When Paul Éluard abruptly left Paris on March 24, 1924, no one had a clue about his intentions or his whereabouts, although the provocative title of his new collection of poems might have given them pause: Mourir de ne pas mourir (Dying of Not Dying). For those in the know, there was an additional twist: the frontispiece was a portrait of the author by Max Ernst. The two men were deeply embroiled in a ménage à trois with Éluard’s wife, Gala, when the poet abruptly disappeared.

Éluard surmised at one point that he’d been within a kilometer of Ernst at Verdun, one of the costliest engagements of a miserable war for which neither man had any enthusiasm. Whether or not they’d been that close in the combat zone, the supposition reinforced an abiding bond between them, forged by the realization that each might have killed the other. Ernst had been conscripted three weeks after the war began, serving in an artillery unit. He was injured, although—fortunately for him—only by the recoil of a big gun and the hind leg of a donkey. Relocated to a command post, an officer recognized this young recruit as none other than the artist whose work he’d seen recently at Alfred Flechtheim’s gallery in Düsseldorf.

When the war had broken out, the twenty-three-year-old Ernst was beginning to see some success as an artist. A year earlier, in August 1913, he’d funded a monthlong trip to Paris by the sale of a painting. His first exposure to the full range of modern currents in art was at the 1912 Sonderbund exhibition in his native city, Cologne. This was the same exhibit that inspired organizers of the Armory Show in New York to rethink their plans; like them, Ernst was awestruck by this cornucopia of Fauves and Expressionists and Cubists. His plunge into the latest art was aided by August Macke, the Expressionist who lived in nearby Bonn and whose circle the young artist frequented. Through Macke he was exposed to the Blue Rider group in Munich, meeting Kandinsky during the latter’s trip to Cologne in early 1914. Ernst was also present when Robert Delaunay and Guillaume Apollinaire visited Macke on their way back to Paris from Berlin, where the French artist’s brilliantly colored paintings, deemed “Orphic” by the poet, were featured at Sturm Gallery. These encounters reinforced Ernst’s sense of mission, even as his father (an amateur painter) literally screamed at him for indulging in this grotesque tendency to splash colors all over the canvas without regard for actual appearances.

Another key encounter came in May 1914, when Ernst was strolling through an exhibit of French art in Cologne and came across a young man explaining the work to an outraged elderly gentleman. Rather than being confrontational or intemperate, the younger fellow patiently persisted “with the sweetness of a Franciscan monk and an adroitness worthy of Voltaire,” but to no avail. Afterward, Ernst introduced himself and made a lifelong friend of Hans Arp, who had been visiting his father.

That summer, Arp warily observed the escalation of international tensions and warned Ernst that things would soon take a turn for the worse. He was right, but only Arp made it out of the country to neutral Switzerland on one of the last trains before the borders were closed. The two young artists shared a dedication to the latest in modern art, which Arp took with him to Zurich, providing Dada its early profile as a successor to these tendencies.

Meanwhile, Ernst endured the war and kept abreast of what was going on in the art world as best he could. He had a reliable informant in Luise Straus, two years younger, whom he’d met in a drawing class before the war. “What I first noticed about him,” she wrote later, was his “astonishingly shining blue eyes, his extravagant colored silk ties, and his constant radiant contentment, that held something very childish at the same time as a superior irony.” Lou, as she was known, completed her doctorate in art history in 1917, by which point she and Ernst were engaged. This was not a welcome prospect for either family, traditionally Jewish on her side, traditionally Catholic on his. After their marriage in October 1918, she worked at the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne, curating an exhibition on “Depictions of War Through Graphics” in 1919, and maintained an active professional profile until the birth of their son, Jimmy, in June 1920.

Max and Lou Ernst thrived in Cologne’s lively postwar arts scene. As Lou put it, “we were the leaders of one of those groups that shot up like mushrooms then, with their lectures, concerts, meetings, but especially a lot of big ideas and little scandals.” One scandal, such as it was, involved a prearranged disruption of a vapid monarchist play, which drew the ire of local journalists who denounced the escapade as a symptom of “literary Bolshevism” and “Dadaism.” That was in March 1919, when the charge of being a Dadaist meant little to Ernst. It wasn’t until that summer, during a trip to visit Paul Klee in Munich, that he was exposed to the latest issues of Dada coming out of Zurich. Dada revealed, among other things, that his prewar friend Arp was part of the movement, whatever it was.

