Recognizing Lincoln

Portrait Photography and the Physiognomy of National Character

People take awful liberties with Lincoln. . . . It almost makes you wish that Lincoln had been copyrighted.

— E.S.M., “Reproducing Lincoln,”

Life, September 6, 1917

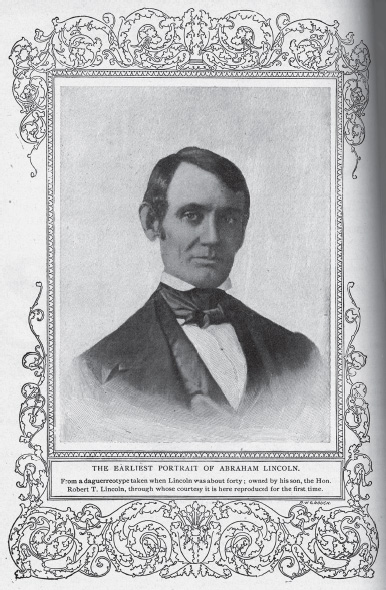

Thirty years after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, McClure’s magazine published a newly discovered image that to this day remains the earliest known photograph of Lincoln. Revealed to the American public in 1895, nearly fifty years after its creation, the daguerreotype reproduction featured a Lincoln few had seen before: a thirty-something, well-groomed, middle-class gentleman.1 Readers of the magazine greeted the image with delight. Brooklyn newspaper editor Murat Halstead rhapsodized, “This was the young man with whom the phantoms of romance dallied, the young man who recited poems and was fanciful and speculative, and in love and despair, but upon whose brow there already gleamed the illumination of intellect, the inspiration of patriotism. There were vast possibilities in this young man’s face. He could have gone anywhere and done anything. He might have been a military chieftain, a novelist, a poet, a philosopher, ah! a hero, a martyr—and yes, this young man might have been—he even was Abraham Lincoln!”2 General Francis A. Walker, president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, wrote similarly but more plainly of the photograph: “The present picture has distinctly helped me to understand the relation between Mr. Lincoln’s face and his mind and character, as shown in his life’s work. . . . To my eye it explains Mr. Lincoln far more than the most elaborate line-engraving which has been produced.”3

“The Earliest Portrait of Abraham Lincoln.” McClure’s, November 1895, 482.

The photograph itself hardly seems to inspire such broad claims or florid prose. Indeed, at first glance it is difficult to glean what exactly Walker thinks it might explain (in fact, he never tells us). The image is not particularly unusual save for the later fame of its subject. Cropped by McClure’s to highlight Lincoln’s head and shoulders, and reproduced in the pictorialist style of the era, the image nevertheless looks like a standard-issue early daguerreotype: its pose stiff and formal, body and head held firm to accommodate long exposure times of 1840s photography. Yet in this conventional image Halstead and Walker claim to see the seeds of Lincoln’s greatness, to understand his “character.”

Others who wrote letters to the magazine in response to the photograph responded similarly. In its December 1895 and January 1896 issues, McClure’s published seven full pages of letters responding to the Lincoln daguerreotype. Analysis of these letters reveals that the image posed a reading problem for those who wrote in to the magazine. A few admitted they had trouble physically recognizing the iconic president as a younger man, while others wrestled with a seeming disjuncture between the well-dressed, conventional-looking man in the photograph and Lincoln’s famed unconventional (even ugly) physicality. Still others had trouble locating in the image the affective qualities they had come to associate with Lincoln, such as his well-known melancholy. These late nineteenth-century viewers ultimately made sense of the Lincoln photograph by treating it as a vehicle for the exploration of its subject’s character. Their responses show that they saw in the image not only a Lincoln they recognized physically but one whose psychology and morality they recognized as well. Those who composed responses to the McClure’s photograph tapped into powerful myths about Lincoln that circulated during the late nineteenth century.

No figure carried more public weight in the late nineteenth century than Abraham Lincoln. Throughout his career, but particularly after his assassination, Lincoln was (and remains) a potent, contested icon.4 Photographs of Lincoln are particularly fascinating because of the staggering force of the Lincoln mythos. Although there are fewer than 120 extant photographs of him (more than half of those made during his presidential years), Lincoln was one of the earliest and arguably the most photographed political figure of the middle nineteenth century.5 By the close of the nineteenth century he had begun to surpass George Washington as the political icon of the republic.6 Indeed, he probably was the only American whose visual image could generate the kind of public response found in McClure’s.7 Yet viewers’ interpretations of Lincoln’s iconicity have never been uniform. Sociologist Barry Schwartz argues that in the fifty or so years following his death, “Lincoln was not elevated . . . because the people had discovered new facts about him, but because they had discovered new facts about themselves, and regarded him as the perfect vehicle for giving these tangible expression.”8 In short, “Lincoln’s portrait shifts depending on who is doing the remembering.”9

How did McClure’s readers in 1895 reconcile the reading problems posed by the new, yet older photograph? What shifting portrait of Lincoln did responses to the daguerreotype produce? Those who wrote letters recognized the photograph’s capacity to communicate the character of Lincoln and, by extension, the character of the American nation. The concept of character is foundational to the study of rhetorical practice; indeed, as Thomas Farrell says, “The most powerful rhetorical proof, as Aristotle noted, is ēthos—the character of the speaker as it is manifested through the speech.”10 In traditional rhetorical understandings of character, speakers display or perform their good character through offering “practical wisdom, virtue, and goodwill” in their communications.11 Yet ethos is not solely the responsibility of the speaker.

S. Michael Halloran observes that it is also about the audience and its character as a community. Ethos “indicates the importance of the orator’s mastery of the cultural heritage; through the cogency of his logical and emotional appeals he became a kind of living embodiment of that heritage, a voice of such apparent authority that the word spoken by this man was the word of communal wisdom, a word to be trusted for the weight of the man who spoke it and the tradition he spoke for.”12 A rhetorical conception of character, then, oscillates between speaker and audience, between the individual and the social, such that ethos comes to constitute what Farrell calls “the heritage of our shared appearances.”13 As a “common dwelling place of both” audience and speaker, ethos constitutes a rhetorical space for conversations “where people can deliberate about and ‘know together.’”14

Viewers seeking to make sense of the McClure’s Lincoln recognized photography’s capacity to communicate character. In the individual, subject-centered sense, photographs were understood to visualize the moral character of their subjects. Viewers of the McClure’s Lincoln readily recognized the portrait as a vehicle for communicating evidence of Lincoln’s moral character. In their arguments about the photograph, they relied upon this social knowledge about photography and portraiture and exhibited their comfort with “scientific” discourses of character such as physiognomy and phrenology. Yet the character revealed by photography was not understood only in an individual sense. By means of photographic study of the character of men of weight (to paraphrase Halloran) one might learn something about the community’s character as well. Viewers of the McClure’s Lincoln mobilized their responses to the photograph in ways that elaborated an ideal national type at a time when elites were consumed by anxiety about the fate of “American” identity. Through their close readings of the photograph, Lincoln the man became what Carl Sandburg marvelously termed the “national head.” In framing Lincoln not only as the moral “savior of the Union” but also as the “first American,” viewers used the McClure’s Lincoln as a rhetorical resource for working out the anxieties of their age.

