In the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis, economists and consumer experts were sharply divided over the timing and severity of any recession. They largely were united, however, on one issue: the continued spending of the rich.

The wealthy, they wrote, had plenty of money, and would therefore keep buying. Michael Silverstein, the consumer guru and co-author of Trading Up, declared in 2005 that the luxury economy was “quite recession proof.”

He was wrong, of course. The luxury economy rose further and fell harder than any other sector of the economy. One reason was the spikes and crashes of high-beta wealth and incomes, described in Chapter 2. Yet the other cause is a new spending pattern among the wealthy, which more closely resembles binges and crash diets than the moderate luxury spending of the postwar period.

Economists Jonathan Parker and Annette Vissing-Jorgensen used the national Consumer Expenditure Survey to get a closer look at these changes. They found the spending volatility of those in the top-earning 10 percent of households is ten times higher than the spending volatility of those in the bottom 80 percent of households: “The consumption of high-consumption households is more exposed to aggregate booms and busts than that of the typical household.”

One survey showed that from 2007 to 2008, consumers with incomes from $150,000 to $249,000 cut their spending by about 8 percent, while those above $250,000 slashed their spending by nearly 15 percent.

Ajay Kapur, a Wall Street equity analyst who also studies the spending habits of the rich, says that the rich are far more unpredictable as consumers than the rest of the population—not because they’re especially frugal during bad times, but because they’re so euphoric during good times, buying boats, handbags, five-star vacations, and new kitchens.

“Their spending behavior is a lot more volatile than the Average Joe’s,” he wrote in a 2009 research note. “On the way up and down, their behavior is considerably more bouncy than the overall economy.”

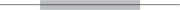

Consider the chart on this page. The dark line represents the ROB ETF, a basket of stocks representing companies that sell to the wealthy—from Porsche and BMW to Sotheby’s, Wilmington Trust, Bulgari, and LVMH. It’s a kind of Richistan Index, representing the consumer economy of the wealthy.

The gray line is a basket of stocks for mainstream U.S. retailers and consumer companies—everything from Walmart and Home Depot to Gap and Macy’s. It’s more like a Main Street Index.

The Main Street Index is fairly stable, like a flat midwestern plain with a lone mountain in the middle. The Richistan Index is more like the Rocky Mountains, with steep drops and mountain peaks. Main Street has a low beta. Richistan’s spending has a high beta.

Kapur explains, “Average Americans spend a lot of their incomes on necessities, things like toothpaste or broccoli or shaving cream. Even if they have to tighten their budgets, they’re still going to buy toothpaste and broccoli. For the wealthy, many of their purchases are discretionary. So if they have a bad bonus, they’re not going to buy a luxury item.”

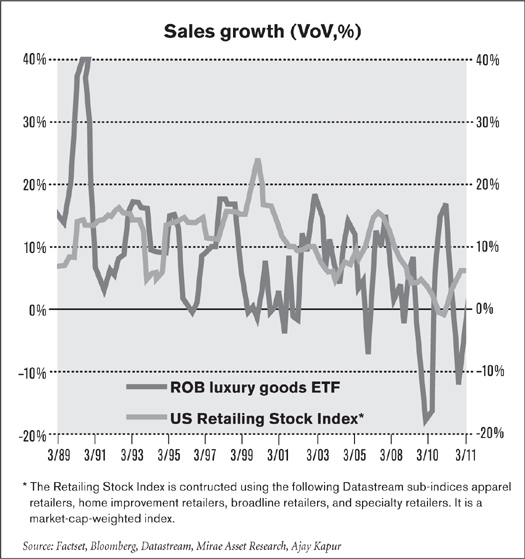

To illustrate this further, the chart on this page shows the prices and sales volumes of the Gulfstream V, one of the most prestigious and pricey private jets. Average prices soared in the late 1990s during the dot-com boom to more than $40 million. Then they crashed by more than 20 percent in the early 2000s.

They rocketed back to $45 million in the late 2000s before falling by about 50 percent in the recession of 2008–2010. Sales volumes are even spikier, falling by more than two-thirds in the early 2000s, and by more than 90 percent in 2008.

Private jets, which many assume to be well insulated from economic ups and downs, have become even more volatile than everyday passenger cars. The same patterns emerge for boats, Bentleys, yachts, Swiss watches, racehorses, and other luxury goods. When times are good for the rich, prices and demand explode. When financial markets crash or asset bubbles pop, the rich virtually stop buying. As Michael Repole, the billionaire founder of VitaminWater and an avid buyer of Thoroughbred horses, told me: “No one needs a racehorse.”

