Georgian Houses

1720–1800

1720–1800

FIG 4.1: LYME PARK, CHESHIRE: The south front of this Tudor mansion was designed in the 1720s by Giacomo Leoni in the new Palladian style, with rusticated masonry along the lower section, tall windows on the first floor illuminating the piano nobile, and a portico in the centre capped off by a plain triangular pediment. The pilasters, though, could have been found on Baroque houses.

Those who had supported the exclusion of James II from the Crown and had welcomed the subsequent Glorious Revolution in 1688 had risen in power. In 1715, after the accession to the throne of George I, they removed great swathes of the old landed gentry from high office. These Whigs (from the word Whiggamore, a term for Scottish Covenanters who had also opposed James II) were to dominate the developing political map during the 18th century, excluding the Tories (from the word toriadhe, which was Irish for an outlaw, an insult aimed at supporters of James II) from office until the accession of George III. It was these aristocrats in high office rather than the reclusive Hanoverian monarchs who were the cultural leaders of their day.

The Whigs under Robert Walpole, the first so-called Prime Minister, claimed to be champions of commerce and investment, fighting for liberty as opposed to tyrannical rule. They imagined themselves as senators in Imperial Rome, complete with toga and olive crown, rather than just country gentlemen. They sent their sons off on grand tours of Italy where they not only soaked up the wonders of Ancient Rome but also brought cart loads of it back with them, often one of the reasons for the family country house being extended. The 18th-century aristocrat thus developed from a collector of curiosities into an art connoisseur, amassing books and prints rather than displays of arms. He joined societies devoted perhaps to ancient architecture or archaeology, and opened his mind to emotions and an appreciation of the beauty and drama to be found in nature. In other words it became acceptable to be a bit of a sensitive chap.

This lifestyle did not come cheap, and these gentlemen would benefit from some understanding of developments in science, industry and agriculture to increase their incomes, especially from their country estates which, for many, were their main financial source. Improvement was the order of the day and enclosure of the fields on their land was one of the most controversial and still visible marks that it made. The new houses they built and the older ones which were extended were only possible because of their growing wealth and status. The old Tory squires and repressed Catholic families, however, deprived of the incomes which came with holding office, often had to make do with their old compact Tudor and Jacobean piles.

In the second half of the 18th century, with the defeat of France in 1763 and London now the chief financial centre, there were many commercial gains to be made. Aristocratic sons set off for adventure on the high seas, took up posts abroad, developed quarries, mines and factories and established trading companies, returning with great wealth to enhance their family’s estates. This period of rapid development was halted by the French Revolution of 1793 and the subsequent war with Napoleon as, for the first time, aristocratic families and the ruling classes felt insecure. Suddenly, liberty and sensibility with their French associations seemed inappropriate.

The Style of Houses

This era is dominated by Classical architecture which by the end of the period was being manipulated by professional rather than amateur architects. Few houses were built in any other style until the last decades of the century, and the Ancients’ rules of proportion and architectural orders even filtered down to terraced houses. To the refined Georgian aristocrat, good taste was of primary importance, and his country house would reflect this in its reserved and strict adherence to these Classical rules and orders. Only later in the period would it become acceptable again to bend the rules as Baroque architects had previously done.

FIG 4.2: CHISWICK HOUSE, LONDON: This startling villa was designed by the Earl of Burlington from 1723–29. He promoted the architecture of Palladio and its later interpretation by Inigo Jones and statues of the two men stand at the base of the stairs (just out of view). The plan of the house is square with a symmetrical layout of rooms, aesthetically pleasing but not so practical for everyday use.

Palladian

In the opening years of the reign of George I, a dramatically new style of house started to appear across the country, one which was principally used by, and has since been associated with, the new Whig aristocrats. This style was championed by two men: Colen Campbell and Lord Burlington, who were determined to remove the flamboyant excesses of the Baroque and return to pure Classical architecture as determined by the Roman Vitruvius and the later Renaissance architects. They helped rediscover the drawings and work of Inigo Jones and championed the plans of the late 16th-century Italian architect Andraes Palladio, after whom this new Palladian style was named.

