yards in just over ten seconds—still impressive in our day and age—and he could high-jump over six feet. Gilbert Odd, an author on boxing, wrote, “According to those in Jeffries training camp, Jeff, a lover of hunting, once killed a large deer and carried it on his shoulders nine miles to camp without stopping to rest. Friends who accompanied him had difficulty keeping up with him on the jaunt home.”

Big Jim: James Jackson Jeffries, heavyweight champion of the world, in his prime. Library of Congress .

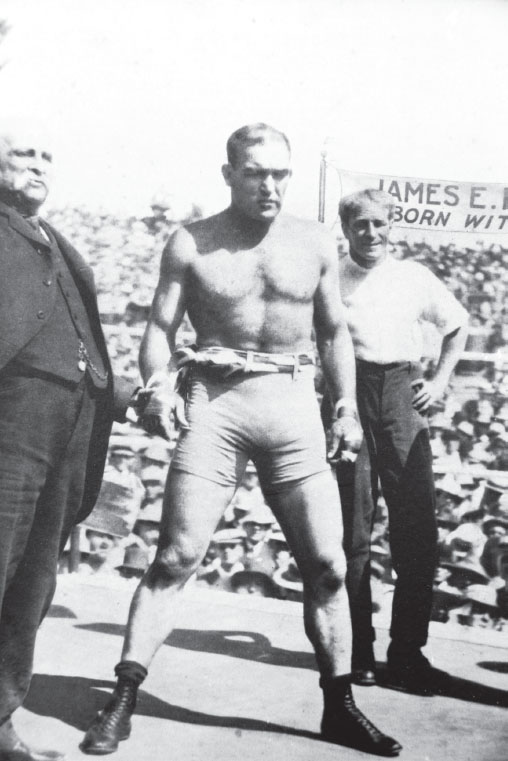

Big Jim in later days, playing Santa for Debbie Reynolds (left), Alice Kelly (center) and an unknown lass, 1948. Burbank Historical Society .

Jeffries was well known for being able to absorb great punishment in the ring. In his 1902 bout with Bob Fitzsimmons, one of boxing’s hardest punchers, he was viciously battered for eight rounds, with a broken nose, his cheeks cut to the bone and gashes over his eyes. Just as it appeared the fight would have to be stopped, Jeffries threw a hard right to Fitzsimmons’s stomach, followed by a knockout left hook to the jaw. Jeffries retired undefeated in 1905. 38 His accolades were many: “Champion of Champions,” “the greatest Heavyweight Champion that ever lived,” “the greatest fighter of all time.” Such was the boxing legacy of the man who established a ranch, a boxing ring in his barn and alfalfa fields at the intersection of Buena Vista Road and Victory Boulevard in Burbank.

For a macho man who lived by his fists, one is impressed by the soundness of James Jeffries’s holdings and investments. His acquisition of real estate in Burbank was canny: with 107 acres, he had enough land to become a rancher and maintain his interest in boxing, training new fighters and staging bouts in his barn. He also held rodeos on his property, and the Jeffries Ranch became the site of many civic and philanthropic activities. When the alfalfa market declined, he raised cattle on his property, eventually establishing a herd of thoroughbred bulls for export to Mexico and South America. In the business world, that’s called a diversified portfolio.

James J. Jeffries died an honored and respected Burbanker in 1953. 39 A plaque was placed on Buena Vista Street in his memory. The lore is that Jeffries collapsed on the sidewalk running alongside Buena Vista Street, and the plaque was placed at the spot.

LAURA HOUGHTALING INGALLS

Let us state immediately that in this section we are not talking about Laura Ingalls Wilder, the author of the Little House books. As far as we know, the two are not related.

In today’s parlance, Laura Ingalls had it all. She was a celebrated lady flyer in the early years of aviation who held a number of records, including the longest solo flight ever made by a woman (seventeen thousand miles), the first solo flight by a woman from North to South America, the first solo flight around South America by man or woman, the first complete flight by a land plane around South America by a man or woman and was the first American woman to fly solo over the Andes mountain range. Obviously, four of these, being “firsts,” still apply, ensuring her fame.

