FOUR

WHAT WE DO FOR A LIVING

I recently emailed a friend, David, to schedule a meeting. When David replied, he copied in another recipient, Amy Ingram, who I assumed was his assistant. Here is the email I got from Amy:

Amy Ingram <amy@x.ai> | Jan. 12 |

Hi Andrew,

Happy to get something on David’s calendar.

Does Tuesday, Jan 17 at 8:30 AM EST work? Alternatively, David is available Tuesday, Jan 17 at 2:00 PM EST or Wednesday, Jan 18 at 10:30 AM.

David likes Brooklyn Roasting Company, 25 Jay St, Brooklyn, NY 11201, USA, for coffee.

Amy

Amy Ingram | Personal Assistant to David

x.ai—an artificially intelligent assistant that schedules meetings

I responded and then got a calendar invite. Only days later did I register that “Amy Ingram” was a chatbot and that x.ai was a tech company. Laughing, David told me that he’d once scheduled a meeting with someone else who was using the same service. The two bots emailed each other repeatedly to hash out a time.

Of course, assistants do more than schedule meetings. They draft correspondence, conduct research, remind you of deadlines, sit in on calls and meetings, and do many other tasks. But increasingly all of these tasks are going to be the domain of cloud-based artificial intelligence.

The rise of the machine that makes human work obsolete has long been thought to be science fiction. Today, this is the reality we face. Although the seriousness of the situation has not reached the mainstream yet, the average American is in deep trouble. Many Americans are in danger of losing their jobs right now due to automation. Not in 10 or 15 years. Right now.

Here are the standard sectors Americans work in:

Largest Occupational Groups in United States (2016)

Occupational Group: All

Total Number Employees: 140,400,040

Percentage of Workforce: 100.00%

Mean Hourly Wage: $23.86

Median Hourly Wage: $17.81

Occupational Group: Office and Administrative Support

Total Number Employees: 22,026,080

Percentage of Workforce: 15.69%

Mean Hourly Wage: $17.91

Median Hourly Wage: $16.37

Occupational Group: Sales and Retail

Total Number Employees: 14,536,530

Percentage of Workforce: 10.35%

Mean Hourly Wage: $19.50

Median Hourly Wage: $12.78

Occupational Group: Food Preparation and Serving

Total Number Employees: 12,981,720

Percentage of Workforce: 9.25%

Mean Hourly Wage: $11.47

Median Hourly Wage: $10.01

Occupational Group: Transportation and Material Moving

Total Number Employees: 9,731,790

Percentage of Workforce: 6.93%

Mean Hourly Wage: $17.34

Median Hourly Wage: $14.78

Occupational Group: Production

Total Number Employees: 9,105,650

Percentage of Workforce: 6.49%

Mean Hourly Wage: $17.88

Median Hourly Wage: $15.93

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor, Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) Survey, May 2016.

Sixty-eight million Americans out of a workforce of 140 million (48.5 percent) work in one of these five sectors. Each of these labor groups is being replaced right now.

CLERICAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF

This is the most common occupational group. McKinsey suggests that between 64 and 69 percent of data collecting and processing tasks common in administrative settings are automatable. Google, Apple, and Amazon are investing billions in artificial intelligence (AI) administrative assistants that can replace these jobs. Many of the settings for these jobs are large corporates that, during the next downturn, will replace headcount with a combination of software, bots, and AI.

Consider that 2.5 million of the jobs in the clerical and administrative category are customer service representatives. They are typically high school graduates making $15.53 an hour or $32,000 a year in call centers.

We’ve all had crummy experiences with voice recognition software and pounded our phone keys until we got a human on the line. But the AI experience is about to improve to a point where we’re not going to be able to tell the difference. Several companies right now employ a hybrid approach where voice recordings are combined with a human in the Philippines tapping buttons so that a Filipino can “call” you but you think you’re talking to a native speaker because you’re hearing a prerecorded voice. This is called accent-erasing software. Soon, it will be an AI hitting the buttons and our ability to distinguish between a call from a bot and a person will disappear.