During this trip Ernst also encountered the haunting dreamlike paintings of Giorgio de Chirico in the Italian journal Valori Plastici. As he recalled, “I had the impression of having met something that had always been familiar to me, as when a déjà-vu phenomenon reveals to us an entire domain of our own dream world that, thanks to a sort of censorship, one has refused to see or comprehend.” He absorbed the Italian’s work not so much as a stylistic or conceptual influence but as an alternate world he could explore only by way of his own art. In years to come, the Surrealists would regard de Chirico’s work as exemplary for their movement, but where the Italian artist seemed to have abruptly turned aside from its potential, Ernst soldiered on, becoming one of the abiding standard bearers of whatever Surrealism would be in the visual arts. “As a Dadaist he was already a Surrealist,” Richter observed of Ernst, who arrived at that sweet spot even before André Breton baptized it.

But before Surrealism was inaugurated in 1924, there was Dada, and in truth Ernst was among its most stalwart standard bearers. Although he would be barred from entry to France when the Dadaists sponsored his exhibit there in 1921, Ernst finally made it to Paris the next year in clandestine and complex circumstances. And even before that, he had pioneered a Dada season in his native Cologne. His transit offers a glimpse into the wayward exhilaration Dada could provide, especially for those not living in the major Dada centers—Zurich, Berlin, Paris—but keenly attentive to reports that trickled in from those locales.

By the end of 1919, Ernst was in frequent contact with Tzara in Zurich, Schwitters in Hanover, and, less keenly, the Berlin Dadaists. He was freely adapting their attitudes and jargon, referring to some of his assemblages as “merz paintings” and generally coming around to the sense that he and a few local friends were mining the vein of Dada. These friends included Otto Freundlich, Heinrich and Angelika Hoerle, and Johannes Baargeld. The Hoerles shared an outlook close to that of the Herzfeld brothers in Berlin, for whom art was a weapon in political action. Their journal, Der Ventilator, issued in six installments in February and March 1919, was distributed at factory gates.

Ernst and his friends called themselves W/5, short for Weststupidia 5—English having local relevance, since the Rhineland was then occupied by Allied troops. If they thought of Weststupidia as Dada, it was in spirit not in name. The issue was forced in November, when an artists’ society to which they belonged held an exhibition and the organizers balked at including the work of Ernst’s group. The upshot was a parallel exhibit housed in the same venue, with a clarifying sign:

This inaugural Dada exhibition in Cologne offered a heterogeneous range of objects, prompting some of the participating artists to withdraw their works before its premiere. It was the opening salvo in what a local journalist decided was a program of “methodical madness,” wondering whether to be indignant or amused. The terms of that indecision strike a note familiar from other cities in which Dada made its mark.

One person who laughed at this latest Dada’s manifestation without laughing it off was Katherine Dreier, visiting from New York. Familiar with Duchamp, Man Ray, and Picabia, she was keenly appreciative of what Ernst and his cronies were up to and tried to arrange for the exhibition to come to America for Societé Anonyme. Unfortunately the occupying British authorities would not permit it, and as was also the case with the Berliners after the International Dada Fair, Americans never got to experience German Dada as a group effort.

The Dada initiative in Cologne was augmented by the arrival of Hans Arp for ten days in February 1920, shortly after Tzara moved to Paris. The input of Arp’s perspective from Zurich probably reinforced Ernst’s instinct about keeping his distance from Berlin. Writing to Tzara on February 17, he referred to the Berliners as “counterfeits of Dada.” He found them “truly German” in that “German intellectuals can neither shit nor piss without ideologies.” (An amusing example of that spirit comes from Vera Broïdo, one of Raoul Hausmann’s ladies. “One day as Baader and Hausmann went for a walk with a writer friend,” she relates, “the latter stopped near a tree and peed. Seeing that the others continued their walk, he got annoyed and said as he peed that the others should do the same. This is characteristic of the attitude of the Berlin Dadaists towards their art.”)

Ernst also sensed the growing ideological outlook of his Cologne colleagues, and the Hoerles would split from Dada by April, forming their own group called Stupid. “We have turned away from all individualistic anarchy,” they declared, expressing their wish “to be the voice of the people.” As a consequence, they concluded, “We reject the supposed anti-middle-class buffoonery of Dada, which only served to amuse the middle class.”

