Dada’s inaugural year in Paris had both energized and enervated the participants. On one hand, Dada was the creative whirlwind they’d longed for; on the other, it threatened to become routine. A permanent rebellion wasn’t a dream come true after all. Later on, André Breton characterized Dada as a state of expectancy, preparation for something else. When the alternative finally appeared late in 1924, he named it Surrealism and spent his remaining forty years leading the movement. But as the Dada “seasons” rolled on, Surrealism was still in the future—and Dada still had more to accomplish in Paris.

As 1921 commenced, the Littérature group meeting regularly at Café Certa (already included in guidebooks as a place frequented by the infamous Dadaists) reconsidered how to proceed. The confrontational soirées of the previous year had, in retrospect, all too clearly followed the program pioneered by Tzara. It was time to try something different. Finally, on April 14, the first in a proposed series of Dada “visits” to sites of negligible interest was held. The announcement read: “The transient Dadaists in Paris, wishing to remedy the incompetence of suspect guides and cicerones, have decided to undertake a series of visits to chosen locations, in particular to those which really have no reason to exist.” On a rainy day the Dadaists led a small group of sodden spectators to the modest chapel of Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre, where Ribemont-Dessaignes provided commentary for various architectural features by reading entries at random from a Larousse dictionary.

A few weeks later the Dadaists presented an exhibit of art by Max Ernst at the Au Sans Pareil bookstore. (Sans Pareil, meaning “unparalleled,” would become a leading publisher of Dada titles.) This occasion reinforced the still controversial foreignness of the Dada movement, as Ernst was German. What’s more, he’d been denied a visa because of his Dada activities in Cologne, so he wasn’t on hand for his own show.

Advertised as “beyond painting,” the show featured works that, numbered with bus tickets, were described in the exhibit’s poster as “mechanoplastic plasto-plastic paintopainting anaplastic anatomic antizymic aerographic antiphonaries and sprayed republican drawings.” Certainly the pieces were unlike anything seen in Paris before. Instead of pictures, they seemed like laboratories in which you beheld a parallel universe being smelted before your eyes, or a hothouse where poisonous plants were bred, taking on humanoid characteristics. (Ernst would have been an ideal illustrator for those lugubrious tales by Nathaniel Hawthorne, like “Rappaccini’s Daughter.”) To Picabia’s catalogue of mechanomorphic works, these by Ernst teased mechanism into organism. He was called “a scissors-painter.”

An alchemical garden in always the best man wins (title in lower-case English) sprouts an array of ambiguous interspecies shapes, combining flowers with firearms. The Bedroom of Max Ernst houses a bear and a sheep at the far end of a chamber long enough to be a bowling alley, while the foreground is populated with a bat, a snake, a fish, and a whale. But these creatures were not to scale, as if to suggest that the dimensions of animal life were susceptible to psychotropic adjustment. Ernst’s medium was collage, with lots of overpainting. Using this method, he populated his paintings with deviant and unique life-forms. Ernst’s creativity extended to the titles, the inscriptions of which were rendered as visible components of the pictures, like Cuticulus plenaris, Sleuths, Vegetable Sheaves, and Adolescent Female Dadaists Cohabit Far Beyond the Permitted Extent—a title that could apply to the ensemble as a whole. His resources resembled those of Kurt Schwitters, raiding the heap of print culture, plucking pulp images for deviant repurposing. His goal, said Ernst, was “to transform into a drama revealing my most secret desires, that which had been nothing but banal advertising pages.”

During the opening of Ernst’s exhibit, the Dadaists in the gallery deliberately engaged in moronic behavior, each enacting an assigned routine with the mechanical regularity of a clock. Two of them repeatedly shook each other’s hands; another like an auctioneer called out the number of pearls worn by ladies as they entered. Breton chewed on matchsticks like an old cowhand, and Ribemont-Dessaignes intoned the dull slogan, “It’s raining on a skull.” As if these antics didn’t sufficiently single them out from the crowd, all the Dadaists dressed in black with white gloves.

Their shenanigans provided a contrast to the paintings hanging on the walls, with their ethereal aura. Unbeknownst to the organizers, this exhibit of Ernst’s works injected the bacillus of an eventual Surrealism into Dada. More than any other artist, Ernst brought an unrivaled prowess of visual imagination to Dada and then to Surrealism—and his prominence in both movements has caused many historians to collapse the two into one.

