14

The Twentieth Century

If the nineteenth century was the Great Century for Protestant missions, the twentieth century could be called the tumultuous century. Missions agencies and missionaries faced many challenges and trials during this eventful period. Thankfully, many factors aided missionaries as well.

Hindrances to Missions in the Twentieth Century

World Wars

Only four years after the excitement and enthusiasm of the Edinburgh conference, World War I broke out in Europe. Eventually, the fighting spilled over into the Middle East and East Africa. The war lasted from 1914 until 1918. It affected missions in three primary ways. First, the war cost the lives of a generation of young men in Europe. The loss of life in the war was appalling, and many young men who might have become missionaries died in the battles. Second, the war burst the bubble of optimism that characterized Europe and North America at the turn of the century. The belief in the inevitability of human progress went down in flames like one of the new fighter planes on the western front. And, third, the war distracted the church from fulfilling its missions mandate.

World War II began in Asia in 1936, when Japan invaded China, and in Europe in 1939, when Germany invaded Poland. Historians often write that this war was really a continuation of the first, and that is true. The peace settlement negotiated at Versailles in 1918 sowed the seeds for the larger war that followed twenty years later.

World War II proved to be a truly global conflict. The navies of the Axis and the Allied nations fought on every ocean. Armies battled in China, the South Pacific, the Philippines, Southeast Asia, Burma, North Africa, Russia, and both eastern and western Europe. The war had both negative and positive effects on missions. Negatively, the war disrupted missionary work. Missionaries could not travel to many nations. Second, many young men who might have gone as missionaries served in the military. Third, many missionaries became caught up in the conflict and found themselves captives, interned in concentration camps for years. This was true of many of the missionaries in China, the Philippines, and Southeast Asia. Some of them spent four long years in Japanese prison camps. Fourth, many churches and institutions were destroyed or damaged in the fighting, not to mention the congregations that were scattered.

World War II also affected missions in positive ways. Soldiers, sailors, marines, and air force personnel traveled all over the world to serve their countries. As these young men and women visited faraway places, they saw the spiritual and physical needs of the people. The Lord laid these needs on the hearts of many, and they vowed to return to preach the gospel and heal the sick. Second, the war disrupted the status quo in many cultures, providing missionaries with an opportunity to present the gospel to people who wondered whether their old ways and old gods were still valid.

The Great Depression

The Great Depression was an economic disaster that affected the whole world from 1929 to 1941. The New York stock market crashed in October 1929, banks failed, companies declared bankruptcy, and millions of workers lost their jobs. Severe droughts plagued the midwestern region of the United States, compounding the financial miseries of millions of people. The Great Depression deprived mission boards and missionaries of the funds they needed badly. For example, the Foreign Mission Board of the Southern Baptist Convention set its budget for 1930 at $1,390,000. By 1932 the board reported receipts of only $691,302. All the mission boards suffered the same kind of decline in income. Many missions agencies went into debt in order to keep their missionaries on the field. When those efforts failed, many missionaries were called home because the mission boards could not afford to remit their salaries. Some missionaries stayed on the field and functioned as tentmakers, living as best they could. The number of new missionaries being appointed dwindled to only a few. Faith missionaries often sought in vain for supporters to help them meet their required support level. Beyond these problems, there was no money for capital projects such as buildings or equipment. President Franklin Roosevelt tried to alleviate the effects of the Great Depression with the social programs of his New Deal, but the United States did not pull out of the Depression until 1941, when American industry geared up for war production.

The Bolshevik Revolution occurred in Russia in 1917. By the time the civil war in Russia ended, the Communists had seized control of the government. Under the cruel rule of Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin, the church in Russia was severely persecuted and restricted. The Communist government desired to make the Soviet Union an atheistic state. The Soviet victory in World War II brought the Iron Curtain down on eastern and southern Europe. The Christians there suffered the same fate as those in Russia. Missionary activity basically ended, as well as the publishing and distribution of Bibles and Christian literature. The Communist governments imprisoned many pastors, outlawed evangelism, and oppressed Christians in many ways. For example, the Communist governments refused to grant Christian young people admission to universities.

When the Chinese Communists won the civil war in China in 1949 the Communist Party became the dominant force in that country. The new government expelled the missionaries and closed most of the churches, permitting only a few to remain open in large cities. Many Chinese pastors suffered greatly in “reeducation camps.” The government closed Christian institutions or converted them to state institutions. Some churches remained open, but under Mao Tse-tung the churches were highly regulated and restricted. The government consolidated all the churches into one organization they called “The Three-Self Patriotic Church.” The Communists chose that name to emphasize that the churches in China were no longer under the control of Western missions.

Because they could no longer worship in church, Chinese Christians met in home fellowships away from government oversight. These house churches grew and multiplied, especially during the disastrous Cultural Revolution of the 1960s. Eventually, networks of house churches developed, and the number of Christians grew rapidly after 1980. The number of Christians in China today is difficult to ascertain, but some estimate the number in 2005 at one hundred million. The deinstitutionalizing of the Chinese church may well have been an Acts 8 experience. Saul meant to destroy the church, but he actually caused the church to spread and grow. Similarly, the Communists meant to destroy the church in China, but they actually caused it to prosper. By closing institutions and churches, they forced the Chinese church to adopt a New Testament pattern of operation.

