In the first issue of Der Dada Raoul Hausmann wrote, “The masses couldn’t care less about art or intellect. Neither could we.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, given comments like this, Dada has been pegged as an anti-art movement; to wit, Hans Richter’s classic study was titled Dada, Art and Anti-Art. But the truth is more complicated.

What the Berlin Dadaists had in common (most of them being artists, after all) was their disdain for art institutions like the academies, juries, dealers, and complicit art stylists who promoted an elitist mystification of Kunst und Kultur (art and culture). The Berlin Dadaists repudiated the art racket, monopolized by “the professional arrogance of a haughty guild,” observed Herzfelde. The kaiser patronized the most conservative art, casting over even French Impressionism an aura of ill repute. The Dadaists regarded such patronage as part of a larger delusion evident in German glorification of the military. Conventional art, from the Dadaist perspective, amounted to “a large-scale swindle” and “a moral safety valve.” “Dada is forever the enemy of that comfortable Sunday Art which is supposed to uplift man by reminding him of agreeable moments,” Huelsenbeck wrote, adding “Dada hurts” to drive the point home.

An example of Dada’s rapier wit and its sting is evident in an article penned by Heartfield and Grosz. “The Art Scab” denounced Expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka’s lament that during the Sparticist uprising a stray bullet had struck a Rubens painting in the Zwinger Museum in Dresden. “The Art Scab” reads like the snarl of a rabid hound with teeth bared and fur bristling, exhorting fellow citizens to beware of the “fangs of the bloodsuckers” like Kokoschka. “We summon all to oppose the masochistic reverence for historical values,” Heartfield and Grosz cried, “to oppose culture and art!”

The title “artist” is an insult.

The designation “art” is an annulment of human equality.

The deification of the artist is equivalent to self-deification.

The artist does not stand above his milieu and the society of those who approve of him. For his little head does not produce the content of his creations, but processes (as a sausagemaker does meat) the worldview of his public.

The concision and clarity of these remarks is meant to cut, leave a raw mark on the mind like the dueling scars famous among the Prussian military caste. But it’s also meant in deadly earnest.

Der Blutige Ernst, the title of a journal published by Herzfelde at Malik, translates as “bloody serious.” The journal’s pages boiled over with Grosz’s barbed cartoon sketches. Their stance was explicit and confrontational: “There is no longer room for pretty scribblings and idolization of form.” Such artistic niceties had, the Dadaists argued, been complicit in the downfall of Western civilization. In the words of Herzfelde’s prospectus, “Der blutige Ernst nails down the maladies of Europe, it records the utter collapse of the continent, fights the deadly ideologies and institutions which caused the war, establishes the bankruptcy of Western culture.”

Grosz’s calculatedly puerile art had a distinctly political edge, challenging the notion of art as “an aesthetic harmonization of bourgeois ideas of ownership.” Yet Dada wrath was aimed at a closer target. “Who is the German petit bourgeois to be getting cross about Dada?” Hausmann wondered.

It’s the German poet, the German intellectual bursting with rage because the perfect form of his lardy sandwich-soul has been left stewing in the sun of laughter, raging because he was hit right in the middle of his brain, which is what is he sitting upon—and now he has nothing anymore to sit on! No, don’t attack us, gentlemen, we are already our own enemies.

Artists who pandered to this lardy soul were regarded with utter contempt by the Dadaists.

If Grosz intended his doodles as insults, other Dada innovations were less polemical but no less incendiary, simply because of their novel means of production. Hausmann maintained, “The child’s discarded doll, or a colorful rag are more notable expressions than those of some ass who wants to transplant himself in oil forever in the salon.” He preferred “the simultaneous perception and experience of the environment”: that is, enrichment of the perceptual capacity of the individual, not obsequious catering to the money trail of the art market.

Grosz’s sympathies likewise favored the enrichment of perception by any means. For him, the conventional distinction made between fine art and the applied arts was a vestige of the class system. As he developed his expressive style, Grosz’s inspiration came not from the fine arts but from children’s drawings, graffiti, pornography, even kitsch—anything done with personal urgency. These sources helped him develop the means to fit the moment. As philosopher Hannah Arendt attested, his “cartoons seemed to us not satires but realistic reportage: we knew these types; they were all around us.” A type doesn’t need lavish detail to be recognizable. The smug capitalist, the harried prostitute, a war cripple begging on the street: these were the primal figures Grosz sketched time and again.

Grosz’s choice of subjects repeatedly got him into trouble. The first Malik publication of his drawings was confiscated and the plates destroyed by the authorities. He and Herzfelde were fined and later found themselves facing the same charges again: Malik kept publishing and selling Grosz’s unflattering visions in more books and journals.

The most prolonged litigation lasted from 1928 to 1931 in a series of trials and retrials arising from his memorable sketch Christ with Gasmask for Erwin Piscator’s staging of The Good Soldier Schweik. The press branded Grosz a political agitator, Bolshevik, and nihilist—not an artist. But his friend and occasional patron Count Kessler saw through the intimidating façade:

The devotion of his art exclusively to the depiction of the repulsiveness of bourgeois philistinism is, so to speak, merely the counterpart to some sort of secret ideal of beauty that he conceals as though it were a badge of shame. In his drawings he harasses with fanatical hatred the antithesis to this ideal, which he protects from public gaze like something sacred. His whole art is a campaign of extermination against what is irreconcilable with his secret ‘lady love.’

