The handsome young Frenchman arriving in New York on the SS Rochambeau on June 15, 1915, was in every respect the opposite of immigrants from previous decades. While earlier immigrants had passed through Ellis Island ready to throw themselves into a new life of hard work, this young man could be described as indolent. Although he had abilities and accomplishments, there was something in his nature that resisted making a career of it—the it in question being art. He was an artist and, given his family background, maybe that was part of the problem. He had two older brothers whom he idolized, already established in their own careers as artists. What’s more, they’d gathered around them a group of like-minded colleagues defiantly committed to the new aesthetic associated with Cubism.

Young Marcel Duchamp attended these early Cubist meetings, marveling at the assurance with which his brothers Raymond Duchamp-Villon and Jacques Villon (both had changed their names when taking up art) pursued their goals. At a deeper level, Duchamp must have felt that one more artist from the family was a bit much (and this was even before his younger sister Suzanne joined the ranks). Whatever inclination he had to confront the revolving wheel of fashion and upstart causes was rapidly dissipating.

When the Great War broke out, Duchamp proved indifferent to the patriotic euphoria. And almost as a physical symptom of his ennui, he was deemed medically unfit for service. As war fever assumed a steady state in the months after the initial waves of mobilization, Duchamp found himself repeatedly chastised in the streets of Paris as a presumed slacker. After all, he was young, lean, and looked fit. By 1915, tired of dirty looks and with so many from his circle of artists called up for service, he decided to get away from it all and thought New York might be a good haven. As he insisted to a friend, he wasn’t going to New York, he was leaving Paris behind. That sort of scrupulous distinction would become a hallmark of his new life in America.

As he sailed into the harbor, unsettled by a heat so intense he thought there must be a fire nearby, Duchamp had no idea he was arriving in a city where he had already achieved celebrity status two years earlier. When he set foot on shore, then, he was gratified to find himself welcomed in style by his old American friend Walter Pach, who had arranged for Duchamp to stay with Walter and Louise Arensberg. He was whisked off straight from the dock to the apartment of the Arensbergs, wealthy art patrons who had moved to New York from Boston shortly before he arrived. Soon after his arrival, their apartment would become the center of a growing international avant-garde, with the newly arrived Frenchman as centerpiece.

From our vantage of instantaneous and ubiquitous messaging, it’s hard to grasp a time when a seismic cultural event in the United States wouldn’t even register as a back-page item in the European press. But that’s how it was when the legendary 1913 Armory Show ruffled the feathers (plundered the coop might be more like it) of American culture.

Headlining the bewildered response as the show went from New York to Boston and Chicago was Nude Descending a Staircase by an obscure French artist named Duchamp, drawing more than its share of lampoons in the press. “Food Descending a Staircase,” “The Rude Descending a Staircase (Rush Hour at the Subway),” “Huntsman Descending a Staircase With His Dog,” “Aviator Descending from an Airplane,” and “Portrait of a Lady Going Up Stairs Not Down Stairs” were variant spoofs on Duchamp’s theme, though a characterization of it as an explosion in a shingle factory proved most durable (spawning its own variant: “Sunrise in a Lumber Yard”). A Life magazine illustrator adapted the principle to baseball in “A Futurist Home Run.” Nude Descending a Staircase even influenced L. Frank Baum to create the character Woozy in The Patchwork Girl of Oz (1913). Her motto: “I always keep my word, for I pride myself on being square.” The painting’s repute was extended by a postcard reproduction sold by the exhibitors.

The Nude, along with three more of Duchamp’s paintings, had been chosen by the organizers as they scurried about Europe, scooping up whatever was available for their planned exhibition. Americans attending the Armory Show had no idea what they were in for, and the same could be said of the organizers. When Walt Kuhn caught the Sonderbund exhibition in Cologne on its last day on 1912 (with 125 works by Van Gogh, 25 by Gauguin, 26 by Cézanne, and 16 by Picasso), it was his first exposure to the radical direction European painting had taken in recent years. His frantic visits to Munich, Berlin, The Hague, and finally Paris in the next few weeks revealed how widespread these tendencies were. If the organizers were really going to present modern art to modern America, these Expressionist, Futurist, Fauvist, and Cubist pictures had to be included. The Armory Show was intended as a showcase for American artists, but their work was overshadowed by the Europeans, a plague of modernism every bit as potent as Freud’s and far more immediate in its impact.

The Armory Show was massive, with over a thousand works by three hundred artists jammed into eighteen galleries partitioned by burlap in the cavernous 69th Infantry Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue in midtown Manhattan, February–March 1913. Given the glut, it’s not surprising that word-of-mouth and press notices excited visitors’ anticipation of the “chamber of horrors” awaiting them at the end—ample fodder for cartoonists who zestily assimilated the pictorial innovations of these “nuttists,” “dope-ists,” “topsy-turvists,” and “toodle-doodle-ists” satirized in New York American. The throng of visitors proved typically American in their appetite for shock, and overflow crowds continued when the exhibit moved to Chicago, where the American contributions were much reduced. By the time it ended up in Boston, the Americans were eliminated altogether, ostensibly owing to the smaller exhibition space but in effect verifying that it was the modernist onslaught from Europe that merited attention. In the multitude of cartoons, the work of the Europeans—Duchamp, Picabia, Matisse, Brancusi, and others—invariably drew ridicule.

A mock counterexhibition was held under the delectably named Academy of Misapplied Arts (sponsored by Lighthouse for the Blind), in which a Picabia Neurasthenic Transformer was on view. The schemer behind this was humorist Gelett Burgess, famous for his purple cow and for coining the word blurb. Burgess appended Picabia’s name to a device he’d been tinkering on, profiled in 1912 in The Bookman, where it was purportedly intended “for the elimination of thought in all forms” and prompting “nonsense in three dimensions.” (Although Picabia was not yet manifesting symptoms, on his 1915 sojourn in New York he did undergo treatment for neurasthenia.) In his faux dictionary, Burgess Unabridged, Burgess coined diabob as the term for “an object of amateur art” with the adjectival form diabobical meaning “ugly, while pretending to be beautiful.” In a dig at the Armory Show, Burgess writes:

And yet, these diabobs, perhaps

Are scarcely more outré

Than pictures made by Cubist chaps,

Or Futurists, today!

