By serendipitous coincidence, the term Dada was conceived in Zurich in April 1916, the same month Duchamp mentioned his ready-mades to a reporter for the Evening World in New York. The link between the two words would not become evident for a while, and then only circuitously.

Later in 1916 the Mexican-born artist Marius de Zayas, whose Modern Gallery had featured Picabia in its first show, published African Negro Art: Its Influence on Modern Art, a subject that preoccupied Tristan Tzara. The two men struck up a correspondence, and by the end of the year, The First Celestial Adventure of Mr. Antipyrine—with its manifesto-speech declaring Dada “our intensity”—was circulating in the Arensberg circle, courtesy of de Zayas. By then, the Arensbergs’ salon had reached a state of near incandescence with its combination of artistic brilliance and intellectual momentum, fueled by excellent food and intoxicants. This Dada, from Switzerland of all places, had found the perfect nesting ground.

As it migrated around the earth, Dada resisted the usual properties of time and space. It appeared in different places at different times, rarely following a linear chronology or causal sequence. To go forward with the story, then, requires a leap back in time, in order to arrive at the consequential meeting of Tzara and Picabia—the two men whose combined efforts would conjoin the Old and New Worlds under the banner of Dada.

Shortly after Picabia returned to New York in June 1915, while ostensibly on his military mission, he ended up sharing a house with the Cubist painter Albert Gleizes and his wife, Juliette Roche, who wrote much of her sole book of poetry, Demi Circle, while there. She found Picabia’s lifestyle challenging. “Picabia could not live without being surrounded morning and night by a troop of uprooted, floating, bizarre people whom he supported more or less,” she recalled. “The whole artistic Bohemia of New York plus several derelicts of the war.” With this ragtag band in residence, and Picabia’s unrestrained and uninhibited appetites, there were incessant appeals to join the frolic: “Noise at any time or knocks on the door, ‘We are having a party. Come down.’” Although Roche and her husband would soon tire of the frenetic pace they found in the New World, it was initially captivating, a place, as Roche wrote in a poem, in which:

the woodwinds of the Jazz-Bands

the gin-fizzes

the ragtimes

the conversations

embrace every possibility

Roche, Picabia and other wartime exiles like Duchamp, Jean Crotti, and Mina Loy were habitués of de Zayas’ Modern Gallery, where a new oversized journal named 291 (honoring Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery) was under way. Among its notable innovations were pictorial word compositions called psychographs, fielding bits of conversation and psychological introspection amidst great black lozenges threatening to blot out the page altogether. In “Mental Reactions,” Agnes Ernst Meyer drew on the experiences of women everywhere to chronicle the fits and starts of self-recognition in a patriarchal world. “At best her life, her whole life, was nothing but his introduction to himself.” Meyer is left wondering, at the end, about women’s plight: “Why do we all object to being the common human denominator?” Juliette Roche adopted the format of the psychograph for several poetic portraits in Demi Circle, including one depicting the expats’ favorite haunt, the Breevort Hotel on Fifth Avenue a few blocks north of Greenwich Village.

Meanwhile Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia was growing concerned about her husband’s prolonged stay in New York, so she made the transatlantic crossing only to find Picabia caught up in a neurasthenic whirlwind—sleepless, overstimulated, firing on all cylinders. His wife had walked in on a creative orgy.

To say that Picabia was spewing out artworks is misleading, because what he was doing required the precision of a watchmaker. He had to be on top of his game when it came to producing art, even if everything else in his life slid into dissipation. The fifth issue of 291 consisted of portraits (de Zayas, Stieglitz, and Paul Haviland among them) modeled entirely on mechanical parts. On the last page, in both French and English, de Zayas acclaimed Picabia the natural successor to Stieglitz. “Of all those who have come to conquer America, Picabia is the only one who has done as did Cortez. He has burned his ship behind him,” he wrote. “He has married America like a man who is not afraid of consequences. He has obtained results.” A self-portrait accompanied portraits of Stieglitz, de Zayas, and Haviland, along with the provocatively titled spark plug, “jeune fille Americaine dans l’état de nudité” (who, it’s been suggested, may have been Agnes Meyer, a beauty apparently immune to the artist’s customary allure).

Picabia was given the last word in the final issue of 291 in February 1916, in which he reiterated the stance he’d developed around the time of his first American trip—that is, painting needed to absorb the visible world into a complex of mental and emotional responses in its quest to be “the most truthful and the purest expression of our modern life.” The mind’s eye, not the retina, was the agent of vision. Picabia never adopted the resolutely anti-retinal position of his friend Marcel Duchamp, but painstakingly drawing a spark plug and calling it a young American woman in a state of nudity was his way of giving a high five to that other nude descending a staircase—and a wink and a nod to the “bride” Duchamp was busy courting in his never-completed The Large Glass.

Buffet-Picabia prevailed upon her husband to go to Cuba and fulfill his military mission by procuring sugar reserves for France, thereby avoiding court-martial or worse. His mission completed, the pair went on to Barcelona, where they found Gleizes and Roche along with other friends from prewar Paris days.

