Panelling, Ceilings and Fireplaces

Panelling, Ceilings and Fireplaces

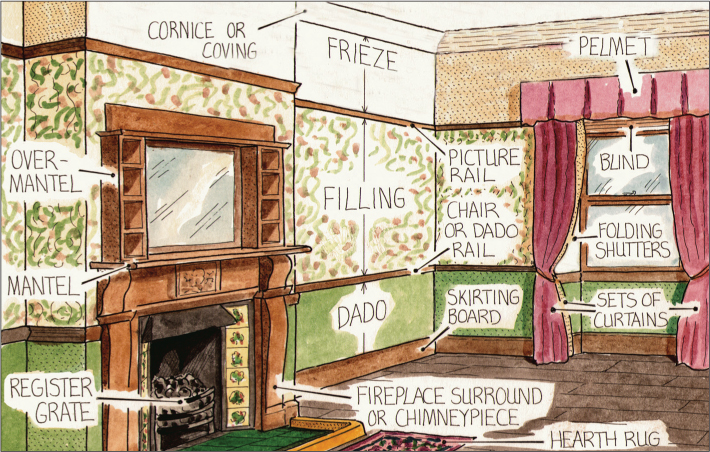

FIG 6.1: A Victorian interior with labels of the key elements of the room which can be found in other periods.

If the exterior of a country house was prone to occasional tinkering by new owners, then the interior was susceptible to what could be regular and complete makeovers. An Elizabethan house might still retain its original façade despite some new trimmings and the odd extension but inside the rooms could be a medley of later Baroque, Rococo, Neo Classical or Victorian Gothic styles. What was once the saloon could now be a picture gallery while a withdrawing room could later house a billiard table. The interior was personal and could be more opulent, exotic and outrageous than the public exterior of the house, with each owner stamping his or her personality and demands upon it. However, underneath these unique and individual features there are some general structural changes and fashionable fixtures which the recognition and dating of can help one to unravel and better understand the development of a country house and how it would have appeared when originally decorated.

Walls

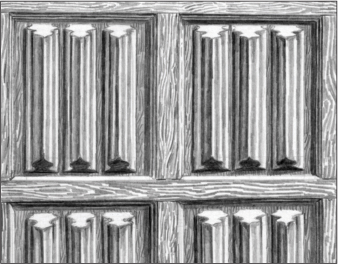

Medieval interiors were not the cold spaces we often see today. Originally they would have been colourful, with whitewashed or painted walls decorated with patterns, text or lines simulating masonry. Wall hangings usually made of cloth painted in strong colours were used to reduce draughts, especially at the lord’s end of the hall. Tapestries were a luxury of the very rich and only appear in country houses from the 14th century. By the Tudor period, wood panelling covering the lower part or complete height of the wall became fashionable. It was composed of frames with moulding around the edges except along the bottom where it was chamfered to make it easier to clean and with square panels inserted. Earlier ones had distinctive linen fold patterns or decorative carvings, whilst later ones were more usually just fielded (raised in the centre with chamfered edges). During the 17th century, the proportions of wooden panelling changed, with each wall of the finest rooms often divided into a lower section (the dado), a main body and then a short upper frieze, decorated with pilasters and classical motifs. In Restoration houses, carving reached breathtaking delicacy in the hands of craftsmen like Grinling Gibbons, with intricate patterns of naturalistic fruits, flowers and swags framing or decorating panels.

FIG 6.2: An example of linen-fold panelling which was popular in the late 15th and early 16th centuries.

FIG 6.3: Small square panels from the late 16th century (top), with moulding around the top and sides (A), a flat chamfer along the bottom (B) and, in the finest examples, strapwork decoration (C). By the late 17th century large panels with classical proportions (bottom) could incorporate panelled doors and bolection moulded fireplaces.

