INTRODUCTION

Giving Up the Gulfstream

In the spring of 2006, at the glittering peak of America’s Second Gilded Age, I flew to Palm Springs, California, to meet one of the nation’s newest billionaires.

His name was Tim Blixseth. And, like many new billionaires at the time, he had more household staff than he could count. “Somewhere around a hundred” was his best guess at the time (it was actually 110). When I landed, I was greeted by one of his minions, a chipper Filipino chauffeur named Jesse, wearing khakis and a crisp white polo shirt, the universal uniform for helpers of the rich.

“Welcome, Mr. Frank!” Jesse said. “I’ll be taking you to the residence.”

Jesse and I climbed into his shiny black Land Rover, and he handed me a cold Fiji water and a lemon-scented towel from a cooler in the armrest. We pulled out of the airport and drove on Route 111, past the strip malls, car dealerships, and fast-food restaurants, and out toward the open desert. The sun was setting behind the orange peaks of the Santa Rosa Mountains, and a cool night breeze drifted across the valley from the Salton Sea. We turned onto a small road lined with neat rows of stucco homes and cactus gardens, and after about a mile the road came to an end at two wooden gates.

The gates soared more than twenty feet high, with intricate carvings of flowers and birds rising up giant block letters at the top that read: PORCUPINE CREEK.

Jesse picked up his handheld radio. “Car three with Mr. Frank now at property,” he said.

A voice answered: “Entry granted, proceed.”

The gates swung open to reveal a lush, water-filled wonderland—a stark contrast to the parched desert we were leaving behind.

The freshly washed driveway was lined with tropical flowers, palm trees, and antique French streetlamps that had once lined the Champs-Élysées. Streams and waterfalls gurgled alongside the road. Birds sang, and teams of gardeners, all wearing matching white polo shirts and khakis, waved as we passed by. When we reached the top of the first hill, Jesse slowed down to offer a view of a nineteen-hole golf course stretching for 240 acres at the foot of the mountains like a vast green welcome mat.

“Does he live in a golf community?” I asked Jesse.

Jesse laughed. “It’s his golf course.”

As I considered the practicality of owning and maintaining your own golf course in the middle of the desert, we pulled up to a circular driveway in front of an equally impressive display: a water fountain modeled after the famed Bellagio fountain in Las Vegas (“but bigger,” Blixseth insisted), shooting brightly lit arcs of water into the sky. Behind the fountain, the main house came into view—a sprawling Mediterranean mansion, rising over three stories with carved balconies, porticos, pillars, and large picture windows. It was lit by dozens of outdoor torches and surrounded by guest villas, pools, and gardens.

We pulled up to the imperial entry hall, where two life-size terra-cotta Chinese soldiers stood guard in front of a pair of bronze lions. The front door of the house opened, and out burst Tim—a smiling, compact man in a Hawaiian shirt and cargo shorts.

“Roberto!” he said, holding out a glass of Chardonnay. “Welcome to our humble abode. It’s not much, but we call it home.”

In 2006, Tim was little known outside a small circle of rich people in Palm Springs and California. But he was about to land on the Forbes list as one of the richest people in America, with an estimated net worth of $1.2 billion.

Tim and his outgoing blond wife, Edra, had made their fortune in timber and real estate. Their biggest trophy and their greatest source of wealth was the Yellowstone Club, a 10,000-acre private golf and ski resort nestled in the Montana Rockies that counted Bill Gates, cycling star Greg LeMond, and former vice president Dan Quayle as members, along with host of other recently rich corporate chiefs and finance executives. Officially, members had to have a minimum net worth of $7 million to join, but most were far richer, since they had to build a home at Yellowstone and buy land, which cost more than $2 million an acre. Once approved, they had the run of a golf course and ski area populated solely by fellow millionaires and billionaires. No one had to worry about the occasional non-rich interlopers you might encounter in, say, Aspen or Palm Beach. They enjoyed heated gondolas and CEO-friendly ski trails with names such as “Learjet Glades” and “EBITDA” (a corporate term that means “earnings before taxes, depreciation, and amortization”).

The Yellowstone Club was a huge success. By 2006, plots of land were selling for five times their original price. The club not only made Tim and Edra rich but also turned them into the unofficial innkeepers of the new elite, as they hosted the ultra-wealthy of Silicon Valley, Hollywood, Wall Street, and Washington. Porcupine Creek boasted wall after wall of photographs of the Blixseths with George Bush, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Gerald Ford, Mariel Hemingway, and other notables.