Theological Issues

Theological issues, particularly universalism and pluralism, affected missions negatively, especially in the Western mainline Protestant churches. Universalism is the belief that ultimately everyone will be saved. It takes several forms, but the most common is based on a view of God’s love: God is viewed as too loving to send anyone to hell. As more denominations and seminaries embraced universalism, the motivation to do and support missions declined precipitously. For example, the number of missionaries deployed by the two denominations that became the Presbyterian Church-USA declined from 1,713 in 1961 to 463 in 2003. In the United Methodist Church, the numbers were similar. During the same period the number of missionaries deployed by the theologically conservative Assemblies of God increased from 812 in 1961 to 1,880 in 2001.

Pluralism is the concept that all religions are equally valid ways to God. This idea became very popular after 1960. It expressed acceptance of other cultures and “toleration,” the dominant social value of the age. The question of how these different religions with their competing truth claims could all be true seemed not to trouble those who believed this idea.

The denominations whose leaders accepted these doctrines gradually reduced their missionary forces. The missionaries who remained on the field shifted their attention from evangelism and church planting to humanitarian activities. Beyond this change, these doctrines seemed to sap the mainline denominations’ enthusiasm for evangelism and church growth. Mainline Protestant churches in the United States have experienced steady declines in membership since 1960.

Nationalism

Nationalism is the feeling of love and devotion people have for their nation. If a nation’s population has too little loyalty, it is difficult for the nation to function. If a nation has too much, it can degenerate into a situation like that of Nazi Germany during the time of Adolf Hitler. So, nationalism is essential in moderation and dangerous in excess.

After World War II a number of nations gained their freedom from colonial powers. The Philippines gained its independence in 1946. India and Burma followed in 1947. In 1957 Ghana became the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to achieve independence. Nigeria, the most populous country in Africa, was granted self-rule in 1960. The period from 1945 to 1965 saw many nations establish new national governments. The impact of nationalism on missions varied widely. In the Philippines and Nigeria, missionaries continued to function as they had under the colonial powers. In other countries, though, major changes took place. Burma (now called Myanmar) expelled all foreign missionaries in 1966. India gradually placed more restrictions on missionaries, basically eliminating missionary visas. Many newly independent nations viewed Christianity as a Western religion closely identified with colonialism. Therefore, when they escaped the control of colonialism, they sought to limit the influence of Christianity as well.

Resurgent Islam

At the time of the Edinburgh conference in 1910, Islam seemed to be in a slow decline. Since 1950, however, Islam has made a remarkable comeback. There are three primary reasons for this. First, many Muslim nations gained their independence after 1950. This freedom allowed them to limit or eradicate the influence of Christianity in their lands. Many mission schools, hospitals, orphanages, and so on were closed or converted to government or Islamic institutions. The new governments expelled the missionaries who had entered these countries under colonial administrations. Second, the development of oil fields in many Muslim nations provided ample money for Muslim schools and missionaries. Many Muslim missionaries have been trained, especially in Saudi Arabia, and dispatched around the world to teach Islam to unbelievers and to inspire greater piety among Islamic populations. In addition, governments in the Middle East have built schools and provided free or inexpensive education for poor children in many underdeveloped countries, particularly in Africa. They have also provided funds for the construction of mosques and Islamic education centers at universities. Many bright students from Africa and Asia have received scholarships to study in the universities of the Middle East. Third, the twentieth century witnessed a revival or renewal within Islam. This has expressed itself most dramatically in the rise of Muslim fundamentalism. Muslim fundamentalists resent the encroachment of Western culture and values into their societies. They desire to purge their societies of these Western influences and to return to the pure Islam taught and practiced by Muhammad. This could be called a Muslim restorationist movement.

Materialism

Materialism is the worship of or devotion to material things. It is often said that materialism has more adherents than any world religion. Materialism distracts Christians from doing God’s will and obeying his word. It causes people to be indifferent to the gospel of Christ. Materialism affects giving to missions in that Christians are more concerned about taking a vacation cruise than funding a new missionary or more interested in acquiring a new sports car than contributing to the purchase of a new vehicle for a church planter. As American Christians have become more materialistic, per capita giving to missions has decreased. James Engel has documented this in his disturbing study titled A Clouded Future? Advancing North American World Missions (1996).

Localism

Localism is an excessive concern for local people and activities. The motto of localists is “Charity begins at home.” Often localists have little knowledge or concern for the world. They focus their attention on their church and their local community. This trend has affected missions dramatically. Churches in North America are keeping more of the funds they receive, and they are sending less to missions. For example, Southern Baptist churches give to missions weekly through the Cooperative Program, a kind of united fund for the denomination. Thirty years ago the average church gave 12 percent of its undesignated gifts to the Cooperative Program. Today the average church gives 6 percent. This trend has been seen in other denominations and independent churches as well. More and more churches have focused on local concerns, and the needs of missions and missionaries have gone unmet.

Though we listed hindrances to missions first, many factors have served to help or advance the cause of missions in the twentieth century. These include the following.

Improved Transportation

When William Carey and his family traveled to India in 1793, the voyage by sailing ship took about six months. By 1900 missionaries traveled by steamship, and the voyage took two or three weeks, depending on the number of stops along the way. By 2000 missionaries traveled by jet airplanes and complained if their journey lasted more than thirty hours. The dramatic improvements in transportation have meant that missionaries could get to their fields of service much more quickly, surely a better stewardship of time. Beyond that, improved transportation has meant that missionaries can be more mobile, ministering in multiple locations. Many missionaries now carry on a mobile training ministry, teaching short-term classes in many locations in the course of a year. Such a ministry would have been impossible a century earlier. Improved mobility has made it possible for mission administrators to visit the fields and their missionaries more often. This provides for better supervision and lower missionary attrition. The improvements have also made it possible for missionaries to return home for significant family events, such as weddings and graduations, as well as crises, such as the death of a family member.