By this time, though, plastering the wall which helped reduce the fire risk was becoming fashionable. The plaster was made from lime or gypsum, often with hair, straw or reed within to give it strength. This was then applied over wooden lathes (thin strips of wood) which had been pinned to the wall. The surface was punctuated by mouldings made from plaster, stucco or even paper maché, which formed classically-proportioned panels, cornices and decorative pieces, with wooden dado rails and skirtings to protect it from the backs of chairs which were positioned around the edge of the room at this date.

FIG 6.4: A section of wall showing how the plaster was applied to the lathes, projecting out of the left-hand side, and then built up in layers before the moulding was applied.

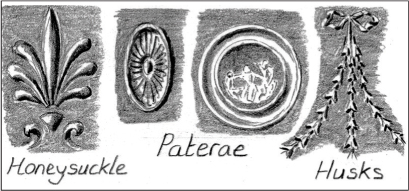

Where decoration was applied, flamboyant Baroque shapes were still acceptable even in later Palladian houses. By the mid 18th century a new variation known as Rococo (from the French word rocaille which described the rocky encrustations which featured on the fashionable grottos of the time) was popular. This was distinguished by deep, flamboyant, naturalistic forms like shells set in asymmetrical patterns and often painted in white and gold. In the second half of the 18th century, architects like Robert Adam, who created his own interior design style, were influenced by new Greek, Roman and Etruscan discoveries, and flatter, more delicate mouldings, with swags, vases, griffins and gold beads decorating panels which were painted in more subdued pastel colours.

Fabrics like silk damasks and leather were used as wall coverings and usually pinned to wooden battens to fix them in place. Wallpapers were first introduced from China in the 17th century though they were not glued to the surface as modern versions are. Flock paper made from left-over wool sprinkled on glued pattern areas of the paper featured in some 18th-century houses while French papers, with exotic scenes or simulated fabric patterns, were still popular into the Victorian period. In later Georgian houses, principal rooms could feature arched recesses or curved alcoves for a statue or have completely round rooms with a dome above based on examples from the Ancient World. Pairs or rows of columns could also be introduced for added grandeur and to control the proportions of a room.

FIG 6.5: Adam-style mouldings and details reflecting the latest Greek taste.

FIG 6.6: Early Georgian wallpapers (top row) copied floral and patterned fabrics, many inspired by Chinese designs. In the Regency period, stripes and Adam-style papers were popular (centre row). By the Victorian era, richly-coloured, three-dimensional papers were common (bottom left); in the second half of the century, lighter, simplified and often two-dimensional designs grew in popularity (bottom right).

By the 19th century it had become fashionable for furniture to be scattered around the room, with tables and chairs arranged in intimate circles rather than up against the sides of the room. As a result, walls with a full height of hanging paper or fabric and without the protective dado rail appear, although the rail and panels still remained acceptable in certain rooms. The more refined and pale patterned papers and fabrics of the Regency home gave way to strong colours and bold designs in the Victorian Gothic home; this in turn giving way to less intrusive two dimensional designs, lighter colours and a revival of oak panelling in later Arts and Crafts houses.