Their lifestyle was unapologetically excessive, even by the standards of the mid-2000s. They owned two yachts, three private jets, two Rolls-Royce Phantoms (his and hers), seven homes, a private island in the Caribbean, and a castle in France.

Porcupine Creek’s staff of 110 maintained the home like a five-star resort. There was a kitchen staff of twelve manning five kitchens. There were towel boys by the pool, and waiters and chefs near every table or patio. One day, Tim was driving me around the golf course when a waiter popped up from behind a hedge to refill my wineglass. There were caddies, masseuses, security guards, drivers, gardeners, and technology experts to attend to every need.

They had a clubhouse with men’s and women’s locker rooms, a pro shop, and an equipment room—even though the Blixseths were sometimes the only players on the course, accompanied by their dogs named Learjet and G2 (for Gulfstream).

Every guest room and bathroom on the property was stocked with new bars of soap and robes emblazoned with the house logo, a smiling brown porcupine.

When I asked Edra why she needed to run her house like a luxury resort, she was very matter-of-fact. “That’s the way we’ve always done things, with five-star standards. The employees were happy to have the jobs and we were happy to employ them. There was just never any thought to costs.”

Despite their imperial lifestyle, the Blixseths were friendly, funny, and fiercely driven. They threw epic parties, including $1 million weddings for their children and a $300,000 party for Tim’s fiftieth birthday featuring a “living time machine” of famous rock bands and fashions from the past half century.

They were embodiments of the American dream. Tim grew up poor in rural Oregon, with what he calls “a rusty spoon in my mouth.” He often tells the story of how other kids taunted him on the cafeteria line in high school: “Welfare kid, welfare kid!” Edra was a single mom at the age of seventeen and worked the night shift at a diner before she started her own business and eventually met Tim. Now they were billionaires, at least on paper.

The Blixseths were also typical of America’s twenty-first-century wealth boom, in which real estate tycoons, entrepreneurs, and financiers could make colossal fortunes almost overnight with the right mix of luck, hard work, leverage, and asset bubbles. In 2006, when I was searching for people to profile for my book on the new American rich, the Blixseths seemed like naturals. I spent three days with them as they flitted from house to house and jet to yacht, as well as countless hours with them in follow-up interviews.

One evening Tim leaned back on the couch on the deck of his yacht and poured himself a glass of Chardonnay.

“Boy, if my dad could only see me now,” he said. “He would never have dreamed I would have a life like this. It’s been a wild ride.”

As it turned out, the ride was about to get a lot wilder.

In the winter of 2010 I flew back to Palm Springs. But this time there was no Jesse or Range Rover or lemon-scented towels.

I climbed into my rented Hyundai and drove out to Route 111 toward the Blixseths’. When I reached the wooden gates, I pressed the call button on the intercom. A recorded voice crackled over the loudspeaker: “This is a special message from Verizon. The service to this telephone has been temporarily disconnected.”

I kept buzzing and kept getting the recording. A few minutes later I heard a golf cart buzz down the property driveway. The gates cracked open and out peered Edra, looking overtanned and overtired. Instead of her usual designer suit or skirt, she was wearing jeans and a sweatshirt.

“Hi there!” she said, beaming. “Welcome back! Sorry about the gate. They shut the phones off because I couldn’t pay the bill.”

Edra climbed into her muddy golf cart and told me to follow her to the house. “I’ll give you the tour. You won’t believe it. Or maybe you will. Did you ever see the movie Grey Gardens?”

We rolled our way up the driveway, which was littered with dead leaves and branches. The waves of flowers had turned into brown weeds, and the streams and waterfalls had all dried out, leaving trails of cracked concrete. The golf course had turned an anemic shade of yellow and was strewn with fallen palm branches. When we stopped to look out over the seventh hole, there was total silence. Even the birds had flown off to seek greener pastures.

As we reached the front of the house, the Bellagio fountain was now an algae-covered pool. The terra-cotta soldiers were still standing guard, but with the emptiness around them, they looked more like lost sentries who had somehow missed the order to retreat.

We made our way inside. The house looked frozen in time and caked in dust. The living room was still filled with burnished European antiques, brightly colored ceiling murals, French chandeliers, and photos of Edra with Hollywood celebrities and politicians. The home’s health spa, gym, chef’s kitchens, and regal dining room all looked just as they had four years earlier. The soap dishes were still filled with little soap cakes embossed with the smiling porcupine. But it was eerily still.