Does anyone really notice if the rich buy a mountain of Manolo Blahniks and Bentleys one year and none the next?

Increasingly they do. In 2005, Kapur was working as an equity strategist at Citigroup and wanted to figure out why rising oil prices weren’t having a greater impact on the consumer economy. He came up with a theory of what he called “the plutonomy,” economies—including that of the United States—that were dominated by spending by the wealthy. Plutonomies behaved differently than did economies dominated by a middle class. While high oil and gas prices may have crimped spending for the middle class, they mattered less to a plutonomy, since wealthy consumers weren’t as affected by higher gas prices.

“There are rich consumers, few in number but disproportionate in the gigantic slice of income and consumption they take,” he wrote. “There are the rest, the ‘non-rich,’ the multitudinous many, but only accounting for surprisingly small bites of the national pie.” This meant that the companies serving the rich would prosper far more than those serving “the rest” during expansions. The old adage “Sell to the masses, live with the classes” had been turned on its head. The new way to prosperity was to “sell to the classes.”

Even Kapur, however, didn’t realize however extreme the plutonomy would become. In his first research notes, Ajay projected that the top 20 percent of Americans by income accounted for up to half of all consumer spending. By 2010, research showed that America’s consumer spending had become even more highly concentrated at the top. Mark Zandi, the chief economist for Moody’s Analytics, found that the top-earning 5 percent of American households accounted for 37 percent of all consumer outlays (outlays include consumer spending, interest payments on installment debt, and transfer payments).

By contrast, the bottom 80 percent of Americans account for 39.5 percent of all consumer outlays. In other words, the few million Americans at the top of the income ladder spend about as much as the hundreds of millions at the bottom.

Zandi also determined that the dominance of the rich was a fairly recent phenomenon. In 1990, the top 5 percent accounted for 25 percent of consumer outlays. Their share held relatively steady until the mid-1990s, when it started inching up past 30 percent. After the bull market of the 2000s, it reached its all-time record. The upstairs-downstairs nature of the recovery in 2010 and 2011, in which the rich rebounded, further boosted the top 5 percent’s share of spending.

As Michael Feroli, chief U.S. economist at JPMorgan Chase, wrote: “The heavy lifting is being done by the upper-income households”—if one defines a Birkin bag as heavy, of course.

We know, then, that the wealthy have become the dominant spenders in the U.S. consumer economy, which itself accounts for two-thirds of the GDP. And we also know that the spending of the wealthy has become more manic due to their fast-changing fortunes and frivolous splurges during booms.

The result is a U.S. consumer economy that will increasingly resemble the Richistan Index. And since more and more of the service economy is devoted to the wealthy, jobs will also move in line with the fortunes of the rich. To understand the human costs of high-beta wealth and the changing nature of working for the rich, consider the plight of the modern butler.

Every year, butlers from across America gather for their annual convention. As conventions go, it is a highly practical and well-mannered affair. The butlers attend panels called “Forming Boundaries with Our Employer” and “Legal Rights of Household Staff,” as well as workshops on smart-home technology, fur coat care, and silver polishing. In between sessions, they eagerly serve each other coffee and tea and trade business cards.

On their final night, the butlers break out the champagne to raise a toast to the Outstanding Private Service Manager, also known as Butler of the Year. The award is like the Oscar of butlering. It’s given to the butler who displays the best traits and traditions of butlerhood—loyalty, hard work, discretion, expert judgment, leadership, and that most elusive but important butler quality known as the “service heart.”

Butlers, by nature and profession, shy away from attention, even in their awards. But in 2007 I was invited to the Denver Sheraton to present the Butler of the Year award.

For me, butlers held a peculiar fascination. They were figures from another era in wealth—the fabled Jeeves with his silver tray, upturned nose, and tux—yet they had managed to transform themselves for the new age of riches. Butlers were now the crisis managers for the newly rich McMansion set. Butlers had their own management training, org charts, spreadsheets, and budgets. They even had their own software to run the increasingly complex lives and homes of the rich, solidifying their image as butlers for the digital age—Jeeves 2.0.

Butlers weren’t even called butlers anymore. They now prefer the title of household manager or estate manager. And they demand salaries commensurate with their training and surging demand for their services: $60,000 to $200,000 a year, depending on experience.

When I first wrote about the remaking of the modern butler in Richistan, to me the butler was a symbol of all that had changed about American wealth, including the changing habits and values of the new rich, who now wanted workaholic, tech-savvy managers rather than the silver-tray-holding house mascots of yore.