A cache of works by Ernst was originally viewed by the Dadaists in a meeting at Picabia’s house, after which Breton wrote to André Derain that Picabia was sick with envy, sensing his eminence as the foremost Dada artist in Paris was no longer secure. For Breton, on the other hand, Ernst’s impact was definitive, as important to art as Einstein to physics. Although Breton was making his living at this point as a consultant on literary and artistic investments to Jacques Doucet, the couturier whose vast collection is now a primary archive of Paris Dada, he had not yet presented his views about art in public.

For Ernst’s exhibition at Au Sans Pareil, Breton provided a short text to accompany the checklist of works. Breton presents Ernst as an artist made possible by cinema, dispelling “the swindling mysticism of the still life” on a trajectory that may even emancipate us, he suggests, “from the principle of identity.” The terms in which he spells out this prospect amount to an early draft of Surrealism, here construed under the auspicies of Dada:

The belief in an absolute time and space seems to be vanishing. Dada does not pretend to be modern. It regards submission to the laws of any given perspective as useless. Its nature preserves it from attaching itself, even in the slightest degree, to matter, or from letting itself be intoxicated by words. It is the marvelous faculty of attaining two widely separated realities without departing from the realm of our experience, of bringing them together and drawing a spark from their contact; of gathering within reach of our senses abstract figures endowed with the same intensity, the same relief as other figures; and of disorienting us in our own memory by depriving us of a frame of reference—it is this faculty which for the present sustains Dada.

For the moment, the knack of conjoining discrepant realities seemed most vividly rendered in the art of Max Ernst.

Ernst’s impact was rivaled by that of two preeminent New York Dadaists: Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp. Man Ray arrived on July 22, on a sojourn bankrolled by an American benefactor. It was just a few months after the Ernst exhibition. Duchamp met him at the station and took him straightaway to the Dadaists gathered at Café Certa, where the group commenced to make an all-nighter of the occasion.

For the time being, Man Ray, who had yet to learn French, could only communicate through Duchamp, but the art he brought with him spoke more vehemently than anything he could have said. Coming in the wake of Ernst’s “being-objects” (a concept coined later for Surrealism), Man Ray offered an equally original world that was all the more marvelous for having no overlap whatsoever with the artist from Cologne.

“Man Ray is the subtle chemist of mysteries who sleeps with the metrical fairies of spirals and steel wool,” wrote Ribemont-Dessaignes. “He invents a new world and photographs it to prove that it exists.” Hans Richter called Man Ray “the matter-of-fact realist of the irrational,” and making reference to the hero of Wagner’s epic Ring cycle, he elaborated: “Like Siegfried anointed with the dragon’s blood, Man Ray, being fried in the hot oil of Dada, hears the mute hissing of suppressed utilitarian objects. An anti-Woolworth’s.” For this “magician of uselessness,” ordinary objects harbored incalculable depths. Innocent surfaces were repositories of—not guilt, but some oblique shadow that tainted yet retained the innocence. In Man Ray’s objects, “the splendor of the commonplace practicality drops its trousers and shows its poetical backside.”

It was inevitable, given these accolades, that the Dadaists would exhibit Man Ray’s work in December. It was a sensible complement to earlier exhibits of Picabia, Ribemont-Dessaignes, and Ernst and the Salon Dada exhibit held in June, which fielded an impressive array of artworks from America, Germany, Italy, and France, making patent the fact that Dada was genuinely international.

Although Man Ray never gave up the medium—painting—that he was supposed to be practicing in Paris, he’d been increasingly absorbed in multimedia explorations in New York, and in Paris he began concentrating on photography. For the Dada-sponsored show at Librairie Six, a new bookshop opened by Soupault, the works consisted mainly of paintings and aerographs.