Grosz’s truculent drawings mesmerized his contemporaries. When The Face of the Ruling Class was published in 1921, its 6,000 copies quickly sold out, as did two more printings the same year of 7,000 and then 12,000. It may have seemed “propaganda” to political adversaries, but propaganda sells when its target is clear and its message is recognized and appreciated.

Ben Hecht’s account of his first encounter with Grosz’s drawings in his studio has the snap and crackle that a journalist cum Hollywood screenwriter could summon. Written nearly fifty years later, Hecht sounds like he’s still reeling under the impact:

Fever-thin lines, quaint spurts of ink that seemed to crawl on the paper, tipsy walls, spidery streets, leering windows; a half-ghostly goulash of breasts, buttocks, thighs, drooling mouths, murderous eyes, crafty fat necks, and all the strut and coarseness of the overfed subhumans who ran the German world and sported in its German cafes . . . Grosz, as fine a draftsman as Delacroix, and as disillusioned an eye as Daumier, omitted nine tenths of anatomy and structure from his drawings. The result was a “tenth” full of nightmare. It was life that was being violated. His figures scratched at your eyes. Immorality, heavy lipped and heavy uddered, rolled a bovine eye at army officers and financiers who sat belching aloofly on their large, authoritative rumps. Lust, gluttony, brutality, and all the tricks of wearied evil snickered out of the half humans who kissed and killed one another in a world that looked like a demented strawberry box.

Except for writers Huelsenbeck and Mehring, the Berlin Dadaists did produce artworks, though their contemporaries wouldn’t have called them that. Heartfield became famous (especially as the Nazis rose to power) for his political photomontages, an artistic innovation that the Dadaists pioneered. A Dadaist was not an artist but a monteur, the German word for “mechanic,” and the Dadaists called the work they produced montage, a cognate term for assembly-line work. Photomontage and collage would have a huge effect on global culture in the years to come and would become ubiquitous from the 1960s to the Internet age.

Heartfield and Grosz had started doing cut-and-paste works soon after they met. Höch and Hausmann were also immersed in collage. Baader followed suit. Erwin Blumenfeld, like others only momentarily affiliated with Dada, also excelled at the new technique before he rose to eminence as a fashion photographer. Much ink has been spilled identifying who originated the technique, but in fact the explosion of print material in the nineteenth century stimulated ordinary people to cut and paste without claiming the results as art. Picasso snipped bits of newspaper and glued them onto his paintings during the heyday of Cubism before the war. But it was in the Berlin Dada circle that photomontage took wing, “an explosion of viewpoints and an intervortex of azimuths” in Hausmann’s heady evocation.

In keeping with the new practices, the Dadaists thought of themselves as mechanics or technicians more than artists in the traditional sense. In one of his collages, Grosz included the line “Marshal Grosz Demands Taylor’s System in Painting”—that is, Taylorized production efficiency as in a factory. Grosz had a rubber stamp made, which he used to apply his name to his works in lieu of a signature. Grosz and Heartfield advertised their art in these terms: “Great quality guaranteed in every type of art: expr. futur., dada, meta-mech.” This is a send-up of prevailing styles (Expressionism, Futurism, Dada), of course, but the final term was the Dada favorite, standing for metamechanical production. As Hausmann saw it, “The beauty of our daily life is defined by the mannequins, the wig-making art of the hair stylist, the precision of a technical construction!” Accordingly, “we will have to get accustomed to seeing art originating in workshops.”

A wave of mechanistic painting and drawing swept through Club Dada in late 1919 after the Dadaists discovered the metaphysical paintings of Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico, and a world of mannequins and jaunty automata blossomed in Berlin. The point was to do away with “expressionistic brightly colored wallpapers for the soul,” Grosz declared, replacing it with the “objectivity and clarity of engineering drawing.” Inspired by Chirico, Dadaists and other artists populated their works with enigmatic objects (like the outsized rubber glove suspended from a wall in Chirico’s Song of Love) and reduced the human form to the anonymous figure of the artist’s dummy. This movement spread throughout Europe, ranging from Carlo Carrà in Italy to René Magritte in Belgium and Balthus in France, but German artists seemed acutely receptive in the postwar turmoil—especially Max Ernst during Dada’s brief heyday in Cologne. Ernst, a combat veteran, emerged from the war determined to throw caution to the winds in his pursuit of art, expressing it in unsanctioned or unconventional ways. He was wary of Berlin Dada’s political aims, but shared the enthusiasm for Chirico. The metaphysical anonymity of Chirico’s work proved readily agreeable to the Berliners, who repudiated anything that smacked of self-expression in art.

As Dada took on new forms in Berlin, the man who had brought it there in the first place struggled to keep pace. Despite his medical studies, though, Huelsenbeck found time to write numerous expositions of the Dada movement. It became something of an addiction as the decades went on, his collected ruminations adding up to more than six hundred pages. Between 1918 and 1920, he published eight articles on Dada and three books, as well as preparing a grand compilation called Dadaco he’d started planning as soon as he returned to Berlin in 1917. It was never published, but surviving multicolor proof sheets have graced the pages of books about Dada ever since, most famously that of Hugo Ball as the magic bishop.

