Chapter 3: Basic Music Notation

“Music expresses that which cannot be put into words and that

which cannot remain silent.”

― Victor Hugo

Music, like language, existed for thousands of years before anyone thought to invent a way to write it down so that it could be more easily replicated and passed on to others. Even in modern times, some professional musicians prefer learning and playing music by ear or as improvisation (making it up as they go along), without ever learning to read music or put it in writing. Even some popular and very successful modern singers were not or are not able to read or write music (e.g., Elvis Presley, Michael Jackson, and Taylor Swift). Those who find fault with modern music notation systems rightly point out that, after centuries of extension, elaboration, transformation, and tweaking, the current notation system is neither efficient nor intuitive. In fact, it can be downright confusing.

Nevertheless, without written music, we would not be able to experience the sheer complexity of the music of Mozart, be awed by the New York Philharmonic playing the William Tell Overture, or learn the tune to the Star Spangled Banner. It is a lot easier to study, share, replicate, perform, and discuss music when it has been written down. As this book delves deeper into music theory, it will often be necessary, for the sake of clarity, to represent musical concepts and procedures as they might be communicated to a musician via sheet music. Consequently, having a basic understanding of musical notation should help you get the most out

of this book.

Common Notation

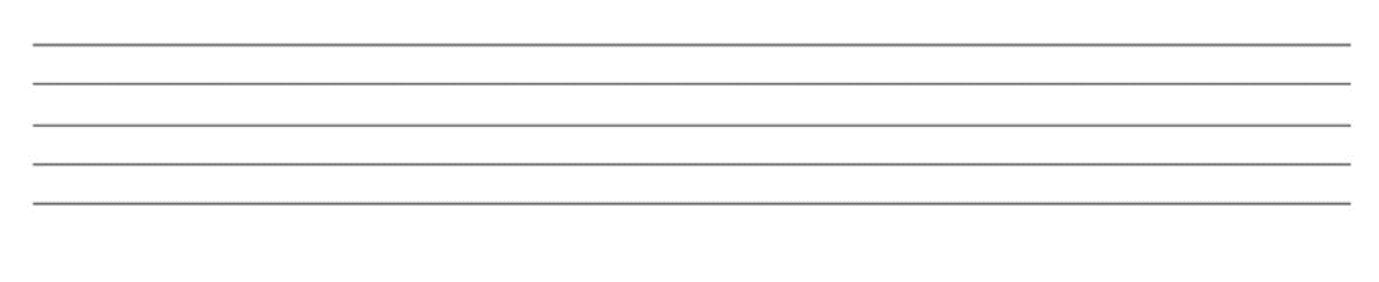

The generally accepted method of music notation, called common notation, begins with the staff, which is five horizontal lines that are evenly spaced vertically.

|

Figure 3.1: The Musical Staff

|

|

|

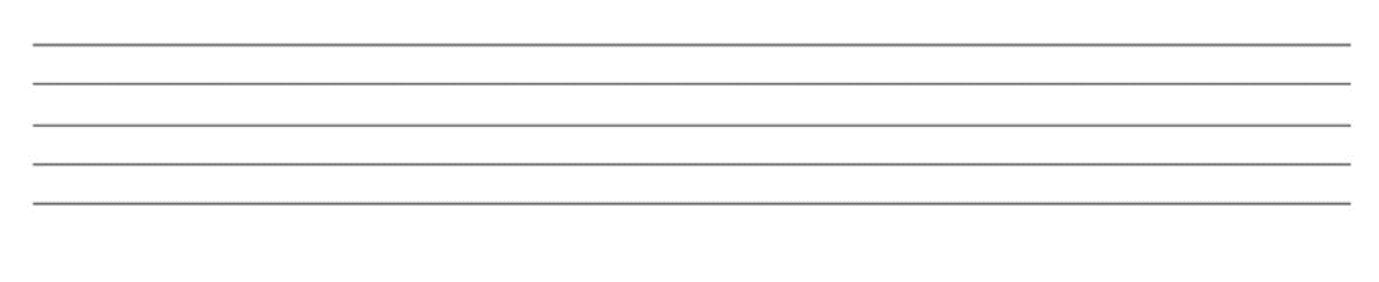

Vertical lines called “bar line” are also added to divide up the staff into short sections called “measures” (or bars). A double-bar vertical line, sometimes with both a heavy bar and a light bar, marks out larger sections of a musical work, with a heavy double-bar vertical line always used to indicate the very end of a piece of music.