Ceilings

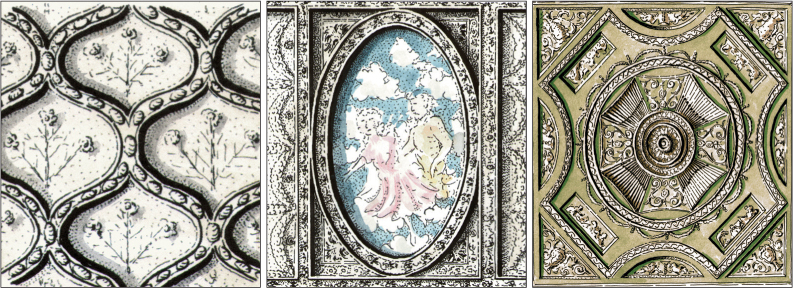

Ceilings did not exist in most medieval halls as the central hearth necessitated the roof being opened to the rafters although the trusses which supported it could be lavishly carved and colourfully decorated. The introduction of the chimney on a side wall permitted the owner to insert a room above and therefore a ceiling which could have exposed moulded beams, joists and decorative bosses at their junctions. Wooden panels were fitted between to make a flush surface which could be painted. By Elizabethan times, a timber roof could be decorated with raised plaster geometric patterns. By the late 17th century, skilled plasterers were creating Classical-style ceilings, with large oval or rectangular centrepieces featuring paintings surrounded by delicate flowers and swags. In Palladian houses, architects endeavoured to create room spaces which would form a single or double cube. As pleasing to the eye as these proportions would have been, the immensely tall walls would have left paintings and decorations too high to be viewed. So, large concave coving (coffered ceilings) were used so they could be displayed in the new lower wall space below. In late 18th-century Adam interiors, the plaster moulding became flatter and more delicate. Pale colours were introduced to highlight the designs, with combinations of pinks and greens, blues and reds, and green, yellow and black often used. Domes and flat barrel-shaped ceilings were also popular with the Neo Classical designers. In the 19th century skylights of iron and glass created new lighting effects, especially over stairwells, while a central flower or medallion moulding from which a chandelier could be hung also became popular; while later Arts and Crafts designers re-introduced beamed ceilings.

FIG 6.7: A beamed ceiling, in effect the main bridging beams and joists supporting the floor above, which, as in this example, could be moulded and have decorative bosses fitted across the junctions.

FIG 6.8: Examples of a late 16th-century plaster ceiling (left) with deep geometric pattern, a late 17th-century one (centre), with a painted scene within the oval, and a late 18th-century one (right), with colour highlighting the shallow plasterwork.

FIG 6.9: A section of Rococo-style ceiling which has been restored to its former glory in white and gold at the parish church which stands alongside Witley Court, Worcestershire.

Floors

The original ground floors of most medieval houses would have been of compounded earth made by raking the surface, flooding it with water and then beating it with paddles when dry. Additives like lime, sand, bone chips, clay and bulls’ blood could also be used for strength or appearance. By the 16th and 17th centuries these rooms could be expected to be covered in stone slabs or perhaps the Dutch fashion of black and white marble tiles. Bricks and clay floor tiles were becoming common in the south and east, with the earliest ones being generally larger and unglazed (glazed versions appear in the 18th century).

In the Georgian period the grandest rooms would have polished stone or marble floors, with brick vaulting below to support the weight now that basements were common. Other floors were composed of boards with early planks wider, or of irregular width, and butted up against each other; thinner regular-sized boards with tongue and grooves only appear in the 19th century. Hardwood boards were polished, cheaper softwood ones painted or grained to appear like a better quality wood, then most of the surface was covered by rugs, carpets or floor cloths. Parquet wood patterns were popular in the early 18th century and were revived again by Arts and Crafts designers.

FIG 6.10: Parquet flooring often laid in a herringbone pattern as in this example was frequently used in earlier houses and was revived by Arts and Crafts designers in the late 19th century.

Carpets first appeared in the 17th century as pieces laid in the centre of the room. Fully-fitted versions made by sewing sections together on site were used in some of the finest rooms from the mid Georgian period but smaller movable pieces which were easier to clean remained common until the 20th century. In the late 18th century as one person increasingly controlled the interior design scheme, an order would be placed for the carpet to be woven into a pattern to match the ceiling design.

In Victorian houses the wider range of architectural styles and greater specialisation of rooms results in a broad range of surfaces from contrasting stone or marble squares to medieval patterned floor tiles. New encaustic tiles with coloured patterns based on medieval designs were popular in Gothic houses, with plain unglazed ones in terracotta, black or buff used in service rooms and areas of heavy use.