I even spent a few days at butler boot camp, a butler training school better known as the Starkey International Institute for Household Management. I learned how to iron a shirt, how to pack a suitcase for a private jet in under five minutes, and how to divide a 30,000-square-foot mansion into zones for cleaning and security checks. I tried my hand at the “ballet of service,” where a team of butlers serves a meal in precise synchronization (I was politely dismissed after nearly dropping a salad plate).

“We are not servants anymore,” said Mary Starkey, Starkey International’s owner and founder. “We are now professionals.”

The winner that year was Curtis Laurent, a dapper and soft-spoken butler from New Orleans. Laurent had grown up in a poor family in New Orleans, and in his early twenties he found work as a chauffeur for a rich banking family in town. He earned the family’s trust and attended Starkey to get his household management degree.

Laurent couldn’t read or write when he got to Starkey. Since he had all the other makings of a great butler, they got him a tutor, and he wound up graduating at the top of his class. He returned to his employer in New Orleans and was promoted to estate manager, responsible for running their four homes and household staff of seven.

Soon after, New Orleans was devastated by Hurricane Katrina. Laurent’s employer evacuated before the storm, but Laurent stayed on and guarded their mansion. During the floods, the home filled with three feet of water, and Laurent saved the valuables—furniture, artwork, rugs—by carrying them upstairs. He stayed awake for days looking out for looters or vandals.

Laurent has what butlers call “the service heart”—an undying dedication to making other people happy and giving them what they need. His idea of service even extended to the community of New Orleans. In the months after Katrina, he launched a charity drive to buy school uniforms and school supplies for underprivileged kids. He also coached Little League and contributed time and money to inner-city youth programs.

“I’m trying to do what I can to help New Orleans move on and improve,” he said to the audience after I handed him his shiny red plaque. “Service to me isn’t just about my job. It’s also about serving my community.”

I called Laurent three years after giving him the award to see how he was doing. Butlers had become something of a barometer of the wealth boom, reflecting both the spending and habits of the newly rich. I wondered what the barometer would tell me about the bust.

Laurent answered the phone with his usual hyperpoliteness.

“Yes, Mr. Frank. So very nice to hear from you. What can I do for you, sir?”

We chatted for a few minutes before I asked him about his job situation. “Oh, I’m doing all right,” he said. “Everything’s good, real good.” As we talked, however, it became clear that everything wasn’t real good after all.

Curtis was vague on the details, since butlers are bound by strict confidentiality clauses in their contracts. But he said that if I wanted to know how the butler economy was doing, I should contact his cousin, Anthony Harris. Anthony used to work for Curtis, before Curtis had to fire him.

“Anthony was a great butler,” Laurent said. “He was about to get another promotion.” He paused. “But it’s a different world now for folks like us.”

I take Laurent’s suggestion and go to visit his cousin on a snowy February afternoon in a suburb of Washington, D.C. Anthony Harris was in the kitchen slicing a chicken timbale with truffles and placing the warm white discs onto a bed of arugula. He was wearing a crisply ironed dress shirt, jeans, and loafers. He was fit and cheerful, with a broad white smile and a palpable eagerness to please.

“Here is course number four,” he says, setting down the timbale and greens. “We have a total of six courses today, so forgive me if I have to keep going back to the kitchen.”

Under any circumstances, Harris’s six-course culinary extravaganza would have been impressive. For the first course, he made figs infused with port wine and stuffed with mascarpone. He made ham and cheese muffalettas, followed by his famous “three-fowl” gumbo, using turkey, chicken, and duck. After the timbale came short ribs slow-cooked for three days and graced with braised Brussels sprouts and oven-roasted potatoes—all carefully paired with wines. He capped it all off with brandy and pepper crème brûlée topped with a burnt-orange glaze.

What made the meal most unusual, however, was the circumstances of its chef. Harris had been unemployed for more than four months. He was staying at his brother’s house in Montclair, Maryland, and living off $400 a week in unemployment checks. He barely had enough money for gas and cell phone bills. Yet he had just prepared a meal fit for a king—or at least a hungry journalist. “The one thing my employer used to tell me is, ‘Harris, you’ve never cooked a bad meal.’ ”

Harris is unceasingly optimistic. A girlfriend once broke up with him because he was so happy all the time. His co-workers at a previous job nicknamed him “No Complaints,” because when they asked how he was doing, he would always say, “No Complaints!” with a beaming smile. He still carries something of the stage presence he gained from years of singing in a popular boy band in New Orleans. “With me, the glass is always half full,” he says. “I’m always trying to find a solution.”