In hindsight, it’s easy to pity the poor saps of yesteryear who confidently leveled such stinging ridicule against works of art that would, in short order, revolutionize modern culture. Take Kenyon Cox, a now-forgotten artist who in 1913 was a widely cited figure of authority. Asked by a reporter from the New York Times to comment on the new art, Cox solemnly declared—on the basis of “a lifetime given to the study of art and criticism, in the belief that painting means something”—that Postimpressionism was merely “the deification of Whim” perpetrated by men who were either “victims of autosuggestion” or “charlatans fooling the public.” Cox, like other pundits who sought to enlighten the public, thought Henri Matisse was the archcharlatan. He claimed that for Matisse and the Cubists and Futurists (notwithstanding that the latter refused as a group to contribute to the Armory Show) plying their trade as artists was “no longer a matter of sincere fanaticism. These men have seized upon the modern engine of publicity and are making insanity pay.” Ironically, it was precisely by this engine of publicity that Cox’s views were circulated—in a pamphlet sold at the Armory Show’s Chicago venue, no less. The sponsoring organization, the Association of American Painters and Sculptors, issued various pamphlets and postcards to be sold on premises, and one called For and Against was prepared in the wake of the New York show. True to its title, it gives equal weight to both sides of the debate.

Cox’s position comes across as relatively tame next to that of Frank Jewett Mather Jr., whose “Old and New Art” was reprinted from The Nation. Mather shared the general alarm over the “irresponsible nightmares of Matisse” and found new art “essentially epileptic.” Taking in the exhibit, he suggested, resembled “one’s feeling on first visiting a lunatic asylum,” acknowledging that its “inmates might well seem more vivid and fascinating than the everyday companions of home and office,” just as “a vitriol-throwing suffragette [is] more exciting than a lady.” Confronting the work of Picasso, Picabia, and Duchamp, Mather equivocated as to whether it was “a clever hoax or a negligible pedantry.”

One thing that all the commentators agreed upon, even the most vituperative, was that the organizers had done a real service in assembling such irrefutable evidence of the modern movement in art, presenting it in a spirit of neutrality in order to let the public decide for itself. And decide it did, generally along the lines spelled out by an anonymous reviewer for the Chicago Evening Post: “Everyman Jack of them had nailed his own flag to the masthead, issued to himself his own sailing orders and was out on the high seas, doing precisely as he pleased.” In the aisles of the Armory Show, the public discovered the aesthetic equivalent of the iconic American gunslinging outlaw and was equally fascinated. They might find it as alarming as did the reviewer for the Chicago Evening Post, but they were mesmerized by such artistic audacity.

Visitors who weathered the visual assault and didn’t dismiss the new art outright tended to take the experience as a lesson or a necessary medicine hard to swallow. “We are in an anaemic condition which requires strong medicine, and it will do us good to take it without kicks and wry faces,” wrote Harriet Monroe, editor of Poetry magazine. Hutchins Hapgood, Greenwich Village bohemian, told readers of the New York Globe, “It makes us live more abundantly.” That was certainly the experience of lawyer and art collector John Quinn: “When one leaves this exhibition one goes outside and sees the lights streaking up and down the tall buildings and watches their shadows, and feels that the pictures that one has seen inside after all have some relations to the life and color and rhythm and movement that one sees outside.” What Quinn found salutary was what the genteel public—with its belief that art was a hothouse flower far removed from the rough and tumble of the street—held most objectionable. A setting more ripe for the assault of Dada could not be imagined.

Piqued by the influx of modern art from Europe, the press thronged to greet one of the artistic buccaneers as he disembarked at the port of New York on January 20, 1913. The artist—a Frenchman, arriving two years before Duchamp—was featured on the front page of the New York Times on February 16, 1913, as “Picabia, Art Rebel” and hyperbolically identified as “the chief of those pirates of art.” But this was a courteous and solicitous buccaneer: “It is in America that I believe that the theories of The New Art will hold most tenaciously,” Picabia said. “I have come here to appeal to the American people to accept the New Movement in Art in the same spirit with which they have accepted political movements to which they at first have felt antagonistic, but which, in their firm love of liberty of expression in speech, in almost any field, they have always dealt with an open mind.” Speaking just a day after the Armory Show opened, which the public at large had yet to view, Picabia assured people they were bound to embrace the new art.

What Picabia soon discovered, as virtually all the European exiles in the coming war would reaffirm, was that the sheer force of modernity concentrated in the city of New York outstripped anything in the sphere of art. Amy Lowell, who considered herself a beacon of the advanced cause of Imagism, decided that “the most national things we have are skyscrapers, ice water, and the New Poetry.” Lowell had a sentimental attachment to poetry, but from the perspective of Picabia, a skyscraper like the Woolworth Building was a standing reprimand to artistic timidity; and soon Marcel Duchamp would come up with the zany notion of signing his name to the building (then the world’s tallest) and declaring it one of his “ready-made” artworks. But he couldn’t think of a fitting title, so the Woolworth Building never became the world’s largest ready-made.

Picabia was born into wealth and privilege and generally behaved with a presumption of immunity from social norms, however debonair his manners and tailored his wardrobe. A case in point is his second visit to New York when he was supposed to be carrying out a military mission in Cuba. Taking advantage of the ship’s itinerary, he disembarked at New York to rejoin his old friends and found an agreeable milieu awaiting him, from which he found it impossible to withdraw.

During the Armory Show, Picabia was instantly if warily lionized as a bona fide French artist willing and eager to put himself on the line for a cause, the cause of modern art. He struck up a fast friendship with Alfred Stieglitz, champion of photography as a legitimate art, editor of Camera Work, and proprietor of 291 Gallery, where he mounted an exhibition of Picabia’s works in the wake of the Armory Show. Picabia’s statement for the catalogue (reprinted in the “For and Against” pamphlet) isn’t particularly incendiary. He helpfully suggested that the public not seek any “photographic” material in his paintings, because he was working in the spirit of a “qualitative conception of reality” to which optical phenomena were subordinated. The result, he admitted, approached abstraction, a term then barely broached in art.

Francis Picabia, photographed by Man Ray, 1922.

Copyright © 2014 Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Picabia, along with Wassily Kandinsky and Czech painter František Kupka, were among the first to take the leap into abstraction, and for all three the operative analogy was with music, a theme Kandinsky had taken up the year before in his book Concerning the Spiritual in Art. One rejoinder to those who professed to see no nude in Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase was to ask, Where is the moon in the Moonlight Sonata? Even before he ventured down the rabbit hole of abstraction, critics had found in Picabia’s work a “musical emotion.” Charles Caffin, reviewing his contributions to the Armory Show, found him “emulating the musicians as he manipulates the notes of the octave, starts with a few forms, colored according to the key of the impression he wishes to create and combines and recombines these in a variety of relations until he has produced a harmonic composition.” Caffin was following a well-worn path identified in 1877 by English aesthete Walter Pater, when he observed that all the arts were aspiring to the condition of music.