They had a point about Dada’s bourgeois roots, although the middle class was hardly amused. Its response to Dada everywhere was summed up in the title of Raoul Hausmann’s article in Der Dada 2 in February 1919, “Der deutsche Spiesser ärgert sich,” which might be translated as “The German bourgeoisie is getting worked up.” As for Ernst, his wrath was existential, not political. “A mad gruesome war had robbed us of five years of our lives,” he recalled in 1958. “Everything that had been held out to us as right, true and beautiful fell into an abyss of shame and ludicrousness. My works at the time were not supposed to please anyone; they were supposed to make people howl.” And howl they did, not only at the works themselves but at the attitude expressed in the title of Ernst’s lithograph series, Fiat Modes—Pereat Ars, or “Let there be fashion—down with art.”

“Dada Early Spring Exhibition,” Cologne’s major Dada event, came about when Ernst and Baargeld were refused access to a show being mounted at the Kunstgewerbe Museum. They countered by organizing their own exhibition. It was held in a pub, with access only through a restroom, beyond which one encountered a young girl in a communion dress reciting obscene lyrics. As reported in the press, “You go through a door in a building behind a Cologne bar and run into an old stove; to your left is a vista of stacked-up bar chairs, and to your right, the art begins.” The reporter expressed a preference for the left-hand view. On exiting the exhibition space, viewers “pass a couple of open garbage cans full of eggshells and all kinds of junk, and cannot decide whether these belong to the exhibition or are ‘natural originals.’” One of the works exhibited was a fish tank Baargeld filled with red water, a wig floating on top and a mannequin’s hand submerged in the murk.

The authorities promptly shut down the exhibit after complaints of pornographic content, but the ban was lifted the next day, when the offending item was revealed to be Albrecht Dürer’s revered Adam and Eve, which Ernst had glued into an assemblage. A poster exclaimed:

DADA TRIUMPHS!

REOPENING

OF THE EXHIBITION CLOSED BY THE POLICE

DADA IS FOR PEACE AND ORDER

The exhibit struck many as fraudulent. But the organizers rebutted: “We said quite plainly that it is a Dada exhibition. Dada has never claimed to have anything to do with art. If the public confuses the two, that is no fault of ours.” This was exactly the sort of rhetoric Ernst’s father found offensive, quite apart from his art. “I curse you. You have dishonored us,” he scornfully told his wayward son.

With its early spring exhibition in April 1920, Dada had officially arrived in Cologne. Soon, Baargeld was off on other pursuits, and Ernst’s hopes for any ongoing involvement with Dada meant setting his sights elsewhere. He’d kept abreast of the inflammatory situation developing in Paris, and in the wake of Picabia’s decisive repudiation of Tzara in Le Pilhaou-Thibaou (which Arp, too, found distressing), Ernst proposed to Tzara meeting in the Alps to lick their wounds and strategize. He thought of it as an “important conference of the potentates.” “Please decide and telegraph me,” he wrote, suggesting August 15 as a suitable date. “The immediate future of Dada depends on it.”

In the summer of 1921, Dada had little more than an “immediate” future left. It had been a year since the last hurrah at the International Dada Fair in Berlin, and even in Paris, where Dada didn’t enter the picture until Tzara’s arrival in early 1920, the movement was now spinning its wheels. To be sure, little tentacles of Dada life were slithering their way into far flung locales, from Belgrade to Tokyo, but that was Dada second or third hand—Dada as guess, wish, and innuendo. The initial fire had burned out, and even the sparks were dwindling.

So it was an inspired guess on Ernst’s part to take Dada back to its original Alpine heights—and during the traditional vacation season, no less. Dada on vacation? Odd. But this was getting near the end, and even the participants couldn’t help but sense it. For Ernst, though, it felt like his true vocation was just coming into focus. He needed to keep Dada going to keep himself going, because the discoveries he was making in his art had no foreseeable life outside the singular incubator of Dada.

Max Ernst’s objets d’art, indeed, were the quintessential “objets dad’art” (a punning title he provided). Dadamax, as he called himself, repopulated the visible world with mechanisms and automata gleaned from nineteenth-century illustrated catalogues. The cover illustration Ernst would make for a 1922 collection of poems by Paul Éluard epitomizes his Dada sensibility, insinuating itself through the viewer’s eye as an uncanny physical discomfort. As if the image of a needle being threaded through a cornea isn’t disturbing enough, the book’s title prolongs the distress: Répetitions. (Characteristically, even this vivid motif was derived from a prior source, his fellow Dadaist Johannes Baargeld’s The Human Eye and a Fish, the Latter Petrified, which hung in Ernst’s living room.) Despite his obvious and growing affinity for the movement, however, Ernst was fated to have clambered onboard the Dada raft at the very moment it started to sink—a coincidence that led him to seek refuge in the unlikeliest of places.