Improved Medical Care

An earlier chapter mentioned the terrible loss of missionaries in West Africa between 1850 and 1910. The average duration of missionary service at that time was three years. The missionaries either died or returned home, too ill to continue in Africa. As tropical medicine improved, so did missionary longevity. Now, when missionaries go to West Africa, they receive a battery of vaccinations—nine or ten. Now a missionary’s death due to tropical disease is unusual, even newsworthy. Much of this improvement in tropical medicine is due to the work of Dr. Walter Reed of the Army Medical Corps in Cuba during the Spanish–American War. He discovered that mosquitoes carry yellow fever. This breakthrough led to many other discoveries and to improved medical care.

Missionaries today not only have the advantage of vaccinations but they also receive improved medical care on their fields of service. Of course, this varies widely from place to place, but the medical care available now cannot be compared to the paucity of care available to missionaries in 1800.

When the twentieth century began, missionaries communicated mainly by letters, sometimes by telegrams. As the years passed, more missionaries were able to use the telephone to stay in touch with one another, their supervisors, and their families. In the last years of the century, the internet and cellular telephones made communication much easier. Now, missionaries can stay in touch almost constantly with their colleagues and loved ones. This improvement in communication has affected missions in several ways. First, it has enabled missions agencies to modify their organizations. In many agencies several layers of administration have been removed because field supervisors can communicate more freely and quickly with missionaries. Second, improved communication has made the agencies more responsive. They can react to changing situations more rapidly. And, third, missionaries can monitor situations involving their children or aging parents more efficiently. Communication technology has changed so rapidly that it has jumped several technological generations. It is a strange experience to visit West Africa and observe a man talking on a cell phone in a village where there is no electricity. Typically, missionaries can purchase a cell phone, and the service begins immediately. Contrast that advantage with landline phone service. In some places missionaries had to wait for years for landline telephone service.

Specialized Missions

The twentieth century witnessed the establishment of many specialized missions agencies. During the nineteenth century, most missionaries concentrated on evangelism and church planting. The twentieth century saw the number of missions agencies increase dramatically. Many of these focused on a specialized aspect of missions. In fact, it could be said that specialized missions is an important characteristic of twentieth-century missions, and in chapter 16 we will explore these in greater detail.

The specialized missions undertook broadcasting, missionary aviation, disaster relief, tribal work, student work, and literature ministries. This is not to say that mission boards that maintain varied ministries disappeared. Still, the trend in missions after World War II was definitely toward specialized missions. This shift occurred in part because of the growing sophistication of technology. Another motivating factor was the conviction that some essential ministries had been neglected by broad-spectrum mission boards.

Some of the more prominent specialized missions agencies included the Wycliffe Bible Translators (1934), the New Tribes Mission (1942), the Missionary Aviation Fellowship (1945), and Campus Crusade for Christ (1951). These and many others sought to focus their efforts on one thing that they could do better.

The twentieth century was in many ways the technology century. Early in the century radio was introduced. Missionaries soon grasped its potential for mass evangelism overseas. Missionaries began broadcasting the gospel from missionary radio station HCJB in Quito, Ecuador, in 1931. Other powerful radio stations followed. Missionaries also used motion pictures to capture audiences and communicate the gospel. Television is a costly medium to use, but missionaries used it extensively after 1950, especially in urban areas. Satellite television makes it possible to transmit a Billy Graham Crusade service all over the globe. Further, using satellite television, missionaries can beam gospel programs into countries closed to missionary presence and activity.

The invention of the audiocassette enabled missionaries to record music, stories, teaching, sermons, and Bible passages and to duplicate those cassettes for the masses. This enabled missionaries to communicate to many more individuals, families, or listening groups than they could personally. When videocassettes became available, missionaries used them to penetrate homes and nations that were inaccessible to ordinary missionary activity. The distribution of The Jesus Film and The Passion of the Christ on video and DVD has significantly affected evangelization in many countries, especially Muslim nations.

The invention of computers has also aided missions. Computers have made it possible to develop databases of information about ethnolinguistic groups, languages, and many other categories essential to missionary work. Beyond that, computers have cut in half the time required to complete the translation of the Bible into a given language. Of course, computers are essential to the internet and email. Through websites, much information on missions has been made available to students, supporters, and missionaries alike. Web posting is much cheaper than publishing books or journals. It also can be accomplished much more quickly. This interchange of information and resources helps missionaries work more quickly and effectively. There is less “reinventing the wheel.” Computers have also made missionary mapping much more accurate. Combined with the use of Global Positioning System (GPS) devices, missionaries can produce more accurate maps, showing the locations of people groups.

