Chapter 7: Music and Time

“The most exciting rhythms seem unexpected and complex, the most

beautiful melodies simple and inevitable.”

― W.H. Auden.

Unlike static works of art such as a paintings, photographs, or sculptures, which exist as “all of what they are” at every moment in time from the point at which they are created, music is an art form in which the passage of time is an important element of the work. In other words, music does not just stand still. Instead, it moves forward, progresses, changes, evolves, develops, repeats, grows, declines, and eventually ends. Thus, music not just acoustic, it is also temporal.

But of course, music is not a continuous stream of noise. Rather, music is an art form made up of a series of distinct events that happen over a period of time, usually in creatively planned patterns, one after the other, like words in a sentence, sentences in a poem or story, or scenes in a movie. Moreover, with regard to music, the precise timing of the events is also especially important. Musical events must happen at precisely the right times, for precisely the right duration, and in precisely the right way, for the music to work.

Finally, just as is the case with language, comprehending what is being communicated in music is not just based on understanding a particular note or phrase, but rather how the notes and phrases fit together over time and gradually create the meaning.

It is the temporal qualities of music that will be the focus of this chapter. Future chapters will focus on topics such as chords and chord progressions, melodies, dynamics, and composition, all of

which necessarily involve events happening over time, and so having some basic understanding of the temporal aspects of music will be essential for developing an understanding of those topics.

Temporal Qualities of Music

We can discuss the temporal qualities of music in terms of four fundamental elements, Beat, Tempo, Meter, and Rhythm.

-

Beat

—the background pulse of a piece of music.

-

Tempo

—the relatively fast or slow speed at which the music moves forward.

-

Meter

—how beats are organized, along with accents, silence, and notes, into discrete segments in a piece of music.

-

Rhythm

—the overall musical patterns established by the beat, tempo, and meter, and notes, along with the qualities of uniqueness, repetitiveness, expectancy, movement, and development.

Beat

. On a fundamental level, music moves forward through time as a series of discrete pulses. By discrete, I mean that each pulse gives way to complete silence before the next pulse occurs. With regard to music, we often call our subjective experience of one of these pulses “a beat” (even though, technically, a single pulse may extend over more than a single beat). For example, if you tap your finger on a table four times, one right after the other, you have performed four beats. Notice that each tap was a distinct event, and

not a continuous one.

Most importantly, it is a single “beat” that serves as the most basic organizing element for all music. Each tap on a drum, each note played (or vocalized) by a musician, or each silence, may count as one beat, with each piece of music made up of thousands of such beats occurring in succession.

Accents

. In any series of beats, one or more of them may receive more emphasis or accent than others. In fact, the strongest or accented beat is usually the one that occurs just after the bar line. So, if while tapping your finger four times, you say “ONE-two-three-four, ONE-two-three-four, you are putting accent on the ONE beat. The ONE beat is then the strong beat, and the next three beats are weaker beats. Of course, the pattern could also have been one-TWO-three-FOUR, one-TWO-three-FOUR, or ONE-two-three, ONE-two-three.

In all of these cases, the accent was “vocal,” but in composing music there are many possible ways of creating the desired emphasis on a beat, e.g., tapping a drum harder on the accented beat, using a different drum on the accented beat, playing or singing a note louder, playing or singing a note longer, playing a note with more intensity, playing or singing a note at a higher pitch, changing timbre on the accented note, etc. Any of these methods, when used correctly, can create emphasis that can be heard by listeners.

In any event, it is the number and relative positions of accented and unaccented beats that forms the “beat pattern” of a piece of music and underlies discussion of both meter and rhythm (more on this later).

Finally, as discussed earlier, music is not written on a staff in one long continuous stream. In order to keep music organized, and provide common reference points, written music is divided up into

smaller chunks called measures or bars. Most important for the topics covered in this chapter is that each measure can contain only a limited and specific number of beats.

The Upbeat and Downbeat

. The music concepts of beat and beat-pattern have evolved from centuries of study of human dance as well as from discussions of rhythmic patterns in poetry. When you place your foot down to begin a dance step, that is a strong first beat. As mentioned earlier, it is the first beat of a measure that usually receives the strongest accent and in fact this beat is called the Downbeat (crusis). In contrast, the Upbeat (anacrusis) is the last beat in the previous measure which immediately precedes the Downbeat.