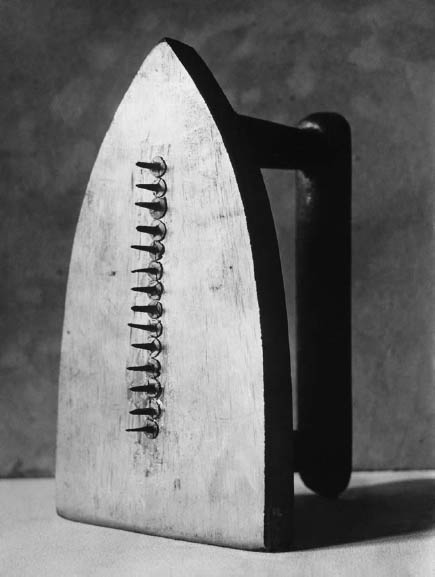

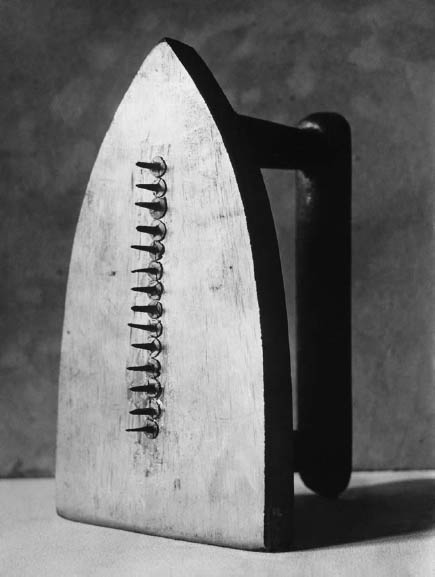

This show would produce one serendipitous concoction that was not listed in the catalogue, because it was created the day the exhibit opened. While hanging the artwork at Librairie Six, Man Ray struck up a conversation with a man who spoke excellent English. He turned out to be the composer Erik Satie. The two went out for a drink, and on the way back passed a hardware store where, with Satie’s help, Man Ray bought a flatiron, some tacks, and glue. He attached the tacks down the middle of the iron and gave the object to Soupault, but not before photographing it. The object, suitably named Cadeau (gift), disappeared, periodically replaced through the decades by knockoffs (each dutifully photographed), becoming the artist’s signature piece. Years later, in his eighties, he authorized and signed an edition of five thousand, which sold for $300 each.

Befitting a Dada event, the art on display in Librairie Six was obscured by as many balloons as could be crammed into the shop, squeezed together by the incoming crowd. At a predetermined signal, the Dadaists started popping the balloons with their cigarettes. The Dada spirit also was evident in the biographical note composed by Tzara for the catalogue: “Monsieur Ray was born goodness knows where. After being a coal merchant, a millionaire several times over, and chairman of the chewing gum trust, he decided to respond to the Dadaists’ invitation and exhibit his latest works in Paris.” More than a half-dozen texts in the catalogue suggest that Man Ray’s work, like that of Max Ernst, served as a stimulus to the production of writing—a reminder of the literary orientation of Paris Dada. Purportedly swearing off literature—and despite a range of abject responses to a forum in Littérature on the question “Why do you write?”—the Dadaists kept falling back on what they did best.

Man Ray, Gift, 1921.

Copyright © 2014 Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Before its arrival in Paris, Dada had been consistently presented in the language of inconsistency. Its provocations used language to undermine the semantic authority of language. The sense it made was always precarious, if not outrageous, but in the process the normal hankering for linguistic stability came to seem equally absurd. Jean Paulhan, in the Dada journal Proverbe, wrote: “My interest is in demonstrating that words do not translate thoughts (as with telegraphic signals or the signs of writings) but are things in themselves, material to be worked on, and difficult at that.”

Whether or not Dadaists elsewhere shared Paulhan’s interest in concretizing words and separating them from thoughts, the issue of language was closer to the center of Parisian Dada simply because most of the participants were—in that time-honored bourgeois phrase—men of letters. They might aspire, like Aragon and Breton, to fit the bill while resisting further production of literature, but they couldn’t help themselves. Cubist artist Albert Gleizes noticed the discrepancy between their vitriol and their publications, which “rather recall the catalogues of perfume manufacturers. There is nothing in the outward aspect of these productions to offend anyone at all; all is correctness, good form, delicate shading, etc.”—the key term being outward aspect. Still, they wrote, they published, and eventually saw the question of literature as such dragged into the Dada orbit, where its viability came under unprecedented scrutiny.

No one felt the literary mission more acutely than Breton. A few weeks after the Ernst exhibit opened, he presided as judge at a mock trial of eminent writer and parliamentarian Maurice Barrès, accused of having denied the anarchist-socialist outlook of his youth. The man himself was in the south of France at the time: no matter, a dummy sufficed. But this was no parody. The somber procedure was conducted like a real trial, with the various parties dressed in official robes. Not everyone was as keen on the idea as Breton. Picabia refused to take part, making a dramatic exit from the scene even before the proceedings got under way, when poet Benjamin Péret put in an appearance as an Unknown Soldier. At the time, a public debate was raging over an initiative to deposit the body of an unknown French soldier beneath the Arc de Triomphe, but Péret’s appearance put a match to the fuse. Wearing a gasmask and a German uniform, he goose-stepped onstage. Dozens of patriots in the audience responded with a spontaneous chorus of “La Marseillaise,” contributing an ominous prelude. When the actual trial commenced, a pall hung over the proceedings.

Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes proved less than committed to his assigned role as prosecutor. “Love, sensitivity, death, poetry, art, tradition and liberty, individual and society, morals, race, homeland. But what does Dada think of these pretty objects, Dada that judges Barrès?” he asked in his closing speech. “Gentlemen, Dada does not think, Dada thinks nothing. It knows, however, what it doesn’t think. Which is to say, everything.” How can Dada, he seemed to be saying, judge anyone or anything but itself?

Several of the participants in this performance realized that Dada and not Barrès was on trial. Tzara acted the part, much to Breton’s chagrin. “My words are not mine,” he insisted. “My words are everybody else’s words: I mix them very nicely into a little bouillabaisse—the outcome of chance, or of the wind that I pour over my own pettiness and the tribunal’s.” Not truth, in short, just “the commodities of conversation.” Breton was livid at Tzara’s behavior, seething at his refusal to play his designated role as witness for the prosecution. This was clear from the beginning, when he said no to the standard legal question about telling the truth and nothing but. “I don’t trust justice, even if it’s been conceived by Dada,” he countered. “You will agree with me, your Honor, that we’re all just a bunch of bastards,” dragging Breton by implication down into the muck of pure Dada noncompliance and revealing that the organizer of this fiasco was a dubious Dadaist. As Ribemont-Dessaignes sharply put it, Breton “adopted a bourgeois point of view toward Tzara’s conduct.”

In early 1922 Breton followed up the Barrès trial with another ill-fated initiative, organizing an event that would seem to fly in the face of every prior Dada manifestation. It was to be called “Congress to Determine the Aims and the Defense of the Modern Spirit.” In order to enhance its authority, he managed to interest prominent figures across a spectrum of the avant-garde to serve as organizers: Jean Paulhan of the Nouvelle Revue Française, Amedée Ozenfant of L’Esprit Nouveau, the painters Robert Delaunay and Fernand Léger, composer Georges Auric, and erstwhile Dadaist Roger Vitrac, who would later go on to found the Alfred Jarry Theatre with Antonin Artaud.

Not surprisingly, the other Dadaists balked at the prospect of such a venture. Unwilling to denounce the Barrès trial outright, Tzara wrote a polite letter explaining his reluctance to be involved. He summarized his position the next year in an interview: “Modernism is of no interest to me, and I think that it would be a mistake to say that Dadaism, cubism, and futurism rest on a common foundation,” he reflected. “These latter two tendencies were based on an idea of intellectual or technical perfection above all, whereas Dada never rested on any theory and has never been anything but a protest.”

Breton, overreacting to Tzara’s demurral, rallied the organizers of the modernist congress to issue an insulting press release: “At this time the undersigned, members of the organizing committee, wish to warn the public against the machinations of a character known as the promoter of a ‘movement’ coming from Zurich, which demands no other designation, and which today no longer corresponds to any reality.” The italics effectively acknowledged the growing suspicion that Dada was mortally ill if not defunct.

Breton endorsed the notion that Dada shared something with other tendencies in modern art, particularly Cubism and Futurism, and that this general trend merited investigation. He continued these ruminations when he accompanied Picabia to Barcelona for an exhibit of the artist’s works at Galerie Dalmau in November 1922. He gave a lecture called “Characteristics of the Modern Evolution and What It Consists Of.” He reiterated his view that Cubism, Futurism, and Dada were “part of a more general movement” and made known his alienation from Tzara. “Yes, Tzara did walk for a time with that defiance in his eye,” he informed his Catalan audience, “and yet all that wonderful self-assurance could not bring him to stage a veritable coup d’état. It’s just that Tzara, who had eyes for no one, one idle day took it into his head to have some for himself.” Eager to expunge Tzara from the ranks of inspirational figures, Breton credited Duchamp as having “delivered us from the concept of blackmail-lyricism with its clichés,” though it was Tzara who actually led the way where poetry was concerned.