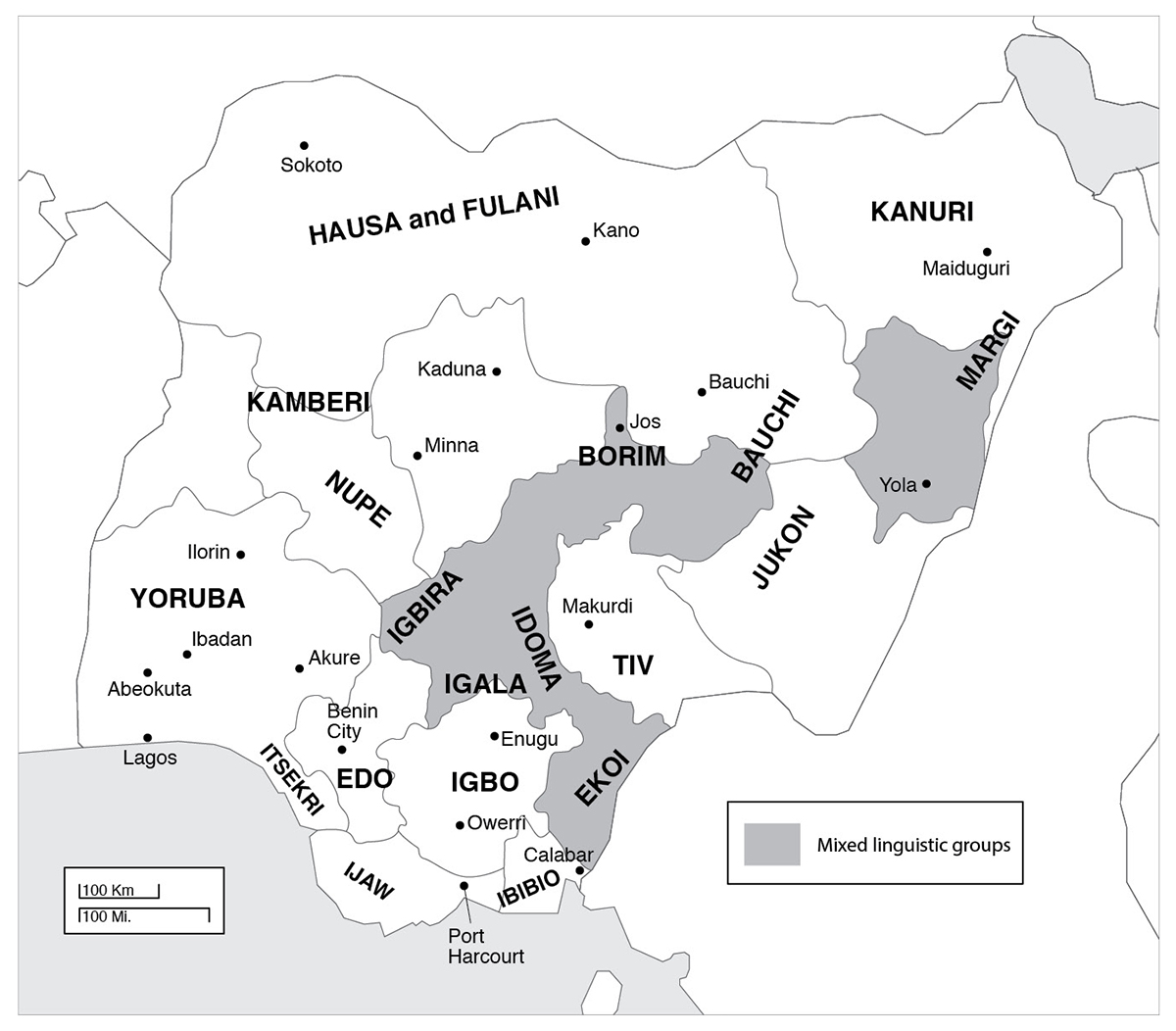

Map 14.1 People Groups in Nigeria

Anthropology

Anthropology is the study of humans, especially human cultures. One of the social sciences, anthropology began to be taught late in the nineteenth century by E. B. Tylor and J. G. Fraser. Margaret Mead did much to enhance the acceptance of anthropology as an academic discipline. Eugene Nida of the American Bible Society began to lecture widely on linguistics and cultural anthropology and their application to missiology. His book Customs and Cultures was one of the first textbooks on missionary anthropology. William Smalley did much to advance missionary anthropology through his writings and Practical Anthropology, a journal that he edited. These two men slowly convinced evangelicals that missionaries needed to know more than Bible and theology in order to be effective field-workers. Donald A. McGavran emphasized the social sciences in his missions philosophy, the church growth movement. When he founded the School of World Mission at Fuller Seminary in Pasadena, California, he enlisted Allen Tippett to serve as professor of anthropology. More recently, Paul Hiebert and Charles H. Kraft have written helpful, popular books on missionary anthropology. Today anthropology is accepted as a required subject in missionary training. The result of anthropology’s acceptance has been two generations of missionaries who were more cognizant of and sensitive to the cultures of the peoples they served. Anthropology has also enabled missionaries to present the gospel in more understandable and contextualized ways. Through anthropology, missionaries have been able to minimize the effects of culture shock, an occupational hazard for cross-cultural workers.

Improved Linguistics

Linguistics is the social science that studies languages. During the twentieth century this subcategory of anthropology made great strides. Through the efforts of gifted linguists such as Kenneth Pike, the application of linguistics to Bible translation both improved and sped up Bible translation work. As a result, missionary Bible translators produced better translations and completed them more quickly. Improved knowledge of linguistics also helped missionaries learn their adopted languages better and more quickly. Donald Larson and Thomas Brewster contributed much to this effort.

The Progress of Missions around the World

Missions to Muslims

Muslims represent the largest unreached population in the world. In 2004 demographers estimated their number to be 1.3 billion. Because Muslims maintain a high birthrate, this number seems likely to increase considerably in the twenty-first century. Missionary work among Muslims goes back to Ramon Llull in the thirteenth century. Henry Martyn and others did admirable work in the nineteenth century, but the twentieth century witnessed a great swell in missionary work among Muslims. This was especially true when the focus of missions shifted to the 10/40 Window.

