As Dada spiraled outward from Zurich in 1916, with a shadow version running parallel in New York, lighting up flashpoints from Berlin to Paris 1920–1921, it never had the consistency of a movement like Futurism. Deliberate strategies of obfuscation and contradiction—different from site to site—prevented any clear appraisal of Dada. Ambiguity prevailed.

The Dadaists themselves were inconsistent practitioners of their own ism. Someone like Duchamp never even claimed to be a Dadaist, while Schwitters’ rival enterprise, Merz, was widely thought of as Dada. The so-called Club Dada in Berlin was a loose affiliation, launching a series of public events while leaving its members free to pursue their own divergent goals, ranging from the monomania of Baader to the political commitment of the Herzfeld brothers and Grosz. Only in Paris was there an attempt to forge a disciplined collective out of Dada, but such an enterprise flew in the face of Dada anarchy and proved unsustainable.

Dada spread of its own accord, more of an artistic virus than an ideology. The “virgin microbe” pursued its infectious course, rousing scores of individuals with its feverish animation, inspiring fitful bursts of collective activity here and there. Most of the individuals touched by it were forever grateful for the stimulation but had no personal investment in Dada; only a few (Huelsenbeck and Tzara, mainly) had any proprietary stake in the origin and evolution of the phenomenon.

Hans Richter’s path from Zurich to Berlin is symptomatic of the course followed by a number of Dadaists after the war. Through much of the Dada period he was still caught up in the Expressionist turbulence, which is evident in his series of “visionary portraits” of friends like Emmy Hennings, whose book Gefängnis (Prison) he illustrated. A crucial encounter in 1918 with eminent pianist and composer Ferruccio Busoni in Zurich turned his aspirations in a different direction, however, and set him down a path that would both define his legacy and add another dimension to Dada.

Busoni favored a new aesthetic in music, one that would surmount the tempered scale of the keyboard and explore the radiant world of microtones and other sounds resisting conventional notation. This is not to say he embraced the noise machines of fellow Italian Luigi Russolo, whose Futurist manifesto The Art of Noises was published in 1913; as a world-renowned concert pianist, Busoni would hardly have agreed with Russolo’s characterization of concert halls as “hospitals of anemic sounds.” But he did share Russolo’s conviction that “our hearing has already been educated by modern life.” Take a walk around the modern city, Busoni suggested, and you’ll find yourself caught up in a medley of sounds—liquids eddying through pipes and drains, the whoosh of gas through vents, the metallic grind of trolley wheels on streetcar tracks. “We enjoy creating mental orchestrations of the crashing down of metal shop blinds, slamming doors, the hubbub and shuffling of crowds,” and all the other sounds of the humming metropolis. Busoni understood the need to organize random sounds into intelligible units, but he recognized another musical principle of organization—counterpoint. Busoni recommended to Richter that he apply counterpoint to his painting. Serendipitously, Tzara introduced Richter to Swedish artist Viking Eggeling. The two men hit it off right away, since they were both intent on finding an alphabet of visible form.

For Richter, the quest for a primal language was part of a broader effort to renew society. He was a cofounder of the artists’ group Das Neue Leben (The New Life) in Zurich, which included Eggeling as well as fellow Dadaists Arp, Taeuber, and Janco. In time, this group would come to be regarded as the European vanguard of the nascent international postwar artistic and architectural initiative known as Constructivism.

In some ways, Dada was a precondition of Constructivism and even served as a fitful ingredient. But that depended on the circumstance, since Constructivism came with conspicuous political affiliations that parsed differently from nation to nation. It may have been international, but it was nationally induced. In Germany, where Expressionism still prevailed, Constructivism was a reaction against “the formlessness and anarchy of subjectivism,” wrote one critic in 1924. It offered a platform for those who wanted “to put an end to all romantic feeling and vagueness of expression.” Even Tzara’s apparent nihilism sounded serviceable when he urged, “there is great destructive, negative work to be done. To sweep, to clean.”

As George Grosz wrote in the Constructivist periodical G

![]() , “Dadaism was no ideological movement but an organic product that came into existence as a reaction against the cloud-cuckoo-land tendencies of so-called sacred art.” A hallmark of the Dadaist outlook was knocking art off its pedestal, as in Zurich where Arp and Taeuber sought to close the gap between so-called fine art and the applied arts. As Arp put it in the Dada Almanac (writing under the pseudonym Alexander Partens):

, “Dadaism was no ideological movement but an organic product that came into existence as a reaction against the cloud-cuckoo-land tendencies of so-called sacred art.” A hallmark of the Dadaist outlook was knocking art off its pedestal, as in Zurich where Arp and Taeuber sought to close the gap between so-called fine art and the applied arts. As Arp put it in the Dada Almanac (writing under the pseudonym Alexander Partens):

In principle no difference was made between painting and ironing handkerchiefs. Painting was treated as a functional task and the good painter was recognized, for instance, by the fact that he ordered his works from a carpenter, giving his specifications on the phone. It was no longer a question of things which are intended to be seen, but rather how they could become of direct functional use to people.

Placing an order for an artwork over the telephone was something for which Hungarian Constructivist László Moholy-Nagy would later be famous. Ordering art by phone might seem a characteristic gesture of Dada iconoclasm, but in Moholy-Nagy’s case, it reflected his embrace of technological expedience.

The germination of Constructivism was more or less simultaneous with Dada. The journal De Stijl was launched in Holland in 1917 while Dada was in its second season in Zurich. It was followed by the Parisian journal L’Esprit Nouveau in 1919, when Berlin Dada was hitting its stride. Although L’Esprit Nouveau is mainly associated with architect Le Corbusier (whose contributions to the journal were collected in several highly influential books), its first issues were edited by Paul Dermée, erstwhile Dadaist. Both these journals were devoted to cleansing the Augean stables of contemporary disorder in society and the arts. Allied publications sprouted up all over Europe, many of them indiscriminately mixing Dada and Constructivist contributions, like the Hungarian exile journal Ma (Today), Schwitters’ Merz, and Mécano issued by De Stijl editor Theo van Doesburg under his Dadaist alter ego, I. K. Bonset. At van Doesburg’s urging, Hans Richter started up a major Constructivist journal, G

![]() , the G standing for Gestaltung, meaning “form/formation,” and the square serving as Richter’s homage to El Lissitzky, coeditor with writer Ilya Ehrenburg, of another influential Constructivist journal, the trilingual Veshch/Objet/Gegenstand.

, the G standing for Gestaltung, meaning “form/formation,” and the square serving as Richter’s homage to El Lissitzky, coeditor with writer Ilya Ehrenburg, of another influential Constructivist journal, the trilingual Veshch/Objet/Gegenstand.

Dada, born of the Great War, still had something to contribute to the postwar cleansing represented by Constructivism. Rebuilding a damaged world was never going to be easy, especially when powerful political forces were brewing—like the National Socialists in Germany—determined to turn back the clock to some putative golden age. Constructivism meant looking forward, not back, and found a suitable ally in Dada’s contempt for the old pieties.

Richter’s turn to Constructivism—signaled by his encounter with Ferruccio Busoni and his involvement with Das Neue Leben—took place as Germany collapsed after the war ended in November. Richter went back to Berlin, involved in founding another artists’ collective, the Novembergruppe, then returned to Zurich where he cofounded an Association of Radical Artists (in effect a change of name, since the participants were the same as those in The New Life). He participated in the culminating Dada soirée at the Kaufleuten on April 9, reading his manifesto “Against Without For Dada,” then went to Munich to participate in the recently established Communist government. He was even appointed chairman of an arts committee, but the Bavarian Freikorps smashed the revolution and Richter was imprisoned for several weeks before family connections led to his release.