She had important and influential friends, with whom she posed for a photograph near her Lockheed Air Express plane in the Lockheed plant in Burbank: Amelia Earhart and Roscoe Turner (a barnstormer and personal friend of Howard Hughes). In 1934 Ingalls won the Harmon Trophy for her aeronautical skills and achievements. She had great publicity: a 1935 Universal newsreel, seen by millions, described the occasion of her being granted her transport pilot’s license. A 1938 article in the New Haven (CT) Sunday Register , entitled “Woman’s Place Is in the Air,” was highly laudatory: “A girl flier, with no time for love, would lift her sisters from the kitchen to a cloud…flying is their field as much as man’s—and the sky’s the only limit to their latent aeronautical abilities.”

Laura Houghtaling Ingalls, pioneer female aviator and Nazi spy, 1935. Burbank Historical Society .

Laura Ingalls was a daring new role model for young women; she was flying high, figuratively and literally, as an early feminist heroine. It makes her subsequent activities and publicity puzzling in the extreme.

The website Pardonpower.com gives an account of an interesting 1939 flight:

On September 26, 1939, Ingalls took the flight that doomed her legacy of extraordinary flight to scorn, if not general obscurity. Serving the interests of the Womens’ National Committee to Keep the United States Out of War, Ingalls flew over the nation’s capital for two hours and dropped red-white-and-blue “peace pamphlets” addressed to “All Members of Congress.” Officials of the Civil Aeronautic Authority (CAA) greeted Ingalls when she arrived at Washington Airport. They abruptly informed the aviatrix that her leaflet dropping was unacceptable given the fact that she had not been granted permission to do so by the CAA or the municipality of Washington. She was also informed that her flight had violated a restricted zone (including the White House). Ingalls was ordered to show cause why her license should not be revoked .

Three days before Christmas, the CAA suspended Ingalls’s pilot certificate for this ill-considered activity.

The trouble, as reported by the Los Angeles Times , really began in January 1942, when she was indicted in a Federal District Court for being an unregistered paid agent of the German Reich, in violation of the Foreign Agents Registration Act. She was charged with attempting to influence public opinion via isolationist speeches and distribution of printed matter. She pled not guilty but was tried and convicted as a Nazi agent in February. Details that came out in court didn’t help her cause: she wore a swastika pendant, called Hitler a “marvelous man,” berated President Roosevelt for helping England instead of Germany, received money from a German contact and concluded letters with “Heil Hitler!” She was quoted as saying, “This country needs somebody like Hitler,” “Democracy is the bunk” and “The H.M.S. Hood was sunk today. Seig Heil!” In her defense, her lawyer stated that Ingalls had offered her services to J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI as a Mata Hari but was rebuffed, which angered her.

Ingalls was sent to prison in Washington, D.C., where inmates, not amused with her Nazi racial beliefs, beat her as the culmination of a series of near riots she reportedly started. She was moved to a facility in West Virginia, and in October 1943, she was released. Eventually Ingalls moved back to Burbank and resided in a home on Country Club Drive.

Laura Ingalls died on January 10, 1967, in Burbank, aged seventy-three, and was buried in Kingston, New York. Her obituary in the Burbank Daily Review doesn’t mention her Nazi affiliation or her prison sentence. To the end of her days, she told friends that she had not said or held opinions different than those of American hero Charles Lindbergh (who was accused of being a Nazi sympathizer), but that she unfairly paid a penalty for them, whereas he had not.

DE LOS DICKSON WILBUR

DeLos Dickson Wilbur somewhere in the Verdugo Hills, 1917. He took this image of himself while on a postal delivery run. Apparently he used a pneumatic bulb to close the camera shutter. You can barely see the tube at his feet. Collection of Michael B. McDaniel .

A few years back Mike McDaniel came across an interesting and important collection of early Burbank photographic history, loose pages from the scrapbook of DeLos (pronounced “day-loss ”) D. Wilbur, an early resident. DeLos Dickson Wilbur was born on March 31, 1893, in Illinois, the son of Andrew L. and Hattie C. Wilbur. He had a younger brother named DeWitt Wilbur, born in 1896. In 1900 the family was still in Warren, Lake County, Illinois, but sometime between then and 1910 they moved to Burbank and took up residence in a house at 810 East Angeleno Street. DeLos graduated from Burbank High School on June 16, 1911. At some point he became a rural mail route carrier in town; it is unclear what his route was, but it appeared to have taken him well out of town.