Conductors communicate beat patterns with their baton in order to lead an orchestra or choir. The first beat of the measure is gestured with a downward motion, and in fact it is the reason why the first beat is called the Downbeat. Metaphorically, this is like putting the foot down on the first beat of a dance. Obviously, then the hand is raised to indicate an Upbeat.

This One Beat Up-One Beat Down relationship is a critical factor, both in terms of the composition of music and the subjective experience of music by listeners. It is the basis for the sense of forward movement in music. The Upbeat is an anticipation, a beginning, a request, a question, an opening. The Upbeat leads to the Downbeat and serves as a preparation for the Downbeat. On the other hand, the Downbeat is an ending, a fulfillment, a question answered, a promise kept, a completion; and this propels the music forward, so what happens on that beat needs to be clear, strong, powerful, attention getting, and should stand-out.

Notes

. As discussed in Chapter 3, musical notes do not only

tell you what pitch to play. By virtue of how they look, they also include information about how long (the duration) they should be played by an instrument or sung by a voice. So obviously, it is important for musicians to not only play (or sing) the right pitch, but also do so for the correct amount of time.

In any measure, a musician may play or sing four quarter notes in succession, one per beat, or play or sing two half notes, each lasting two beats, or they may play a whole note lasting for all four of the beats in a measure.

When there are four beats per measure, this is called Common Time, but other patterns are also possible (more on that later). The important point here is that, in Common Time, no matter what is done on each beat, the total number of beats per measure must always equal four.

Of course, as we already know, there are also musical notes that have shorter durational values than quarter notes: eighth notes, sixteenth notes, and even thirty-second notes and sixty-fourth notes. In Common Time, these notes would represent half-beats, quarter-beats, sixteenth beats, and thirty-second beats, respectively.

Musicians may also sometimes use dotted or augmented notes. The standard notation for this is to put a small dot next to the right side of the note. For example, a half note with a dot next to it says to play and hold the note for half again as many beats as the value of the note, e.g. three beats in the case of an augmented half note.

Triplets are another very common practice in music: three equal notes are being played in the space of two notes. The most common example is the 8th note triplet. An eighth note triplet is 3 eighth notes played in the space of 2 eighth notes (or one quarter-note); a quarter-note triplet spans the length of a half-note, and so on. So we also need a symbol that will allow us to communicate a

length of one third (33.3%) of the specific note, e.g. the eighth note. This is done by grouping the three eighth notes with a beam (replacing the flags on each note), and then adding a ‘3’ (or triplet) sign just above the beam. In fact, such beams are used only to group notes together that share a beat, never across beats.

|

Figure 7.1. Triplets on Musical Staff

|

|

|

Syncopation, which is common in dance music and a lot of popular music, occurs when a strong note is sounded either on a weak beat or off the beat, or when the sounding of a note is extended or suspended across multiple beats, or even across measure bars.

Rests

. In music, the spaces between musical notes and phrases are often as important as the notes themselves. At the very least, these pauses allow the listener to absorb each musical note or phrase before the next one starts. In fact, music can be perceived by listeners as more satisfying if it has a good balance between musical activity and silence.

In music terminology, these silences are called rests. Rests also count as beats, so, for example, a musical measure might contain three notes and a rest (four beats total).

Similar to notes, there are whole rests, half rests, quarter rests, and so on. And there are symbols for each that are placed on the

musical staff as instructions to the musician to be quiet for some period of time, or, in piano music, that the left or right hand should to stop playing for some period of time. Since there is to be no sound, the only information communicated by the rest symbol is the duration of the silence.

|

Figure 7.2. Rests on Musical Staff

|

|

|

|

Quarter Rests Half Rests Whole Rest

|

Normally rest symbols are placed in the same way as note symbols, evenly spaced across the bar from left to right.

Quarter rests and half rests can of course be mixed together with note symbols in any measure. However, the whole rest always fills an entire measure and so when it is used there can be no other notes or rests in that measure. In fact, while the whole-rest technically has a theoretical length of four quarter-notes, it is not uncommon for it to be used for a full measure regardless of how many beats are in that measure. In fact, it may be better to think of the whole rest symbol as indicating “rest for the whole measure”.

Since it occupies the whole measure, the whole-rest symbol is always placed in the centre. The half-rest symbol looks similar to the whole-rest symbol, but it is placed above the third staff line, rather

than hanging from the fourth line.

