Terraces, Parks and Gatehouses

Terraces, Parks and Gatehouses

FIG 9.1: LAMBETH PALACE, LONDON: The gatehouse was often the most important building after the main hall in a medieval and Tudor country house. It not only displayed the owner’s power and wealth but also housed a senior member of the household in its upper rooms. It is just one of the buildings which can be found today around the main house which were once vital parts of the gardens and estate.

The Gardens

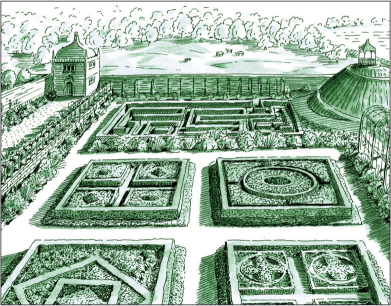

There is evidence that gardens were laid out within the grounds of medieval castles and country houses. Some were small areas for growing herbs and flowers, or for playing games and relaxing, while others were possibly larger in scale. During the 16th and early 17th century, as the country house developed from an inward-looking defensive building to an outgoing display of wealth, gardens became an important part of the design. They were a place of leisure, with games, plays and masques acted out upon their lawns, and contemplative walks taken through flower beds and arbours. Knot gardens, with geometric patterns formed from low box hedging (some designs reflecting the Elizabethans’ love of secret symbols), were popular, as well as sundials, brightly-painted statues and a raised walkway or a large mount for viewing the scheme (look for a grassed-over mound up against the edge of a garden today). Mazes were often laid out although at this date they were formed from low hedges which the viewer could see over; the tall hedged maze, correctly termed a labyrinth, was a later development.

During the Restoration, the returning Royalists brought with them new ideas on gardens from France, with rectangular beds of low hedging containing flowers and coloured gravels called parterres (a French word meaning ‘on the ground’) spread out from the house on a much larger scale than the previous knot gardens. Terraces with balustrades, long rectangular water features with cascades and fountains, and topiary cut into geometric shapes were among the features to be found. With the accession to the throne of William and Mary in 1688, Dutch gardens became fashion able; usually smaller than their French counterparts, with more elaborate detailing, trees in tubs, lead statues and a mania for tulips! Many shrubs were grown purely for their foliage and were known as greens, being brought inside in winter to the greenhouse which, at this date, was a conventional building, often with accommodation above for the gardener. The value of light to plant growth was not appreciated at this date.

FIG 9.2: The rear of an Elizabethan country house, with a knot garden in the foreground, a maze behind that, a banqueting house (rear left) and a mount (rear right) from which the scheme could be admired.

FIG 9.3: POWIS CASTLE, POWYS: A view from the terrace, with its balustrades and statues, over this late 17th-century garden. The plain lawn to the right originally contained parterres, geometric-shaped ponds with fountains, statues and a cascade flowing down from the now densely-wooded wilderness beyond (far right).

The gardens also began to spread out into the estate, with arrangements of high clipped hedges in geometric patterns called a wilderness laid out for walking within, although where this name survives today the area tends to be more appropriately natural and wooded.

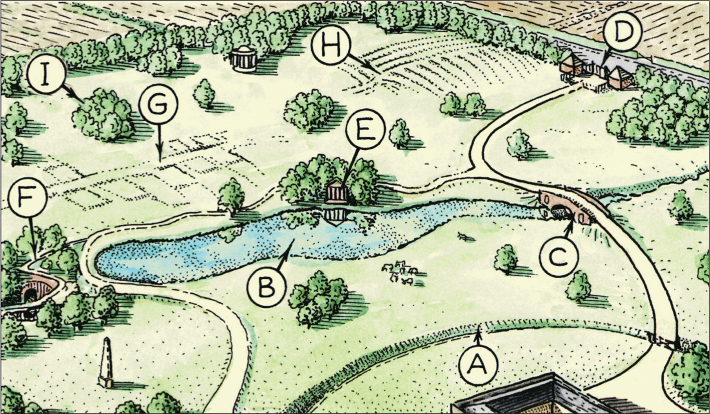

During the 18th century, the landscape garden was developed. It was inspired by 17th-century paintings of classical scenes featuring expanses of lawn, lakes, ruined castles, towers and temples. The garden designers who transferred these images to the English countryside were increasingly professional men, the most famous of whom was Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, who gained the name ‘Capability’ from his habit of informing clients that their gardens had capabilities. In order to create these vast expanses of private parkland, the owner would remove villages and turn over fields. The dispossessed locals may have been housed in a new village, well out of view of the house, but many were simply evicted and moved to the towns to find work in the new factories and mills. The land they left behind was transformed into gently rolling park land, interspersed with clumps of trees and large serpentine lakes (in a long, curving shape like that of a serpent) and bounded by a thick band of trees. Despite these subsequent changes, the faint banks and ditches which marked the original homes and fields can still be seen in many parks today.