Fireplaces

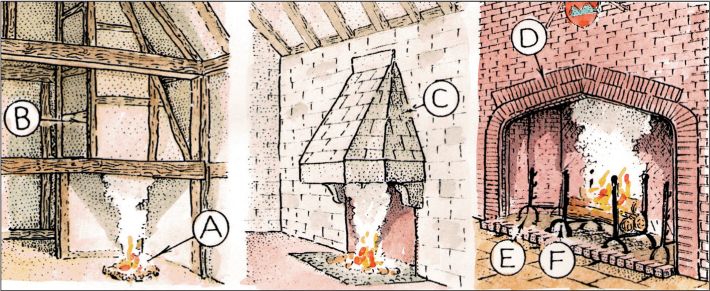

In the great medieval hall, the smoke from the central fire escaped usually through a louvre (French for opening) in the apex of the roof and was often left burning overnight with a pottery colander called a couvre-feu (French for a fire cover from which we get the word curfew) placed over it. The first improvements came with a screen which trapped the smoke from a hearth at one end of the room, or a large hood often made of timber and daub which hung over a fire along the wall, until finally the fireplace and chimney developed. In these early examples, the term ‘chimney’ (derived from the Greek word kaminor meaning ‘oven’) applied to the whole fireplace and stack together. The surround or chimney piece was typically a wide, flat-arched opening in Tudor houses, which was required to fit a large log-burning fire. During the 16th century coal from the north-east (shipped to London and hence known as sea coal) became available to the rich and later fireplaces became smaller as this new fuel could produce the same heat in a more compact lump. Unfortunately for the men who used to climb up the chimney to clean it, these new types were too small, so from this period on, young boys were used.

FIG 6.11: In later medieval halls, the hearth could be moved in a corner (A) and a section above panelled to form a smoke bay (B) to channel the smoke up, while another alternative was a smoke hood (C). By the Tudor period recessed fireplaces behind a four-centred arch (D) or a lintel was fashionable with cob irons (E) which supported the spits on which food was roasted, while the logs were held in place by the fire dogs (F).

FIG 6.12: A late 16th-century, four-centred, arched opening, with a decorative over mantel above.

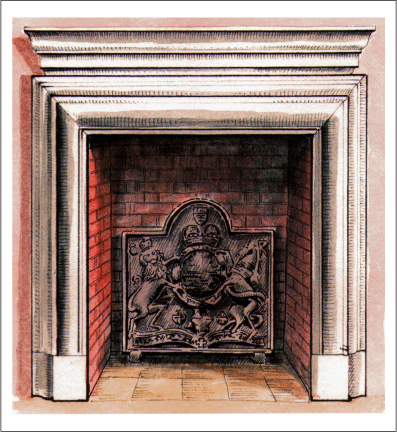

By the late 16th century the fireplace had developed into a principal feature in a room and was lavishly decorated with an ornamental over mantel above it. In the late 17th century a more restrained type of surround with bolection moulding (raised further off the wall near the centre) was set within the panelling. During the 18th century, stone or marble types with a shelf above and Classical columns or figures up the sides were popular, with broader mantels and the latest in Neo Classical motifs in the later Georgian period. By the 19th century, coal was widely available and more efficient register grates with decorative tiles up each side were common from the 1870s. Arts and Crafts architects often preferred log fires and reintroduced them into inglenook fireplaces or created wide surrounds featuring shelving and glass cupboards painted white with bright green and blue tiles.

FIG 6.13: A late 17th-century fireplace surround with distinctive bolection moulding all the way around the opening.

FIG 6.14: A late 18th-century chimney piece designed by Robert Adam. His examples are often distinguished by human figures (caryatids) in place of columns at each side and by a plaque with a raised decorative scene in the middle. Rather than the firedogs which held logs, the now smaller opening features a fire grate which holds coal in a compact block to increase combustion.

FIG 6.15: A distinctive Arts and Crafts-style fireplace with wooden over mantel and surround featuring glass cupboards, shelves and seating.

