You have reached an important stage in your career, preparing to write a thesis or dissertation—a stage where many graduate students flounder. In 1997, D’Andrea reported that lack of structure in the dissertation process may be a key element in the failure of many students to complete their program. Yet in 2012 the lack of structure in the dissertation process continues to be a major obstacle in the completion of the dissertation (CPED, 2012; National Council of Professors of Educational Administration, 2011; Northern Illinois University Counseling, 2012). This book is designed to provide you with the structure you need to write a winning dissertation, which is a “done dissertation.”

Writing a winning dissertation begins with establishing a solid foundation. This chapter will help you establish such a foundation by understanding the special nature of the dissertation, and by making some preliminary decisions. As explained in the preface, the term dissertation is generally used throughout the work to refer to both master’s theses and doctoral dissertations. Since there are some differences, however, it seems appropriate to include in this introductory chapter an explanation of some crucial differences between the thesis and the dissertation.

Occasionally problems, both personal and professional, may develop for the student that may affect the “dissertating” process. To help you, a dissertating student, deal with such issues, this chapter will also assist in clarifying the roles of the committee and its dynamics. Furthermore, the chapter addresses how you might prevent and deal with some of the most common problems.

Like most writing, the dissertation is written to accomplish certain purposes with a specific audience—and its unique nature is perhaps best understood by analyzing purpose and audience.

Purpose is perhaps best understood by examining it from three perspectives: institutional purpose, personal purpose, and communication purpose. The institutional purpose is to ensure that the degree holder has made a contribution to the field as well as to uphold an honored academic tradition. The dissertation has an ancient history, because it originates at the medieval university where it was required of all those who wanted to teach. The dissertation now, of course, is perceived by university faculty as a demonstration of the candidate’s fitness to conduct and publish research, and to enter their scholarly ranks. The faculty also requires the dissertation because they take seriously the mission of generating and disseminating new knowledge. Furthermore, the dissertation is simply a widely accepted form for such dissemination.

You probably have several personal purposes in undertaking the dissertation. The foremost, obviously, is to earn the degree. However, you should view the dissertation as something more than an unpleasant requirement—what some students disparagingly call “the fee for the union card” or “the right of passage.” You should see it also as a way of learning. In the struggle to write the dissertation, you will learn much about yourself and about the topic you have researched. Writing is a way of knowing and thinking: The process of systematizing knowledge and finding a form to express that knowledge becomes a means of discovering meaning, or as several writers have put it, “I don’t know what I know until I try to write it.” Such learning will foster your personal and professional growth.

Your dissertation will be a better one if you take seriously the expectation that you will make a contribution to scholarly knowledge. Even though few dissertations report earth-shaking discoveries, the good ones add incrementally to the body of professional knowledge. Winning or completed dissertations extend knowledge, even if the topic has often been studied. Suppose, for example, that a dissertation reports research indicating that end-of-course testing was not an effective measure of student academic performance. That finding does not negate all the previous studies that found end-of-course testing to be an effective measure of student academic performance; it simply says to future researchers that the issue requires additional study.

The communicative purpose is clear and simple: You write to report the results of research. You do not write to persuade, to entertain, or to express personal feelings—but to inform. That informing function indicates that the primary quality of the writing is clarity, not creativity.

All these purposes—the institutional, the personal, and the communicative—interact to shape the dissertation in a special way.

Your audiences are also several. You write for yourself, of course, and you must be satisfied with what you have written. When you have finished the dissertation, you should feel a sense of pride in what you have accomplished.

You write for your committee, and their predilections, preferences, and idiosyncrasies must be recognized and addressed. In a way, they are the most important audience, since they will scrutinize your dissertation most carefully. Although others may give it only a cursory look, the committee will examine it page by page.

You write for the faculty as a whole, and institutional standards must be met. The faculty will award you the degree, and the requirements they have set for the dissertation’s form and content should be respected, even if they may seem unreasonable to you.

Finally, of course, you write for other members of your profession. Your dissertation will become a small part of a complex information network; your findings and conclusions will be read by other doctoral students and researchers in the field.

What results, then, from this intersection of purposes and audiences is a special type of writing. The dissertation is a report of research intended primarily for a scholarly audience. It is not a longer version of a term paper. It is not an anecdotal account of your professional success. And it is not a personal statement of your philosophy or a collection of your opinions. It is an objective, documented, and detailed report of your research.