Missions to Muslims represents a great challenge, not only because of their numbers but also because of their resistance to conversion. The obstacles to evangelization can be categorized as historical, theological, cultural, and political. Historical obstacles include the Crusades of the Middle Ages. Westerners may view the Crusades as ancient history, but Muslims do not. For Muslims the Crusades happened last year, and they engendered an antipathy that continues until today. The historical and continuing support of the American government for the state of Israel causes many Muslims to resent the United States. They identify Christianity with the United States, so they see Christian missionaries as agents of American imperialism. Finally, evangelical mission boards and missions agencies generally neglected the evangelization of Muslims throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Of course, some denominational and faith boards gave special attention to missions to Muslims, but the percentage of missionaries working among Muslims was low in proportion to their population.

A whole book could be devoted to the theological obstacles to evangelizing Muslims. Muslims reject the incarnation, atonement, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. They believe that the Gospel accounts were corrupted and present a distorted picture of Jesus. The contention that God could have a son is a great blasphemy in the thinking of Muslims, and they categorically reject the doctrine of the Trinity. In fact, they contend that Christians are actually polytheists, while they are the true monotheists. Muslims believe in sin, but they reject the doctrine of original sin. Most Christians, especially Americans, value the concept of the separation of church and state, but Muslims, for the most part, desire complete integration of religion and government.

Cultural obstacles also make missionary work difficult. Western missionaries have typically emphasized individual salvation, while religion for Muslims is much more closely tied to family and community. It is quite difficult for a Muslim to make an individual decision apart from the approval of his or her family. Muslims who come to Christ face familial, social, economic, and government persecution. Further, identifying with Christianity is seen as identification with Western culture. In many Islamic nations to be a loyal citizen is to be a faithful Muslim.

Legal obstacles complicate mission work in several respects. In Islamic countries it is against the law for a Muslim to change religion. Such conversion is considered apostasy, and in some countries it is a capital crime. In other countries apostasy is punishable by imprisonment. Most Muslim countries refuse visas to missionaries, making it hard for missionaries to enter. In most Muslim countries it is illegal to witness to a Muslim, and these governments refuse Christians’ requests to do mass evangelism or gospel broadcasts. In Saudi Arabia the only legal church is one for foreigners in an oil-company compound. In other countries, such as Egypt, churches are permitted, but their activities are restricted.

Through the years missionaries have employed many different models or approaches to the evangelization of Muslims. Many early missionaries used the confrontational approach to evangelism. These missionaries sought to win Muslims by public debate and disputation. They challenged the veracity of the Qur’an and questioned the prophethood of Muhammad. Ramon Llull, Henry Martyn, and Karl Pfander used this approach. They preached publicly in the bazaars. They produced apologetic and polemical literature in English and in the local languages. This approach never prompted much response. It garnered few converts and often increased antipathy toward Christianity. In the twentieth century it was used only in places where colonial governments could protect the missionaries from violent reprisals.

The spirit of Christ is the spirit of missions. The nearer we get to Him, the more intensely missionary we become.

Henry Martyn (https://home.snu.edu/~hculbert/slogans.htm)

Samuel Zwemer, “the apostle to the Muslims,” used an approach that might be called the traditional evangelical model. Through preaching, teaching, personal witnessing, and literature, Zwemer and others sought to communicate Jesus Christ to Muslims. They tried to win Muslims and gather the converts together into Western-style churches. Often, these missionaries practiced “extraction,” removing converts from their homes, neighborhoods, and even countries in order to minimize the possibility that the convert would recant. This model was used throughout most of the twentieth century, but it, too, proved unsuccessful. The missionaries saw few conversions and few churches planted. The missionaries for their part acknowledge the meager results, but they insist that their method is biblically sound and should continue to be used, hoping and praying that obstacles will one day be removed.

The institutional model became popular early in the twentieth century. Presbyterians, Congregationalists, and Reformed churches gave special emphasis to Muslim missions, especially in the Middle East. They sought to win Muslims through hospitals, schools, and orphanages. These mission boards recognized that Muslims are suspicious of or even antagonistic toward Christianity; therefore, they sought to remove these prejudices by institutional demonstrations of love, compassion, and service. Indeed, in some countries institutions were the only way a mission board could establish and maintain a presence. In many places the institutions did make some converts, and in all cases they won the respect of the local people. Still, this model has been used less in recent years. The governments in many Islamic nations have assumed control of these mission-sponsored institutions. Also, economic inflation has made the funding of these institutions problematic, not to mention the difficulties involved in maintaining staff levels.

The dialogical model became popular in the early twentieth century. Temple Gairdner (1873–1928) pioneered this approach, and Kenneth Cragg developed it more fully. Dialogue has taken two forms, an ecumenical form and an evangelical form. The ecumenical form seeks dialogue that will result in mutual respect and theological compromise—a synthesis of concepts. The evangelical form seeks dialogue with Muslims based on mutual respect. The missionaries sincerely want to establish rapport, exchange views, and bring their Muslim friends to faith in Christ. The ecumenical approach had no impact on the evangelization of Muslims. The evangelical approach has proved helpful, and it is certainly culturally appropriate. Many Muslims enjoy discussing and debating religion, so this approach builds on that cultural trait.

