1. Thinking Confusion: On the Compositional Aspect of Affect

In this first chapter I will unfold the meanings of a phrase that I have found useful, the compositional aspect of affect in perception. This phrase combines a practical, everyday insight—that feelings matter for how we perceive things, people, ideas, other feelings—with the more technical insights of two theories of emotion: Silvan Tomkins’s affect theory and the object-relations theory of Melanie Klein and those who follow her. Writing on different sides of the Atlantic from within very different institutional, disciplinary, national, and continental contexts, Tomkins and Klein were nonetheless both influenced by and crucially departed from Freud’s writing, in particular his emphasis on the drives in explaining psychic dynamics and motivation. Where Freud (or rather a certain Freud) offered mainly economic understandings of the transformation of instinct or drive into affect (as Laplanche and Pontalis put it, “The affect is defined as the subjective transposition of the quantity of instinctual energy”),1 Klein and Tomkins emphasized the phenomenological qualities of affective or emotional experience and the place of phantasy and everyday theory in moment-to-moment living and thinking. As widely different as they may be, both object-relations and Tomkins’s theory share this focus on affect qua affect (or emotion qua emotion) for understanding motivation and experience.

The term compositional in the phrase above, however, does not come from either of these domains of twentieth-century psychology but from Gertrude Stein’s 1926 lecture “Composition as Explanation.” In this lecture, written at the invitation of the Cambridge Literary Club and delivered at Cambridge and Oxford, Stein offered a meditation on the idea of composition as it defines the contemporary or what it means to be of one’s time, followed by a chronological survey of twenty years of her writing and poetics. That is, “Composition as Explanation,” Stein’s first lecture as a mature writer, both explored composition as an explanatory idea for thinking about art or making in relation to time and history and was itself a composition that served to introduce and explain her exemplary writing to contemporary audiences.2 This reflexive, at once implicative and explicative use of word and idea was characteristic of Stein and indexes her larger poetic project. As a very rough summary, this project could be said to include a constant effort to communicate meaning that refuses to abstract from the lived, present circumstances and conditions of meaning-making; consequently a remarkable attention to the varied material conditions for writing, whether to the sensory aspects (the sight, sound, and feel) of letters and words, or to the grammatical circumstances of writing, or to other situational aspects of writing and reading; and finally, an ability to fold such multiple awarenesses back into the writing itself. I think of these multiple forms of attention that Stein’s writing required of her, and also invites from a reader, as compositional in that they place together elements that many of us are in the habit of keeping apart, often for what we think of as very good reasons, say, for the sake of clarity or intelligibility, propriety, or the appearance of sanity. But in returning again and again to the dynamic, compositional relations between words, whatever words name and the things that words are, the intricate grammatical structures they are embedded in, and the ideas and meanings that emerge from all of these together, Stein’s writings offer some of the most sustained and precise explorations of the varieties of confusion integral to thinking, and to communicating thinking, that I know of.

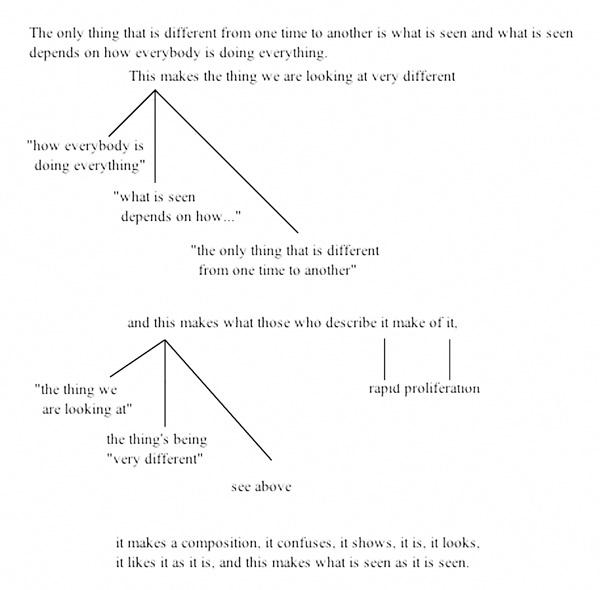

These compositional aspects of Stein’s writing may help us to understand both its so-called difficulty, or the tangle of confusion and frustration that readers may experience, and the excitement and enjoyment that her writing offers to the same readers. As Stein puts it in the lecture, confusion and composition tend to accompany one another in perception: “The only thing that is different from one time to another is what is seen and what is seen depends on how everybody is doing everything. This makes the thing we are looking at very different and this makes what those who describe it make of it, it makes a composition, it confuses, it shows, it is, it looks, it likes it as it is, and this makes what is seen as it is seen” (495). These sentences begin clearly enough: Stein analyzes difference over time as emerging from sensory, spatial experience (“what is seen”), itself dependent on activity—a broadly performative and constructivist understanding, it would seem. This grammatical clarity gets muddied when she foregrounds the specific activities of describing and making, and suddenly compositional agency becomes difficult to locate. Consider a close grammatical reading: “This,” the first word of the second sentence, may refer to the preceding final phrase (“how everybody is doing everything”), or to the dependency relation just elaborated between perception and action, or to the analysis of difference that the entire sentence presents. The subsequent “this” can similarly refer to “the thing we are looking at,” to its difference from itself, or to the same variety of things that the previous “this” referred to. When “it” is introduced and repeated there is an exponential explosion of grammatical parsings, a large (though finite) number that in the ordinary practice of reading creates a kind of overload (fig. 1). While an analytically minded reader may feel initially baffled, with the phrase “it makes a composition” this reader may begin to grasp the qualitative gist of these sentences: how, for Stein, composition is at once agent and patient, naming precisely the possibilities of dynamic self-differentiation conveyed in the grammatical activity of the sentence itself. With the insistent list and the mobile pronoun “it”—“it confuses, it shows, it is, it looks, it likes it as it is”—we may begin to get, in the rhythm of the sentence now, how the kinds of attention that composition invites lead toward both complexity and simplicity, a division and then recombination into some perceivable whole.