Huelsenbeck lacked the sense of humor other Dadaists possessed; he brought to Dada a diagnostic outlook befitting a physician. He could even sound pedantic, itemizing the characteristics of Dada like spots on a toad: “One cannot understand Dada; one must experience it. Dada is immediate and obvious. If you’re alive, you are a Dadaist. Dada is the neutral point between content and form, male and female, matter and spirit.” This is from his introduction to Dada Almanac (1920), which opens with an attempt at the sort of conundrum Tzara specialized in: “One has to be enough of a Dadaist to be able to adopt a Dadaist stance toward one’s own Dadaism.” In this version, Dada sounds uncomfortably close to irony, but even Huelsenbeck would have known there was nothing ironic in the relentless zeal Dadaists applied to their activities. At other points, Huelsenbeck could make Dada sound like a healthy, robust outlook more readily associated with Americans: “Dada is the scream of brakes and the bellowing of the brokers at the Chicago Stock Exchange.” When he declares Dada to be “the international expression of our times,” you can faintly feel the tip of the whip he’s cracking in the face of Germans, for whom “international” was suspect, as it is for many Americans today.

From the first Dada evening in April 1918 through the end of 1919, there were a dozen public presentations in Berlin, as well as numerous impromptu actions along the way. Grosz would dress up as death, wearing an outsized skull, and, while smoking a cigarette and twirling a cane, stroll up and down Berlin’s fashionable Kurfürstendamm. Its commercialism revolted the artist: “Something like a public lavatory atmosphere, you understand, as well as a smell of very rotten teeth.” For a politically shrewd April Fool’s prank in 1918, Hausmann and Baader notified the authorities of the Berlin suburb Nikolassee that they were dispatching forces to establish a Dada republic there. The alarmed community mobilized its militia in response, two thousand strong, warily awaiting the onslaught of Dada hordes.

Dada seemed exceptionally suited to this time of extreme political volatility. A short-lived Soviet Republic was established in Munich in April, and more than a thousand died in the streets of Berlin in March. While those who attended its soirées might think of Dada as an artistic venture, for most the name circulated in the newspapers as a vaguely revolutionary threat, even a plausible political organization. In any case, programmed Dada evenings were chock-full of unmitigated aggression. Insulting the audience was de rigueur (“you’re not going to hand out real art to those dumbbells, are you?”). The Dadaists were out to pick fights, with bared fists. But they also put on skits.

Ben Hecht, the American correspondent who had introduced Dada to the readers of Chicago’s Daily News, continued to document some of its activities. It’s hard not to imagine the punchy dialogue of Hecht’s film His Girl Friday transmitting some of the Dada spirit, with its mile-a-minute wit, ferocious verbal pace, and political sympathy for the underdog. Of course, Hollywood could never condone the open taunts and bull-baiting tactics of Grosz or Hausmann.

Grosz liked hanging out with Hecht because he was that rare specimen, a real American. Still, Hecht didn’t recognize his new German friend when he stepped out onstage in blackface, wearing a frock coat and straw hat and dancing a jig. Grosz was master of ceremonies for “Pan-Germanic Poetry Contest,” in which a dozen scruffy contestants shuffled onstage. When he fired a starting pistol, all recited their poems simultaneously with histrionic gestures. At the concluding shot, he declared the contest a draw. “Recital for the Eye of Modern Music” was another venture, advertised in advance with a proclamation designed to get the goat of any good German: “Beethoven, Bach Are Dead—but Music Marches On.” Three damsels in tights came onstage, each placing a canvas on an easel, each canvas bearing a single musical note. Hecht reports the military brass in the crowd grew so agitated shots were fired, followed by demands for the arrest of the Dada hooligans who, in the meantime, had “melted into the spring night.” (This sounds like a fanciful report; the Dadaists themselves mention plenty of fisticuffs in their memories of such occasions, but no gunshots.)

Whether or not they led to violence, Dada performances provided a steady diet of antics. Grosz might pantomime a boxing match with a phantom adversary, or go through the motions of painting an imaginary picture. Sometimes, when the audience grew restless, the performers would line up, backs to the spectators, coolly remove their jackets and fold them up, light cigarettes, and stand, smoking and listening to the growing unrest behind them.

On the same evening he had interviewed Baader, the Oberdada, for “Stands on His Head to Conduct Meeting,” Hecht had witnessed the famous race between a woman operating a sewing machine and another, a typewriter—a send-up of Taylorist efficiency standards in the workplace. In this as in the other skits he reports, Hecht adds, “no applause.” In fact, the Dadaists would’ve been horrified by polite clapping. They sought catcalls, insults, and groans of dismay and welcomed even the flight of patrons from the venue. All the while, they insisted that the real nonsense was not theirs, but posing as political authority in the fraught world of German politics. That same night, Baader urged Hecht to consider “what compelling examples of sanity were our two friends who participated in the race between the sewing machine and the typewriter,” pointedly comparing the machines with the most prominent political figures of the moment: Friedrich Ebert of the Social Democratic Party and first president of the new German republic, and Philipp Scheidemann, provisional president and chancellor of the republic.

These occasions were undertaken in the spirit of a free-for-all. One reporter captured the mood: “The ‘artists’ appear with rolled up sleeves among the furious audience, screaming, threatening, egging on, sneering. They have had the success they wanted: they want turmoil; they want nothing but derision, dissolution, smashing up.” Because the Dadaists had no consensus among themselves as to what Dada was or what to do with it, they came onstage seething with rivalry and contention. “There’s no cooperative planning, no talk of companionship, at most each of us has the same right to raid the till,” Hausmann reported to Tzara in Zurich. They turned their mutual antagonisms on the audience like a fire hose. “Since we usually did a bit of drinking beforehand, we were always belligerent,” Grosz recalled. “The battles that started behind the scenes were merely continued in public, that was all.” All this was a far cry from the festivities of Cabaret Voltaire, where even the contrite Swiss were invited to read their sentimental poems onstage. Any discomfort the performers experienced at the cabaret came mainly from the manic pace of producing shows nightly. Berlin Dada performances were in galleries and concert halls, at a price point where the audience consisted of the bourgeoisie: those “respectable folks and coupon cutters” ruled by “the spirit of constant profit,” not really people at all but “libretto machines with an exchangeable moral disk.” The audience was a despised but handy target for these aspiring Communists and hectoring Dada impresarios.