Phil Parshall developed the contextualized model in his missionary work in Bangladesh. In this model the missionary seeks to become like the local people in order to present the gospel in culturally relevant forms. This approach is cognizant of the “offense of the gospel,” but it does attempt to remove as many objectionable practices as possible. This model suggests changes in missionary lifestyle (dress modestly, do not eat pork), worship forms (meet on Fridays, leave shoes at the door), theological terms (refer to Jesus as Isa), and missionary strategy (wait to baptize until several converts are ready).

Parshall described his approach in his book New Paths in Muslim Evangelism (1980). In more recent years, other missionaries have adopted a more radical approach to contextualization that they call C-5 and C-6. Writing under pseudonyms in the Evangelical Missions Quarterly (Travis 1998, 404–17), these missionaries have advocated encouraging Muslims who accept Christ to remain in the mosque and in their communities, witnessing to their faith in Isa as they have opportunity. Parshall and others have expressed concerns about the more radical approach, fearing that syncretism will be the result.

Through the efforts of Zwemer and others, some Protestant churches were started in Muslim lands, but their numbers were scant. In fact, only a few Christians could be counted in most Islamic nations. Only three significant Muslim people movements to Christ can be cited in the twentieth century. In Indonesia, the nation with the largest Muslim population, the Communists attempted a coup in 1965. Their attempt failed, but during the harsh reprisals by the government, many Indonesians became Christians, especially on the island of Java. Some estimate that as many as one million became Christians. In North Africa a significant people movement developed among the Berber people between 1980 and 2000. In the last years of the century, a people movement began in south Asia that shows great potential, claiming five hundred thousand believers at the time of this writing.

In the last two decades of the century, many more missionaries were appointed to Muslim people groups, especially in central Asia. Much of this effort was in response to the emphasis on the 10/40 Window. With this new emphasis and an increased missionary force, the twenty-first century may witness a great turning to Christ by Muslims. This hope is spurred by new missionary methods such as Chronological Bible Story Telling (see Tom Steffen’s Reconnecting God’s Story to Ministry [1996] for an introduction) and the Camel Method (Greeson 2004), which seem to hold promise for increased effectiveness in evangelism.

East Asia

East Asia includes China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and Mongolia. China has been the focus of missions praying and doing from the beginning of the modern missions movement. This is due to its vast population, 20 percent of the world’s total, and its great influence throughout Asia. During the first fifty years of the twentieth century, missionaries in China experienced steady growth. There were local spiritual awakenings, but nothing on a national scale.

When the Communists gained control of the country in 1949, there were perhaps three million Christians in China, including Catholics and Protestants. The new government closed almost all the churches, which forced many faithful Christians to meet illegally in homes. Despite persecution, and perhaps in many ways because of it, these house churches prospered and multiplied.

Additionally, since the death of Mao Tse-tung, the Chinese government has allowed many former churches to reopen. Today the church in China consists of registered churches that operate openly under the auspices of the China Christian Council, unregistered underground house-church networks that operate illegally, and unregistered house churches that operate openly with the tacit permission of local authorities. The number of Christians is multiplying rapidly, especially in eastern China. Some speculate that the twenty-first century may be the century of the Chinese church (Phillips 2014).

Protestant missionaries entered Japan in 1859 and found some receptivity initially. The missionaries established Christian schools and colleges, and these proved effective in reaching Japanese youth. However, in 1890 the government severely restricted the religious education that mission schools could provide their students. Coupled with the declaration of Shinto as the state religion, this prohibition slowed the growth of Christianity considerably. World War II devastated Japan in several ways, and many Japanese turned to Christ during the period 1945–1955; however, after that time materialism and the influence of Confucianism and resurgent Buddhism seemed to negatively impact response to missionary activity. At the end of the twentieth century, less than 1 percent of the Japanese population was Christian despite more than a century of missionary activity.

The history of Christianity in Korea presents a very different picture indeed. Protestant churches in Korea grew steadily from their beginning in 1884. Presbyterians and Methodists gained the most converts in part because they entered Korea first, and also because they employed the Nevius method in their work. The indigenous approach proved effective among the industrious Koreans. More important than methodology, though, was the power of the Holy Spirit. The Korean church experienced a great spiritual awakening in 1905–1907. The revival in the churches of that era still reverberates today. One aspect of the revival was early morning prayer, which has become a hallmark of Korean Christianity. The close identification of the Protestant churches with the Korean independence movement gained the church social acceptance by the masses. Today, more than 25 percent of the population is Christian, and the church in South Korea is a leader in the sending of missionaries.

The situation in Southeast Asia varied greatly. Christianity first arrived in Southeast Asia when Magellan landed in the Philippines in 1521. The Roman Catholic Church established a strong presence throughout the islands, and the Spanish colonial government aggressively thwarted attempts by Protestant missionaries to enter. In 1898, after the Spanish-American War, the United States gained control of the Philippines. This opened the door for Protestant missionaries, and they flooded in. The growth of Protestant churches was slow and steady until World War II. After the war, the Philippines gained its independence, but the new constitution still provided for complete freedom of religion. Both nominal Catholics and tribal animists have readily accepted the invitation to come to new life in Christ. The postwar era saw a number of evangelical missions begin work in the islands. These included Southern Baptists, Conservative Baptists, New Tribes Mission, and the Overseas Missionary Fellowship. The Far Eastern Broadcasting Company set up transmitters that blanketed the islands as well as beamed programming all over Asia. Freedom of religion and the natural openness of the Filipino people have proven to be a beneficial combination for missionary efforts in the Philippines. Many Filipinos now serve as domestic and international missionaries, especially with the Summer Institute of Linguistics and Campus Crusade for Christ.