Harris’s true talent, however, is food. He was born to cook. His family is Cajun and Creole, and they own a catering company in New Orleans. Harris spent much of his boyhood in the kitchen with his grandmother, who founded the company. She was legendary for her gumbos, muffalettas, and beignets. From her tiny kitchen, she would cook dinners for three hundred to five hundred people, and her giant cooking pots became characters in Harris’s life, with names like “The Kingpin” and “The Fooler.” Harris spent weekends and nights working at the catering company, making deliveries, cleaning up, or helping out in the kitchen with his six brothers and sisters and army of cousins.

He enjoyed his glimpses into the world of wealth. When he was ten, he visited a mansion on St. Charles Street that was unlike anything he’d ever seen before. “We were doing a delivery around Christmas,” he says. “It was this beautiful mansion, really old, with these Louis XIV chairs and antiques and crown moldings and beautiful art. When we walked inside, the whole house was lit up, these white Christmas lights and candles. They had pine garlands everywhere and a big tree. What I remember was the smell. That pine smell was amazing. And with the lights and the house, it was just beautiful to me.”

Food, however, was his first love. He worked in more than a dozen restaurants and hotels in New Orleans, starting at a Pizza Hut and working his way up to the Ritz Carlton as a sous chef, doorman, and concierge.

His dream was to start a restaurant or become a celebrity chef. He sought out the top chefs in New Orleans and offered to chop onions or do dishes for free just so he could be in their kitchens and learn. Eventually he became proficient at cooking everything from French stews to Italian pastas, Asian fusion salads to chocolate bread pudding.

His signature dish is his gumbo. For Harris, gumbo is more than just a dish; it’s a symbol of his identity, his efforts to both build on his family’s history and forge his own path. “No gumbo ever tastes the same,” he said. “It’s different every time, even if it’s made by the same person. With my gumbo, I started with the recipe from my grandmother, and I added my own thing, my own flavors. It took me years and years to get where I am with my gumbo.”

In 2007, Harris was helping the family catering business with a party hosted by one of New Orleans’s wealthiest families. The family’s household manager, who turned out to be Curtis Laurent, was impressed with how well Harris worked the kitchen and dealt with the guests. He offered him Harris a job as the house butler.

He started work in the home of one of New Orleans’s wealthiest and most powerful families. His starting pay was $40,000 a year.

He enjoyed working with Laurent and the other five members of the house staff—including the chef, who was initially testy about having another cook in the house. Harris’s job was to run errands, handle the family’s travel needs, and serve meals. He also acted as the advance team for the family’s four vacation homes, stocking them with food and supplies before their visits. He loaded up their private jet and helicopter before trips and sometimes filled in for the gardeners, housekeepers, and chef.

After five months, he was promoted to house assistant, making $60,000 a year but often working sixty-hour weeks.

Harris couldn’t divulge the name of his employer, a husband and wife. Like Laurent, he praised their generosity and kindness. Yet he also found their rarefied life somewhat puzzling. The couple lived alone in a 12,000-square-foot home with a staff of seven, “which seemed like a lot to me,” he said. The couple’s two grown children, who lived on their own, would often reach out to Harris to get news from home. Harris even cooked meals for the dogs—chicken soup for one, beef tips for the other.

When the financial crisis hit in 2008, Harris figured that the family and his job were safe—the rich always come out fine, he thought. Yet by the end of 2008, he had begun noticing some changes. The husband, who ran the banking business, became more brusque and stressed. He had always worked long hours, but as the financial crisis deepened, he started working on weekends, often rising before dawn. The family sold one of their vacation homes and put another on the market. They also sold the private jet.

When, in the summer of 2009, Laurent was asked to downsize his staff, he fired the chauffeur and the two groundskeepers. When Harris learned that the family was even cutting back on the regular allowances to the two kids, he knew his job was in jeopardy. “When I heard the kids were being affected, I knew there could be trouble,” he said. “They were family. We were just staff.”

In July 2010, Laurent called Harris into his small office and asked him to sit down. He was holding a folder filled with papers.

“I know what you’re going to say,” Harris said before Laurent could speak.

“How do you know?” said a surprised Laurent.

“Just stuff I’ve been hearing,” Harris said.

Laurent handed Harris his exit papers to sign and asked if he would like to stay on as a part-time consultant without benefits. Harris thanked him, but said he’d rather try to find something full-time.