In 1905 Kupka wrote to a friend, “I paint only the conception, the synthesis; if you like, the chords.” He was prone to signing his letters “color symphonist,” but it wasn’t until 1913 that his quest for visual music plunged through to abstraction. “I am still groping in the dark,” he wrote, “but I believe I can find something between sight and hearing and I can produce a fugue in colors.” By that point, Roger Fry was referring to Kandinsky’s work as “pure visual music.” “This new expression in painting is ‘the objectivity of a subjectivity,’” Picabia declared in his statement for 291 Gallery, adding: “We can make ourselves better understood by comparing it to music.”

Picabia drew on this comparison when interviewed by the New York press. He spoke of “a song of colors” to a reporter from World Magazine. “I simply equilibrize in color or shadow tones the sensations which those things give me. They are like the motifs of symphonic music.” He pressed the point a bit further in The New York American: “I improvise my painting just as a musician improvises his music.” Most of the newspaper profiles quoted Picabia at length as if he stepped off the boat chattering away in English, a language he never learned. The journalist for the New York Tribune didn’t quote Picabia but assimilated his lesson, reiterating the point that “just as music is only a matter of sounds, so painting is a matter of form and color.” And, adding the spice of analogy: “It was Bill Nye who, in one of his wittiest remarks, said that the funniest thing about classical music is that it is so much better than it sounds. In the same way the uninitiated may say of M. Picabia’s Post-Cubism that it ‘listens’ so much better than it looks.”

Picabia completed two large canvases in New York in 1913 and characterized them as “memories of America, evocations from there which, subtly opposed like musical harmonies, become representative of an idea, of a nostalgia, of a fugitive impression.” Picabia’s efforts to pictorialize music were augmented by his marriage to Gabrielle Buffet, a trained musician who had studied with such luminaries as French composers Gabriel Fauré and Vincent D’Indy and Italian composer Ferrucio Busoni. As the Tribune reporter noted, she brought to the cause of her husband’s career and modern art generally a “remarkably large” technical vocabulary in “exceptionally fluent English and German.”

The consistency of the reportage in 1913 suggests that Picabia was patient and accommodating when dealing with members of the press. Apart from the musical analogy, he routinely explained how photography, with its accurate recording of objects, had freed art from its old mimetic obligations. The art of the past belongs in the museums as a reference point; according to Picabia, such work is “for us what the alphabet is for a child.” To advance beyond mere spelling to the complexities of expression—grammar and syntax—is the goal. So the viewer should not search the surface of the painting looking for recognizable forms. “Did I paint the Flatiron Building or the Woolworth Building, when I painted my impressions of the fabulous skyscrapers of your great city?” he asked. “No, I gave you the rush of upward movement, the feeling of those who attempted to build the Tower of Babel.” Picabia was in pursuit of “the mental fact” or “emotive fact,” identified as precisely that which photography cannot reveal. “Creating a painting without a model of any kind: that is what I call art.”

Reporters were eager to learn how their city was affecting Picabia’s painting, and he encouraged their interest by pointing out they already inhabited a sort of Postimpressionist urban milieu. “You New Yorkers can readily understand me, just as you can those other painters who are my colleagues. Your New York is the Cubist, Futurist city; with its architecture, its life, its spirit, it expresses modern thought. You have skipped all the old schools and are Futurists in word, action and thought.” The New York Herald reported, under the racist headline, “Mr. Picabia Paints ‘Coon Songs,’” that Picabia had found inspiration in two “coon songs” he heard performed at a restaurant. The following day he produced two paintings called Negro Song. American artist Jo Davidson was asked, in the debased idiom of the day, “Do you think he shows us the coons?” Not at all, he replied, “he shows us a grand shuffle of deep purple and brown curved globs of color.”

When the Picabias departed after the Armory Show in April 1913, Stieglitz wrote a friend that they “were about the cleanest propositions I ever met in my whole career. They were one hundred percent purity. This fact added to their wonderful intelligence made both of them a constant source of pleasure.” They left a glow still luminous when Picabia returned in 1915, abandoning his military mission and hurling himself into a life of debauchery only someone with his means and temperament could command. The Stieglitz circle was naturally gratified to see him back in town. Because 291 Gallery was not so much a commercial enterprise as it was Stieglitz’s private auditorium, his associate Marius de Zayas was in the midst of establishing another gallery as a more commercial alternative, and the first exhibit at his Modern Gallery showcased Picasso, Braque, and Picabia.

Picabia was featured in a succinct profile in Vanity Fair that December, as a follow-up to its profile of Duchamp in September. “Marcel Duchamp has arrived in New York!” the unattributed author breathlessly reported, while the accompanying photo of the artist (in polka-dot bow tie) made him look a decade younger than his twenty-eight years. Picabia, by contrast, looks utterly relaxed for Stieglitz, gazing into the camera as if taking precisely thirty seconds out of his busy life; but instead of his dissipations, the text covers his self-serving lead, reporting that he may be called back into combat at any moment. (His closest bout with combat would come a few years later when the husband of a woman with whom he was having affair went after him with a pistol.) The article more accurately tracked the twists and turns of his art, from his salon background (“An Extremely Modernized Academician,” reads the subtitle), to the phase in which “I tried to make a painting that would live by its own resources, like music,” and the mechanomorphic concoctions he was then developing: “Picabia likes to make a picture of the interior of a motor-car and call it a portrait.” On October 24 he was quoted in the New York Tribune on this new turn. “Almost immediately upon coming to America,” he said, “it flashed on me that the genius of the modern world is in machinery, and that through machinery art ought to find a most vivid expression.”

With his proposal to the Tribune reporter that painting might profitably address the teeming new world of machines, so conspicuous in America, Picabia unwittingly embarked on a path that would directly impact Dada. In the meantime, though, his concerns and stimuli were strictly local, and increasingly absorbing, especially once Picabia was plunged into a vertiginous reunion with his old Paris friend, Duchamp.

A familiar notion of Duchamp as a grand wizard who purportedly abandoned art for chess was established as early as 1924, when he was depicted playing chess with Man Ray on a Parisian rooftop in René Clair’s film Entr’acte. But by the time he arrived in New York he already had a tenuous relation to art. Instead, he became fully immersed, as Dada itself was, in the unplanned and the unforeseeable, lighting matches to those moments as they came. There were plenty of moments, and plenty of matches.

And there was Picabia, a cultural arsonist if ever there was one. The two men shared a deep, unremitting, and resourceful nihilism. Where others might politely disagree by beginning a sentence with “Yes, but . . .,” Picabia’s rejoinder would be “No, because . . . . ” Duchamp was mesmerized: it must have seemed like looking in a mirror—and seeing another face. He credited the older artist with introducing him to a spectrum of new experiences in 1911–1912, at a time when Picabia was smoking opium every night—though Duchamp refrained. “A dangerous and enticing wind of sublime nihilism / pursued us with incredible exhilaration,” Picabia wrote in a poem called “Magic City,” which commemorates those “Years of genius” marked by “sterile passions” like opium, whiskey, and that new dance craze, the tango.