He registered for the draft in 1917 and went to Washington State for training. He was assigned to the 185th Aero Squadron in France, working as an airplane mechanic. He returned to Burbank after the war (he is named in the 1944 Burbank Community Book as a World War I veteran) and resumed work as a mail carrier in Burbank.

At some point he seems to have struck up a friendship with members of the Luttge family, a prominent family in Burbank who owned a grocery store on San Fernando Road. In DeLos’s photos they are shown in front of their store in Burbank and at a beach.

DeLos and his wife, Lucile, had three kids, Doris (born in 1919), Wesley (born in 1921) and Lynn (born in 1926). The Wilbur family moved to Oceanside, California, between 1938 and 1940 (he and his wife living with their daughter Doris), where he is listed on the voter registry. Little is known beyond that. He died in August 1978, aged eighty-five. He was mentioned in an Oceanside, California paper as being a member of a local photo club and gave a slide presentation in 1956.

Wilbur’s enthusiastic amateur photography captured a charmingly rural Burbank that has long since vanished and been replaced by the thoroughly modern city we know now. Some of the photographs of San Fernando Road show buildings and locations that, to our knowledge, appear in no other known photographs. The great majority of the images are from early 1917, an era when the motorcar was beginning to replace the horse and buggy. Burbankers owe Delos Wilbur thanks not only for his service in World War I but also for his photographic documentation. (These may be viewed on the Burbankia website.)

DEBBIE “FRANNIE ” REYNOLDS

Debbie Reynolds is, of course, a film legend and has been for decades. But in the beginning—and by that we mean May 1948—she was just Mary Frances “Frannie” Reynolds of 1934 Evergreen Street in Burbank, a sixteen-year-old Burbank High School student and Miss Burbank contestant. The contest was sponsored by Lockheed, and every girl who entered was guaranteed a blouse and a scarf. In her autobiography Debbie, My Life , she describes herself as not especially pretty or glamorous (she didn’t even wear lipstick) and doubtful of the outcome. After all, her bathing suit had a hole in it (stitched up by her mother.) But she wanted the blouse and scarf.

What Mary Frances had in spades, however, was a winsome personality and charm. When asked on stage why she wanted to be Miss Burbank, she readily admitted that she really didn’t—she was in it simply because she lived in Burbank. During the talent portion of the pageant, she won over the audience by lugging a record player and nearly tripping in her high heels, which, after permission was gained from the audience, she removed. She then sang a tune, “I’m a Square in the Social Circle.” After that, she attempted to simply go home but was prevented by a contest official. When it came time to announce the three winners, in the beauty, talent and personality categories, Mary Frances was called out as the winner in the latter category, and the crowd went nuts.

A very young Debbie Frannie Reynolds comes to the microphone, circa 1948. The man is unknown. Burbank Historical Society .

The rest, as they say, is history. After winning the Miss Burbank contest, Mary Frances got a seven-year contract from Warner Bros., for which she worked while attending John Burroughs Senior High School, where she transferred from Burbank High. (For years her photograph was part of a student montage above the Burroughs auditorium doors.) While at Warner’s, she also worked for a time in the women’s clothing section of the downtown Burbank J.C. Penney. With her earnings from Warner Bros. she bought her parents a swimming pool for the house on Evergreen Street. After Mary Frances became Debbie and moved out, however, her father had it filled in with dirt—a situation that was only reversed when the house was sold in the early 1970s. (Her father felt that he alone should be responsible for improvements to the home.)

A Los Angeles Times piece from December 29, 1949, is worth noting: Miss Debbie Reynolds and another girl, two of Burbank’s civic queens, served as honorary timekeepers in a wrestling match 40 held in the Jeffries Barn to raise funds for the Burbank float in the Tournament of Roses competition. Debbie Reynolds, the Jeffries Barn and the Burbank float: it doesn’t get much more Burbank than that!

JAY LENO

Readers will know that comedian Jay Leno was the host of The Tonight Show on NBC from 1992 to 2009. Burbank is the site of Jay’s automobile garage, located near the airport. Leno owns approximately 286 vehicles—169 automobiles and 117 motorcycles. A television and web show, Jay Leno’s Garage , is based on his collection. The show includes lots of footage of Burbank streets. Leno can be seen occasionally driving around Burbank in some fantastic old or classic car; Mike McDaniel once saw Leno at the wheel of a Stanley Steamer on one occasion and in a 1966 Ford Galaxie on another. Fun fact: Jay Leno’s stated favorite employee at the Ralph’s grocery store on Buena Vista Street and Victory Boulevard is Mike’s son Nate.

