The Even Greater Escape

THE SUN CAME up over Oslo and Akershus Fortress. And there was a great commotion there.

“What do you mean,” growled the Commandant, “the gunpowder from Shanghai is missing?”

“It disappeared while we were unloading it onto the wharf yesterday afternoon, sir,” said the steadfast but obviously nervous guardsman in front of him.

“Disappeared? How is that possible?”

“The longshoreman swears it was eaten by a big snake, sir.”

The Commandant’s growl made the window-panes in his office rattle. “Are you trying to convince me that some snake ate the whole crate of gunpowder?”

“No, sir. The longshoreman is trying to convince me of what I’m trying to convince you, sir.”

The Commandant’s face was now so red and his stomach so inflated that the guardsman was afraid he might explode at any moment. “Excuses! That butterfingers dropped the crate in the water! Do you know what this means, my dear cannoneer?”

And the cannoneer knew what it meant. It meant that for the first time in over a hundred years, there wouldn’t be any Royal Salute. People from Strømstad, just across the border in Sweden, to Poland, and yes, even all the way to Madagascar, would scoff at their little country way up north, make fun of them, and call them things that rhyme with Norway. Gorway and borway and sporway and things that might not sound so bad in English, but that could mean really preposterous things in Madagascarian.

“What do we do now?” asked the cannoneer.

And like a big red balloon that suddenly popped, the Commandant sank down into his chair, thumping his forehead against his desk, and then stopped moving. He tried to say something, but his lips were squashed against the top of the desk so it was impossible to understand him.

“Um, what?” asked the cannoneer.

The Commandant raised his head off the desk. “I said, I don’t know.”

BUT THE SUN kept shining and smiling as if nothing had happened. And it really shouldn’t have on a day like this. Because let’s review the situation, dear reader. The Commandant’s gunpowder is missing. Nilly has been eaten. Doctor Proctor is in jail. And his powder has been stolen by the evil Trane family.

So why does Lisa seem both happy and unconcerned as she plays her clarinet and marches down the streets of the city in the Dølgen School Marching Band at the crack of dawn on the day before Independence Day? Could she have forgotten all of their problems? Is she maybe not who we thought she was? Does she actually not care about her friends at all? Or does she know something we don’t?

Perhaps, but we also know something she doesn’t know. We know that Nilly was eaten by an anaconda. And the only other one, aside from us and the snake, who knows that is Nilly himself.

I’VE BEEN EATEN by an anaconda, Nilly thought as he sat there in the darkness inside a snake’s body that was moving and slithering as the ceiling and walls dripped. He was still sore from having been kneaded through the snake’s jaws and throat, but there was more room in here and he was still more or less in one piece. But, of course, that was just a matter of time. Because he knew from page 129 in Animals You Wish Didn’t Exist that the stuff dripping on him was a highly corrosive blend of digestive juices. And that in time it would dissolve Nilly’s body into its individual components. As it had done to the poor thing that had owned the metal collar Nilly had found when he’d wound up in here the night before.

Nilly’d just had time to read the name engraved on the collar before his phosphorescent powder had stopped working. Attila. That was all that was left of the poor thing. The digestive juices had already started eating away at the soles of Nilly’s shoes, and the scent of burning rubber stung his nostrils. There was little doubt that he was facing a slow and rather gruesome death. There was little doubt that his hopes that the constrictor would sneeze or hiccup him back out were dwindling rapidly. There was no doubt that he had to think of something, and he had to do it in a flash.

So Nilly thought of something.

He pulled the envelope of fartonaut powder out of his pocket.

THE CONSTRICTOR ANNA Conda woke up suddenly. It had been dreaming the same dream it always dreamed. That it was swimming with its mother in the delightfully warm waters of the Amazon River among the piranhas, crocodiles, poisonous snakes, and other good friends, and was as happy as a hippo. And that one night it was captured, snatched out of the water, and shipped to a freezing-cold country, where it had wound up in a pet store. And that one day a fat little boy had come in with his father, who had yelled at the shop owner and shown her the bite marks on his fat little boy’s hand. Then the little boy had discovered the snake. His face had lit up and he had shoved his dad, pointed, and yelled: “Anna Conda!” And then that was its name. Even though Anna Conda was a girl’s name and he was a boy! Or that’s what he thought, anyway.

Anna Conda had wound up in a cage in Hovseter and had been fed some pasty white, round, slippery balls that tasted like fish while the little boy poked it in the side with sticks. This had all happened more than thirty years ago, but Anna Conda would still wake up from this awful nightmare and would have been drenched in sweat if constrictors could sweat. And then it exhaled in relief because it wasn’t in the apartment in Hovseter, but in the delightfully warm sewer pipes beneath downtown Oslo.