The bond between Picabia and Duchamp had been sealed before the war, during a long car trip with poet Guillaume Apollinaire (Picabia owned scores of cars during his lifetime). “Apollinaire often took part in these forays of demoralization, which were also forays of witticism and clownery,” Buffet-Picabia, Picabia’s wife, recounted. Visiting her family home in the Jura near the Swiss border, the travelers indulged in conversational fireworks that Picabia and Apollinaire honed to a fever pitch. The poet first read his long poem “Zone” on this occasion, the resounding capstone to his book Alcools. Soon afterward, he removed all the punctuation from the manuscript before it went to press.

Around the time of that car trip, Picabia began painting abstract pictures. Duchamp was moving closer to the anti-retinal position he held for the rest of his life; retinal art being for him that which only pleased the eye, and he would soon cease painting altogether. The friendship between Picabia and Duchamp amounted to a kind of cabal, in which they sharpened their native intelligence into complementary sets of surgical tools. Duchamp later called Picabia his copilot. They shared above all a “mania for change,” as Duchamp put it. “One does something for six months, a year, and one goes on to something else. That’s what Picabia did all his life.”

Possibly the most important factor for Duchamp in New York is that in this milieu he was not the little brother. Jacques and Raymond were eleven and twelve years older, respectively, and Duchamp revered them, having followed in their footsteps as an aspiring artist himself. The eminence of his brothers in the Parisian art world had not been an asset to Duchamp, however. Despite winning a medal from the Rouen Société des Amis des Arts around the time he graduated from the lycée in 1904, he failed the entrance exam to Paris’ École des Beaux-Arts. Undiscouraged and taken under the wing of his siblings who established an arts colony in Puteaux on the outskirts of Paris, his paintings were accepted annually to the Salon d’Automne from 1908. But his steady if unexceptional rise in the art world came to a sudden halt in 1912, when he decided to remove Nude Descending a Staircase from consideration for the Salon des Indépendants, after the organizers expressed doubts, suggesting he delete the title. His own brothers conveyed the grim request. “It was a real turning point in my life,” Duchamp recalled. “I saw that I would never be much interested in groups after that.” He went to Munich for a while, intentionally isolated and adrift but convinced of one thing: “Everyone for himself, as in a shipwreck.”

Another factor contributing to Duchamp’s European shipwreck was a growing attraction to Picabia’s wife, Gabrielle, to whom he professed his love in 1912. Although he arranged a clandestine meeting, there would be no consummation until a decade later, after she was divorced. Looking back, Buffet-Picabia marveled that “even now I find it really astonishing and very moving. It was utterly inhumane to sit next to a being whom you sense desires you so much and not even to have been touched.”

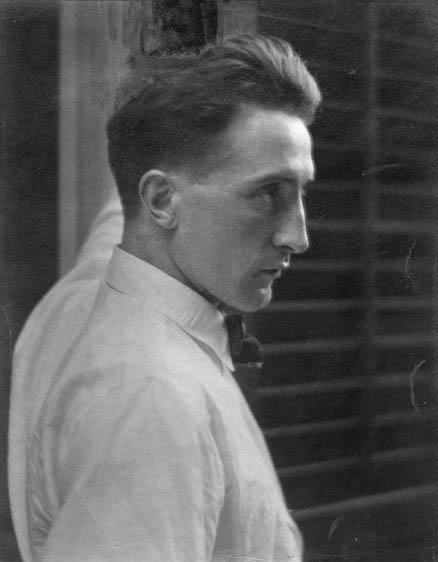

Something of this ardently romantic spirit was evident to the New Yorkers who met the newcomer, an effect doubled by his being a Frenchman. When Beatrice Wood met him late in 1916, she recalled: “We immediately fell for each other. Which doesn’t mean a thing because I think anybody who met Duchamp fell for him.” He had that effect on men as well, radiating an intellectual magnetism like some fourth dimension of the erotic. A photo by Edward Steichen conveys it best. Duchamp went so far, in fact, as to characterize that period of his life—when he was working on his most famous work, The Large Glass—in just such terms. “Eroticism was a theme, even an ‘ism,’ which was the basis of everything I was doing.” And much of it was being done with young women, who, it appears, he needed to make no effort to entice.

Marcel Duchamp, photographed by Edward Steichen, 1917.

Copyright © 2014 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Duchamp had an aura of taking everything for granted, including his own unplanned exaltation in the eyes of these Americans. Toward the end of his life, when asked what had satisfied him most, he replied: “Having been lucky.” He was not a schemer, and what little ambition he had for a career had been discarded back in France, supplanted by what looks like indolence but was probably patience. He was like a golden child who wanders untouched through the most fraught zones, impervious to the dangers, radiating a glow of immunity. He wasn’t a golden child, of course; Beatrice Wood, for one, noted the dark chill he carried within, faintly evident from time to time. He characterized himself much later as “enormously lazy. I like living, breathing, better than working.” It’s not surprising he’s been touted as the antithesis of the hyperproductive Picasso.

But it wasn’t sloth or indolence that brought Duchamp to New York. After all, crossing the Atlantic after the sinking of the Lusitania by a German torpedo took pluck; and shortly before he left he told a friend that staying in Paris would mean persisting in the usual career aspirations of an artist, seeking fame and fortune while at the mercy of wealthy patrons. Above all he loathed having to become a “society painter,” as he put it.

Duchamp stayed with the Arensbergs for his first month in New York. Like Buffet-Picabia, Louise Arensberg was a musician, and she’d already mastered the thorny piano pieces of Arnold Schoenberg (at a concert of Schoenberg’s music Kandinsky was emboldened to pursue the “emancipation of dissonance,” as the composer put it, in his painting). Louise didn’t drink, but her husband, Walter, obliged by drinking for two.

By the time Duchamp found his own place, a salon had blossomed around him. He quickly became the living god in the Arensberg shrine and, just as important, the social lubricant of a burgeoning avant-garde. With Duchamp at the helm—an “angel who spoke slang,” as Beatrice Wood put it, and a “missionary of insolence” someone else said—there developed a raucous spirit that was, to all intents and purposes, Dada without anyone being aware of Dada, because it didn’t exist yet, even in Zurich.

The intellectual ebullience of the Arensberg circle was most conducive to the conceptual wit Duchamp brought to the objects he called ready-mades. Back in Paris he had mounted a bicycle wheel on a stool, simply for the pleasure it gave him as it spun, like having a fire in a fireplace, he said. He’d also kept a bottle-drying rack at hand, just for the look. The first declared ready-made, though, was a snow shovel bought in a hardware store on Broadway in late 1915. In January he wrote his sister Suzanne in Paris, informing her of the purchase and the inscription he applied to the shovel, “In advance of the broken arm.” Recalling the items left in his Paris studio, he asked her to sign the bottle rack (“I’m making it a ‘readymade’ remotely”). He cautioned her on attributing any significance to this sort of thing. “Don’t try too hard to understand it in the Romantic or Impressionist or Cubist sense—that has nothing to do with it.” To the end of his life he insisted that ready-mades were chosen with indifference to any aesthetic qualities or question of taste.

