TWO

HOW WE GOT HERE

The Great Displacement didn’t arrive overnight. It has been building for decades as the economy and labor market changed in response to improving technology, financialization, changing corporate norms, and globalization.

In the 1970s, when my parents worked at GE and Blue Cross Blue Shield in upstate New York, their companies provided generous pensions and expected them to stay for decades. Community banks were boring businesses that lent money to local companies for a modest return. Over 20 percent of workers were unionized. Some economic problems existed—growth was uneven and inflation periodically high. But income inequality was low, jobs provided benefits, and Main Street businesses were the drivers of the economy. There were only three television networks, and in my house we watched them on a TV with an antenna that we fiddled with to make the picture clearer.

That all seems awfully quaint today. Pensions disappeared for private-sector employees years ago. Most community banks were gobbled up by one of the mega-banks in the 1990s—today five banks control 50 percent of the commercial banking industry, which itself mushroomed to the point where finance enjoys about 25 percent of all corporate profits. Union membership fell by 50 percent. Ninety-four percent of the jobs created between 2005 and 2015 were temp or contractor jobs without benefits; people working multiple gigs to make ends meet is increasingly the norm. Real wages have been flat or even declining. The chances that an American born in 1990 will earn more than their parents are down to 50 percent; for Americans born in 1940 the same figure was 92 percent.

Thanks to Milton Friedman, Jack Welch, and other corporate titans, the goals of large companies began to change in the 1970s and early 1980s. The notion they espoused—that a company exists only to maximize its share price—became gospel in business schools and boardrooms around the country. Companies were pushed to adopt shareholder value as their sole measuring stick. Hostile takeovers, shareholder lawsuits, and later activist hedge funds served as prompts to ensure that managers were committed to profitability at all costs. On the flip side, CEOs were granted stock options for the first time that wedded their individual gain to the company’s share price. The ratio of CEO to worker pay rose from 20 to 1 in 1965 to 271 to 1 in 2016. Benefits were streamlined and reduced and the relationship between company and employee weakened to become more transactional.

Simultaneously, the major banks grew and evolved as Depression-era regulations separating consumer lending and investment banking were abolished. Financial deregulation started under Ronald Reagan in 1980 and culminated in the Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999 under Bill Clinton that really set the banks loose. The securities industry grew 500 percent as a share of GDP between 1980 and the 2000s while ordinary bank deposits shrank from 70 percent to 50 percent. Financial products multiplied as even Main Street companies were driven to pursue financial engineering to manage their affairs. GE, my dad’s old company and once a beacon of manufacturing, became the fifth biggest financial institution in the country by 2007.

With improved technology and new access to global markets, American companies realized they could outsource manufacturing, information technology, and customer service to Chinese and Mexican factories and Indian programmers and call centers. U.S. companies outsourced and offshored 14 million jobs by 2013, many of which would have previously been filled by domestic workers at higher wages. This resulted in lower prices, higher efficiencies, and some new opportunities but also increased pressures on American workers who now had to compete with a global labor pool.

