Restoration and William and Mary Houses

1660–1720

1660–1720

FIG 3.1: BELTON HOUSE, LINCOLNSHIRE: This late 17th-century house is similar to Clarendon House in London, by Roger Pratt which, along with Coleshill in Berkshire, influenced the design of numerous country houses in this period. Belton was built rapidly between 1684 and 1687. Surprisingly, its mentor Clarendon House only lasted seventeen years, being demolished the year before Belton was started.

Religious and constitutional differences erupted into civil war in 1642 and, after the subsequent Parliamentary victory, a large number of aristocrats and gentry lay dead or had fled abroad to France and the Low Countries, only returning from exile when the Monarchy was restored in 1660. The population welcomed Charles II but Parliament was more cautious and limited his powers and purse strings, hence he relied on the French King Louis XIV for financial support.

In a period of religious tensions with the Puritans at one end of the spectrum and the Papists (Roman Catholics) at the other, Charles trod a careful diplomatic line, only revealing his true faith on his deathbed. Although he had kept his Catholic leanings secret, his brother James II who succeeded him in 1685 did not, and the birth of James’s son was one of the triggers which inspired a group of lords to invite the Protestant William of Orange, the husband of Charles II’s daughter Mary, to invade and claim the throne. The subsequent constitutional changes known as the Glorious Revolution increased parliamentary powers and gave the aristocracy supremacy over the monarch. As a result, they gained the opportunity to further their wealth, especially with perks from their new positions of office. With its new powers, Parliament had regular sittings rather than just being recalled by the monarch when money was needed. Thus, a social season developed when the gentry and their entourage invaded London, many leaving their country houses during the winter to rent new fashionable urban properties. Some aristocrats, however, went in the other direction, making additional income by putting tenants in their London homes and concentrating efforts on developing their country estates now there was sufficient political stability to give them confidence to build on a large scale.

FIG 3.2: SUDBURY HALL, DERBYSHIRE: A house primarily of the 1660s and 70s which looks backwards as much as forward. Despite the fashionable features on this south front like the cupola, parapet, dormer windows and plain rectangular chimneys, it has by this time outdated details like diaper-patterned brickwork and Jacobean-style mullioned windows. This may be due to the tastes of the owner, George Vernon, who, like some at the time, still acted as his own architect.

This was also the period of commercial revolution and many of the upper classes grew rich on foreign enterprise. Science also blossomed, heightened by a desire to understand and control Nature in the face of what many believed was the impending ‘end of the world’. The gulf between the cultured gentleman, with his new scientific learning, and his illiterate house hold staff, still influenced by medieval superstitions, widened further. The building of the house within which they all resided was still likely to be the project of the owner, but now he was aided by an architect, not necessarily a full-time professional but an educated gentleman who may have studied the fashionable building styles on the Continent and grasped the principles of Classical architecture. They were rarely educated in this art. John Vanbrugh, for instance, had been a captain in the Marines, while Christopher Wren practised anatomy, yet these men of ingenuity replaced masons and carpenters as the designers of country houses.

The Style of House

The returning monarch and his court in 1660 brought with them from France and the Low Countries, a taste for the latest in Classical architecture, new designs which dominated this period such that few gentlemen would consider building their manor houses in a vernacular style. The most distinctive type of country house in this period evolved from the work of Inigo Jones, what little there was, from Coleshill in Berkshire, built in the early 1650s by Sir Roger Pratt (but now demolished), and from the Dutch Palladian-style of houses which was seen by those exiled in Holland. These had a plain façade with quoins (raised corner stones), two rows of tall but roughly equal-sized windows and a deep overhanging white cornice. Above this was a prominent hipped roof, broken up by lines of dormer windows, stout rectangular chimneys, and often crowned by a cupola (see Fig 3.3).

Baroque

Many architectural styles have their name coined by the next generation of designers as an insult to what they regard as an outdated or inappropriate fashion. In this case, later critics labelled the largest buildings of the late 17th and early 18th centuries with their fanciful shapes, opulent decoration and irregular skyline, Baroque, after the French word barocco, meaning ‘a misshaped pearl’. This style had its origins in the 16th-century reforms of the Catholic Church in reaction to the threat from Protestantism in which a new form of art evolved which was designed to stupefy and impress upon the viewer the everlasting and unchanging nature of Heaven. A good example of this change can be seen in portraits: from the rather flat Elizabethan gentleman standing upright with his hand on hip, to Van Dyke’s portrait of Charles I on his bucking horse produced only a few decades later, a new dynamic visualisation full of movement with sweeping vistas and flying angels. This change would also be mirrored in architecture as many aristocrats turned to France for inspiration in creating a dramatic, grand and imposing style of country house.