Taste, whether good or bad, Duchamp thought merely a habit, rather like art itself. The mindless perpetuation of habits made him bristle, an opinion he shared with the Dadaists. Anyone now visiting the portion of the Philadelphia Museum of Art given over to the Arensberg collection, which houses the largest body of Duchamp’s work in the world, is likely to be impressed with something like the taste evident in the overall selection. Irony? Contradiction? Regardless, Duchamp’s greatest luck was escaping the dreaded role of society painter. Instead, he ended up with the Arensbergs—ready, willing, and able to be his personal patrons. Duchamp did almost anything to ensure the consistency of the relationship, even touching up a reproduction of the Nude, as consolation for the fact that Walter had been unable to lure it away from its original owner in San Francisco.

When Duchamp arrived in New York, he was as ignorant of English as Picabia. Picabia made no effort to learn the language, but Duchamp (being poor and practical) plunged right in, even though the Arensberg circle took French for granted. The poet Wallace Stevens reported to his wife how delightful it was to converse “like sparrows around a pool of water” in the Latin tongue during a long dinner with his former Harvard classmate Walter and the newly arrived artist. Some of the Americans who frequented the salon were less at ease, like William Carlos Williams, who felt himself chastened when he professed a fondness for one of Duchamp’s works hanging on the well, only to find the artist responding, “Do you?” with what the poet thought to be a superior air.

Duchamp’s relationship with Man Ray proved the most durable—and one that encouraged them both to bridge the linguistic gap, as neither knew the other’s language. Man Ray was a young artist living in what Duchamp perceived as wild and woolly New Jersey. He was married at the time to Belgian artist Adon Lacroix, but she was less interested in translating for his benefit than in her own conversations with Duchamp on the subject of favored poets, like Laforgue and Mallarmé. The two men had to content themselves with playing a game of tennis, with Man Ray giving a name to each pass and Duchamp repeating his new word yes. Their partnership, from there on out, would prolong that welcoming affirmation. For Duchamp, it was as though he’d found a vital balance to the sacred no he shared with Picabia.

Man Ray, a native New Yorker, was from an immigrant Ukrainian family named Radnitsky. By the time he met Duchamp, he’d shed the ethnic name and convinced the rest of his family to do so as well. (Man was short for Emmanuel.) Trained in technical aspects of art and design, he was lucky enough to discover Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery in 1911, when he was twenty-one. But nothing quite prepared him for the impact of the Armory Show, which stopped him in his tracks for half a year. He matured quickly after that, so that by the time he met Duchamp he was preparing his first solo exhibit at the Daniel Gallery in New York, resulting in a liberating windfall when the lawyer and art collector Arthur Jerome Eddy bought $2,000 worth of his paintings. With his eye for venturesome art, Eddy had previously bought two of the four Duchamp paintings exhibited at the Armory Show.

By the time of this eventful solo show, Man Ray had embarked on the path he’d become best known for, photography. He had a mentor in Stieglitz, but characteristically pragmatic, he took up the medium not for its creative potential but to document his paintings before they sold.

Man Ray’s propensity for mastering technical challenges reflects his temperament as well as his practical training in industrial art. Some of his paintings resemble stencils in the way they section off body parts into lozenges. Others, like the massive and vibrantly colored The Rope Dancer Accompanies Herself with Her Shadows, bring to mind dressmaking patterns, and Man Ray would soon be cutting out various supporting materials to add to the canvas. He also took up the airbrush, an industrial tool that proved just the ticket for the clean, quasi-photographic look he achieves in Admiration of the Orchestrelle for the Cinematograph, on which he used ink, gouache, and pencil to produce alphanumeric effects. Spending time with Duchamp, who around this time started laboring over his assemblage piece The Large Glass, affirmed Man Ray’s multimedia tendencies.

By this point Man Ray was making assemblages as well, like the disarming Self-Portrait consisting of a handprint centered between a bell button and a pair of ringers, which prompted critic Henry McBride to salute the artist’s enlistment of tactile sensation. Noticing that many visitors to the gallery were inclined to press the buzzer, McBride admitted to his own struggle to refrain.

Self-Portrait may be the clearest harbinger of the contributions Man Ray would make to Dada when he moved to Paris in July 1921, but other works were already treading into Dada waters. Some paintings looked almost as if he were copying the chance generated paper patterns of Hans Arp, though Arp wasn’t yet known in New York. And he anticipated by a few years the Berlin Dada vogue for automata, in yet another technical foray into the medium of the cliché verre, in which a drawing is incised onto a coated glass, which then acts like a photographic negative to produce a paper print. He was inching closer to the vistas photography would open up, but for the time being it served mainly as the medium in which he and Duchamp could perpetrate, document, and sanctify the antics that would eventually be recognized as Dada.

Ezra Pound, who knew both men later in Paris, admired their audacity. They have pushed art, he said, “to a point where it demands constant invention, and where they can’t simply loll ’round basking in virtuosity.” Pound makes no reference to Dada, but this passage nicely evokes the spirit of creative adventure characteristic of nearly all the Dadaists.

Dada was still on the other side of the horizon from the New York skyline. Arturo Schwarz, Milanese gallery owner and lifelong curator of Dada, asked Man Ray in his later years if he thought there had ever been Dada in America. “There was no such thing,” he emphatically replied. “You can put me down as having said that. I don’t think the Americans could appreciate or enter into the spirit of Dada.”

It’s true that most of what’s been identified as New York Dada was accomplished (or indulged in) by expats in the city during the war. Man Ray was the major exception. So bountiful were his artistic activities it’s easy to overlook his experiments with sound poems, nearly contemporaneous with Cabaret Voltaire. His denial of an American Dada makes sense in light of his move to Paris, where he was immersed in an avowed Dada movement, with Tristan Tzara at the helm. Man Ray quickly became a central figure in the cause (even before he arrived his photographs were on display at the Salon Dada Exposition International exhibition at Galerie Montaigne). So it was easy for him, decades later, to insist America had no Dada. At the time, shortly before leaving his homeland, Man Ray had written to Tzara, “Dada cannot live in New York. All New York is dada, and will not tolerate a rival.” Apparently he was coming around to the attitude of Picabia, who in 1920 had confided to Parisians that “in America everything is DADA.”