Still under the thrall of Dada’s appetite for destruction, Breton envisioned the modern “movement” culminating in some violent rupture and even went so far as to declare: “It would not be a bad idea to reinstitute the laws of the Terror for things of the mind.” Internalizing the French Revolution as the standard for cultural significance, Breton was characterizing Dada as if it were a heedless monarch when, in March, he objected to its “omnipotence and tyranny.” In September he made the terms even more explicit, consigning Dada to a merely preparatory role in some larger venture: “Never let it be said that Dadaism served any purpose other than to keep us in a state of perfect readiness, from which we now head clear-mindedly toward that which beckons us.” A few months after the Barcelona lecture, he made a veiled reference to “that disquiet whose only flaw was to become systematic,” in which his evident reluctance to pin it all on Dada suggests a faint acknowledgement that the sin of being systematic fell more squarely on his own shoulders than on Tzara’s.

Nobody was less disposed to being systematic than Picabia (Breton noted, approvingly, that “the man who provides the greatest change from Picabia is Picabia”). The painter cast a wary glance over the plans for the congress as evidence of some inexplicably puerile compulsion. “This Congress of Paris would probably be to my liking if my friend André Breton managed to toss all our ‘modernist celebrities’ into the melting pot and in doing so obtain a superb nugget, which he would drag around behind him on a little cart and sign it André Breton.”

Those associated with Dada were not the only ones to balk at the proposed congress; André Gide dismissed it as an attempt “to teach people how to mass-produce works of art.” But an outpouring of positive support from the public at large suggested how much latent yearning there was for the creation of a “ministry of the mind,” as one person put it.

This was, after all, a moment that has become known as a return to order in France—retour à l’ordre—with Cocteau conspicuous among those clamoring for it. It was the moment prophesied by Apollinaire, who not long before his death in 1918 had delivered a lecture called “The New Spirit and the Poets.” Advocating an “encyclopedic liberty” as the poet’s prerogative, he concluded with a nationalist peroration on France as “guardian of the whole secret of civilization,” responsible for keeping the house of poetry in order. The resonant phrase of Apollinaire’s title was adopted by Le Corbusier and Amedée Ozenfant for their journal L’Esprit Nouveau. (The first few issues were edited by Paul Dermée, a Dadaist, with the names of the Paris Dadaists listed as editorial consultants—no matter that Dermée himself was persona non grata in Breton’s circle.) This congress sounded exactly like the sort of forum L’Esprit Nouveau might sponsor, especially with Ozenfant himself as one of the organizers.

All these efforts to organize Dada or inject it into some broader schematization were wearing Picabia’s patience thin. As he sniped in the pages of 391, “Dada—it has become Parisian and Berliner wit.” After he stormed out of the Barrès trial, he fired off an article for Dermée to publish in the June 1921 L’Esprit Nouveau, venting at the conspiratorial drama consuming the Littérature circle. “I was getting terribly bored. I would have liked to live around Nero’s circus; it is impossible for me to live around a table at the Certà, the setting for Dadaist conspiracies!” He went on to claim, not altogether erroneously, that he and Duchamp had “personified” Dada as long ago as 1912, that it was subsequently given a name, and that the concept had lately been squandered by taking on the characteristics of a movement. He acknowledged leaving Dada out of both boredom and wariness that it was following in the footsteps of Cubism, gathering adherents and insiders: “I had the impression that Dada, like cubism, was going to have disciples who ‘understood.’” In L’Esprit Nouveau, he confesses, “I separated from Dada because I believe in happiness and I loathe vomiting.” Still, vomit Picabia did.

Picabia’s estrangement from the movement did not deter the public perception that his contributions to the upcoming Salon d’Automne of 1921 would be anything other than a Dada prank. It was even rumored that one was, literally, explosive, and the head of the salon had to issue a statement assuring the public of their personal safety in its presence. Picabia contributed two paintings, neither of which inflicted bodily harm upon any of the attendees. One was derived from a technical diagram. When commentators in the press objected that it was absurd to present a diagram as a painting, he responded that it was absurd to presume that copying apples was more dignified than copying a blueprint.