Apart from indulging in an affair with Marie Laurencin, a painter who’d been the mistress of his friend, poet Apollinaire, Picabia found the Catalan port depressing. Desperate to spark his life, he decided to launch his own magazine, naming it 391, as a numerical successor to the recently folded 291. Writing to Stieglitz, he allowed that “391 is not as well done, but it is better than nothing, for truly here there is nothing, nothing, nothing.” The refrain—nothing, nothing, nothing—would be tellingly repeated several years later in Picabia’s “Dada Cannibal Manifesto.” In the inaugural issue of 391, he declared that his artistic platform, honed to a fine pitch in America, would “only use symbols drawn from the repertoire of purely modern forms,” namely machines.

It was a curious enterprise. Picabia had the means to bankroll a handsomely produced publication but hardly the temperament to adhere to a production schedule. Or maybe 391 was a genuine periodical in that it came out periodically—that is, from time to time, with nineteen issues between January 1917 and October 1924. The format varied over the years. The first seven issues were roughly fifteen by ten inches, then swelled into various larger formats, sometimes up to twenty-three inches tall. Whatever its dimensions, it was always exquisitely designed and generously filled with Picabia’s wit and wickedness.

If it seemed his private forum for thumbing his nose at the world, more discerning readers recognized his gift for sizing up (and squashing) artistic and intellectual pretensions. In the first issue, after opening with a poem in which, with mock patience, Picabia took swipes at rival artists Robert Delaunay (mischievously suggesting that he was going to Lisbon to decorate the façades of all the buildings in the city) and Picasso (“Picasso repents” read another item, reporting that the Cubist master had enrolled as a student in the École des Beaux Arts).

In the midst of these shenanigans, Picabia related a curious incident in which a painting he’d shipped to Paris was confiscated at the border and sent to the Minister of Inventions because it was suspected of depicting a compressed air brake. During wartime something resembling a technical drawing was bound to raise suspicions, but this episode points to a lingering problem that would play out for years to come, as in the confiscation of a Brancusi sculpture by American customs agents who decided it was not art but industrial material subject to duty. Defiantly, the covers of all but one of the first nine issues of 391 featured Picabia’s mechanomorphic drawings, including the exquisite depiction of a flamenco dancer (no. 3), a ship’s propeller wittily labeled “ass” (no. 5), and a lightbulb labeled “Américaine” through which can be seen the words flirt and divorce (no. 6).

Picabia churned out four issues of 391 in the three months he spent in Barcelona and three more in the summer back in New York. In addition to containing artwork and occasional contributions by others, the magazine served as a forum for his poetry. He’d started writing around the beginning of the war, and the trickle became a torrent, especially during neurasthenic episodes when he was medically advised to refrain from painting. (His second collection, Poems and Drawings of the Daughter Born Without a Mother, was dedicated to his doctors in New York, Paris, and Lausanne.) The poems could hardly be read as evidence of a cure. Quite the contrary, they’re a farrago of agony, intemperance, and obscurity. The abstraction he’d pioneered as a painter seems to have flowed freely into his word compositions.

A third of the poems in his first book, Fifty Two Mirrors, are from issues of 391. If they generally fall under the heading “Frivolous Convulsions,” the title of a poem published in the second issue, aspects of his life and temperament are faintly visible through the haze. He may portray himself as a “freeloading angel” and refer to “my indecent gibberish”—or in a wry self-assessment, “I have but one tongue / With bad manners”—yet he’d suddenly arrive at the most lucid pledges: “I want my life for myself,” “one must be many things,” and “I demand the ravishing.” Inveterate womanizer that he was, Picabia made no attempt to conceal his extramarital escapades:

The full distance

For a single pleasant hour

Of vertiginous passion.

Frequent references to opium disclose another weakness:

Smokes

Like a crack in the

Superterrestrial brain

The full register of his neurasthenic travails is on display in these poems, chronicling the heights of creative, erotic, and drug-induced euphoria and plumbing the depths of fatigue and depression down to that realm where an idea is nothing but an “animal squeal.” Although he may not intend it, surely Picabia is among those “Artists of speech / Who have only one hole for mouth and anus” (from the very first poem he ever published, in English translation, in Man Ray and Duchamp’s magazine The Blind Man in May 1917).

Besides sex and drugs, Picabia’s poetry bore signs of another telltale American influence. This was pointed out in the single issue of another little magazine Rongwrong, which Duchamp published in May 1919. There, Duchamp printed a letter by his near namesake Marcel Douxami (leading many to assume he’d penned the epistle himself). Douxami, an engineer from New Jersey, thought Picabia’s poems mere trickery, but made an interesting topical observation. “Picabia’s poetry seems to me to spring from American music—a syncopated beat with a melody that the composer either wasn’t able or didn’t know how to get down.”

Douxami was on to something, though he clearly hadn’t yet heard or processed the new word jazz, a term beginning to circulate in tandem with that other four-letter word dada. Indeed, Man Ray’s aerograph painting Jazz dates from the same year as Rongwrong and might just as plausibly have been named Dada, given the nearly synonymous implications of these two new words.