This was a theme that would shortly be taken up in the glossy pages of Vanity Fair (to which Tzara contributed accounts of Dada). In the February 1922 issue, Edmund Wilson observed that Parisians were worked up about the latest American folderol, and “young Americans going lately to Paris in the hope of drinking culture at its source have been startled to find young Frenchmen looking longingly toward America.” As for what Wilson took to be the latest fad, “the electric signs in Times Square make the Dadaists look timid,” sounding a theme also taken up by another American, Matthew Josephson, who was not only living in Paris but immersed in the inner sanctum of Dada. In July 1922, in the expatriate arts journal Broom, Josephson’s “After and Beyond Dada” surveyed the latest publications of Dada poets and found them caught up in a “search for fresh booty.” He observed, “The contemporary American flora and fauna are collected, in an arbitrary fashion, out of the inimitable films, the newspaper accounts, the jazz band, on the hunch that the world is on its way to being Americanized.”

But that was later, after the war reached its ignominious conclusion, and the survivors were glad to have it behind them. As these European pre-Dadaists romped around the United States, the fight was still raging—both in their homeland, and in the salons of New York, where the future of modern art in America was being decided.

In the summer of 1915, Picabia and Duchamp had just arrived in New York, and Man Ray was still living in an artist’s colony in Ridgefield, New Jersey. The scene was profiled in the Special Feature Section of the New York Tribune for Sunday, July 25, 1915, under the headline: “Free-Footed Verse Is Danced in Ridgefield, New Jersey.” The subhead went on at some length: “Get What Meaning You Can Out of the Futuristic Verse—Efficiency Is Its Byword and Base—It’s As Esoteric as Gertrude Stein Herself or a Loyd Puzzle—‘Others’ Is the Name of the Field Through Which You Must Wander to Grasp It.” The perpetrators of this new cult are described as dressing in “strange garb” of a “Chinese” sort, and wearing sandals. The reporter also lists the residents of the community, erroneously including William Carlos Williams (who lived nearby in Rutherford) and omitting Man Ray, a resident who was himself writing poems.

The author of the New York Tribune article made a point of mentioning Mina Loy, a regular of the Arensberg salon. Loy pushed all sorts of boundaries. Her frank “Love Songs” were brandished in the inaugural issue of the free verse journal Others, profiling “Pig Cupid,” his “rosy snout / Rooting erotic garbage.” The journal’s editor, Alfred Kreymborg, ran a slogan in every issue: “The old expressions are with us always, and then there are others.” It was a sentiment that could be applied to the whole milieu of Dada in New York. Besides Mina Loy, another of the poets who contributed such novel “expressions” to Kreymborg’s journal was Man Ray.

Man Ray and Francis Picabia were both prodigiously productive during this time, while Marcel Duchamp labored away fitfully at The Large Glass, baptizing a ready-made now and then. He was delighted when the Bourgeois Gallery included two ready-mades in its Exhibition of Modern Art. One, called Trébuchet (Trap), was a board with four metal coat or hat hooks and would have been inconspicuous were it mounted on a wall, near an umbrella stand, reverting, as it were, to its normative use. But Duchamp nailed Trébuchet to the floor near the entryway to the gallery, where it, nonetheless, went entirely unnoticed as “art” by most.

In any case, nobody viewing modern art at the Bourgeois Gallery in April 1916 was prepared to shift his or her gaze away from objects in frames or on pedestals. It would take a more dramatic intervention to press the point home. The opportunity, in fact, would come almost exactly a year later.

Shortly after the United States declared war on Germany on April 4, 1917, the Society of Independent Artists—an organization formed by Arensberg, Duchamp, Man Ray, and a few others—was preparing its first major exhibition. There was no jury, and anyone could exhibit work for a small fee.

Duchamp evidently decided to test the limits of this organization in which he was a presiding member. A week before the opening, after lunching with fellow artist Joseph Stella, Duchamp and Arensberg passed by the J. L. Mott Iron Works showroom at 118 Fifth Avenue, where Duchamp bought a flat-back Bedfordshire model urinal. Back in his studio he signed the name R. Mutt on the upper rim. Placed so, the signature meant the object had to be seen at an unfamiliar angle. He then arranged for Fountain, as he named it, to be delivered to the hanging committee, of which he was a member.

Artistically speaking, this was a shot heard round the world, its sonic boom still resounding. Fountain would become one of the most famous artworks of the twentieth century, a fact that would have outraged and depressed most of the artists in the Independents exhibition, to say nothing of the more conservative factions who were still ridiculing the Armory Show years later. Beatrice Wood witnessed a painter (George Bellows or Rockwell Kent, she couldn’t recall which) at his wit’s end, insisting to Arensberg that the obscene thing could never be shown. Walter pointed out that the fee had been paid, adding that, regardless, “a lovely form has been revealed” in an unsuspected place.

As it turned out, the more than twenty thousand visitors who roamed through the enormous exhibit—its 2,125 works arranged alphabetically by artist, beginning with the letter R—were spared an encounter with Fountain, which was denied entry in the end. Its rejection precipitated the resignation of Arensberg and Duchamp from the board of directors. The piece was last sighted in 291 Gallery, where Stieglitz photographed it in front of a painting by Marsden Hartley.

The original piece was gone, but it was certainly not forgotten. Duchamp began authorizing replacements in 1950, and by the time he died in 1968 more than a dozen were in circulation. Before then, Fountain was known strictly through Stieglitz’s photograph, printed in the second issue of The Blind Man, a short-lived journal edited by Duchamp with Beatrice Wood and Henri-Pierre Roché. The title affirms Duchamp’s “anti-retinal” approach to art. The photograph bore the caption, “The exhibit refused by the independents.” It was followed by a short article in variable type, “The Richard Mutt Case,” unsigned but probably by Duchamp. The article certainly reflects the aesthetic pioneered by his ready-mades: “Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view—created a new thought for that object.” In the word object lurks the verb, to object, which is precisely what that object provoked.

Such homonyms and puns were endlessly fascinating to Duchamp, albeit generally in French. One of his favorite authors was Jean-Pierre Brisset (1837–1923), whose speculative etymologies led him to conclude that humans had evolved from frogs. His abiding principle was that “all the ideas expressed with similar sounds have the same origin and all refer, initially, to the same subject.” Given the riotous homophonic propensity of French, Brisset fancied a necessary connection between expressions like laid en la bouche (ugly in the mouth) and lait dans la bouche (milk in the mouth). Duchamp’s inclination to think of the erotic as an ism may have been inspired by Brisset’s theory that “sexual force alone creates all human speech, as it does all humans.” Accordingly, “all words were suckled, aspirated, licked, and there is not one that did not enter the mouth through one of these actions.” If that isn’t explicit enough, try this: “The pronoun I designates the sexual member, and when I speak, it is a sexual organ, a virile member of the eternal-God which acts through his will or his permission.” Duchamp made no pretense to speak or act on behalf of a higher authority, but he was consistently clear about his determination to shake off the hidebound habits of personal taste, a position that led him to take up mechanical drawing to, as he put it, “forget with my hand.”