With the phrase the compositional aspect of affect I am aiming to name, follow, and explicate the necessary role that affects and feelings play in such divisions and recombinations or in the constitution of objects of perception. Tomkins and Klein offer vocabulary and conceptual tools for this project, as we will see, but so does Stein, who explores the role of feeling in composition most directly in the lecture “Poetry and Grammar” (1934). This lecture begins with a clear set of questions: “What is poetry and if you know what poetry is what is prose.”3 Stein pursues answers to these questions by describing her affective responses to a variety of parts of speech, for, as she puts it, “One of the things that is a very interesting thing to know is how you are feeling inside you to the words that are coming out to be outside of you” (209). She begins with her cowboy modernist preference for verbs and adverbs over nouns and adjectives: “Nouns are the name of anything and just naming names is alright when you want to call a roll but is it any good for anything else” (210). Nominal forms convert what Stein would understand to be essentially dynamic processes or forces into manageable, static, and habit-driven entities; she prefers verbal forms because “they are, so to speak on the move” (212). While this emphasis on movement and process is a general characteristic of modernist thinking, less familiar is Stein’s particular association of movement with the productive possibilities of mistake, and her further association of mistake with enjoyment. “It is wonderful the number of mistakes a verb can make” (211), asserts Stein, whose greatest enjoyment comes from those elements of language that can be most mistaken: “Prepositions can live one long life being really being nothing but absolutely nothing but mistaken and that makes them irritating if you feel that way about mistakes but certainly something that you can be continuously using and everlastingly enjoying” (212). What begins as an investigation into the nature of poetry and prose has become, at this point in the lecture, an articulation of Stein’s poetics of mistake, a poetics for which use and enjoyment are crucial qualities.

Figure 1. Gertrude Stein’s “Composition as Explanation” (1926)

Use, enjoyment, and also life or liveliness: “Verbs and adverbs and articles and conjunctions and prepositions are lively because they all do something and as long as anything does something it keeps alive” (214). Stein’s enjoyment of those parts of speech that are active or promote activity is matched by her disdain for those that undermine activity or life itself. Consider her powerfully negative response to commas, which she describes as “servile”: “they have no life of their own, and their use is not a use, it is a way of replacing one’s own interest” (219). A comma, “by helping you along holding your coat for you and putting on your shoes keeps you from living your life as actively as you should lead it” (220). I hear in Stein’s disdain rejections of dependence that are both masculinist and feminist: she casts the comma as at once chivalrous suitor and protective mother and rejects them both. But as she continues to explain her feeling for commas and the particular experiences that they interfere with, we may hear something else as well: “I have always liked dependent adverbial clauses because of their variety of dependence and independence. You can see how loving the intensity of complication of these things that commas would be degrading. Why if you want the pleasure of concentrating on the final simplicity of excessive complication would you want any artificial aid to bring about that simplicity” (220). Commas help a reader in parsing a sentence to reach the “final simplicity” or meaningful gist of a complicated sentence; Stein rejects this assistance, preferring to experience the varieties of dependence and independence, the mistakes and confusions that grammatical form makes possible.

While Stein appears to be naturalizing grammar by contrast with the “artificial” technology of the comma, the following passage makes clear that, for her, a sentence is also a tool, no less artificial or prosthetic. Her primary point is to enter into a lively circuit with this unusual tool:

When it gets really difficult you want to disentangle rather than to cut the knot, at least so anybody feels who is working with any thread, so anybody feels who is working with any tool so anybody feels who is writing any sentence or reading it after it has been written. And what does a comma do, a comma does nothing but make easy a thing that if you like it enough is easy enough without the comma. A long complicated sentence should force itself upon you, make you know yourself knowing it and the comma, well at the most a comma is a poor period that lets you stop and take a breath but if you want to take a breath you ought to know yourself that you want to take a breath. (221)

Stein’s point is not to distinguish the natural from the artificial (her approach, here as elsewhere, is post-Romantic) but to distinguish between different kinds of tools and experiences, those that promote life and its tangles and those that do not. If commas cut up or impose breaks on the rhythms of respiration, a long complicated sentence exerts a different kind of force. Both breathing and grammatical parsing are characterized by a movement back and forth between unconscious, automatic behavior and conscious, deliberate attention, and both nudge your attention toward reflexive awareness: as Stein puts it, just as a sentence should “make you know yourself knowing it,” so “you ought to know yourself that you want to take a breath.” Stein enjoys grammatical mistake, then, because it indexes a complexity she associates with life and requires her to pay attention to what is ordinarily automatic or unconscious, the subtle circuits of grammar and respiration. She aims to write sentences that induce a reflexive awareness of these circuits, that promote a lively determination of structure and meaning through readerly deliberation.

I use the word deliberation in order to echo Steven Meyer’s description of Stein’s approach to what he calls “deliberate error,” “error that may nonetheless be correct, error, that is, with the means for correction built into it. If such error requires deliberation, it also rewards it.”4 Meyer discusses this aspect of Stein’s poetics as part of his careful analysis of the relations between her early neuroanatomical training and later writing practices. As a student in the 1890s Stein had worked in the field of experimental physiological psychology, first as an undergraduate at Radcliffe and Harvard with William James and Hugo Münsterberg, and then at the Anatomical Laboratory at Johns Hopkins, where she pursued a medical degree. At Hopkins she made models of human brain tracts and encountered difficulties that led her ultimately to reject a career in medicine and take up writing as a medium for experiment. Meyer understands Stein’s career change as in part a consequence of her resistance to anatomical perspective and to the exclusion, in her medical training, of what he calls a “neuraesthetic” perspective, which he defines as “a sensitivity to the physiological operations of one’s own nervous system” (58). If an anatomical perspective on the brain gives an observer a clear visual sense of brain structure, it fails “to convey any sense of the actual conditions in which these structures exist—any sense, that is, of their physiological conditions” (96). In this way Stein was very much a student of William James, who emphasized the value for knowledge practices of paying attention to one’s bodily, physiological experiences. But, as Meyer points out, Stein’s insistence on writing and reading as the primary locus for a reflexive circuit of knowledge and feeling distinguishes her from James; for Stein, there appears to be some ultimate continuity between writing and physiology that permits writing to become not only a symbolic vehicle for communicating ideas but itself matter for experiment and experience.5