The eighth-rest, sixteenth-rest, thirty-second-rest and sixty-fourth-rest symbols use the same basic figure, but each has an extra hook. Notice that this parallels the way equivalent note symbols are constructed, with each having an extra flag. Two or more rest symbols together simply extends the size of the rest to their total length. Rests are also sometimes dotted or augmented, with the same implications as for augmented notes. And in common time, no matter how many different kinds of notes or rests are in a measure, the total number of beats in that measure must still always total to four.

Finally, it is important to point out that rests do not imply that the musician should let their mind wander while they are happening, even though for instrumentalists or singers in a group, the rests can often be quite long. Continuing to follow along with “the beat” of the music is essential if the musician is going to resume playing or singing at precisely the right beat or moment. Timing is everything in music. It is a good idea to become so familiar with the beat pattern of the music that you don’t even realize you’re counting beats anymore.

Tempo

. The word tempo comes from tempus, the Latin word for time, and tempo is another crucial element in music. It describes the speed at which the beats happen — faster or slower.

The ticking of a clock and a human heartbeat are good examples of tempos. In the case of the clock, each individual “tick” is the equivalent of one beat and roughly corresponds to one second of time. So, for most clocks the tempo would be sixty ticks or beats per minute because there are sixty seconds per minute. Similarly, the normal resting heart rate or tempo for adult humans is between 60 to 100 beats per minute.

In fact, in music, tempo is also usually expressed in beats per minute, or BPM (for example 80 bpm means 80 beats per minute).

However, tempo is not only about the speed of the music. The tempo also is an important factor in setting the basic mood of a piece of music. Music that is played very, very slowly can impart a feeling of extreme somberness, whereas music played very, very quickly can seem happy and bright.

Of course, if a composer intends that a piece of music will be played quickly and cheerfully, or slowly and somberly, they need a way to communicate that intent to musicians. Prior to the 17th century, though, composers had no real control over how their transcribed music would be performed by others, especially by those who had never heard the pieces performed by their creator. It was only in the 1600s that the concept of using dynamic markings in sheet music began to be employed. Dynamic markings are like musical punctuation — they’re the markings in a musical sentence that tell musicians how to most effectively convey the intent of the composer.

Tempo markings, which are only one of several types of dynamic markings, indicate how fast or slow music should be played. Traditionally, Italian words are used, simply because when these phrases came into use (1600–1750), the bulk of European music came from Italian composers. The markings are usually written above the staff near the clef symbol at the beginning of a piece of music.

|

Figure 7.3: The Most Common Tempo Markings

|

|

Larghissimo

|

Very, Very Slow

|

|

Grave

|

Very Slow

|

|

Lento

|

Slowly

|

|

Andante

|

At Walking Pace

|

|

Marcia Moderato

|

Moderately as in Marching

|

|

Moderato

|

Moderate Speed

|

|

Allegretto

|

Moderately Fast

|

|

Allegro

|

Fast

|

|

Allegrissimo

|

Very Fast

|

|

Presto

|

Very, Very Fast

|

|

|

These terms can be somewhat ambiguous, overlapping, and subject to interpretation, and so have had slightly different meanings at different points in history. For more precise indications of tempo, composers can also place a metronome mark in the music. The metronome is a mechanical or electronic device which can be set to click or flash a specified number of times per minute. For example, the metronome mark,

= 80, would indicate that the piece should be played at the tempo of 80 beats per minute.

|

Figure 7.4. Metronome Mark on Musical Staff

|

|

|

It should also be noted that tempo can change during a piece of music. Classical music routinely uses tempo changes to add expression and drama. For example, it is not uncommon to use a gradual slowdown in the last few bars of a song (called rallentando) to produce a more satisfying ending. Less common is the opposite effect - accelerando - where the tempo gradually increases. You will sometimes hear accelerando in dance or folk songs - such as Zorba The Greek - as they pick up speed. The following tempo markings indicate that the tempo should change:

|

Figure 7.5: Common Tempo Change Markings

|

|

Accelerando

|

Getting Faster

|

|

Ritardondo

|

Getting Slower

|

|

Rallentando

|

Gradually Slowing Down

|

|

A Tempo

|

Return to Original Pace

|

|

|

Meter

. In any given piece of music, the pattern of strong and weak beats, the presence of inaudible but implied rest beats, the grouping of beats, and rests into measures, and the tempo, combine to give each piece of music complex and distinctive temporal characteristics. So does the varying durations of notes, and their articulation (more on this later). We call these temporal characteristics the meter of a piece of music.