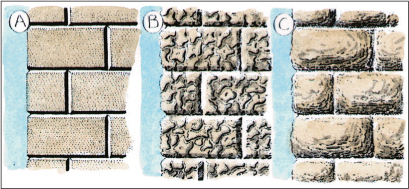

The first influential building in this new style was Wanstead House, London, (demolished 1824) by Colen Campbell. It introduced the characteristic Palladian façade, with a rusticated masonry base (stonework with deep grooves or rough surface) below the first floor or piano nobile, which housed the state apartments and was identified by a long line of tall rectangular windows with smaller ones above. A shallow pitched roof either overhanging with a decorative cornice or hidden behind a plain parapet finished the top of the wall, while chimneys, now that most houses had them, became nothing to show off so were low and kept out of view. Most significant was the portico, a huge triangular pediment supported on columns, which acted as an enormous storm porch marking the main entrance to the house which was reached up a grand staircase from below. Gone were the flowing, undulating lines of the Baroque mansions; now, plain, refined horizontal blocks with temple-like centre pieces were the order of the day for the gentleman of taste. Their beauty lay in the strict adherence to the rules of proportion, with decoration limited to carvings along the cornice and the top of the columns. Palladio had also developed other designs which proved popular – a square plan with porticos on one or all four sides and a central dome above as used at Chiswick House – while a main rectangular block with individual wings linked by a colonnade or corridor inspired buildings like Kedleston Hall in Derbyshire.

FIG 4.3: HOLKHAM HALL, NORFOLK: Rather than the Baroque practice of massing blocks and curves up to a crescendo in the middle, the large Palladian house is composed of separate, symmetrical sections. The main house (A) with a large portico in the middle and a tower at each end is similar to Wilton House in Wiltshire, designed by Inigo Jones nearly 100 years before. The wings (B) at each end are linked to the main house, in this case, by enclosed corridors (C).

FIG 4.4: KEDLESTON HALL, DERBYSHIRE: The main body of the north front, with its distinctive Palladian features of a prominent portico (D) upon a base broken by arches and with stairs (E) either side, a rusticated masonry base (F) and tall first floor windows (G) marking the piano nobile. Further rooms above are distinguished by a row of square windows (H) while the top is finished off with a cornice (I), one of the few areas of decoration on these otherwise plain fronts.

The new generation of architects who appeared in the mid 18th century found strict adherence to Palladio’s pattern book too limiting. They wanted to be more imaginative and creative so they began to look at other periods of history for inspiration, helped along by new archaeological discoveries. Until now, houses were based on Renaissance interpretations or simply on guesses as to what a Roman house would have looked like. For instance, Palladio thought that they all had a portico on the front, so Campbell and his followers in their quest for historic accuracy stuck them on every building. It was only as the societies, which these architects and their patrons helped establish, funded excavations in places like Pompeii that it became clear that, in fact, Roman houses did not have porticos on the front. The new architects increasingly by-passed Palladio’s works and went straight to these new archaeological sources for their inspiration. At the same time Nicholas Revett and James Stuart produced the first accurate drawings of Ancient Greek buildings in Athens and although the limited range of Greek forms did not immediately appeal to architects craving greater variety, they did add Greek orders and detailing to their increasing architectural palette. The country houses which used these newly-discovered Roman and Greek forms from the 1760s onwards are labelled Neo (New) Classical.

FIG 4.5: KEDLESTON HALL, DERBYSHIRE: The south front was completed some years after the north by Robert Adam in a Neo Classical style. Although the sides mirror the earlier work, the centrepiece is based on an actual Roman triumphal arch rather than upon Palladio’s designs. It features Adam’s distinctive shallow and delicate decorative details.

Another difference between Neo Classical houses and the previous Palladian buildings is a return to the more playful use of Ancient architecture. Robert Adams, the most prolific country house architect of this period, believed that the Romans themselves had bent the rules. He set about adding a sense of movement and space to his façades although he despised the Baroque use of flamboyant decoration to hide the function of the building. Features to look out for are curved bay windows, flat domes, columns standing proud of the front and shallow arched recesses. Stone was the must-have material for these new houses (often only a thin cladding) and when it wasn’t available, brick, which had still been accept able in Palladian houses, was covered in stucco, a smooth rendered finish, grooved and coloured to appear like stone.