For many, jazz and Dada seemed interchangeable. “Dada Putting the Jazz into Modern Verse,” ran a headline in the Boston Evening Transcript in 1921, characterizing the new phenomenon in subsections titled “An Intellectual War-Baby” and “Shell-Shocked Literature.” In Europe, posters for Dada activities sometimes included the word jazz as part of the overall typographic soup. In 1922 there was a journal named Dada-Jazz in Yugoslavia, far from the circuits in which jazz musicians were performing.

Given these early uses of the term, it’s likely jazz arrived piggyback on Dada. But Dada itself was in some sense beholden to American initiatives like jazz. Hugo Ball reflected on this shortly before he started up Cabaret Voltaire, when he wrote a note in his diary chastising himself and his cronies for their supercilious Eurocentrism. “Art must not scorn the things that it can take from Americanism and assimilate into its principles; otherwise it will be left behind in sentimental romanticism.” Americans themselves, with their innovations like jazz, were harbingers of radical change and personified cultural chic, with which the artistic avant-garde struggled to keep pace.

One American student studying abroad made an early impression in England as a proponent of Americanism. During a college debate at Oxford in 1914, “I pointed out,” the student T. S. Eliot wrote to the folks back home, “how much they owed to Amurrican culcher in the drayma (including the movies) in music, in the cocktail, and in the dance. And see, said I, what we the few Americans here are losing while we are bending out energies toward your uplift . . . we the outposts of progress are compelled to remain in ignorance of the fox trot.” He assimilated jazz as a flourish of his verbal calling card, assuring an English friend in 1920 that, in future visits, “it is a jazz-banjorine that I should bring [to a soirée], not a lute.” By that point, Eliot was a celebrated poet, associated with the vanguard movement Vorticism.

At the Cabaret Theatre Club in London, the turkey trot and bunny hug were thought of as “Vorticist dances,” in a milieu described by one participant as “a super-heated vorticist garden of gesticulating figures, dancing and talking, while the rhythm of the primitive forms of ragtime throbbed through the wide room.” Reviewing Diaghilev’s ballet Parade with music by Eric Satie in a 1919 London performance, F. S. Flint wondered what to call it: “Cubo-futurist? Physical vers-libre? Plastic jazz? The decorative grotesque?”

Such terminological indecision was rampant among those documenting current events, so it’s not surprising that the impact of avant-garde performances contemporaneous with the spread of Dada carried this loose association with jazz. A few years later there was also the novelty element of jazz in which Dada performances also seemed to specialize. So when entertainer Madame Power in London was advertised with her “jazz-dancing elephants,” how could it not sound like Dada had come to town?

On the Continent, jazz arrived as accessory to the new dances—an extension, in effect, of the animation with which the musicians performed. “They enjoy themselves with their faces, with their legs, with their shoulders; everything shakes and plays its part,” exclaimed the enthralled Yvan Goll. Goll had witnessed similar high spirits at Cabaret Voltaire, which Hans Richter characterized as “a six-piece band. Each played his instrument, i.e. himself, passionately and with all his soul.” Huelsenbeck’s passion for the big drum and “Negro rhythm” presages Marcel Janco’s 1918 painting, Jazz 333. Arp, Hausmann, Schwitters, and other Dadaists were keen on the latest jazz dances long after Dada subsided. Insofar as Dada was perceived as part of a modernistic complex that included Cubism and Futurism, the visual contortions common to all three movements could be seen as infused with the spirit of jazz. “Like a Cubist painting by Picasso, a watercolor by Klee,” wrote bon vivant and fashion guru F. W. Koebner in Berlin in 1921, “seemingly senseless and discordant, jazz is in fact thoroughly harmonious by means of its discord.”

Koebner’s numerous books on popular dance may have reached George Grosz and Raoul Hausmann, who were dedicated to the latest dances, and Arp, too, was an enthusiastic dancer. With his penchant for all things American, Grosz was a devotee of jazz. After Czech composer Erwin Schulhoff was exposed to jazz by Grosz in 1919, he set Hans Arp’s Cloud Pump to music and composed a five-minute, scrupulously notated “orgasm” for a female soloist called Sonata Erotica. Schulhoff hailed from Prague, where a general initiative called Poetism absorbed Dada as part of the cultural tendency of the age, in which jazz, Charlie Chaplin, sports, dancing, music hall, and the circus were extolled as “places of perpetual improvisation,” valued precisely for the fact that they were unpretentious and, above all, not art. “Clowns and Dadaists taught us this aesthetic skepticism,” wrote Karel Teige, one of the ringleaders of Poetism.

Aesthetic skepticism is what Gilbert Seldes recommended in his influential 1924 book The Seven Lively Arts, disparaging the “vast snobbery of the intellect which repays the deadly hours of boredom we spend in the pursuit of art.” By “we” he meant Americans, “inheritors of a tradition that what is worthwhile must be dull; and as often as not we invert the maxim and pretend that what is dull is higher in quality, more serious, ‘greater art.’” This was a view shared by Dadaists, not that Seldes knew anything about Dada. But his advocacy of “lively arts” like cinema, jazz, variety shows, and other purportedly lowbrow entertainments would have been welcomed in Dada circles. The national qualities he enumerates—“our independence, our carelessness, our frankness, and gaiety”—characterize the way Duchamp and Picabia experienced America, finding it a quintessential and entirely unconscious manifestation of the Dada spirit.