Although the specific requirements for the dissertation will vary from department to department and school to school, it is possible to identify certain general characteristics that derive from this analysis of purpose and audience. First, dissertations are long—longer than a term paper, shorter than a book. The average length of dissertations seems to be approximately 200 pages, usually ranging between 125 and 225 pages. Those are only general guidelines, of course. There are differences in fields of study: Dissertations in the natural sciences tend to be shorter than those in the social sciences. There are differences in methodology: Dissertations reporting ethnographic investigations tend to be longer than those reporting experimental studies. The practical advice here is simply to write the dissertation so that it is long enough to tell your story without boring your committee.

Second, dissertations look scholarly—they contain citations of previous research. Your dissertation is expected to build upon previous knowledge, and as an inexperienced research scholar you are expected to know the literature and be able to cite it appropriately. You can’t simply make assertions; you must document them. The journalist writes, “The skills and duties required of a superintendent today differ greatly from those required over 100 years ago.” The scholar writes, “According to several recent studies (Boldt, 2004; Candoli, 1995; Cuban, 1976; Kowalski, 1999) many practicing superintendents agree that the superintendent position has gone through fundamental changes since the first school superintendent was appointed in 1837.”

Third, dissertations sound scholarly. While there seems to be a trend away from the highly formal style and a reaction against turgid academic prose, there is still the expectation that the dissertation will sound scholarly. Your dissertation should not sound like an informal essay or an editorial; it has to sound like the writing of a scholar. Furthermore, scholars write in a style that is formal, not colloquial, and is objective, not subjective. The letter writer says, “We’ve had a lot of rain these past few weeks.” The scholar writes, “Rainfall for the period June 1–30, 2009 was measured at 10.2 inches, 3.6 inches above the seasonal average (Shew, 2010).”

Dissertations are also organized in a special way. Although there is increasing variation in how dissertations are organized, most still follow this time-honored pattern: Introduction, Review of the Literature, Methodology, Results, and Summary and Discussion. Even those who vary from this standard pattern follow a predictable order in which the variations are minor: tell what problem you studied; explain how you studied it; report the results; summarize and discuss the findings.

Dissertations tend to follow very specific rules about matters of style. Although instructors vary in their requirements for handling tables, writing headings, and documenting sources, there is much less variation tolerated in dissertations. Every profession has its preferred style guide, and dissertations are expected to follow those guides religiously. One of the first things to check with your dissertation chair is the style guide preferred, since most universities have their own guidelines. (Throughout this book the term chair is used to designate the faculty member primarily responsible for directing the research and guiding the writing of the dissertation; in many universities the terms adviser or director may also be used for this role.)

There are several ethical considerations to keep in mind as you do your research and report your results.

First, you must be certain that the study is consistent with generally accepted ethical principles. The following principles should be kept in mind at all times:

You also should be sure to secure the informed consent of participants. The term participants is broadly used here to mean any who are involved in your research. Suppose, for example, that you wish to conduct a study in a local high school of the effectiveness of a program designed to improve students’ self-esteem. Here are all those who should give their informed consent: the school board, the school principal, the teachers whose classes will be involved, and any experts whom you ask to review the materials. You should also secure the approval of students and their parents, if students’ instructional program(s) will be significantly affected. All those individuals should know what you will study, which methods you will use, and why you are conducting the study. Knowing that teachers are sometimes reluctant to complete surveys for dissertations, some graduate students will conceal that fact, pretending that the study is being done solely for professional reasons. To act in this matter is clearly unethical.

Securing informed consent is generally interpreted to mean that you will provide at the outset honest answers to the following questions:

A standard form can be developed and then provided to all involved. One example is shown in Exhibit 1.1.

Another issue that needs to be dealt with at the outset is that of originality and collaboration. In your work as a graduate student, you will often work closely with and receive the help of other students and members of the faculty. Such professional collaboration has a long and honored tradition and has been the source of significant professional accomplishments. However, such relationships also raise a central issue of professional integrity. No written guidelines can ever cover all the delicate issues of who deserves credit for what. Perhaps the best guideline is one of simple honesty: Never claim credit for work that is not yours, and always give full credit to those who have helped you. The following advice is offered for dealing with some specific problems that frequently arise, both with the dissertation and with other academic papers.

Exhibit 1.1 Sample Information Form

Title of Study: Assessment Instruction: Secondary English Teachers’ Problems and Successes

Problem to Be Studied: What difficulties do secondary English teachers experience and what successes do they achieve as they try to design instruction based on performance assessments?