Doors

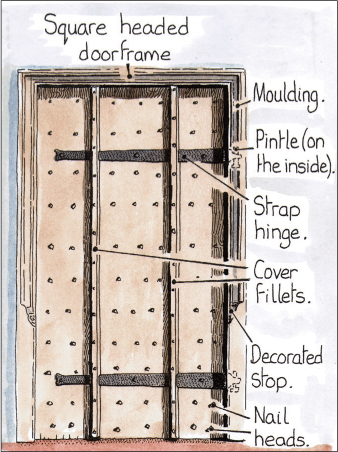

Early doors were made from vertical planks of wood fixed by nails to horizontal beams, and held onto the surround by iron hinges or pins. These and their more decorative variants may have sufficed in a Tudor manor but the Renaissance gentleman and his descendants demanded something to fit in with their classical decoration. Panelled doors thus developed. Early ones had just two panels but by the 18th century the familiar six-panel design was common. Not only were these doors elegant but they were also lighter, so smaller butt hinges could be used which could be concealed out of sight between door and frame. Woods like mahogany and oak were left exposed, but if cheaper softwoods like pine were used they would always be painted. This same rule applied to any other wood panelling or carving in the room. Victorians tended to use four-panelled designs with the later revival of old English styles seeing a return to plank and batten doors with highly decorative iron strap hinges.

FIG 6.16: A late medieval or Tudor door composed of vertical planks with horizontal battens on the other side. These doors closed onto the back of the wall or frame.

FIG 6.17: A Regency six-panelled door, with labels of its parts. The concentric circles or bulls’ eyes in the top corners are distinctive of this period.

After the Restoration, the surrounds which had been part of the structure with moulded and carved sides and tops became lavish door-cases embellished with columns and Baroque decoration with entablatures and a pediment across the top. Sometimes a double set of doors was fitted, usually to help keep food odours out of adjoining rooms; while the famous green baize door which separated the main house from the service rooms had the material pinned to one side to keep offensive noises at bay.

Stairs

The earliest way of ascending to what few upper rooms there were in a medieval house was by stairs which were little more than a sturdy ladder or, in a more impressive stone building, a narrow spiral staircase. As rooms on upper floors gained importance, wider and more elaborate stairs were required to reach them, often in a separate tower or short extension at the rear. By the early 17th century the more familiar closed string staircase was becoming popular, with separate treads and risers running into a side string course which was supported on thick corner and end posts called newels. They were considered a great status symbol and their oak posts and balusters were beautifully decorated, often displaying coats of arms with carvings of beasts and, later, classical figures and naturalistic details. Their importance could be further emphasised by being built in a separate room often at the end of the hall, a few examples still having carved dog gates at the bottom which were used to keep the animals in the hall at night.

FIG 6.18: An early 17th-century closed string staircase, (where the treads and risers run into the side support), with decorative balusters (A) and newel post (B), with a dog gate at the top.

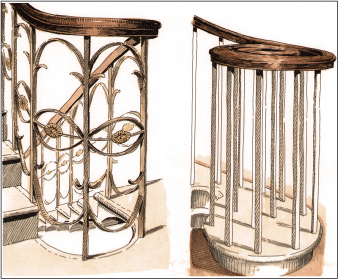

As joinery techniques improved, the newel posts ceased to rest on the floor and the steps appeared to float up the staircase (although they were actually cantilevered off the wall). Some had their now exposed undersides plastered like a ceiling, with decorative mouldings and even pictures; while others had beautiful parquet floors fitted on the landings and elaborate carved posts. During the 18th century staircases have open strings with the now more elegant and thinner balusters (often set in pairs or threes) resting directly on the tread; cast-iron types with mahogany handrails and spiral ends being very distinctive of the later Georgian period. Victorian staircases reflected the style of the house with replicas of a past age common; only Arts and Crafts designers made new inventive forms which heralded in the modern styles of the 20th century.

FIG 6.19: Regency cast-iron balusters which rest upon the treads (open string).

FIG 6.20: A late 17th-century balustrade, with rich wooden carving.