The McClure’s Lincoln

McClure’s published the daguerreotype to accompany the first in a series of articles on the life of Abraham Lincoln penned by Ida Tarbell.15 Tarbell is best known today as the Progressive Era muckraking journalist who exposed corporate corruption at the Standard Oil Company.16 Like many of her post–Civil War generation, Tarbell had a passing fascination with Lincoln; one of her most vivid childhood memories was witnessing her parents’ grief upon his death.17 For the foundation for her life of Lincoln Tarbell relied on the biographers who had known him most intimately.18 But the selling point for Tarbell’s series was that she went beyond the familiar tales. In her initial efforts she was frustrated by Lincoln’s former secretary (and, later, fellow biographer) John Nicolay, who told her that her work was fruitless; there was “‘nothing of importance’ left to be printed on Lincoln’s life.”19 Despite Nicolay’s dismissiveness, Tarbell’s series did in fact deliver new facts, documents, and images in an era when people had begun to share Nicolay’s conclusion that Lincoln’s full story had already been told. She traveled to Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois, interviewing people who had known Lincoln in person and consulting court records, newspapers, and other archival resources that previous Lincoln biographers had neglected. Such legwork “cast a much brighter light upon Lincoln’s parentage, childhood, and youth.”20 Judith Rice argues that Tarbell’s series “marked a shift in the historiography of Lincoln literature” by depicting Lincoln’s early life on the frontier in a positive light. Earlier biographers had “belittled the frontier environment in their works”; Lincoln’s former law partner William Herndon, for example, had suggested that Lincoln came of age in “a ‘stagnant, putrid pool.’”21 Tarbell, by contrast, “emphasized the frontier as encouraging traits that led to [Lincoln’s] success.”22 As we shall see, her emphasis on how the “ennobling” qualities of the frontier shaped Lincoln paralleled some viewers’ responses to the daguerreotype.23

For McClure’s, a middlebrow literary magazine barely three years old, the Tarbell series would pave the way to its early success. Publisher S. S. (Samuel Sidney) McClure founded the magazine in 1893 in the belief that a cheaper illustrated literary magazine could succeed.24 Seeing a gap between the working-class populism of People’s Literary Companion and the higher-end elitism of periodicals like Century, Harper’s, and Scribner’s, Sam McClure sought to create an affordable mainstream periodical that was squarely positioned for the middle-class reader.25 During college breaks McClure had worked as a traveling salesman; he noted in his autobiography that “the peddling experiences of those three summers had given me a very close acquaintance with the people of the small towns and the farming communities, the people who afterward bought McClure’s Magazine.”26 McClure’s desire to combine illustration with low cost was made easier by technical developments in image reproduction. The halftone process had been in what Ulrich Keller terms “experimental” use “since 1867 in weekly magazines and since 1880 in daily papers.”27 After some technical improvements, by the early 1890s it was in wide use by large newspapers and magazines.28 Combined with the availability of cheaper glazed paper, halftone made it possible for publishers like McClure to provide an inexpensive yet lavishly illustrated product.29

McClure shared with Tarbell a deep interest in Lincoln; she noted that Lincoln “was one of Mr. McClure’s steady enthusiasms.”30 Like Lincoln, McClure was a Westerner. Born in Ireland, McClure spent his formative years in the Midwest and graduated from Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois, in 1882.31 In 1858 Knox was the site of the fifth Lincoln-Douglas debate; the campus still resonated with the memory of Lincoln when McClure was a student there twenty-five years later. Founded in the evangelical tradition and (legend has it) in a town with a stop on the Underground Railroad, Knox College encouraged students to be pious and embrace moral and political causes of the day, from temperance to abolition and woman suffrage.32 Whether it was because of Lincoln’s well-established popularity as a subject, or Sam McClure’s longtime interest in Lincoln, or both, McClure’s magazine featured Lincoln prominently: in its first ten years alone the magazine published thirty articles on Lincoln.33

McClure’s promised of its Lincoln series, “We shall publish fully twice as many portraits of Lincoln as have ever appeared in any Life, and we shall illustrate the scenes of Lincoln’s career on a scale never before attempted.”34 Between its first issue, in 1893, and the first installment of Tarbell’s Lincoln series, in November 1895, the circulation of the magazine rose steadily from eight thousand to more than one hundred thousand readers per month, enabling it to compete with publications such as Century and Scribner’s.35 Sam McClure sought to raise sales even further by making a heavily publicized splash with one of the most vivid Tarbell discoveries: a previously unpublished photograph of the late president that had been made when he was a much younger man.

During the course of her research Tarbell met Robert Todd Lincoln, the only surviving child of the president. Robert Lincoln jealously guarded his father’s legacy and famously battled with Lincoln’s biographers. He did not provide Tarbell with much (his personal papers, which included a wealth of hitherto unknown information related to his father, were not made available to researchers until 1947), but he did show her a daguerreotype that he said was the earliest known photograph of his father.36 Tarbell was shocked at what she saw. The photograph looked like Lincoln, but one the public had never seen before. Previously known photographs of Lincoln dated only as far back as the late 1850s, well into Lincoln’s public career and middle age. The most famous of these early images was made by photographer Alexander Hesler in 1857. Known as the “tousled hair” portrait, it portrayed a strong but rather disheveled Lincoln.37 This new yet older image would allow McClure’s readers to encounter Lincoln as a much younger and more dignified-looking man. While the 1857 “tousled hair” photograph figured Lincoln as a raw frontier lawyer having what can only be described as a bad hair day, this new image showed a youthful, dignified, reserved Lincoln. Tarbell recalled, “It was another Lincoln, and one that took me by storm.”38

Access to the daguerreotype was quite a coup. McClure decided the image should be published as the frontispiece of Tarbell’s first installment in November 1895. The magazine proudly (if convolutedly) trumpeted its find: “How Lincoln Looked When Young Can be learned by this generation for the first time from the only early portrait of Lincoln in existence, a daguerreotype owned by the Hon. Robert T. Lincoln and now first published, showing Lincoln as he appeared before his face had lost its youthful aspect.”39 While forgery of Lincolniana was common by the 1890s, this image was not a fake; coming from Lincoln’s own son, readers would not doubt its authenticity.40 McClure promoted the photograph for all it was worth.

The image is a cropped version of a quarter-plate, three-quarter-length-view daguerreotype most likely made in the mid to late 1840s. The McClure’s version isolates Lincoln’s head and shoulders and frames him in the rather fuzzy pictorialist haze that was common to magazine reproductions of portraits in the 1890s. Yet editors also used an elaborate Victorian line drawing to frame the image, perhaps attempting to signal to viewers its daguerreian origins. The differences between the two images should be of interest, for 1890s viewers were not only encountering an 1840s photograph, but they were also encountering it framed in a decidedly 1890s fashion.

To be specific, what McClure’s readers encountered in the pages of the magazine was a halftone reproduction of a photograph of a daguerreotype. Most photographic reproductions of images, especially photographic reproductions of photographs, are viewed simply as transparent vehicles for communication of the earlier image. But Barbara Savedoff warns against the assumption of transparency: “We are encouraged to treat reproductions as more or less transparent documents. But of course, photographic reproductions are not really transparent. They transform the artworks they present.”41 Daguerreotypes, in particular, are dramatically transformed in the process of reproduction.42 The daguerreotype process “produced a direct, camera-made positive, no negative was available for later printing.” As a result, daguerreotypes were not reproducible but rather retained an aura of authenticity. As Richard Benson puts it, “Every daguerreotype is a unique object that once sat in the camera facing the subject of the picture.”43 In addition, the mirrored daguerreotype is meant to be engaged directly and intimately by the individual viewer, literally manipulated by hand in order for the image to come into view.44 Photographic reproductions of daguerreotypes thus lose both their magical mirrored quality as well as the visual depth of the original.45 The McClure’s reproduction of Lincoln by necessity removed the image from its association with daguerreotypy (despite the editors’ attempt to “frame” it) and transformed it into an image that was more familiar to late nineteenth-century magazine readers. McClure’s viewers’ experiences of the photograph were thus several steps removed from an encounter with the “magical” aura of the Lincoln daguerreotype. This conceptual distance makes viewers’ effusive responses to the image initially all the more surprising. What exactly was it about the photograph—no longer a magical daguerreotype, but a run-of-the-mill halftone magazine illustration—that produced such passionate rhetoric? As we shall see, the image’s potency had a lot to do with cultural understandings of what portrait photographs were believed to communicate to viewers in 1895.