Rationale for Study: Secondary English educators throughout the nation are attempting to forge a closer relationship between performance assessment and teaching. Two initial studies indicate that student achievement improves when the linkages are strengthened. However, only one study to date has documented what happens when teachers try to use assessment-driven instruction. The study will be completed as the basis for a master’s thesis in English education.

Methodology: Two secondary English teachers will be selected for the study. They will be asked to keep a log of their experiences. Their students will complete two surveys (attached as Figures 1 and 2). The researcher will interview the teachers on three occasions—once in September, once in January, and once in May.

Participants: Two secondary English teachers who have been trained in assessment-driven instruction will be selected from volunteers. Neither their names nor the names of the district or the school will be identified in the study. One of their classes will also participate in the study.

Benefits and Risks: The benefits are both professional and personal. The study should add to the knowledge base for an important development in teaching. The teachers who participate will receive feedback about their attempts to use this new method. There are no risks involved to the teachers or their students—no more than minimal risk.

Time Commitment and Compensation: The total time commitment from the secondary English teachers is expected to be ten hours of their preparation or out-of-school time. Student surveys will require a half hour of class time. No one will be compensated for participating.

Obviously the most important ethical issue is not to fudge your results. Remember that in the most basic sense there are no failed studies if they are completed carefully; even negative results are important and add to existing knowledge. Also guard against the temptation to shade the language or let your biases be apparent.

The other preliminary matter that you must consider is being sure that you have the resources you need.

First, determine whether you will have the time needed to complete a winning dissertation. Ideally, you should have sufficient funds so that you can work on the dissertation full-time. If that is not possible, then you will have to find a way to become a “time manager” by setting aside extended blocks of time for your research and writing. You cannot write a winning dissertation in one-hour stints; you need extended time periods that will enable you to prepare, research, write, and revise.

The second key resource is hardware. You should have easy access to a powerful computer, adequate data storage, and a laser printer. Although it is possible to hire someone to do your word processing for you, it is not a good answer when considering your long-term professional career needs. Professors and educational leaders must learn to do their own word processing. With the continuing advancement of technology, the preparation of the dissertation is much easier than 10 to 20 years ago.

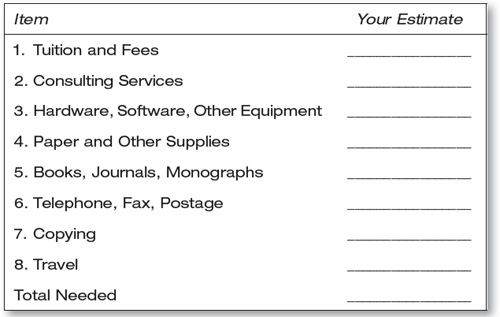

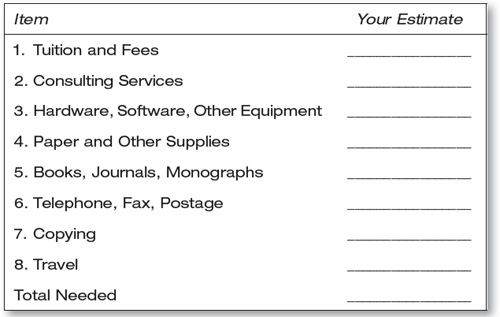

The third important resource is money. The budget worksheet shown in Exhibit 1.2 may help you make some estimates of the funds you will need. The items are explained briefly below.

You have to pay tuition for any courses you still must take. In addition, most graduate schools require you to pay a fee during the terms when you are working on your dissertation. Although some students complain about such fees, dissertation advising is a labor-intensive process, and your fees cover only a part of the costs.

You should determine whether you will have to pay for any of these services: stipend for participants, word processing, data entry, data analysis, editing, and copying.

As explained previously, you will need access to a powerful computer with adequate data storage and auxiliary data storage devices, and a laser printer. You may also need software for word processing and data analysis. Special projects may require other equipment such as a camcorder, camera, scanner, VCR, and DVD player or recorder.

You will find that you consume printer paper at a high rate as you write and revise.

Even if you have access to an excellent library, you will probably want to purchase some basic references so that you can make notes in the margins and keep them always accessible.

These are essential communication costs that mount as you do your research and send chapters to your committee. However, the cost of such communication is being greatly reduced with the use of e-mail, Skype, and other Internet-based communication.