Vacation in the Tyrol offered the immediate gratification for Ernst of spending precious time with Arp, as well as the opportunity at long last to meet Tzara. And of course Lou and little Jimmy would thrive in the mountain air. It was a happy occasion all around, overflowing into postcards they sent friends and comrades. As enticement to Paul Éluard: “Max Ernst is giving each Dada who comes to Tarrenz a picture. He is here with his wife and his baby Jimmy, the smallest Dadaist in the world.”

Éluard couldn’t make it to the Tyrol this time around, but there was a palpable appeal in the idea of a retreat with the German artist. Ernst’s show at Au Sans Pareil had been held in May, and with Picabia’s apparent defection from Dada, Ernst was the great hope of the movement. (Man Ray had only just arrived in Paris, and his own exhibit wouldn’t be until December.)

In any event, it was not Éluard but Breton and his new bride who arrived near the end of the vacation. Ernst immediately felt the aura of grandeur that hung about the man like a cape, an “almost magical presence,” it seemed, marked by “presumptuous politeness, and a frank, uninhibited authority.” He also discerned the discomfort of Tzara and Breton in each other’s company.

By the time the Bretons arrived, the trio of Arp, Tzara, and Ernst had produced a small publication regarded as the final issue of Dada. Its title (suggested by Tzara’s girlfriend from Zurich, dancer Maja Kruscek) was the slaphappy-sounding Dada in Tyrol the Singers’ War Outdoors (Dada Intirol augrandair der Sängerkrieg), and although it retained the high spirits of the vacation—most of the writing was in a gleefully nonsensical vein—it made a point of responding to the poisonous claim Picabia made in Le Pilhaou-Thibaou that Dada was created by himself with Duchamp and that Tzara had, at most, found the word—though even that attribution was in question, with Huelsenbeck listed as cofounder. In Dada Intirol, Hans Arp contributed a send-up of this vexing issue of paternity, which has nevertheless influenced the collective memory of how Dada evolved.

I declare that Tristan Tzara found the word DADA on 8 February 1916 at 6 in the evening; I was present with my 12 children when Tzara pronounced for the first time this word that unleashed in us a legitimate enthusiasm. This occurred at the Café Terasse in Zurich and I bore a brioche in my left nostril. I am convinced that this word has no importance, and that only imbeciles and Spanish professors are interested in dates. What interests us is the dada spirit and we were all dada before the existence of dada.

The prehistory of Dada was mockingly suggested in the date the periodical bore: September 16, 1886–1921. This was in fact Arp’s birthday, extended to the present moment, his thirty-fifth year.

The first item in the publication, signed by Tzara: “A friend from New York tells us about a literary pickpocket; his name is Funiguy, celebrated moralist.” Funny Guy was the nom de plume with which Picabia signed many of his freewheeling writings in 391. In a separate note, Tzara extended the lampoon, informing the reader that Funny Guy invented Dadaism in 1899, Cubism in 1870, Futurism in 1867, and Impressionism in 1856—the year of Freud’s birth, although Tzara may not have known or intended that coincidence.

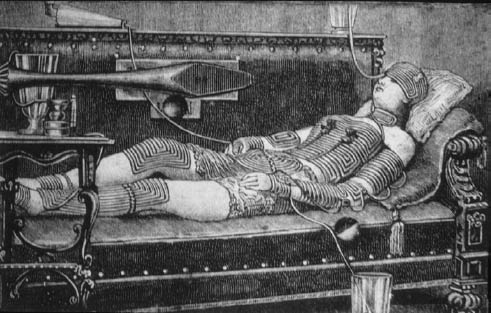

Dada Intirol included only two visual works, a woodcut by Arp and a collage by Ernst, the latter taking pride of place under the journal’s title (printed upside down and backward). It was named The Preparation of Glue from Bones, and it is a splendid example of the lugubrious world Ernst could summon almost casually, his finger on the pulse of an otherworldly arterial network pumping dreams instead of blood. Werner Spies characterizes it as a “collage manifesto,” inasmuch as the title alludes to the procedure of making collages. Ernst added very little to an image already sufficiently arresting, an illustration from a medical journal depicting diathermy treatment. (A photograph of the treatment can be found in Foto-Auge or Photo-Eye, assembled by Franz Roh and Jan Tschichold in 1929, where it’s intriguingly juxtaposed with Georg Grosz’s collage-painting The Monteur Heartfield.) Ernst was so taken with the image he replicated it in a large painting. With its bright colors, it “naturally has a much insaner effect than the little reproduction.” It was destroyed during the Second World War, but its impact persists in a photograph of Düsseldorf gallery owner Mutter Ey and a group of enthusiasts posing with the painting like a sacred talisman of some obscure religion.