Stein’s thinking on the liveliness of words and her attention to the role of feeling in composition engages critically with her nineteenth-century training in the life sciences. At the same time, her compositional poetics of deliberate error, with their implied notion of negative feedback as a means for correction, offered her access to aspects of what was not yet, in the first half of the twentieth century, called organized complexity (although ideas of circular causal relations and nested relations of dependence and interdependence between systems were percolating at the intersections of a number of disciplines). In this context consider how Stein’s keen excitement for the combinations of grammar foregrounds the notions of emergence and self-organization, two important ideas from later biological systems theory: “when I was at school the really completely exciting thing was diagramming sentences and that has been to me ever since the one thing that has been completely exciting and completely completing. I like the feeling the everlasting feeling of sentences as they diagram themselves./In that way one is completely possessing something and incidentally one’s self.”6 Here again Stein’s activity and that of the sentence enter into feedback or circuit relations, permitting an eccentric self to emerge from the way that words can, under observation, self-organize into complex whole sentences. Both the words complex (in the sense of composite or compound) and complete (to make whole or entire, having all its parts or elements) inhabit the same semantic field as the word composition, so central to Stein’s poetics.

I make these points about complexity and composition in order to bring Tomkins into my discussion, the American psychologist whose theory of what he called, from the mid-1950s on, “the affect system” was crucially informed by those midcentury sciences of organized complexity, cybernetics and systems theory. Stein and Tomkins are not as distant, either historically or conceptually, as I had initially assumed, connected as they are through William James and the laboratory tradition of physiological psychology. Strangely, their career trajectories, although a generation or two apart, are almost symmetrically reversed. In 1930, about thirty years after Stein dropped out of medical school, Tomkins completed his bachelor’s degree at the University of Pennsylvania with a concentration in playwriting. He pursued graduate work in psychology and philosophy (also at Penn), taking two graduate seminars in the early 1930s with another student of James’s, the philosopher Edgar A. Singer Jr., who was born a year earlier than Stein.7 Tomkins finished his doctorate in 1934 and moved on to do postdoctoral work in philosophy at Harvard (with the logician Quine, among others) before joining Henry Murray’s group studying human personality at the Harvard Psychological Clinic (which had been founded by James’s colleague Morton Prince). Whereas Stein left Harvard and the life sciences for writing, Tomkins moved from playwriting (and Pennsylvania, where Stein was born) to Harvard and the study of personality. These two very different writers and thinkers shared an explicit filiation with James, academic training in the psychologies of their moments, and a dissatisfaction with the forms of empiricism that guided this training. Tomkins, as much as Stein, became explicitly concerned with the role that affect plays in perception and cognition.

I introduced the basic elements of Tomkins’s theory of affect in my introduction; here I would like briefly to explore those aspects of his work that offer theoretical traction on the idea of the compositional aspect of affect. Tomkins proposes specific roles for affective experience in the perception of objects, as, for example, in his theory of the role of positive affect in the development of infant perception. He suggests that the affect of interest-excitement sustains infant attention, acting as a motive for “perceptual sampling” (AIC 1: 347) or the many and various acts of perspective-taking that permit the infant to become acquainted with a new object: “In learning to perceive any new object the infant must attack the problem over time. Almost any object is too big a bite to be swallowed whole. If it is swallowed whole it will remain whole until its parts are decomposed, magnified, examined in great detail, and reconstructed into a new more differentiated object” (1: 347–48). Tomkins lists many kinds of perspective-taking, including looking at an object from different angles, watching its movement, switching between perceptual and conceptual orientations, remembering and comparing the object in time, touching, stretching, pushing, or squeezing it, putting it into one’s mouth, making noises with it, and so on, and suggests that “without such an underlying continuity of motivational support there could indeed be no creation of a single object with complex perspectives and with some unity in variety” (1: 348). Enjoyment plays an equally important role in infant perceptual development: by providing “some containment” for the infant’s distractibility, it lets the perception of an object remain in awareness longer (1: 487). The enjoyment of recognition then motivates the return to what is emerging, in perception, as a bounded object.

As in infancy, so in adult life: for Tomkins, both positive and negative affects continue to play essential roles in perception because of that most significant of the freedoms of the affect system, the freedom of object. Accompanying this basic freedom is what Tomkins calls “affect-object reciprocity,” the ways that affects and objects come to be reciprocally interdependent. He puts it this way: “If an imputed characteristic of an object is capable of evoking a particular affect, the evocation of that affect is also capable of producing a subjective restructuring of the object so that it possesses the imputed characteristic which is capable of evoking that affect. Thus, if I think that someone acts like a cad I may become angry at him, but if I am irritable today then I may think him a cad though I usually think better of him” (1: 133–34). In this example anger may lead Tomkins to information about himself (his prior mood) or about others (their callousness), or both; just because Tomkins is irritable when he makes his observation does not mean that his friend is not a cad (“In a moment of anger, characteristics of the love object which have been suppressed can come clearly into view” [1: 134]). These dynamics, most often described in terms of (what psychoanalysis calls) the defenses of projection and introjection, are not easily avoided, nor should they be, according to Tomkins, since affect-object reciprocity plays a crucial role in experiences of coming to knowledge: “There is a real question whether anyone may fully grasp the nature of any object when that object has not been perceived, wished for, missed, and thought about in love and in hate, in excitement and in apathy, in distress and in joy. This is as true of our relationship with nature, as with the artifacts created by man, as with other human beings and with the collectivities which he both inherits and transforms” (1: 134–35).