When the Picabias made their way back to New York from Barcelona in March 1917, they promptly “became part of a motley international band which turned night into day,” Picabia’s wife Gabrielle recalled. Their group was composed of “conscientious objectors of all nationalities and walks of life living an inconceivable orgy of sexuality, jazz and alcohol.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, she soon returned to Europe to be with their children.

After Gabrielle’s departure, Picabia rented an apartment with composer Edgard Varèse, where the two quickly established a norm—in the pre-air-conditioned New York summer—of forfeiting clothes, even receiving visitors in the buff. Among them was Isadora Duncan, herself no prude, and she promptly claimed Picabia as the next in her long retinue of lovers. One day she phoned Duchamp, asking him to pay a visit precisely at noon. When the young artist arrived, not knowing what to expect but probably anticipating some erotic turn of events, she marched him straight to her bedroom—to the closet, actually, which she opened with a flourish to reveal Picabia perched on a stool, having a cup of tea. “Isadora hid me here without telling me why,” he said.

Soon after this titillating exchange, an oft-cited scandal imputed to Dada occurred, although its protagonist had little to do with Dada. Arthur Cravan—who, as a point of personal pride, was distantly related to Oscar Wilde—had made a name for himself issuing a solo magazine called Maintenent (Today), a no-holds-barred enterprise that likely inspired Picabia when he began his own 391. Cravan’s specialty was insulting artists. “I feel nothing but disgust for a painting by a Chagall,” he would write, or “Metzinger, a failure who has snatched at the coat-tails of cubism.” “A bit of good advice,” Cravan extended to these unfortunates, “take a few pills and purge your spirit; do a lot of fucking or better still go into rigorous training”—like Cravan himself, in fact, who had some success as a boxer. “Genius is nothing but an extraordinary manifestation of the body,” he wrote.

Cravan spent some time in Barcelona, where he was knocked out in a legendary fight with heavyweight champion Jack Johnson and came to the attention of that city’s temporary resident, Picabia. In the inaugural issue of 391, Picabia inserted a fanciful item about this colorful athlete: “Arthur Cravan is another who’s on the transatlantic. He’ll be giving some lectures. Will he be dressed as a man of the world or a cowboy? For his departure he opted for the latter, making an impressive appearance on horseback, with three shots from his revolver.”

Once in New York, Cravan began mingling with the Arensberg circle, making unwelcome advances to Mina Loy, who would nevertheless come around—the couple wed and had a daughter, born after Cravan disappeared mysteriously in the Gulf of Mexico and was never heard from again.

In June 1917, though, while Cravan was alive and kicking, Duchamp arranged for him to give a lecture at the Independents at Grand Central Palace, the Premier Exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists, where of course Fountain was not on display. Cravan was so drunk when he arrived, an hour late, that he could barely stand at the podium, where he delivered a resounding blow before starting to disrobe while shouting obscenities. The audience began streaming for the exit as the police arrived and shut down the proceedings. “What a wonderful lecture,” Duchamp later remarked. This occasion has been routinely recounted in books about Dada, becoming in effect a canonized scandal for those content to associate Dada with scandals and nothing but.

The Cravan “lecture,” which fueled the superficial perception that Dada frequently engaged in juvenile misbehavior, is a bit of urban folklore that’s no more part of Dada than the parties attended by Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald in the roaring decade of Prohibition. But it does have the virtue, in the present context, of indicating the desperate alcoholic torpor afflicting the whole community of exiles as the war dragged on. What began for many of them as a stimulating interlude in New York was beginning to look like a tawdry lifestyle.

After his indulgent summer, Picabia finally had enough, rejoining his family in Europe in October. But his travails and exploits continued. A month after returning to Paris, he met Germaine Everling, whose marriage was on the rocks. With his customary erotic alacrity, he managed to sweep her off her feet, and ten days later the couple had an extramarital honeymoon precisely where his honeymoon with Gabrielle had been.

Neither this nor any of his other exploits were hidden from his wife, who was increasingly called upon to nurse him through his bouts of neurasthenia and depression, which had reached such a severe pitch that he consented to a prolonged treatment in Switzerland—but not before cementing the relationship with Everling that would eventually end his marriage. As Everling later recalled, Gabrielle told her outright that Picabia was hers for the taking, but she stressed that his mental health was precarious. Insightful and accommodating as always, she suggested Everling pay daily visits just to keep up Picabia’s spirits, assuring her they were above bourgeois conventions.

In February the family went to Lausanne so that Picabia could be treated by the eminent Dr. Brunnschweiller, with Everling following in June. Picabia met her at the station, admitting his condition had taken a turn for the worse because he’d been shot at several times by a fellow artist outraged to find Picabia sleeping with his wife. There’s a certain picaresque aspect to Picabia’s womanizing, but this episode is a reminder of just how reckless he could be. It was this volatility that had driven Gabrielle to leave him in New York the previous year. A biographer puts it well: “Picabia, with or without depressions, allowed himself the life of a true bachelor and did his best to put into practice all sorts of separating ploys and extenuating experiences in order to attain that state of supreme freedom which is the patrimony of the superman.” As the Nietzschean reference suggests Picabia was accustomed to living “beyond good and evil.” But that was also a no-man’s-land in almost a military sense.