Rob LoCascio, the founder and CEO of LivePerson, which manages customer service for thousands of businesses, is one of the leading authorities on call centers as the inventor of web chat technology. LivePerson just started rolling out “hybrid bots” for clients like Royal Bank of Scotland; a customer can be passed between a bot and a human and back again depending on the set of issues. Rob estimates that 40–50 percent of tasks performed in customer care are ripe for automation today based on existing technology. He foresees an “automation tsunami” that will leave “tens of millions of workers stranded, with curtailed employment prospects… a hereditary shockwave of economic hardship that could be felt for generations.” He notes that most of the affected people are “likely to be in lower income brackets without the luxury of time to re-train… and without the savings to invest in re-education.” When the CEO of a company called LivePerson says that about the prospects of human workers in his industry, that’s a pretty terrible sign.

I met with a technologist who works with one of the major financial institutions. He estimated that 30 percent of the bank’s home office workers—more than 30,000 employees—were engaged in clerical tasks transferring information from one system to another, and he believed that their roles would be automated within the next five years. I had a similar conversation with a friend at another bank who told me that many of the people in the San Francisco homeless shelter he volunteers at used to work in clerical roles that are no longer necessary, and that his bank was similarly downsizing back office and clerical workers in large numbers.

Some argue that it will be possible to automate only a portion of each person’s job. But if you have a department of 100 clerical workers and you find that 50 percent of their work can be automated, you fire half of them and tell the remaining workers to adjust. And then you do it again the next year. Clerical tasks are almost always cost centers, not growth drivers. Office and administrative support jobs are going to disappear by the tens of thousands into the cloud as offices become increasingly more automated and efficient.

SALES AND RETAIL

We’ve all gone to our local CVS to be greeted by a self-serve scanner at the end. There’s only one employee, the troubleshooter, where there used to be two or three cashiers. This is the case where local stores still exist—a lot of them are closing outright.

About 1 in 10 American workers work in retail and sales, with 8.8 million working as retail sales workers. They have an average income of $11 per hour, or $22,900 per year. Many have not graduated from high school, yet their median age is 39. Sixty percent of department store workers are female.

The year 2017 marked the beginning of what is being called the “Retail Apocalypse.” One hundred thousand department store workers were laid off between October 2016 and May 2017—more than all of the people employed in the coal industry combined. Said the New York Times in April 2017, “The job losses in retail could have unexpected social and political consequences, as huge numbers of low-wage retail employees become economically unhinged, just as manufacturing workers did in recent decades.”

Wall Street analysts have deemed the entire sector borderline uninvestable. Dozens and soon hundreds of malls are closing as their anchor stores—JCPenney, Sears (soon to be bankrupt), and Macy’s—close dozens of locations. Among the chains that have declared bankruptcy recently are Payless (4,496 stores), BCBG (175 stores), Aeropostale (800 stores), Bebe (180 stores), and the Limited (250 stores). As of 2017, those in danger of default include Claire’s (2,867 stores), Gymboree (1,200 stores), Nine West (800 stores), True Religion (900 stores), and other fixtures that may be bankrupt or defunct by the time you read this. Credit Suisse estimated that 8,640 major retail locations will close in 2017, the highest number in history, exceeding the 2008 peak during the financial crisis. Credit Suisse also estimated that as many as 147 million square feet of retail space will close in 2017, another all-time high. For reference, the Mall of America is the biggest mall in the country, at 2.8 million square feet. The equivalent of 52 Malls of America are closing in 2017, or one per week.