Both Stein’s compositional poetics and Tomkins’s theory of the role of affects in perception offer access to a reflexive and dynamic middle ground, what Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick has termed “the middle ranges of agency.”8 I believe that these middle ranges are important to think about; the alternative, a continual oscillation between phantasies of omnipotence and abjection, is exhausting and unhelpful. But these middle ranges are difficult to conceptualize and inherently confusing because affective dynamics do not obey the logic of noncontradiction: “The logic of the heart,” as Tomkins puts it, “would appear not to be strictly Boolean in form, but this is not to say that it has no structure” (AIC 1: 134). Where Tomkins addresses this difficulty by seeking a theory that can capture the complexity of affective experience, Stein explores confusion itself, seeking to make it palpable, available, and tolerable. For Stein, acquainting oneself with confusion is an important part of what it means to know and to experience understanding; as she puts it in her lecture “Portraits and Repetition,” “There is another thing that one has to think about, that is about thinking clearly and about confusion. That is something about which I have almost as much to say as I have about anything.”9

It turns out that the word confusion and its cognates do appear regularly in Stein’s lectures. In “Paintings,” for example, she writes toward the end, “I wonder if I have at all given you an idea of what an oil painting is. I hope I have even if it does seem confused. But the confusion is essential in the idea of an oil painting.”10 Etymologically confusion means “to pour together, to blend or melt in combination or union,” a literal description of what happens with viscous oils when mixed and used for painting. But Stein insists on the necessary relation between confusion and “the idea of an oil painting” (emphasis added); at stake here is precisely the movement from the literal to the figurative or symbolic, from a perceptual experience of paint on canvas to a conceptual experience of picture or representation and back again. This confusing movement back and forth between medium and form has been the subject of Stein’s lecture all along, and at this point she is wondering whether she has successfully communicated her poetics, for which such movement is crucial. These modernist poetics would become extremely influential in mid-twentieth-century visual art criticism, and it is usual to associate Stein’s writing with a move toward abstraction in the arts, best captured, for example, in Clement Greenberg’s arguments against figuration.11 But Greenberg’s program for postwar American abstraction is not Stein’s, for whom abstraction poses the greater threat to experiences of understanding and communicating understanding than does confusion. For Stein (and, as we will see in chapter 4, the psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion as well), accommodating confusion and the frustration that accompanies it make thinking possible.

“The difference between thinking clearly and confusion,” asserts Stein in “Portraits and Repetition,” “is the same difference as there is between repetition and insistence.”12 What is this difference? Stein claims to have discovered the latter distinction, crucial for her poetics, at the age of sixteen or seventeen, when she spent a summer in Baltimore living with “a whole group of very lively little aunts who had to know anything” (168). Listening to her aunts talk and listen to each other taught Stein about the importance of emphasis: “expressing any thing there can be no repetition because the essence of that expression is insistence, and if you insist you must each time use emphasis and if you use emphasis it is not possible while anybody is alive that they should use exactly the same emphasis” (167). What appeared to be repetition of words and sentences in her aunts’ conversation often involved variations in mood, modality, tense, or tension. When repetition did occur, it was due to a lapse of attention, to tiredness or boredom, to the failure of listening: Stein concludes that “Nothing makes any difference as long as some one is listening while they are talking” (170). She associates thinking clearly with a sustained attention to these differences in emphasis; in fact, for Stein, creativity or compositional difference itself emerges from a sustained attention to the affective circuits between listener and speaker, even or especially when these are the same person. Confusion, by contrast, takes place when this circuit of attention is interrupted, when insistence and difference subside into senseless repetition of the same, and when remembering takes the place of attention to the present.

Listening and talking at the same time, it turns out, is one of Stein’s working definitions of genius: “it is necessary if you are to be really and truly alive it is necessary to be at once talking and listening, doing both things, not as if there were one thing, not as if they were two things, but doing them, well if you like, like the motor going inside and the car moving, they are part of the same thing” (170). Once again she offers a technological figure to describe what is most alive: here she figures the coordination of talking and listening by a coordination of a motor “going” and a car “moving,” by the relation between motivation and behavior. Stein’s interest in people’s motors or what she calls “the rhythm of anybody’s personality” (174), her whole portraiture project is a way to explore motivation at once continuous with and a radical break from her early training in physiological psychology. Her attention to “the motor going inside” can be heard in two ways at once, especially when she returns to this figure late in the lecture: “As I say a motor goes inside and the car goes on, but my business my ultimate business as an artist was not with where the car goes as it goes but with the movement inside that is the essence of its going” (194–95). Stein brings her awareness not to behavior (where the car goes) but to “the movement inside,” that is, both to what is going on inside a person and what goes to the inside of a person, motivation within and without. Stein’s language addresses the status of affects or motives as at once inside and on their way inside from elsewhere, and her method of doing portraits requires that she attend precisely to these movements of affect, especially between her portrait subjects and her self: “I must find out what is moving inside them that makes them them, and I must find out how I by the thing moving excitedly inside in me can make a portrait of them” (183). I will discuss Stein’s affective, transferential portraiture method in chapter 4. For now I would simply point out that these movements are essentially confusing (in terms of location and belonging) at the same time that they make up the very liveliness she wants to capture in her portraits: “But I am inclined to believe that there is really no difference between clarity and confusion, just think of any life that is alive, is there really any difference between clarity and confusion” (174).

Certainly the lively mobility of affect, how affect moves between outside and inside, between selves or between self and object (what Tomkins describes in terms of affect-object reciprocity), makes affect a primary source of confusion. But this general characteristic is not the only source: “As I say a thing that is very clear may easily not be clear at all, a thing that may be confused may be very clear. But everybody knows that. Yes anybody knows that. It is like the necessity of knowing one’s father and one’s mother one’s grandmothers and one’s grandfathers, but is it necessary and if it is can it be no less easily forgotten” (173). Stein moves from a universal “everybody” to an individual “anybody,” both as subjects of knowledge, then suddenly introduces a familial middle ground as an object of knowledge. Just as her gossiping aunts led her to the distinction between repetition and insistence, now she locates family as a primary source of confusion: the mixing up of environments, of genes, of persons that create family resemblances, strange throwbacks, and unpredictable mutations. The terrain of clear confusion summons up, one imagines rather surprisingly for Stein, the feelings of dependence and independence that accompany family life, the necessity both to know and to forget the difficult vicissitudes of infancy, childhood, and beyond.