Edra had laid off the last of her household staff the week earlier. Keeping up 30,000 square feet of house was proving far too great a task for one woman. She shuffled around the house with a roll of paper towels and a bottle of Windex, wiping off the chairs and tables before she sat down.

We toured the garage, which once had housed the two Rolls-Royce Phantoms and the Aston Martin DB-9 that Tim gave Edra for an anniversary present. Now it housed Edra’s golf cart and a ten-year-old Mercedes.

In the living room, a large fish tank stood on the center table. During my previous visit, the tank had been the room’s shining centerpiece—a 100-gallon Technicolor panorama of coral, anemones, and rare tropical fish. Now most of the fish and coral were gone. All that remained were two clown fish swimming around a slab of concrete.

“What happened to the coral?” I asked Edra.

“It got repossessed,” she said.

Edra explained that a local high-end aquarium company used to come and clean the tank and provide the coral, shells, and other ocean-scene accessories for about $1,200 a month. But after three months went by without payment, they took their coral and shells back.

“At least they left me the fish,” she said with a smile.

As we sat down, Edra listed the other ways in which her life had changed. The Yellowstone Club had gone bankrupt and was sold, and she had filed for Chapter 7 personal bankruptcy. The Gulfstreams were gone, and she had auctioned off most of her jewelry and antiques. She and Tim were in the midst of a public and bitter divorce that had dragged on for more than three years, and most of her days were now spent in court or with lawyers, fighting off the dozens of lawsuits or investigations related to her financial collapse.

After decades of having her own household staff, Edra was doing her own cooking, cleaning, shopping, and driving.

“I just discovered this place called Marshalls yesterday,” she told me. “Amazing! I had never been there. It’s so cheap.”

Losing the jets was the hardest part. After giving up the Gulfstreams, Edra made her first commercial flight in more than twenty years, on a trip to court in Montana. “It was horrible,” she said. “The security search, it was demeaning. And I was late for the flight, but they wouldn’t hold it for me. When I finally got on a flight, I got stuck in the very back seat between two other people. Nightmare.”

As Edra and I walked back through the house, I stopped again at the fish tank. I flashed back to the boom times of 2006, when Tim and Edra had been on top of the world, among the four hundred richest people in America. They could fly on their Gulfstream 550 to their French castle for dinner and return for breakfast and golf with Bill Gates. Their staff was larger than the workforce of most businesses.

Yet by 2010, it all looked like another mirage in the California desert. The Edra I was standing next to was flat broke. Her phones had been shut off. Her staff was gone. The coral in her fish tank had been repossessed.

The Blixseths’ success, like so much American wealth at the turn of the twenty-first century, was built on an illusion.

Between 1990 and 2007, America experienced its largest wealth boom in history. By 2007, there were more than ten million millionaire households in America, and more than half a million households worth more than $10 million—more than double the numbers in 1990.

Never before had so many people become so wealthy so fast. The Gilded Age of the late 1800s and the Roaring Twenties in the early twentieth century may have created richer individuals relative to the economy, with John D. Rockefeller’s wealth equal to 1.5 percent of the entire U.S. gross domestic product (GDP), which would be equal to $210 billion today. Yet the Second Gilded Age of the 1990s and 2000s eclipsed all others when it came to the sheer number of new millionaires and billionaires. The combined annual incomes of the top 1 percent exploded to $1.7 trillion, greater than the annual GDP of Canada. Their wealth topped $21 trillion at its peak in 2007.

The soaring fortunes of the rich grew in stark contrast to the rising debts and stagnant wages of the rest of America. The rich seemed to have created a self-contained world of privilege and prosperity, with their own health care system (concierge doctors), education system (private schools), travel network (private jets), and language (“Have your family office call mine”). The American wealthy had created their own virtual country, a place I called Richistan.

In my book of the same name, I profiled the people, places, and status markers of this strange new land. I shadowed shampoo tycoons in Palm Beach, garbage-collection heiresses in California, and a Jewish Irishman in Texas who was using his tech millions to help the poor in Ethiopia. I chronicled the rising demand for everything from butlers and personal arborists to five-hundred-foot yachts and private jets equipped with alligator-skin toilet seats.