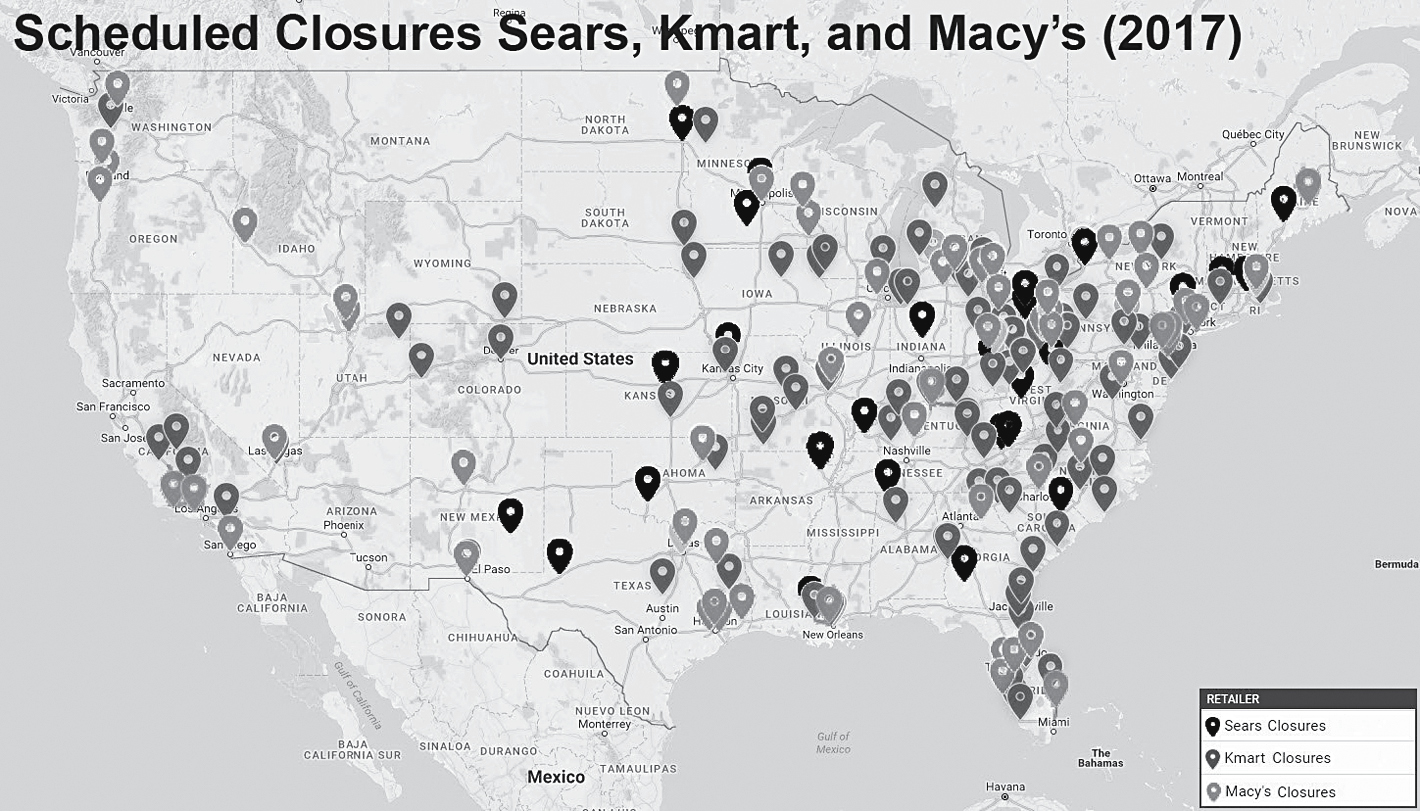

CoStar, a commercial real estate firm, estimated in 2017 that roughly 310 out of the nation’s 1,300 shopping malls are at high risk of losing an anchor store, which typically begins a mall’s steep decline. Another retail analyst predicted that 400 malls will fail in the next few years and that 650 of the remaining 900 malls will struggle to stay open. Here’s a map of scheduled Macy’s, Sears, and Kmart closures as of 2017:

I grew up going to my local mall in Yorktown Heights, New York. It represented the height of many things to me at the time—commerce, culture, freedom, status. I would stake out a few clothing items and wait for them to go on sale. Buying a thing or two would give me joy. I would run into classmates at the mall, for good or ill. That time is gone for good in much of the country.

When a mall closes or gets written down, there are many bad things that happen to the local community. First, many people lose their jobs. Each shuttered mall reflects about one thousand lost jobs. At an average income of $22K, that’s about $22 million in lost wages for a community. An additional 300 jobs are generally lost at local businesses that either supply the mall or sell to the workers.