JOHNNY WEISSMULLER

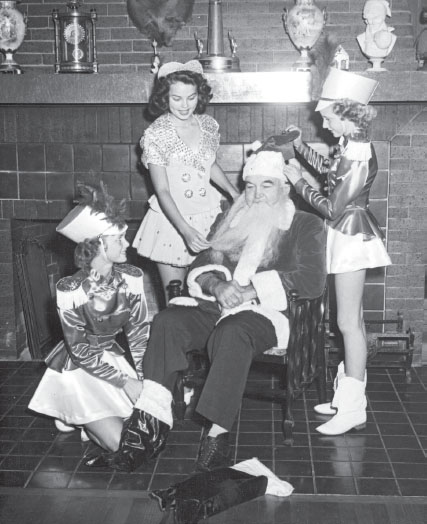

Johnny Weissmuller was the star of the Tarzan films (1932 to 1948) and the Jungle Jim films (1948 to 1954) and an actor who was billed by MGM as being “the only man in Hollywood who’s natural in the flesh and can act without clothes.” Weissmuller, six feet, three inches tall and 190 pounds, was a champion swimmer and winner of five Olympic gold medals, sixty-seven world titles and fifty-two national titles. He held every freestyle record, from one hundred yards to the half-mile. Swimming being important to him throughout his life, it was natural that, when the original Burbank Country Club, with its large pool, came up for sale, he purchased it. According to Country Club Drive authority Doris Vick, Weissmuller made a home of the facility from at least 1960, when Vick took up residence in the canyon, to 1962, when he sold the country club to the family from whom the City of Burbank purchased the property in order to build a spillway dam.

A 1920s photograph of the pool at the old Country Club building, later Johnny Weismuller’s. Collection of Michael B. McDaniel .

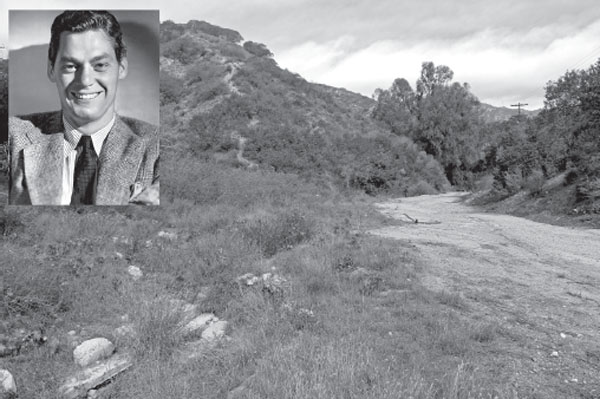

The Country Club/Weismuller pool site today. Johnny Weismuller is shown in the inset. Wes Clark/Wikipedia .

BILLY BARTY

Barty was a physically small actor with an outsized talent, reputation, sense of humor and style. The authors are happy to credit him as a Burbanker. Billy Barty was born William John Bertanzetti in 1924; the Internet Movie Database lists him with no fewer than 189 films and television appearances. Known for his enthusiasm and energy, in 1975 he founded the Burbankbased Billy Barty Foundation (first in North Hollywood, later on 929 West Olive Avenue), an advocacy group for little people, helping them integrate into mainstream society. Wes Clark was delighted to once chat with Billy at a Washington, D.C., function, discussing Burbank, his participation in a softball team for little people in town he named the “Short Ribs” and his role as Mickey Rooney’s “kid brudder” in the Mickey McGuire film series (1927 to 1934). Barty was a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and worshiped in nearby Studio City. He can be seen in a YouTube video from 1989 singing “The Sheik of Araby” and other tunes in a now-defunct Irish pub in Burbank.

Billy Barty’s business card, given to Wes Clark at a 1988 party. Collection of Wes Clark .

HENRY M. MINGAY

Civil War veteran Henry Mingay, for whom Mingay Elementary School in Burbank is named. A frequent speaker in city schools, he is shown here in his Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) uniform. The Burbank Historical Society has his hat and many of his medals. Burbank Historical Society .