What had happened was that one night the little boy had forgotten to lock the cage, and Anna Conda had managed to escape through the open bedroom window, down along the downspout to the street, where after a great deal of searching and a couple of hysterical women’s screams, it had found a loose manhole cover. That first night in the Oslo Municipal Sewer and Drainage System, it had lain curled up in a corner scared to death. But that had quickly passed. And by the next day, it had started doing what anacondas do: squeezing the heck out of things and then eating them. Because there were lots of Rattus norvegicus, bats, and regular old mice down there. It wasn’t quite the Amazon, perhaps, but it wasn’t that bad either. Just the other day it had even come across a genuine Mongolian water vole.

Now that Anna Conda had gotten so big, it had started easing up on constricting the food first—it just swallowed it, which was so much easier. It was pretty sure it remembered its mother saying that it wasn’t good table manners to swallow food without properly squeezing the heck out of it first, but there wasn’t anyone down here to notice. So Anna Conda had just swallowed the tiny, glowing piece of meat with the red hair. And now it had the feeling that that might not have been such a good idea. Because the reason it had woken up was that it suspected something had exploded somewhere inside it and that a massive burp was on its way and wanted out. And Anna Conda suspected that the food was planning to go the same way. So Anna Conda clenched its jaws shut as it felt its long body inflate. And inflate. But it didn’t give up; it clenched its jaws harder. Its body was starting to resemble an enormous sausage-shaped balloon and it was still swelling. But Anna Conda didn’t give up; what’s eaten is eaten. It was so inflated now that its snaky black scales were smashed against the sides of the sewer pipe. Its jaws ached. Soon it wouldn’t be able to take anymore. And the pressure from within was only getting worse.

Soon it wouldn’t …

Wouldn’t!

Anna Conda’s mouth popped open and out came a burp. And we’re not just talking about a regular burp, but a thunderclap of a burp that caused all of southwestern Oslo to shake in its foundations. And just like when you stop pinching together the end of a sausage-shaped balloon, Anna Conda took off like a rocket through the Oslo sewer system. Vroom! It was like a cannonball being shot out of a cannon. The speed just increased and when it was shot out of the sewer pipe under the wharf a few nanoseconds later, it kept going quite a ways out over the fjord before it turned and headed straight up into the air. And exactly like a runaway balloon, it made sudden, unpredictable turns all over the place, accompanied by a flapping, farting sound. Until it was completely deflated and it landed like a moth-eaten lion pelt in a spruce tree somewhere out on the Nesodden Peninsula.

Nilly was lying on his back, floating in the sewer water like a piece of poop, as he stared up at the ceiling and laughed. His laughter echoed through the network of sewer pipes. He was free! He’d been shot out of the anaconda’s jaws like a projectile about one minute after he’d swallowed the fartonaut powder. Who would have thought it would feel so liberating to be in a sewer!

But after a while Nilly stopped laughing. Because actually, all of his problems were far from solved. The snake would soon find its way back into the sewer, and he really didn’t want to be there when that happened. And how was he going to not be there?

He had to get out. He looked around. There was not a single exit sign to be seen. Just a wooden crate bobbing up and down in the water in the semidarkness. He clambered up onto it and paddled inward. Or outward. He wasn’t sure which way. And after he’d paddled around various turns and corners for twenty minutes, he still didn’t know where he was or how he was going to find an exit. He stopped paddling. And as he sat there listening to the silence, he thought he heard a faint sound. No, he wasn’t imagining it, it was a sound. And it was getting louder. A terrible sound. The sound of an explosion, a plane crash, and an avalanche, a sound that sends shivers down your spine, and sends the devil packing. And Nilly knew that that sound could only be one thing: the Dølgen School Marching Band.

Nilly paddled as fast as he could toward the sound, went around two corners, and sure enough: He saw a beam of sunlight coming down from something that could only be a shaft leading up to the surface. Nilly paddled over to a metal ladder that was bolted to the side of the shaft and looked up. The ladder led up to where the light was coming from, somewhere way up above him. And, sure enough, up at the top he saw the bottom of a manhole cover. Nilly hopped off the wooden crate and climbed up as fast as he could. When he was halfway up he glanced down, causing his heart to skip a beat and making him immediately promise himself that he wouldn’t do that again. Sometimes it’s just better not to know how high up you are.