It gets worse. The local mall is one of the pillars of the regional budget. The sales tax goes straight to the county and the state. And so does the property tax. When the property gets written down, the community loses a big chunk of tax revenue. This means shrunken municipal budgets, cuts to school budgets, and job reductions in local government offices. On average, a single Macy’s store generates about $36 million a year. At current sales tax and property tax rates, that store, if closed, would leave a budget hole of several million dollars for the state and county to deal with.

If you’ve ever been to a dead or dying mall, you know that it’s both depressing and eerie. It’s a sign that a community can’t support a commercial center and that it may be time to leave. It’s not just you. Dying malls become havens for crime. One declining Memphis-area mall reported 890 crime incidents over several years. “Cars are keyed randomly in mall parking lots, and there is not enough security to provide the level of safety a family wants while they are at the mall,” said one local resident. In Akron, a dying mall was the site of a man’s electrocution death when he was trying to steal copper wire, while a homeless man was sentenced to prison for living inside a vacant store. The mayor of Akron eventually instructed residents to “stay clear of the area” before the mall was targeted for demolition.

Ghost malls are an example of what I call negative infrastructure. The physical structure of a mall has immense value if there is commerce and activity within. If there isn’t, it can very quickly become a blight on a community. It reminds me of when I first visited Detroit and its surrounding suburbs at the bottom of their decline. You could see all the hallmarks of people leading lives in a once-thriving economy—hair salons, day care centers, coffee shops, and so on—but as the economy decayed, people left and businesses closed. The value of all of those buildings, storefronts, and homes went from hugely positive to hugely negative. Unused infrastructure decays quickly and gives an environment a bleak, dystopian atmosphere, like a zombie movie set. I’m glad to say that Detroit has gotten a lot better since 2011.

There have been heroic efforts to repurpose malls in innovative ways—churches, office parks, recreation centers, medical offices, experiential retail, even public art spaces. There’s a giant mall outside San Antonio that the web hosting company Rackspace has turned into its corporate headquarters; it’s amazing to visit. But for every successful adaptation, there are going to be 10 others that lie vacant in disuse and become crime-ridden shells that reduce property value for miles around.

Why are so many malls and stores closing? Developers may have built too many of them. But the main cause is the rise of e-commerce. Particularly Amazon. Amazon now controls 43 percent of total e-commerce in the United States. It has a market capitalization of $435 billion. Overall, e-commerce has been rising by $40 billion a year since 2015, which is now pushing traditional retail into extinction. Amazon just bought Whole Foods to expedite their move into grocery delivery. Most everyone I know buys a lot of stuff on Amazon. It is virtually impossible for any brick and mortar retailer to compete against Amazon on price. This is because Amazon doesn’t have to invest in storefronts and can focus on building an efficient delivery system at the highest volumes.

Here’s their other advantage—Amazon doesn’t even need to make money. In its 20 years as a public company, Amazon often has not turned a profit. A number of years ago, some financial types noticed and shorted the stock, saying, “Amazon doesn’t make money.” In response, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos stopped investing in anything new for a year and ramped up profitability. The people betting against the stock were burned badly. Now, no one bets against Amazon, and its stock price is over $900 per share, making Jeff one of the richest people in the world. Jeff is dedicating $1 billion of his personal wealth to his space exploration company, Blue Origin, each year. A friend of his joked to me that “we’ll get Jeff to care about what happens on this planet one of these days.”

Amazon is known for its competitive—some might even say ruthless—practices. In 2009, they were trying to push Diapers.com to the negotiating table, so they discounted diapers to a point where no one was making money. It worked and they bought Diapers.com for $545 million a little while later.

I don’t think Jeff Bezos has it out for local malls, per se. But there will nonetheless be hundreds of thousands of people who suffer from the demise of retail, driven by e-commerce giants like Amazon: the mall workers, the people who liked shopping at the mall, the county workers who needed the mall’s property tax to pay for their jobs, the property owners near the mall, and so on. Hundreds of our communities are going to have giant holes blasted in them by progress that will disrupt thousands of lives and livelihoods in each. And the victims are likely to be among the weakest in the labor market—retail workers are paid less than workers in most other industries and typically lack a college degree. Where are they going to go?