The Layout of Houses

Throughout the 18th century there was an increased demand for space as aristocrats opened their doors to a wider range of guests, rather than just exclusive dignitaries, and hosted numerous parties. They also had to house all the art works they were bringing back from the Continent and install a library to store their collection of books, as well as setting aside more specialist areas for the production and preparation of food. This wider range of rooms, however, was restricted in size and layout by the Classical orders and symmetry of the façades, while the interior spaces were also controlled by the desire to make them in the correct proportions.

FIG 4.6: SHUGBOROUGH HALL, STAFFORDSHIRE: A Neo Classical façade but with evidence of two previous styles showing through. The three-storey main block was built in the 1690s, onto which wings were added either side in a Palladian style some 50 years later. Samuel Wyatt redesigned it in the 1790s, adding the large, flat-topped portico and a balustrade running at the same level along the façade. This emphasised the horizontal lines which were a key component of a Classical house and held together the various elements from which the front was composed.

FIG 4.7: TATTON PARK, CHESHIRE: This mansion was rebuilt in stages by Samuel and Lewis Wyatt from 1780–1813 in the Neo Classical style. The recessed shallow arches above the outer windows, the swag motifs in the centre and the lack of decoration around the windows are typical features of a house of this date.

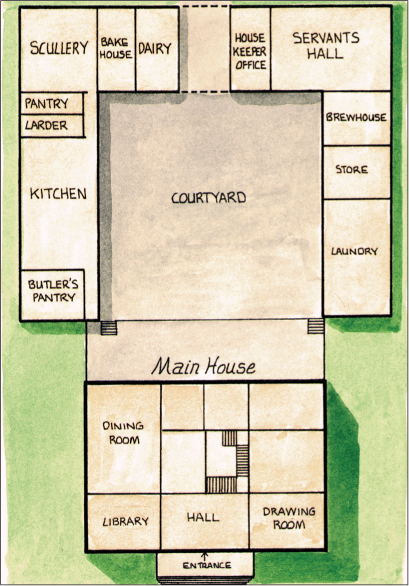

FIG 4.8: Four plans of 18th-century country houses, with the shaded areas showing the possible position of the service rooms: (A) has two wings in line with the front of the house, while (B) has the popular layout for the larger house with four linked pavilions; (C) has the service rooms in a separate building which could be linked by a passage or even a tunnel; while in (D) a courtyard to the north of the house allows the sun to shine on the other three faces of the more compact country house while the working area is cool.

FIG 4.9: A plan of a compact country house from the late Georgian period, with a separate courtyard containing the service rooms. This area often incorporates older parts of the building or masks an earlier front of the main house.

FIG 4.10: A cut-away view of a Palladian house. The hall, with a saloon behind it, forms the axis of the house with, as near as possible, a symmetrical arrangement of rooms off either side. Above these state apartments could be found bed chambers although some further family or guest rooms might be located in one of the pavilions off to the side. The kitchen is in one of these to reduce the fire and odour risk, although some store rooms like the cellar or butler’s pantry would remain in the basement of the main house.

For the larger house a main block with the principal rooms on a raised ground floor could have separate pavilions at each side, connected by corridors or just an open colonnaded passage (a row of columns), with additional accommodation in one and service rooms in the other. Although this impressive design had the advantage of keeping the odours and noises from the kitchen at bay, it was likely that diners in the main house would be receiving their meals cold. Most medium and smaller country houses were still built as a rectangular block, some retaining the 17th-century habit of siting the service rooms in the basement; while others created separate ranges of buildings for them set back to one side or forming a courtyard at the rear of the house. These tended to be closer to the dining room so there would be some heat in the meals by the time they arrived at the table. However, this unwelcome carbuncle growing out of one side would have to be disguised by careful landscaping and planting! The square plan used at Chiswick House, London and Mereworth Castle, Kent was inflexible in its layout and created difficulty in accommodating service rooms especially if the house was to be viewed on all four sides. Thus, this limited its popularity.