The situation in Indonesia varies from region to region. In formerly animistic areas, such as Irian Jaya, Christians are the majority, while in vast areas of Java and Sumatra, Islam holds sway. Some Islamic people groups contain only a few Christians. Christians of all types compose about 10 percent of the total population. In many areas Muslims have persecuted Christians, and this has been particularly acute in Ambon and northern Indonesia.

Missionary work in Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Myanmar (Burma) has been extensive but not very fruitful, at least among the majority populations. Generally, missionaries have experienced good responses among the animistic tribal people of the mountain areas, while the response of the lowland Buddhist majorities has been quite limited. Roman Catholics established a considerable presence in Vietnam because it was a French colony. The French government limited Protestant access for many years, but after 1920 the Christian and Missionary Alliance and Oriental Missions Society worked in Vietnam and Cambodia. Many missions agencies have worked in Thailand, which has been open to missionary presence, but, again, the response of the lowland Thai people has been quite limited. Response among the hill tribes has been much better.

In Myanmar, Christianity entered the country through the efforts of first the British and then the American Baptists. Adoniram Judson found limited response among the Buddhists, but his missionary associates found great response among the hill tribes. Today there are more than five hundred thousand Baptists among the Karen, the Kachin, and the Chin, among other hill tribes. Because these tribes have been fighting for independence from the central government, the government has oppressed the church in many ways. Response among the lowland Burmese Buddhists remains disappointing.

Singapore is a prosperous island nation. Christianity has made great gains among the Chinese population, especially the English-speaking Chinese. In Malaysia the Roman Catholic Church is the strongest church, although the Anglican Church and the Methodist Church also are strong. In recent years charismatic churches such as the Assemblies of God have seen much growth. Most of the Christians in western Malaysia are Chinese, while in eastern Malaysia tribal people are the majority among believers.

Africa

In 1900 Christians numbered roughly 7 million in Africa, while in 2000 the number had increased to almost 350 million. This dramatic growth represents one of the most interesting accounts in church history. In West Africa freed slaves who settled in Freetown, Sierra Leone, started churches up and down the coast and established a Christian training college, Fourah Bay College, in 1827. The Church Missionary Society established a strong base for the Anglican Church in Nigeria. Southern Baptists entered Nigeria in 1950 and planted many churches in southern Nigeria. The Sudan Interior Mission began work in Nigeria in 1893 and established the Evangelical Church in West Africa (ECWA). Presbyterians and Methodists planted many churches in Ghana, and that nation now boasts a Christian majority, though much nominalism is evident.

In East Africa the Anglicans also established many churches, particularly in Kenya and Uganda. The Africa Inland Mission began working in East Africa and established two well-known institutions, Scott Theological College, for the training of African workers, and Rift Valley Academy, for educating missionaries’ children.

In South Africa the Boer settlers brought with them the Dutch Reformed Church, which remains quite strong. Evangelical groups such as the London Missionary Society worked among the indigenous tribes and saw good results. When British settlers entered South Africa in 1820, Anglicans, Methodists, Presbyterians, and Baptists also entered. Methodists accomplished much among the black population. In recent times churches have labored to erase the ill effects of apartheid and achieve Christian unity. The increased freedom under the new regime has made possible the development of many independent churches, especially of the charismatic type. In recent years the churches of South Africa have deployed a number of missionaries around the world.

In central Africa the Roman Catholic Church has dominated in nations that once were colonies of Portugal and Belgium, such as Angola, Congo, and Zaire. Civil war in these countries has disrupted missionary work and brought incredible suffering to the people.

Independent churches became a hallmark of African Christianity. Because missionaries tended to be reluctant to yield control of the churches and denominations, Africans started churches on their own, apart from the influence of missionaries. These churches are known as AICs. Over the course of time, the acronym has stood for “African Independent Churches,” “African Indigenous Churches,” “African Initiated Churches,” and “African Instituted Churches.” Regardless of the exact word used for the “I,” AICs now number in the thousands and reflect a wide divergence in theology and practice. Some can scarcely be described as Christian, some are very evangelical, but the majority could be described as charismatic or Pentecostal.

India

Missionaries operated under the colonial protection of Great Britain during the first half of the twentieth century. After India gained its independence in 1947, the government gradually introduced more restrictions on foreign missionaries. This was partly due to nationalism and a natural reaction to colonialism. The restrictions also reflected the influence of Hindu nationalist politicians. According to the government, Christians comprise 3 percent of the population, though many Christian researchers believe the actual number is double that. Most of the Christians live in the southern states of India. The Indian church has shown great concern for evangelism and missions. A number of indigenous missions agencies have developed, such as the India Evangelical Mission, Gospel for Asia, the India Evangelical Team, and the famous Friends Missionary Prayer Band. These agencies and a host of others have deployed missionaries all over the subcontinent to evangelize and plant churches. Traditional mainline denominations have displayed a disappointing nominalism, much as in North America. Newer, charismatic churches have multiplied and grown considerably.

God Hold us to that which drew us first, when the Cross was the attraction, and we wanted nothing else.

Amy Carmichael (www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/missionary)

Europe

Western Europe was once the primary base for sending Christian missionaries. Sadly, that is no longer true. Ravaged by two destructive world wars and affected by secularism, Europe is now seen as the object of missionary endeavors. Though the state churches of Europe claim most of the population as members, only 3 percent of Europe’s population attends worship services on a regular basis. This has led many to call for a re-evangelization of Europe.