Maybe Picabia should be counted among the war casualties suffering not from shell shock but from the accelerated churn of his own unchecked appetites. To use the machine vocabulary that he deftly assimilated in his art, Picabia was a human drill bit, boring into the future. Serendipitously, the one person most disposed to revel in his spirit was living nearby in Zurich—a dapper Rumanian, anxiously eyeing the horizon to see where, and how, Dada might take on new life.

During the run of Galerie Dada, Tristan Tzara was busy consolidating international contacts, bombarding them with press clippings of Dada exploits, and soliciting contributions to a new Dada publication. His ministrations proved vital because he found the combatant nations only too happy to supply propaganda materials, without postal charge, as a routine expenditure of the war effort. Art somehow passed muster under this category. So the gallery was plentifully stocked with works from Germany, France, and Italy, amicably sharing the exhibition rooms. It was propaganda all right, but “propaganda for us.”

Now, with Ball once again out of the picture, Tzara was poised to embark on his biggest propaganda campaign. His calling card was the inaugural issue of Dada, published in July 1917. It wasn’t all that imposing, running to just seventeen pages, with texts on the left facing artworks on the right-hand pages—little more than a slim profile of what had transpired since Cabaret Voltaire was published a year earlier. Its diminutive size, however, made it cheap to mail—after all, that was its main purpose—and it was commensurate with other journals of the international avant-garde published during the war, like Pierre Albert-Birot’s SIC and Pierre Reverdy’s Nord-Sud in Paris, Neue Jugend under its new editor Wieland Herzfelde in Berlin, and De Stijl, launched by Theo van Doesburg in Leiden in October.

Thanks to his determination to establish contact with vanguard enclaves around the world and promote the Dada cause, Tzara gradually became aware that interesting things were under way in New York and the artist Francis Picabia was involved. In August 1918, hearing that Picabia was in Switzerland, Tzara wrote to introduce himself and ask for a contribution to Dada, describing it broadly as a publication “on modern art” (adding later that its goal was to represent “new trends”—albeit “according to a criterion that shall remain secret”). The two men hit it off right away, sending each other publications and manuscripts, and by November Picabia confessed “I live quite isolated from everything, and your letters are a sympathetic contact that does me good.” (He was also frank about his neurasthenic problems and ongoing psychiatric care.) They shared an abiding affection for Picabia’s old friend Apollinaire, recent victim of the Spanish flu epidemic that swept the world after the war. The sudden loss affected Picabia deeply because his wife had dined with the poet in Paris less than a week before he died, and he’d spoken of visiting them soon in the Alps.

In their correspondence, Picabia and Tzara come across as kindred spirits almost furtively seeking heat and light, each of them depressed and dispirited in their isolation. “May I call you my friend?” Tzara writes in early December, and Picabia responds, warmly if somewhat dutifully, “Dear sir and friend.”

At the center of their mutual stimulation is a series of disclosures central to Tzara’s view of Dada as a destructive force, a view most congenial to Picabia, the intellectual and artistic swashbuckler. Tzara suggested that their budding friendship drew on a “different, cosmic blood,” giving him “strength to reduce, decompose, and then order into a strict unity that is simultaneously chaos and asceticism.” Picabia in turn expressed his appreciation for Tzara’s manifesto, which he thought “expresses every philosophy seeking truth, when there is no truth, only convention.” Tzara responded by applauding his friend’s “individual principle of dictatorship, which is simplicity, suffering + order.” Few at the time would have been capable of discerning in Picabia’s ravaged and raving poetry anything of the sort, but Tzara’s own poems were similar testimonies to his peculiar amalgam of exasperation, personal torment, and free-spirited sense of wonder. Where William Blake distinguished his Song of Innocence from Songs of Experience, Tzara and Picabia freely mingled them within the same poem, even in the same line. Their meeting by correspondence was a sort of alphabetic mingling, inciting in each man the feeling that the other was capable of finishing his sentences. But this shared sensibility pitched the two headlong into a kind of jubilant despondency—and how many people could really deal with that?

At the root of Tzara’s particular negativity was the fortifying genius of Dada itself, for which negation was a positive measure: “I’m telling you,” he confided to Picabia, “the only affirmation for destructive work (which all art radiates) is productivity, and that can be found only in strong individuals”—individuals honed on a Nietzschean self-regard, like Picabia. So Tzara could appeal to Picabia with disclosures the older man was uniquely prepared to understand. “I’ve never passed up an opportunity to compromise myself, and besides devilry, it is an efficient and recreational pleasure to wave magic handkerchiefs before the lanterns of cow eyes”—a rueful reflection of the low regard Tzara had for the local Swiss who comprised the audience for Dada.