Wes Clark, a Civil War buff, listened with interest when his father-in-law, Don Bilyeu (Burbank High class of 1945), spoke of seeing the Burbank school presentations of a Civil War veteran who lived nearby. Who was this person? He was Captain Henry M. Mingay, U.S. Army (Company D, Sixtyninth New York Infantry Regiment, a part of the famous Union army “Irish Brigade”). The honorific obituary of the Burbank Daily Review (April 24, 1947) gives the details:

Passing of Capt. Henry Mingay, 100, Civil War Veteran, Mourned—Thousands of school youngsters and the city today mourned the passing of Capt. Henry M. Mingay, 100-year-old Civil War veteran, last survivor of the 69th New York Infantry and of the Glendale N.T. Banks post. He died yesterday at Sawtelle Veterans Hospital .

He was one of eight surviving Civil War vets left in the state.…The Board of Education, in a statement issued today, said it “recognized again the tremendous influence of this soldier” on school children and expressed its sympathies to members of the family. In public ceremonies Dec. 5 1946, the city had officially dedicated the elementary school at Allan and Maple in Capt. Mingay’s honor. The student body, representatives from the various veteran organizations and school officials had participated in the fete. Three oak trees, symbolic of the old soldier’s strength and stamina, were planted and youngsters gave him gifts. The aged veteran had urged the youngsters to “be good.”

Capt. Mingay had appeared before countless school assemblies for over a quarter of a century, contributing much to instill in youth of this community an appreciation for true democratic principles and love of country, the board’s resolution read. Capt. Mingay, although failing in sight for the past several years, had enjoyed good health until recently when he broke a hip and was confined to his bed at the family home, 804 E. Elk, Glendale .

Born on Dec. 3, 1846 in Filby, England, the fourth son of Richard and Ruth Mingay, the boy and his family left for New York four years later in August, 1850. It took them six weeks to span the Atlantic in the old sailing vessel, America. He left school in 1860 to become a bootblack and printer’s devil on the Saratogian, Saratoga Springs, N.Y. When the Civil War broke out, he was refused enlistment because the “army is not signing up children.” But he got by on his second attempt and was sworn into the 69th Regiment. He saw action in all the regiment’s many battles and was mustered out as a sergeant. He was wounded in the right arm. Later he was commissioned a first lieutenant and was advanced to captain .

In a 1973 article on Henry Mingay, the Burbank Daily Review noted that when Warner Bros. filmed The Fighting 69th with James Cagney in 1939, the studio employed Mingay as a technical consultant. A studio limousine picked him up each day at his Tujunga home and whisked him out on location.

Henry Mingay was buried at Grand View Memorial Park in Glendale. He was described as living in, at various times, Inglewood, Monrovia, Tujunga and finally Glendale. Burbank, naming a school after him, claims him.

EDWARD W. SPENCER

The Wisconsin Historical Archive at Wisconsinhistory.org records a heroic tale that happened far from Burbank:

Around 2 A.M. on September 8, 1860, the steamship Lady Elgin collided with the schooner Augusta in the waters of Lake Michigan near Waukegan, Illinois. The Lady Elgin was carrying more than 300 passengers and crew on a round-trip sightseeing tour from Milwaukee to Chicago. Its return trip was never completed. The captain, not realizing how badly the ship was damaged, continued toward Milwaukee in the dark. About a half-hour later, the heavy boilers and steam engine broke through the weakened hull and the ship quickly tore apart. Most of the passengers and crew died. Only a handful reached the lifeboats. “Just when the Elgin took her final plunge,” the captain recalled, “a heavy sea took off the upper works, the cabin floated, and several hundred people got onto this.” . . . Seventeen people were saved that night by a Northwestern University student named Edward W. Spencer, who battled the breakers for six hours. An experienced swimmer, he had a rope tied to his body, and time after time swam through the waves to grab exhausted passengers. His associates on the other end of the rope then pulled him and the victim to shore. Finally, having reached the limits of his strength, his body covered with scrapes and bruises, Spencer passed out. He woke up in his room in Evanston where his brother, William, waited on his recovery. Edward’s first words were, “Will, did I do my full duty––did I do my best?”