Expert though he was at riling an audience, Raoul Hausmann embarked on a creative venture of his own, one that was more in the tradition of Cabaret Voltaire than Club Dada. His forte was sound poetry, which he likely heard about from Huelsenbeck’s account of wordless poems in Zurich. His exploration of “optophonetics,” as he called it, persisted beyond Dada. Hausmann had no interest in the singsong sonorities favored by Ball or the faux Africanisms of Tzara. He wanted to reach a primal place, where language had yet to evolve and the human animal vocalized without words. He pioneered a method of making sound effects by enunciating each letter, vocalizing type samples from a print shop or random letters strung together. These resources were the launchpad for producing all manner of sounds from what he called the “chaotic oral cavity.”

In this as in all his creative outlets, Hausmann’s approach reflects the influence of his friend Salomo Friedländer who, under the nom de plume Mynona (anonymous [anonym in French] spelled backward), published his philosophical treatise Creative Indifference, extolling the indifferent precondition of being. It’s the culture that conditions us to make distinctions like that between good and evil, whereas, Mynona postulates, our essential animal sapience is ready for anything. As Hausmann understood it, there was no reason for a poem with words to be inherently superior to a poem of growls and moans.

How could the saints of the Middle Ages compare, Hausmann wondered skeptically, with “the art of hairdressers, tailor’s dummies, and the pictures in fashion magazines”—anything that could inspire and nourish a new approach to life. “We must realize that our customary way of living, with its numb and lifeless impressions, encases us in clichés of reality created by habit and thoughtlessness.” Conditioned, conventional perceptions were an impediment to apprehending the new art. Yet “trains, airplanes, photography, and X-rays have pragmatically enhanced visual consciousness today with such powers of discrimination that, through the mechanical enrichment of natural potential, we have been liberated for a new optical cognition and the expansion of visual knowledge in a creative mode of life.”

While Hausmann was exploring the frontiers of modern art, and imagined himself adhering to the freethinking standards of his bohemian set, he was conducting a relationship with a fellow artist who was no less revolutionary in her outlook. Hausmann’s affair with Hannah Höch lasted the duration of Dada in Berlin. In that strident and aggressive milieu, Höch was tolerated by the others only because she was Hausmann’s girlfriend. Yet as Heartfield and Grosz bickered with Hausmann over who pioneered photomontage, they were oblivious to the fact that Höch trumped them all. Would they be chagrined to learn that a century later she would be widely regarded as one of the great twentieth-century artists, master of the technique over which they squabbled? At least Hausmann acknowledged her participation.

When they first got wind of Dada, Hausmann had prompted Höch with the idea that this was just the ticket for the two of them, something they could work on together. But it was a panacea, for their relationship was rocky from the start. Hausmann was married and even had a daughter (born in 1907 when he was just twenty). Not that Höch knew that when their relationship started; after their first sexual encounter on July 3, 1915, Hausmann wrote several poems commemorating them as “husband and wife in touch with the clearest understanding and the purest chastity”—indulging in bourgeois platitudes Dada reviled. The sacred occasion had been out at Wannsee, a popular resort west of Berlin, after they’d read Whitman together—the American bard being the great literary aphrodisiac for educated Europeans at the time. Yet Höch intuited something was off and a month later reproached Hausmann after he confessed his family secret. “Right from the beginning,” she said, “I sensed there was some sort of wall between us.”

And so the shuttlecock game between Höch and Hausmann commenced, persisting from 1915 to 1921. It was a classic farrago. Neither could imagine life without the other. Höch hated the fact of Hausmann’s marriage, and Hausmann resented the abiding bond Höch had with her family. The couple’s relationship could be abusive, judging from Höch’s references to Hausmann’s brutality. There were abortions in 1916 and 1918, driving them further apart. But other forces drew them together. For Hausmann it was the fertilizing boost of a soul mate. At heart he was lonely, alienated, his creative imagination fired not by a muse in the traditional sense but by real collaboration. In an early letter to Höch he lamented, “Which of my friends does not hate me?” Launched into the adventure of their new cut-and-paste practices, Hausmann clearly found in Höch a source of inspiration, not only because she was a genuine artist, but because she raised the level of his own game.

Hausmann did his best to have his cake and eat it, too. After his marriage was out in the open, he wanted Höch and his wife, Elfriede, to become friends. They did eventually meet, and in the ensuing row, Elfriede ended up siding with Höch. In the end, Hausmann left his wife in May 1918, though it wasn’t until 1920 that Höch consented to share an apartment with him, and even then their cohabitation was interrupted by the “flights” Höch took regularly from their relationship, often for months at a time.

The oldest of five children, Höch was artistically inclined from childhood, though for family reasons kept from formal instruction until she was twenty-three, when she entered the School of Applied Arts in Berlin. She was on a field trip with other students to Cologne when the war broke out, after which she worked for the Red Cross before returning to school, this time at the School of the Royal Museum of Applied Arts, where one of her fellow students was George Grosz. In 1916 she started working for Ullstein publishers, a position she held for a decade. This provided her with a steady supply of periodicals like BIZ (Berlin Illustrated News) from which she zealously snipped a cache of images for collages.