Western music inherited the concept of meter from lyric poetry where it can denotes the number of lines in a verse; the number of syllables in each line; and the arrangement of those syllables as long or short, accented or unaccented. Haiku poetry is a very good example of this, as are limericks,

If you tap your finger on a table, then wait approximately one second, then tap again, and then again wait one second, you have not only performed four beats, but also beats with a specific pattern. Of course, other beat patterns are possible: for example, tap, pause, pause, pause, or tap, tap, pause, pause. Although different, each of these examples also contains four beats (some accented and some not accented). These patterns and how quickly they progress, are then key elements in the meter. You may also be familiar with the 'one - two - three - one - two - three' feel of a waltz, or the 'left - right - left - right' feel of a march. These are both also examples of meter.

Rhythm

. There is much disagreement amongst music theorists

as to what constitutes rhythm, and there are many reasons for this. In part, it is because rhythm has often been confused with one or more of its constituent, but not wholly separate, elements, such as beat, accent, meter, and tempo. This confusion can be exacerbated by the use of the term, often by the same writer in the same work, to refer to very different aspects of music, e.g., a pattern of beats and the pattern of notes of differing durations. Another compounding factor is that various types of instruments: drums, wood blocks, bass, bass guitar, piano, and even synthesizers may all be considered rhythm instruments, depending on the context. It may also be then that rhythm occurs on many different levels in music and so for any clear definition, those layers need to be teased apart. Finally, there is also clearly a subjective component to rhythm, and this often gets confused with the objective characteristics of the music.

On a very basic and objective level, rhythm certainly refers to the repetition in patterns of beats, silence (rests), and emphasis (accents) in music. It may even be argued that music requires rhythm. In fact, for some types of music, the rhythm is and is intended to be the most important component of the music. This is certainly true of drum solos. Rhythmic chants also fit this description. Also, music composed primarily for dancing, e.g., some music by Michael Jackson, and modern electro pop and trance music (Infernal’s From Paris To Berlin), is primarily rhythmic, with the actual notes being played or lyrics of less importance. Similarly, in hip hop music, the rhythmic delivery of the lyrics is the most important element of the style.

However, rhythm can also obviously function as the propulsive engine of a piece of music because it gives a foundation to a composition and provides guidance for musicians playing that music. Most musical ensembles, like symphony orchestras, big bands, marching bands, and folk, pop, and rock groups, contain a

“rhythm section” that is responsible for providing the rhythmic backbone for the music of the entire group.

Another element of music that often gets discussed in relation to rhythm is the creative and progressing pattern of notes of varying durations, played by one or more instruments, along with rests of varying durations, in a piece of music. As I will discuss later, this is essentially what constitutes the melody of a piece of music. And while there clearly can be rhythm without melody, when there is a clearly defined melody, aspects of that melody can also be experienced by listeners as contributing to the overall rhythm of the music, above and beyond what is contributed by a rhythm section.

Finally, rhythm is also, at least in part, subjective. It involves our initial perceptions of variations as well as pattern recognition (which some people are better at than others); specifically, the recognition and anticipation of a pattern of beats, some accented and some not, that we mentally abstract from the music as it unfolds in time. And we don’t always see the patterns immediately. But when we do recognize the patterns, we then develop expectations regarding what will happen next. In fact, once we recognize the pattern, we often react behaviorally to our perceptions of the rhythm: we tap our feet, we dance, we march, because we “feel” the rhythm internally.

Moreover, in everyday colloquial talk, when we say of someone that they are "keeping time" or "in time" with the music, what we are saying is that they are demonstrating the ability to perceive, comprehend, and consistently replicate in their own behavior, e.g. hand clapping, foot tapping, drumming, etc., the unique rhythmic pattern of the music they are hearing.

When we say that someone has “rhythm” what we are in effect saying is that the person has perhaps a better than average ability or even a special ability to hear, sense, recognize, understand, feel, and

replicate precisely the rhythmic qualities of music. This ability is indeed one quality that distinguishes great musicians from not so great ones. Drummers certainly rely on their abilities to comprehend and reproduce in a consistent way the rhythm underlying a piece of music. Pianists rely on their sense of rhythm to keep the pace of their playing consistent throughout a performance, and marching bands coordinate their music with their movement, as well as with each other, because of their sensitivity to the rhythm.

