One summer day in Boston in 1761, John Wheatley, a prosperous merchant, and his wife, Susanna, arrived at a slave auction at Beach Street wharf. The Phillis, a slave ship that had traveled from an area near Gambia in West Africa, was docked there. Its human cargo was on the dock for all to see or buy.

According to the 1838 publication Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, a Native African and a Slave, Susanna Wheatley saw “several robust, healthy females” and could have bid on them, but her attention was caught by a slender, naked girl who was likely seven or eight since she was losing her baby teeth. Susanna was taken by the “humble and modest demeanor and the interesting features of the little stranger.” As suggested by Vincent Carretta in Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage, perhaps the girl evoked thoughts for Susanna of her own daughter, Sarah, who was almost that same age when she died on May 11, 1752. She chose the girl and named her Phillis Wheatley—Phillis for the ship, and Wheatley to match her own last name.

Library of Congress LC-USZC4 5316

Phillis was frail. Perhaps it was the result of conditions on the nearly eight-month voyage she made with the 75 other enslaved Africans—men, women, and children. Given her age and gender, Phillis would have been allowed to spend much of her time on deck to breathe fresh air because she posed no threat, while the rest of the time she and the others would have been in the dark hold of the ship, below deck, without sanitary facilities. Most likely she saw some of the men chained to the bottom or sides of the hold. When she went to sleep, she would have leaned on one of the other women, many would have been ill from the voyage. Had she died, she would have been tossed overboard.

Susanna Wheatley’s intention that day at the Beach Street wharf had been to select a young house servant. Her slaves were getting older and she, at age 52, was aging as well. Susanna introduced Phillis to her 18-year-old twin children, Mary and Nathaniel. In the weeks and months that followed, the family heard Phillis saying words in English. They saw her trying to write out individual letters—a or b or c—imitating what she saw Susanna or Mary or the others doing. Mary soon became Phillis’s tutor. Within a year and a half, Phillis was able to read complex passages from the Bible. She attended church at Old South Meeting House and later became a full member of that church.

Five years later, at age 12, Phillis was writing poems. Her first one was written to a minister of the Old South Meeting House. When she was 14 years old, her first published poem, “On Messrs. Hussey and Coffin,” appeared in the Newport Mercury newspaper on December 21, 1767. She was also studying religion with Rev. Dr. Richard Sewell, a man whose family was well known for its antislavery beliefs. While Phillis was a slave, she wasn’t living like most slaves but was more like a member of the Wheatley family. Susanna didn’t ask her to do many household tasks and intentionally kept her isolated from the other slaves.

Phillis later wrote of the dramatic events of her life and of her religious beliefs in a poem: “On Being Brought from Africa to America.”

’Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too …

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew, …

Phillis also used her poems to comment on the events occurring in Boston leading up to the American Revolution. One was a poem to King George III, ruler of Britain: “Rule thou in peace, our father, and our lord.”

Another poem, “On the Death of Mr. Snider Murder’d by Richardson,” criticized British actions in 1770 when 11-year-old Christopher Snider was killed when customs informer Ebenezer Richardson fired into a crowd: “With unexpected infamy disgraced / Be Richardson for ever banish’d here.”

When Phillis was 16 or perhaps 17, she wrote a poem on the death of Boston evangelist George Whitefield that brought attention to her talent as a poet. The notice prompted Susanna to take action to have Phillis’s poems published in a book. A prospective publisher, however, had some doubts, wondering if Phillis actually wrote the poems herself, without any help.

Again Susanna stepped in. She arranged for 18 prominent Bostonians to attest to her talent. The men included Governor Thomas Hutchinson, Lieutenant Governor Andrew Oliver, John Hancock, president of the Second Continental Congress and later a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and 15 others, most of whom were already familiar with her poems. The men agreed that, yes, Phillis was capable, and they believed her to be the author of her poems.

