THIRTEEN

THE PERMANENT SHADOW CLASS: WHAT DISPLACEMENT LOOKS LIKE

In 2015, husband-and-wife economic researchers Anne Case and Angus Deaton found that mortality rates had increased sharply and steadily for middle-aged white Americans after 1999, going up 0.5 percent per year. They figured they must have made a mistake—it’s more or less unheard of in a developed country to have life expectancy go down for any group for more than a momentary blip. Said Deaton: “[W]e thought it must be wrong… we just couldn’t believe that this could have happened, or that if it had, someone else must have already noticed.”

As it turns out, yes, it had happened, and yes, no one had noticed.

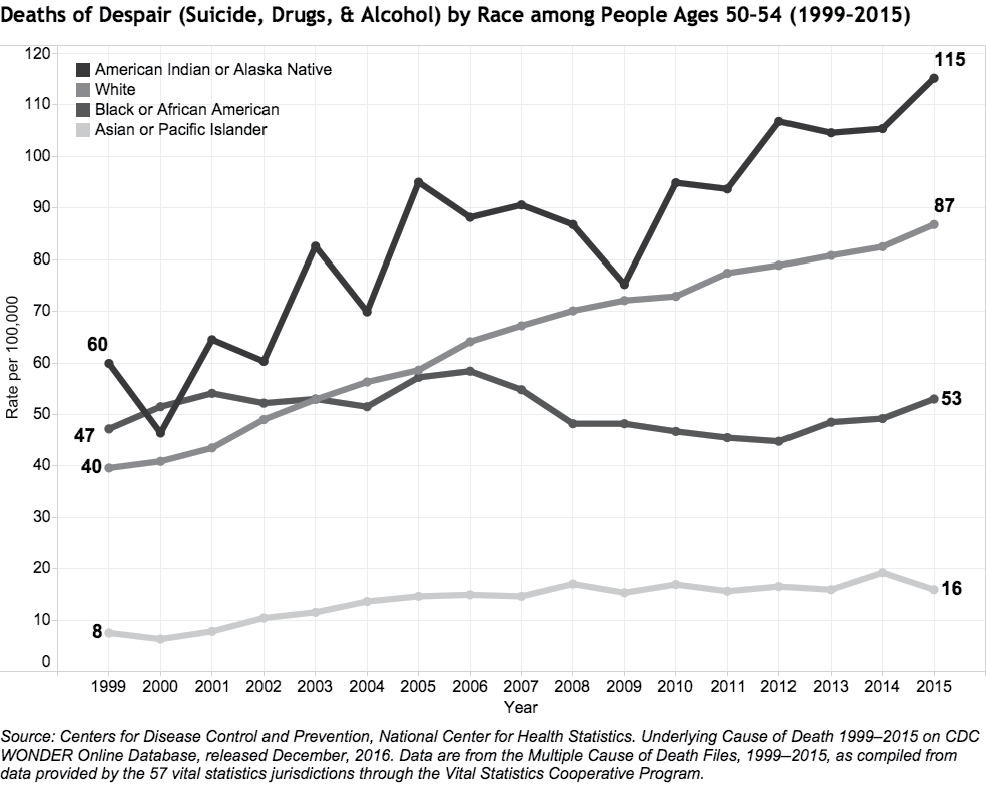

As Case and Deaton found, suicides were way up. Overdoses from prescription drugs were much higher. Alcoholic liver disease was commonplace. Historically, African Americans have had higher mortality rates and shorter life expectancies than whites. Now, whites with a high school degree or less have the same mortality rates as African Americans with the same levels of education. What was behind the disturbing trends?

Case and Deaton point the finger at jobs. Deaton explained, “[J]obs have slowly crumbled away and many more men are finding themselves in a much more hostile labor market with lower wages, lower quality and less permanent jobs. That’s made it harder for them to get married. They don’t get to know their own kids. There’s a lot of social dysfunction building up over time. There’s a sense that these people have lost this sense of status and belonging… these are classic preconditions for suicide.” They noted that the higher mortality rates and deaths of despair applied equally to middle-aged men and women in their study, though men experience these at much higher levels.