You may need to make copies of instruments; you will certainly make multiple copies of each chapter. However, costs associated with photocopying may be reduced if your committee accepts an electronic version of the document.

If your research requires you to make on-site visits to distant locations, you will need a substantial travel budget. Yet with continued technological advancements and the use of the Internet, travel may not be perceived as necessary.

Also keep in mind that other students may provide a helpful resource. Some students have found it helpful to develop a support group composed of students who have reached the dissertation stage. Students reported that such a group was helpful to them in dealing with dissertation problems (D’Belcher, 2005; Melroy, 1994, 2002).

If you find that your needs exceed your resources, you should search systematically for special support. The first place to turn is to apply for a graduate assistantship. A graduate assistantship does more than provide you with extra funds: it enables you to work closely with faculty and staff, provides access to a scholarly network, and helps you develop the skills you need.

If a graduate assistantship is not available, consider applying for a grant from one of the foundations that support graduate research. The best source here is The Foundation Directory Online maintained by the Foundation Center (http://fconline.foundationcenter.org/).

As noted at the outset, the master’s thesis and the doctoral dissertation are both reports of scholarly investigations, completed as part of the degree requirements. All the aforementioned attributes apply to both scholarly works. Although institutional requirements vary, there are some general differences that should be noted here.

First, most master’s theses are more limited in scope and depth than doctoral dissertations. A master’s thesis might report on a study of grouping as used in classrooms in a particular region; a doctoral dissertation might compare the effects of two grouping systems in teaching elementary mathematics. As a consequence of this difference, doctoral dissertations tend to be longer than master’s theses.

Also, the doctoral dissertation is likely to be more rigorous in its research methodology than a master’s thesis. The thesis is more likely to seem like a “project report,” explaining, for example, how instruction was planned and organized prior to lesson delivery in a middle school. A doctoral dissertation on the same topic might be a detailed analysis of how teachers planned and organized instruction and how they used class time.

Noting these differences is not to depreciate the master’s thesis as a scholarly work. Many make important contributions to the field.

You first need to understand the roles and related responsibilities of the committee. Members of your dissertation committee are responsible for giving you the direction and assistance you need to complete the dissertation, but that responsibility does not mean that they are supposed to do any of the work for you. It does mean, however, that they should be available to you, within the limits of their other responsibilities. As members of the faculty, they are also responsible to the university to uphold the academic standards of that institution. This means that they cannot accept careless work just to enable you to finish your degree. As researchers and educators, they also feel a responsibility to the larger profession, to ensure that the dissertation makes a significant contribution to professional knowledge. As professors, they feel responsible to themselves and their career advancement. They have their own standards of quality and their own need to advance their careers. Finally, they have several personal roles that cause their own pressures—spouse, parent, and son or daughter.

Obviously, these are conflicting responsibilities that cause conscientious committee members to experience their own stress. For example, they want to be available to you, but they also need to research and publish if they are to receive tenure and be promoted. Or they want to help you finish in a reasonable time, but they believe that your dissertation needs much more work. They are reluctant to give you criticism that will result in your feeling negative about yourself or them, but at the same time they know that your work needs improvement. If you understand these conflicting responsibilities, you will be better able to deal with committee problems that develop.

Each committee will vary somewhat, depending upon the personalities of the members. However, three well-documented features of academic life will clearly have an impact on committee dynamics.

First, academic life is hierarchical. As a consequence, dissertation committees are hierarchical, reflecting the status distinctions of academic life. Full professors are at the top. Tenured associate professors come next, followed by nontenured associates. Assistant professors have a lower status—except for graduate students, who have the lowest status of all. Length of service at that university also affects status: faculty who have had longer periods of service tend to receive higher status than those who have less. These status distinctions suggest that there will be fewer intracommittee conflicts if the chair has higher status than other committee members. If your chair is an associate professor and a committee member is a full professor, the status distinctions might complicate their committee relationships. The harsh fact is that because you have the lowest status of all, you do not have the power to ignore committee recommendations and decisions.

Also, academic life is individualistic. As a consequence, most committees are fragmented and individualistic. Higher education does not tend to reward cooperation and collaboration. Many faculty members are promoted and receive tenure chiefly on the basis of their research and publication, with their advising having much less weight. These features mean that members have no strong incentives to meet together and work together. Although your committee members may meet with each other at faculty and departmental meetings, they will not be discussing your dissertation at such encounters. In fact, most dissertation committees come together only infrequently, at and prior to defenses. This feature means that you probably have to find ways of working with them as individuals, not as a group.