|

Figure 3.2: The Musical Staff with Bar Lines

|

|

|

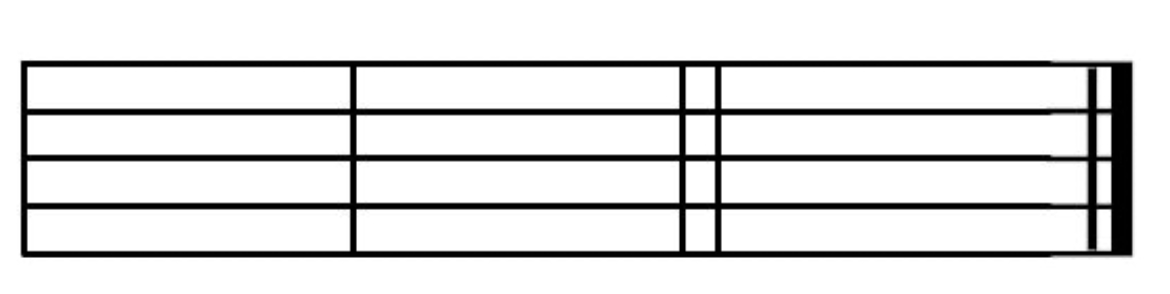

Each of the five lines and four spaces on the staff can also be assigned a specific letter. For example, under certain circumstances, starting with the bottom line, the letters assigned could be E, G, B, D, and F. Similarly, starting with the bottom space, the spaces could be designated as F, A, C, and E. Notice also that as you move from the bottom of the staff to the top, the letters assigned to the lines and spaces would be in alphabetical order, E, F, G, and then A, B, C, D, E, and F.

|

Figure 3.3: Letters For Lines and Spaces on Staff

|

|

|

On the staff as a whole, on the lines, in the spaces between the lines, or in the space above or below the staff, many different kinds of symbols can be written to tell the musician various things about how to play the music. These include the basic components of the music itself: note symbols (sounds) and rest symbols (silences). Other symbols on the staff include clef symbols, the key signature, the time signature, tempo markings, dynamic markings, repeats, and accent symbols. Three of the most important symbols on the staff, the clef symbol, the key signature, and the time signature, will always appear at the beginning of the staff.

|

Figure 3.4: A Musical Staff with Symbols

|

|

|

Musical Notes

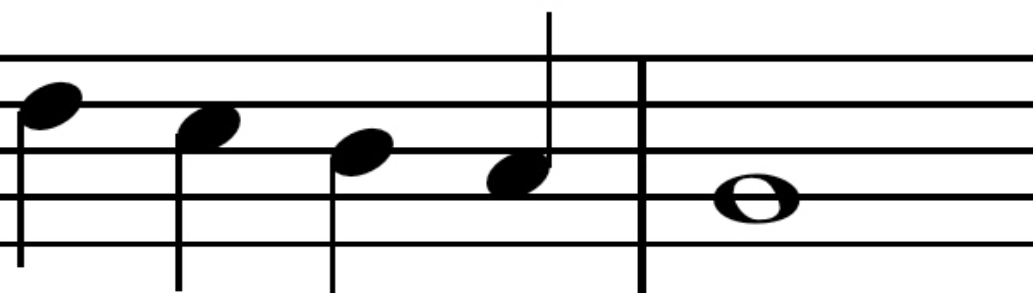

One of the most important symbols placed on a staff are, of course, the musical “notes,” and they can have up to three parts: the head, which is the round part of the note; a stem, which is a semi-vertical line extending up (or down) from the head; and sometimes a flag, which is a short wavy line extending out from the stem, like a flag on a flagpole. Furthermore, sometimes the head is solidly filled in, and in some cases, it has an open space in the middle.