Many of the deaths are from opiate overdoses. Approximately 59,000 Americans died of drug overdoses in 2016, up 19 percent from the then-record 52,404 reported in 2015. For the first time, drug overdoses have surpassed car accidents as the leading cause of accidental death in the United States. Coroners’ offices in Ohio have reported being overwhelmed as the number of overdose victims has tripled in two years in some areas—they now call nearby funeral homes for help with storage.

The five states with the highest rates of death linked to drug overdoses in 2016 were West Virginia, New Hampshire, Kentucky, Ohio, and Rhode Island. Over 2 million Americans are estimated to be dependent on opioids, and an additional 95 million used prescription painkillers in the past year, according to the latest government report—more than used tobacco. In 12 states there are more opioid prescriptions than there are people. Addiction is so widespread that in Cincinnati hospitals now require universal drug testing for pregnant mothers because 5.4 percent of mothers had a positive drug test in past years. “Opioids are what we worry about most,” explained Dr. Scott Wexelblatt, a neonatologist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Perinatal Institute.

People often think of opioid addiction as originating with prescription painkiller use. OxyContin hit the market in 1996 as a “wonder drug,” and Purdue Pharma, which was fined $635 million in 2007 for misbranding the drug and downplaying the possibility of addiction, sold $1.1 billion worth of painkillers in 2000—a sum that climbed to a staggering $3 billion in 2010. The company spent $200 million in marketing in 2001 alone, including hiring 671 sales reps who received success bonuses of up to almost a quarter million dollars for hitting sales goals. An army of drug dealers in suits marketed addictive opioids to doctors, getting paid hundreds of thousands to do it. Regarding OxyContin, CDC director Dr. Tom Frieden noted that “we know of no other medication routinely used for a nonfatal condition that kills patients so frequently.” A study showed that one out of every 550 patients started on opioid therapy died of opioid-related causes a median of 2.6 years after their first opioid prescription.

Now many opioid users have graduated to heroin. One common pattern of addiction is that people use prescription painkillers for pain relief or recreationally as a party drug—they grind up pills and sniff them for a euphoric high that lasts for hours. Then they later switch to heroin, which opioid users cited as more easily obtainable. A study conducted by the New England Journal of Medicine showed that 66 percent of those surveyed switched to other opioids after using OxyContin.

The majority of heroin users used to be men. However, because women are prescribed opioids at higher rates, today the gender balance of heroin users is about 50-50. Ninety percent of heroin users are white.

“We are seeing an unbelievably sad and extensive heroin epidemic, and there is no end in sight,” says Daniel Ciccarone, a medical doctor at the University of California at San Francisco who studies the heroin market. “We are not, in 2017, anywhere close to the top of this thing. Heroin has a life force of its own.” Drug cartels have begun to sell heroin laced with fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that increases both the high and the addiction level and is cheaper than heroin, and carfentanil, an elephant tranquilizer so powerful that simply touching it can cause an overdose when it is absorbed through the skin.

Our drug companies and medical system have produced hundreds of thousands of opioid addicts who are now heroin users buying from dealers. Heroin dealers have become ubiquitous—Ohio police say they’ve seen dealers text their customers to advertise two-for-one Sunday specials and offer free samples set up on car hoods in a local park. Some dealers have scheduled business hours. Others throw “testers” wrapped in paper slips printed with their phone number into passing cars, hoping to hook new business. Said Detective Brandon Connley after arresting a low-level dealer in Ohio, “Everybody and their mom sells drugs these days. There’s always somebody right there to pick back up.” Many dealers are addicts themselves trying to keep a steady supply.