It’s not just the malls—little shops and restaurants everywhere are closing. You’re probably seeing empty storefronts around where you live and work right now.

A New York Times op-ed by the economic historian Louis Hyman detailed the plight of towns in upstate New York and other places that have seen their retail sectors decline and offered some recommendations for how workers could readjust to the new economic reality:

Main Street… exists, but only as a luxury consumer experience… If the answer to rural downward mobility is to turn everyone into software engineers, there is no hope… Today, for the first time, thanks to the internet, small-town America can pull back money from Wall Street (and big cities more generally). Through global freelancing platforms like Upwork, for example, rural and small-town Americans can find jobs anywhere in the world, using abilities and talents they already have. A receptionist can welcome office visitors in San Francisco from her home in New York’s Finger Lakes. Through an e-commerce website like Etsy, an Appalachian woodworker can create custom pieces and sell them anywhere in the world.

This op-ed is a great summary of the general constructive thinking. It recognizes that the retail sector will shrink and happily debunks the ridiculous “let’s turn everyone into coders” idea, which is realistic for only a tiny proportion of displaced workers. If you dig into the author’s alternative suggestions for workers though, they’re equally unrealistic and could only be offered by someone who hadn’t tried any of them. Upwork primarily finds work for developers, designers, and creatives on a global scale. Asking a retail worker from small-town America to log on and get work assumes they have a skill to offer. These global platforms have people offering their services from abroad, who can price their time at as little as $4 an hour even for a college graduate. Getting work on these platforms is highly competitive, doesn’t pay very well, and carries no benefits.

Offices in San Francisco have either iPads or human beings as receptionists. They don’t have avatars staffed by human beings in small towns hundreds of miles away. Selling woodwork on Etsy is the kind of thing that would work for a handful of humans and is unlikely to feed your family. On average, sellers’ income from Etsy contributes only 13 percent to their household income and is intended as a supplement to traditional work. Forty-one percent of Etsy sellers who focus on their business full-time get their health care through a spouse or partner, and 39 percent are on Medicare or Medicaid or another state-sponsored program.

It’s possible that some workers in towns with dying retail stores could find menial jobs on their computers as telemarketers, phone sex operators, English tutors to Chinese kids, or image classifiers to help train AI. That’s not exactly an appealing future though—and long-distance low-skilled jobs are the ones most subject to automation and a race to the lowest-cost provider. Most retail workers at least had the gratification of leaving home, conversation with colleagues and customers, getting a store discount, and generally being a member of society.

The reason that even well-meaning commentators suggest increasingly unlikely and tenuous ways for people to make a living is that they are trapped in the conventional thinking that people must trade their time, energy, and labor for money as the only way to survive. You stretch for answers because, in reality, there are none. The subsistence and scarcity model is grinding more and more people up. Preserving it is the thing we must give up first.

FOOD PREPARATION AND SERVICE

For the number three job in America, the median hourly wage is $10 an hour with an annual average wage of $23,850. Most of these workers have not attended college. Food service and food prep workers are not in immediate danger of replacement to the same degree as are call center workers and retail workers. Mom-and-pop restaurants are not changing their practices anytime soon, and food service workers are generally so inexpensive that the incentives to replace them are modest. The restaurant industry is facing headwinds due to lower foot traffic in many places, more lunches eaten at desks (the “lunch depression”), high levels of competition, the decline of mid-price restaurants, and the rise of eat-at-home delivery services like Blue Apron, but people anticipate restaurants holding up better than traditional retail.

Still, change is brewing. I had brunch with a venture capitalist friend in San Francisco. She told me an important story: “A company came to me with a software product that helps fast food workers get scheduled for shifts more efficiently among multiple locations. Any given worker could be optimally assigned a shift across several nearby stores. It seemed like a good idea. But when I went to a couple fast food companies and I asked them if they would use this kind of software, their response was, ‘We’re not trying to schedule our workers more efficiently. We’re trying to replace them altogether.’ So I didn’t invest in that company. Instead, I invested in a couple companies that make smoothies and pizza with robots and delivery.”