“Tousled hair” portrait of Abraham Lincoln. Based on photograph by Alexander Hesler, 1857. Indiana Historical Society, P0406.

Abraham Lincoln, congressman-elect from Illinois. Daguerreotype by Nicolas H. Shepherd, Springfield, Illinois, ca. 1846–1847. Library of Congress.

McClure was right that the photograph would draw immediate attention to Tarbell’s series. Circulation swelled to 175,000 for the first of Tarbell’s articles in the series and then catapulted to 250,000 for the second installment in December.46 McClure later noted that “the years ’95–’96 put McClure’s Magazine on the map”; as a result of Tarbell’s Lincoln series, the magazine’s “prosperity and standing had been established.”47 Circulation numbers were not the only sign of interest in the series. Harold Wilson notes, “More letters on Lincoln arrived than all other editorial correspondence.”48 A number of readers responded specifically to the new daguerreotype. The December 1895 issue featured four pages of letters, the January 1896 issue three more. As noted earlier, McClure’s was intended to be a lower-cost, middle-class magazine of letters, more affordable and “popular” than expensive magazines of the day such as Scribner’s or Harper’s. Yet curiously the majority of letters published in response to the photograph were not from these middle-class readers but from those who represented the era’s intellectual elite: university professors, Supreme Court justices, and former associates of Lincoln.49 Judging from the content of the letters and from the identity of the letter writers, it is likely that McClure sent advance copies of the photograph and its accompanying text to members of the Eastern political and scholarly establishment.50 He probably had several motivations for doing so: to drum up interest in the upcoming Tarbell series, to show his confidence in the authenticity of the image itself by “testing it out” before “experts”—not photography experts but those who were in politics or who had known Lincoln in life—and to solicit elite responses in order to signal to McClure’s readers the “proper” way to interpret the photograph. When I discuss the letters below it is important to keep in mind that those whose responses to the photograph were published in the pages of McClure’s were not necessarily the same readers who would have purchased the magazine on the newsstand or subscribed to it at home. These expert letter writers solved the reading problems posed by the photograph by locating in it resources for making arguments about individual and national character.

“Valuable Evidence as to His Natural Traits . . .”

Overwhelmingly, letters discussed the Lincoln photograph not as a material object of history, nor as an artful example of a technology no longer in use, but in terms of the kind of evidence it offered about its subject. In interpreting the photograph’s significance, writers tapped into culturally available narratives about Lincoln in complex and fascinating ways. The letters are especially striking for the way they negotiate the complex temporality of the photograph. Lincoln had been dead for nearly thirty years, the photograph itself was nearly fifty years old, yet almost to a man the letters were written in the present tense: the image “is Lincoln,” it “explains” Lincoln. The ontology of the photograph permits such a slippage, of course, for via the photograph Lincoln is persistently present despite his absence. Importantly, this temporal ambiguity enables readers to engage the image actively. Rather than simply noting the photograph’s existence as a document of the past, McClure’s readers activated the image in their own present. In doing so they did not assume that the photograph spoke for itself, but—as we saw in the previous chapter’s discussions of war and spirit photography—transformed it into a playful space for interpretation.

For some the question of Lincoln’s physical recognizability posed a reading problem. None of the writers overtly disputed the identity of the photograph as Lincoln, although a few did have trouble seeing a resemblance to the man they remembered from history. The Honorable David J. Brewer, associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, wrote, “The picture, if a likeness, must have been taken many years before I saw him and he became the central figure in our country’s life. Indeed, I find it difficult to see in that face the features with which we are all so familiar.”51 Similarly, Charles Dudley Warner of Hartford had a hard time seeing his recollected Lincoln in the photograph: “The deep-set eyes and mouth belong to the historical Lincoln, and are recognizable as his features when we know that this is a portrait of him. But I confess that I should not have recognized his likeness. . . . The change from the Lincoln of this picture to the Lincoln of national fame is almost radical in character, and decidedly radical in expression.”52 For these letter writers, the Lincoln of history—the man from Springfield—clashed in their imaginations with the Lincoln of memory: the Lincoln of the presidency and “national fame.”

Brewer’s and Warner’s difficulties mirrored Tarbell’s own reported experience of first viewing the photograph—it was radical, a Lincoln no one had seen before. Yet most letter writers reported otherwise. A colleague from Lincoln’s younger years wrote, “This portrait is Lincoln as I knew him best: his sad, dreamy eye, his pensive smile, his sad and delicate face, his pyramidal shoulders, are the characteristics which I best remember; . . . This is the Lincoln of Springfield, Decatur, Jacksonville, and Bloomington.”53 The Honorable Henry B. Brown, associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, noted of the McClure’s Lincoln, “I recognized it at once, though I never saw Mr. Lincoln, and know him only from photographs of him while he was President.” Knowing the subject in life apparently bore no correlation with recognition of the man in the photograph. Brown continued, “From its resemblance to his later pictures I should judge the likeness must be an excellent one.”54 For Brown, as likely for the vast majority of McClure’s readers, recognition of this different, early Lincoln did not require previous acquaintance with Lincoln the man, but with visual knowledge of other images that had circulated in public.

Perhaps concerned about the general tendency to equate virtue and wisdom with beauty, correspondents also dwelled on the pressing questions of Lincoln’s purported ugliness and “vulgarity.” Indeed, the photograph seemed to show a man who was much less physically awkward than many remembered. Henry C. Whitney, identified in the magazine as “an associate of Lincoln’s on the circuit in Illinois,” wrote of the daguerreotype, “It is without doubt authentic and accurate; and dispels the illusion so common (but never shared by me) that Mr. Lincoln was an ugly-looking man.” Whitney continued, emphasizing Lincoln’s distinctive masculinity: “In point of fact, Mr. Lincoln was always a noble-looking—always a highly intellectual looking man—not handsome, but no one of any force ever thought of that. All pictures, as well as the living man, show manliness in its highest tension—this as emphatically as the rest.” Finally, implying perhaps the famed roughness of Lincoln’s frontier habits, Whitney concluded bemusedly, “I never saw him with his hair combed before.”55 Thomas M. Cooley, thematically echoing Tarbell’s interest in dispelling the myth of Lincoln’s vulgar frontier upbringing, observed, “And what particularly pleases me is that there is nothing about the picture to indicate the low vulgarity that some persons who knew Mr. Lincoln in his early career would have us believe belonged to him at that time. The face is very far from being a coarse or brutal or sensuous face.”56

Many of the correspondents in McClure’s noted the absence of “melancholy” in Lincoln’s face, which they took to be a characteristic of his later presidential-era portraits. John C. Ropes of New York City wrote, “It is most assuredly an interesting portrait. The expression, though serious and earnest, is devoid of the sadness which characterizes the later likenesses.”57 Woodrow Wilson, then a professor of finance and political economy at Princeton, noted, “The fine brows and forehead, and the pensive sweetness of the clear eyes, give to the noble face a peculiar charm. There is in the expression the dreaminess of the familiar face without its later sadness.”58 Similarly, Herbert B. Addams, professor of history at Johns Hopkins University wrote, “The portrait indicates the natural character, strength, insight, and humor of the man before the burdens of office and the sins of his people began to weigh upon him.”59