More importantly, the notes tell a musician to make a particular sound at a specific pitch and for a particular duration. Usually, the pitch to be played by the musician is indicated by which line or in what space the note is written. For example, a note symbol written on the bottom line would indicate that the musician should play a sound with the pitch E, while a note symbol written in the third space from the bottom of the staff would instruct the musician to play a sound with the pitch of C. The length of time for which the sound is to be played is indicated by the type of note symbol used, e.g., whole notes, half notes, quarter notes, etc.

|

Figure 3.5: Notes on the Musical Staff

|

|

|

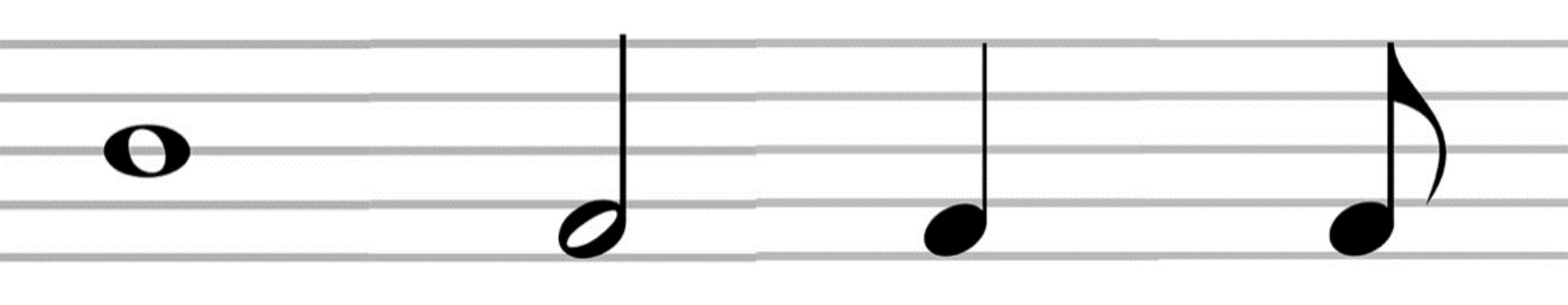

Without getting into the actual temporal length of a whole note, what is most important to know at this point is that as the name implies, a half note is played for half the time that a whole note is played, and a quarter note is played for one quarter the length of time of a whole note, and so on. Quarter notes, eighth notes, and sixteenth notes are the only notes with solid heads, and eighth and sixteenth notes are the only notes that have flags—one flag for an eighth note (quaver) and two flags for a sixteenth note (semi-quaver). Both whole notes and half notes have heads with an empty space in them, but of these two, only half notes have a stem.

|

Figure 3.6: Symbols for Musical Notes

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Whole Note Half Note

Quarter Note

Eighth Note

|

|

|

|

|

Notes with stems can also have their stems extend upward above the head or extend downward below the head. This variation has no implications for the music being played and is only done when the note is so close to the top of the staff that its stem would extend up beyond the top of the staff. Purely for clarity and stylistic purposes, the stem is pointed downward so that it remains entirely on the staff.