This opioid plague will be with us for years in part because treatment is so difficult. Heroin and opioids are notoriously difficult addictions to break. Withdrawal symptoms include cravings, nausea, vomiting, depression, anxiety, insomnia, and fever. Most people relapse several times on their way to recovery, and many are forced to use opiate substitutes like methadone to manage their addiction. Only about 10 percent of people that had a drug abuse disorder received appropriate treatment, according to a 2014 study. Most people can’t break the habit on their own and require extended rehabilitation. Sally Satel, a doctor and professor who has treated heroin users for years, said, “I speak from long experience when I say that few heavy users can simply take a medication and embark on a path to recovery. It often requires a healthy dose of benign paternalism and, in some cases, involuntary care through civil commitment.” Treatment centers cost between $12,000 and $60,000 for 30-to 90-day inpatient care, with outpatient 30-day programs starting around $5,000, with no assurance of success.

Hand-in-hand with the spike in suicides and addiction has been the incredible increase in applications to Social Security disability programs. Almost 9 million working-age Americans receive disability benefits. That’s more than the entire population of New Jersey or Virginia. The percentage of working-age Americans who received disability benefits was 5.2 percent in 2017, up from only 2.5 percent in 1980. Disability applications started surging in 2000, the same year that manufacturing employment started to plummet. The average benefit size in June 2017 was $1,172 per month, at a total cost of about $143 billion per year. The age of the disabled has gone down—in 2014, 15 percent of men and 16.2 percent of women in their 30s or early 40s were on disability, up from 6.6 percent and 6.4 percent in the 1960s.

Rates of disability track areas of joblessness, forming “disability belts” in Appalachia, the Deep South, and other regions. In a couple of counties in Virginia, fully 20 percent of working adults ages 18–64 are now receiving disability benefits. West Virginia, Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, and Mississippi are the top five states for disability beneficiaries, with 7.9–8.9 percent of the workforce receiving income replacement. Disability payments received by beneficiaries in these five states exceed $1 billion per month. In these areas, disability benefits are so widespread that the day that checks arrive is like a monthly holiday. Said one West Virginian who processed disability claims, “They’re a vital part of our economy. A lot of people depend on them to survive. [On the days checks arrive] you avoid the pharmacy. You avoid Wal-Mart. You avoid, you know, restaurants… Everybody’s received their benefits. Let’s go shopping.”

Some of the increasing rates of disability reflect an aging population and changing demographics. But many of them represent what one expert called “economic disability.” The biggest growth categories of disability are “mental disorders” and “musculoskeletal and connective tissue,” which together now comprise about 50 percent of disability claims, nearly double what they were 20 years ago. These diagnoses are also the hardest to independently verify for a doctor.

The number of people who applied for disability benefits in 2014 was 2,485,077. On any given business day, there are 9,500 applicants. There are 1,500 disability judges around the country who administer the decisions, often without seeing the claimants. The waiting period to get a hearing is now more than 18 months in most states. To apply for disability, applicants must gather evidence from medical professionals. They compile notes from doctors, send in the information, and wait to hear back. No lawyer representing the government cross-examines them. No government doctor examines them. About 40 percent of claims are ultimately approved, either initially or on appeal. The lifetime value of a disability award is about $300K for the average recipient.

Because the stakes are so high, representing claimants has become a big business. Law firms regularly advertise for clients on late-night television to help them navigate the process and collect a fee, typically a percentage of the award. Eighty percent of appealing claimants are represented by counsel, up from less than 20 percent in the 1970s. One law firm generated $70 million in revenue in one year alone from representing disability claimants.

After someone is on disability, there’s a massive disincentive to work, because if you work and show that you’re able-bodied, you lose benefits. As a result, virtually no one recovers from disability. The churn rate nationally is less than 1 percent. David Autor asserts that Social Security Disability Insurance today essentially serves as unemployment insurance around the country. It’s not designed for this, but that’s what it is for hundreds of thousands of Americans.

One judge who administers disability decisions said that “if the American public knew what was going on in our system, half would be outraged and the other half would apply for benefits.”

I spoke to a friend, Tony, about his experience applying for disability. He and I grew up together playing Dungeons and Dragons on the same street. Tony is a house painter who worked previously as a musician and sound technician. He was married briefly but is now divorced. Tony finished his college degree a few years ago at a public university. He went most of his childhood without health insurance—his father was a contractor and self-employed. In 2011, he moved to western Massachusetts and received health insurance for the first time—it was free under “Romneycare” because he was considered low income.