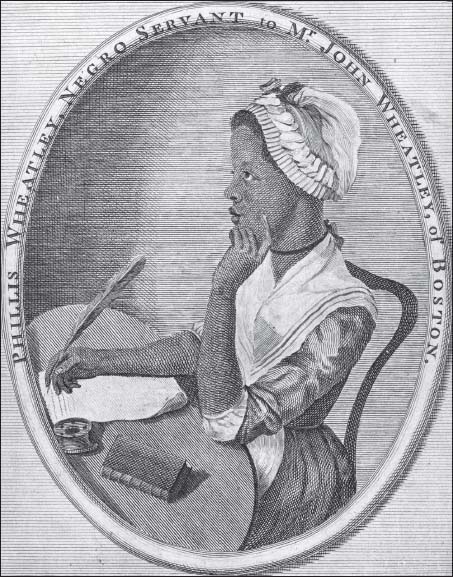

Susanna wanted to see Phillis’s poems in print and took the next step. She knew that if a book—any book—was dedicated to a person of importance, it could help with the book’s success. She asked Selina Hastings, the Countess of Huntingdon if Phillis could dedicate the book to her. Selina, impressed with Phillis’s poems, agreed and also agreed to become her patron and requested an engraving be done of Phillis for the book. It was presumed to have been done by enslaved African American artist Scipio Moorhead.

Susanna also placed ads in Boston newspapers telling of Phillis’s talent and of the upcoming book. Phillis, however, was ill, suffering from asthma, and the Wheatley’s family doctor thought an ocean voyage might improve her poor health. Since Susanna’s son, Nathaniel, was about to sail for London on family business, Susanna decided to send Phillis along on the voyage. It would give Phillis the opportunity to meet Selina Hastings and to be in London for the publication of her book. The Massachusetts Gazette and the Boston Weekly News-Letter of May 13, 1773, included the announcement:

Boston, May 10, 1773 Saturday last Capt. Calef sailed for London, in [with] whom went Passengers Mr. Nathaniel Wheatley, Merchant; also, Phillis, the extraordinary Negro Poet, Servant to Mr. John Wheatley.

In turn, the 20-year-old Phillis expressed her emotions about her failing health and Susanna’s sadness about the upcoming trip in “Farewell to America,” a poem she dedicated to Mrs. Susanna Wheatley.

I mourn for Health deny’d…

Susannah mourns, nor can I bear

To see the Christal Show’r

Fast Falling—the indulgent Tear

In sad Departure’s Hour.

When Phillis arrived in London, she was well received. She met with Benjamin Franklin, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence and Granville Sharp, a leader in the struggle to end slavery in Britain. She was set to meet with King George III and with Selina Hastings, her patron. She surely was looking forward to seeing her book in print, to looking at the words on the title page: Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral by Phillis Wheatley. It would be the first book published by an African American woman and only the second book published by an American woman.

Then Phillis received news that Susanna Wheatley was ill and wanted her to return immediately to Boston. Surely disappointed but concerned, Phillis boarded a ship that set sail for America.

In the meantime, when her book came out in London, it was an immediate success and was used as proof of the intellectual ability of Africans, an issue debated at the time.

Yet, despite the acclaim, Phillis was still a slave. Soon after the book’s publication and her return to America, the Wheatleys granted Phillis her freedom, though she continued to live with the family. She cared for the ailing Susanna for the next three months until she died on March 3, 1774, at the age of 65. In a letter to a friend, Phillis wrote:

Let us imagine the loss of a parent, sister or brother. The tenderness of these was united in her. I was a poor little outcast and stranger when she took me in; not only into her house, but I presently became a sharer in her most tender affections. I was treated by her more like her child than her servant.

Two months later, after Phillis’s return to Massachusetts in November 1773, 300 copies of her book arrived in America. All copies quickly sold. In June of the following year, the British blockaded the Boston Harbor and only one more shipment of her books arrived, somehow getting through the blockade. With the success of Phillis’s book, she became the most renowned black person in the colonies.

As Phillis, now a free woman, worked to generate income for herself by continuing to write poems, regiments of British troops landed in Boston and marched the streets. Ships of war arrived in port. And Phillis Wheatley, on October 26, 1775, then in Rhode Island, wrote a letter to George Washington, enclosing a poem that acknowledged the importance of his position. It ended with the lines:

Proceed, great chief, with virtue on thy side,

Thy every action let the goddess glide.