It was only natural that Richter would end up in Berlin, where the force of Dada as a political weapon was being forged. But rather than joining Club Dada, he settled on his family’s estate nearby, where Eggeling joined him and the two embarked on their exploration of visual counterpoint as the basis for a universal language.

The Berlin Dadaists, scornful of art as fetish, spoke of their creative productions as if they were industrial products. At the International Dada Fair in 1920, Heartfield and Grosz brandished a placard with the slogan “Art is dead. What’s alive is the new machine art of Tatlin.” They knew little about Russian artist Vladimir Tatlin, who in fact had attempted little in the way of anything resembling machine art. But Tatlin had demonstrably weaned himself from easel painting and started producing multimedia reliefs, inspired by a visit to Picasso’s studio before the war. Tatlin favored raw materials, unrefined bits of metal and wood, anticipating Schwitters’ Merz; and it was this penchant for disavowing the putatively noble materials of the fine arts that made such work seem vaguely endowed with a Dada spirit.

By the time the newly convened Soviet Union conscripted artists for official duty around 1920, Tatlin was widely admired for having already left “art” behind. When the Dada Fair was held in Berlin, Tatlin was in Petersburg working on his Monument to the Third International, a work that rivals the fame of Duchamp’s Fountain. Duchamp’s urinal disappeared soon after it was unveiled, and Tatlin’s was a model for a monument never built. “It’s somehow strange to build a monument to something still alive and developing,” Victor Shklovsky, Russian literary critic and writer, couldn’t help but notice, though he saluted this project “made of iron, glass and revolution.” Tatlin’s tower emerged from his professional duties, which included replacing old Czarist monuments with Bolshevik ones. As head of the visual arts department of Narkompros (Commissariat for People’s Enlightenment), and on the strength of his legacy as an artist going back before the revolution and even the war, Tatlin was at the center of debates about the role art would play in the new Soviet society.

These debates about Soviet art eventually filtered into the West under the general rubric of Constructivism, but in the USSR it wasn’t quite that simple. For one thing, Constructivism was under way before the state got involved. In the annals of Constructivism, “The Realistic Manifesto” is identified as the seminal text. Written by sculptor Naum Gabo and his brother Antoine Pevsner, the manifesto was posted all over Moscow by the brothers on August 5, 1920, in coordination with an outdoors exhibit of their “constructions”—a word that better describes their work than the old term sculpture. In fact, the manifesto made no mention of Constructivism. It was, instead, a euphoric embrace of “new forms of life, already born and active,” which any bypassing Muscovite that late summer day would assume meant the USSR. “Space and time are re-born to us today,” the manifesto proclaims in a utopian but nonpartisan way. After a series of swipes against the art academies, Gabo and Pevsner conclude with a pledge:

Today is the deed.

We will account for it tomorrow.

The past we are leaving behind as carrion.

The future we leave to the fortune-tellers.

We take the present day.

This dedication has much in common with the pledges of the Dadaists, although its authors might not have thought so (nor were they even aware of Dada’s existence). In any event, the two artists did not linger long in their homeland. Gabo moved to Berlin in 1922 and Pevsner to Paris in 1923. Both had long and stellar careers as exponents of Constructivism in the West.

An earlier portent of Constructivism in the USSR occurred when a group of art students decorated Moscow streets for the revolutionary May Day festival in 1918. The experience revealed to the students an arena beyond the easel, opening onto the environment at large, and an art commensurate with the revolution, far removed from the artwork nourished by the refined taste of the old Czarist Academy of Art. The students formed Obmokhu (Society of Young Artists), holding annual exhibitions. Their 1921 exhibit proved influential outside Russia with its display of work by Alexander Rodchenko. Photographs reveal an exhibition space resembling a workshop, the floor covered with cantilevered objects, like easels and music stands cavorting in a space age quadrille. It takes close scrutiny to realize that, yes, there were also a few canvases on the walls. But where Tatlin’s explorations concerned materials, Rodchenko was interested in space. His constructions resemble prototypes for something yet to be manufactured.

Constructivism had emerged, in a sense, in opposition to the movement represented by the Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky, who was chosen to organize the Institute of Artistic Culture (INKhUK) in Moscow, a state-funded research center for the arts. He also taught at the Higher Art-Technical Studios (Vkhutemas), the industry-oriented school often compared to the Bauhaus. Kandinsky had thrived in the Munich art scene before the war, but was forced to leave Germany when the war broke out, and had been living in Moscow for the past six years. The artists he found to staff the institute had cut their artistic eyeteeth as members of the Russian avant-garde before the war. Yet early in his tenure, a countertrend was under way by artists objecting to his psychological-spiritual orientation. Kandinsky was always in search of synesthetic wonders, a kind of cross-dressing between different senses and different arts. His own awakening to art, after all, was courtesy of Wagner’s opera Logengrin, an inaugural encounter he elevated into an archetype of artistic interanimation. So he was polling members of INKhUK on questions like which color resembled the mooing of a cow or the soughing of wind in the pines and whether a given color had a natural affinity for a particular geometric form—questions some saw as irrelevant to the needs of an infant nation.

Little more than a year after organizing INKhUK Kandinsky was gone, back to Germany where he joined the faculty of the Bauhaus in June 1922. Those who had opposed his outlook, meanwhile, organized themselves into a working group of Constructivists in early 1921: Rodchenko, his partner Varvara Stepanova, Liubov Popova, Alexander Vesnin, and others. “Constructivist life is the art of the future,” declared Rodchenko in one of his teaching slogans.

The Constructivists said a formal farewell to easel art altogether. Instead of art, they executed laboratory experiments on conceptual and material problems. On behalf of the new society, these Constructivists were willing to abandon the tainted individualism of art, devoting their skills to the productive realization of “a new material organism.” “It is time that art entered into life in an organized fashion,” Rodchenko insisted, intent on exterminating any lingering decadent indulgence in art as aristocratic prerogative (“Down with art as a beautiful patch on the squalid life of the rich”). With aristocratic art expunged, artistic talent was presumed to seamlessly infuse the body politic with new health.

As the Constructivist ethos spread throughout Europe, this utopian prospect—that art might be a collective mode of social progress—took on the characteristics of a secret handshake. Constructivists pledged themselves to the realization of a new, wholesome society—a veritable “new form of life”—with a leap of faith that artistic talent could be redirected somehow to the practical business of organizing The New Life. The slogan “art into production” was in the ascendancy in the USSR, and the same rational, utilitarian outlook infused artistic movements to the west of Russia.

But a number of vexing issues never receded when it came to the role of art in the new society. Most obvious was the term itself. The avant-garde contingent, having already been moving in that direction, gladly declared war on art for its tendency to promote the mystifications of religion that they despised—art as soul mongering, not social production. But however much they embraced the new slogans like production and organization, the practitioners remained “artists.” It was a tar baby they couldn’t shake, however much they conceived themselves as “workers,” participants in the great revolution of the proletariat.

When these debates filtered into Europe, where the prospect of new social formations was fast receding, it was a less politically strident model of Constructivism that took hold. Berlin Dada prefigured the split within its own ranks. Heartfield, Herzfelde, and Grosz were the political ideologues of the group, dedicating their Dada “products” to Communism, while others like Hausmann and Höch made use of the same artistic innovations in works that could be sharply critical of the soft belly of the German bourgeoisie but advocated no particular political program. In short order, this division within the Berlin Dada scene would come to have serious implications for Constructivism, as well.

