Elizabethan and Jacobean Houses

1560–1660

1560–1660

FIG 2.1: HARDWICK HALL, DERBYSHIRE: This was designed by Robert Smythson, the most famous master mason in the Elizabethan period. Built for Bess of Hardwick from 1591–97, it was radically different from earlier houses with its symmetrical front, roof hidden behind a parapet and a greater area of glass than wall. This outward looking mansion was built to impress, with the owner’s initials crowning the dominant towers (‘E.S.’ stands for Bess’s full name, Elizabeth Shrewsbury).

While our aristocratic families were squabbling over the Crown during the 15th century, far away in Italy a new system of education based upon the study of the Humanities (grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry and moral philosophy) led to a new appreciation of Classical Greek and Roman literature, art, and architecture, a rebirth better known to us as the Renaissance. The effect of this upon 16th-century England was limited, mainly due to the break from Rome and Catholic Europe, which resulted from Henry VIII’s quest for a divorce from Catherine of Aragon. Despite this cultural isolation, humanist teachings influenced the upper classes with the new Renaissance gentleman being expected to know Latin and Greek, to have read the scriptures and classics, and to be able to write poetry; while humanist ideals made the acquisition and display of personal wealth more acceptable.

After generations of warfare and plague, the late 16th century marks an upturn in fortunes and no more so than for the gentry. Many aristocrats gained positions of power and influence at Court and increased their wealth by better utilising their estates, perhaps by extracting mineral deposits or enclosing fields, while all benefited from increasing rents and food prices. Many gained new estates after the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the late 1530s although it was not until the relative peace and prosperity under Elizabeth I that the new owners finally knocked down the old monastic buildings and erected dazzling new houses in their place. The ranks of the upper classes were also being swelled by a new class of lesser gentry, courtiers, merchants, and lawyers, who with a good education and by seizing opportunities had risen to high office.

The coming to the throne in 1603 of James I saw the end of hostilities with Spain and made Europe accessible once again, so that Renaissance ideas could flow more freely from the Continent. During this Jacobean age (from Jacobus, the Latin for ‘James’) there were exponents of Classical architecture but their influence on the country house was not to blossom until after the disruption of the Civil War and the Commonwealth. In this period it is the aristocrat or gentleman, armed with an architectural pattern book from the Continent and a master mason, who were the builders of country houses.

The Style of Houses

The first significant change with the new country houses of the Elizabethan period was that they started to look outwards. Although many were still built around a courtyard, they now had a front designed to impress and one which would demonstrate the owner’s good taste and wealth. These new houses were also symmetrical, a Renaissance practice derived from the Ancients’ belief that as the Gods had made us in the image of themselves so the proportions of the human body were therefore divine, and this included the fact that we, as humans, are symmetrical. Although English builders applied this rule and used numerous classical motifs, they clumsily stacked columns and pediments without having an understanding of the true nature of the rules of proportion and geometry which were being used by designers in Italy.

FIG 2.2: BURGHLEY HOUSE, LINCOLNSHIRE: Although it appears as a solid mass, this huge prodigy house built for William Cecil over 30 years up to the 1580s is actually a square ring, set around a central courtyard. Numerous windows, prominent displays of chimneys, and ogee-shaped capped towers are typical Elizabethan features.

Another distinction of this period is the obsession with glass. Now that it was more readily available, the country house builder would seemingly use it at every opportunity. The solid mass of medieval walls was replaced by shimmering façades of tall windows. Brick, which was becoming more widespread across the south, east and the Midlands, was still a luxury product and often featured diamond patterns formed of a different colour. Another distinct feature of Elizabethan and Jacobean walls was the use of a continuous entablature or string moulding, a projecting horizontal trim which ran all around the house at the various floor levels.

FIG 2.3: WOLLATON HALL, NOTTINGHAM: This prodigy house, designed by Robert Smythson, has a raised central section with round corner turrets standing above the hall and creates an outline resembling a castle.

Prodigy Houses

There was no one dominant style in this period. Many lords built timber-framed structures which were still vernacular but now had a wealth of glass and a few token classical details. However, some of the wealthiest and more cosmopolitan introduced imposing new symmetrical houses in stone and brick. These still resembled castles, having corner towers and gatehouses, but now they had large, vertical, glazed windows, carved classical features and decorative parapets, with strapwork patterns or lettering. These large country houses, usually erected with a visit from the monarch in mind, have been christened Prodigy Houses.