Although he tried to resume his studies, the physical and emotional toll on Spencer had been severe. Newspapers around the nation praised his deeds but he was never completely comfortable with the attention. The faces and cries of the victims he had not been able to save forever haunted him. Spencer never completed his education, and it was almost fifty years before he returned to Evanston to talk about the wreck of the Lady Elgin. After his death, his brother described Edward’s private torment: “His face would turn ashen pale, and he would fasten his great hungry eyes on me and say, ‘Tell me the truth. Did I fail to do my best?’”

This maritime hero ended his days in Burbank; his February 8, 1917 obituary in the Los Angeles Times records that he lived at 220 San Jose Avenue.

There’s a footnote: In 1924 hymn writer Ensign Edwin Young heard the tale of Spencer’s heroism and was inspired to publish a song with lyrics that drew from Edward W. Spencer’s searching question. “Have I Done My Best for Jesus?” became quite well known.

OCTAVIA LESUEUR

The authors are fond of Miss Octavia Lesueur, who, in her obituary, was called Burbank’s “Grand Little Lady.” As children we played in Burbank’s parks, and we feel she’s owed some recognition. The best account of her contributions to Burbank is contained in a passage from the 1944 Burbank Community Book :

Burbank’s “Grand Little Lady,” Octavia Lesueur. Without her, Burbank parks wouldn’t be the same. Burbank Historical Society .

If a man can be designated as the “Father” of any worthwhile community movement, it is assumed that when the person happens to be a woman, she can be designated as the “Mother” of such a movement. On this assumption it is quite befitting to designate Miss Octavia Lesueur as the “Mother” of the park movement in the Burbank Community .

Before Miss Lesueur came to the aid of the trees, anybody who took a notion assumed the privilege of yanking out a tree whenever and wherever the spirit moved him. It was in a controversy over whether or not a certain group of trees should be removed that the Burbank Park system came into being. The uncertainty as to who should have the say on occasions of this kind brought forward the proposition of some kind of a system to protect the trees.…As a member of the Commission of Freeholders which drafted the City Charter, Miss Lesueur became an ardent champion of Parks and Playgrounds, and had an important part in mapping it out and establishing the Parks and Playgrounds Department. At first the two were operated separately, but later were joined together as Parks and Recreation Department. The Park Board during Miss Lesueur’s regime centered largely on planting trees in the parkways throughout the city. The more than 30,000 trees planted in those days are well matured and make an important contribution to the attractiveness of the city .

It should also be mentioned that in addition to being the owner of an insurance company, which she founded in 1919, and the first president of the Park and Forestry Commission, Octavia Lesueur helped to write the Burbank City Charter. She was a founding member of St. Jude’s Episcopal Church and the Zonta Club for women executives. This noble Burbank lady died on January 22, 1948.

PAUL E. WOLFE

City photographer Paul E. Wolfe. His photos are everywhere, but finding an actual image of the man is much harder! Collection of Michael B. McDaniel .

Doing Burbank research, one cannot help but encounter the many city photographs credited to Paul E. Wolfe; they are ubiquitous. Biographical information about him, in contrast, is scant. He was born in 1912 in Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania, and died in 1997 in Lancaster, California. He apparently moved into Burbank or Glendale about 1940. By 1946, however, he’s listed at 711 North Lima Street in Burbank. In 1963 he registered a business: Paul E. Wolfe and Associates, located on Victory Boulevard. He was cited as an official City of Burbank photographer in 1950; he also had a business taking baby photos at St. Joseph’s Hospital. We owe this gentleman a debt of thanks for so thoroughly documenting the city in midcentury.

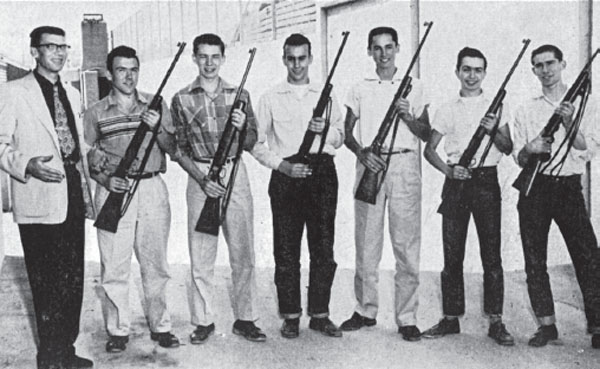

It’s difficult to believe today, but back in 1955, high schools had rifle and gun clubs. Here’s the Burbank High Rifle Club, armed and on campus! 1955 Ceralbus yearbook .