While Höch was one of the pioneers of the Dada art of photomontage, her official alliance with Dada was through Hausmann and her involvement was minimal: the Dadaists acknowledged female emancipation but did not welcome women in their ranks. In April 1919 she played pot lids and a toy rattle in Jefim Golyscheff’s antisymphony, and at the end of the year she participated in a “simultaneous poem” by Huelsenbeck.

Her most notable contribution to Dada was the collection of photomontages she exhibited in the First International Dada Fair, June–August 1920—and that was only because Hausmann insisted on it. The other organizers, Grosz and Heartfield, resisted, but Hausmann threatened to withdraw his own works if hers weren’t included. In this regard, at least, he seems to have been capable of being a supportive mate.

The First International Dada Fair turned out to be the only one of its kind. Though held in Otto Burchard’s art gallery, it was not billed as an exhibition but as a “Dada-Messe” (Dada fair), like a trade fair, befitting artists who called themselves mechanics. It was a stretch to call it international, since most of the nearly two hundred works on display were by Germans, mainly Berliners. Ben Hecht and Francis Picabia were token foreigners, with a Dada supplement by way of Max Ernst (Cologne) and Hans Arp (Zurich) to spice the stew. Apart from an ad for an athlete as doorman (read: bouncer), the occasion was devoid of that performance dimension for which Dada had become notorious in Berlin.

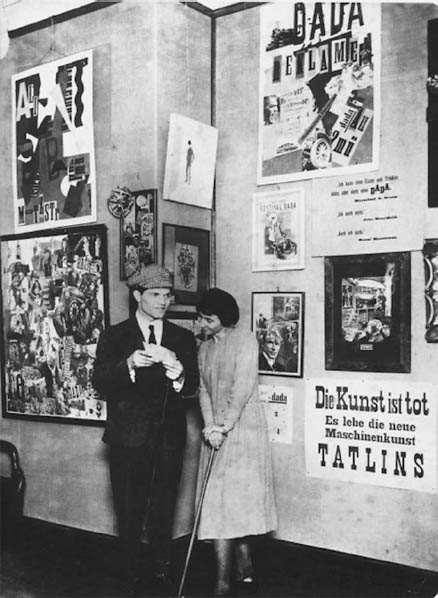

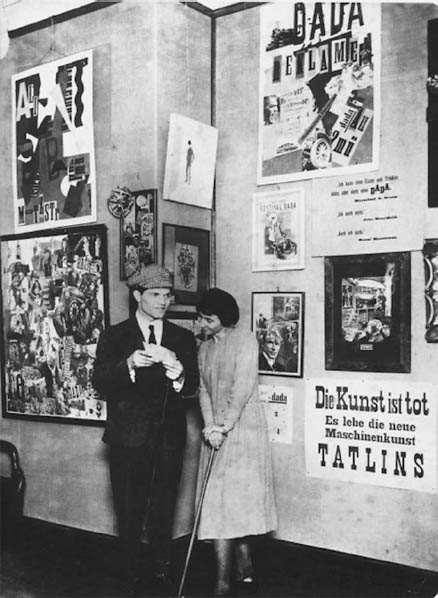

The Dada fair was relatively staid, judging from photos of what’s likely a preview, since the only people on view were Dadaists and a few of their friends, including architect and future Bauhaus director Mies van der Rohe. In the photos, they are dressed for an occasion, though the occasion might as well be an embassy affair, judging from their attire. For an exhibit plastered with slogans throughout, like “No more Philistine Spirituality” (though soul-mongering better expresses the attitude) and “Dada stands on the side of the revolutionary proletariat,” the artists in the photos look far removed from the working class.

But if the atmosphere in the photograph was composed, the artwork on display was anything but. Though an exhibition is not a performance in the conventional sense, here in Burchard’s gallery the walls were teeming with animation. The catalogue listed 174 works, but references from visitors and journalists make it clear there were quite a few more, all jammed into two rooms. Framed oil paintings jostled with unframed posters, collages on easels, overlapping prints on the walls, items hanging literally by a string if not a thread—all designed to make the eyes spin like propellers on a plane doing the loop de loop. To top it off, in the smaller room, Baader’s The Great Plasto-Dio-Dada-Drama: Germany’s Greatness and Demise or The Fantastic Life of the Oberdada was a veritable gusher of urban refuse.

At first glance a mangy heap, on closer inspection Baader’s collection of objects was a meticulous construction arranged by the architect of funerary monuments. It consisted largely of Dada publications, intact and cut up, mounted on a pyramid festooned with various objects, including a life-size, mustachioed mannequin, and topped by a mousetrap. A brochure elaborated on the structure of the heap, which consisted of “5 stories, 3 parks, 1 tunnel, 2 elevators and 1 cylindrical top. The ground level or floor, representing the fate determined before birth, has no further relevance. First floor: The Preparation of the Superdada. Second floor: The Metaphysical Exam. Third floor: The Initiation. Fourth floor: The World War. Fifth floor: World Revolution. Penthouse: The cylinder spirals into the heavens and proclaims the resurrection of Germany by way of schoolmaster Hagendorf’s lectern. Eternally.” Dada scholar Hanne Bergius calls this the “architecture of the imponderable”—a phrase even more apt considering Baader’s 1906 design for a Cosmic Temple Pyramid, a colossal structure meant to house universities (plural), libraries, museums, sports arenas, parks and gardens, pilgrimage sites, and even “woods and fields and mountains and meadows and brooks and lakes and rivers and the ocean.” Nothing less, Baader admitted, than a new Tower of Babel. At least The Great Plasto-Dio-Dada-Drama visibly replicated the babble, with its profusion of Dada publications from preceding years.