The difficulties of infancy occupied Melanie Klein greatly; indeed for Klein, the intensity and volatility of especially negative emotional experience explains, in part, why the first year or two of life is generally unavailable to adult consciousness: it’s too painful (and pleasurable) to remember. For Klein, these intensities continue to inform later mental experience and behavior, or, as Robert Hinshelwood puts it, “If Freud had discovered the child in the adult, then Klein believed she had discovered the infant in the child.”13 Born in 1882 (eight years after Stein), Klein was part of the early wave of central European psychoanalysis, undergoing analyses with Sandor Ferenczi and Karl Abraham before settling in London in the mid-1920s. The British-based school of object relations that she helped to initiate differed from what came to be called classical psychoanalysis, especially in emphasizing qualitative relations with the important early “objects” or people in the life of a patient. Where Freud’s main clinical methods involved verbal techniques (free association and dream interpretation), Klein developed techniques of play and play interpretation in her work with children, for which the material of gesture, vocal intonation, spatial manipulation of toys, and other nonverbal communication became relevant for observation. Bringing her interpretive techniques to adult analysis, Klein developed the important understanding that infantile unconscious phantasies accompany all behavior and that these phantasies are enacted both verbally and nonverbally in the here and now of experience.

Such an emphasis on the here and now, or what Stein would call the “continuous present,” is one common ground between Klein and Stein, between whom there was little overt historical connection. Unlike Tomkins and Stein, who can be intellectually and disciplinarily linked, Stein would appear not to share with Klein any such personal or professional filiations. In fact Stein staunchly and publicly rejected psychoanalysis, most famously in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, where she claimed never to have had any “subconscious reactions.”14 By contrast with her brother, Leo, Gertrude shied away from Freud and the popular uptakes of psychoanalysis in the first decades of the twentieth century.15 As a queer woman writer Stein had excellent reasons to reject heteronormative psychoanalytic and other psychological discourse and the threats it might pose to her. But Stein and Klein were participating in similar modernist projects in their efforts to become acquainted with and give verbal form to elements of experience that are difficult to access and entertain in consciousness. These efforts share a few basic methods or principles: in addition to an insistence on the present of awareness, they shared a form of attention to what in psychoanalysis is called the “total situation,” a suspicion of abstraction as a way of coming to knowledge and a sense of the inevitable role for confusion in thinking.

To approach these shared concerns or methods, consider this long citation from an excellent essay by Lyn Hejinian on the role of compassion in Stein’s early book Three Lives:

Like Flaubert, Stein was interested in compassion as an artist, which is to say formally; this is at the root of Stein’s desire (and ability) to “include everything.” It is a clinical, not an encyclopedic, impulse; there is nothing that can be considered unworthy of attention, no subject that is too trivial, too grimy, too mundane, too abject, too foible-ridden, too ordinary. Inclusiveness in this context means a willingness to look at anything that life might entail; as such, it was a central tenet of the “realism” which claimed Flaubert for its “father.” And the detachment which it requires is what permits the shift from manipulative to structural uses of compassion, a term whose connotations modernist realism transformed. What had previously served (antirealist) sentimentality now informed (merciless) compositionality.16

Detached and compassionate attention that includes everything: this closely resembles the total analytic situation in which nothing is too minor to be overlooked and everything may have value. For Klein, the importance of the total situation lies not in a fantasy of totalized description or knowledge but in the variety of ways that the patient expresses unconscious phantasy, including deeply negative wishes or thoughts aimed toward the analyst. Klein tried to give what she called “deep interpretations” or verbalizations of unconscious phantasies and discovered that these often had the surprising and therapeutic effect of freeing the patient to engage in more varied creative activity. Interpreting especially negative phantasy tended to open up a generous space in which the most destructive impulses can be voiced and entertained rather than inhibited or repressed for fear that they might trigger immediate, dangerous reprisal (by an other or by a different part of the self). In this context the analyst’s merciless attention becomes a version of what Hejinian calls the structural use of compassion, characteristic of Stein’s (and other modernists’) compositional practices.

What might be structural about this use of compassion? Stein’s emphasis on compositional differences, that is, on differential relations as themselves constituting objects or identities, shares a basic insight with Ferdinand de Saussure’s linguistic theory, including an emphasis on nonmimetic understandings of language. Stein puts it this way in “Poetry and Grammar”: “Language as a real thing is not imitation either of sounds or colors or emotions it is an intellectual recreation.”17 But where Saussure’s structuralism and its uptakes in later anthropology and literary criticism focused on groups of static binary oppositions as productive of value and meaning, Stein’s structuralism is much more Kleinian, involving acts of what Susan Howe calls “linguistic decreation” as well as intellectual re-creation.18 The poetic project of Tender Buttons (written in 1912–13, around the same time Saussure gave his course in general linguistics) offers the most striking examples of Stein’s Kleinian structuralism, beginning with its title, which invites a reader to think of everyday household objects as well as exceptionally sensitive body parts (nipples, clitorises, fingertips). In three sections this writing traces a broad itinerary from “objects” to “food” to “rooms,” that is, from poems that attempt to decreate/re-create things that one can see outside of one’s body, to decreations/re-creations of those kinds of things that can be taken into the body as food and digested, to interior spaces that are formed from such processes of incorporation. The first poem in this collection, titled “A carafe, that is a blind glass,” offers a sense of the structuralist aspect of Stein’s project:

A kind in glass and a cousin, a spectacle and nothing strange a single hurt color and an arrangement in a system to pointing. All this and not ordinary, not unordered in not resembling. The difference is spreading.19

A carafe is, among other things, a container used for pouring, while a “blind glass” is, again among other things, a nonreflecting mirror: the linguistic “system to pointing” that Tender Buttons begins with offers a moving viscosity and opacity rather than a still clarity and mirroring of meaning. The poem’s “kind” and “cousin” evoke the familial as a model for differences, an “arrangement” that is neither “ordinary” (ordinal, numbered) nor “unordered”: the representational system here is structured but not static. Its mobility is in part a consequence of its destructive energies, the sense of shattered crystal and spilled “spreading” of bruised difference or “hurt color” in a continuing present of the writing.