She’s not alone. There is now a mechanized barista in a lobby in San Francisco. It’s named Gordon. You can text in your order and the robot can be set up in most any location. I tried it and my Americano was delicious, for about 40 percent less than at Starbucks. Gordon provides a more efficient, cheaper, and equally high-or even higher-quality product than a human barista. In the morning, when you are running late to work and all you want is a quick cup of coffee, these pluses will be valuable. After Gordon debuted, Starbucks was forced to issue a statement saying that it didn’t plan on replacing its 150,000 baristas.

Some workers will be easier to replace than others. For instance, we all like fast food drive-thru restaurants for their efficiency and do not mind the limited human interaction. In fact, 50 to 70 percent of fast food sales take place at drive-thru windows in the United States—McDonald’s being the one that most of us know and (used to) love. There are 1–2 workers per location who take the order through the speaker—they wear those cool headsets. These workers will be replaced by software in many locations in the next five years. Publicly traded fast food chains will be among the most aggressive adopters of increased efficiencies because they have the scale, resources, and quarterly earnings pressures to maximize shareholder returns. McDonald’s just announced an “Experience of the Future” initiative that will replace cashiers in 2,500 locations to start. The former CEO of McDonald’s suggested that large-scale automation is around the corner. “It’s cheaper to buy a $35,000 robotic arm than it is to hire an employee who’s inefficient making $15 an hour bagging French fries,” he said while defending the current prevailing fast food wage of $8.90. The robot arm is only going to get cheaper and more efficient, while the fast food wage has no place to go but up. Approximately 4 million workers work in fast food.

If you’ve been through an airport recently, you might have noticed restaurants that have replaced servers with iPads. Eatsa, a recently opened restaurant chain, has a whole row of iPads for you to enter the order, and then a series of lockers where your food appears. They’ve gotten rid of all of the front-of-house workers. Eatsa was recently named one of the most influential brands in the restaurant industry, and it’s here to stay. All it takes is a few chains to bite the bullet and enjoy labor-free efficiencies and the others will follow quickly. McKinsey estimates that 73 percent of food prep and service activities are automatable.

On the production end, you can now use a 3D printer to make hot pizza in five minutes that can be customized to particular orders. BeeHex’s bot, called the Chef 3D, will appear at select theme parks and sports arenas starting later this year. Just like the robot barista, Chef 3D is faster, cleaner, and more reliable than human workers. Only one person is needed to work the machine, which can mix the composition and lay down the sauce and the toppings in one minute. Apparently it tastes great. No more person in the back making pizzas by the oven. There are companies now launching that are essentially pizzerias on wheels, where they make the pizza in special trucks on their way to you in anticipation of your order.

For the last mile, there are now food delivery robots being used in Washington DC, and San Francisco. They are essentially coolers on wheels that deliver food to your door for around a dollar. One company called Starship Technologies has 20 or so robots deployed that are already learning their local terrain in Washington, DC, which has officially made self-driving robots legal on its sidewalks. These robots will eliminate the need for many deliverypeople.

A friend of mine, Jeff Zurofsky, ran a chain of sandwich shops for a number of years. He said to me, “Our biggest operational issue is that sometimes people just don’t show up to work. We pay significantly over the minimum wage, but employee reliability is a recurring problem.”

Food prep and service jobs are going to remain numerous for a while to come because of low costs and industry fragmentation. But fundamentally, most of the tasks are highly repetitive and automatable. Companies with resources are going to continue to experiment with new ways to reduce costs and we will see fewer and fewer workers in many restaurants over time. Also, as regional economies weaken, restaurants in those regions will struggle and close.

Clerical jobs, retail jobs, and food service jobs are the most common jobs in the country. Each category is in grave danger and set to shrink dramatically. Yet they’re not even the ones to worry about most. The single most defining job in the automation story—the one that scares even the most hard-nosed observer—is the number four job category: materials transport, also known as truck driving.