FIG 9.4: An aerial view of an 18th-century landscape garden, with labels highlighting some of the features to look out for today. The house is near the bottom right corner and is surrounded by a ha ha (A). In the middle distance is a serpentine lake (B), formed by damming the local stream, which is crossed by a classical-styled bridge (C), carrying the main drive from the similarly treated gate lodges (D). From the drive, visitors can view the various eye-catching buildings, including a mock temple (E) overlooking the lake or wander down to the grotto (F), formed around the waterfall created on the dam. Traces of the old village (G) and the ridge and furrows of the open fields (H) which were moved when the garden was created can still be seen in the form of lumps and bumps in the open grass which is punctuated by clumps or individual mature trees (I).

FIG 9.5: Maps of Nuneham Courtney, south of Oxford, showing the original village (in red) next to the manor house in 1700 and the re-sited settlement a century later built alongside the new turnpike road to make way for the new Nuneham House and its landscape park.

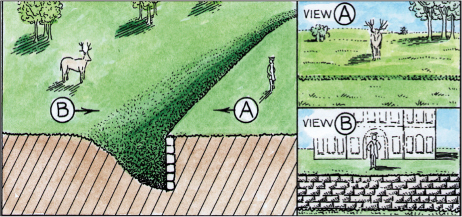

The 17th-century formal garden was designed to be viewed on foot from fixed points, with straight avenues leading the eye into the distance. The landscape garden, however, was to be appreciated by guests arriving in carriages, so clumps of trees and eyecatching follies were arranged so that the view slowly changed to reveal distant objects as visitors were driven along the winding road. With a growing appreciation of nature and the picturesque in the second half of the 18th century, ruined garden features, grottos, shell-lined caves, and furniture and buildings made from bark-covered wood became popular. The park also came right up to the front door although this meant that the deer and livestock could wander up to the house, too. Therefore, a ha ha was devised, (a ditch with a vertical wall one side and a slope the other), to stop the animals getting too close.

FIG 9.6: A section through a ha ha, designed so the owner looking out would see view (A) where the ditch is virtually invisible, giving unbroken views over the park, while the deer looking towards the house would see view (B), with a wall preventing it getting closer to the house.

By the turn of the 19th century the aristocracy were becoming bored with the plain expanses of green. A new breed of designers like Henry Repton reintroduced formal beds of flowers, gravel walkways and terraces around the house, while thicker blocks of trees with greater variety were laid out in the park. These schemes were often smaller than the preceding landscapes so, in order that the owner would appear to have a larger park, eye-catching features were erected on distant higher ground. These remote towers and obelisks can often be found today many miles from the house from which they were intended to be viewed.

FIG 9.7: BIDDULPH GRANGE, STAFFORDSHIRE: A restored Victorian garden laid out in compartments, with differing themes linked by serpentine paths and tunnels, and characterised by exotic trees, rocky outcrops and structures inspired by buildings from around the globe.

Victorian gardens were inspired by a variety of historic and exotic sources but were often compartmentalised. Different areas could be given over to formal planting, water features, scenes from distant lands, or woodland. Priority was given to the content rather than the structure of the design, with plants and trees laid out in such a way that the individual plant would be displayed at its best rather than for any collective effect. Shrubs and trees from all around the globe could now be nurtured in glasshouses before being planted out, especially conifers which, along with rhododendrons, formed distinctive dark barriers around country houses. Some trees and shrubs were planted to make arboretums; if only conifers were grown they were known as pinetums. Rock and wild gardens, shrubberies and ferneries were also popular towards the end of the century.

In the 20th century the expense of running a large team of gardeners proved too much for many owners. Land was either left to grow wild, often becoming overgrown with rhododendrons, or was sold off for farming or building, with the occasional mature tree or garden feature appearing in modern housing estates. Several of those gardens which have survived to the present day have now been restored to their original form or as near as possible to how they might have once appeared.

In the late 17th century there was a fashion for growing orange trees in pots. Orangeries were constructed to protect the trees in winter, with the additional benefit that the buildings could be used for social functions in summer when the pots were placed outside. These early types were often built into a terrace with just a row of windows exposed at the front; later ones were built off a wall or might be free-standing. They were typically brick or stone structures, with a tiled roof and a row of south-facing windows set within a line of archways (a loggia), although some had glass roofs inserted later when they were used to store exotic plants all year round.