Contacts with our Protestant allies in the Low Countries had already seen the import of details like Dutch gables but in the early 17th century as the restrictions on travel to the Continent were receding, Renaissance ideas flowed more freely. By this stage the architects in Europe had long become bored by the limitations of the strict Classical rules and had started bending them. This more playful style, labelled as Artisan Mannerism in England, started to bear fruit in the reign of Charles I, only for the Civil War to cut it short. The first great English architect, Inigo Jones, set to work during this Jacobean period but despite his ground-breaking understanding of the principals of Classical architecture, the limited purse strings of the monarchy meant few of his plans ever made it past the drawing board. Inigo Jones’s genius would have to wait a hundred years before influencing our country houses.

FIG 2.4: Some owners just updated their earlier house (left) by adding new wings (A), fitting a porch (B) to balance the bay window (C) and inserting a chamber above the hall (D). However, when building from scratch (right) the builder could site the porch centrally (E), with the hall in this case to the left (F), the service rooms to the right or rear (G) and an attic floor (H) for extra accommodation.

The Layout of the House

Well-educated Elizabethans loved to communicate in a secret language of symbols and hidden meanings which could even extend to the plan of a house. The E-shaped layout could have implied homage to Queen Elizabeth or to Emmanuel, while the designer John Thorpe even planned a house in the shape of his own initials. Geometric shapes, especially circles, triangles and crosses, could form the basis of the layout. For instance, the triangular lodge at Rushton in Northamptonshire represented the Trinity and symbolised the owner’s Catholic faith. In general, an E- or H-shaped plan was common in this period, formed from wings at right angles to the main body which increasingly had a central porch, while the largest houses appear as a massive block but were usually only one main room deep and arranged around a central open area.

The change of role of the country house from the communal centre of a manor to the private residence of a cultured noble can be seen in the layout of both Elizabethan and Jacobean houses. In earlier examples the hall dominated the main part of the house but as it was entered from one end, the main entrance was sited off centre. As the appreciation of symmetry grew and the hall fell from importance, the room could be re-sited and a central porch positioned in the middle of the façade. At Hardwick (Fig 2.1), for the first time, the hall was turned round end on to the front, making symmetry easier and thus it became the entrance room with which we associate it today.

FIG 2.5: LONGLEAT HOUSE, WILTSHIRE: This was probably the closest that 16th-century England got to a Renaissance house, with its façade a mass of glass, a parapet hiding the roof (A) and a horizontal moulding called a string course (B) and (C) running around the house at each floor level.

FIG 2.6: BLICKLING HALL, NORFOLK: Towers with ogee-shaped caps, Dutch gables (the three in the middle section comprising quadrants and corners) and, on the roof, a white cupola were all popular features in the early 17th century. The tallest windows mark the state apartments which were now often raised above the ground floor as in this example.

With this move to privacy, an ever-increasing ensemble of rooms evolved which could be spread over three rather than two floors. In larger houses there could be a series of state apartments on an upper floor for entertaining and impressing important and, preferably, royal guests. These are usually discernible from the exterior by the row of highest windows. There would then be further private apartments for the family, while the staff still ate in the old hall until as this became an entrance area in the 17th century, a separate servants’ hall was provided. The kitchen could now be found within the body of the building since stone and brick fireplaces set within the wall had replaced open hearths for cooking and thus the fire risk was greatly reduced. A fashionable accessory to any aspiring lord’s house which is almost exclusive to this period is the long gallery. This was a thin rectangular room which usually spanned the entire length or width of the house, with a bank of windows on one or occasionally both sides.

FIG 2.7: A cut-away view of a modest country house from this period, showing a popular arrangement with the hall on the opposite side of the entrance from the service rooms. The long gallery runs along one of the wings though it could also be found along the length of the house, on the second or third floors.