At the heart of Duchamp’s enterprises and escapades is his mental agility, his ability to think and act not with ideals and principles in mind, but as an exercise of athletic prowess. If you can think it, you can express it; or, more often in Duchamp’s case, if you can say it you might then begin to think it (Picabia later came up with the slogan “Thought is made in the mouth,” happily reiterated by Tzara). Its principle of forward motion was expressed in another item from The Blind Man, a poem called “For Richard Mutt” by the painter Charles Demuth, which concludes:

For some there is no stopping.

Most stop or get a style.

When they stop they make a convention.

That is their end.

For the going every thing has an idea.

The going run right along.

The going just keep going.

Among the other contributions to the Mutt issue of The Blind Man is Stieglitz’s radical proposal that future exhibitions should present the art anonymously, a prospect that some Dadaists might have acclaimed. “Thus each bit of work would stand on its own merits. As a reality. The public would be purchasing its own reality and not a commercialized and inflated name.” Vanity Fair editor Frank Crowninshield’s laudatory letter takes up the theme of the journal’s editorial (“The only works of art America has given are her plumbing and her bridges”): “If you can help to stimulate and develop an American art which shall truly represent our age, even if the age is one of telephones, submarines, aeroplanes, cabarets, cocktails, taxicabs, divorce courts, wars, tangos, dollar signs; or one of desperate strivings after new sensations and experiences, you will have done well.” A similar note was struck in The Little Review by Jane Heap, who lamented the timidity of American artists “terrorized by the power of plumbing systems and engines,” urging them instead to seek out alliances with scientists and engineers.

If the infamous Fountain quickly attained the replenishing aura of a fons mirabilis, a similar object from the same year escalates the gambit. This was a plumbing trap mounted on a miter box, named God. This sculpture implied that the alimentary function of the inner organs bore their divine mission as gravitational destiny, as if the famous biblical text read “Let there be digestion” instead of “Let there be light.”

The painter Morton Schamberg photographed God in front of one of the many machine paintings he executed under the influence of Picabia. The idea behind the piece has been traced to the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, routinely if inadequately characterized as “colorful” in the bohemian sense. This German poet and artist arrived in New York in the year of the Armory Show, where she met and promptly married a German baron who abandoned her the next year when the war broke out, hoping to enlist but ending up interned in a French prisoner-of-war camp for the duration. Meanwhile, the baroness twisted like a corkscrew through the New York avant-garde until her return to Europe in 1923.

When Duchamp arrived in New York the baroness quickly fixated on him and they became as close as he’d allow. She would trumpet her attraction to him with the refrain “Marcel, Marcel, I love you like hell, Marcel,” impetuously declaiming it at the Arensbergs and elsewhere. While some could be cowed by her sexual voracity, Duchamp remained poised in his resistance and earned her respect for it. Duchamp’s preoccupation with bride and bachelors in his Large Glass inspired her to write, a tad reproachfully, “thou becamest like glass,” and “now livest motionless in a mirror!”—as if he were the “unravished bride” of Keats’ famous Grecian urn. Joyously responsive to the theme of the female machine introduced by Picabia in works like his detailed drawing of a spark plug with the title Portrait of an American Girl, the baroness promoted herself as “proud engineer” unashamed of her “machinery.” With scatological clarity, she reasoned, “If I can eat I can eliminate—it is logic—it is why I eat!” It was only natural, she insisted, that to lavishly extol the pleasures of the palate extended to reports of “my ecstasies in toilet room!”

These ruminations appeared in the July 1920 issue of The Little Review, pointedly preceding the chapter of Joyce’s Ulysses in which Leopold Bloom masturbates on the beach, aroused by the undergarments of a coy maiden nearby. The Little Review, which proudly bore on its cover the slogan “Making No Compromise with the Public Taste,” had been serializing Ulysses, beginning in 1918. This ended when the postmaster general seized four issues, refusing to distribute them, one of them the July issue with the baroness’ cheeky prelude to Bloom’s self-administered “relief.” As a consequence, the review and its editor, Margaret Anderson, went to trial in 1921 over this reputedly obscene material. During the trial—which led to the discontinuation of Ulysses in serial form—the judge refused to permit passages from Joyce’s work to be read aloud in the courtroom on the grounds that this would somehow besmirch the virginal ears of Anderson, who had (so the judge must have presumed) somehow published the offending text without reading or comprehending it.

Jane Heap, coeditor of The Little Review, was a tireless supporter of the baroness, responding to the suppressed issue by opening the next with a portrait of the flamboyant German. But this was a fairly docile photographic silhouette, revealing nothing of her ostentatious couture. She was a performance artist of everyday life, though there was nothing “everyday” about her costumes. Djuna Barnes characterized her in the New York Morning Telegraph Sunday Magazine as “an ancient human notebook,” adorned with “seventy black and purple anklets clanking about her secular feet.” She appeared at a fancy dress benefit concert in a “trailing blue-green dress and a peacock fan. One side of her face was decorated with a canceled postage stamp (two-cent American, pink). Her lips were painted black, her face powder was yellow. She wore the top of a coal scuttle for a hat, strapped under her chin like a helmet. Two mustard spoons at the side gave the effect of feathers.” On another occasion she wore a dress clattering with seventy or eighty toy soldiers, locomotives, and similar items, also “a scrapbasket in lieu of a hat, with a simple but effective garnishing of parsley,” while dragging along on a single leash half a dozen mangy little dogs. (She was a collector of animal life, even feeding and sheltering rats.)

Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven made a fitful living as an artist’s model, though by this time she was in her forties and her somewhat unconventional looks were going. The artist George Biddle recorded his astonishment when she appeared in his studio one day seeking work. Sweeping open her scarlet raincoat with a “royal gesture,” Biddle beheld: “Over the nipples of her breasts were two tin tomato cans, fastened with a green string about her back. Between the tomato cans hung a small bird-cage and within it a crestfallen canary. One arm was covered from wrist to shoulder with celluloid curtain rings, which later she admitted to have pilfered from a furniture display in Wannamaker’s. She removed her hat, which had been tastefully but incongruously trimmed with gilded carrots, beets and other vegetables. Her hair was close cropped and dyed vermilion.” She was endlessly inventive in fabricating ornaments, like Limbswish, a metal spring conjoined to a curtain tassel, named for the motion it displayed when worn on the hip. The baroness’ sartorial flair was a perpetual advertisement for a personality best described as far out in an almost galactic sense. Poet-doctor William Carlos Williams, chastened by her ardent advances, allowed that she was “courageous to an insane degree.”