During 1921, as Constructivism was hotly debated in the USSR, Dada was undergoing final convulsions in Paris. Tristan Tzara persisted in the quixotic task of making Dada a household name in France, while some of his companions in Dada were pressing forward into Constructivism.

The next year, as the last phlegmatic expectorations and public bickering dissolved any pretense that Dada had fuel left in its tank, Constructivism blossomed, especially in Germany. In February and March a Constructivist group was formed in the studio of Hans Richter in Berlin, drawing on the bounty of foreigners then flocking into the city. A Hungarian, a Russian, and a Dutchman were at the heart of it, and their stories provide a vivid picture of Dada’s durable if waning force.

By this point Dada was known far and wide, sometimes regarded as run aground, sometimes as a lingering potentiality. Dada’s exploits may have achieved legendary status, but it seemed increasingly a thing of the past. Looking back on the early twenties from mid-decade, Prague writer Bedřich Václavek weighed the benefits of Dada even as he clearly thought its moment had passed. Czechs “missed out on a strong dose of Dada after the war,” he lamented, and had to proceed without the torch of Dada to clear dense cultural underbrush. As the Constructivist initiative gained momentum throughout Europe, it was often thought to follow in the wake of a salutary cleansing provided by Dada.

Such was the news brought back to Japan by Tomoyoshi Murayama in early 1923 after a sojourn in Berlin, confirming for his avant-garde countrymen that Dada and Constructivism were meaningfully related. Dada was not only associated with grand refusals and negations, its spirited defiance was salutary. The advent of Constructivism provided Dadaists with a renewed focus and an outlet for productive energies. Insofar as Dada truculence persisted, it could be seen as a healthy readjustment and training in deportment that the new age required. After all, being a Constructivist demanded almost as much militancy as being a Dadaist.

The first of the aspiring Constructivists to make his way in Berlin was Moholy-Nagy. Nagy being a common Hungarian name, he hyphenated the place name to set it off and was commonly referred to in the short form Moholy. By the time he arrived in Berlin he was twenty-five, still shaking off his military service during the war and the revolutionary aftermath in his native land. Béla Kun had established a short-lived Soviet Republic in Hungary, to which Moholy-Nagy, like most of his compatriots in art, sought to lend his support. Once it was overthrown, he joined a community of exiles in Vienna. They strongly identified with the international avant-garde, filtered through the journal Ma, edited by Lajos Kassák, first in Budapest then in Vienna (just up the street from Freud’s house). Kassák thought of Dada as “the tragic scream of our entire social existence,” a formulation suggesting that the political disappointment of the Hungarian revolution infused his group with an outlook comparable to the Berlin Dadaists a few years earlier.

Soon after Moholy-Nagy arrived in Berlin, he picked up the latest issue of Der Sturm and was incensed by what he saw. Writing a friend, he complained about “a man named Kurt Schwitters who makes up pictures from newspaper clippings, railway tickets, hairs and hoops. What’s the point?” Moholy-Nagy seems to have had no prior exposure to Merz or Dada, and at that point had no appreciation for the artistic fertility of Schwitters’ scavenging. He did learn at least tangentially of Dada, since a few weeks later he paid a visit to Herwarth Walden, impresario of Der Sturm gallery and journal, accompanied by the Rumanian artist Arthur Segal, who had participated in Zurich Dada exhibits and activities. Earlier, he’d spent time in Budapest with Emil Szittya, a peripheral participant in the Zurich scene. Despite his indignation at the Merz pictures, Moholy-Nagy soon realized that whatever was going to emerge from the morass of available isms in art would have to come to terms with Dada. Besides, he was avid to absorb all the available trends in his relentless search for the new.

Moholy-Nagy “never wanted to be left out of anything ‘new,’” said fellow Hungarian Sándor Ék. “Even within his circle of friends they sarcastically referred to him as ‘fast runner’ [Schnelläufer], who, no matter what the cost, did not wish to be left behind in the race for ‘originality.’” And what could be more original than Dada?

Moholy-Nagy’s constant scramble to assimilate the new, as seen by Ék and others, reflected his lack of formal art training. He’d had a few lessons with an eminent Hungarian painter in his youth, but that was all. He was a genuine dilettante, a term the Dadaists embraced in their own declarations, proclaiming the virtue of being untutored but ready for anything. The subtitle of Max Ernst’s Cologne Dada journal Die Schammade was “dilettantes rise up,” a slogan adapted for the International Dada Fair in Berlin, “Dilettantes rise up against art!” As a dilettante, Moholy-Nagy would soon have to come to terms with Dada.

Writing for his fellow Hungarians, Moholy-Nagy profiled the modern trends as he saw them.

Modern man . . . burst open his inherited fetters (Impressionism), and then he tried to create a new unity from the broken pieces (Cubism, Futurism, Expressionism). Once he realized that he could not create something new out of the bits and pieces of the old, he scattered the pieces to the winds with an impotent, desperate laugh (Dadaism). There was new work to be done; for a new ordering of a new world the need arose once again to take possession of the simplest elements of expression, color, form, matter, space.

This passage, along with an offhand reference to “Dadaist gibberish,” reveals Moholy-Nagy’s lingering discomfort with Dada. But the discomfort was assuaged by personal acquaintance with a number of actual Dadaists. He began frequenting Raoul Hausmann’s studio in which no distinction was made between Dadaists and other innovators. Also, Hausmann’s father was Hungarian, so they had something in common apart from their artistic interests. Moholy-Nagy even signed a “Manifesto of Elemental Art” with Hausmann, Arp, and Russian artist Ivan Puni, published in De Stijl in 1921. He was straddling two worlds, however. In the Hungarian periodicals to which he contributed (with impunity, in his native tongue), he sounded a sharply political note and even cosigned an indictment of the reformist platform of De Stijl as typical bourgeois aestheticism—while at the same time he was fraternizing with its editor van Doesburg and publishing in his journal.

“Production–Reproduction,” an essay by Moholy-Nagy published in De Stijl, July 1922, was a kind of ground plan for his life’s work that would take him from the Weimar Bauhaus to the New Bauhaus in Chicago. This essay was indebted to Dada, not least by association. Moholy-Nagy absorbed the biocentric principles of Hausmann, regarding the potential of art to enhance the receptivity of the organism. The sensibility could be stimulated by art in the more traditional sense of reproduction—art as mimesis—or by investigating the productive potential of new technologies, generating original content. In his essay, Moholy-Nagy salutes the abstract films of Viking Eggeling and Hans Richter for instigating “new kinetic realities.” “We are faced today,” he later wrote in The New Vision, “with nothing less than the reconquest of the biological bases of human life.”

In another essay, “Dynamic Constructive System of Forces” published in Der Sturm, Moholy-Nagy and coauthor Alfred Keményi envision a scenario in which “man, hitherto merely receptive in his observation of works of art, experiences a heightening of his own faculties, and becomes himself an active partner with the forces unfolding themselves.” This was a model of Constructivism as biodynamic training, “incessantly initiatory” in the words of fellow Hungarian Ernő Kállai, who regarded Moholy-Nagy’s work as “reaching out on the borders of Cubism and Dadaism.”

Moholy-Nagy’s debt to Dada is evident in his art. Before coming to Berlin he was producing mechanomorphic diagrams closely resembling those of Picabia, which were published in Kassák’s journal Ma and issued as a book in Kassák’s Horizont series. Once in Berlin, however, he fell under the spell of Schwitters and produced topsy-turvy asteroids of numbers, letters, and geometric elements coagulating in space, much like those Schwitters was exhibiting at Sturm Gallery, where Moholy-Nagy had his own first success. He was initially put off by Herwarth Walden, writing a Hungarian friend, “Just as a Dadaist journal correctly stated: he is enriching and decorating his financial genius with plundered intellectual rags, and art serves him as a disguise in making money”—a statement that reveals the credence he placed in Dada resources even as he was prone to relegate Dada to the dustbin of history. Of course his view changed once his work was taken up by this impresario of the international avant-garde.