The sweetest photo of Höch and Hausmann together is at the opening of the fair. They look almost like teenagers on a first date. He’s wearing a plaid sports cap, shyly holding a piece of paper that she leans over slightly to see. They stand before a wall of pictures and slogans. One photomontage blurts out “Dada Advertising”; another reads “Art is dead. What’s alive is the new machine art of Tatlin,” a nod to the Russian artist who had sworn off easel painting and in the wake of the Russian Revolution dedicated himself to making his Monument to the Third International, one of the most iconic art objects of the twentieth century. Not that the Dadaists were familiar with what Tatlin was up to—they’d just heard about the new turn (soon called Constructivism) under way in the USSR from exiles swarming into Berlin.

Raoul Hausmann and Hannah Höch at the International Dada Fair, Berlin, 1920.

Photo by Robert Sennecke.

Another photo on the wall behind Hausmann and Höch shows a man dressed in a black head-to-toe bodysuit, standing in profile and slightly stooped like he’s about to make a jerky move. With a bowler tilted down almost over his eyes, something about his thin angular face makes him a ringer for Fred Astaire. The photo appeared in Der Dada 3 as part of a sequence illustrating the Dada-Trott, a variation on the ubiquitous foxtrot, only this one looks like the 1940s comic superhero Plastic Man, squeezed out of a tube and set convulsively in motion on an unsuspecting world.

The Dada fair was a big recycling bin. The organizers gathered together works created in various media and deployed them under the banner of Dada. They called the exhibited works Dada products (Erzeugnisse), like commercial goods. The variety prompted one journalist to characterize the show as “an anatomical museum where you can see dissections, not only arm and leg, but head and heart.” In fact, the theme of human vivisection was front and center in paintings like Forty-Five Percent Able-Bodied by Otto Dix, depicting the war cripples who flooded the streets of Berlin in 1918 and remained all too visible. (When the Nazis included this canvas in their “degenerate art” exhibition in 1937, they branded it a “Painted Sabotage Against the Armed Forces.” Then they exterminated the painting itself.) Dismembering the human form was a mainstay of photomontage, in which heads and bodies were cleverly combined with machine parts and industrial products to make hybrid concoctions tacitly announcing the bankruptcy of humanist self-regard.

For some indignant visitors, the fair was a venue that sullied the human form and, worse, insulted the beleaguered military. The most offensive item hung from the ceiling: a dummy dressed in an officer’s uniform with a pig snout for a face, titled Prussian Archangel. His belt bore an inscription from a Lutheran hymn: “From High Heaven I Descend,” and a placard hanging down from the mannequin (reprinted in the catalogue) advised: “To perfectly grasp this artwork, drill twelve hours daily with loaded backpack and combat gear in Tempelhof Field”—a military training ground in Berlin.

This pig-officer was too much for some pious Germans to bear. Prosecutions were brought against the “perpetrators.” In the end, Rudolf Schlichter (who with Heartfield had fabricated the archangel) was acquitted, as was gallery owner Burchard. Grosz was fined 300 marks for the portfolio God with Us sold at the fair, and Wieland Herzfelde as publisher fined twice that amount. The plates and remaining copies were seized and destroyed. At the trial, Baader pointed out that Germans might be better respected in the world if they could laugh at themselves. The New York Times headline summed it up: “Dadaists on Trial as Army Defamers Charged in Berlin with Insulting the Reichswehr in ‘Art’ Exhibition Gave Officer Pig’s Face Chief of Cult Complains that Germans Lack a Sense of Humor.” The alarmist rhetoric of the prosecution proved a self-caricature of official pompousness.

Certainly the year before, when revolution was in the air and combat in the streets, such an exhibition would have seemed an unmistakable act of political agitation, but in the tentative stabilization of the Weimar Republic, it smacked of hoax, not threat. The humorous dimension had in fact been writ large in the press notice written by Hausmann announcing the fair. Composed as a spoof of the pompous official pronouncements to which Germans were accustomed, readers of the June 26 edition of Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger were informed: “All Dadaists in the world have delegated their psycho-technical elasticity to the Berlin agents of immortal Dada. Everybody should see the wonder of this psycho-metalogy. Dada overtrumps every occultism.” In a dizzying drumroll of words, indulging in the German propensity for compounding nouns with prefixes and suffixes, Hausmann cut loose: “Dada is the clairvoyance of the insight into the viewpoint of any opinion [die Hellsicht der Einsicht in die Aussicht jeder Ansicht] about politics and business, art, medicine, sexuality, erotics, perversion, and anaesthetics.”

Hausmann’s gift for turning the tables on the opposition came to the fore in the exhibition catalogue, printed three weeks after the fair opened. In it, he incorporated the bulk of a negative review: “What you see in this exhibition is of such a low standard you have to wonder how a gallery could get up the courage to show this stuff.” Clearly, anyone lured to the fair by such an appraisal could hardly cry wolf when confronted with the Prussian archangel or anything else on display, including a tailor’s dummy with a lightbulb for a head, revolver in place of one arm and a doorbell for the other, military decorations pinned to the chest, a prosthetic leg, and a pair of false teeth in the crotch. The title was self-parodying: The Philistine Heartfield Run Amok.