Picabia’s second painting has since been enshrined in the annals of Dada, even serving as the dust jacket illustration of one history of Paris Dada. Titled L’Oeil Cacodylate for the medication Picabia was taking during an attack of ocular shingles he suffered early in the year, this large canvas (fifty-seven by forty-five inches) was little more than a guest book, bearing the signatures of dozens of the artist’s friends, with whatever inscriptions they thought to add. He declared it finished when the space was filled, simple as that. He elaborated on its subject with characteristic wit: “The painter makes a choice, then he imitates his choice, the deformation of which constitutes Art; why not simply sign the choice instead of monkeying about in front of it? Enough paintings have accumulated: the approving signature of artists—only those approving—would give a new value to art works destined for modern mercantilism.” You want signatures from artists? Picabia asked, well here they are and nothing but. They included those of wife, sister-in-law, and mistress, the composers Auric, Poulenc, Milhaud (who wrote “I’ve been called Dada since 1894”), and a few of the Dadaists including Tzara, Ribemont-Dessaignes, Dermée, and the Russian Serge Charchoune. Isadora Duncan applied her signature in green above a photo of the artist’s head—a halo for the man whose Dada pedigree seemed unimpeachable.

Picabia, argonaut of the Dada sensibility from New York to Switzerland and Paris, was also an argonaut perfectly contemptuous of any golden fleece. He was in a sense a pure distillation of his generation, forged in the aphoristic cauldron of Nietzsche, whose “will to power” he took to heart as a code—not a code of “honor” but of bare life, biological ardor pursuing its moment-by-moment destiny. Much as Picabia was a wizard at scattering nuggets of philosophical contempt across the lively pages of 391, he consistently reaffirmed his Nietzschean outlook, often quoting from the philosopher without attribution. Maybe Picabia was so steeped in The Gay Science, Beyond Good and Evil, and Zarathustra he’d come to hear Nietzsche’s thoughts as his own. The spirit in which he dealt with his alienation from Dada was certainly Nietzschean in its avowal of a life spirit unhindered by the past. Nietzsche’s most biting critique was directed at what he called herd mentality, the salient characteristic of which was ressentiment (the German sage insisted on the French term). Picabia had none of that. He never felt betrayed by his friends, just bored by their tendency to behave like military officers or, as in the Barrès trial, members of the judiciary.

Although it’s hard to find extended expository prose in Picabia’s writings—he’s too slapdash, irreverent, and spirited to submit to what he’d have called a classroom obligation—he did write a response to one of the few articles in the press that took Dada seriously. Published early in 1920, “Dadaism and Psychology” by Henri-René Lenormand sufficiently engaged his attention that he replied at length in a letter unpublished during his lifetime. To the familiar charge of Dadaist behavior as “mad,” Picabia offers a retort: “One thing opposes this assertion: lunacy necessitates the obstruction or at least the alleviation of the will, and we have willpower.” Then, in a kind of personal credo, he uncharacteristically elucidates “the mechanism of our will: negative at the moment the association of ideas is formed, it becomes positive with the choice that follows.” As to Lenormand’s attempt to account for Dada in Freudian terms, Picabia does not so much disprove it as brush it aside. Dada, he says, has little to do with psychology, “it is more in physical phenomena than in any other that we must find the explanation.” It is a detoxification, he contends, and in an analogy comparable to Hugo Ball’s vision of Dadaists as babes in arms, Picabia suggests that the quest for knowledge pursued by Dada involves a regression to childhood: “Children are closer to knowledge than we are since they are closer to nothingness, and knowledge is nothing.”

This syllogistic explanation was written concurrently with a manifesto Picabia concluded with emphatic exasperation:

DADA wants nothing, nothing, nothing, it does something so that the public can say: “we understand nothing, nothing, nothing.”

“The Dadaists are nothing, nothing, nothing, they will most certainly amount to nothing, nothing, nothing.”

—Francis Picabia

Who knows nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing.

Picabia was consistent in his revulsion against art or any enterprise that laid claim to something, some tangible product or endgame that superseded the simple daily sentience of the living organism. I sniff the air, he would say, I don’t check my stock portfolios. “Life has only one form: forgetting,” he wrote in April 1920 in one of many aphorisms in his brief-lived journal Cannibale. A variant of the sentiment appeared in The Little Review: “I am for incineration, which conserves ideas and individuals in their least cumbersome form.”

A year later, after his stormy departure from the Barrès trial, Picabia’s withdrawal from Dada was taken up in the newspapers, so he tried to clarify the situation in two accounts. In Comoedia, he began by saying “I approve of all ideas, but that’s it, they alone interest me, not what hovers around them; speculations made on ideas disgust me.” This was a man who had come up with the brilliant one-liner: in order to keep your ideas clean, change them like you change your clothes. “You have to be a nomad,” he wrote, “and go through ideas the way you go through countries and cities”—speaking from considerable experience.