Finally, academic life is somewhat rigidly structured, with fixed roles and distinctions. This rigid structure usually holds true in committee work, too. The chair is clearly in charge, and the other members understand that their role is to assist, while acknowledging the authority of the chair. It is the chair’s reputation that is on the line when your dissertation is reviewed by other faculty, by the graduate school office, and by external members of the profession.

The key to positive relationships with the committee is preventing problems before they occur. You can do this in several ways. First, choose a committee whose members are compatible with each other and with you. Problems of relationships can often be avoided if you are sensitive to the matter when forming a committee. Thus, you, the dissertating student, should do your homework to determine the capability of likely professors to serve as committee members. You should review the completed dissertations from your department in the university library. While reviewing those completed dissertations, note those committee members whose names appear frequently. A dissertating student can learn those who work well together, because their names appear frequently on the dissertations’ signature pages.

Second, at a very early stage in your work with the committee, clarify the nature of the committee’s relationships with each other and with you. Most committees are structured in this fashion: The chair does most of the work involved in directing the research and the dissertation and is the primary contact with the student; a second member of the committee provides needed technical expertise; other committee members play a much less active role. Be sure you understand where you are expected to get the help you need—and how much help the committee wants to give you. Learn to use your committee without taking advantage of the members.

Next, determine the specific ground rules by which the committee expects to operate. At the proposal defense or immediately thereafter, you should consult with the chair and the rest of the committee, if necessary, to clarify all important procedural matters. It is to your advantage to obtain contact information from all committee members, and the information should be stored by you, the dissertating student, to use when communicating with the committee member or members.

Selecting a compatible committee and clarifying relationships and procedural matters should avert most of the difficulties that students encounter with their committees. The other suggestions for maintaining productive relationships with your committee can be summarized briefly:

Even if you have followed all these suggestions, there will still be some predictable problems resulting from the above roles and characteristics that might affect your progress.

For most committee members, providing assistance to doctoral students is a labor-intensive responsibility, one that is rather low on their list of priorities. This means that some committee members will be slow in giving you feedback—not because they are irresponsible but because of the conflicting responsibilities. The unwritten norm is two weeks for committee members to provide feedback. Obviously this will vary, depending upon such factors as the academic calendar, professors’ attendance at conferences, and their own involvement in research and publication.

When you experience what you feel are inordinate delays, you should deal with the problem differently, depending upon the source. If other committee members are slow in responding, e-mail a tactful reminder (without sending a copy to your chair, or if you decide to copy your chair, be sure that it is a blind copy) or telephone your concern. If they still do not respond, then simply report the facts to your chair and let him or her handle the problem.

What do you do if your chair is slow in responding to your chapters? First, as previously noted, you should attempt to clarify at the outset how much time is usually required; two weeks seems to be an unstated norm. The first few times you experience an inordinate delay, handle the matter as if you’re a very tactful bill collector. Call and say, “I’m calling just to be sure you received Chapter 2; I haven’t heard and was getting just a bit anxious. When do you think I might be receiving your comments on Chapter 2?” Then if you still haven’t heard by the date indicated, call again: “I’m calling just to inquire if there’s a special problem with Chapter 2; you indicated that I might be receiving it by today.”

If those tactful phone calls do not have the desired effect, talk the problem over in a face-to-face discussion. Express an attitude that’s reflected in these words:

I know you’re very busy, and I don’t want to make unreasonable demands. However, I am feeling frustrated by my lack of progress. I thought it might be helpful if we could talk the matter over. I want to determine in what way I may be responsible for the delays and take appropriate action.

The rest of the discussion should maintain this problem-solving orientation: How can we cooperate to reduce the turnaround time?

Sometimes the conflicting advice is from two different committee members; sometimes it comes from a single professor who changes his or her mind.

If you receive conflicting advice from two members of your committee (including the chair), let the chair handle the matter. Explain the conflict to the chair and ask how you should resolve it. It is the chair’s responsibility to mediate such differences; you should not be in the middle.

The problem of receiving conflicting advice from one individual is common. Dissertation students often justifiably complain that after they have revised a chapter according to their chair’s (or committee member’s) recommendations, they receive more revision suggestions from the same individual that conflict with those first received.

Here is a good process to use that will avoid this frustrating experience.