Max Ernst, Preparation of Glue from Bones, published in Dada Intirol (September 1921).

Copyright © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Because he couldn’t extricate himself from professional obligations in Paris in time to meet Ernst in the mountains, Éluard arranged for a visit to Cologne where he and Gala spent a week in early November. They took in a Man Ray exhibit Ernst arranged, as well as a separate exhibition of Ernst’s own work. The stimulating visit resurrected the bright spirits that had animated the Tyrolean vacation. The mood continued when Tzara arrived in December for three weeks. But the Éluards’ Cologne visit proved to be stimulating in unexpected ways as well.

During that week, Ernst and Gala Éluard felt the first pangs of a mutual attraction. Gala was Russian, born Helena Dimitrievna Diakonova in 1895, the same year as Éluard. Gala and Éluard met at a sanatorium in Switzerland when they were both seventeen, developing a bond that lasted after they returned to their homelands. Finally, in 1916, Gala came to Paris where she lived with Éluard’s parents while he was serving at the front, and the young couple married during a short leave he’d obtained in February 1917. It was a point of contention between them when, in December, Éluard abandoned his post as a medical orderly and enlisted in an infantry unit, needlessly risking his life in combat. He survived, and the couple had a daughter, Cécile, in 1918.

As soon as they met in Cologne, Ernst and Éluard regarded each other as long lost soul mates, thanks to their recent proximity in combat, and when the Éluards returned to Paris, the two men embarked on a collaboration by post, the fruit of which was published in March under the title Répétitions, with poems by Éluard and collages by Ernst. As soon as the book came off the press, Éluard and Gala headed back to Cologne with fresh copies, high spirits—and aroused senses.

The rapport between Ernst and Gala that developed in November precipitously came to a head. In her memoir, written twenty years later, Lou still seethed at the indignity of what transpired and at the woman to blame for it: “This slippery, scintillating creature with cascading black hair, luminous and vaguely oriental black eyes, delicate bones, who, not having succeeded in drawing her husband into an affair with me in order to appropriate Ernst for herself, finally decided to keep both men, with the loving consent of Eluard.”

The impetuousness of the affair between Gala and Ernst was even more striking because her daughter and his son were on hand. It made for one big unhappy family. There are several group portraits of the four adults and two children, and it’s hard not to register Lou’s bewilderment, Gala’s intensity, Ernst’s fixation. And Éluard? As Tzara divulged, “Eluard liked group sex. He was keen for his friends to make love to Gala—while he watched or joined in.” And the friend in this case was more like a second self. During this time, Ernst executed a double portrait in which his head and Éluard’s blend into a single entity, exactly like the collages Raoul Hausmann produced in Berlin, merging his head with that of Baader, the Oberdada.

The appeal of Dada in the Alps held over from 1921 into the next year, when the original vacationers were joined by the Éluards, along with American writer Mathew Josephson and his wife, Hannah. Josephson was living in Paris, where he’d met Tzara through Man Ray, and at Man Ray’s exhibit at Au Sans Pareil in December, he’d struck up a rapport with Louis Aragon. Soon he was attending all the Dada events, hanging out at Café Certa and the other watering holes frequented by the Littérature clan. “While there were certain inconveniences in such a group life,” he found, “one felt there was a warm spirit of comradeship ruling them. Whereas, in contrast, a gathering of avant-garde American writers and painters would have found everyone talking at cross-purposes.”

Reunited in the Alpine setting, Tzara and Arp anticipated a reprise of the previous year’s Dada publication, but such hopes were dashed by the grim mood surrounding the ménage à trois. Even the participants seemed none too happy about the affair. It was a pressure cooker with Ernst, Éluard, and Gala occupying one room, while Lou and little Jimmy were next door (the Éluard daughter was with her grandparents, back in Paris). “You’ve got no idea what it’s like to be married to a Russian!” Éluard exclaimed to Josephson, who felt that while Ernst “carried himself with much aplomb in a difficult situation,” Gala’s “changeable moods” and nervous tension poisoned the atmosphere. “Of course we don’t give a damn what they do, or who sleeps with whom,” lamented Tzara. “But why must that Gala Éluard make it such a Dostoyevsky drama! It’s boring, it’s insufferable, unheard of!”