Many of the poems in the first section communicate the sense of taking a perceived object to pieces and putting it together in a new way so as to see it, and say it, as if for the first time. In “Poetry and Grammar” Stein describes the poetic project of Tender Buttons this way: “I began to discover the names of things, that is not discover the names but discover the things the things to see the things to look at and in so doing I had of course to name them not to give them new names but to see that I could find out how to know that they were there by their names or by replacing their names.”20 As an infant discovers “the things to see” through bodily manipulations of the thing it is perceiving, including a discovery of a thing’s solidity, persistence, and usability through efforts at destroying it, so Stein enacts this process of perception in language, a process that involves discovering how names and things are intimately, intricately related: “After all one had known its name anything’s name for so long, and so the name was not new but the thing being alive was always new.”21 The modernist goal of generating new poetic form to accord with the newness of things in nonhabituated perception brings her attention to the dynamics of writing itself as a space of recreation or childlike play. Consider another poem, “Objects,” from the first section it shares a title with:

Within, within the cut and slender joint alone, with sudden equals and no more than three, two in the centre make two one side.

If the elbow is long and it is filled so then the best example is all together.

The kind of show is made by squeezing.22

Stein begins this poem by counting feet: one iamb (“Within”), two iambs (“within the cut”), three (“and slender joint alone”), as if generating these feet from the idea of “within” and the word that names this idea. Counting serves to modify the anxiety of “the cut” (between word and thing), a technique that turns into a balancing act or an effort to fill in the gap or even out the sentence (“with sudden equals and no more than three”). The following phrase continues reflexively to count the center feet, but what counts as the center keeps changing as this long, jointed sentence goes on. A new sentence or joint appears next, an “elbow” that may disappear from sight or become filled in when the arm stretches out; the poem now encourages us to look at the sentence or arm “all together” rather than anxiously to count feet or body parts separately. In the final sentence Stein announces something about her compositional method, how it feels to make a poem or “show” of the kind we are reading: slow and gradual, as if squeezing something out of the body (excretion).

This poem reads like a set of instructions or a recipe for how to produce a middle or third space in and of writing, an exemplary recipe for Stein’s project insofar as any of her poems are exemplary. Not that it’s particularly easy to follow Stein’s recipes; rather she offers readers specific examples of de-habituated linguistic and perceptual experience and opportunities to step away from habit ourselves. Of course, objects is also a verb, and in these poems Stein gives us her objections to reifications of nominal forms. In order to read Stein at all it would appear that one needs to give up any sense of dialectical mastery that language use ordinarily comes with and begin, as it were, all over again. For example, here’s a poem called “Oranges in” from the end of the second section “Food.”

Go lack go lack use to her.

Cocoa and clear soup and oranges and oat-meal.

Whist bottom whist close, whist clothes, woodling.

Cocoa and clear soup and oranges and oat-meal.

Pain soup, suppose it is question, suppose it is butter, real is, real is only, only excreate, only excreate a no since.

A no, a no since, a no since when, a no since when since, a no since when since a no since when since, a no since, a no since when since, a no since, a no, a no since a no since, a no since, a no since.23

I hear the word nuisance repeated in what strikes me as a stubborn, irritated or despondent nursery rhyme that takes constipation (“Whist bottom whist close”) or some other excretory difficulties as subject. These difficulties are accompanied by the memory of childhood foods (“Cocoa and clear soup and oranges and oat-meal”) used to treat a painful condition (“Pain soup”), memories that deliver a depressing sense that “real is only, only excreate.” This feeling that the world and one’s writing have gone to shit (“cocoa” to caca) may be one natural and fitting conclusion to a section on food, but one that triggers a tantrum of sobs: the poem appears to struggle against returning (“since when”) to some early, fraught moment. The title “Oranges in” evokes origins: the poem recognizes how origins and the felt imperatives of origin stories (both to tell these stories and to feel determined by them) are a nuisance, distracting from the presence of new perception; the poem also recognizes how such distractions are nearly inevitable, natural, difficult to counter—you can’t say it too often, a real nuisance.

For object-relations theory, the near inevitability of being distracted from the here and now of perception is a consequence of the constant activity of the basic defenses of projection and introjection in unconscious phantasy. Klein differed from Freud in her theory of phantasy. For Freud, fantasy is a form of (sometimes conscious) hallucinatory wish-fulfillment resorted to by the infant when an instinctual desire is not gratified. But for Klein, as Hinshelwood defines it, “unconscious phantasies underlie every mental process, and accompany all mental activity. They are the mental representation of those somatic events in the body which comprise the instincts, and are physical sensations interpreted as relationships with objects that cause those sensations.”24 Unconscious phantasies are ubiquitous and accompany any experience of thinking or perception; rather than substituting for external reality, in object-relations theory “the investigation has been into the way in which internal unconscious phantasy penetrates and gives meaning to ‘actual events’ in the external world; and at the same time, the way the external world brings meaning in the form of unconscious phantasies.”25 If the term compositional involves the bringing together of elements that we are often in the habit of keeping apart, this notion of unconscious phantasy offers the most sophisticated and thoroughgoing interpretation of the mixed-up nature of composition that I am aware of. Like Tomkins’s understanding of affect-object reciprocity, Klein’s notion of phantasy complicates any simple subject-object and interior-exterior oppositions, requiring reciprocal understandings of the role of mental experience in the constitution of objects in perception and the role that external objects play in the constitution of subjective experience.