You may receive what you consider to be unhelpful advice or editorial comments. If the advice or comments are too general, call and ask for specifics. If you feel that you received counterproductive advice about a relatively common matter, accept it. It is not worth arguing over. However, if you feel that the matter is important, deal with the difference in a professional manner. If the unproductive advice comes from a committee member other than the chair, ask the chair to help you resolve the matter. If the unproductive advice comes from the chair, then meet to review the matter. In essence, communicate with the chair on a regular basis.

In a few unfortunate instances, graduate students find that their relationship with the chair or some other committee member deteriorates so badly that they feel the conflict is interfering with their progress. If the conflict is with some member other than the chair, ask for a meeting with just you and the member. In that conference, emphasize that you wish to solve a problem, not complain or blame. Use a problem-solving mode that makes these points:

If that face-to-face conference does not solve the problem, you should ask the chair to intervene.

If the problem is with the chair, you should use the same problem-solving approach in trying to resolve the difficulties in a private conference. It is probably unwise to ask another committee member to intercede on your behalf in this instance; doing so may place the member in an untenable position with the chair.

If you are convinced that the chair or a member should be replaced, be sure to handle the matter professionally. In doing so, keep in mind three useful guidelines:

You will also experience some personal problems in completing the dissertation. There is a small body of research and a large body of anecdotal evidence indicating that doctoral students experience some common problems throughout the dissertation processes. (For the research, see the following: Council of Graduate Schools, 1991; Germeroth, 1990; Huguley, 1989; Tadeusik, 1989; Whitted, 1987; the Writing Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2012.) Since the common problems seem to occur at specified times in the dissertation process, they are discussed here according to the stages during which they usually develop.

These problems can be crippling in their effects. Some estimates indicate that only 40 percent of all doctoral students ever finish. Although “dropping out” is often a result of financial and work-related factors, the emotional stresses associated with completing the dissertation undoubtedly play an important role. For a few students, these stresses will be serious enough to warrant professional counseling; for such individuals, no book can suffice. For the rest, however, some rational analysis of the problems and their solutions might be useful.

There seem to be four crucial periods when doctoral students experience serious emotional problems that relate to the dissertation: near the end of the course work, after completing course work and before writing the proposal, after the proposal hearing, and after the dissertation defense.

A large proportion of doctoral students withdraw from the program near the end of their course work. In many instances the reasons are valid ones, and withdrawal from the program is the wiser choice. They change career plans, choosing to follow a career where the doctorate is not essential. Their values and their priorities change; they decide that family, job, or personal enjoyment is more important than the prestige of having the doctorate.

Many simply do not have the money: Graduate education is becoming so expensive that many of the most promising students are withdrawing because they have grown tired of mortgaging their futures. Others withdraw primarily for emotional reasons; it is fear that most of all gives rise to the problems at this stage. From lack of knowledge and from their own insecurity, many doctoral students have come to fear the dissertation. They may try to conceal this fear by pretending that the degree is unimportant and the dissertation absurd—but it is there all the same, despite the forms it takes. The specific fears seem to be several. “I’m afraid that the dissertation will just take too much time.” This is a general fear that seems to color all other feelings. The dissertation seems like an impassable mountain; you probably have heard stories of students who have struggled for years without ever finishing. To a certain extent, this fear is justified; from choosing a topic to defending the dissertation can take as long as two or three years for part-time students. However, even a complex project like writing a dissertation can be accomplished efficiently with careful planning and conscientious effort; it is like a long journey that you make one step at a time.

The scheduling suggestions offered in Chapter 6 should help you cope with this particular anxiety. In addition, the following suggestions should help:

“I’m afraid I don’t have what it takes to do the dissertation.” That is also a reasonable fear, since writing the dissertation is a demanding task. The way to deal with this fear is to assess your capabilities as objectively as you can, with the help of a faculty member whom you respect and who knows you. Do not ask a spouse or a friend, “Do I have what it takes?” You will probably receive only well-intentioned encouragement.

Instead, do a systematic assessment of your strengths and weaknesses with input from someone who can be honest with you; the form in Exhibit 1.3 (see page 30) might be of help to you here. If you identify deficiencies, take steps to remedy them, if they seem remediable.