By this point Picabia was urging Tzara to pay an extended visit to Paris, to which he was about to return. Tzara relished the prospect: “Perhaps we’ll be able to do beautiful things, since I’ve a stellar, insane desire to assassinate beauty.” These confessions caused Picabia to delay his return to Paris in order to pay a personal visit to Tzara in Zurich. Correspondence was one thing, but a personal meeting now seemed paramount for both men. What was intended to be a quick visit of a few days extended to three weeks, weeks that “just flew by” wrote Picabia afterward.

Picabia’s visit to Tzara and his dwindling circle of Dadaists in Zurich was like a key fitting into a lock. There was perfect reciprocity all around, a mutual stimulation they all lapped up. “Picabia’s first appearance, plying us all with champagne and whisky in the Élite Hotel, impressed us in every possible way,” Richter recalled. In addition to his wit and audacity, Picabia was wealthy, unorthodox, a free spirit—and that rara avis, “a globetrotter in the middle of a global war!” But his creativity was inseparable from his unremitting nihilism. He possessed “a radical belief in unbelief” that excited Tzara, but sent Marcel Janco into a spiral of depression. Richter himself reflected, “I met Picabia only a few times; but every time was like an experience of death.” (Richter would eventually end up in New York, where he made films with Duchamp and others associated with Dada late in their lives, and he recognized that Duchamp and Picabia walked a very fine line in which they repudiated art by making it, although what they made of it did not comply with artistic conventions, the ready-made being a prime example.)

Behind Picabia’s captivating darkness, there was exuberance—at least for those capable of withstanding it. The dynamic momentum of negation needed a positive counterforce, a beneficent receptivity. This was one of the paradoxes on which Dada was perched, almost like those publicity hounds in the Roaring Twenties who perched atop flagpoles with the nonchalance of someone lounging in an easy chair. Tzara captured a bit of this in his chronicle of the Zurich scene for Huelsenbeck’s Dada Almanac in 1920, intriguingly identifying Picabia as “the anti-painter just arrived from New York” whose arrival provoked the next step in exuberant negation. “Let us destroy let us be good let us create a new force of gravity NO = YES”—and, without a pause or any distinguishing punctuation, he segues into another subject altogether:

Dada means nothing life Who? catalogue of insects

Arp’s woodcuts

each page a resurrection each eye a daredevil-leaping

down with cubism and futurism every sentence a blast of

an automobile horn.

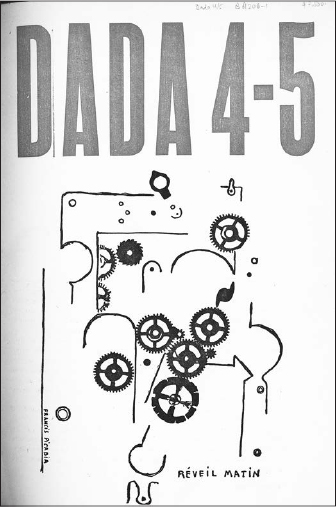

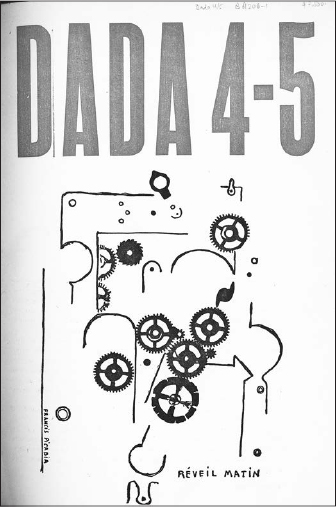

Arp and Tzara visited Picabia at his hotel. “We found him busy dissecting an alarm clock,” Arp recalled. “Ruthlessly, he slashed away at his alarm clock down to the spring, which he pulled out triumphantly. Interrupting his labor for a moment, he greeted us and soon impressed the wheels, the spring, the hands, and other secret parts of the clock on pieces of paper. He tied these impressions together with lines and accompanied the drawing with comments of a rare wit far removed from the world of mechanical stupidity.” Arp added, with an artist’s insight, “He was creating antimechanical machines,” and in his unbounded creativity Picabia released “a teeming flora of these gratuitous machines.” Not surprisingly, one of these decomposed clocks adorned the cover of Dada 4/5.

Dada 4/5 (May 1919), cover by Francis Picabia.

Copyright © 2014 Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Tzara had become absorbed in Picabia’s poetry, which could be more easily transmitted through the mail than his artworks. But he had seen some of the paintings, which had been solicited for an exhibit by a Zurich dealer and then peremptorily returned to Picabia without explanation—and with the obligation to pay return post. Meeting the artist in person elevated Tzara’s admiration, and he started looking out for opportunities to circulate his friend’s work in any medium. In February 1919 he mentioned that “a certain Mr. Benjamin (writer-journalist)” of Berne was interested in purchasing Daughter Born Without a Mother. The person in question was Walter Benjamin, one of the most brilliant intellectuals of the postwar decades. At that point, doing graduate work in Berne, he found himself living next door to Ball and Hennings, who naturally apprised him of the recent Dada activities in Zurich.