During the peak of the Second Gilded Age, in 2008, Richistan appeared unstoppable. The fortunes of the rich just kept climbing, becoming as monumental and seemingly permanent as the 30,000-square-foot fortresses they now called home.

They had achieved the economic version of escape velocity, breaking free of the usual financial forces of gravity that kept the rest of America on the ground and prone to downturns. Economists opined that if America had a crisis or recession, Richistan would barely feel the impact, like a G550 hitting a small air pocket, causing its well-heeled passengers to momentarily clutch their glass of ’86 Mouton to avoid a spill before resuming their ride at 40,000 feet.

Then, in 2008, Richistan panicked.

In the eighteen-month period between 2008 and the middle of 2009, the fortunes of the nation’s millionaires fell by about a third—marking the greatest one-time destruction of wealth since the 1930s. The population of American millionaires plummeted by more than 20 percent, effectively wiping out five years of growth. Richistan’s lofty incomes also came tumbling down.

In percentage terms, the losses at the top surpassed those of any other income group in America. Incomes for the top 1 percent of earners fell three times as much as they did for American earners as a whole. The biggest losers were the super-earners, or those in the top one-tenth of 1 percent, who make $9.1 million or more per year. This elite group saw its income drop more than four times the average fall in the United States. As we will see, some of the wealthy—like Edra Blixseth—experienced almost unimaginable falls, as their net worth went from hundreds of millions of dollars to zero.

We shouldn’t shed any tears for the expatriates of Richistan. Giving up their Gulfstreams and poolside waiters may qualify as emotional trauma for people like Edra Blixseth. Yet their fall to mere affluence is proof that all suffering is relative. As millions of non-rich Americans lose their jobs and homes, many of the rich are already recovering from the financial crisis, thanks in part to the government bailout of Wall Street and the Federal Reserve’s support of financial markets and cheap money. As a reader of my Wealth Report blog wrote: “The rich have gotten back what they lost and the rest of America is still in the purple fart cloud of the last bust.”

In fact, one of the lasting legacies of the Great Recession may be that Richistan was further removed from America. The stunning fall of the rich may have brought them momentarily closer to the non-rich. But Richistan seems more foreign than ever, as many Americans lose hope of ever getting rich themselves. In our post-TARP, deficit-ridden age, many see the rich as the winners in a zero-sum game of global wealth. Richistan and America are viewed more like Disraeli’s “Two Nations,” “between whom there is no intercourse and no sympathy, who are as ignorant of each other’s habits, thoughts, and feelings as if they were dwellers in different zones … and not governed by the same laws.”

Yet Richistan’s ups and downs reveal a much deeper and more important change in our economy and in American wealth today—one that was laid bare by the Blixseths and countless others. Today’s wealth is no longer secure or stable, but built on a global financial system that’s increasingly prone to sudden shocks, crashes, and bubbles. While those shocks may seem irrelevant and even amusing to the rest of us, they will increasingly reverberate through our financial and political life as the rich dominate more and more of the economy and funding for governments.

Rather than viewing the financial crisis as a narrow escape for the rich, it may have been a warning that the worst is yet to come.

For the past eight years, I’ve been the wealth reporter for the Wall Street Journal, covering the lives and economy of the rich. I don’t carry a flag in the class wars. I’m not out to celebrate or castigate the rich, or to write a partisan polemic (there are already plenty of those). My aim is to report on the world of wealth just as I covered foreign countries as an overseas correspondent—describing the facts and details on the ground to readers far away.

If I follow any faith, it is the guidance of the economist John Kenneth Galbraith, who wrote, “Of all the classes, the wealthy are the most noticed and the least understood.” As our economy becomes increasingly dominated by the wealthy—by their incomes, their spending, their taxes, and their political influence—the rich merit understanding beyond the size of their mansions and private jumbo jets. We need to understand the basis of their fortunes, the deeper economic forces that lifted them to the top, and the changes that wealth has brought to their lives and values. By following the trajectory of the rich, who increasingly shape the direction of the rest of the country, we might be able to get a clearer picture of our own financial and political path.

In that spirit, I started reporting on the serial blowups of the super-rich during the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009. There were the Madoff victims, of course. And there were entrepreneurs such as the Bucksbaum family, whose shopping mall fortune plunged more than 95 percent, from $3 billion to about $100 million. Bankruptcies among the formerly rich reached all-time highs.