The impact of the Sturm exhibit on Moholy-Nagy’s peers was immediate. Russian Constructivist El Lissitzky hailed it as a reprimand to “jellyfish-like German non-objective painting.” A reviewer in Frankfurter Zeitung was unstinting in his praise:

It takes discipline to be modern. This is where the artistic and the arty part company. Moholy-Nagy has the iron discipline of a scientist. Many men paint Constructivistic, but no one paints as he does. Don’t talk about coldness, mechanization; this is sensuality refined to its most sublimated expression. It is emotion made world-wide and world-binding.

Clearly, this author recognized that the austere geometric tendencies associated with De Stijl and the protocols of Neoplasticism embodied by the painting of Piet Mondrian, to which Moholy-Nagy’s work bore a superficial resemblance, harbored more than met the eye. Shortly after the war, in fact, when Moholy-Nagy returned to civilian life after years of military service, he wondered whether there was any value in art. The revelation came when he saw “It is my gift to project my vitality . . . I can give life as a painter.”

It may have been his personal sense of vitality that finally led Moholy-Nagy to recognize a similar vigor in the Dadaists with whom he came in contact in Berlin. Dada negation was a force, not simply a dispirited wail. When he and Kassák assembled a visual primer called Book of New Artists in 1922, they integrated the destructive verve of Dada into their overall understanding of artistic potential. “Here are the most energetic of the destroyers, and here are the most fanatical of the builders,” Kassák wrote in the preface. In an issue of Ma in October 1922, Kassák published one of his “picture-architecture” poems that read, in variable type sizes, “Demolish so that you can build and build so that you can triumph.” Moholy-Nagy, Kassák, and others developing alliances with Constructivism found they had to come to grips with Dada to unleash the cultural revolution to which they aspired.

When Moholy-Nagy visited Kassák and the circle of Hungarian refugees in Vienna for five weeks early in 1921, he found a milieu steeped in Dada. Kassák’s wife, Jolán Simon, was a stage veteran and just before Moholy-Nagy’s arrival had performed work by Huelsenbeck and Schwitters at a matinee at which fellow Hungarian Sándor Barta premiered his Dada manifesto, “The Green Headed Man.” Of Simon’s rendition, a reviewer wrote: “This tragic woman drew the most ghostly secrets out of Huelsenbeck’s poems with her astonishingly thin voice. She cried the sequences of senseless sounds (trivial and desperate substitutes for everything inexpressible) so that she achieved a fuller and richer expression of misery than any epic could have achieved.”

As Berlin correspondent for Ma, Moholy-Nagy served as a practical conduit for Hausmann, Schwitters, and others to appear frequently in the journal. It was a great occasion for Hungarians exiled in Berlin when Kassák and Simon visited the city in November 1923 and performed at Sturm Gallery with recitations of Schwitters, Arp, and Huelsenbeck in Hungarian. German Dada had long since run its course by then, but translation and absorption into other cultures and languages persisted in a slow rolling thunder.

Dada promoted unfettered individualism, but resisted Expressionist absorption in spirituality and pathos. When a group of students at the Bauhaus formed an organization called KURI—standing for Constructive, Utilitarian, Rational, International—they attributed to Dada “destruction as a mode of analysis” and pronounced themselves “free from the zigzag ornamentation, the chaotic disorder and increasing ecstasy of expressionism.” This ecstatic Expressionist effluvium permeated fashionable Berlin galleries, where the paintings struck Ilya Ehrenburg as nothing “but the hysterical outbursts of people armed with brushes and tubes of paint in place of revolvers and bombs.” Such work, he found, lacked all restraint and sense of proportion: “the pictures shrieked.” Ernő Kállai likewise saw “nothing of building, of logic, of construction. Everything is personal experience, again and again only ‘personal experience.’” The old art cultivated personality, inwardness, and a transaction between artist and viewer based on aesthetic contemplation. The geometric order of Constructivism was not meant to nourish contemplative tranquility. These works were blueprints and models.

Constructivists had a number of different ideas about the role that art could play in the postwar world. One of the most rigorous of these was developed by a Russian in Berlin whose closest companions were Dada veterans. He was El Lissitzky, Russian emissary of Constructivism in the West, who coined the term Proun (short for “projects affirming the new”) for his artworks, which he regarded as way stations for the future, models for a utopia. He had a dramatic sense of the generation into which he was born in 1891. “We were brought up in the age of inventions. When five years old, I heard Edison’s phonograph—when eight, the first tramcar—when ten, the first cinema—then airship, aeroplane, radio. Our feelings are equipped with instruments which magnify or diminish.” The machine ensemble was a model, and “we need the machine,” Moholy-Nagy wrote. “We need it, free from romanticism.”

Artists like Lissitzky and Moholy-Nagy shared a growing sense that the practice of painting could produce a preparatory document, not aesthetic finality. “The collectivity of a picture manufactured in a series lies in the fact that one may take it home,” Kállai optimistically forecast, and “store or exchange it like a gramophone record.” He hadn’t reckoned with commodity fetishism, but he was anticipating the phenomenon André Malraux dubbed a museum without walls—now ubiquitous on the Internet, since the proprietary relationship to images is presumably swept away because of their universal accessibility.

These optimistic Constructivist models were worked out under challenging circumstances. American writer Matthew Josephson, coming from the inner sanctum of Paris Dada, found a very different milieu in Berlin. Unlike the French, these artists didn’t hang out in cafés. Josephson became friends with Lissitzky, who one day escorted him to Moholy-Nagy’s “barnlike studio.”

Though Moholy lived in dire poverty at the time and boasted no furniture in his big studio, he was a most gallant host. The place was decorated with abstract paintings of his own as well as with machine-sculptures by the Russians Lissitzky, Gabo, and Vladimir Tatlin. . . The Constructivists were threadbare; their women were dressed in shapeless clothes; but they were gay and full of hope and big ideas. Moholy had us all sit down on packing boxes covered with some colored cloth, which were arranged in a circle around a huge bowl of soup in the center of the floor space. We guests advanced with our smaller bowls, filled them with the excellent mess, and returned to our packing boxes, making merry the whole evening over some weak table wine.

Josephson’s impression of Lissitzky was typical. Universally welcomed, he was an instant member of the family. Short, balding, perennially sucking on his pipe, with a constant twinkle in his eye, Lissitzky comes across in memoirs as the Bilbo Baggins of his kind. Unassuming and unimposing, he was everyone’s favorite houseguest.

Lissitzky was also a fireball of creative intensity. Ehrenburg left an endearing portrait of his friend. “In ordinary life he was mild, exceedingly kind, at times naïve; he was often ill; he fell in love in the way that people used to fall in love in the past century—blindly, self-sacrificingly,” he recalled. “But in art he was like a fanatical mathematician, finding his inspiration in precision and working himself up over austerity.” His German was good (if heavily accented), as he’d attended architecture school in Darmstadt, the Russian schools being closed to him as a Jew. His early career was spent illustrating and designing Yiddish publications, but in 1919 he returned to his native city of Vitebsk, joining the faculty at the Artistic-Technical Institute established by Marc Chagall. There he became allied with Kazimir Malevich, imperious founder of Suprematism and archrival of Tatlin. They formed a group within the institute called UNOVIS, acronym for Affirmers of the New Art.