A couple years ago, after not being able to work for a few months due to health problems, Tony was told by his therapist, “You should try to get disability.” Tony at first thought that he wouldn’t qualify because his injuries were mostly brain-related: multiple traumatic brain injuries from childhood accidents (a fall on concrete when he was nine and a crashed scooter when he was 11) and concussions from playing high school football led to impaired cognition and mood swings. He also suffered from chronic fatigue, muscle pain, depression, and chronic Lyme disease.

Tony took the therapist’s advice and went on the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) website to apply. He submitted notes from his therapist, nurse prescriber, supervising psychiatrist, primary care physician, a specialist in holistic medicine, and a specialist in infectious disease. “I had a lot of stuff that had built up in my body over the years. I sometimes think that if I’d had proper treatment as a kid I might not be disabled today.” Tony submitted the paperwork in March 2016 and was notified that he was denied benefits five months later. About 75 percent of initial claims get denied nationally. He then went online and found a local attorney who specializes in disability appeals. The lawyer worked through the appeals process on Tony’s behalf. Two months later, Tony was approved and began receiving approximately $1,200 a month. “After the lawyer took over, that was it. The money showed up in my account.” The lawyer collected about $2,700 for handling the appeal—25 percent of the disability payments that were retroactive to when Tony was deemed disabled.

Tony is currently on disability, and his first review will be after two years. “Thank God for disability. If not for disability I would have worked myself to death and died.” Tony is 42. He volunteers at a local church. “I live in western Massachusetts, which is not someplace that people think of as struggling. But it’s crazy how many people come in to church who are living in tents and on the street. People just do what they have to do to get by.”

I’m personally very glad that disability was there for Tony. For him, disability was literally a lifesaver.

J. D. Vance writes of how the people in Ohio became angry that they were working hard and scraping by while others were doing nothing and living off of government checks. He cites this resentment toward government handouts as an explanation for why regions like Ohio have become more Republican.

The numbers have grown to a point where more Americans are currently on disability than work in construction. In 2013, 56.5 percent of prime-age men 25–54 who were not in the workforce reported receiving disability payments. Though the numbers have stabilized as more people in this age group have moved into Social Security retirement, they are already way beyond what anyone intended. The fund for disability insurance recently ran out and was combined with the greater Social Security fund, which is itself scheduled to run out of money in 2034.

The fact that a program designed for a relatively small number of Americans has now become such a major lifeline for people and communities is part of the Great Displacement. We pretend that our economy is doing all right while millions of people give up and “get on the draw” or “get on the check.” It’s a $143 billion per year shock absorber for the unemployed or unemployable, whose ranks are growing all of the time. After one gets on disability, one enters a permanent shadow class of beneficiaries. Even if you start feeling better, you’re not going to risk a lifetime of benefits for a tenuous job that could disappear at any moment. And it’s likely easier to think of yourself as genuinely disabled than as someone cheating society for a monthly draw.

Many Americans, disabled or not, have some degree of health problems. If you’ve got a good job, you might ignore your hurt back or, if your job offers health insurance, have access to an affordable way to treat it and continue working. If you don’t have a job and the stress starts to mount, you can easily start to feel more infirm. This is doubly true in environments where work is mostly manual and involves a lot of wear and tear. For many, the chain of circumstances is to go from former manufacturing worker to disability recipient. The other major refuge has been retail jobs. After these jobs disappear, the ranks of the disabled will swell.

Disability illustrates the challenges of mandating the government to administer such a large-scale program. It’s essentially the worst of all worlds, as the truly disabled and needy may find themselves shut out by red tape, while the process rewards those who lawyer up and the lawyers themselves. It sends a pervasive message of “game the system and get money” and “think of yourself as incompetent and incapable of work.” It’s subject to fraud. And once you’re on, you never leave.