These weren’t the usual stories we associate with wealth loss—the financially challenged lottery winners and extravagant celebrities who blow their windfalls on binges in Las Vegas and Ferraris for their friends. The big losers in 2008 and 2009 were self-made businesspeople who were supposed to know a thing or two about money.

As fascinating as they were, however, the tales of extreme financial loss didn’t seem to merit a book. They were more like the Bugatti crashes that have become popular on YouTube—spectacular displays of wealth destruction that made for great schadenfreude but had little long-term meaning.

Then I discovered two remarkable charts.

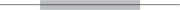

They were created by Jonathan Parker and Annette Vissing-Jorgensen, both economists at Northwestern University, using data from the Internal Revenue Service. The charts showed the gains and losses of various income groups dating back to World War II.

Here is the first chart, which shows incomes during expansions for all taxpayers and for the top 1 percent:

As you can see, the top 1 percent did far better than the rest of America during the recent boom times, telling the well-known story of rising inequality and the outsize gains of the few at the top.

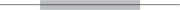

Here is the other, more important chart. It shows the relative income losses during downturns:

The chart shows that the top 1 percent led the country in income losses during the past three recessions. In the most recent downturn, the incomes of the elite sank more than twice as much as the rest of the country’s.

Even more intriguing was the history of those losses. The chart suggests that the Great Recession was not, in fact, a one-off. It was the latest in a series of escalating income shocks that led to huge spikes and crashes in the incomes of the wealthiest Americans.

These serial crashes were different from the more traditional ebbs and flows of American wealth, where old money was shoved aside by the nouveaux riche and large fortunes usually took a lifetime (or even generations) to dissipate. These new cycles of wealth were much faster and more extreme. Rather than taking three generations to make and lose a fortune, as expressed in the old adage of “shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations,” today’s rich were completing the cycle in a decade or less.

Risk has always been the handmaiden to large wealth. And there have always been rich people who look far richer than they really are, embodied by the saying “all hat and no cattle.” Still, the outsize losses and gains of the wealthy marked something new in our economy. For nearly four decades after World War II, the top 1 percent was the steady line on America’s income chart, gaining less and losing less than the rest of America during economic cycles. In the early 1980s—1982, to be precise—the top 1 percent broke away and became the most unstable force in the economy.

The research put the recession and the wealthy in a new light. An elite that had once been models of financial sobriety suddenly set off on a wild ride of economic binges. The trusty “millionaires next door,” with their rusty Ford pickup trucks, cheap suits, and hypercautious savings habits, had been eclipsed by a strange new personality type in the world of wealth. They were more manic in their earnings and spending, and they were by-products of a new system of financial incentives that rewarded extreme risk-taking, borrowing, speculation, and spending.

I call them the high-beta rich. In financial markets, the term high-beta usually refers to a stock that experiences exaggerated swings relative to the broader market. Tech stocks and start-ups, for instance, usually have a high beta. The high-beta rich had become like the human tech stocks of our economy, prone to violent swings and rapid cycles of value creation and destruction.

To me, this new personality type and the changing character of American wealth have largely gone undiscovered. This book aims to chronicle the rise and occasional fall of the high-beta rich and how they impact the rest of us.

The rise of the high-beta rich is important for three reasons.

First, the losses of the rich offer important lessons for all of us. While the story of getting rich has become a tired cliché in American culture, from Horatio Alger to Mark Zuckerberg, tales of losing large wealth are more rare but arguably just as important. Losing large amounts of wealth can offer a fresh perspective on what really matters in life. Without the trappings of money and power, the rich sometimes gain a better appreciation of their true friends, of their work or their passions, and of their connections to other people and communities—all of which can be obscured by wealth. They learn how quickly the things that once seemed so important (from jets and mansions to lavish parties and social status) can quickly vanish.

For some, of course, going from riches to rags is a nightmare from which they hope to awaken. They just want their jets and parties back. Yet to others, it is a crash course in learning to live more with less.

We can also gain financial wisdom from the fall of the rich. Since we often learn best from extremes, stories of radical wealth loss can show us how to better manage and perserve our own finances—from controlling our spending and understanding our investments to preparing for a crisis and borrowing money. (Lesson One: You’re only as smart as your debts).