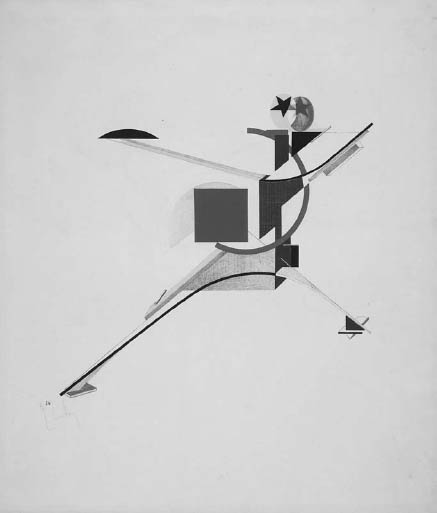

El Lissitzky, The New Man, a Proun from Victory over the Sun (1923).

Copyright © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

The paintings Lissitzky executed under the category Proun bear out his sense of humankind hurtling into a future inconceivable only a generation earlier. The images in his Proun paintings simultaneously occupy different scales: the lozenge-like free-floating assemblages can be microscopic or galactic. Kállai wrote several articles on the Proun works, suggesting they be compared “to an airman’s sensation of space” emancipated from gravity. “The diagonals of a spider’s web of razor-sharp, straight lines strive to reach the tip of a Utopian antenna or wireless mast. A technical planetary system keeps its balance, describes the elliptical paths or sends elongated constructions with fixed wings out into the distance, aeroplanes of infinity.”

Kállai was shrewd enough to recognize this was “romanticism in disguise,” but that didn’t deter his admiration. They might be “fictive constructions of fictive mechanisms” and even resemble three-dimensional objects, but they were “immediately recognizable as figments of the imagination.” Lissitzky himself would have argued that all inventions first begin as figments in the mind, then are nurtured in the laboratory of mechanical experimentation until an application emerges. So he regarded his Prouns as testing platforms meant to orient mind and body to an emergent sensation of spatiality. “The surface of the Proun ceases to be a picture and turns into a structure round which we must circle, looking at it from all sides, peering down from above, investigating from below,” Lissitzky wrote. “Circling round it, we screw ourselves into the space.” However much the space evokes the drafting board, Lissitzky regarded these way stations “rising on the ground fertilized by the dead bodies of pictures and their painters.” As lines like these indicate, he had a bit of the Dada snarl in his bones, fortified by the Bolshevik Revolution.

Lissitzky recognized that Dada and Constructivism shared a renunciation of “art.” Writing to the owner of a Proun, who enquired, innocently enough, about how to hang the painting, Lissitzky noted that the household in question had carpets on the floor and plaster cupids on the ceiling. “When I made my Proun,” he wrote, “I did not think of filling one of these surfaces with yet another decorative patch.” Lissitzky set to work designing spaces suitable for his Prouns and the work of his Constructivist peers. “We no longer want the room to be like a painted coffin for our living body,” he said.

Other marked similarities could be seen between Lissitzky’s brand of Constructivism and Dada. He designed a Proun Room for the Great Art Exhibition in Berlin in 1923 on the aggressive principle that “we are destroying the wall as a resting place for the pictures” of conventional artists. Two display spaces followed in 1927—“Space for Constructivist Art” in Dresden and “Abstract Cabinet” in Hanover—as he purified his mission of alleviating Constructivist work from the malady of the market. “The great international picture-reviews resemble a zoo,” he argued, “where the visitors are roared at by a thousand different beasts at the same time.” The work he saw himself and his allies producing did not clamor for attention in this subservient capacity, but anticipated a new world order: “Our painting will be applied to the whole of this still-to-be-built world,” he wrote, “and will transform the roughness of concrete the smoothness of metal and the reflection of glass into the outer membrane of the new life.”

When Lissitzky arrived in Berlin in 1921, more than three hundred thousand Russians were living in the city, many of them fleeing the revolution, but a considerable number were intent on reestablishing cultural and political relations between Germany and the Soviet Union. Everywhere on the streets one could hear Russian spoken. Marc Chagall recalled that he’d never seen so many rabbis or Constructivists at once. In this teeming petri dish, Dada and Constructivism would combine to make an entirely new life-form.

Lissitzky arrived with a mission to spread the gospel of the new Russian art. He and Ehrenburg had modest funds to launch a journal, trilingual for maximum impact: Veshch/Objet/Gegenstand. It was propaganda of sorts for Constructivist initiatives coming from the Soviet Union, but the editors were reluctant to embrace the hard line of productivism: “No one should imagine,” they wrote, “that by objects we mean expressly functional objects.” They still envisioned a place for art, even as they adhered to a Marxist outlook: “We are unable to imagine any creation of new forms in art that is not linked to the transformation of social forms.” Lest the journal’s title mislead anyone, they spelled out exactly what the object meant to them:

Every organized work—whether it be a house, a poem, or a picture, is an “object” directed toward a particular end, which is calculated not to turn people away from life, but to summon them to make their contribution toward life’s organization. So we have nothing in common with those poets who propose in verse that verse should no longer be written, or with those painters who use painting as a means of propaganda for the abandonment of painting. Primitive utilitarianism is far from being our doctrine. Objet considers poetry, plastic form, theater, as “objects” that cannot be dispensed with.

Insisting on the international character of modern art, Lissitzky and Ehrenburg acknowledged the “negative tactics of the ‘Dadaists’” as a necessary precondition, even as they judged that “the days of destroying, laying siege, and undermining lie behind us.” This theme was taken up almost like a collective international chorus, passing from one journal to another during the next few years. But as Constructivism gained momentum, it would never be altogether free of Dada’s “negative tactics.” The intransigence of old attitudes about art persisted, and the utopian outlook of Constructivism needed the battering ram of Dada to confront it.

Soon after arriving in Berlin, Lissitzky met George Grosz, who put him in touch with his fellow Dadaists. Before long Lissitzky was hanging out with Hausmann, Höch, Richter, and Moholy-Nagy. He became particularly attached to Kurt Schwitters, who towered over the diminutive Russian.

Lizzitzky and Schwitters made quite a pair, and not because they were so mismatched physically. Schwitters introduced the Russian to Sophie Küppers, widow of the former director of the Kestner Society in Hanover. She’d been enthralled by the Prouns on display at the First Russian Show in Berlin and arranged for an exhibition of Lissitzky’s work, which he suggested be supplemented with work by Moholy-Nagy. She also arranged for him to lecture on the new Russian art, as well as the publication of a Proun portfolio. In return, with the modest means at his disposal, he escorted her to a Chaplin film in Berlin, inaugurating a slow but steady courtship that led to marriage.

Frequenting the circle of Dadaists in Berlin and Hanover hardly made Lissitzky a Dadaist, and by the time he became enmeshed in this scene there were no more Dada events in Berlin anyway. Yet some thought him a Dada insider, like Louis Lozowick, an American artist of the same generation. Because Lozowick encountered Lissitzky often in the company of the Berlin Dadaists, he extended his puzzlement to the Russian. “I could never understand how a man like Lissitzky, quiet, well-behaved, and straightforward, could belong to the group,” he wrote. Another figure Lozowick met on his travels was van Doesburg, editor of De Stijl, a man “ready to explain his theories to anyone willing to listen” and, like the Dadaists, perplexing the American artist by looking “more like a businessman than a rebel.”