The epistemological stakes of Klein’s notion of phantasy emerged during the 1930s as her differences from Freud grew. These differences were sharpened and exacerbated when a number of Viennese psychoanalysts, including Freud and his daughter, Anna (who also specialized in child analysis), moved to London in 1938 to escape the war, eventually prompting the so-called Controversial Discussions of the first half of the 1940s, in which Klein and her supporters tried to consolidate their theories and defend themselves against rejection by the British Psychoanalytic Society. Klein asked Susan Isaacs to write and deliver the first paper, “The Nature and Function of Phantasy,” a lucid and provocative treatment of the idea.26 As Meira Likierman puts it in her description of this paper, “Isaacs’ account intimates that phantasy creates the earliest system of meaning in the psyche. It is the element that gives blind human urges a direction, and so is an instinctual mode of thinking based on the response to worldly impingements.”27 If for Freud instincts “were the fundamental motivational forces in mental life . . . neither purely physiological nor purely mental,” then, as Isaacs put it in her essay, “Phantasy is the mental corollary, the psychic representative of instinct. And there is no impulse, no instinctual urge, which is not experienced as (unconscious) phantasy.”28 Phantasy gives psychic shape, texture, volume, or sense to the instinctual urges and forces that we constantly undergo; it is, as Hinshelwood puts it, “the nearest psychological phenomenon to the biological nature of the human being.”29

One significant value of Tomkins’s affect theory is its redescription of what Freud called “instinct” or “drive”; for Tomkins, qualitatively different affects (which, like instincts, are at the border between the psychic and the physiological) provide more varied kinds of motivation than the Freudian dualisms (either of libidinal and hunger instincts or, later in his theory, life and death instincts). In the interest of working out a compatibility between Klein’s and Tomkins’s theories, I suggest that affects may be thought of as specific qualities of relation that become worked over in or as phantasy. Where affect gives quality to phantasy, phantasy lets affect take shape and move as part of the process of composing objects. For example, for Tomkins, the infant’s hunger is amplified by its distress: the cry of distress communicates both to the infant and to its mother that something is wrong. In Klein’s theory the hungry infant has a phantasy of something biting its stomach from the inside. Bringing these descriptions together we have the negative affect of distress (along with fear and anger) motivating and qualifying a phantasy that gives these affects specific psychic content; the phantasy itself can then reactivate this particular affective bundle for the infant even when it is not literally hungry. Likierman puts it this way: “the particular scenario out of which a phantasy is composed is always and specifically based on object relations, in which an object is either treated in a particular way, or else itself meting out a particular kind of treatment to the subject. . . . [Isaacs’s and Klein’s understanding of unconscious phantasy] portrays the basis of our mental operations as relational in nature, and suggests that we cannot make sense of our experiences, nor indeed our identity, without referring continually to an internal scenario in which meaning is actualized in an exchange between a subject and an object.”30

This notion of phantasy as “an internal scenario in which meaning is actualized” goes even further than Tomkins does in insisting on the composite nature of thinking and feeling, of perception and conception, and of sensation and imagination. While it is not the case that these binaries are collapsed in Kleinian thinking, nonetheless there is an awareness of the impossibility of ultimately separating these out in experience and a refusal to subordinate experiential awareness to more abstract theoretical descriptions and goals. In this way Kleinian thought shares an attitude with William James’s radical empiricism, and it is no accident that Isaacs cites James early in her essay in answer to the criticism that Klein confuses the perceptual and conceptual “mode of thought.” Isaacs responds by insisting that, while we necessarily use words and concepts in discussing thinking, perceiving, and other mental processes, nonetheless “the mind and mental process, thinking itself, are not in themselves abstract,” that is, we experience thinking as well as perceiving, feeling, and sensing. She goes on: “The concepts we use in talking about perceiving or thinking are alike the result of focusing in attention certain elements in the total content of experience. Even a sensation or a perception is from one point of view partly abstract, since each is attended to by abstracting certain aspects of experience from the total.” For Kleinians, the partly abstract nature of concepts and the words we use to represent them (in this case, the words conception, sensation, and perception) should not replace an awareness of the psychic reality that underlies the experience and gives them meaning. Isaacs writes that “phantasies are, in their simple beginnings, implicit meaning, meaning latent in impulse, affect, and sensation” and goes on a few sentences later: “But words are by no means an essential scaffolding for phantasy. We know from our own dreams, from drawing, painting and sculpture, what a world of implicit meaning can reside in a shape, a colour, a line, a movement, a mass. We know from our own ready and intuitive response to other people’s facial expression, tone of voice, gesture, etc., how much implicit meaning is expressed in these things, with never a word uttered, or in spite of words uttered.”31 For Kleinian thought, there’s always more going on than we are able to say; it shares with James’s radical empiricism a commitment to the possibility of becoming aware of such meaning-giving experience. Unlike James’s, however, Klein’s thinking and techniques share with Stein’s poetic project a commitment to the possibility of communicating this experience in partly symbolic form in the here and now of perception.

The controversial aspects of Klein’s work share something with those of Stein’s: both women were accused of being too confusing, whereas what is confusing and difficult is the object of their investigations and the nature of their projects. During the discussion following Isaacs’s paper Edward Glover, one of Klein’s staunchest opponents (and Klein’s daughter’s analyst), accused Klein and Isaacs of misunderstanding Freud’s theory and inventing a new metapsychology that could accommodate the notion of phantasy. The word confusion appears repeatedly in his angry response as he accuses Isaacs and Klein “of confusing concepts of the psychic apparatus with psychic mechanisms in active operation in the child’s mind, or, again, of confusing both psychic concepts and functioning mechanisms with one of the psychic derivatives of instinctual stress, namely phantasy.” He concludes his angry accusations this way: “I maintain that the compatibility of her ideas with accepted Freudian theory cannot be maintained. It is not possible to have it both ways.”32 This classic paternal expression of the law of the excluded middle accompanied a criticism of what these practitioners considered to be unscientific epistemology: a confusion between the analyst’s descriptions of the mechanisms or psychic processes in actual operation and the analyst’s attempts to understand the patient’s own phantasies of these processes. Hinshelwood points out how “extensive problems of validity, generalizability and communicability in a ‘science of the subjective’” unsettle claims for scientific authority, an uncomfortable situation that often provokes attempts to distinguish a language of metapsychology from a phenomenological language of the patient’s phantasies.33 Here we encounter what Wittgenstein calls the impossible dream of a metalanguage, a separation that can never ultimately secure the desired distance because, as Hinshelwood goes on to point out, psychic experiences are themselves productive of the objects of perception under discussion, or, to put it another way, phantasy underlies and itself becomes theory.