Benjamin did not succeed in acquiring Picabia’s fanciful daughter, but he managed to buy a little painting by Paul Klee called Angelus Novus. It made its way into the “Theses on the Philosophy of History” he wrote as the shadow of another world war loomed, leading to his untimely death fleeing the Nazis in 1940. In Klee’s angel he found this allegory:

His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

This chilling passage has been justly celebrated. But has its affinity with—maybe even its source in—Dada ever been recognized? Benjamin’s “theses” famously include the aphoristic observation, “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism”—a view rehearsed, performed, shouted, and whispered as Dada wended its way from Zurich to Berlin and beyond.

Benjamin recognized the relevance of Dada to his messianic outlook on modern political barbarity. Dada is central to his famous essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproducibility,” where it serves as a model of the shock effects of modern media in general: “The work of art of the Dadaists became an instrument of ballistics. It hit the spectator like a bullet.” It was part of an arsenal for ringing the alarm bell. Wake up, Benjamin heard Dada call out, the time is later than you think. In his theses on history, Benjamin exhorted readers to realize that “the ‘state of emergency’ in which we live is not the exception but the rule.” By the time he wrote this, he’d spent the better part of a decade compiling a vast archive of notes for The Arcades Project, a portrait of Paris as capital of the nineteenth century, launchpad of the twentieth.

Benjamin characterized his Arcades Project as “an alarm clock that rouses the kitsch of the previous century to ‘assembly.’” He conducted much of his research in the fabled City of Light during the heyday of Surrealism. Although not an insider of the movement, he was in touch with Breton, Tzara, and others and wrote a profile of Surrealism in 1929 for a German audience in which he celebrated its “profane illumination.” The Surrealists, he concluded, “exchange, to a man, the play of human features for the face of an alarm clock that in each minute rings for sixty seconds.” It’s not too much to imagine that Picabia’s dismembered apparatus on the cover of Dada left an imprint on Benjamin’s imagination commensurate with the gears Tzara and Arp saw anatomically revealed in a Zurich hotel.

There was a final hullabaloo after Picabia’s visit to Zurich in January 1919. It would prove to be the apotheosis of everything cultivated in Cabaret Voltaire, combined with the experiments of Galerie Dada.

On April 9, 1919, in the large Kaufleuten Hall—allegedly seating a thousand—the final event of Zurich Dada was held. Tzara planned out the program with fanatical precision but could not achieve all his intentions. As he wrote Picabia during preparations, “This is the first time I regret not having learned how to ride a bicycle; I wanted to come on stage on a bicycle, get off, read, get back on, leave: curtain. Now I’ll have to hire someone who’ll walk around on the stage while I read.” Tzara also confided to his newfound guru of negation the hidden ennui that motivated him. “I live from one amusing idea to another. But know that this game will also bore me before long.”

That underlying spirit of engaged indifference, or animated boredom, was quickly picked up by the Kaufleuten audience, providing the Dadaists with the bull’s-eye they’d been seeking all along. The occasion had all the earmarks of former Dada events, with a few additional ingredients applied in just the right measure.

Arp and Richter painted a massive backdrop, mainly black but with abstract lumps that made the whole thing look like a cucumber patch run amok. Some of the Laban ladies danced with African masks. Music by Schoenberg, Satie, and resident composer Hans Heusser was reprised, along with poems by Arp, Huelsenbeck, and Kandinsky. Familiar fare for some, but as this was a full house, the performances were certainly a new experience for most.

The program opened with a dry lecture on abstract art by the Swede Viking Eggeling, who’d recently come to the Dada scene and whose interest in developing a universal vocabulary of abstract forms hit a chord with Hans Richter. The two would soon move to Berlin and take up an entirely new pursuit: making films. The first section of the program concluded with another simultaneous poem by Tzara, this time on a grand scale with twenty performers, their cacophony matched by a chorus of catcalls from the audience. An intermission gave the seething mood of the restive crowd a chance to subside.

The program resumed with a brief excursus in audience baiting by Richter (“elegant and malicious,” thought Tzara) before another round of music, poetry, and dance. Then came Walter Serner, a dyed-in-the-wool nihilist, a human curse incarnate. A wartime refugee who’d come to Switzerland from Berlin, Serner voiced skepticism toward Dada in his journal Sirius. Nevertheless, he proved willing to grace this grand occasion with a manifesto, “Final Dissolution,” also translated as “Last Loosening.” Dressed in the most elegant attire, Serner came on stage carrying a headless tailor’s dummy, to which he presented a bouquet of flowers where the head would have been. Then, conspicuously sitting in a chair with his back to the audience—now in a deep hush, straining to hear—he began reading his manifesto.

It’s hard to convey the tight spiral of Serner’s text as it keeps cancelling itself and everything else, combining the scholastic rigor of Kant with a steady drizzle of insolence. In any case, the poison quickly penetrated the normally polite Swiss audience until it exploded when Serner made reference to Napoleon as a “really clever lad.” As Richter comments in his history of Dada, “What Napoleon had to do with it, I don’t know. He wasn’t Swiss.”

At Serner’s mention of Napoleon, the audience was instantly transformed into a crowd of thugs, ripping apart the balustrades and chasing Serner from the premises. “This is our curse, to conjure the UNPREDICTABLE,” Richter felt at the time. But Tzara thought it the ultimate Dada triumph. “Dada has succeeded in establishing the circuit of absolute unconsciousness in the auditorium.” In a note describing the scene for Dada 4/5, he suggested Serner incited in the audience nothing less than “a psychosis that explains wars and epidemics.”