When Nilly had made it all the way to the top and could hear the sound of the Dølgen School Marching Band moving away, he put his shoulder against the manhole cover and pushed as hard as he could. Then he tried one more time. And again. But unfortunately what Doctor Proctor had said was true: The manhole covers in this city would not budge. And there wasn’t a single grain of fartonaut powder left for him to blast the iron cover off with.

Nilly shouted as loud as he could: “Help! Help!”

The sound of the most hideous marching band music in the Northern Hemisphere was almost gone now, and Nilly’s shouts were drowned out by the cars that had started driving on the street above him.

“Help! Help!” Nilly shouted. “There’s an anaconda living down here, and it’s on its way home for lunch!”

Nilly knew probably no one would believe that, but what did it matter since no one could hear him anyway?

Nilly held on until his arms ached, and he shouted until he was so hoarse that only a low rasping came from his throat. Resigned, he climbed back down and lay on the crate, exhausted. Then he sat up and started listening for the sound of a snake hissing. And while he was sitting like that, he happened to see a ray of light from the manhole cover shine on some deep holes punched through the lid of the crate he was sitting on. Holes left by large and rather sharp fangs. And some red letters that were printed on the lid:

CAUTION! HIGHLY EXPLOSIVE SPECIAL GUNPOWDER FROM SHANGHAI FOR THE BIG AND ALMOST WORLD-FAMOUS ROYAL SALUTE AT AKERSHUS FORTRESS

Yikes, Nilly thought.

Yeah, yeah, so what? Nilly thought.

Wait a minute, Nilly thought.

Maybe…, Nilly thought.

He felt around in his back pocket. And there it was. He took it out. It was the half-chewed matchstick he’d gotten from Truls as payment for the bag of fartonaut powder. Of course it was wet and practically chewed in half, but it still had the red tip made of sulfur.

He held the matchstick in the beam of sunlight, feeling how the sun warmed the skin on his hand. And two questions occurred to him now. Number one: How long would you have to hold a match in the sun on a morning in mid-May before it was dry enough to light? And number two: How long does it take an anaconda to swim across the fjord from somewhere over by the Nesodden Peninsula?

You’re going to get the answer right away. It takes almost exactly the same amount of time. Which is to say: It takes just about one hour and four minutes to dry a match. For an anaconda to swim across the fjord from the Nesodden Peninsula and make its way deep into the Oslo sewer system, it only takes one hour and three minutes. And after an hour and three minutes had passed, Nilly noticed his hand starting to shake from holding it up in the beam of sunlight for so long. And right then he heard a familiar hissing noise.

Oh no, Nilly thought, since he felt that getting eaten once in twenty-four hours was more than enough.

He struck the match hard against the metal on the inside of the sewer pipe, but nothing happened.

The hissing noise came closer.

Nilly struck the match against the metal again. The red tip sparked but didn’t light. And then Nilly was once again staring into the big pink mouth of the largest anaconda anyone had ever seen. The mouth came around the corner, and Nilly thought, This time that’s it, a red-haired boy only gets so many chances.

He pulled the match along the wall one last time.

It sparked. It sizzled. It ignited.

Nilly acted very quickly now. He set the match down in one of the holes left by the fangs in the crate with the burning end up. Then he dove into the water and swam away underwater as fast as he could. And for the first time he was glad that this was really nasty, filthy sewer water, where it would be impossible to see or smell much of anything besides nasty, filthy sewer water. And the match burned. From the top to the bottom. From the top of the crate down into the highly explosive special gunpowder from Shanghai.

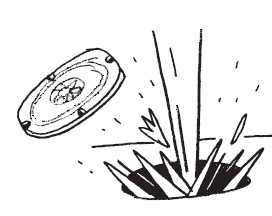

And for the second time that day, the foundations of downtown Oslo shook. On Sverdrup Street a manhole cover shot up into the air. Drivers slammed on their brakes and pedestrians froze on the sidewalk, staring at the hole in the street. The manhole cover was followed by a geyser of wooden splinters and sewage. And then nothing. And then a tiny, red-haired, and soaking wet boy climbed up out of the hole. He bowed politely to the frightened onlookers before rolling up his shirtsleeves.

Then he leaned over the manhole, spit some sewer water into it, and yelled, “Take that, you earthworm!”

Before turning around to face the pedestrians, the shopkeepers who had come out of their shops to see what was going on, and the drivers who had rolled down their windows.

“I’m Nilly!” the little boy yelled with his hands on his hips. “Anyone have anything to say about that?”

But the people on Sverdrup Street just stared, their mouths hanging open, at this strange being that had emerged from the inside of the earth.

“Nope, that’s what I thought,” said the boy, spitting one more time and walking away.