Some readers saw in the photograph shades of Lincoln’s future greatness, a man whose rise to prominence literally was prefigured in his visage. John T. Morse, biographer of Lincoln, Jefferson, and Adams, among others, wrote to the magazine, “I have studied this portrait with very great interest. All the portraits with which we are familiar show us the man as made; this shows us the man in the making; and I think every one will admit that the making of Abraham Lincoln presents a more singular, puzzling, interesting study than the making of any other man known in human history.”60 Morse went on to note that he had shown the portrait to several people without telling them who it was: “Some say, a poet; others, a philosopher, a thinker, like Emerson. These comments also are interesting, for Lincoln had the raw material of both these characters very largely in his composition. . . . This picture, therefore, is valuable evidence as to his natural traits.”61

Themes of character and expression dominate the letter writers’ remarks—specifically, character as revealed in expression. The photograph almost universally is read as a locus of evidence about Lincoln’s character. Lincoln’s face is “noble,” both his eyes and his smile are “pensive.” His brow is “fine” and illuminated with “intellect”; his eyes are read alternately as “clear” and “dreamy.” Several correspondents explicitly compared this early image of Lincoln with ones that were more familiar to them. While later images offered a “sad” Lincoln, this image avoided such melancholy; the younger Lincoln is merely “serious and earnest.” In these accounts Lincoln is alternately a dreamy romantic and a strong patriot, a “pensive” intellectual and an insightful empath, a manly “military chieftain” and a feminized figure of “sweetness” and delicacy. Those writing about the photograph solved the reading problems it posed by constructing Lincoln as a man for all people. Regardless of the emotional valence of their readings, letter writers grounded their claims about the photograph in the assumption that there was a direct correspondence between Lincoln’s image and his “natural traits”—between, as General Walker so tellingly put it, “Mr. Lincoln’s face and his mind and character.” In making such arguments McClure’s readers activated their social knowledge of the relationship between photographic portraiture and popular nineteenth-century discourses of physiognomy and phrenology. Such implicit but powerful habits of viewing enabled them to read Lincoln’s face and, oscillating between individual and communal conceptions of character, identify it as the face of the nation.

The Photographic Portrait as an Index of Character

Portraits in the nineteenth century were thought to reveal or “bring before the eyes” something vital and almost mysterious about their subjects.62 It was assumed that the photographic portrait, in particular, did not merely “illustrate” a person but also constituted an important locus of information about human character. Unlike the painted portrait, which would theoretically be created to “flatter,” the photographic portrait was perceived as a more reliable index of character.63 By mid century “the standard for a truly accurate likeness had become not merely to reproduce the subject’s physical characteristics but to express the inner character as well.”64 Even after changes in photographic technology after the Civil War enabled more spontaneous images, the prevailing rhetoric of photography preferred a more formal style of portraiture that was thought to say something more general about human nature and society. David M. Lubin hints at the oscillating qualities of character when he observes, “Even though a portrait purports to allow us the close observation of a single, localized, individual, we discern meaning in it to the extent that it appears to reveal something about general human traits and social relationships.”65

As loci of generalizable information about character, portraits educated viewers about the virtues of the elites and warned them against the danger of vice; thus they served as a way of educating the masses about what it meant to be a virtuous citizen. Images such as the large daguerreotypes made by Mathew Brady in his New York and Washington, D.C., studios at mid century provided visitors not only with an afternoon’s stroll and entertainment but with “models for emulation.”66 Brady’s galleries functioned as citizenship training of a sort, offering a democratic space for viewing a democratic art that paradoxically perpetuated elitist definitions of virtue: “Viewing portraits of the nation’s elite could provide moral edification for all its citizens who needed to learn how to present themselves as good Americans in a quest for upward mobility.”67 Of Brady’s gallery Alan Trachtenberg writes, “With its irresistibly compelling pictures of presidents, governors, poets, and preachers, ‘Lecturers, Lions, Ladies and Learned Men,’ the gallery served as a ‘paragon of character.’”68 Gallery of Illustrious Americans, a book featuring exquisite lithographs made from the Brady studio’s daguerreotypes of national luminaries, constructed the story of national destiny by offering the reading and viewing public “a space for viewing men in the guise of republican virtue: gravitas, dignitas, fides.”69

Late nineteenth-century portraits often combined these traditional assumptions with modern production techniques. Consider, for example, a pair of wedding portraits featuring my great-grandparents Louisa and Lewis W. Chase. The photographs likely were made in 1887 in Kilbourne City, Wisconsin, to commemorate the couple’s marriage. Relatively standard late nineteenth-century head-and-shoulders views, the photographs are neither remarkable nor all that different from the McClure’s representation of Lincoln. The Chases wear the well-made, fashionable attire of the rising classes along with the serious expressions demanded for portraits commemorating so auspicious an occasion. They appear to be middle-class and comfortable, “good citizens” likely well positioned in local society. Yet we most certainly understand the portraits differently if we know that the photographs are manipulated. In a process called “overpainting,” the young couple’s photographic portraits were superimposed on other, better-dressed bodies to create a hybrid that was common to photographic portraiture of the period.70 Such photographic manipulation enabled the couple to project an image of themselves as they wanted to be rather than as they were. Embedded in a visual culture imbued with this complex rhetoric of the photographic portrait, the Chases implicitly would have understood the importance and the social necessity of such “manipulation.” Yoking the available technologies of their own time to long-held beliefs about the relationship between photographic portraiture and human character, the Chases were able to accomplish visually what they would accomplish literally only many years later.71

Visual discourses of morality did not just emphasize the aspirations of the virtuous civic elite, however. As Allan Sekula reminds us, historians need to chart both the “honorific and repressive poles of portrait practice” if they are to understand the role of portrait photography in the nineteenth century.72 Just a few years after photography appeared, the portrait was already being used for the purposes of criminal identification and classification.73 Curiously, most traditional histories of photography ignore crime and police photography altogether, despite its social and political importance throughout the nineteenth century.74 Yet even in the earliest years of photography, for every bourgeois portrait there could always be found a “lurking, objectifying inverse in the archives of the police.”75 By 1840 police departments already were using photography to identify and categorize crime suspects. By the early 1850s the mug shot was a standardized genre that could be taught to police photographers.76 In the late 1850s “Rogues’ Galleries” began to appear in the urban centers of the United States and Western Europe, in which the faces of known criminals were put forth in a kind of “municipal portrait show” displayed in police headquarters to help solve and prevent crime.77 Mug shots were not only products of a visual order of surveillance but also served simultaneously as elements of spectacle and moral education.78

Such education was possible because of the connection between portrait photography and “scientific” discourses such as phrenology and physiognomy, which connected physical attributes to moral character and intellectual capacities. Sekula argues, “We understand the culture of the photographic portrait only dimly if we fail to recognize the enormous prestige and popularity of a general physiognomic paradigm in the 1840s and 1850s.”79 Throughout the nineteenth century, “the practice of reading faces” was a key part of everyday life and remained so well into the early twentieth century.80 Whether it was images like Brady’s Gallery of Illustrious Americans or those of the Rogues’ Galleries, Americans were accustomed not only to reading the faces in photographs but to making judgments about the moral character of their subjects as well. As we have already seen, viewers of the Lincoln photograph in McClure’s paid close attention to the face, arguing that Lincoln’s face was the key to understanding his character. If we are to understand these readings, we need to trace how the portrait photograph circulated in a fin-de-siècle visual culture heavily influenced by the discourses of physiognomy.

Louisa and Lewis Chase, overpainted wedding portraits, ca. 1887. Unknown photographer, Wisconsin. Collection of Finnegan family.