It may also be rhythm should not be understood as simply a series of discrete independent units, e.g., beats, notes, accents, etc., strung together in a mechanical, additive, way like beads. Instead, it might be better to think of rhythm as an organic process of understanding in which smaller temporal elements add up synergistically over time, evolving into a experience that is greater than the sum of its parts—an experience that we eventually come to recognize and define as the rhythm of the music.

Time Signatures

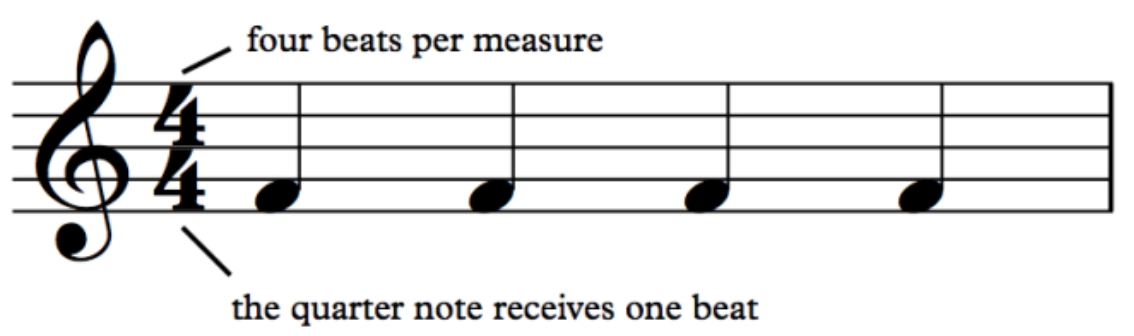

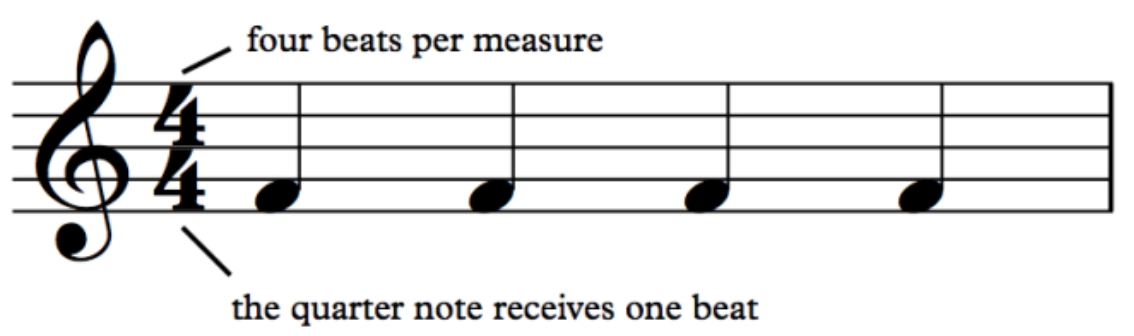

In written musical notation, there is a common method for communicating to musicians the particular meter of a piece of music. It is done with a Time Signature.

Figure 7.6. Time Signature on Musical Staff

Figure 7.6. Time Signature on Musical Staff

|

|

Along with Key Signatures, Time signatures are one of the most important forms of musical notation. Time signatures consist of two numbers, resembling a fraction (but they should not be confused with fractions). The time signature is always placed on the musical staff to the right of the clef symbol, just below tempo notations, and just after the key signature. And strictly speaking, the numbers should be placed one on top of the other, as they appear on staff lines.

The time signature says two things: how many beats are in a measure, and which value of written note is to be counted as a single beat.

If the top number is three, then each measure contains three beats. If the top number is four, then each measure contains four beats.

If the bottom number is four, then the largest note that can occupy one beat is a quarter note (two eighth notes, four sixteenth notes, etc., could also occupy one beat). Moreover, four is not the only number which can appear on the bottom of a time signature. For example, instead of quarter-notes, time signatures can also use an eighth-note as the maximum size of one beat. This is quite common. Other maximum beat sizes, such as whole-notes, half notes, sixteenth-notes, thirty-second-notes, and so on, are also theoretically possible, but are not particularly useful and are generally quite rare.

Another important point here is that the time signature in effect also determines the actual length of the measure. For example, when the bottom number is four, and the top number is four, the measure must be the equivalent of four quarter notes long. But any combination of notes or rests could be used to fill this space, e.g., one whole note, one whole rest, two half notes, one half note and a half rest, three quarter notes and a quarter rest, two quarter notes

and a half rest, three quarter notes and two eighth notes, two quarter notes, one eighth note, and two sixteenth notes, etc. As long as the total value of the symbols included in the measure total up to no more than the length of four quarter notes, consistency with the time signature has been maintained.