Amazingly, after the pent-up agitation burst, the show resumed and concluded without further incident. It’s as if the audience had been drained and had no strength left to rise up against another round of free dance with African masks, another spirited manifesto by Tzara, and aggressively rhythmic but atonal music by Heusser. The final Dada unguents were lavishly applied to the open sores of the Zurich natives, spent and chastened by their own unleashed aggression. When the show was over, the performers thought Tzara had gone missing, but found him in a restaurant nearby counting the take, the largest windfall Dada had managed in its three years.

After this “last loosening” in Zurich, little remained for Dada in the Swiss capital. The war had ended only months before, and Switzerland was beginning to empty out as refugees made their way home, or elsewhere. Many of the hard core of original Dadaists joined this exodus, transmitting the “virgin microbe” to fresh, unsuspecting populations.

By the end of the year the Janco brothers were in Paris, where Tzara followed early in 1920. Arp, being a German national, couldn’t get a visa to return to Paris for another five years, but the life he’d embarked on with Sophie Taeuber more than compensated. The most that he and Tzara could manage in the wake of the Kaufleuten extravaganza was to plant an item in the press to keep Dada before the public eye. Distributed to dozens of papers around the world was a news flash, “Sensational Duel,” in which it was reported, “There was a pistol duel yesterday on the Rehalp near Zurich between Tristan Tzara, familiar founder of Dada, and Dada painter Hans Arp. Four rounds were fired, and in the fourth exchange Arp was slightly grazed on his left thigh.” Adding mischief to this fanciful report, the item indicated that Picabia had come all the way from Paris to act as a second for Arp, while Swiss writer J. C. Heer served in that capacity for Tzara. Poor Heer suddenly gained local notoriety and wrote to the newspapers declaring his complete mystification—and innocence. Meanwhile, Tzara and Arp frequented their usual cafés, with no evident acrimony between them. In fact, they issued a disclaimer, stating that the bogus news flash had been planted by one of their enemies.

Circulating false reports of a duel was clearly a step down from the “circuit of absolute unconsciousness” unleashed in the Kaufleuten audience. After that triumph, the remaining Dadists found themselves trapped in the middle-class environment of Zurich, its bourgeois coziness a reminder of how improbable it was that Dada had erupted there at all. In fact, most Dadaists were themselves born middle class, and pursuing a life of art meant a renunciation of that birthright. Rather than conformism, though, something else in that background contributed to Dada’s identity. Never before had a dominant class invested so much in perceiving itself as a norm while being fascinated by individuals or lifestyles that deviated from that norm. A familiar, if extreme, example of a beguiling deviant is the American outlaw, who seems to work overtime to attain what others manage by being unexceptional. It’s not surprising that George Grosz idolized American gangsters, cultivating an American wardrobe to look the part. The daring and guile of the outlaw crossed over into Dada, which exalted destruction as a virtue.

After the Kaufleuten performance, as Tzara basked in the cynical company of Serner, he adopted destruction as the characteristic expression of Dada. “To be dangerous is the most pointed probe,” he wrote in the next Dada journal, Der Zeltweg. In the same pages, Serner paraded his sharp wit at length, tossing off pithy sayings with the vigor of someone hammering a nail in a coffin. “The ultimate disappointment? When the illusion that one is free of illusion reveals itself as such,” he wrote, and “one becomes malicious out of boredom. Then it becomes boring to be malicious.”

Tzara’s embrace of destruction alienated him permanently from Janco, who was still fuming nearly forty years later when he distinguished between creative and destructive tendencies in Dada, resenting Tzara’s propensity for negation. But Janco was already at odds with Tzara anyway, reproaching him for not disclosing the extent of his international contacts. Tzara, he thought, was promoting Dada far and wide as his personal calling. But if Tzara was smitten by mayhem—as though obeying Joseph Conrad’s exhortation in his novel Lord Jim: “in the destructive element immerse”—he knew there was an honorable foreground.

Tzara had honed his poetic sensibility on the French Symbolists, chief among them Stéphane Mallarmé, who said “destruction was my Beatrice”—that is, his inspiration (Beatrice being Dante’s muse). But destruction of what? He managed to produce his poems, he said, “only by elimination.” In an era when poetic rhetoric heaped analogy on analogy, adding fussy decoration to any mood, Mallarmé went in the opposite direction, reducing his verses to such dense, compact shapes they’re barely readable. The mind bounces off their diamond surfaces. Such work anticipated the anti-art/anti-literature achievement described by Parisian Dadaist Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, “destroying the usual effect of language and giving it an effect more certain, but also more perfidious, that of dissolving thought.”

Now that Tzara had experienced total immersion in the destructive principle onstage as well as in print, he set his sights on the grandiose prospect of Dada invading the world. For the moment, however, he found himself stuck in Switzerland, a land of cuckoo clocks and lederhosen—all too far from the paroxysm of Berlin, or the Paris of his youthful dreams.