Over the next six months, Harris scoured the help-wanted ads for butlers, private chefs, and yacht cooks. He went to more than a half-dozen interviews but had no job offers. A producer in Hollywood approached him about making a reality TV show about Harris as a “food ambassador” of New Orleans. It never panned out. A placement agency in New York called him to see if he’d work with a “difficult” family on the Upper East Side that had burned through several butlers in the past year. Harris said he’d be thrilled to accept the challenge. He never got a call back.

As the days and months dragged on, Harris sat at his brother’s house in Maryland. He was running out of leads. He wanted to keep working for the wealthy. But increasingly he was starting to consider other kinds of work—especially in government. His brother works in the U.S. Patent Office, and his sister works for the Labor Department in Atlanta.

“I used to think working for a wealthy family would be the most stable kind of work,” he said, as we drove past the sprawling office buildings of Washington, D.C. “You know, they’ve got means. But now I think maybe the real job security is with the government.”

Harris has plenty of company. Just as the butler boom came to symbolize the money madness of the 2000s, the butler bust illustrates the aftermath and coming era of high-beta wealth. Butlers once expected lifetime employment in the embrace of America’s richest families. Now they’re waking up to a lifetime of booms and busts, of rapid promotions followed by sudden firings.

Staffing experts say butler pay and employment fell more than 20 percent in 2009 and 2010 and has been slow to return. In my own sample of butlers and household manager that I’ve met over the years, about a third were out of work or only working part-time.

Steven Laitmon, co-founder of the Calendar Group, a Connecticut-based household staffing company, told me that rich people today are getting rid of their high-priced armies of chefs, maids, chauffeurs, gardeners, security guards, household managers, and estate managers. They still need help. Yet they’re combining the jobs into one or two “super-staffers” who can do it all.

“We’re getting a lot of requests from clients saying, ‘What we want is someone who can do it all, from cooking and cleaning to paying the bills and watching the kids,’ ” said Laitmon. He noted that many clients mention Alice from the 1970s TV sitcom The Brady Bunch, the comical cook, housekeeper, and kid-watcher who also helped smooth over family problems. Says Laitmon: “A lot of our hedge fund clients want their own Alice.”

The new all-in-one house staffer has a less exalted title and lower salary than the household managers of the boom times. The average salary for an Alice is about $60,000 to $80,000.

“What people are really looking for is a return to homespun caring and comfort,” said Calendar’s Nathalie Laitmon. “Alice represents a return to those values for them.”

Lloyd White, a fifty-eight-year-old butler in Indiana, spent years working as the butler and assistant to a Michigan real estate billionaire. He worked hundred-hour weeks, helped run a large household staff, and traveled constantly aboard his employer’s private jet. By 2010, White was unemployed and struggling to find work.

He came up with a new occupation, one more fitting to the age of high-beta wealth: occasional butler. Rather than tying his fate to a precarious plutocrat, White now rents himself out by the hour to the wealthy or merely affluent families who want someone to help them host parties or events. While he used to make $125,000 a year, now he charges $50 a hour, or about $200 for a single party, helping families with birthday parties, bar mitzvahs, and anniversaries, often helping them shop for supplies at Costco. Many of his employers are the formerly rich who used to throw more expensive parties but are now downsizing. He is the occasional help for the occasionally rich.

“It’s pretty affordable. You can go to Costco and get a cheese plate, some Swedish meatballs, maybe some shrimp cocktail, and petit fours for fifty people, all for about $300,” he told me. “Sure, it’s a different kind of work for me. These aren’t the ultra-rich. But they still like to have a nice party once in a while.”

The butler slump may prove temporary, of course. Butler agencies and training schools—which have a reputation for undying optimism—said that by 2011, they were already seeing demand and salaries for butlers perk up. We may well see another boom in household staff in the next decade, with even more vaunted salaries and titles. Household CEO, perhaps?

Yet the days of lifetime employment in warm embrace of a rich family may be ending. Instead, we may be entering a new age of the occasional butler.

When Anthony Harris started butlering, he assumed that the rich were an enduring feature of our economy. He had seen them withstand recessions, political turmoil, and even the catastrophic floods of Katrina. They always landed on their feet. He figured that people like his employer had so much wealth that their lifestyles would never have to change. Since that lifestyle included butlers, Harris figured his job was among the safest in the country.

What Harris didn’t realize until he was fired in 2010 is that the spending of the rich can turn on a dime, even if they still appear to be rich.