Perhaps owing to his painful eye infection, and exacerbated by the claims made by Walter Serner and Christian Schad that Tzara was an imposter, he assembled a special “supplement” to 391 published as Le Pilhaou-Thibaou in July 1921, a nonsense title suggesting, if anything, the Tabu Dada movement of his friends Jean Crotti and Suzanne Duchamp (Marcel’s sister). In fact, Crotti’s contribution on the front page announced himself as Tabu-Dada: “My feet have started to think and want to be taken seriously.”

The sixteen pages of Le Pilhaou-Thibaou were lavishly designed and drew more on the contributions of others than issues of 391. In addition to Crotti and Picabia himself (with his English nom de plume Funny Guy), the contributors were Paul Dermée, Jean Cocteau, Ezra Pound, Clément Pansaers, Duchamp, Georges Auric, Céline Arnauld, Guillermo de Torre, Gabrièle Buffet, and Pierre de Massot. None of them would have been considered Dadaists at that point. Dermée and Cocteau, in fact, were both on the outs with the Dadaists for their patent careerism in the avant-garde, and Arnauld, being Dermée’s wife, was guilty by association.

In the midst of this multifaceted compilation, Picabia had his usual field day. “To those talking behind my back: my ass is looking at you,” a reproach clearly aimed at his former comrades in Dada, was actually a quote from Gustave Flaubert. “I don’t need to know who I am since all of you know,” on the other hand, is closer to his usual flair for the clever barb. Such aphorisms romped in the margins next to the contributions by others. But in a longer piece Picabia squeezed out a bit more diagnostic pus: “Can’t you sense that what you call your personality is just a bad digestion that poisons you and conveys your bouts of nausea to your friends?” Is he addressing himself here, one wonders, or others?

Le Pilhaou-Thibaou proclaimed Picabia’s release from the grip of Dada. Cocteau’s contribution made it explicit:

After a long convalescence, Picabia has recovered. My congratulations. I actually saw Dada exit through his eye.

Picabia hails from the race of the contagious. He shares his illness, he doesn’t catch it from others.

Another notable contributor to Le Pilhaou-Thibaou was Ezra Pound, recently relocated to Paris after a decade in London. Early in 1921, Pound spent several months on the Riviera where he tutored himself in Dada at the bookstore of Georges Herbiet, who, under the name Christian, translated some of Pound’s work into French. A sequence titled “Moeurs Contemporaines” (in Pound’s original) appeared in Le Pilhaou-Thibaou and in the Belgian journal Ça Ira, published by Clément Pansaers, the main proponent of Dada in Belgium; an extract also appeared in the Dutch Dada journal Mécano. It’s a fierce and amusing piece of social satire, owing more to Pound’s idol Henry James than to Dada. There were other pieces by Pound written in French in a more recognizably Dadaist vein, but more important is his personal association with Picabia, which gave him a lifelong connection with an unfettered human mind. He never knew Duchamp, but Pound would have likely concurred with Breton’s observation about Picabia and Duchamp that “they move without losing sight of the major elevation point where one idea is equal to any other idea, where stupidity encompasses a certain amount of intelligence, and where emotion takes pleasure in being denied.”

Artists and writers in Paris, 1920. Kneeling, left to right, are Man Ray, Mina Loy, Tristan Tzara, and Jean Cocteau. Standing behind Cocteau is Ezra Pound.

Scala / White Images / Art Resource, New York.

In October 1921, in one of his “Paris Letter” contributions to The Dial, Pound informed American readers of Picabia’s “hyper-Socratic destructivity,” citing his Thoughts Without Language, the book that thrilled Breton. Pound was transfixed by the “very clear exteriorization of Picabia’s mental activity” in everything he undertook. “Picabia’s philosophy moves stark naked,” unencumbered by the usual scaffolding of explanation, the poet suggested. In Guide to Kulchur (1938), Pound recalled Picabia’s conversation on “a Sunday about 1921 or ’22” as “the maximum I have known.” He was a man so “intellectually dangerous,” in fact, “that it was exhilarating to talk to him as it would be exhilarating to be in a cage full of leopards.” In short: “There was never a rubber button on the tip of his foil.” Pound sensed that this was not owing to some obscure need to inflict pain or seek revenge. Picabia’s propensity was nature’s gift, the way a greyhound runs because of its breeding, or as Marianne Moore put it memorably in a poem: “an animal with claws wants to have to use / them.”