Hermeneutics of the Face: Phrenology and Physiognomy

Scholars have documented extensively the nineteenth century’s commitment to the formation of character as well as the popularity and prevalence of the “sciences” of phrenology and physiognomy. Karen Halttunen argues that during the bulk of the nineteenth century character formation was incredibly important to middle-class Americans, “the nineteenth-century version of the Protestant work ethic.”81 Antebellum Americans, in particular, “asserted that all aspects of manner and appearance were visible outward signs of inner moral qualities.” “Most importantly,” Halttunen observes, “a man’s inner character was believed to be imprinted upon his face and thus visible to anyone who understood the moral language of physiognomy.”82 The popular prominence of this language coincided with the birth of photography in the United States and Europe. Sekula notes, “Especially in the United States, the proliferation of photography and that of phrenology were quite coincident.”83 The first volume of the American Phrenological Journal (produced by the Fowler brothers, Lorenzo and Orson, who popularized phrenology in the United States), was published in 1839, the same year the daguerreotype was introduced to the public.84 While phrenology and physiognomy predate photography by many years, the introduction of photography gave them modern relevance and vigor.85

Phrenology and physiognomy, which Allan Sekula calls “two tightly entwined branches” of the so-called moral sciences, were concerned with the knowledge of the internal through observation of the external.86 Conceived in the late eighteenth century by Johann Caspar Lavater and popularized in the United States and Europe in the nineteenth century, physiognomy involved paying attention to “the minuteness and the particularity” of physical details and making analogies between those details and the character traits they were said to illustrate.87 Physiognomy was framed as a science of reading character “in which an equation is posited between facial type and the moral and personal qualities of the individual.”88 Similarly, phrenology was founded upon the belief that “there was an observable concomitance between man’s mind—his talents, disposition, and character—and the shape of his head. To ascertain the former, one need only examine the latter.”89 Both “sciences” were, as Stephen John Hartnett observes, “essentially hermeneutic activities.”90 These interpretive practices “fostered a wide-ranging ‘self-help’ industry that . . . blanketed the nation with magazines and manifestoes intended to guide confused Americans through the multiple minefields of their rapidly changing culture.”91 Employing a circular rhetoric, both practices “drew on the moral and social language of the day in order to guarantee the claims made about human nature.”92 While they could be harmless and entertaining, the practices of phrenology and physiognomy were not simple parlor game fun; indeed, not many more steps were necessary for a full-blown discourse of eugenics.93 These sciences of moral character enabled anxious Americans, especially those of the middle and upper classes, to use a language that placed themselves (as well as marginalized others) in “proper relation.”

Samuel R. Wells, a protégé (and brother-in-law) of the Fowler brothers, ran the publishing operation that helped to popularize their work. Wells believed that physiognomy, phrenology, and physiology constituted a tripartite “science of man.”94 Beginning in the 1860s, Wells wrote and published several books on physiognomy, including New Physiognomy; or, Signs of Character, as Manifested through Temperament and External Forms, and Especially in “The Human Face Divine” and the first of several volumes of How to Read Character: A Handbook of Physiology, Phrenology, and Physiognomy, Illustrated with a Descriptive Chart. Wells’s primary argument in both texts was that while the brain “measures the absolute power of the mind,” the face may be understood as “an index of its habitual activity.”95 Such claims echo ancient notions of ethos as habit or located within the habitual.96 The books outline in exquisite detail how to read faces in order to ascertain temperament and character. There are chapters on every facial feature, including mouth, eyes, jaw, chin, and nose, as well as sections on hands and feet, neck and shoulders, movement, and even palmistry and handwriting analysis. For example, chapter 12, “All About Noses—With Illustrations,” observes that the nose “tells the story of its wearer’s rank and condition.”97 Describing two illustrations of Irish girls, one the “daughter of a noble house,” the other “the offspring of some low ‘bog trotter,’” Wells writes, “The one is elegant, refined, and beautiful; the other, gross, rude, and ugly. The one is fully symmetrically developed, the other is developed only in the direction of deformity.” (No need for the reader to guess which is which.) Noses are not only individual, however; they are also national: “The more cultivated and advanced the race, the finer the nose.”98 The American nose, Wells explains, is an evolved nose that “agrees with our national character and national history.”99

Phrenologists like Wells and Fowler were especially interested in exploring American character. In an 1869 essay published in the American Phrenological Journal, author D. H. Jacques lamented a recent magazine article that had criticized American faces as “‘wholly devoid of poetry, of sentiment, of tenderness, of imagination.’”100 Jacques disputed some specifics of this critique, but then observed, “We are too young as a nation to have fully developed and matured a national type of face; but we have it in process of formation, and the true physiognomist can see that it is destined to be one of the noblest that the world has produced.”101 Such rhetoric tied a hermeneutic of the face to broader conversations about national moral character and illustrated Americans’ increased interest in the nature of American national identity. As we shall see, Lincoln’s image played a large role in conversations about the “national face.”

Of the cultural impact of this implicit physiognomic language, Madeleine Stern observes, “Often without knowing precisely what they were saying, people spoke phrenology in the 1860s as they would speak psychiatry in the 1930s and existentialism in the 1960s.”102 The practice of reading faces lasted well into the early twentieth century (and has never left us), guided by implicit but powerful assumptions about the relationship between appearance and character.103 Perhaps nothing better sums up the ubiquity of such social knowledge than this rhetorical question of an anonymous writer in a 1909 issue of the Methodist Review: “The natural and customary use of language is to express one’s thoughts, and, equally, the habit of the face is to reveal the spirit. The face no index to a man’s nature, no indication of what may be expected from him? As well say that the appearance of the sky is no criterion of the weather. Everybody knows better.”104 “Knowing better” than to discount the “habit of the face,” late nineteenth-century Americans understood the sciences of moral character as readily available rhetorical resources for arguing about human nature and American national identity. They knew, and they could count on others knowing, that “the general rule is that countenance and character correspond.”105

“I think we can see in this face . . .”

Turning back now to the Lincoln letters, we may see how the McClure’s letter writers addressed the reading problems posed by the photograph by recognizing photography’s capacity to communicate character and mobilizing their social knowledge of the “hermeneutics of the face.” The writers assume that the photograph’s links to Lincoln’s character are obvious; no one needs to make the case for reading Lincoln’s face. The question for them is not whether the photograph shows a relationship between character and expression, but what specifically that relationship is. Descriptions of Lincoln’s eyes as being “clear,” for example, or his smile being “pensive,” are characterological references that would resonate for viewers familiar with physiognomic discourse. Perhaps the most vivid example may be found in the letter of Thomas M. Cooley of Ann Arbor, Michigan, former chief justice of the Supreme Court of Michigan, who began, “I think it a charming likeness; more attractive than any other I have seen, principally perhaps because of the age at which it was taken. The same characteristics are seen in it which are found in all subsequent likenesses—the same pleasant and kindly eyes, through which you feel, as you look into them, that you are looking into a great heart. The same just purposes are also there; and, as I think, the same unflinching determination to pursue to final success the course once deliberately entered upon.”106 Thus far Cooley’s reading is similar to other correspondents’ interpretations in its attention to physiognomic detail. Cooley, like other letter writers, claims to recognize much about Lincoln. His face reveals not only “pleasant and kindly eyes,” but these eyes in fact signal a “great heart.” His expression reveals “just purposes,” as well as “unflinching determination.” Here is a man, Cooley suggests, who can be relied upon to make the right decisions, a man who is thoughtful, determined, kind. Note, too, how the continuity of Lincoln is emphasized. Despite his youth in the photograph, Cooley emphasizes similarities to the Lincoln of today: the “same characteristics” are in later likenesses, including the “same” eyes; these eyes further point to the “same just purposes” and “the same unflinching determination.” What the photograph reveals about Lincoln’s ethos is its stability, its consistency.