The complexity of van Doesburg’s personality begins with his name. He was born Christian Emil Küpper in Utrecht in 1883. His father was out of the picture before he was born, so when he started painting as a teenager he signed his canvases Theo van Doesburg, the “van” indicating the name derived from his stepfather. There were more names to come. In 1917 he told a friend he was thinking of using Küpper as a pseudonym and mentioned he was already publishing articles under the nom de plume Pipifox. In a few years, I. K. Bonset and Aldo Camini would be added to his repertoire of pseudonyms. He started the journal De Stijl in 1917, which for several years was mainly invested in modern architecture and design, regularly publishing work by Dutch architects J. J. P. Oud and Gerrit Rietveld, among others.

The most frequent contributor to De Stijl was the older painter Piet Mondrian, a theosophist like Kandinsky, bent on calibrating the primary ingredients of the universe with his grid-like canvases and adherence to primary colors. Van Doesburg and other De Stijl artists like Bart van der Leck and the Hungarian Vilmos Huszár produced subtle variants of the Mondrian grid.

It was all very rational and sober, just the opposite of Dada. Esoteric rites of artistic purification notwithstanding, these men were absorbed in everyday life and the practical business of architecture and urban planning. When the war ended and it was possible to travel in France and Germany, however, the world was revealed to them anew—and one of its revelations was Dada.

On an uncommonly warm day early in 1920, van Doesburg and Mondrian were sitting at a sidewalk café in Paris, luxuriating in the sights and sounds of the buzzing thoroughfare. Mondrian, van Doesburg wrote to a friend, “has been inspired by the immense machine that is Paris”—“a highly complex machine,” he added, “but when one understands the structure it is marvelous how quickly one becomes one with it.”

Mondrian was sketching an article on “The Grand Boulevards” in which he came to regard the city street as a “thought concentrator.” “Everything on the boulevard moves,” he wrote. “To move: to create and to annihilate.” All this motion decomposed the static unities, resulting in something like a live-action model of a Schwitters collage: “Negro head, widow’s veil, Parisienne’s shoes, soldiers legs, cart wheel, Parisienne’s ankles, piece of pavement, part of a fat man, walking-stick nob, piece of a newspaper, lamp post base, red feather.” As these fragments swim into view, “they compose another reality that confounds our habitual conception of reality,” producing however not a chaotic throng but “a unity of broken images, automatically perceived.” The key term here is automatically, because Mondrian recognized something later theorized by the German writer Walter Benjamin—namely, that modern life cannot be absorbed by quiet contemplation but is grasped in a state of distraction, bit by bit. “The particular carries me away,” Mondrian wrote, adding “that is the boulevard.”

Yielding to the constant stimulus of the modern metropolis was an initiation of sorts into the outlook extolled by the Dadaists. Mondrian had returned to Paris (his home for a few years before the war) in 1919, so getting reacquainted with the city meant being confronted with Dada’s French debut. In the summer of 1920 Mondrian signed a letter to van Doesburg, “Your friend, Piet-Dada.” No one has ever considered Mondrian a Dadaist, least of all himself (“it was nice to show enthusiasm,” Mondrian wrote, “but in the long run we just aren’t dada”), but Piet-Dada acknowledges a moment of influx. You could absorb Dada without becoming one: sitting at a café was enough to make it happen—at least with Theo van Doesburg at hand.

Two years earlier, van Doesburg had a revelation commensurate with Mondrian’s, but instead of being prompted by city streets, it was an American export, courtesy of Hollywood. He gushed about the experience to his architect friend Oud:

In maximum movement and light you saw people falling apart, into ever smaller planes which in the same instant reconstituted themselves into bodies. Continual death and rebirth in the same moment. The abolition of time and space! The destruction of gravity! The secret of 4-dimensional movement. Le Mouvement Perpétuel. What miracles American film achieves. How it disrupts closed volumes. What perspectives it opens to the thinking mind. How can it reveal the secret of universal movement: the secret of the rotation of a body on a surface? Why does one seek to solve this with figures on paper? Enough of that. Go watch a film. Not a slow one where the flowing curves of bodies are the outer limit, a surface, but the rapid, angular, sharp-edged one that deconstructs bodies to planes, to flat fragments, to points, and which in this most marvelous of all games unfolds the secret of the cosmic structure, makes visible that which happens invisibly to everyone’s body: destruction and reconstruction in the same instant.

Allowing for the fact that only an artist would be inclined to see in common movie fare a rival version of abstract painting as pioneered by Kandinsky and Mondrian, this is also an exhortation to be modern. And that’s what Mondrian meant by adding Dada to Piet.

In 1918, then, a year after embarking on the course of De Stijl, van Doesburg had his exhilarating vision of “destruction and reconstruction in the same instant.” It was a tantalizing blend, reflecting in part the path already taken by Mondrian and Bart van der Leck in their deliberate paring away of the bulky clutter of appearance with its profusion of details. They’d arrived at their pure geometric coordinates by literally ab-stracting, that is pulling apart, the subjects of their paintings, dissolving the flesh of experience so only the bones remained. They—and van Doesburg—conceived this process in terms of purification; in fact, there was a pure core of dissolution at the heart of it. But what if the destruction were outed, so it shared the labor “at the same instant” with “reconstruction”? Posed as a what if, the realization crossed van Doesburg’s mind in the movie theater that there was a tendency abroad in the world capable of bearing that burden of destruction: Dada.

It wasn’t as if van Doesburg was unfamiliar with the process. In 1916, while serving in the military (as a noncombatant, as Holland was not at war), he adopted a radical strategy of reducing naturalistic depiction to its bare minimum. He called it “destroying.” It took him several years, though, to acknowledge the pertinence to his strategy of the Dada initiative under way at the same time at Cabaret Voltaire. In 1920 he wrote to De Stijl contributor, the painter Georges Vantongerloo, “Only those who perpetually destroy what is behind them to rebuild themselves for the future can arrive at the new and the true.” In October 1921 he told Tzara: “The Dadaist spirit pleases me more and more. There is a desire for something new similar to that with which we proclaimed the modernist ideal.” Importantly, “I believe in the possibility of really meaningful contact (and synthesis) between Dada and developments in ‘serious modern’ art.” It’s ironic that soon after this letter André Breton would propose his ill-fated Congress of Paris to investigate the modernist ideal. Van Doesburg now realized that Dada and De Stijl (plus Constructivism more broadly) might be allies. “It is only the means that are different.”

When he wrote Tzara, van Doesburg was living in Weimar, the city famously associated with Goethe and Schiller, but now a conservative municipality nervously eyeing the new arts academy, Bauhaus, founded by architect Walter Gropius a year earlier. The affinities van Doesburg assumed would exist between the Bauhaus and De Stijl were not what he’d hoped, however.

The Bauhaus in this early period had a cultic aura, much of which derived from Mazdaznan, an American-born neo-Zoroastrian religion that reached Europe in 1907. Johannes Itten integrated Mazdaznan practices into his teaching curriculum, mandatory for all students because he taught the school’s preliminary course. Practices included loose robes, shaved heads, meditation, purification rituals, colonic irrigation, and a vegetarian diet. Itten was instrumental in focusing the Bauhaus on this peculiar combination of modern technology and ancient cult.

When van Doesburg arrived in Weimar, he was taken aback, finding the Bauhaus “sick with the pépie of Mazdaznan and wireless expressionism” (a reference to the vogue for depicting modern objects like telephones and petrol pumps in paintings). El Lissitzky also found the place bewildering: “The criminals in Russia were formerly branded on the back with a red diamond ♦ and deported to Siberia. In addition, they had half their hair shaved off their heads. Here in Weimar, the Bauhaus puts its stamp—the red square—on everything, front and back. I believe the people have also shaved their heads.” Confronting this odd mix of esotericism and progressive teaching institution, van Doesburg promptly disseminated “the poison of the New Spirit” by setting up a studio right across the street and recruiting Bauhaus students for informal (and eventually formal) seminars and workshops.