I do not mean to imply that confusion itself is to be valued positively, but I am interested in when it is dismissed in anger and when it is possible to have some other affective and cognitive relations to it. Klein herself theorized confusion in a discussion of envy in the late paper “Envy and Gratitude” (1957). Taking up Freud’s controversial notion of the death instinct, she defined envy as an innate or constitutional destructiveness directed against what is good or the sources of life itself, in the first instance the feeding breast. Freud had claimed that these powerfully destructive tendencies were “clinically silent,” but Klein observed or inferred them from her analytic experiences, for example, when she describes “a patient’s need to devalue the analytic work which he has experienced as helpful [as] the expression of envy.”34 She goes on to suggest that some patients use confusion as a defense against their own tendency to criticize or devalue: “This confusion is not only a defence but also expresses the uncertainty as to whether the analyst is still a good figure, or whether he and the help he is giving have become bad because of the patient’s hostile criticism” (184). This uncertainty over good and bad in the “negative therapeutic reaction” is both an expression of envy as well as a defense against it, and throughout her essay Klein consistently presents confusion in this double role.

To elaborate further: according to Klein, the infant lives the first few months of its life in what she called the paranoid-schizoid position, which is characterized by the perception of part-objects that are either entirely good (prototypically the breast that comforts and feeds the infant) or entirely bad (the absent breast, the one that withholds or denies milk). Such “normal splitting” permits the infant to begin to internalize the good object at the core of the ego, and eventually this leads, around the middle of the first year, to the integration of what is good and bad into a mixed, contaminated, more realistic whole object, the achievement of what Klein called the depressive position. Confusion enters the developmental picture if “excessive envy, an expression of destructive impulses, interferes with the primal split between the good and bad breast, and the building up of a good object cannot sufficiently be achieved” (192). “I believe this to be the basis of any confusion—whether in severe confusional states or in milder forms such as indecision—namely a difficulty in coming to conclusions and a disturbed capacity for clear thinking. But confusion is also used defensively: this can be seen on all levels of development. By becoming confused as to whether a substitute for the original figure is good or bad, persecution as well as the guilt about spoiling and attacking the primary object by envy is to some extent counteracted” (216). While the confusion that expresses envy is somewhat different from the confusion that acts as a defense against it, both these confusions are fundamental to life insofar as envy is constitutional or innate. If life is accompanied by the instinct toward death or a return to the inorganic state, then some varieties of confusion of the kinds that Klein describes are inevitable.

The concept of envy introduced yet another division among Klein’s colleagues, this time within the group of object-relations analysts, many of whom rejected what they perceived to be a deeply pessimistic idea about innate human self-destructiveness; indeed Freud’s own thinking on the death instinct has been stringently modified by later psychoanalytic theorists. As Laplanche and Pontalis put it, “The difficulty encountered by Freud’s heirs in integrating the notion of the death instinct leads to the question of what exactly Freud meant by the term ‘Trieb’ in his final theory.”35 My interest in these pages has been, in part, to bring together Klein’s and Tomkins’s approaches by foregrounding their approaches to affect. I suggest that Tomkins’s differentiated vocabulary of affect offers more descriptive traction than does the psychoanalytic vocabulary of instinct or drive, and I propose recasting at least some of the phenomena that Klein associates with envy and the death instinct in terms of a variety of innate, negative affects that threaten any sense the very young infant (and at times the older adult) may have of a more coherent or integrated self. In their more intense forms the negative affects offer experiences of extreme bodily destabilization: the rending cries of grief, the burning explosions of rage, the shrinking or vanishing compressions of terror, the transgression of the boundary between inside and outside the body in retching or disgust, all these wreak havoc with any more integrated bodily sense the infant is also in the process of developing.36

For Klein, envy and the defenses against it give rise developmentally to the need to modify envy in the depressive position. Some time in the middle of the first year of life the infant comes to recognize its mother as a whole object who integrates in herself good and bad. This integration is both a subjective experience and an objective change in the infant’s mental structure, a gathering of fragmented ego parts into a more coordinated psychic identity that depends on the infant’s perceptual and affective capacity to recognize the mother’s face. Importantly for Klein, this integration triggers aggression, ambivalence, and a fluctuation between depressive states and the defenses against them, until a more stable understanding of the flawed object permits a more secure relationship or experience of it, along with a commitment to reparative processes. In this context consider how Stein offers up a Kleinian understanding of Cubist method in her short book Picasso (1938). She describes that artist’s vision in terms of the way a small child sees the face of its mother: “the child sees it from very near, it is a large face for the eyes of a small one, it is certain the child for a little while knows one feature and not another, one side and not the other, and in his way Picasso knows faces as a child knows them and the head and the body.” Whereas in ordinary vision “everybody is accustomed to complete the whole entirely from their knowledge”—ordinary vision involves habitual gestalts that permit us to experience whole figures—in Picasso’s vision, “when he saw an eye, the other one did not exist for him and only the one he saw did exist for him and as a painter, and particularly as a Spanish painter, he was right, one sees what one sees, the rest is a reconstruction from memory.”37 Picasso tries to communicate a vision that does not make use of the generalizations or abstractions of memory but rather insists on the present of experience as much as possible, no matter how fragmented.

To put this another way, Picasso’s compositional techniques—as well as Stein’s, whose descriptions of Picasso are almost always also of herself—try not to assume any integrated forms that preexist the act of composition itself. If this notion of composition has the sense of bringing together parts into a whole, such an integration is necessarily accompanied by confusion because of the great variety of defensive strategies working to mitigate the pain of the depressive position. Recall, Stein puts it this way: “But I am inclined to believe that there is really no difference between clarity and confusion, just think of any life that is alive, is there really any difference between clarity and confusion.”38 Perhaps it ought to be possible to distinguish, at times, between kinds of confusion—those that express envy and those that defend against it—as well as between these confusions and the rather different experience of integration of whole objects in the depressive position. But it does not feel like any of this should be particularly easy. This is due to the vitality of affects and the ways they act as compositional agents in the perception of objects: they necessarily both clarify and confuse, motivating the constitution, maintenance, and dissociation of objects. This, I believe, is the basic premise and promise of the idea of composition. Unlike those of her colleagues who took up the modernist slogan “Make it new,” Stein does not renovate anything but rather attends to the contemporariness of awareness and unawareness. The relevant slogan might be “Make it now,” a now that we cannot know whether it is now or not except through forms of attention to affects and their confusing consequences for composition.