Conservatories became a distinctive feature of 19th-century gardens. They were built onto the house, with large metal frames often cast with decorative arches and with vast areas of glass to house plants from around the Empire. Hot water heating systems were used, while heat might also be obtained from a fireplace and flue on the other side of the rear wall. The high maintenance these required meant that many were abandoned or removed in the 20th century.

Follies, monuments and grottos

There have always been garden structures within which to socialize, contemplate or appreciate the surrounding flora. In the 16th and 17th centuries there were banqueting houses where diners could retire after a meal and enjoy sweets (see Fig 7.5), and gazebos or summer houses from which they could admire the owner’s clever garden designs and discuss their hidden meanings. It was in the 18th century, though, that the strange, monumental and exotic structures which we term as follies were built as part of the landscape gardens. They were not as useless as the title implies, though. They acted as eye-catching features and as venues for garden parties, music recitals and social meetings.

FIG 9.8: TATTON PARK, CHESHIRE: This conservatory was designed in 1818 but unlike most later versions, it was a free-standing stone and glass structure and still holds exotic greenery today.

Although the main house had to be built with strict rules and fashions in mind, architects were given a much freer range with garden structures. Some were copies of the round towers which featured in the paintings of artists like Claude which had inspired the landscape garden in the first place. Others were copies of Roman and later Greek temples, triumphant arches and rotundas, pieces of the Ancient World recreated for the owner fresh back from his Grand Tour. Gothic architecture appears on the country estate in the mid 1700s, a generation or two before it would be considered suitable for the main house. With a growing appreciation of nature and all thing British in the late 18th century, sham castles, ruined structures and fake prehistoric stone circles were erected. Another source of inspiration was the exotic Far East, with Chinese pagodas and bridges proving especially popular. Statues and monuments also featured in these park schemes and it is not unusual to find an impressive stone pinnacle erected to the memory of a favourite pet. In the 19th century, compartmentalised garden buildings from a historic period or distant land added the signature to a garden theme.

FIG 9.9: A selection of follies ranging from (clockwise from top left) Classical temples, Egyptian buildings, Chinese pagodas, and Gothick structures (which looked nothing like genuine medieval buildings). These exotic styles were often considered too daring for the main house but were happily used in the garden. The finest collection in their original setting is probably at Stowe Landscape Gardens, Bucks.

Lakes, fountains and bridges

Moats which surrounded late medieval manor houses were probably part display and part fishpond (freshwater fish was a vital food source). Few were ever built to keep an army at bay. In the finest 17th-century gardens, long rectangular ponds, often referred to as canals, were a distinctive feature. Some came with complicated water schemes to supply fountains within them and cascades at the far end. In the 18th century, huge lakes were built as part of landscape gardens. They were usually formed by building a dam across an existing stream and flooding the bottom of the valley. To carry the main road up to the house, ornamental bridges were built. Often designed by leading architects, they were usually beautifully proportioned Classical structures with round or segmental arches, balustrades and niches, and carefully positioned to fit in with the overall scheme.

The Estate

The estate was the foundation upon which all country houses were built. It not only provided the owner with financial income but supplied the house with food, materials and manpower, making it relatively self-sufficient even up to the 20th century. These estates are most likely to have been formed in the general reorganisation of land ownership which took place after the Norman Conquest, although some estate boundaries can date back much further. During the feudal medieval period the majority of them operated as manors, run by the lord (or his tenant in chief if the lord resided at another estate), from a castle or principal house (manor house). The estates would comprise a demesne, land on which the produce grown was for the lord’s table only, which the villagers would have to send a family member to work, as well as supply a certain amount of produce from their own fields. The remainder of the fields were used by the villagers, with decisions on how it would be farmed made at the manor house which, in addition to its role as local court house and close proximity to the parish church, made it the centre of the community.

FIG 9.10: STOWE LANDSCAPE GARDENS, BUCKINGHAMSHIRE: Classical-styled stone bridges were a distinctive feature of landscape gardens and were often designed by leading architects rather than engineers. This Palladian-style bridge was a popular form in the mid 18th century.

FIG 9.11: WITLEY COURT, WORCESTERSHIRE: Fountains could be designed with huge jets of water but none so tall as this restored example. Most were powered by gravity, with a tank or lake on higher ground feeding water down pipes to a small outlet which focused the jet.