The only relief, in Josephson’s view, came with the arrival of Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber. The American found Arp to be “one of the most lovable and fantastically comic companions I have ever had,” able in a wink to go from monkish sobriety to Mack Sennett movie clown. Arp’s oblique way of acknowledging the extra- and intramarital escapade unfolding was to declare, “I could never make love to a woman unless I were married to her”—his own conspicuously intimate, longstanding relationship with Sophie notwithstanding. (The couple would finally marry later that year.)

There would be little point in mentioning the ruckus surrounding the Max-Gala-Paul triangle but for its precipitous outcome. Had it been confined to a week or two here and there, in Cologne and in the Alps, it would have receded to little more than a biographical detail in three lives better known for other things. (Gala, for instance, went on to marry Salvador Dalí.) But the tryst was not fleeting. One day Lou reproached her husband for being verbally abusive toward Gala, wondering why she put up with it, because Lou herself surely wouldn’t. Ernst coldly turned to her and said, like a slap in the face, “I never loved you as passionately as I love her.”

Ernst resolved to follow the absorbing couple to Paris for a few weeks, but Lou told him not to return. The problem for Ernst was that he had no legal way to enter France. In a solution that added another complication, Éluard let Ernst use his own passport. Consequently, Ernst became an illegal alien, without means. Once in Paris, he took on yet another false name (Jean Paris, of all things) just to scrape by, doing odd jobs, including being an extra for a film production of The Three Musketeers. At first his visit to Paris proved something of a romp—but before long it would contribute irrevocably to the dissolution of the movement he had avidly embraced back in Cologne.

For a time immediately following his arrival in Paris, Ernst lived with the Éluards, which meant living well, since Éluard was the only child of a wealthy real estate developer, and Éluard himself (though not to his liking) worked in the family business. The living arrangement was eyed with suspicion by Éluard’s parents—not that they knew of the sexual arrangements, necessarily, but they certainly regarded Ernst as a foreign sponger, benefitting unreasonably from the generosity of their son. As the situation wore on, the son showed signs of stress.

Before long, the spark that had made the vacation trysts so lively was emitting more smoke than fire. As early as August 1922, Dada friends visiting the suburban Éluard domicile were alarmed by the mood. One wrote to Tzara about a dinner where “the drunkenness of Éluard became dreadful.” Everyone else was jolly and in high spirits “except Ernst, who had hardly said a word during the evening, and who looked at Éluard, mouth set, eyes like those of marble statues”—exactly as he’d looked at Lou, in fact, just a month earlier in the Alps.

Somehow this eccentric arrangement persisted through the year and into the next, when in April 1923 Éluard bought a sizeable house about twelve miles outside Paris. Over the next six months, Ernst painted decorative murals all over the house. Cécile Éluard later recalled her childhood home in less than fond terms.

The exterior of the house was very banal. But the inside was fantastic and strange. All the rooms were filled with surrealist paintings, even in my room, my parents’ bedroom, the salon. Everywhere. Some of these paintings made me frightened. In the dining room, for example, there was a naked woman with her entrails showing in very vivid colors. I was eight at the time, and those images made me very, very afraid.

The innocent reference to the parents’ bedroom is striking, because as Gala later confided to a friend, Ernst and Éluard were both sleeping in her bed every night.

The situation unraveled completely soon thereafter, adding its own seismic jolts to an already deteriorating Dada scene. When the other Dadaists (as Dada was sputtering out) finally saw the Éluard place, Breton was aghast, saying it “surpasses in horror anything one could imagine.” Less than six months later, Éluard stunned everyone by slipping off suddenly, without warning or explanation. Three days after that, Breton’s wife, Simone, observed, “André’s so sad, worried, nostalgic and more detached than ever.” Two weeks later, Breton conceded that the event confirmed his “gloomiest concerns,” to the extent that “I can barely make sense of anything.” He felt even more deeply implicated by Éluard’s dedication in the book he left behind: “To simplify everything this my last book is dedicated to André Breton.” While dernier livre (last book) could innocently mean most recent, it was hard not to hear a grim finality in the wake of the man’s disappearance.