Official concerns for the moral well-being of the republic notwithstanding, the Dada fair posed no real threat to German politics or culture. In fact, it may have been the least public forum organized by the Dadaists in Berlin. Midway through its two-month run, only 310 admission tickets had been sold. By contrast, the First Exhibition of Russian Art at the Van Diemen Gallery in Berlin in 1923 drew 15,000 visitors; the 0.10 exhibit of Futurism in St. Petersburg in 1915 attracted 6,000 in a single month; the legendary 1913 Armory Show drew 88,000 in New York and 188,000 when it went to Chicago; and the Futurist exhibit of 1912 garnered some 40,000 viewers as it toured the Continent after its Paris debut. Manet and the Post-Impressionists in London was seen by 25,000, among them Virginia Woolf, emboldened by the experience to declare 1910 the year human nature changed.

None of these attendance figures, however impressive, would be able to rival Degenerate Art, the exhibition mounted by the Nazis in Munich in 1937, with over two million, with another million as it went on the road throughout Germany. Certainly far more people saw the work of the Berlin Dadaists vilified there than celebrated at the First International Dada Fair in 1920. Yet there were strange parallels between the two events. The incendiary manner of displaying the art was ironically indebted to Dada, a point not lost on Höch, who attended this infamous exhibit. She was moved to note the almost reverential looks with which the silently attentive crowds viewed this massive cross-section of all that had been most inventive and vigorous in modern art.

The pieces on display at the 1920 Dada fair were perhaps more inventive and energetic than any works of modern art theretofore. As soon as attendees entered, they confronted three huge posters, on each of which was a large photo of one of the organizers accompanied by a slogan. “Down with art,” read the caption over the image of John Heartfield, mouth open with hands framing his shout. Hausmann appears on the verge of growling, under the slogan “Finally open up your mind!” Grosz, in profile, looks like a Roman dignitary on a coin, framed by two proclamations: “Dada is the deliberate subversion of bourgeois ideology” and “Dada is on the side of the revolutionary proletariat.” Below these images was stationed a young woman at a table selling copies of Malik publications. Nearby were Höch’s two Dada dolls and, proudly displayed above, the colorful issue of Neue Jugend with the Flatiron Building.

In one way or another, visitors to the fair were exposed to most of the Dada publications, some intact, others cut up in the numerous collages on display. There were a couple of portraits Hausmann had made of friends consisting entirely of snipped publications, and in keeping with the posters at the entrance, the art of self-portraiture was abundant. In Hausmann’s Self-Portrait of the Dadasoph a pressure gauge and other mechanical parts stand in for the head, the torso consisting of a colored anatomical illustration of a human lung. Grosz’s watercolor The Mechanic John Heartfield, after Franz Jung’s Attempt to Put Him Back on His Feet depicts the artist as a military thug. Grosz portrayed himself as a mechanical compilation along with an unflattering likeness of his new wife in ‘Daum’ marries her pedantic automaton ‘George’ in May 1920, John Heartfield is very glad of it. The original title was in English. Grosz affectionately called his wife, Eve, Maud—the spelling reversed here. Grosz and Heartfield collaborated on a portrait of Huelsenbeck, otherwise missing from the exhibit except for a copy of Fantastic Prayers, included more for Grosz’s illustrations than for the poems. In a Grosz photomontage, Huelsenbeck’s nattily dressed figure floats in a circle framed by a triangle (a variation on Leonardo’s Vitruvian man); lacking feet and head, the body is extended by a printed sputter of letters: “dad a dada dadadadadada.”

Portraiture extended to other works as well, as in a touched-up death mask of Beethoven, used for the cover of Dada Almanac, by Dada-Oz (Otto Schmalhausen). Also on view was an issue of Picabia’s magazine 391 with Marcel Duchamp’s mustachioed Mona Lisa. In Disdain for a Masterpiece by Botticelli, Grosz effaced the famous Primavera of the Italian master with an aggressive X. Belligerence abounded, but lighter touches could be found as well. Baader’s Honorary Portrait of Charlie Chaplin made no effort to depict the endearing film star; instead, the “portrait” was a dense patchwork of cutouts of newspaper headlines and letters glued together like a bird’s nest. In Höch’s Da Dandy, the silhouette of a man swarms with faces of models clipped from fashion magazines.

Höch could be as wittily aggressive as the guys. Dada Panorama made use of an infamous photograph of President Ebert and army minister Noske (notorious for his brutality during the Spartacist uprising) bathing at Wannsee, both of them dumpy and unfit. Höch’s triumph, and the highlight of the show, was the immense photomontage, cinematically titled Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Epoch of Weimar Beer-Belly Culture in Germany. It’s tempting to say it has a cast of thousands. There are crowd scenes, including dozens of recognizable people ranging from Karl Marx and Albert Einstein to most of the Dadaists themselves. Höch’s teeming vision merits all the attention it’s gotten over the years, making it possibly the most celebrated single work that was on view at the Dada fair.

Cover of the second edition of Fantastic Prayers by Richard Huelsenbeck, illustrated by George Grosz, 1920.

Art copyright © Estate of George Grosz, licensed by VAGA, New York; University of Iowa Libraries, International Dada Archive.

One of the most iconic productions of Berlin Dada, however, was not at the fair. This was Hausmann’s Mechanical Head: The Spirit of Our Times, which he said was meant “to indicate that human consciousness was nothing but negligible accessories, pasted on the surface, nothing but a hairdresser’s mannequin with a pretty wig.” To make it, Hausmann had sanded a wooden bust down to a fine polish, mounted a tin cup on top (a hunting accessory from Höch’s father), and run a tape measure down from the cup to the eyebrows. Also on the forehead was a piece of cardboard with the number 22, “because, obviously, the spirit of our time has but a numerical signification.” In place of the right ear, Hausmann affixed a jewel box, hanging open so you can see a pipe stem attached to a typographic cylinder. On the left ear, part of the mechanism of a tripod protrudes, onto which is mounted a ruler that rises up like an antenna. Finally, he glued a wallet on the back (looking somewhat like a mullet).