With his expertise in stained glass, architecture, painting, poetry, music, typography, and writing, van Doesburg could reasonably present himself as a one-man alternative to the Bauhaus. He’d spent several years doing glass designs by absorbing the structural imprint of Bach’s preludes and fugues, along with the musical compositions of his contemporaries: Arnold Schoenberg, Erik Satie, Josef Hauer, Arthur Honegger, Francis Poulenc, Darius Milhaud, and George Antheil. The architectonics of music translated readily into abstraction, in which lines could be pulses, circles condense into points on a graph and then bounce, as both Kandinsky and Walt Disney would elaborate. The musical instinct was enhanced when van Doesburg met pianist Petronella van Moorsel, who became his third and final wife and essential participant in the Dada tour he undertook with Kurt Schwitters.

Van Doesburg’s alliance with Schwitters developed in the wake of two momentous Constructivist conferences of 1922. Early in the year he visited Berlin, which was a cross-cultural stew as Russians both Red and White continued to pour into the city. There he called on Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling, who were immersed in their search for a universal language of visual signs, leading at first to sequential scrolls, from which they then made the leap into film. Abstract film. What Richter was doing on film stock bore a striking resemblance to the geometric purifications of De Stijl. He was setting lozenges in motion: squares and lines mostly, elongated and shortened, expanded and compressed in visual counterpoint. The films were no more than two minutes long, and Richter called them rhythm studies.

The challenge of working with a medium like film was financial. Van Doesburg suggested to Richter that he might start up a magazine to generate revenue. The result was G

![]() , but the journal didn’t appear until 1923. Back in Richter’s Berlin studio in early 1921, a group of individuals committed to Constructivism was gathering. These included the Russians Gabo, Pevsner, Natan Altmann, and Lissitzky; the Hungarians Moholy-Nagy, Alfréd Kemény, Ernő Kállai, and László Péri; van Doesburg and Cornelis van Eesteren from Holland; the Germans Willi Baumeister, Werner Graeff, and Mies van der Rohe; and from Zurich Dada days, Viking Eggeling and Hans Arp, the latter making one of his periodic visits to German cities like Berlin, Hanover, and Cologne where a spark of Dada still glimmered.

, but the journal didn’t appear until 1923. Back in Richter’s Berlin studio in early 1921, a group of individuals committed to Constructivism was gathering. These included the Russians Gabo, Pevsner, Natan Altmann, and Lissitzky; the Hungarians Moholy-Nagy, Alfréd Kemény, Ernő Kállai, and László Péri; van Doesburg and Cornelis van Eesteren from Holland; the Germans Willi Baumeister, Werner Graeff, and Mies van der Rohe; and from Zurich Dada days, Viking Eggeling and Hans Arp, the latter making one of his periodic visits to German cities like Berlin, Hanover, and Cologne where a spark of Dada still glimmered.

Van Doesburg recognized the potential of this lingering spark as he assessed the German milieu. The Bauhaus was constrained by its anachronistic crafts sensibility and the smoldering fever of Expressionism, while elsewhere the more progressive tendencies affiliated with Expressionism, like the Novembergruppe, were retracting their political claws and hedging their bets, anticipating a revived art market. Van Doesburg might be described as a non-political revolutionary, bent on social change by driving an austere aesthetic wedge right through the middle; but the architectural and artistic models to which he appealed were practically spiritual in their idealism. Yet he was no theosophist like Mondrian and kept hammering away at the need for social reform. He laid out the principles in a lecture he gave throughout Germany, advocating for

definiteness instead of indefiniteness

openness instead of closedness

clarity instead of vagueness

religious energy instead of belief and religious authority

truth instead of beauty

simplicity instead of complexity

relation instead of form

synthesis instead of analysis

logical construction instead of lyrical representation

mechanical form instead of handiwork

creative expression instead of mimeticism and decorative ornament

collectivity instead of individualism

Van Doesburg cited, as evidence of this “will towards a new style,” a broad range of activities in the arts, architecture, literature, jazz, and cinema. Van Doesburg differed from most of his allies from other countries about the purpose of this “new style.” Instead of the explicitly political Third International, he spoke of an “International of the Mind” motivating “the exponents of the new spirit,” whose “wish is solely to give. Gratuitously.” But after the political crisis of the 1918 November Revolution, Dadaists and Expressionists alike promoted art as a weapon in the class struggle. Various artists’ collectives arose, like the Worker’s Council of the Spirit and the Novembergruppe. Identifying the future of art with a spiritual revolution awakened by the avant-garde, the Novembergruppe momentarily galvanized progressive artists in Germany.

By 1921, however, the Dadaists denounced the Novembegruppe’s pledge of solidarity with the working class as opportunistic jockeying for preeminence in the art market. The organization, they said, had subsided to “petty trading in aesthetic formulas” led by “a dictatorship of the aesthetes and businessmen.” Rather than “attempting to reject the role of drone and prostitute forced on the artists in capitalist society, the leaders did everything to further their own interests with the help of a rubber stamp membership.” This withering assessment was about to come to a head in an arts congress in Düsseldorf.

While Hans Richter was organizing his Constructivist group in February 1922, a more extensive assembly formed as Union of International Progressive Artists. Under the leadership of Gert Wollheim, director of the artist’s collective Junge Rheinland, they set about organizing a large exhibition for late May in Düsseldorf, with an accompanying congress on May 29–31, 1922, called the First International Congress of Progressive Artists. Kandinsky provided a brief forward to the exhibition catalogue, reiterating the grand utopian themes from his Blue Rider days. “Everything trembles and shows its Inner Face,” he wrote in terms agreeable to Expressionism. The new world will be revealed courtesy of “Inner Necessity.” “Thus the Epoch of the Great Spiritual has begun,” he triumphantly concluded. It’s indicative of the oncoming rift between the Constructivists and the “progressive” artists, that only the latter group would have welcomed the terms with which Kandinsky appraised the future of art. After all, he’d recently been forced out of INKhUK in Moscow by the Working Group of Constructivists.

The congress in Düsseldorf opened without incident, the first day spent on organizational issues such as identifying and electing representatives for each of the constituencies. Van Doesburg, Richter, and Lissitzky did object, however, to the presumption that all in attendance would sign a collective pledge declaring art to be “international.” At their insistence, the document was amended so it was basically a record of who was in attendance. The conference was genuinely international, with attendees coming from as far as Japan, though the very setting in the capital city of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia gave the regional German artists a misguided confidence in their own priorities.

Richter and his allies were in for a shock the next day, when a manifesto was read, identifying the union as a practical and economically oriented interest group of artists. Such a blatant resurrection of the art market spurned by the Berlin Dadaists was equally repugnant to the Constructivists in Richter’s group, who made a stink by denouncing the proceedings and walking out with loud cries of protest.

On the third and final day the delegates of protesting factions read statements, including van Doesburg for De Stijl, Lissitzky for Objet, and Richter for a loose amalgamation of artists from Rumania, Switzerland, Scandinavia, and Germany. After a lunch break, Raoul Hausmann applied the perfect Dada touch by announcing he was no more “international” than he was a cannibal. He then stormily exited the building, followed by the protesting groups. Van Doesburg described the scene to a fellow artist back in Holland. “In the end, of course, we had to leave the hall with vigorous protest, as it turned out to be a big mess. It was all based on commercial interests!” But at least they knew where they stood: “We now know whom we can expect to be dealing with in future congresses. The Futurists, Dadaists and a few others left the building with us.”