The physiognomic frame thus mobilized to reveal Lincoln’s stability and consistency, Cooley then goes on to elaborate in detail what specifically the photograph reveals about Lincoln’s character. Transcending temporal boundaries in a way that only photographic interpretation can, Cooley reads the photograph in the present while speculating about a future that is already past. He constructs the meaning of the image in the conditional tense even though from his point of view fifty years later there is no uncertainty:

It seems almost impossible to conceive of this as the face of a man to be at the head of affairs when one of the greatest wars known to history was in progress, and who could push unflinchingly the measures necessary to bring that war to a successful end. Had it been merely a war of conquest, I think we can see in this face qualities that would have been entirely inconsistent with such a course, and that would have rendered it to this man wholly impossible. It is not the face of a bloodthirsty man, or of a man ambitious to be successful as a mere ruler of men; but if a war should come involving issues of the very highest importance to our common humanity, and that appealed from the oppression and degradation of the human race to the higher instincts of our nature, we almost feel, as we look at this youthful picture of the great leader, that we can see in it as plainly as we saw in his administration of the government when it came to his hands that here was likely to be neither flinching nor shadow or turning until success should come.107

This passage is extraordinary for the way it oscillates between the specifics of the image and imaginative conclusions about Lincoln’s character and behavior. The face that Cooley has read for us is not the face of someone who is “bloodthirsty” or desirous of power; rather, this is the face of a man who will unflinchingly pursue a course of deliberate action. However (note the conditional tense), if a war should come (an echo of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural: “and the war came”), then we can be assured that this man would go to war only for the right reasons; indeed, his face signals a character for which doing otherwise would be patently “impossible.” This is not the face of a power-hungry, bloodthirsty “ruler of men,” but of a benevolent, thoughtful, decisive leader: Lincoln, Savior of the Union.

Strikingly, Cooley goes a step beyond analysis of Lincoln’s character to make quite another argument altogether: he actually argues that the war was not a war of conquest precisely because the photograph does not reveal a man with such impulses: “I think we can see in this face qualities that would have been entirely inconsistent with such a course.”108 Cooley not only uses the photograph to articulate a vision of Lincoln as the Savior of the Union, but he also mobilizes it in the service of arguments about the nature of the war itself. To “recognize” Lincoln’s character in his face, then, is to imagine that the portrait photograph has the capacity to visualize moral claims.

Cooley is not alone in reading Lincoln’s image in this way. Lincoln was the favored subject of physiognomists such as Samuel Wells. Wells’s discussion of an engraved reproduction of a Lincoln photograph amounts to a near-complete physiognomic study of Lincoln and prefigures Cooley’s own remarks nearly thirty years later:

This photograph of 1860 shows, not the face of a great man, but of one whose elements were so molded that stormy and eventful times might easily stamp him with the seal of greatness. . . . The brow in the picture of 1860 is ample but smooth, and has no look of having grappled with vast difficult and complex political problems; the eyebrows are uniformly arched; the nose straight; the hair careless and inexpressive; the mouth, large, good natured, full of charity for all . . . but looking out from his deep-set and expressive eyes is an intellectual glance in the last degree clear and penetrating, and a soul whiter than is often found among the crowds of active and prominent wrestlers upon the arena of public life, and far more conscious than most public men of its final accountability at the great tribunal.109

Reading the past of the Civil War into the present of the picture, Wells, like Cooley, uses the discourse of physiognomy to predict the future: this man with the “white soul” is destined for greatness in the face of heavy burdens. Lest the reader of New Physiognomy be unclear about the implications of his reading, Wells sums up: “The lesson . . . is one of morals as well as of physiognomy. Let any one meet the questions of his time as Mr. Lincoln met those of his, and bring to bear upon them his best faculties with the same conscientious fidelity that governed the Martyr-President, and he may be sure that the golden legend will be there in his features.”110 These ways of reading Lincoln persisted over time. As late as 1909 (the year of the Lincoln centenary) phrenological journals echoed Wells’s earlier analysis of Lincoln’s body, face, and character: “He was thus a true, sympathetic, tender-hearted, yet firm and positive man, and through his basilar faculties, which were actively developed, he manifested tragedic force, energy, and executive power.”111

While neither Cooley nor the other correspondents in McClure’s wrote of Lincoln with the precise detail found in physiognomic accounts, they still spoke in a language of moral pseudo-science that offered a potent framework for reading portraits. Those who read the photograph mobilized physiognomic recognition not only to honor Lincoln’s individual ethos but also to proclaim him as a new “American type” in an age of anxiety about the fate of white national identity. In doing so, they found in the photograph rhetorical resources for a more communal sense of character as well, a national character constituted as the dwelling place of “the heritage of our shared appearances.”112

“A new and interesting character”: Lincoln as the National Head

Lincoln’s physical appearance was a hugely popular topic in the Gilded Age. In the years following Lincoln’s assassination, for example, Lincoln’s law partner William Herndon gave a series of popular lectures on Lincoln. The first of these, delivered in two parts in Springfield, Illinois, on December 12 and 27, 1865, was titled “Analysis of the Character of Abraham Lincoln.” Herndon began his study of Lincoln by observing, “Before I enter into an analysis of the mind—the character of Mr. Lincoln[—]it becomes necessary first to hold up before your minds the subject of analysis—the subject of such anatomy.”113 Following physiognomic convention, Herndon began with a detailed discussion of “the subject’s” physical appearance, mentioning everything from Lincoln’s hat size to his gait to the “lone mole on the right cheek.”114 Of the physical Lincoln Herndon observed, “His structure—his build was loose and leathery. . . . The whole man—body & mind worked slowly—creekingly [sic], as if it wanted oiling.”115 Only after this physical examination did Herndon turn to topics such as Lincoln’s “perceptiveness,” his “suggestiveness,” his “judgments,” and his “conscience.” The arrangement of the speech suggests Herndon implicitly understood that one must explore the subject’s countenance before engaging the subject’s character.

Popular magazines frequently printed personal recollections from those who had known Lincoln in life, “expert” commentary on Lincoln’s appearance, or stories recounting the making of Lincoln photographs, life masks, or sculptures.116 Writers sought to construct their preferred image of Lincoln in the public mind; in doing so, many of them tied that image to broader questions about the nature of American national identity at the turn of the twentieth century. In 1891 John G. Nicolay, Lincoln’s former private secretary, published an essay in Century magazine called “Lincoln’s Personal Appearance.” Nicolay’s stated goal in the essay was to dispel the persistent myth of Lincoln’s ugliness.117 Yet Nicolay was also interested in framing Lincoln as a new, distinctively “American” type. To accomplish this he quoted accounts that relied heavily on the kind of physiognomic detail we already have seen. Writing of his experience making a bust of Lincoln, sculptor Thomas D. Jones recalled in Nicolay’s article that Lincoln’s “great strength and height were well calculated to make him a peerless antagonist. . . . His head was neither Greek nor Roman, nor Celt, for his upper lip was too short for that, or a Low German. There are few such men in the world; where they came from originally is not positively known.”118 Nicolay constructed Lincoln as distinctly American, so much so that his ancestry was unimportant. Lincoln’s American-ness could be found, Nicolay contended, in the frontier upbringing that gave him exposure to different kinds of people and situations: “It was this thirty years of life among the people that made and kept him a man of the people—which gave him the characteristics expressed in Lowell’s poem: New birth of our new soil; the first American.”119 Merrill D. Peterson observes that the discourse highlighting Lincoln as the first American “radiated everywhere” after the Civil War: “[James Russell] Lowell had discerned the archetype of a new national character, one long imagined but only now realized in a man who looked at things, who related to people, who bore himself in ways indigenous to the American continent.”120 The sheer reach of the trope of the first American may perhaps best be illustrated by its appearance in Southern discourse after the war. Even Henry Grady, in his conciliatory 1886 oration “The New South,” spoke of Lincoln as “greater than Puritan, greater than Cavalier,” describing him as the “first typical American” and noting that “in his homely form were first gathered the vast and thrilling forces of his ideal government.”121