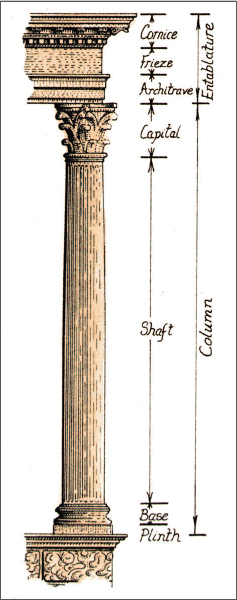

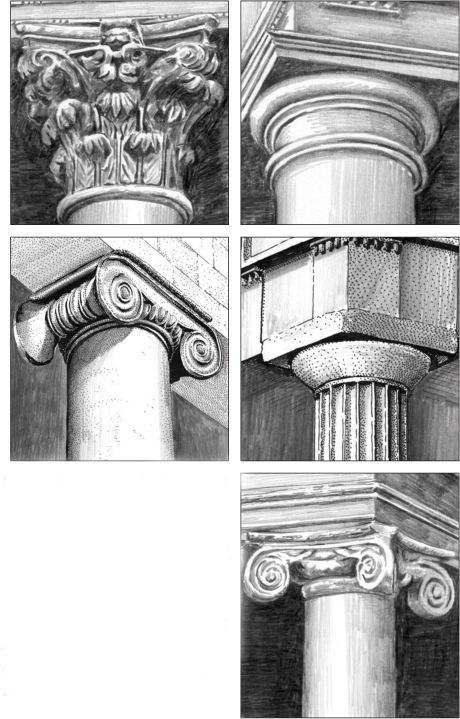

FIG 4.11: A Classical column (in the Corinthian order) listing the parts from which it is composed. Although the various orders had differing proportions and detailing, it is the style of the capital which easily distinguishes one from another. The shaft could be plain or fluted (vertical grooves are shown in this example,) whilst the Tuscan order was always plain.

FIG 4.12: The Corinthian order (top left) was first used by the Greeks but was more popular with the Romans and hence it appears in England from the 16th century. The Ionic order with scrolls was used by the Romans (bottom right) and the Greeks (middle left) and again appears here from the 16th century, while the Composite order incorporates both Corinthian and Ionic. The Roman Doric order (top right) had plain rings and was similar to the Tuscan order, while the Greek version (middle right) had a shallow angled ring directly on a fluted column and as these were recorded from the mid 18th century they became distinctive of Neo Classical houses.

FIG 4.13: Sash windows were almost universal in the 18th century. During this period they have increasingly thinner glazing bars, larger panes of glass, and have their outer frame recessed within and, by the late 18th century, hidden behind the wall.

FIG 4.14: A classic compact Palladian-style house (on the Chatsworth estate), with the distinctive gable end wings and a row of square sashes above the main floors. The tall arched windows flanked by lower rectangular ones in the wings are Venetian and were very popular on Palladian and Neo Classical houses.

FIG 4.15: Rusticated masonry could either be smooth, with chamfered ‘V’-shaped grooves (A), vermiculated with curved channels (B), or cyclopean which is left with a rough hewn finish (C) as if it had been cut out of the very rock the house was built on.

FIG 4.16: Robert Adam is notable as the first architect to really design the whole house from the exterior down to interior details. It formed a distinct style which still carries his name today. His exteriors are distinguished by swags, oval features, round medallions, and Greek decoration, with most mouldings shallow and delicate.

FIG 4.17: Many country houses from the mid 18th century were a bit of a sham with stone cladding as in this example, where it was used to cover up older brickwork or stucco (a type of render) being used to make houses appear more up-to-date.

FIG 4.18: This pavilion from Stowe House, Buckinghamshire, was designed by Robert Adam in 1771. It features shallow blank arches which can cover a number of windows or even a complete front, and decorative garlands and round medallions which were characteristic of houses in the late 18th century and early 19th century.

FIG 4.19: A panel with a garland; in this case, of oak leaves, held by ribbons tied in a bow and a swag which was a common Neo Classical motif.

FIG 4.20: EXEMPLAR HALL c.1800: The owners of Exemplar Hall have made few changes to the main house other than to give it a Classical makeover, fitting a portico on the front and building a new wing to the right to provide extra accommodation. They have dramatically changed its surroundings, however, with the old village cleared out of the way to form a new landscaped garden and the river flooded to make a picturesque lake. Only the old parish church survives and, as it holds the family memorials, it has been rebuilt in a Classical style.

This period of intense building and gardening was to slow down in the last decades of the 18th century due to war, firstly with America and then France. When stability returned there were new gentlemen, who had grown rich on commercial and industrial profit, entering the ranks of the aristocracy, while the search for a suitable national style and influences from an expanding empire combined to change the face of the country house in its last and most glorious period of development.