In Mechanical Head, the “new man”—heralded by Huelsenbeck and fast becoming a slogan of the German avant-garde—has been trumped by an automaton. Hausmann dated this assemblage from 1919, but it’s inconceivable he would have withheld it from the fair, suggesting he made it closer to the date of its first public appearance in 1921 at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition. The Dada fair did include a few of his collages in which mechanical parts were incorporated into human bodies: Self-Portrait of the Dadasoph and Tatlin at Home, as well as a few “grotesques”—sketches of robotic creatures from his 1920 book Hurra, Hurra, Hurra! Most of the Chirico-inspired zombies—like Hausmann’s Engineers, Kutschenbauch Composes, and, of course, the Mechanical Head, along with Schlichter’s Dada Roof Atelier—clearly postdated the fair.

Grosz, too, was swept up in the enthusiasm for Chirico, and at the end of the year he summed up his position in “On My New Paintings,” an article published in 1921 in Das Kunstblatt: “Man is no longer shown as an individual, with psychological subtleties, but as a collectivistic, almost mechanistic concept. The fate of the individual no longer counts.” In works like Republican Automatons and The New Man he abandoned his skittery graffiti lines in favor of humanoid templates, artists’ dummies on which details might be subsequently applied, if at all. “A time will come when the artist will no longer be a soggy bohemian anarchist,” he hoped, “but a bright, healthy worker within the collective community.” Such visions would soon be dispelled, for various reasons, but it was the last gasp of solidarity that had bound together a few individuals in Berlin as they clung to the juggernaut of Dada.

After the fair closed at the end of August 1920, Dada in Berlin dissipated as quickly as a blown dandelion. Whatever it had been was a mystery wrapped in an enigma, shrouded by provocations and taunts. Lest anybody think of rekindling the spark, in 1921 Hausmann announced the suspension of Dada activities until humankind had evolved enough to embrace its spiritual elasticity.

Not long after the fair ended, a final publication appeared, Dada Almanac edited by Richard Huelsenbeck. Like The Blue Rider Almanac in 1912, it was the only one of its kind. Dada Almanac remains the only comprehensive portfolio assembled by a Dadaist during its heyday, although surviving proof sheets of the aborted Dadaco, on which Huelsenbeck had worked since returning to the city in 1917, suggest it would have been more colorful, flamboyant, and lavishly produced.

Published in a compact format with 160 pages and eight photographs, Dada Almanac drew the lion’s share of its contents from the Berlin scene but also reprinted items from several other countries to promote Dada’s international character. Huelsenbeck’s introduction is a fairly straightforward exposition of the Dadaist as someone “free to adopt any mask; he can represent any ‘art movement’ since he belongs to no movement.” Elsewhere in the volume Huelsenbeck included his introductory remarks about Dada from the Neumann Gallery reading in January 1918 and his manifesto from the first official Dada evening three months later.

Following Dada Almanac’s introduction was Tzara’s typographically lively chronology of Dada in Zurich, detailing events through 1919. He concluded with the claim that “8,590 articles on dada have appeared in the newspapers” from fifty-six cities around the world, listed in no particular order. Because Tzara was an indefatigable archivist of all things Dada, it’s plausible that press coverage actually penetrated these locales, but the thousandfold total sounds like a Dada dream too good to be true. Huelsenbeck included ten pages of excerpts from this cache in the almanac, not all accolades. Some were characteristically obtuse, but several included sensible observations. It was noted that while visiting a Dada exhibition “you discover that it is possible to laugh again.” From another: “Dadaism is thus not an art movement: it is the confirmation of a feeling of independence.” Even a naysayer was moved to acknowledge, “In the fine art of advertising their genius should be admitted even by their enemies.”

Dada Almanac was liberally sprinkled with disinformation, like the “Dadaist aperçus” at the end of the volume. The subterfuge begins right after Tzara’s chronicle, when one Max Baumann (surely Huelsenbeck himself) lights into the Oberdada for five pages, accusing Baader of money grubbing, in his use of Dada to fund his private mania, and dubbing him “a Kurt Schwitters dressed up as a messiah, a dilettante’s mind in cosmic underpants.” Hanover artist Schwitters (subject of the next chapter) had been spurned by Huelsenbeck when he tried to join Club Dada. Huelsenbeck was so incensed by the success of Schwitters’ book Anna Blume—generally received as a Dada publication—that he made a point of repudiating it in his introduction to Dada Almanac. So in a single sentence “Max Baumann” dispatched Huelsenbeck’s two bugbears.

The biases of the almanac’s editor is further revealed in the absence of political writings, though this omission might be justified as the book was strictly literary. Dada was profiled in the almanac as an international literary movement, with poems largely from the Parisian scene, plus one by Arp and another by Walter Mehring that expressed the razor-sharp wit he was honing in Berlin cabarets (“Jews out, stomachs in”). Hausmann’s article comparing tendencies in art with national cuisines (“Expressionism,” he proposes, “could only have arisen in the land of dumplings”), along with elements of pastiche and satire throughout Dada Almanac, conveys the sense of Dada as apolitical and not all that serious. Mehring’s fanciful assertion that “the world is only a branch of Dada,” like Baader’s claim that the Great War was strictly a phantasm created by the press, reinforces this sense. Above all, and in spite of Huelsenbeck’s disdain for him, the almanac affirms a sentiment best expressed by none other than Baader: “Whatever dada is, none of the Dadaists knows, only the Oberdada, and he’s not telling.”