Lloyd White is another human casualty of high-beta wealth. Like Anthony Harris, he was a butler who lost his job during the recession. And like Harris, he has yet to find full-time work. While Harris still burns with excitement and eagerness to reenter the world of wealth, White is older and has the more skeptical view of a battle-scarred veteran of the butler wars. “What a lot of young people don’t understand about this profession is that they’ll be flying high and feeling like they’re part of the family,” he said. “But they’re not part of the family. They are entirely expendable and there’s always a day when you find that out. Usually it’s within two or three years of taking the job. Some of today’s wealthy don’t really care about anyone but themselves. And by the way, some of them are not very good with money.”

White has worked through two full cycles of high-beta wealth. In the late 1990s, he was the food-and-beverage chief at a country club. Many of the members had poured money into tech stocks. The club “was full of a lot of the very wealthy older gentlemen in town,” he said. “In 2000 and 2001, they would sit in the club dining room and watch CNBC and just watch their stocks go down and down. I thought they were all going to have heart attacks. They were all losing a lot of their investments.”

White moved on to work for another club, and then the Michigan billionaire. In 2009, after the billionaire’s health deteriorated, he worked for two other families before being “transitioned out” of his last job in 2010.

While trying to make ends meet as an occasional butler and by doing side work for catering companies, he holds out hope of finding another full-time butler job. “It’s been a whole year since I had a family to take care of,” he said, referring, of course, to a rich family that could employ him.

In the meantime, his own family has suffered. His wife is also part of the high economy built around the rich: she makes couture dresses for wealthy fashionistas. With both of their incomes crashing during the recession, the Whites defaulted on their mortgage. By 2011, the bank had foreclosed their home and was threatening to evict them. “We’re kind of squatters in our own home,” he says.

The Whites plan to move to Florida and patch together employment working as a butler, insurance salesperson, and manager of a website. While he’s grateful for the work he had, there are two stories that stick in White’s mind when he thinks about working for the new rich.

The first is from a job he had working for a family that was worth “in the hundreds of millions,” he said. Every summer, White would accompany the family to their lakeside home in Canada and work as their butler for a month.

In the summer of 2010, he was driving with the mother of the family back from the house and they got to talking about money. White told her he was down to his last few thousand dollars after losing his job and most of his retirement money. The woman grew quiet, then offered a confession. “Lloyd,” she said, “you know we are wealthy. But we lost an awful lot of money during the financial crisis. We lost a third of our wealth.” Her eyes filled up with tears. She told White that in 2008, the family had been spending wildly and had run down their savings, so when stocks crashed in 2009, they were forced to sell some of their stocks at low prices to fund their lifestyle.

“She was literally crying the blues,” White said. “I felt pretty bad. But then I’m thinking, ‘Wait a minute. You’re still worth like $200 million. Maybe you lost $100 million. But it’s kind of hard to feel sorry for someone with $200 million.’ I mean, I was down to my last $2,000 or $3,000. It’s all relative. Anyway, I tried to be sympathetic.”

Another family White worked for was also worth millions. During the recession, the family’s income couldn’t keep pace with their exuberant spending habits, which often included new Maseratis and house renovations. During a low point in the recession, one of the adult sons in the family told the house manager that if anyone was going to cut back to make ends meet, it would be the household staff.

“He said to him, ‘I’m not going to be the only one to suffer because of these losses. People who work for me also have to take a hit.’ ” After the speech, the son fired the house chef and demanded pay cuts from all the other staffers who wanted to keep their jobs. The savings from the cuts only amounted to about $150,000 a year. As White puts it, “That’s less than he spent for the new Maserati that he wrecked.”

White said he was initially stunned by the remarks. It was further proof of the sense of entitlement, arrogance, and exploitativeness of the new rich, and their utter contempt for all the dim-witted plebes who weren’t as rich. But White later realized the son was right. It was the little folks—the staffers, the butlers, the army of people who serve and cater to the rich—who seem to bear the brunt of the financial pain when the high-beta rich take a fall. It wasn’t an opinion. It was economic fact.

“You can ride the wave and hopefully save some money and be smart with your investments along the way. You should ride that wave as long as you can. Because eventually, that wave will come crashing down.”

When the waves of high-beta wealth come crashing down, they can affect an entire town like Aspen as well as a much larger canvas like the American consumer economy. In a plutonomy, we’re all occasional butlers now, relying on the increasingly erratic jobs and spending of the wealthy.

As the rich account for a growing share of taxes, the high-beta swings will also be felt in the broader realm of government. In the next chapter, we’ll find out what a butler and Bentley dealer have in common with the governor of California.