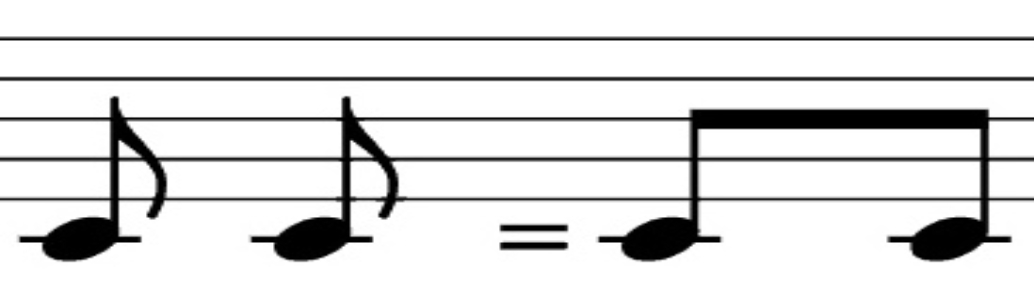

Notes that have flags on their stems (whether the stems are pointed up or down) can also be connected to each other using “beams” or “ligatures.” This is often done when two such notes that are the same duration occur one after the other. The flags on the two notes are removed and replaced with a beam that connects the tops of the stems of the two notes.

|

Figure 3.7: Notes with Beams Instead of Flags

|

|

|

If there are four of the same duration of notes in a sequence, they can also be separated into two groups, with each group of two connected by a double beam. Even a group of four such notes can be connected by a double beam. However, one important thing to keep in mind here is that the notes being connected in this way do not need to be the same pitch, only the same duration. In other words, an eighth note for a C and an eighth note for E that follows it, can still be connected using a beam. Using beams instead of flags also really has no implication for the music being played. It is also done simply to make the musical notation look less messy.

For any piece of music, multiple note symbols will be placed on the staff, and since music notation is always read from left to right, the order in which the notes appear on the the staff tells the musician the order in which they are to be played.

The notes that are identified by their positioning on the lines or spaces of the staff are called “natural notes”.

Sharps and Flats

When you compare the interval between two adjacent natural notes, you will see that the distance is not always the same. In fact, some pairs of notes are twice as far away from each other when

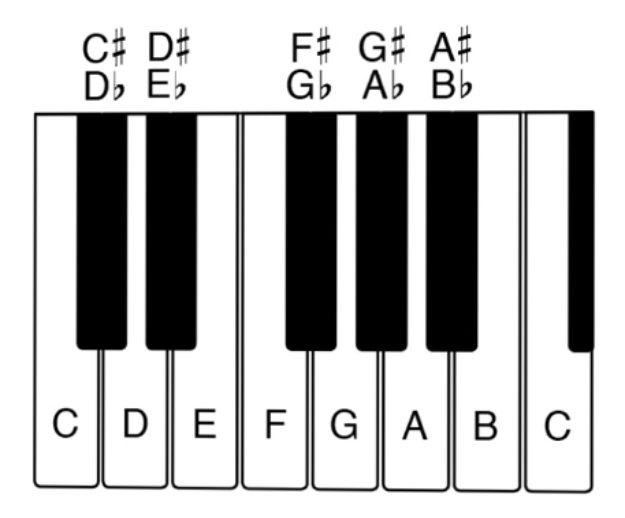

compared to other pairs of notes. The interval in frequency/pitch between those notes that are furthest apart is called a whole step or whole tone. In contrast, the interval between those notes that are closest together is called a half step or semitone. In Western music, additional notes are added between the natural notes that are a full step apart. These are called sharp notes and flat notes. In fact, on a piano keyboard, black keys were added between some of the white keys to make playing these notes possible on the piano. This has the effect then making all musical notes exactly one-half step apart.

It is also important to remember that calling the notes sharps and flats does not necessarily imply the corresponding pitches somehow have a “sharper” or “flatter” sounding timbre. Over centuries of music study, these names have just become the conventional way of referring to these notes.

|

Figure 3.8: Flat and Sharp Notes

|

|

|

A sharp note is one half step higher than the natural note next to it. On the staff, it can be designated by the symbol “superscript #” placed next to the letter for that note, e.g. F#

. The new note is called F sharp.

A flat note is one half step lower than the natural note next to it and it is designated by the symbol “superscript italic b” placed next to the letter for that note, e.g., Bb

. The new note is called B flat.