In the coming chapters, you’ll meet a midwetern excavator who became a millionaire and found his dream retirement, only to be forced to sell his Florida estate at the bottom of the market. Today he lives in a truck. You’ll meet a family who built the biggest house in America, then ran out of cash and had to put the house up for sale. We will learn more about Edra Blixseth and her astonishing journey from billionaire to bust.

Along the way, I’ll ask questions both serious and trivial. What happens to the rich when they lose the money that defines them? If money can’t buy happiness, does losing great wealth make us happier or twice as miserable? How does someone employ, let alone fire, a household staff of 110 people?

The second reason we should care about high-beta wealth is because it reveals a new and untold side of the American upper class. The stereotypes of today’s rich usually include fat-cat Wall Street bankers who never miss a bonus, or thrifty small-business owners who scrimped and saved their way to wealth. Both types exist, of course. But today’s wealthy are wilder and more diverse than ever. Most of the super-rich made their money by starting and selling a company. Others became millionaires by running a publicly traded company or rising to the top of their field in law, medicine, science, or entertainment. Yet the rich today have one thing in common: their wealth is increasingly linked to financial markets, either through the companies they started and sold, or through huge salaries paid with shares or options. The way to get super-rich is no longer by making things or owning a family business, but from stock, deals, financial engineering, and “liquidity events.” These cash windfalls make entrepreneurs and financiers fabulously wealthy, but also make them vulnerable to booms, bubbles, and busts.

In the coming pages, you’ll meet two brothers who grew up on the cargo docks of New Jersey and became billionaires from building up their family shipping business. Even the toughest dock workers in New Jersey, however, couldn’t prepare them for the wealth managers of Wall Street and the hundreds of millions of dollars they lost in just a few months. You will meet a family whose fortune started with a flock of German canaries and grew to include a real estate empire and hedge fund, showing how wealth has migrated from the real to the financial.

We will also see how the wealthy are borrowing and spending more than ever before, projecting an image of success in front of a mountain of debt.

Behind their new Feadship yachts, Bentleys, and Tudor-tropical mountain ranches, many of today’s rich are only one crisis away from losing it all. They form a Potemkin plutocracy ever fearful of being exposed. In the next chapter, you will meet the grim reaper of this overextended overclass: a luxury repo man who nabs private jets and yachts that are in financial default. These stories challenge our perception that it is only the middle class and poor who binged on debt and who are susceptible to downturns.

The third and most important reason to learn about high-beta wealth is its impact on our future. The growing gap between the rich and the rest, with America’s top 1 percent controlling more than a third of the country’s wealth, means that the wealthy have growing economic influence and power—a trend well documented in books such as Wealth and Democracy, by Kevin Phillips; The Winner-Take-All Society, by Robert H. Frank (no relation); and Winner-Take-All Politics, by Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson.

The rise of high-beta wealth introduces a new side effect of inequality: With the growing dominance of the rich has come growing contagion from their financial manias. In the coming pages, we will see how high-beta wealth is wreaking havoc on the consumer economy, our financial markets, and even state governments. You will meet an economist who worked for the California state government and tried for years to warn politicians about the state’s dangerous dependence on the volatile incomes of the rich. When his warnings were ignored, California fell into its worst budget crisis in history, due in large part to the evaporating incomes of the state’s tech tycoons.

You will see how the spending of the rich has become five times more volatile than their incomes. As the wealthy account for more and more of our economy, with the top 5 percent of American earners accounting for 37 percent of consumer outlays, the American economy will also experience more extreme cycles. You will see the human impacts of this high-beta spending, including an unemployed butler who was forced to hang up his silver tray when his millionaire employer had to downsize.

We shouldn’t feel sympathy for the roller-coaster rich. But we should worry for the rest of the country. If the national risks of high-beta wealth had a simple equation, it would look like this:

America’s dependence on the rich + great volatility

among the rich = a more volatile America.

As go the high-beta wealthy, so goes the rest of the country. While trickle-down economics may be widely dismissed as a myth, I will show in the following pages how trickle-down losses are already becoming a reality.

To research this book, I interviewed more than a hundred people with net worths (or former net worths) of $10 million or more. While the people I’ve profiled are among the most colorful and interesting in the group, they are representative of the larger sample in their experiences and perspective. The profiles are based on on-the-record interviews with each subject (some totaling seventy hours or more over the course of two years) as well as secondary reporting and research.

We begin our journey with an economic species normally seen in low-income neighborhoods or lurking behind suburban garages after midnight. He is the repo man.