Famine and then the Black Death in the 14th century played their part in breaking up this system. Unable to find peasants to farm their fields the lord of the manor granted the land to a new breed of individuals in return for rent. Thus, the feudal peasants slowly became tenant farmers and the gentry became landlords. The manor house would still be fed by produce from its own land, although as the landscape was reorganised by enclosures from the 15th to 19th century a home farm was usually established from which it would be managed. The village which housed the staff working the estate was often moved or rebuilt during the Georgian and Victorian period, principally so that the approach to the house would complement the grand building and also so the owner could keep a tight rein on who lived there.

Stables and Coach Houses

Every country house would have had stables close by in which were housed saddle horses, coach horses and cart horses, together with their foals. Most date from the 17th to the 19th century and are usually found with a large archway featuring a cupola and clock above which leads into a courtyard housing the stables, coach houses, blacksmiths, joiners and a tack room, the latter having a fireplace to keep the leather warm and access up to a hay loft. Coaches had become popular with all levels of the gentry by the late 17th century, and most would have two, a basic one for everyday use and another of greater luxury.

Hunting and Racing

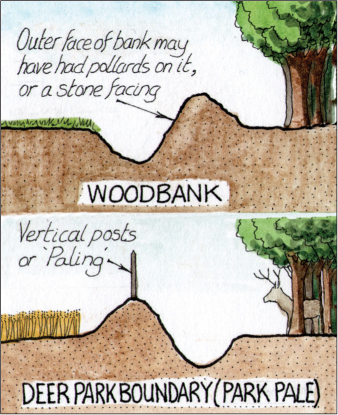

Hunting was the favourite pastime of medieval lords of the manor and most established deer parks near their house in which to contain the animals. These were usually roughly circular enclosures of up to 200 acres surrounded by a ditch and bank, with a fence along the top from which the deer could be released at the time of a hunt. As this form of hunting declined in popularity during the 17th century so the old deer parks were often turned over to agriculture although their distinctive round shape can often still be spotted on maps today.

FIG 9.12: DUNHAM MASSEY, CHESHIRE: This stable block (used as a coach house) with its distinctive white cupola dates from the 1720s and originally contained a brewhouse, a bakehouse and a large space for the carriage horses (riding horses, cart horses and dairy cows were kept in a separate block).

The fox had become the quarry of choice by the 18th century, bringing together all ranks of the estate with the master, usually the lord himself, leading the pack, a huntsman responsible for looking after the hounds and hunt servants to organise the event. Developments in gun making meant that from the late 17th century shooting replaced hawking and by the 19th century had become the preferred sport of the aristocracy.

FIG 9.13: The old ditches surrounding deer parks can sometimes still be found. They differ from those which kept livestock out of old woods which would have a bank on the inside edge (top). Because they were designed to keep the deer within the enclosure, the bank was on the outer edge (bottom). These features will be much reduced in height today.

All these activities would have left some mark on the estate. For instance, there would be kennels for the pack (usually on one of the estate farms) and strips of wooded land often labelled as coverts in which foxes and game birds could be protected before the hunt or shoot. Another popular pastime in the 18th century was horse racing and there may even be a circular or oval track marked on old estate maps.

Home Farms

The fashion for nobles to become involved in agricultural improvement from the 18th century produced a spate of new farm building, featuring the latest technologies. By the mid 19th century, the home farm of the estate had become more like an efficient factory production line rather than a rustic collection of barns. It would ideally be formed around a courtyard, with brick or stone buildings containing some of the earliest farm machines At first these were powered by a horse wheel (look for a round or polygonal structure on the side of the farm in which the animal walked round), a water or wind mill, and later by a steam engine, the chimney of which often survives today. Other buildings on these model farms could have contained cattle stalls, stables, store rooms, poultry houses, cart sheds, and sometimes a dairy. The brewhouse and bakehouse might also be here rather than in the service rooms; often next to each other as the same skilled man was required for both processes. Outside there would be a house for the bailiff, steward or manager, from which an eye could be kept on the farm-hands’ comings and goings.

Dovecotes

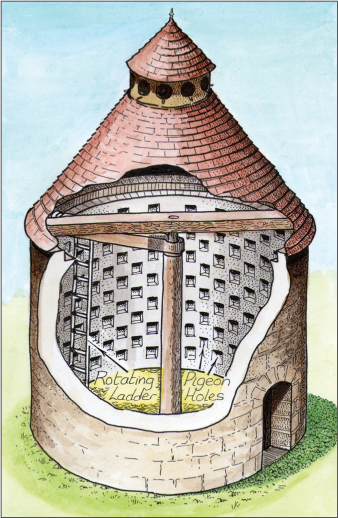

Another essential feature of the estate which provided the owner of the house with a more diverse assortment of food, especially in winter, was the dovecote. This was a round or square structure with a pointed roof and openings in the gables from which the birds could fly out. Inside, the pigeons (doves were not kept as they won’t return home) nested in recesses, with a ladder for servants to gain access to them. Although some early examples do survive, most of those which you will find today date from the 17th to 19th century.