FIG 3.3: UPPARK, SUSSEX. The façade of this Dutch-style house is capped by a hipped roof (A), with plain rectangular chimneys (B), and dormer windows (C), a pediment (D) and a deep cornice (E). The lower of the two rows of tall windows (F) are slightly higher, indicating that this floor contains the principal rooms while the half-height windows below (G) illuminate the basement.

FIG 3.4: CASTLE HOWARD, YORKSHIRE: The dome (A) and statues along the parapet (B), along with the variation in height, make a dramatic skyline to this famous Baroque house. The main body of the building in the centre is flanked by two separate wings (C) for the service rooms and (D) originally designed as stables but built for accommodation thirty years later.

The houses built in this style from the late 1600s like Blenheim and Castle Howard were monumental in scale, with façades which step or curve in and out, and a skyline of pinnacles and towers which owes as much to the medieval castle as to Continental sources. Other houses of this brief English Baroque period may have been, like Chatsworth, a piecemeal reconstruction, or just a re-faced existing building which in either case limited the shape of the structure. It is in the detailing of the façade where the style shines through. Entrances flanked by oversized blocks, tall windows some with rounded tops, heavy surrounds to openings in the wall, and a stone balustrade along the roof featuring Classical urns or statues (hiding the now lower chimneys) are some of the popular features.

FIG 3.5: BLENHEIM PALACE, OXFORDSHIRE: The central body of this monumental Baroque house was designed primarily by John Vanbrugh. Note the tall windows, now with glazing bars rather than transoms and mullions, the arched heads to those on the top row and the round windows along the basement. Giant pilasters (columns attached to the wall) and the busy decoration of the portico (the pediment supported on columns across the entrance) are typical of this period.

The Layout of the House

The major change in the layout of country houses after the Restoration was the adoption of a double pile plan, that is, one which is two rooms deep. By the end of this period it had also became universal to have a basement. The advantage of this being that as the social gulf between the gentry and their staff had now widened, it was convenient to place the engine room of the house out of sight, along with its smells and noise. The basement also had a stone or brick vaulted ceiling to reduce the fire risk from the kitchen. As there would have to be some light in these service rooms, a row of low windows was inserted which meant that the rooms could not be built completely below ground. In turn, this meant that the ground floor of the house was raised, thus having the desirable effect of making the entrance, now up a row of exterior steps, more impressive to the visitor. At the top of the house, attic floors were standard in the Dutch-style houses. With their massive sloping roofs, a row of small, wedged-shaped windows called dormers sticking out of the tiles was the only way of lighting these rooms. With accommodation now spread over four floors, the actual ground plan of the house could become more compact. The arrangement of the rooms also changes during the 17th century. Houses like Coleshill still had the state apartments on the first floor and they would be approached up an ever more elaborate staircase, sometimes rising out of the hall itself, relegating it to its present role of a reception room. Access to the rooms from the staircases could now be via corridors rather than through rooms as in previous periods. A spinal one which ran the full length of the house sandwiched between the front and back rows of rooms was common, reflecting the symmetry of the exterior.

FIG 3.6: CHATSWORTH HOUSE, DERBYSHIRE: William Talman designed this new Baroque-styled south front (top) for the Duke of Devonshire in 1687, with its distinctive giant pilasters and vases along the parapet. By the time the owner came to rebuild the west front (bottom,) he had fallen out with Talman and this was probably the work of the Duke, aided by his masons, with the central pediment containing the coat of arms, a common feature at this time (completed in 1702).

In the later Baroque houses it became usual to have the state apartments on the ground floor so the grand staircase in the hall was no longer required. Instead, the guests walked directly through to the saloon behind and, from here, could turn left or right to access the luxurious withdrawing rooms and bed chambers. It became fashionable to have these rooms laid out one after the other along the rear of the house, with the doorways all in line, an arrangement known as the enfilade, the length of which in this period of processions and ceremonies became something of a status symbol. The larger Baroque houses further emphasised their monumental scale by having separate courtyards to the side of the central house or flanking the entrance area. One would usually contain the service rooms like the kitchen, separated from the dining room to reduce the fire risk and the odours and noise, with the other courtyard usually housing the stables and coach houses.