“I’m afraid of what the dissertation will do to my family and social life.” There is also a modicum of rationality in this anxiety. Dissertations take time, money, and mental energy, and many relationships have been strained during dissertation time. Here again there is an obvious solution. Instead of simply worrying about the matter, discuss it openly with your spouse. Examine together what mutual advantages will accrue from receiving the degree and what sacrifices must be made. How much will the dissertation cost in money—and where will the money come from? How will doing the dissertation affect the contributions you can make to child rearing and household maintenance? Can your spouse understand and accept the fact that you will often seem distracted, absorbed, moody, and perhaps irritable, especially on those bad days when you get back a chapter your chair has rejected?

“I’m worried about the financial costs of doing the dissertation.” The budgeting process suggested earlier should be of help here. Be realistic about the costs of doing the dissertation and about the resources available to you.

“I’m worried about the impact on my professional assignment.” At the outset of the entire process, discuss your plans with your supervisor, without asking for special treatment. If it seems feasible, choose a research topic that will be of help to your organization. As you experience conflicts between writing the dissertation and doing your job, try to find win-win solutions by making compromises and adjustments.

There are some real fears to be confronted and dealt with, but they are all surmountable.

Another critical period is after you have completed the course work and before you get to the proposal stage. Students who withdraw at this point are the army of the ABD’s—all but the dissertation. Again, there are often practical reasons operating: lack of money, change of plans, the onset of health problems. More often, however, the problems are emotional and psychological ones. The problems at this stage all seem related to a pervasive anxiety that results in prolonged procrastination. Notice how this student put it in a candid letter to a friend who asked about his progress:

Exhibit 1.3 Crucial Dissertation Skills and Traits

Doctoral student’s name: ____________________________________

Assessor: _________________________________________________

Directions: The student named above would like your candid assessment of his or her specific abilities, as they relate to completing the dissertation. For each crucial skill or trait listed below, circle one of the following:

| NP: | No problem here with this skill. |

| IM: | Some improvement is needed here, but the skill or trait can be remedied. |

| SD: | Seriously deficient; the deficiency seems so serious that it may be a major stumbling block. |

I’ve been paying my dissertation fees for five terms now and I still don’t have a proposal ready. I keep promising myself that this will be the term when I get the proposal in shape—but I never make it. I just can’t seem to get a fix on a good problem—everything important either has been studied already or is too big for me to handle. I make lists of problems—but nothing clicks. I talk to the professors and each one suggests a different problem until I’m completely confused. And I don’t think I have the research skills I need; I have always been weak in statistics. I guess, to be honest, if I did find a problem and could feel positive about my skills, I would still have trouble developing a proposal—I just don’t know where to begin. Some students talk about 150-page proposals. How could I ever write 150 pages about what I will study?

A statement like this reflects anxieties that most ABD’s have at one time or another. Aside from being colored by the general fears described previously, the statement reveals some specific concerns about the topic, the research skills, and the proposal. How to deal with these specific concerns is to a great extent the focus of this entire work. However, some general guidance can be offered at this point for dealing with dissertation anxiety and the resultant sense of being immobilized.

Your choices are clear: You can withdraw gracefully; you can continue to enrich the university’s coffers by paying your fees without making progress; or you can get your act together. It is as simple as that. Just stop making excuses to yourself.

All students writing dissertations experience several emotional highs and lows. Your data gathering goes well, and you feel euphoric. You get a chapter back with some caustic criticisms, and you feel crushed. A good part of being able to deal with the emotional problems encountered during the dissertation itself is knowing what form they will take and being prepared to deal with them. For the most part, the problems at the dissertation stage seem to be ones of doubt and uncertainty that take the form of predictable complaints.

“I’m tired.” Common complaints are physical and psychic fatigue; you just get very tired collecting data, sitting at the desk, pounding the keys. Your head starts to hurt, and you find yourself feeling irritable. You know the answers to fatigue: eat sensibly, exercise, get adequate rest, and reward yourself with a day off now and then.

“The data gathering is not going well.” All researchers, from the beginner to the expert, encounter predictable problems with the research itself. Questionnaires are not returned, subjects leave the study, instruments do not work as they should, or the data don’t act the way you predicted. The answer to such problems, obviously, is immediate communication with your chair. Do not wait, hoping things will be corrected; even if they are, your chair will want to know about and assist with the difficulties as they develop. And do not avoid confrontation, fearing that your chair will tell you to scrap the whole thing. Good chairs know how to salvage studies that start to go wrong. Moreover, in a scientific sense there are no failures in well-designed studies; “no significant difference” may be truly a significant finding.