FIG 2.8: HATFIELD HOUSE, HERTFORDSHIRE: There is a distinct Renaissance feel to the central section of the south front of this Jacobean house. The arched openings along the ground floor (known as a loggia), the Classical columns and pilasters, and the Dutch gables are all features copied from houses of the period on the Continent. The pairs of columns up the sides of the central porch are typical of the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

FIG 2.9: A typical 16th/early 17th-century window from a country house. The windows were almost exclusively square or rectangular frames, with a number of fixed horizontal (transoms) and vertical bars (mullions). As there was not the technology yet to make large pieces of glass, the windows were filled with small panes held in place by lead strips in a diamond pattern with metal stanchions up the centre on the inside to prevent damage.

FIG 2.10: The chimneys in this period tended to have individual stacks for each fireplace below them joined at the top, and were often found in rows like this example. Brick and stone were used for their construction, often with prominent bands linking them at the top. By the 17th century they began to become less prominent.

FIG 2.11: This corner tower is a common feature of 16th- and early 17th-century houses. Of brick construction, with stone corner blocks (quoins) and a cap in a distinctive ‘S’ profile (ogee).

FIG 2.12: The humble entrance to the medieval house was superseded in this period by flamboyant, if sometimes clumsy, porches. They are discernible by their height and narrowness, and by the stacked series of Classical ornaments and columns with a round headed doorway below. This example on the north front of Lyme Park, Cheshire, incorporates all these features although the top section with the statue was added at a later date.

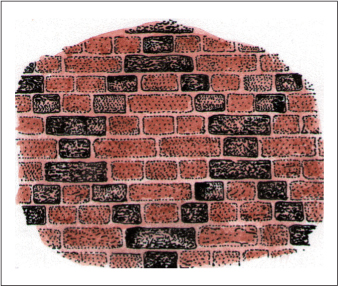

FIG 2.13: Brickwork with a ‘diaper’ pattern made from darker bricks which were vitrified by over burning or the addition of salt in the firing stage of their construction. Bricks of this period were often hand-made on site and were usually thinner and longer than modern machine-made examples. The pattern formed on the face of the wall by the differing arrangements of bricks is known as bonding and, in this period, English bond which was formed from alternate layers of headers (the short end of the brick) and stretchers (the long side) was popular.

FIG 2.14: The parapet along the top of walls hid the roof from view and gave the building a more imposing, Classical form. In this period many were punctuated with initials (as in the top of the towers at Hardwick in Fig 2.1) or, as in this case, with actual words made out of stone.

FIG 2.15: This pattern of swirls and straights formed by flat pieces of masonry slightly raised above the surrounding stone wall is known as strapwork. It was popular between 1580 and 1620, and can be found decorating both exterior and interior features.

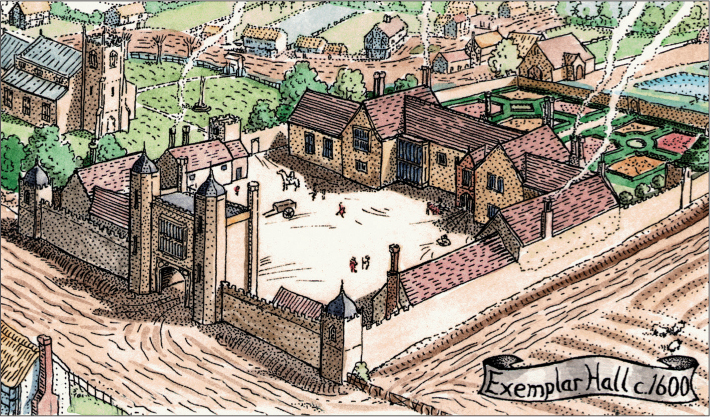

FIG 2.16: EXEMPLAR HALL c.1600: Two hundred years have passed since we last visited Exemplar Hall and the recent lords of the manor have made modest progress and have embellished their family home rather than rebuilding it. The entrance is marked by an impressive brick gatehouse, with the courtyard beyond now lined with new lodgings and service buildings. A small concession to symmetry appears on the front of the main hall which has a large bay window to the left and a tall porch balancing it to the right. A new kitchen has been built on the right side of the house and the area at the rear, where it previously stood, has now become a garden.

Modest country houses like this for the gentry were still amateur attempts at architecture, a sometimes clumsy mix of traditional English forms, with the latest in foreign Classical decoration. From the 1660s a new breed of aristocrat and artisan, better acquainted with the theory and styles of European architecture, was to design new forms of houses with bold, deep structures and carefully planned layouts which would now be emulated by the lesser gentry.