Viewers of the photograph in McClure’s made similar arguments about Lincoln as the first American. Letter writers argued that the Lincoln photograph revealed him as a distinctly American type, a “new man” whose physiognomy indicated a new stage in American characterological development. One of those who wrote to McClure’s in response to the photograph was Truman H. (T. H.) Bartlett, identified by editors as an “eminent sculptor, who has for many years collected portraits of Lincoln, and has made a scientific study of Lincoln’s physiognomy.”122 In his letter to McClure’s, Bartlett observes that the photograph suggested the rise of a “new man”: “It may to many suggest other heads, but a short study of it establishes its distinctive originality in every respect. It’s priceless, every way, and copies of it ought to be in the gladsome possession of every lover of Lincoln. Handsome is not enough—it’s great—not only of a great man, but the first picture representing the only new physiognomy of which we have any correct knowledge contributed by the New World to the ethnographic consideration of mankind.”123 Setting aside Bartlett’s tortured prose, we see that for Bartlett (as for Nicolay), Lincoln’s physical features signaled a marked shift in the moral makeup of American man. While some might be content to tie the image to other physiognomic types (“other heads,” as Bartlett so wonderfully puts it), Bartlett suggests that the “distinctive originality” of Lincoln’s features signaled something entirely new. Twelve years later Bartlett published in McClure’s the study to which editors had alluded.124 In “The Physiognomy of Lincoln,” a highly detailed analysis of photographs and life masks of Lincoln’s face and hands, Bartlett elaborated how Lincoln’s physiognomy represented a distinct departure from those “other heads.” Analyzing both facial expressions and bodily movement, Bartlett contended that both proved Lincoln was a new American type. The sculptor claimed to have shown the life masks and photographs to famous sculptors in France, including Auguste Rodin, who agreed with Bartlett that they illustrated “‘a new and interesting character. . . . If it belongs to any type, and we know of none such, it must be a wonderful specimen of that type.’ . . . ‘It is a new man; he has tremendous character,’ they said.’”125 In all of these texts Lincoln is constituted not only in terms of his individual moral character but also in terms of his representativeness of a “new” kind of American character: “The utter individuality of Lincoln, which had impressed all who knew him, entered into the definition of his Americanness, to the point that his physiognomy blended into the representation of Uncle Sam.”126

Such statements necessarily lead one to ask why it was so vital for McClure’s readers—especially the elite letter writers—to connect Lincoln to this “new,” uniquely American ideal. Why care about character in this communal, national, shared sense? Their desire can in large part be traced to racial and class anxieties about the changing character of American identity at the end of the nineteenth century. I noted earlier that the majority of the letter writers were elite men—lawyers, judges, journalists, professors, and former acquaintances of Lincoln. Such professionals likely had a particular interest in specific ways of recognizing Lincoln. Elites existed in a perpetual state of anxiety during the Gilded Age. Many reasons have been posited for this cultural “neurasthenia,”127 one of which was confusion about what it meant to be an American. Alan Trachtenberg writes that “America” was “a word whose meaning became the focus of controversy and struggle during an age in which the horrors of civil war remained vivid.”128 Robert Wiebe suggests that this struggle constituted nothing less than a national identity crisis: “The setting had altered beyond their [elites’] power to understand it and within an alien context they had lost themselves. In a democratic society who was master and who servant? In a land of opportunity what was success? In a Christian nation what were the rules and who kept them? The apparent leaders were as much adrift as their followers.”129 Attempts to grapple with these questions led white elites to define American identity by emphasizing both what Americans were and what they were not.

The white American cultural elite (I would put the McClure’s letter writers in this category) believed they had good cause to be worried about the future of American identity. During these years the United States passed through a violent period of labor unrest, including most prominently the Haymarket events of 1886 and the bloody Pullman Strike of 1894. The voices of immigrants made themselves increasingly heard in these powerful labor movements, producing real fears of a violent class revolution. As T. J. Jackson Lears observes, “Worry about . . . destruction by an unleashed rabble, always a component of republican tradition, intensified in the face of unprecedented labor unrest, waves of strange new immigrants, and glittering industrial fortunes.”130 In the face of rising immigration, fears of miscegenation, and the threats to capital from labor, anxious elites sought rhetorically to dissociate certain citizens from the identity of “American.” After the bombing at Haymarket Square in Chicago, one newspaper editorial pronounced, “‘The enemy forces are not American [but] rag-tag and bob-tail cutthroats of Beelzebub from the Rhine, the Danube, the Vistula and the Elbe.’”131 Jacob Riis’s How the Other Half Lives, published in 1890, visualized similar anxieties. Beginning in the late 1880s Riis made photographs of New York’s poor and their living conditions in the city’s ghettos, sharing them in lantern slide lectures delivered to upper-class New York City audiences.132 Writing of the cultural makeup of the New York tenements, Riis observed, “There was not a native-born individual in the court. . . . One may find for the asking an Italian, a German, a French, African, Spanish, Bohemian, Russian, Scandinavian, Jewish, and Chinese colony. . . . The one thing you shall vainly ask for in the chief city of America is a distinctively American community. There is none; certainly not among the tenements.”133 The assumption grounding Riis’s remarks is that there is, in fact, a “distinctively American community,” but it is one by definition of which these poor immigrants cannot be a part.

Not surprisingly, these anxieties were also fueled by popular purveyors of the sciences of moral character, which provided a mechanism by which elites could construct a cohesive American identity through exclusion. Wiebe observes, “The most elaborate method—a compound of biology, pseudo-science, and hyperactive imaginations—divided the people of the world by race and located each group along a value scale according to its distinctive, inherent characteristics. . . . Bristling with the language of the laboratory, such doctrines impressed an era so respectful of science. At the same time, they remained loose enough to cover almost any choice of outcasts.”134 Physiognomy was thus well positioned rhetorically to both define those who were “real Americans” and those whose might be dangerous threats to a pure American identity. In New Physiognomy Wells included a lengthy discussion of “The Anglo-American.” Emphasizing Americans’ genetic connections to the Anglo-Saxon, Celtic, and Teutonic “races,” Wells observed that contemporary Americans differed strikingly in temperament and character from their European counterparts: “The American is tall rather than short; has a well-developed frame-work, covered with only moderately full but very dense and wiry muscle; strongly marked if not prominent features; a Greco-Roman nose; rather high cheek-bones; strong jaws; a prominent chin; and a moderately large mouth.”135 As exemplars of this representative illustrious American, Wells offered up Abraham Lincoln and Cornelius Vanderbilt.136

Wells was not alone in arguing for the preservation of an American identity that was distinct from European ancestry. Wiebe notes, “On the surface Americans everywhere arrived at a common, unequivocal conclusion. Europe was old and tired and declining, America young and vigorous and rising. . . . America, on the contrary, joined virtue with youth, moral vision with power, imagination with thrust.”137 During these years, genealogical organizations such as the Daughters of the American Revolution rose in response to perceived threats to “American civilization,” making available “the consolidation of a seemingly stable, embodied, and racialized national identity, one that conflated American borders with Anglo-Saxon bloodlines.”138 Eugenics discourse reached down from the rarified universe of science into the everyday lives of Americans, where it emphasized the importance of retaining a “pure” American identity in the face of the “threat” of the blending of the races. Such rhetoric was often built on physiognomic principles. In “The Illumined Face,” the same essay that equated reading faces with reading the weather, the anonymous author observed that one might conduct a kind of “before and after” experiment with a group of Native American children. “Put a group of Apache boys and girls before the camera,” the author proposed, then “civilize” them with “Christian training” and see the inevitable changes in subsequent photographs: “The gentling of the savage is visibly reported in his face.”139 Even seemingly innocuous genealogical artifacts such as the baby book were developed as a cultural response to anxieties about the loss of American identity. Baby photographs, for example, served “as a testament to ancestry, inheritance, and continuity in family genealogies,” and eugenicist Francis Galton promoted baby books to “‘those who care to forecast the mental and bodily faculties of their children, and to further the science of heredity.’”140