On a piano keyboard, the white keys play the natural notes, e.g., A, G, B, etc. The black keys play the sharp and flat notes, e.g., F sharp or B Flat. So, the distance between any key on a piano and a key next to it, whether white or black, is a half step or semitone.

In any octave, there are five sharp and flat notes: A#

/Bb

, C#

/Db

, D#

/Eb

, F#

/Gb

, and G#

/Ab

. Notice also that there are no sharps or flats between B and C or between E and F. That is because those notes

were already one-half step apart and so there was no need to add additional notes between them.

You may have also noticed that adjacent sharps and flats are exactly the same note, just with different names, e.g., G sharp and A flat. These are called enharmonic notes. And if you were to play these notes on a piano keyboard, you would use exactly the same black key to play both of them. So why give them different names? Whether you call the note a G sharp or an A flat isn’t just arbitrary. It can communicate important information about how the note functions as the music progresses. Remember, music progresses linearly over time, so a G sharp or A flat may sound completely different in the context of what notes are played before it, with it (as part of a chord), or after it.

For example, if your music includes a sequence of notes increasing in pitch (moving higher), and the sequence is to include a C sharp/D flat, it would make more sense to label the note as C sharp instead of D flat, so as to more accurately indicate that the notes are to continue ascending. Similarly, when the sequence of notes is descending in pitch, it would make more sense to label the note as D flat since that is more consistent with a continuation of the descent.

Octaves

Given that there are seven notes with letter names (A, B, C, D, E, F, and G), adding five sharp/flat combinations (A#

/Bb

, C#

/Db

, D#

/Eb

, F#

/Gb

, G#

/Ab

), results in twelve distinctive notes. These twelve notes collectively are called an octave or register, and the notes are the same for every octave, just at higher or lower pitches. And, as noted earlier, when two notes are exactly one octave apart, the frequency of the higher one is always that of the lower one.

Also, pitches of the twelve notes in an octave are always exactly one semitone (half step) apart. In fact, if we take the

frequency any note in an octave and multiply it by exactly 1.0595, the result will be the frequency of the next higher note in the octave. This number is called the “twelve root of 2” because if you multiply it by itself twelve times, the result is exactly two (and so the frequency/pitch highest note in an octave is exactly twice that of the lowest note).

This method of dividing the octave into twelve equal intervals is known as equal temperament tuning, and this will be discussed in more detail later later.

Around fifty years ago, the Acoustical Society of America introduced a register designation system based upon the layout of the standard piano keyboard. Specifically, the designation system begins with the first C note (and the octave based on it) leftmost on the piano keyboard, and extends up to (and including) the last B note seven octaves above it on the far right of the keyboard. Each octave in between is designated by a letter of the note that begins that octave, e.g. C, followed by a subscript number denoting the number of the octave within which that pitch resides, from lowest to highest (left to right on the keyboard). For example, the first C octave on the left would be C1

, the second C2

, and so on.

However, there are actually three keys on a standard piano keyboard to the left of the first C octave (C1

). These notes are labeled in two ways: A0

, Bb

0

, B0

, or simply A, Bb

, B. And C8

contains only one note, a very high C, and so it does not actually represent a full octave. The entire piano keyboard then spans the range from A0

to C8

.

Of course, musical instruments can play, and human ears can hear, musical notes from more than one octave. Pianos, for example, with eighty-eight keys on a full-size keyboard, can play as many as

seven octaves, as indicated above.

However, human ears, human voices, and musical instruments also have limits, and so there is a limited number of octaves available for music. Humans can hear a range of around ten octaves. However, seven of those octaves cover the bottom eighth of the range, from 20 Hz up to 2500 Hz, which corresponds roughly to the pitch range from E

♭

0

to E

♭

7

, which is slightly lower than the lowest pitch on a piano. Only the piano, harp and piccolo can go higher than E

♭

7

, and not by very much. The bottom note on a double bass or bass guitar, E1

, has a frequency of just over 40 Hz. Only the harp, piano, double bassoon, and organ can go below this. Even the best professional singers can usually perform only over a range of one and a half to just over two octaves.

