Late Medieval and Tudor Houses

1300–1560

1300–1560

FIG 1.1: LITTLE MORETON HALL, CHESHIRE: This rambling timber-framed house has, at its core, a 15th-century hall which over the following century was added to, with the famous gatehouse range pictured here being the final piece of the jigsaw in the 1570s. Typically for the period the composition of the house is irregular as rules on symmetry and proportions were unknown to its builder so it did not seem to matter that this main front, with its spectacular row of windows, had a garderobe tower (a toilet block) prominently positioned in the middle!

To start our journey through the history of the English country house, we need to turn the clock back some 700 years to the Middle Ages. It was a time when military might and the respect it commanded were of primary importance in the life of an aspiring lord of the manor. His household officers were his show of strength, with the size of his personal army and its loyalty to him acting as a barometer of his standing among fellow nobles. He, in return, provided a roof over their heads and regarded them as an extended family.

This community would travel with their lord as he moved from one of his estates to another; a surprisingly frequent event, perhaps occurring every couple of months or so, and involving a huge baggage train in which even the owner’s bed was taken along! This portable household, which included a wide social spectrum from young aristocratic knights down to local peasant boys, could number into the hundreds, although many would have been based on one estate and only worked when the lord was visiting. As these medieval manor houses were derived from the castles of the 11th and 12th centuries, they still played the role of a barracks and, hence, most of the household were male, even the entire kitchen staff.

At the head of this family stood the lord, a military leader and faithful Christian, strong in his dispensation of justice, yet hospitable to strangers at his door; a chivalrous and graceful socialite, as much at ease with the dance or the pen as with the horse and sword; and although few would ever have attained this ideal image, these were the expectations heaped on the aspiring noble. Therefore, not only did he have to worry about impressing his guests with huge banquets, feasts and entertainment (anything from half to three-quarters of his total budget would have been spent on food and drink), but he also had to build somewhere to house them and his increasingly large household. By the 15th century, castles and manor houses had been expanded to form the basis of what we would term a country house.

The Style of Houses

In this period the exterior style was not a major consideration in the design of houses. They were laid out with domestic function and military requirements in mind, hence they would appear to be a jumble of buildings set around a courtyard surrounded by crenellated walls, a moat, and accessed through an imposing gatehouse. Even though defensive features would hardly ever be tested in the relatively peaceful counties away from the turbulent border regions, they were used by the owners as statements of power and wealth; some even making their houses in the form of castles and naming them thus.

FIG 1.2: STOKESAY CASTLE, SHROPSHIRE: This manor house close to the Welsh border had defensive features like a tower (right) but later additions, as with the 14th-century hall (centre), were more focused on luxury and status.

FIG 1.3: Medieval framing, with its distinctive large panels and thicker, irregular timbers (left), was replaced during the 15th century by close-studding (centre) mainly in the south and east of the country, and small square-framing in the Midlands and the north; the finest with decorative pieces inserted to form elaborate patterns (right and Fig 1.1).

The buildings were generally vernacular, that is they were built using local materials and craftsmen. Only the wealthiest aristocrats, the Crown and the Church would import stone or use a notable mason or carpenter from outside the region. Most would have constructed the main parts of the house using methods passed down through the generations; with the only concession to fashion appearing in the detailing, like the shape of a window and door, or the style of the timber-framing. Stone from small quarries worked for just the one project tends to be found in highland areas of the north, the west and the limestone belt of central England, with timber specially reserved for the lord from within his manor being used in most other regions. Although the Romans introduced brick to these shores, after they departed it was not used again until the Late Medieval period, when it became a fashionable material for the finest buildings in the eastern counties.

The Layout of Houses

The plan of the main parts of the house was influenced by the move away from open communal living towards more privacy for the lord and his family, a progressive change which was not complete until the 18th century. The open hall, with a scattering of lesser buildings which was common in the 13th century, had evolved by the 16th into a main house composed of a number of rooms, with service buildings and lodgings physically attached to it. The increasing size of the household also demanded more rooms, with the senior servants of the lord often receiving their own private lodgings. In many open sites where there were no existing military structures, the main building which was usually an open hall with private rooms at one end (the solar) and service rooms at the other would stand on one side of the main courtyard facing the gatehouse. A chapel and, in some cases, further private chambers, would run along the side nearest the lord’s end of the hall, with guest and household accommodation, a brew house (beer was an everyday drink, even consumed at breakfast), stables and a free-standing kitchen (due to the fire risk it posed) making up the rest of the complex.

FIG 1.4. HAMPTON COURT, SURREY: A medieval country house complex was usually set around a courtyard, with an imposing gatehouse across the entrance, as in this palatial royal building with an oriel window and coat of arms above the doorway.