Eastern Europe was closed to missionary work for much of the twentieth century due to the influence of the Communist governments. When the Iron Curtain came down in 1989, missionaries and Christian organizations poured into Russia and eastern Europe. This proved to be a mixed blessing. Many missionaries and groups brought badly needed personnel and resources. On the other hand, the indiscriminant use of money and influence fostered financial dependency that inhibited natural, healthy church growth. The initial response to the gospel after 1989 was quite positive, especially in the nations of the former Soviet Union. After several years, though, materialism and the resistance of the governments and the Russian Orthodox Church negatively affected church growth. Poland stands out as a Catholic nation, and Romania shows promise of becoming an evangelical lighthouse in eastern Europe.

Latin America

In Latin America the Roman Catholic Church is the dominant religious force. In fact, about 50 percent of all Catholics live in the region. Still, during the second half of the century evangelical churches saw significant growth in many countries, especially in Brazil, Chile, Guatemala, and El Salvador. Much of this growth came in the Pentecostal/charismatic wing of Protestantism. Today many Latinos are going as foreign missionaries to Spain, Portugal, and North Africa, where they are serving with distinction.

At the end of the twentieth century, missions leaders could reflect on a remarkable century of progress. Though they did not achieve their ambitious goal of evangelizing all the peoples of the world by the year 2000, much was accomplished. According to David Barrett’s World Christian Trends, in 1900 there were 558 million people in the world who called themselves Christians, while in 2000 that number had increased to almost 2 billion. In 2000 Christianity was the largest religion in the world. Beyond that, the concerted efforts of evangelical missionaries brought the gospel to 58 percent of the world’s people groups, especially the larger, more populous groups, according to the Joshua Project website. Gospel radio broadcasts blanketed the globe, and the Bible was available in languages understood by 80 percent of the world’s population. In most nations the leadership of the church had passed to local leaders. Though much remained to be done, much had been accomplished. As Ruth Tucker has written, “The spread of Christianity into the non-Western world, principally as a missionary achievement, is one of the great success stories of all history” (2004, 480).

When Baptism Means Breaking the Law

Reprinted with permission from Hiebert and Hiebert (1987, 164–65)

Pastor Prabhudas was uncomfortably aware that Rukhmini’s eyes often fastened on him as she sat quietly in the corner of the front pew, awaiting the outcome of the church-council meeting. Somehow he felt she would hold him most responsible for the decision. But he said very little, allowing the elders to carry on the discussion.

All she wanted was for the church to baptize her on the confession of her faith. How ironic it was, he thought to himself. The church prayed often and hard for Hindu converts, especially from among the castes that have been almost entirely resistant to Christianity. Now that they had an authentic convert from a high caste, the council was thoroughly perplexed about whether or not to baptize her. If, like the vast majority of Christians, she had come from the “untouchable” portion of society, now called “scheduled castes” in deference to the reforms of Gandhi, they probably would have baptized her immediately.

Pastor Prabhudas remembered his own joy when Rukhmini had come to his office to ask about baptism. He had heard something of her story from her college friends who were members of his church, but he listened gladly as she told him about her life and her conversion to Christ.

Rukhmini told the pastor that she was the eldest daughter of poor but high-caste parents who had sacrificed and struggled to send her to college so that her job and marriage prospects would be enhanced. They saw this, in the traditional cultural way, as a means to gain more income to support themselves and their younger children.

Once in college, Rukhmini became friends with some Christian students. They gladly drew her into their circle, although no one put any pressure on her to become a Christian. One reason for their “Christian presence” style of witness was that it is against the law in the state of Orissa to make converts from other religions. It is punishable by imprisonment.

Nevertheless, Rukhmini saw something in these Christians that was very attractive to her. She noted the joy and peace in their lives and wished it for herself. After a while, she asked to go to church with them. There she heard the story of Jesus and accepted him as her Savior. The experience transformed her life. She began to study the Bible with her college friends and grew in her faith.

For a while, Rukhmini remained a “secret believer,” like other caste people, some of whom never take baptism because it would mean total ostracism from family and caste. In the case of a single woman like herself, it would mean that her parents could hardly find anyone to marry her, because there were so few Christian young men from the upper castes. No Hindu parents would give them a son, and for her parents to give her in marriage outside the caste would be unthinkable.

The time came, however, when Rukhmini decided that she could no longer hide her Christian faith. That was when she came to Pastor Prabhudas and asked for baptism. He had not tried to hide the consequences from her, and it became clear as they talked that she knew them only too well. Her parents would object strongly, and her disobedience to them would itself become a reason for criticism of Christianity. This would be seized upon by the local organization of the Hindu Samaj, who were fanatical in their opposition to Christians and used any breach of cultural norms to condemn them. And, of course, if it could be proven that the Christians had converted Rukhmini, the Samaj would bring a legal case against them. It was not unlikely that baptism of a high-caste woman would become an opportunity for persecution of the entire poor and largely powerless Christian community in that town.

Pastor Prabhudas had promised Rukhmini that she could put her request for baptism before the church’s council of elders. Now they had spent almost two hours discussing the issues and seemed to be no closer to a decision. Some of them thought the whole church should be involved; others thought the decision should be made here and now by the council. The pastor finally let his eyes meet those of the young woman who sat patiently waiting for them to arrive at some conclusion. He knew it was time for him to enter the discussion. Choosing his words carefully, he began to speak. . . .

Reflection and Discussion

- What would you advise Pastor Prabhudas to say?

- What creative solutions might you consider?