In fact, the whole group was shaken. It was as if the mock epitaph to Éluard published by Philippe Soupault back in 1920 had been an unwitting forecast of what had now come to pass: “You left without saying goodbye.” In his author’s note to this collection of “Epitaphs” published in Littérature—nine poems bearing the names of nine Dada friends—the poet confides that, feeling his verse becoming lifeless, he’d adopted this strategy, and “in reality each of the characters bearing these famous names are Philippe Soupault.” Now in the wake of Éluard’s disappearance, the notion of an epitaph loomed as something more than literary stratagem. This was in the wake of the legendary “sleeping fits,” those somnambular exercises in automatic writing that captivated but so disturbed the participants that Breton shut them down after a few weeks. The most clairvoyant participant had been Robert Desnos (who even claimed to channel messages from Duchamp’s Rrose Sélavy!), who came up with the idea that Éluard was in the Pacific. Éluard never communicated with any of his friends during his absence, but he had sought Desnos’ help in procuring a false passport, perhaps tipping his friend to a possible voyage.

So what happened to Éluard? Undoubtedly the domestic triangle proved untenable, but there are no details of what transpired in private. What’s available, instead, is a revealing missive Éluard sent his father.

24 March 1924. Dear Father, I’ve had enough. I’m going travelling. Take back the business you’ve set up for me. But I’m taking the money I’ve got, namely 17.000 francs. Don’t call the cops, state or private. I’ll see to the first one I spot. And that won’t do your reputation any good. Here’s what to say; tell everyone the same thing; I had a haemorrhage when I got to Paris, that I’m now in hospital and then say I’ve gone to a clinic in Switzerland. Take great care of Gala and Cécile.

I’ve had enough says enough. Éluard’s letter makes no mention of Ernst, but of course he was persona non grata where Éluard’s parents were concerned. And they grew even more concerned to find their granddaughter still housed with Gala and her paramour. There were rows. But it’s not as if Éluard himself was off the hook: his cavalier reference to 17,000 francs—close to $30,000 today—glosses over the fact that he’d pilfered it from family business funds.

Éluard needed the money, though, for he was on his way to Indochina, on a passenger ship recently converted from its military mission, having served as a German raider in the South Pacific. He was soon in touch with Gala, arranging for her to auction off his art collection to repay the stolen funds and generate enough extra for her to join him in the Far East. And Ernst? In the end he sailed with Gala, eventually meeting up with Éluard in Saigon, where existing photographs disclose no longer a trio but the original Franco-Russian couple in one picture and the German artist alone in another, dressed in tropical white from head to toe, gleaming so brightly he looks on the verge of being whited out altogether. Éluard and Gala left Ernst behind, and he went on to Cambodia, visiting Angkor Wat and other ruined temples that left a lifelong imprint on his art.

When Éluard returned with Gala to Paris six months after his departure, his reappearance was as chilling to his friends as his original disappearance. He slipped back into his chair at the café as if he’d just gone out for a smoke. The most he allowed was that it was an idiotic trip. “It’s him, no doubt about it,” Breton wrote despondently to a friend. “On holiday, that’s all.” The French writer Pierre Naville, on the other hand, realized it was more momentous. Éluard’s “disappearing act” he thought more significant than the train trip that brought Tzara to Paris in 1920: “Dada arrived by train and disappeared into Oceania by steamer.”

For Naville, too young to have participated in the Dada seasons in Paris, soon to be active in the Surrealist movement, Oceania signified nothing less than the profound depths of the unconscious. Tzara had rejoiced at the way Dada convulsively released “pure unconsciousness” in its Swiss audience, yet dismissed the Tyrolean ménage à trois as little more than a Slavic emotional tempest boiling over to the inconvenience of fellow vacationers. But given the avidity and desperation with which the Paul-Gala-Max juggernaut went on for years, only some deep unconscious surge could sustain it.

Ernst moved into a flat by himself and left Éluard and Gala on their own, yet he continued collaborating with Éluard. The two men remained collaboratively and personally bound to one another, confirming the double portrait Ernst had sketched soon after they first met.

There would be rocky moments, inevitably. When another of their books, Au Défaut du Silence, was published in 1925, Ernst penned this personal dedication:

Please forgive me. I love

you more than anything and more than ever.

I can’t understand what’s happening to me . . .

Ernst eventually divorced Lou and married a Frenchwoman, Marie-Berthe Aurenche. At a dinner at Breton’s in 1927 she made an impertinent reference to Gala, then on a trip back to Russia to see her family after many years away. That got Éluard going, and emotions escalated until Ernst punched him, with Éluard flailing back inconsequentially. Éluard wrote to Gala: “He dared what no one else has dared to do, hit me—and with impunity,” adding definitively “I shall not see Max again. EVER.” Within two years, however, they were pals once more, Éluard buying paintings from Ernst.