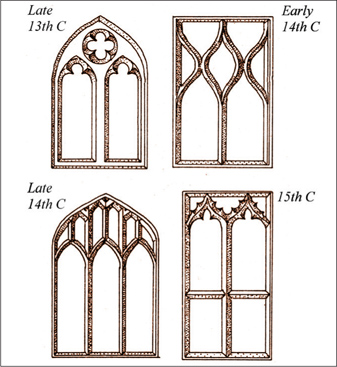

Exterior Details

FIG 1.5: Most windows were simple and square-headed, with vertical supports called mullions and in taller versions with a horizontal bar called a transom. Important rooms like the end of the hall, however, where the lord of the manor sat (the dais), required something more dramatic and windows with tracery (mirroring the styles on churches) were sometimes fitted. The design of these varied through the period as shown with these examples and can help date the feature. Originally most windows were open to the elements (the word is derived from the Saxon ‘wind eye’ and their primary purpose was originally ventilation), with only wooden shutters, animal hide or oiled cloth curtains to close them off. Glass was a luxury item which only became common in the finest houses from the 15th century and was of such value that the whole window frame was often taken with the owners as they moved between properties, until the late 16th century when the windows became a fixed part of the house by law.

FIG 1.6: One place where glass, often decorated with heraldic symbols, could be used to full effect was in an oriel or a bay window. The oriel by the 16th century usually refers to a projecting window from an upper storey although, earlier, the word ‘oriole’ was applied to porches, staircases and a protrusion into an oratory (from which the word oriel probably evolved). A bay window is one which rests on the ground and runs up more than one storey of the house, although you sometimes find this kind of window still referred to as an oriel. They were most strikingly featured at the dais end of the hall, often replacing a tracery opening as the fashionable window for this position during the 15th century. Not only did they allow more light in than a conventional opening permitted but also allowed those in the hall to peek out and see who was at the door!

FIG 1.7: Important entrances would have had a stone- or timber-carved arch, in early examples with a distinct point, but as the centuries progressed it became flatter until, by the 16th century, it appears almost straight. The top corners (spandrels) were often filled with decorative carving and heraldic shields, as in this example from Compton Wynyates, Warwickshire, while the moulding along the top continued down the sides (the jambs) finishing short of the bottom in a patterned piece called a stop. Away from the main entrances, door frames were usually part of the structure of the wall and had the door closing onto the back of them and not inset within. The doors themselves were composed of just a few vertical planks often of irregular width held together by horizontal battens across the back (ones with numerous regular timbers are often later replacements). This simple plank and batten door could be enhanced with decorative metal strap hinges, the nails which held it together formed into patterns, or additional pieces of timber added to create a design or to give the door extra strength.

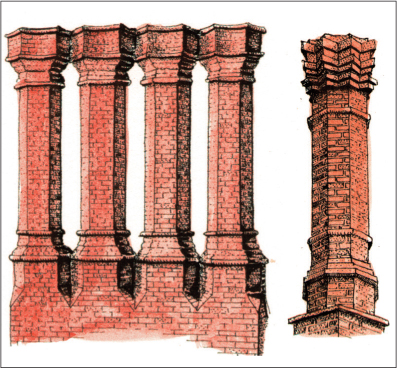

FIG 1.8: BUTTRESSES: The problem which faced masons was that a sloping roof pushes the walls below it outwards. To counter this, buttresses were placed along the side of the building in line with the roof trusses (the triangular arrangement of beams which support it). These grew deeper through this period and, as builders realised that they were carrying most of the load, the walls could be made thinner and be pierced by larger windows with flatter arches. In the above example the buttresses along the side of the hall (top) line up with the main trusses inside (bottom), although the buttresses are a later addition.

FIG 1.9: The dramatic changes to the country house with the creation of private apartments and rooms during the 15th and 16th centuries were only possible in part with the introduction of the chimney (in this period the whole fireplace and stack were called the chimney). Previously, smoke from the fire in the centre of the hall escaped through a louvre opening in the roof which meant there could be no floors above. Despite the use of smoke hoods and bays which set the fire into a corner or end of the room, it was not until the fireplace was positioned against or within a side wall that additional chambers could be fitted above. As smoke from these would be emitted at the lowest part of the roof, a chimney was needed to extend just above the ridge to create a draw. These chimneys became a status symbol, with banks of tall, decorated, polygonal-shaped brick stacks becoming a distinctive feature of Tudor country houses. (Some chimneys were actually false to make it appear the owner had more fireplaces than he did.)

FIG 1.10: EXEMPLAR HALL c.1400: On our first visit to the imaginary Exemplar Hall the date is 1400 and, after passing by low, timber-framed cottages and a few two-storey houses, you come to the imposing crenellated walls surrounding this manor house. As you turn in and pass under the gatehouse you enter a courtyard surrounded by an array of buildings, with household staff busy crossing between them. The old hall is in front of you, recognisable by its large window and louvre in the roof, while behind it is the kitchen, which is separate from the main building due to its inflammable nature. The impression is of a scattered range of buildings, with the eye drawn to the decorative incidental parts rather than the whole composition. This typical medieval picture had developed slowly through the Middle Ages but in the 16th century things were to change with uncharacteristic speed. The new aristocracy would have different ambitions and motivations, and would use the country house as an expression of these new desires and wealth.