“I keep finding references in the literature I want to cite.” It is a wise idea to keep abreast of current research as you do your study, but once you have reviewed the research for your dissertation, there usually is no need to add very current references. You can add current references to your own files and review them prior to the hearing, but it would be unwise to continue revising the literature chapter once it has been approved—unless you come across some truly important study that just cannot be ignored. Confer with your chair to set a reasonable date for concluding the search of the literature—in other words, when to cease with the literature review.

“I will be the last of my cohort to finish.” Such comparisons are inevitable but irrelevant: Writing a dissertation is not like running a race. All that matters is the quality of the work. Four or five years from now no one will remember who finished first and who last.

“I now feel that I chose the wrong topic.” This doubt seems to beset all doctoral students at some point. Just remember that there is no right topic and get on with concluding your study of the one you chose.

“I have writer’s block and can’t write.” Dry periods come to all who write. The best answer for writer’s block is to write: Sit at the word processor and force yourself to write, even though the product is not of the highest quality. You can always go back and revise. What you should not do about writer’s block is worry about it while you find excuses for not writing.

“I’m worried sick about the defense.” Reassure yourself with the knowledge that very few students fail the defense; a good chair won’t let you go to the defense until he or she is sure you are ready. Also, if you follow the suggestions in this book, you should have no problems at the defense. It will seem more like a final ritual of celebration than a test.

Note that most of those complaints seem to have a common thread of self-doubt, and that self-doubt is understandable. You feel tired. The end is not yet in sight. You are not getting much positive feedback. You seem close to the end of your resources. You are like a runner who feels tired at the halfway mark. At such a time you need to turn to whatever support is available—your peers, your chair, your spouse, your spiritual director—to help you find the inner resources to continue. Most doctoral students find support in networking with others at the same stage.

Most students find it difficult to believe that there can be any emotional problems after the defense, but many who have gone through the experience talk about the period right after the defense as a time of “postpartum depression.” It seems to be a general sense of emptiness, of bleak uncertainty.

The causes are understandable. There is first a predictable letdown. The doctor’s degree really has not changed things, and having “doctor” in front of your name has not markedly increased the respect that people accord you. You probably face some career dislocation. You pursued the doctorate because you wanted to advance professionally. Now you have the degree, and you face the trauma of job hunting. And there is often a sense of emptiness in each week. A major intellectual task that gave your days an organizing center is finished, and you have all that time now to use in some productive fashion. Maybe now you are no longer the center of attention in the household; that patient spouse who sacrificed for so long now expects you to carry more than half the load. And you take a look at your dissertation in its new binder and shake your head in dismay: it really wasn’t worth it after all.

The best way out of such depression is usually through meaningful action. After a suitable period of self-indulgence, decide what you want to do next professionally. Will you continue with your research? Will you publish from your dissertation? Will you try to develop a part-time consulting role? Will you actively seek a new position? Then make the plans that will help you accomplish what now seems important to you.

The rest of this book will take you through the complex process of writing the dissertation. Although the suggestions have been drawn from considerable experience in helping students produce winning dissertations, be sure that you check closely with your dissertation chair every step along the way.

The availability of the Internet has made and continues to make the “dissertating” process easier. Today’s graduate students now have the ability to search for relevant information from any device that is able to connect to the Internet—smart phones, tablets, laptop computers, and desktop computers. Searching for information is easier and quicker; however, one major concern is the credibility of the information located.

In today’s technological world, it is quite a simple task to upload information to the Internet. Anyone can create and upload a document to an Internet location without scrutiny; therefore, the quality and believability of such information needs to be considered by the reader of such information. The credibility of the information is enhanced if a reference list or bibliography is published with the document. As with all sources of information, graduate students need to be certain that the facts purported in such Internet documents are reliable before accepting the information for use in the dissertation (Wehmeyer, 1995). For determining the credibility of Internet information, if similar information is found in three sources, it is presumed to be credible.

Doctoral committee members who are concerned with maintaining academic standards question the use of the Internet. One reason is the credibility of the information. Another reason is the belief by some faculty that credible research can only be found in the library; and those faculty members think that dissertating students must spend multiple hours reviewing the actual journals, manuscripts, theses, dissertations, and so on in their hard copy formats in a campus facility. Thus, dissertating students should discuss the use of the Internet as a research tool first with their chairs. After determining their chair’s point of view, a conversation may be needed with the doctoral committee.