In the thirties after Gala left him for Dalí and Éluard remarried, the Ernst and Éluard couples were great companions. Not that Éluard could ever shake himself free of Gala. The evening before his wedding in 1934, he wrote her, revealing that he owed all the delights of his life to her: “None of this is possible without the reassurance of seeing you, of your voice. I need your nakedness for the desire to see others.” He kept writing to Gala in these terms to the end of his days. She always remained the libidinal spark of his life, poetic and apparently sexual as well.

By all accounts Gala was a sexual and emotional predator. Ernst’s later wife, artist Dorothea Tanning, wrote of her “burning cigarette eyes”—a perfect complement to Lou Ernst’s evocation of that “slithery, scintillating creature.” Ernst painted her inscrutable gaze in 1924, but instead of a forehead a scroll rises up from her eyes, suggesting some sphinx-like script in place of a mind.

A final glimpse of the Russian temptress comes from Jimmy Ernst, who ended up in New York (along with his father) as a refugee during World War II. Ernst the younger encountered Gala at a gallery and introduced himself as Ernst’s son, the world’s smallest Dadaist from the Tyrolean vacations. Gala lit up with convulsive interest, and he instantly smelled a rat. “The impression of a predatory feline was a strong one,” he wrote in his autobiography. “This was an unchaste Diana of the Hunt after the kill, a face and body forbidding, detached, yet in constant wait for unnamed sensualities.” Encountering nineteen-year-old Jimmy Ernst was an opportunity she couldn’t resist: having had the father, to have the son as well. It was a proposition he intuitively knew to refuse. “It was probably fear rather than resentment that told me how to respond to the invitation,” he reflected, discovering later that various people in the New York art world were betting on Gala’s odds.

By the time his former lover tried to bed down with his son, Max Ernst’s long and storied artistic career was at high noon, and he continued his unstoppable creative flowering to the end of his long life in 1976. He, like Man Ray, pioneered a psycho-aesthetic idiom in which what’s visible in the artwork extends a secret handshake to what’s invisible in the mind. For a while, in Paris anyway, it was called Dada before it transformed into Surrealism.

In the short note Breton penned for Ernst’s first Paris exhibit under the auspices of Dada, he characterized the movement in these terms: “It is the marvelous faculty of attaining two widely separated realities without departing from the realm of our experience, of bringing them together and drawing a spark from their contact.” More than three years later he reprised the formula in the first “Manifesto of Surrealism,” after crediting its source in Pierre Reverdy’s definition of the poetic image:

The image is a pure creation of the mind.

It cannot be born from a comparison, but from a juxtaposition of two more or less distant realities.

The more the relationship between the two juxtaposed realities is distant and true, the stronger the image will be—the greater its emotional power and poetic reality.

Reverdy published this in extralarge type on the first page of his journal Nord-Sud in March 1918. The same issue concludes with a poem by Tzara. A few months later Reverdy suggested that Dada merge with Nord-Sud, but Tzara politely declined.

When Breton quoted Reverdy on behalf of Surrealism, he was leapfrogging over Dada. He didn’t mention that he’d previously defined it with reference to this model of the image as a juxtaposition of distinct realities. He even fudged the date, acknowledging that the term Surrealism derived from Apollinaire, “who had just died.” That was more than a year before Tzara came to Paris, an arrival breathlessly anticipated by Breton and his friends who, needless to say, were far from calling themselves Surrealists, keen instead to join the Dada movement.

So why would Breton play fast and loose with chronology? Simply put, Surrealism was his baby as Dada could never be. In 1922, with Paris Dada on the rocks, but two years before the Surrealist manifesto, Breton wrote, “Never let it be said that Dadaism served any purpose other than to keep us in a state of perfect readiness, from which we now head clear-mindedly toward that which beckons us.” It didn’t have a name yet, despite the misleading chronology he would provide in the manifesto, but there’s no doubt it would rival Dada.

For Breton, Surrealism was everything Dada promised but couldn’t live up to. He ran the show with the steely tenacity familiar from the Barrès trial and the Congress of Paris, earning the dubious nickname “Pope of Surrealism.” But following his pledge of faith in the image, it’s clear that he needed Tzara and Dada far more than they needed him.

Surrealism as convened by Breton in 1924 consisted almost entirely of former Dadaists. Although he regarded Surrealism at first as a literary movement, the contributions of Max Ernst and Man Ray were so indispensible that other artists soon rallied to the cause, like the Spaniards Joan Miró and Salvador Dalí. That’s another story, as Surrealism outlived Dada by many decades and fitfully smolders on even today. But for Breton’s durable mansion of the marvelous, Dada was the one and only foundation, and like a foundation, out of sight underground, it did its work in the dark.