Fishponds and Warrens

A set of ponds in which fish were reared for the lord’s table was an essential feature of any medieval house, usually often in the form of a row of roughly triangular pools tiered one above another. Although most were later abandoned or filled in as sea fish became more widely available, some were incorporated within later garden schemes and their distinctive shape can still be identified or spotted as dried out indentations on the ground. The medieval estate would also provide the house with another delicacy – rabbit – which was introduced by the Normans and bred in purpose-made low banks called warrens.

FIG 9.14: A dovecote, with its distinctive tall form and access for the pigeons in the top.

Churches

Most country houses have a church standing nearby and if the latter building is medieval in origin, then it can indicate that the site has been occupied by a substantial house, in some cases for over a thousand years. It was common for Saxon and Norman nobles to establish a church next to their halls as a status symbol in order to climb the social ladder. This only fell from fashion in the late 12th century, by which time most medieval parish churches had been established. When villages were later re-sited or fell into decline, the church was left behind next to the house, often receiving a Classical makeover or being completely rebuilt to complement the style of house. The Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 also meant that suppressed Catholic nobles could pray openly and fashionable Gothic brick churches appeared on some of their estates.

FIG 9.15: WITLEY COURT, WORCESTERSHIRE: An 18th-century Classical church, with its distinctive rectangular form, semi-circular arched windows and clock tower with cupola, which had replaced an old decaying medieval structure. The rather plain exterior is in stark contrast to the spectacular white and gold Rococo interior which is one of the finest in the country.

The owner of a large country house would usually have a private chapel. He and his family would only attend the parish church on a Sunday when they would expect a private set of pews and even a fireplace so they did not have to suffer the sermon in discomfort. It was also the practice for the church to hold the family monuments, usually in a side chapel or aisle. Even when the noble decided to move his seat to another of his houses, family burials would still take place in the original parish.

Ice Houses

Ice houses were built to keep large quantities of frozen water available all year round. They were insulated pits covered by a brick dome with an air vent to reduce damp (which accelerated melting), with access through a small tunnel with at least two sets of doors to keep the interior cool. The ice would be collected in winter from a lake, pond or canal by estate workers, using hooks, mallets and rammers. It was then dragged along to the ice house where it would be broken up and compacted in the bottom of the pit with straw laid between for insulation. For the ice to last the whole year, the position and construction of the ice house were critical. For convenience, it was usually sited near the source of the ice and built into a slope so that any melt water could flow out of the bottom. It was often surrounded by trees for shade. As you can imagine, the ice collected off the top of the lake could be pretty mucky and was only used to cool bottles or was placed in ice boxes. Only imported ice available from the mid 19th century was of good enough quality to be placed directly into drinks.

FIG 9.16: A section through a 19th-century ice house. Doors set along the tunnel would lead to the pit in which the ice was held, with an iron or wooden grate at the bottom which allowed any melt water to drain off via the pipe while a sandwich of brick, stone, charcoal and clay insulated the interior. All that may be seen today is the gated entrance to a tunnel set in the side of a mound within a wooded area.

Gatehouses and Lodges

Gatehouses were built to strengthen the defences of the entrance to a castle and, later, to walled manor houses. By the 15th century, though, they were more for display than for military reasons. A senior member of the lord’s household would reside in the room above the gate while a porter controlled entry to the courtyard beyond (as is still the case at many ancient universities and colleges today). The last gatehouses were built in the early 17th century. Afterwards, with the boundary of the park moving further away from the house, a pair of lodges either side of the entry to the main drive became the norm. Classically-styled lodges in the 18th century and quaint Gothic or Italianate cottages in the 19th century usually housed an elderly member of staff who, at the sound of a horn or whistle from an approaching coach, would open the gates.

FIG 9.17: STOKESAY CASTLE, SHROPSHIRE: A 16th-century, timber-framed gatehouse, with accommodation above for a senior member of staff.

FIG 9.18: BURTON AGNES HALL, DRIFFIELD, EAST YORKSHIRE: An early 17th-century gatehouse, with distinctive ogee-shaped caps to the towers and odd proportions to the Classical ornaments above the semi-circular arched opening. The hall behind was built from 1601–10 to a design attributed to Robert Smythson, although next to it the original 12th-century hall can still be visited.