Jane Heap celebrated Baroness Elsa as “the first American Dada”—overlooking her origins, conspicuously retained in her thick accent and unorthodox written English. In the baroness, “Dada is making a contribution to nonsense.” This estimate appeared in a special Picabia issue of The Little Review, when the journal was caught up in the Dada “season” unfolding in Paris, and it reveals by omission that the earlier activities of Duchamp, Man Ray, and Picabia himself were not yet linked to Dada. When Duchamp and Man Ray made a film of the baroness shaving her pubic hair in 1921, did they regard it as a Dada event? There is evidence they did not: Man Ray pasted a still from this film into the letter he wrote Tzara in Paris, informing him “dada cannot live in New York.”

Yet other signs point to a steady assimilation of Dada by these New York artists. Man Ray’s letter to Tzara coincides exactly with his and Duchamp’s production of the journal New York Dada. What’s more, an entire page (of four overall) in this singular production was given over to Tzara’s “authorization” of the use of the word Dada. “Dada belongs to everybody. Like the idea of God or of the toothbrush,” he wrote, approving this American embrace of Dada. After all, it was “not a dogma nor a school, but rather a constellation of individuals and of free facets.” Intriguingly, Tzara addresses his response to “Madame.” Perhaps to emphasize the gender, a photo by Man Ray appears sideways at the top of the page, in which a naked woman stands partially obscured behind a hat rack. The madame in question may also be the one seen peering out through a shapely female calf, in a double exposure by Alfred Stieglitz on the previous page, with the slogans “WATCH YOUR STEP!” and “CUT OUT DADYNAMIC STUFF!”

Most signally, though, New York Dada features Duchamp on the cover and two photos of the baroness on the last page. Amidst a grid of letters printed upside down, reading “new york dada april 1921,” and running the full fourteen inch length of the cover, is a photograph of a perfume bottle labeled Belle Haleine (sweet breath), with an oval portrait of Duchamp in drag in his role as Rrose Sélavy. In another instance of cross-gender appointments, the photos of the (nude) Baroness are accompanied by an ad for the upcoming Société Anonyme exhibit of “Kurt Schwitters and other Anonymphs”—Schwitters’ fame having reached America with Anna Blume, courtesy of Katherine Dreier.

Duchamp’s newfound alter ego as Rrose Sélavy presaged the role that portraiture would play for the rest of his life. At a point when he’d abandoned painting altogether (his last canvas was Tu’um, executed in 1918 at the request of Dreier, to fill a long thin space above a bookshelf), the question of what an artist would produce instead of art was intriguing. There were the ready-mades, but Duchamp decided that there had to be strict limits on the number of objects that could be so designated. There was The Large Glass, which kept precipitating a sprawl of enigmatic notations, most of which suggested a much grander outcome than anything that could be rendered visible. In a few years he would begin producing “rotoreliefs,” discs that when spun added vertigo to the puns inscribed on them. And from time to time he would idly pursue a commercial enterprise, as when he proposed to Tzara that they produce a line of bracelets with the four letters d-a-d-a attached. But the Belle Haleine perfume bottle opened the door to a creative prospect already unintentionally under way.

The press coverage of Duchamp’s sojourn in New York had already created a persona that fluctuated wildly. The choirboy countenance in Vanity Fair was hard to reconcile with a photo in the New York Tribune under the headline “The Nude-Descending-a-Staircase Man Surveys Us.” Far from gazing into the camera, the artist sprawls on a recliner with eyes closed. Whether or not Duchamp himself suggested this pose, it conveniently emphasizes the anti-retinal orientation of an artist no longer disposed to paint. And yet, Belle Haleine is a genuine fabrication in another domain, taking art into the realm of advertising, where “image” is all. Artists have sometimes found employment in the “artistic illustration” side of advertising—Andy Warhol, most famously—but Duchamp’s perfume bottle was linked to no product other than the persona he adopted for the pose as Rrose. It was also a collaborative gesture, one of many undertaken with Man Ray over the years.

As the title of a 2009 exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery made clear, “Inventing Marcel Duchamp” may have been his most consistent creative indulgence in the realm of image making. Duchamp had always been rankled by the French expression bête comme une peinture (stupid as a painter), and while he tried to add as much cognitive complexity to his canvases as possible, there was a limit to mere appearance. But people can’t help being seen, and Duchamp was no recluse. After the Armory Show he was a celebrity. In the wake of the press coverage, he realized he was bound to make an appearance, one way or another, so making that appearance became an artistic prerogative. He was surely inspired to take it up a notch by the uninhibited baroness and the flamboyant Mina Loy, who once was photographed in profile to show off an earring she’d made from a thermometer.

Duchamp, Picasso, and their generation lived out their lives in the Kodak century, so there are countless photos of them. But whereas Picasso was more frequently caught in snapshots, spontaneously cavorting on a Riviera beach, Duchamp posed right up to the end of his life. He posed for famous fashion photographers like Edward Steichen and Arthur Penn, but they themselves were operating with full knowledge of Duchamp’s legacy of self-production for the camera. He obligingly went down a flight of steps for a photographer illustrating the Life magazine article “Dada’s Daddy” in 1952. He even suggested posing in the nude for the session (fat chance, given that this was Life and not The Little Review). Despite the lavishly illustrated article, Duchamp was predictably pegged “pioneer of nonsense and nihilism” for the middlebrow American readership.

Man Ray documented Duchamp with a star shaved into the back of his head and, on another occasion, with his hair lathered up into devil’s horns for the “Monte Carlo Bond” certificate (1924)—in addition to several sittings with Duchamp posing as Rrose Sélavy. The most feminine version involved a woman’s hands reaching around from behind to primp Rrose’s fur. Then there was the “Wanted $2,000.00 Reward” poster, based on a joke souvenir into which Duchamp inserted his own mug shots. Duchamp made several return trips to Paris as its own Dada scene was heating up, and his unflappable demeanor and uncanny ability to get the most out of the least effort proved spellbinding to his French peers. Soon there would be no peers, only Duchamp himself, professionally inscrutable—and, for that matter, devoted no longer to art, it seemed, but to chess.

What a strange sojourn his time in America had been—and what a strange artistic borderland Dada inhabited there. Dada in New York wasn’t even regarded as Dada until the news of its Swiss eruption trickled in, and New York Dada was published as a late saluting shot across the bow. The high spirits of Duchamp and Picabia lingered in the air, though. The war was still raging, but it would be Picabia, with his itinerant lifestyle, who ended up transmitting these high spirits back across the Atlantic to Dada’s original homeland in the Alps. Exchanging issues of Dada publications through the mail was one thing, but Picabia’s personal appearances in New York, Zurich, and Paris would make Dada seem destined for a global triumph.