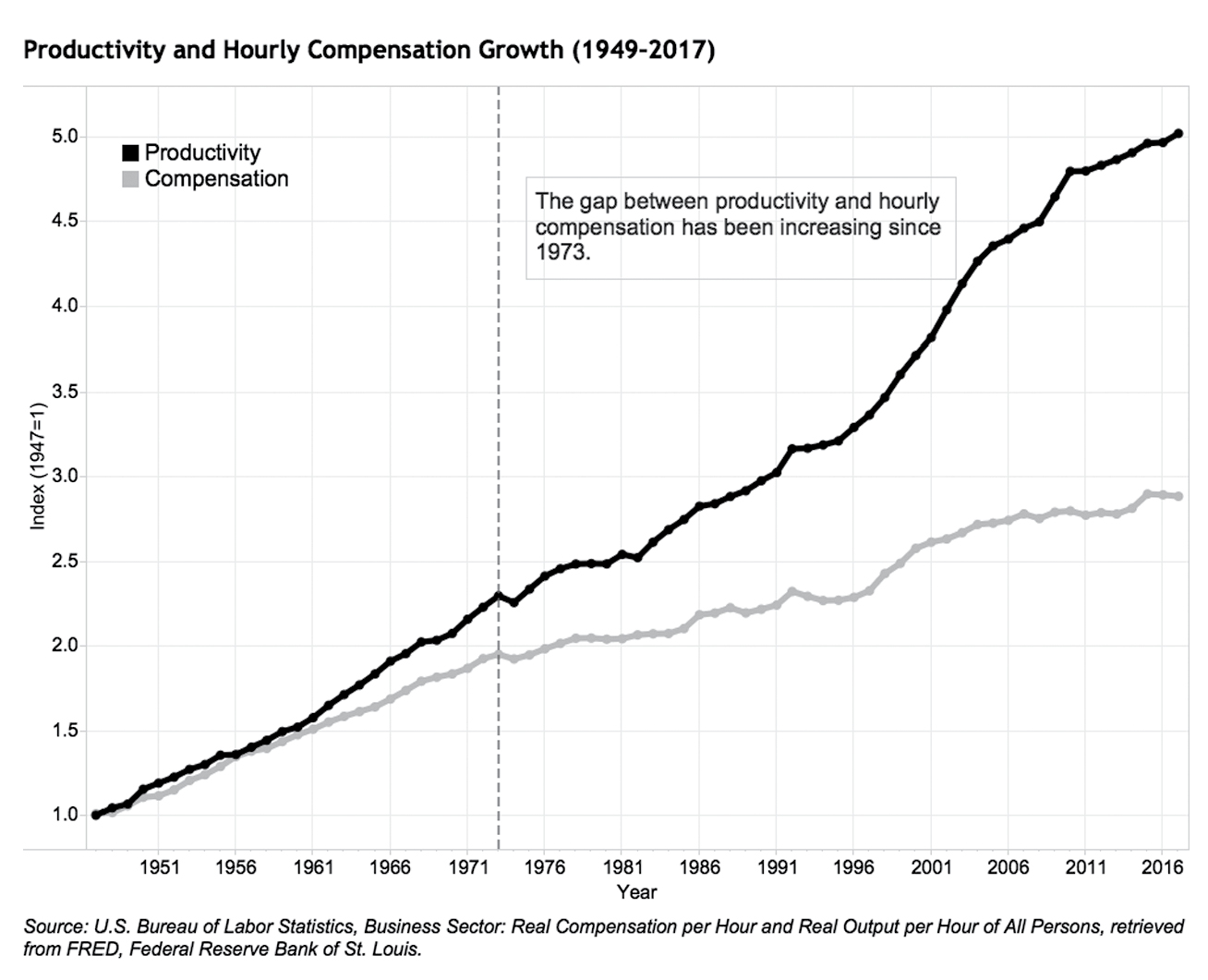

Automation started out on farms earlier in the century with tractors and then migrated to factories in the 1970s. Manufacturing employment began to slip around 1978 as wage growth began to fall. Median wages used to go up in lockstep with productivity and GDP growth before diverging sharply in the 1970s. Since 1973, productivity has skyrocketed relative to the hourly compensation of the average wage earner:

How workers are compensated and how their companies perform stopped being aligned over the same period. Even as corporate profitability has soared to record highs, workers are earning less. The share of GDP going to wages has fallen from almost 54 percent in 1970 to 44 percent in 2013, while the share going to corporate profits went from about 4 percent to 11 percent. Being a shareholder has been great for your bottom line. Being a worker, not so much.

Today, inequality has surged to historic levels, with benefits flowing increasingly to the top 1 percent and 20 percent of earners due to an aggregation of capital at the top and increased winner-take-all economics. The top 1 percent have accrued 52 percent of the real income growth in America since 2009. Technology is a big part of this story, as it tends to lead to a small handful of winners. Studies have shown that everyone is less happy in an unequal society—even those at the top. The wealthy experience higher levels of depression and suspicion in unequal societies; apparently, being high status is easier when you don’t feel bad about it.

JOBS DON’T GROW LIKE THEY USED TO

Companies can now prosper, grow, and mint record profits without hiring many people or increasing wages. Both job creation and wage growth have been weaker than the top-line economic growth would suggest since the 1970s. In each of the last several decades, the economy has created lower percentages of new jobs, including no new net jobs between 2000 and 2010 due to the Great Recession.

The changing role of labor can be seen in the time it has taken to recover from the past several recessions. The United States has suffered several major recessions since 1980. Each recession has stripped out more jobs and taken longer to recover from than the last.

When new companies do prosper and grow, they don’t tend to employ as many people as they did in the past. The major companies of today employ many fewer workers than the major enterprises of yesteryear.

Number of Employees at Major Companies: Present Day versus Past Years

Company: Amazon

Number of Employees in 2017: 341,400

Company: Walmart

Number of Employees (Year): 1,600,000 (2017)

Company: Apple

Number of Employees in 2017: 80,000

Company: GM

Number of Employees (Year): 660,977 (1964)

Company: Google

Number of Employees in 2017: 57,100

Company: AT&T

Number of Employees (Year): 758,611 (1964)

Company: Microsoft

Number of Employees in 2017: 114,000

Company: IBM

Number of Employees (Year): 434,246 (2012)

Company: Facebook

Number of Employees in 2017: 20,658

Company: GE

Number of Employees (Year): 262,056 (1964)

Company: Snap

Number of Employees in 2017: 1,859

Company: Kodak

Number of Employees (Year): 145,000 (1989)

Company: Airbnb

Number of Employees in 2017: 3,100

Company: Hilton Hotels

Number of Employees (Year): 169,000 (2016)

The companies of the future simply don’t need as many people as the companies of earlier eras, and more of their employees have specialized skills.

If one looks at the numbers they clearly show an economy that is having a harder time creating new jobs at previous levels. They also show stagnant median wages, high corporate profitability, low returns on labor, and high inequality, all of which one would expect if technology and automation were already transforming the economy in fundamental ways. As MIT professor Erik Brynjolfsson puts it: “People are falling behind because technology is advancing so fast and our skills and our organizations aren’t keeping up.”

The winner-take-all economy has set us up for what’s coming. But rather than recognize the extent to which economic value is diverging more and more from human time and labor, we essentially keep pretending it’s the 1970s. We’ve been able to get away with this pretense for a few decades by loading up on debt and cheap money and putting off future obligations. That has run its course just as technology is really set to take off and render more of our labor obsolete, particularly for normal Americans.

You might be wondering at my choice of terminology in “normal Americans”—we’ll explore that next.