But what if the bottom number is two and the top number three? This means that there are three beats in the measure, and each beat will be a half-note. Thus, the measure is three half notes long, and this also could be manifested in numerous ways, e.g., a whole note followed by a half note, a whole rest, or a single dotted whole note.

Common Time

As mentioned earlier, common time uses the 4/4 time signature, which indicates a four beat measure, where each beat is a quarter-note long. This is by far the most used time signature used by composers and you will often see it notated simply as a 'C' for common time.

The two basic beat patterns or meters in music are duple and triple. An example of duple meter is a march, where the LEFT – right – LEFT – right, is best represented by STRONG – weak, STRONG – weak. An example of triple meter is a typical waltz, ONE – two – three, ONE – two – three.

Types of Time Signatures

Time signatures can be sorted into different types along two dimensions as the table below indicates.

The first dimension is simple or compound time. The second

dimension is duple, triple, or quadruple time.

|

Figure 7.7. Time Signatures

|

|

Simple Time

|

Compound Time

|

|

Duple Time

|

2/2, 2/4, 2/8

|

6/8, 6/4

|

|

Triple Time

|

3/4, 3/2, 3/8

|

9/8, 9/2, 9/4

|

|

Quadruple Time

|

4/4, 4/2, 4/8

|

12/8, 12/16

|

|

|

|

Simple Time

Simple Duple

. For example, 2/4 time is Simple Duple time. Duple refers to the two beats per measure (the top number), whereas Simple, based on the bottom number, means that each beat can be divided up into two notes. Other examples of simple duple time would include: 2/8, and 2/2, also known as “cut time” (or alla breve). The 2/2 time signature is also alternatively represented by a C symbol except that the C has a slash through it—the C of Common Time is being slashed or “cut.”

Simple Triple

. An example would be 3/4 time. Triple refers to three beats per measure (top number), even though the bottom

number still indicates that each beat can be divided into two notes. So a 3/4 time signature indicates a Triple (three-beat) meter, where each beat is a quarter-note long. The total length of each bar will therefore be three quarter-notes, or 3/4 of a whole-note. Similarly, 3/2 and 3/8 are simple triples.

Simple Quadruple

. This would include 4/4 (common) time as well as 4/2 time and 4/8 time. There are four beats per measure, but depending on the bottom number, those four beats may be composed of one quarter note each, two eighth notes each, or covering two half notes.

A simple meter time signature will always have 2, 3, or 4 as the top number, and any time you are tempted to count “one two one two” you are dealing with simple time.

Compound Time

Compound time is the name given to music when the beats can be divided into thirds. Whenever you count to a piece “one two three one two three”, as for a waltz, you are counting to compound time.

Compound Duple

. An example of a compound duple would be 6/8 time. Notice that the six eighth notes can be grouped in either of two ways using beams: as two beats made up of three eighth notes each, or as three beats of two eighth notes each. However, since the latter pattern is exactly the same as the 3/4 Simple Triple time, the 6/8 meter is always classified as a compound duple.

In any compound meter, the beat unit is always a dotted note. Also, any time signature with a 6 on top will be a Compound Duple, e.g., 6/8 or 6/4.

Compound Triple

. An example of a Compound Triple would be 9/8. There are nine beats composed of three dotted quarter notes each, making this a triple. And since each beat is made up of three notes, the meter is compound. Any time signature with a nine on top is a Compound Triple, including 9/2, 9/4, and 9/16.

Compound Quadruple

. The time signature 12/8 is an example of a Compound Quadruple. There are four beats making it a quadruple, and three nots per beat making it a compound meter. Any meter with 12 on top is a Compound Quadruple, e.g., 12/8 and 12/16.

Composite Time

Time signatures with larger beat numbers are also possible, and these are known as composite meters. In such cases, the larger beat count is usually broken down into a combination of duples, triples or quadruples. In fact, any time the top number (beats per measure) is not divisible by 2 or 3, such as in time signatures like 5/4, 7/4 or 7/8, this is composite time.

= 80, would indicate that the piece should be played at the tempo of 80 beats per minute.

= 80, would indicate that the piece should be played at the tempo of 80 beats per minute.

Figure 7.6. Time Signature on Musical Staff

Figure 7.6. Time Signature on Musical Staff