The Chromatic Scale

The group of all possible musical notes is called the Chromatic Scale. Chromatic comes from the Greek word chrôma

, meaning color. The chromatic scale is then the group of “'notes with all possible colors”.

Every octave will always contain the same group of twelve possible notes (just at different pitches or in a different order). It doesn’t matter which octave is being discussed or on what note the octave begins. In this sense, then, all octaves are identical. Since the octave and a Chromatic scale both contain the group of possible notes, they are in effect then the same thing, and there is only one Chromatic scale. Nevertheless, understanding the concept of the Chromatic Scale will become important for topics I will discuss later in this book.

The Clef

At the leftmost end of every staff is a clef symbol. There are basically two different types of clef symbols in common music notation, the “treble clef” (sometimes also called a G clef) and the “bass clef” (sometimes called the F clef). Each serves as a kind of decoding key to tell you how to interpret what follows on the rest of the staff. More specifically, the clef tells you how to interpret the note symbols on the lines and in the spaces of the staff.

For example, a treble clef symbol tells you that the second line from the bottom (the line that the symbol curls around) is "G". Since the note letters follow alphabetically as you move up the staff, that means that, as we mentioned before, the notes on the lines of the staff for a treble clef are E, G, B, D, and F, while the spaces are F, A, C, and E.

|

Figure 3.9: The Treble Clef

|

|

|

A bass clef symbol tells you that the second line from the top (the one bracketed by the symbol's dots) is an F note. The notes are

still arranged in ascending alphabetical order, but they are all in different places than they were on the treble clef. So the lowermost line is a G note, followed by a B, D, F, and then an A, as you move up the staff, and the spaces are then A, C, E, and G.

|

Figure 3.10: The Bass Clef

|

|

|

The notes that appear on the Treble clef staff are those usually played by the right hand of a pianist, while those on the Bass clef are typically played by the left hand of the pianist. Similarly, notes on the bass clef are those usually played by deeper sounding musical instruments such as bassoons, tubas, cellos, bass guitars, and bass and baritone voices. In contrast, notes on a Treble clef staff are played by instruments such as flutes, piccolos, violins, soprano saxophones, and soprano voices.

The positioning of the notes on the two different staffs for treble and base clefs, which never changes, is such a fundamental concept in writing and reading music, that students are often taught mnemonics (memory aides) to help them learn and remember those relative positions. For example, as a way of remembering the notes on the lines of a treble clef staff, you can learn and remember the phrase “Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge”. The first letters of each of

these words E, G, B, D and F are then the letters corresponding to the lines on the staff. Similarly, if you just learn and remember the word FACE, that should help you remember the notes in the spaces of the treble clef staff, because the letters for the notes spell out that word as you move up the staff.

For the bass clef staff, a helpful mnemonic for remembering the notes on the lines might be “Good

Boys Do Fine Always”, and for the notes in the spaces it could be “All Cows Eat Grass”.

Music may also be written on multiple staves (plural of staff), especially when the different staves are to be played by the same musician simultaneously (left and right hand for a pianist) or by different musicians (members of a band or orchestra). More specifically, there will be a Treble clef staff at the top, and a Bass clef staff beneath it, joined together along the left side by a long vertical bar.

This is called a grand staff. And if we were to create a short additional line between the two staves (a ledger line), thus creating a single staff with 11 lines, the musical note commonly referred to as “Middle-C” is one line below the E on the bottom line of the Treble clef staff. Similarly, the A on the top line of the Bass clef staff is the A note one line below middle-C. And the spaces just below and above middle-C would be B and D notes, respectively.

|

Figure 3.11: The Grand Staff

|

|

|

Together, the Treble and Bass clefs cover most of the notes that are in the range of musical instruments and human voices.