At roughly the same time that McClure’s was publishing letters in response to the Lincoln daguerreotype, W.E.B. Du Bois was beginning field research in Philadelphia, where he was exploring “the condition of the forty thousand or more people of Negro blood now living in the city of Philadelphia.”141 Mia Bay argues that Du Bois’s groundbreaking study, published in 1899 as The Philadelphia Negro, should be understood as part of “a critical tradition of challenges to racism by minority authors.”142 In the 1890s “black racial thought was in flux,” and while Du Bois’s own “ideas about race were fluid in this period,” Bay contends that The Philadelphia Negro marks Du Bois’s turn toward social science as a way to argue against scientific claims about race.143 As a result, though it does not directly critique the so-called sciences of character, its data-driven social science emphasized the structural constraints faced by African Americans, implicitly countering arguments about nature and biology while acknowledging their power. For example, writing of “prejudice against the Negro” in Philadelphia, Du Bois writes, “In the Negro’s mind, color prejudice in Philadelphia is that widespread feeling of dislike for his blood, which keeps him and his children out of decent employment, from certain public conveniences and amusements, from hiring houses in many sections, and, in general, from being recognized as a man.”144 For Du Bois the “feeling of dislike for his blood” had profound consequences, blocking advancement of the race and prohibiting recognition of the African American’s very humanity. When tied up with the hermeneutic of the face and the pseudo-sciences of moral character, dislike for the blood was “scientifically” rationalized to authorize marginalization and exclusion. Thus photography’s recognized capacity to communicate character, in both the individual and communal senses, colluded with such rhetoric to participate in a circular discourse: one identifies groups one wants to marginalize and exclude and then mobilizes the hermeneutic of the face to authorize the marginalization and exclusion.

During this period the need to fortify a usable (white) American national identity came to its apotheosis with the work of historian Frederick Jackson Turner. In 1893 at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Turner posited his highly influential “frontier thesis.” Emphasizing the heroic, masculine traits of westward-moving pioneers, Turner argued that it was on the frontier that Americans had become Americans, forging a unique national identity apart from their European ancestry.145 Alan Trachtenberg observes that the ethos of the frontier offered by Turner provided a coherent reading “of the American past at a time of disunity, of economic depression and labor strife, of immigrant urban workers and impoverished rural farmers challenging a predominantly Anglo-Saxon Protestant economic and social elite.”146 Turner’s embracing of the frontier thus was not objective historical scholarship so much as it was “serviceable according to the needs of politics and culture: the needs of the nation at a moment of crisis.”147 Turner’s frontier thesis gave white elites a narrative that acknowledged the dynamism of American cultural history while at the same time conveniently ignored or vilified difference and multiplicity. As Patricia Nelson Limerick observes, “In casting the frontier as the most important factor informing American character and democracy,” Turner “paid little attention to Indians. [He] stressed the individualism and self-reliance of the pioneer and had correspondingly little to say about federal aid to expansion. . . . Perhaps most consequentially, [he] provided support for models of American exceptionalism by emphasizing the uniqueness of the American frontier experience.”148

In a collection of essays later published together as The Frontier in American History, Turner sought to project “a national character, a type of person fit for the struggles and strategies of an urban future.”149 One of his strategies, not surprisingly, was to invoke the character of Abraham Lincoln as a synecdoche for the nation’s character. Like the physiognomists and those who wrote to McClure’s magazine, Turner found in Lincoln the ideal representative of what he termed “the frontier form.”150 Turner argued that the Midwest frontier’s mixed populations of English, Scotch Irish, and Germans “promoted the formation of a composite nationality for the American people” and fostered an “American intellect.”151 Being raised among such “distinct people” gave Lincoln pioneer traits that he later used to the advantage of the nation.152 The “great American West,” Turner writes, “gave us Abraham Lincoln, whose gaunt frontier form and gnarled, massive hand told of the conflict with the forest, whose grasp of the ax-handle of the pioneer was no firmer than his grasp at the helm of the ship of state as it breasted the seas of civil war.”153 If Lincoln’s “frontier form” represented the frontier character, it did not take Turner too many more steps to link that frontier character to the glories of democracy itself: “It was not without significance that Abraham Lincoln became the very type of American pioneer democracy, the first adequate and elemental demonstration to the world that that democracy could produce a man who belonged to the ages.”154 Again we see Lincoln the first American, here not framed as an individual man of moral character but as a part of the national ethos, the heritage of shared appearances. In the hands of Turner, Lincoln is not just a representative of the American pioneer character; he is the product of democracy itself.

In an introduction to a 1944 book of photographs of Lincoln, Carl Sandburg concluded after reading late nineteenth-century accounts such as these that Lincoln “was a type foreshadowing democracy. The inventive Yankee, the Western frontiersman and pioneer, the Kentuckian of laughter and dreams, had found blend in one man who was the national head.” At precisely the moment of Lincoln’s Turnerian apotheosis, when Americans were being told there existed a uniquely American identity, this identity was declared to be threatened by the forces of social disorder and the closing of the frontier. The race- and class-infused physiognomic rhetoric constructing Lincoln as the national head—and thus the national ethos—dramatically reflected this tragic frame. Ironically, the Lincoln daguerreotype—no longer a mirror image itself—reflected these anxieties back at viewers. Those who responded to the photograph in McClure’s recognized in that reflection a man whose high moral character and apparently “American” genes fulfilled their need for a “distinctive” American type that was capable of mitigating the anxieties of their age. In such accounts of Lincoln, Sandburg observed, “was the feel of something vague that ran deep in American hearts, that hovered close to a vision for which men would fight, struggle, and die, a grand tough blurred chance that Lincoln might be leading them toward something greater than they could have believed might come true.”155

Reproducing, Recognizing, and Imagining Lincoln

In the 1917 epigraph with which I began this chapter, an author known only as “E.S.M.” observes, “People take awful liberties with Lincoln. . . . It almost makes you wish that Lincoln had been copyrighted.”156 The title of E.S.M.’s essay is “Reproducing Lincoln.” The writer wryly alludes to the frustrating impossibility of fixing Lincoln, of rhetorically managing him in ways that secure his cultural meanings within safe, familiar boundaries. Springfield’s N. H. Shepherd might fix an image of a young lawyer onto a plate, but that image would have the capacity, fifty years later, to exceed the boundaries of its reproduction in ways that were likely unimaginable to the image’s creator or its subject. The responses to the McClure’s Lincoln enable us to explore how late nineteenth-century viewers fixed Lincoln for their own purposes and in light of the concerns of their own interpretive communities. Recognizing in portrait photography resources for the production of arguments about individual and national character, the McClure’s letter writers performed contemporary tensions about the nature of America and Americans, the uniqueness of national character, and the boundaries of national morality. While these choices might seem to be taking “awful liberties,” perhaps they might more properly be termed “fair use.” Alan Trachtenberg observes of Lincoln, “The most famous photographed face in American history may be the most overdetermined, the easiest, and at the same time, the most difficult to read as a person. The images are saturated with history. . . . Our readings depend on larger stories we tell (or hear) about the man and his history.”157 The stories told by the McClure’s letter writers offer insight into the ways in which photography offered late nineteenth-century Americans resources for making sense not only of Lincoln the man and myth but of themselves as well.