A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine,

With gold unfading, WASHINGTON! be thine.

When Washington received Phillis’s letter, he first put it aside, then later passed it on to his former military aide, Joseph Reed, on February 10, 1776, along with a note:

I recollect nothing else worth giving you the trouble of, unless you can be amused by reading a letter and poem addressed to me by Miss Phillis Wheatley. In searching over a parcel of papers the other day, in order to destroy such as were useless, I brought it to light again. At first, with a view of doing justice to her poetical genius, I had a great mind to publish the poem; but not knowing whether it might be considered rather as a mark of my own vanity, than a compliment to her, I laid it aside, till I came across it again in the manner just mentioned.

A few days later, Washington wrote to Phillis:

Cambridge, Mass.

February 28, 1776

Miss Phillis, Your favor of the 26th of October did not reach my hands, till the middle of December. Time enough, you will say, to have given an answer ere this. Granted. But a variety of important occurances, continually interposing to distract the mind and withdraw the attention, I hope will apologize for the delay, and plead my excuse for the seeming but not real neglect. I thank you most sincerely for your polite notice of me, in the elegant lines you enclosed; and however undeserving I may be of such encomium and panegyric, the style and manner exhibits a striking proof of your poetical talents; in honor of which, and as a tribute justly due to you, I would have published the poem, had I not been apprehensive, that, while I only meant to give the world this new instance of your genius, I might have incurred the imputation of vanity. This, and nothing else, determined me not to give it place in the public prints.

If you should ever come to Cambridge, or near headquarters, I shall be happy to see a person so favored by the Muses, and to whom nature has been so liberal and beneficent in her dispensations. I am, with great respect,

Your obedient humble servant,

GEORGE WASHINGTON.

That could have been the end of it: a private letter between one person and another. But Joseph Reed picked up the hint given him by Washington. He sent the poem and letter to the editors of the Virginia Gazette, and they were published on March 20, 1776. Thomas Paine, author of Common Sense, a document that inspired American patriots in 1776 to declare independence from Britain, republished the letter and poem in the April 1776 issue of a magazine called the Pennsylvania Magazine: or, American Monthly Museum.

As Phillis’s voice heralded Washington and the Revolution, her own life changed drastically. John Wheatley died at age 72, in 1778, and left her nothing in his will. Mary died soon after, and her brother, Nathaniel, had moved to London and died in 1783. She was on her own, without the support of family.

In 1778 Phillis married a freedman, John Peters, a grocer, and she continued to speak out in poetry. In one of the poems, “Liberty and Peace,” which she wrote under the name Phillis Peters, she wrote of the Peace of Paris, the set of treaties that ended the American Revolution. It ended with the lines:

Let virtue reign and thou accord our prayers,

Be victory ours and generous freedom theirs.

Phillis and her new husband had both been freed. Years earlier, in 1774, she had sent her thoughts on slavery in a letter to the Reverend Samson Occom. She wrote, “God has implanted a Principle which we call freedom; it is impatient of Oppression, and pants for Deliverance.”

Unfortunately, her new life came with challenges and heartbreak. Her husband, while initially prosperous, had financial problems due to the harsh economic situation after the war—which was especially difficult for freed African Americans—and was often in debt. Eventually Phillis and John lived in poverty. Phillis cleaned houses to help support them and persisted unsuccessfully in her efforts to find a publisher for her second volume of poems, which was never published and has not survived. While John and Phillis were reported to have had three children who died while very young, “no birth, baptismal, or burial records have been found for any of the children of Phillis and John Peters.” While John was imprisoned for debt in 1784, Phillis died at the age of 31, on December 5, probably as a result of chronic asthma.

Phillis Wheatley used her pen as her means of action in revolutionary America. She wrote of and for America, and her thoughts expressed in her poems still matter. Her voice is still heard.

Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage by Vincent Carretta (University of Georgia Press, 2011)

Phillis Wheatley Complete Writings by Phillis Wheatley (Penguin Books, 2001)

The Trial of Phillis Wheatley