After the departure of the Dadaists and their allies, the congress subsided into inconsequentiality. An art critic witheringly observed, “After the departures the Congress made positive advances, since there were no more points of dispute and everything was as boring as if the place were filled with government officials. German organization held its own.”

Although the congress didn’t accomplish much on its own terms, it did inspire a healthy—and productive—backlash from the Constructivists that would ally them with the former Dadaists they now counted in their ranks. In just a matter of weeks, a special congress issue of De Stijl was published, printing the platforms of the protesting groups, which were collectively organized under the name International Faction of Constructivists (IFdK in its German acronym). The organizers of the congress had stubbornly refused to consider what made art “progressive,” despite its conspicuous presence in the group’s title. The faction, on the other hand, was more than willing to identify the progressive artist as a combatant against “lyrical arbitrariness” and “the tyranny of the subjective in art.” They denounced the Düsseldorf exhibition as little more than “a warehouse stuffed with unrelated objects, all for sale.” Most poignant, though, was the faction’s admission of its own precarious status: “Today we stand between a society that does not need us and one that does not yet exist.”

On the floor of the congress, van Doesburg had read the “Creative Demands of ‘De Stijl,’” and when published in De Stijl he indicated that two of the points were roundly applauded: one calling for the elimination of art exhibitions in order to make way for demonstrations of teamwork, and another point demanding the annulment of any distinction between life and art. The documents assembled for the congress issue of De Stijl give a vivid sense of the gulf separating the IFdK artists from the so-called progressives. The De Stijl group demanded the suppression of “subjective arbitrariness in the means of expression,” a stinging rebuke to the familiar mystification of artistic genius. In his statement, Richter (signing on behalf of Eggeling and Janco) reiterated the point that any social transformation would be achieved “only by a society that renounces the perpetuation of the private experiences of the soul.” Lissitzky, too, disavowed “those who minister to art like priests in a cloister” (the Bauhaus’ Itten was a recognizable target). His statement reiterated points from the editorial of Objet, while adding the sting that the new art was actually endangered “by those who call themselves progressive artists.”

With hostility so brazenly declared against the Union of International Progressive Artists, the aura of a benign Constructivism devoted to rational planning suddenly took on a different, more martial character. And given the background of some of the attendees—Hausmann, Höch, Richter, Janco—the specter of Dada made itself evident as a worthy ally in the struggle.

Van Doesburg realized he was at the pivot of Constructism and Dada and decided to issue a folded broadside journal with the name Mécano, combining Dada and Constructivism in equal measure. Mécano is literally dizzying to peruse, as if a robotic impetus had overtaken the art world and started issuing screen grabs, instantaneous profiles of avant-garde in the moment. Three editions of Mécano were issued in 1922, in yellow, blue, and red. Unfolded, both sides of the sheet contained a patchwork of eight segments each facing a different direction, with its own typography and images.

Encountering Mécano was like sitting at the café with “Piet-Dada.” In fact, a short statement by Mondrian ran lengthways facing a reproduction of Hausmann’s mechanical head, The Spirit of Our Time. Elsewhere on the foldout of this blue issue was a photomontage by Hausmann, adjacent to a buzz-saw blade, van Doesburg’s icon for all the issues of Mécano. It was echoed by the cogwheels in Man Ray’s photogram Dancer reproduced in the yellow issue. On the verso of the blue issue—next to Hausmann’s manifesto on sound poetry—was Moholy-Nagy’s iconic Nickel Sculpture, its metallic spiral suggesting the onset of radio transmission, which was only at that moment entering the public sphere. Among its Dadaist contributors were Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, Paul Éluard, Man Ray, Jean Crotti, Raoul Hausmann, Tristan Tzara, Hans Arp, Max Ernst, and Kurt Schwitters, most in several issues. Ezra Pound was also on hand, caught up as he was in the swirl of Dada after his move to Paris. Mondrian and others associated with De Stijl were included, along with I. K. Bonset, who nobody knew at the time was another of van Doesburg’s alter egos.

Bonset made his debut in De Stijl in May 1920, and would become a regular contributor. Van Doesburg confided to Oud that Bonset was a “splintering” of himself needed for his assaults on the old order. De Stijl’s penchant for order as such would seem inimical to aggression, so Bonset had a seismic task. Apart from Oud, others were not informed of Bonset’s identity. But van Doesburg happily dispensed a modicum of information and arranged for Bonset’s participation in the international scene, albeit by correspondence. Having heard Bonset described as “against everything and everyone,” Tzara jumped at the bait and asked van Doesburg to invite this Dutch firebrand to contribute to a Dada project. “I’m pretty sure he’ll accept,” van Doesburg replied, continuing tongue-in-cheek: “Bonset shares our ideas, but he’s a funny chap, never showing himself.” On one occasion, Tzara and Arp wrote a letter to Bonset, and van Doesburg addressed his alter ego on the back of the envelope: “You see how your reputation for invisibility is attracting ever more followers.” There was nothing invisible about Bonset’s publications, though, which bore all the hallmarks of Dada invective and civil disobedience.

The blue Mécano featured Bonset’s “Manifesto 0,96013”—its numerical title a send-up of the consecutively numbered De Stijl manifestos to which van Doesburg signed his own name. It concluded with large underlined type, dramatizing its theme as vividly as Picabia’s depiction of an ink splatter as the Virgin Saint:

Sperm Machine

Life—a venereal disease

All my prayers are dedicated to Saint Veneria

Van Doesburg clearly exulted in brandishing his venom and wit inside the puppet persona of Bonset. “Dada is the cork in the bottle of your stupidity,” he heckled in “Antiartandpurereasonmanifesto” in the yellow Mécano. “In future I will allow myself to use you as Dada’s walking-stick.”

Bonset had a regular outlet in De Stijl, courtesy of editor van Doesburg, but he also responded to Tzara’s request for material, providing several texts (like “Metallic Manifesto of Dutch Shampooing”) for Tzara’s intended Dada anthology. It never came to fruition, so they were unpublished in van Doesburg’s lifetime, but they reveal that he knew of Duchamp’s Fountain: “Art is a urinal,” Bonset wrote in “Manifesto I K B.” In another text he made passing reference to “we neovitalist Dadaists, destructive Constructivists.” Constructivism needed to hone its blade: that was the incentive behind the invention of Bonset, whose appearances in De Stijl marked him less as the raving, impertinent Dadaist reported in the press and more as a Nietzschean type, advancing beyond good and evil. So his repudiation of words like humanity, love, art, and religion, signaling standard even hackneyed concepts, as “sentimental deformations of feeling” was actually concordant with the broader mission of De Stijl as a forum for rational planning.

“The abnormal is the prerequisite of new values” was another of Bonset’s aphorisms. In his role as spokesman for Dada negation, Bonset was reasonable if blunt. “The principle of life is completely amoral,” he explained. “Before every birth there is annihilation.” And, in a yin-yang formulation as dear to van Doesburg himself as to Bonset: “No is the strongest stimulation to yes.” In a world benumbed by bourgeois complacency, its art consigned to “the immoral art brothels,” the need for a transcendent affirmation was like an ache in the soul, but simply wishing wouldn’t make it so. The hammer was no.

Short of naming his dog “Dada,” van Doesburg resisted the urge to come out of the closet and make a personal appearance as a Dadaist. He was too committed to the austere cleansing program of De Stijl for that. His taste for confrontation and the allure of the stage found in Dada an appealing venue. His alter ego Bonset was one vehicle, and Mécano was a most agreeable Dada forum. But could he make a personal appearance on behalf of Dada while maintaining the appearance of neutrality and preserving the integrity of De Stijl? That was the question he would have to come to grips with after the excitement of the Düsseldorf congress.