The correlation between wit and claws is longstanding, and the prospect that blood might be drawn is what distinguishes wit from just horsing around. The Dadaists gleefully took aim at themselves, but always with the assumption they were superior to the goggle-eyed bourgeoisie. Picabia, though, was different. If nobody was immune to his barbs, neither did he single out a particular group for derision. He jauntily made all sorts of false claims about people, including his friends, throughout the pages of 391—adding a dash of gossip-column spice to the stew, albeit as a sleight of hand. The closest he came to vengeance was in the folded sheet The Pine Cone, half of which was given over to Crotti’s Tabu Dada. Picabia pelted Tzara and Ribemont-Dessaignes with various insults, like “Your modesty is so great that your works and inventions will only attract flies.”

When Le Pilhaou-Thibaou was produced in July 1922, Picabia was tenuously allied with Breton’s attempt to convene his Congress on the Modern Spirit, effectively taking sides against Tzara. Eventually that too was water under the bridge; when Breton formed his new movement, Surrealism, Picabia astutely observed that it was “quite simply Dada disguised as an advertising balloon for the house of Breton & Co.” Picabia himself was always ready to move on, abiding by the zesty principle: “Our head is round to allow thoughts to change direction.”

Picabia’s maxim could count as the last word on Paris Dada, but not the final incident. That occurred on the evening of July 6, 1923, at the Théâtre Michel in Paris, when a performance of Tzara’s Le Coeur à gaz (Gas Heart) was aggressively interrupted by several young men of letters no longer calling themselves Dadaists.

The performance was part of an evening billed as the “Soirée of the Bearded Heart.” The convulsive seasons of Dada having made theatrical managers wary of renting their properties for such events, Tzara had been forced to work by subterfuge, enlisting the aid of exiled Russian writer Iliazd (Ilya Zdanevich), who had dabbled in proto-Dada-cum-Futurist performances in his homeland. Iliazd booked the hall, and an elaborate program was drawn up that was in many respects a pinnacle of the avant-garde at that moment—less Dada, perhaps, and closer to whatever the ill-fated Congress of Paris had envisioned.

The evening’s program included three films: one of Hans Richter’s abstract “rhythm” exercises and Man Ray’s Return to Reason, produced on the shortest possible notice when Tzara came up with a camera and some film. Like his rayographs coming to life, his film inaugurated yet another turn in his ever-inventive forays through different media. The third film was Manhatta, a portrait of New York by Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand. Some piano pieces by Pound’s protégé and self-declared “bad boy of music,” George Antheil, were performed, as well as a dance by Lizica Codreano. There was also a repertoire of poems, including several by former Dadaists, from whom Tzara was now utterly estranged.

Getting wind that their poems were to be used by a man—and a movement—for which they no longer felt any allegiance or affinity, the disaffected Dadaists showed up determined to disrupt the proceedings. At an innocuous reference to Picasso by Pierre de Massot, Breton (“a thick-set bully” in one account) stormed the stage and thrashed the poor fellow with his cane, breaking his arm. Police intervened and expelled Breton, but his allies remained, seething and waiting for their next opening. This came during the performance of Gas Heart, a play dating from 1920, featuring the characters Eye, Mouth, Nose, Ear, Neck, and Eyebrow. The actors were outfitted with Sonia Delaunay’s stiff trapezoidal costumes. Once the curtain rose, Paul Éluard erupted from the audience, making a stink over the expulsion of Breton and demanding that the villainous Tzara show himself. As soon as Tzara appeared, Éluard leaped onstage and punched him in the face. Stagehands and audience members came to his defense, while others joined the fray, busting up the set and leading to further expulsions.

In a sense, Éluard’s explusion was the most far flung. Within six months of the fracas at Théâtre Michel, the French poet vanished from Paris without a word to his friends, embarking on a voyage to the Far East as if carrying out literally the assignment Breton had figuratively announced in his piece “Leave Everything,” published in Littérature in April 1922:

Leave everything.

Leave Dada.

Leave your wife, leave your mistress.

Leave your hopes and fears.

Drop your kids in the middle of nowhere.

Leave the substance for the shadow.

Leave behind, if need be, your comfortable life and promising future.

Take to the highways.