FIG 3.7: A cut-away view of an imaginary Restoration house which still has the state apartments on the first floor, the family rooms on the ground and the service rooms in the basement.

FIG 3.8: An example of an enfilade. Note that in this Baroque house the principal rooms are on the ground floor so that a huge staircase in the hall is no longer required. Discreetly positioned stairs lead up to the family’s private rooms.

Exterior Details

FIG 3.9: Square-headed doors and windows could be capped with a segmental arch (left) or a triangular pediment resting upon scrolled brackets, with these options often alternated along a façade or on the dormer windows in the roof. Baroque houses would have more imposing doorways with, in this case, the pediment broken by a huge keystone. The horizontal grooves cut into the side pillars are a style of decoration known as rustication; a favourite decoration of the architect John Vanbrugh.

FIG 3.10: A selection of arched and round windows from Baroque houses.

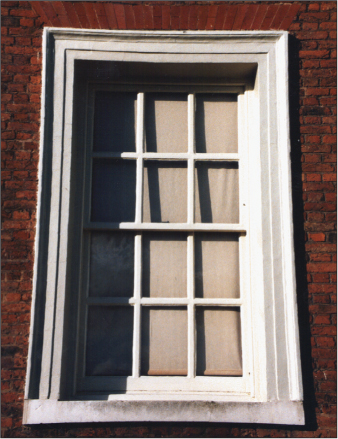

FIG 3.11: From the 1680s, sash windows appear for the first time and quickly become popular. It is hazardous to try and date a country house from the style of window as they were frequently changed at a later date but, in general, the older sash windows have thicker glazing bars and frames, with more numerous lights (the individual opening between the glazing bars).

FIG 3.12: A common feature on Dutch-styled houses was a deep overhanging cornice with carved brackets and moulding. Above this, a row of dormer windows, with alternate triangular and arched pediments, was popular.

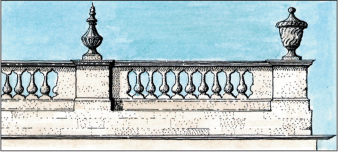

FIG 3.13: A section of parapet which crowned the top of this Baroque house helped to hide the roof and chimneys. The vases standing on top, which could have equally been statues, gave the house a distinctive skyline.

FIG 3.14: Classical scrolls and swags of flowers and fruit were a popular form of decoration inside and out during the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

FIG 3.15: A stone cupola mounted as a central feature on the roof and granting the owner and his guests views over his surrounding parkland. These were usually domed, often with balustrades around the edge of the flat roof on which they stood and were very popular in the second half of the 17th century. Unfortunately, many were later removed along with the balustrades when a house was restyled.

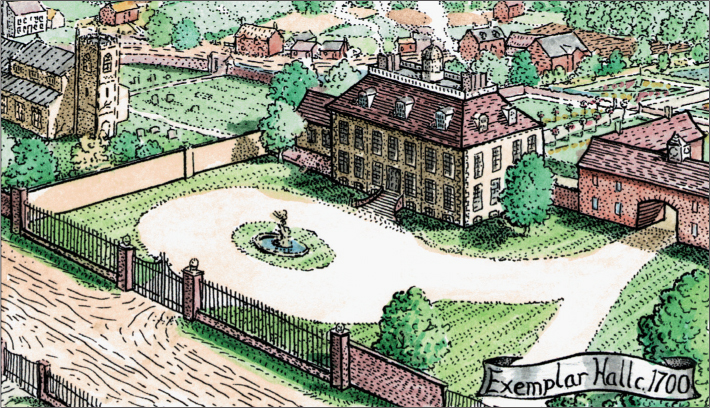

FIG 3.16: EXEMPLAR HALL c.1700: Over the past century the rambling collection of medieval buildings has been swept aside to make way for a new symmetrical Dutch-style house, with only the old chapel and the wall between it and the church retained. To the right the site has expanded out into what were previously fields and a new stable courtyard with an arched entrance has been erected. Behind the house the garden has been terraced and the main estate farm has been masked off by trees and landscaping as the lord of the manor began separating himself from the village both socially and physically. Yet within a generation, this flamboyant style of building would seem outdated and inappropriate and in turn would be replaced by new, strict forms of Classicism and a scale of country house which would result in great upheavals to the communities and landscape around them.