Light-haired, blue-eyed Lydia Darragh edged her way through the crowded streets of Philadelphia in 1777, jockeying for position with the 14,000 British troops occupying the American capital of Philadelphia, a city of 23,000. None of them likely suspected her of being a spy.

George Washington’s Continental Army had been forced out of the city and was camped at Whitemarsh, 20 miles out of town. Philadelphia had been the capital of the new American nation, but the Continental Congress, the ruling body of the newly formed nation, had moved to Baltimore to avoid capture by the British.

Could Washington launch an attack, close off the city, trap the British, and regain the city? Maybe. Certainly he could benefit by knowing the plans of the British troops, and Lydia Darragh thought her son Charles, one of the soldiers camped at Whitemarsh, could help.

As she made her way through the city streets, perhaps to purchase flour from one of the mills on the outskirts of the city in order to make bread for her family, or to shop for meat or other things for her family, Lydia was surely alert to the conversations she overheard—comments like, “A number of troops have gone out of town,” or, “There is talk today, as if a great part of ye English army were making ready to depart on some secret expedition.”

After Lydia heard snippets like these, she told her husband, William, who had been the family tutor when she was growing up in Ireland. Lydia Barrington and William Darragh had married in Dublin, Ireland, on November 2, 1753, when she was 25 and he 34. They left Dublin behind, crossed the sea, and started their life together in Philadelphia. By 1777 they were the parents of five children.

William carefully wrote down in code the information Lydia shared with him, using symbols to represent words. When he finished, Lydia smoothed the paper, carefully molded it over a button, then covered the paper and button with fabric matching the coat of her 14-year-old son, John. After John put on the coat, he traveled to Whitemarsh, surely passing British soldiers on the way, until he reached the Continental Army camp and found his older brother, Charles.

Charles knew the routine, removed the fabric, translated the message from shorthand back into letters, and delivered the information to General Washington’s headquarters.

Lydia Darragh’s spy ring was quite a clever way of contributing to the war effort from a woman who, only 10 years prior, had posted an ad using her needle and thread skills in a very different way:

The Subscriber, living in Second street … takes this Method of informing the Public, that she intends to make Grave Clothes, and lay out the Dead, in the neatest Manner … she hopes, by her Care, to give Satisfaction to those who will be pleased to favour her with their Orders. Lydia Darragh.

During the years of 1777–1778 when the British Army occupied Philadelphia, British officers took over many of the homes in town, and those Philadelphia families had to find other places to live. General Sir William Howe, commander of the British Army, had taken over one house and made it his headquarters. The Darraghs lived in a building known as Loxley’s House on South Second Street.

One day William Darragh answered a knock on the door. The soldier on the step informed him that the family must find a new home because the British wanted to take over their house. When Lydia heard that news, she decided to visit British headquarters to speak with General Howe. As she waited, she began chatting with one of the British officers and discovered his last name was Barrington, the same as her maiden name. Soon Lydia and the officer discovered they were indeed from the same part of Ireland, and were second cousins!

Headquarters of British commander General Sir William Howe.

The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution by Benson J. Lossing, 1860

Loxley’s House, the residence of the Darragh family.

The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution by Benson J. Lossing, 1860

Perhaps struck by the serendipity of their connection, the officer listened as Lydia told him of the difficulty of finding a home for her family in the already crowded city. He spoke to General Howe for her, and a compromise was reached. Lydia, William, and the children could stay in their home but had to give up a large room at the back of the house that British officers could use for meetings—a council room.

Officer Barrington and General Howe might have been swayed in Lydia’s favor when discovering that the Darraghs were Quakers, a religious movement whose members declared themselves to be neutral in times of war. Of course, with a son in the army and with an active button-related spy system already in place, Lydia had broken with Quaker beliefs, but her reputation as a Quaker may have convinced the British military men to trust her.

Lydia and William took one action in response to the British setting up a council room in their house. They sent their two youngest children—William, 11, and Susannah, 9—to live with relatives outside of town.

In the days and weeks that followed, British officers came and went through the Darragh home, walking to and from the back room. An account published in 1827 by Lydia’s daughter Ann, who was 21 at the time and residing with her mother, tells of the events that followed. (Ann’s account was told to and recorded [on an unknown date] by Lydia’s great-granddaughter, Margaret Porter Darragh, for the family history.)

According to Ann’s account, the British officer who made arrangements for use of Lydia’s back room told her “to have all her family in bed at an early hour, as they wished to use the room that night free from interruption.”

That was on December 2, 1777. As Lydia lay in bed, thinking of that comment, she slipped out of bed and “into a closet, separated from the council room by a thin board partition covered with paper, just in time to hear the reading of the minutes of the council.” She heard that the British troops were going to attack “Washington’s army, and with their superior force and the unprepared condition of the enemy victory was certain…. A sharp pang shot through her heart.”

According to Ann’s account, Lydia then quickly returned to her bed and pretended she was fast asleep when the British officer knocked on her door once, twice, to let her know of their departure. On the third knock, she answered as if just having awoken. As he exited, Lydia put out the lights and locked the outside door.

The next day, according to Ann, Lydia spent her day thinking of what to do with the information. She didn’t choose to relay it via buttons, but she did devise a plan. That night, she told William that she would use an old pass—Philadelphians needed passes in order to leave the city during the British occupation—to visit their younger children who lived outside the city. It’s also said that she told William she was planning to go to a mill outside the city limits to buy flour.

Either way, she walked toward Whitemarsh by herself and, according to Ann, “did not tell her husband the real reason for her errand to the country until she thought the danger was over…. She feared the least suspicion of his having taken information out of the city might endanger his life.”

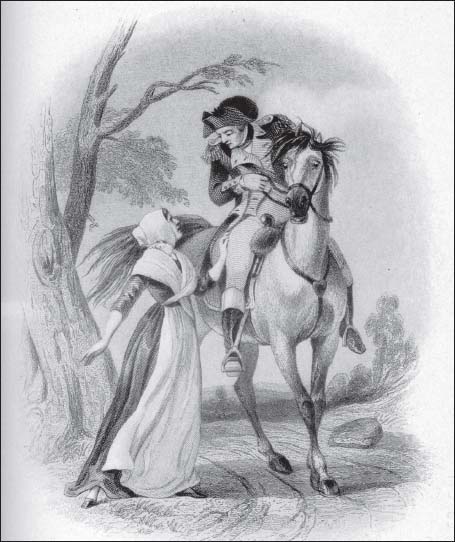

On her way Lydia saw an American officer approaching on horseback. They recognized each other. Captain Craig of Washington’s army “was greatly surprised to see her,” Ann recounted, “and asked, ‘Why, Mrs. Darragh, what are you doing so far from home?’ She asks him to walk beside her, which he does, leading his horse. In low tones she tells him the important intelligence she has risked so much to bring, and he at once rides with it to headquarters.”

Lydia probably didn’t know that others were also passing on information about British plans to those in Washington’s army. Bits of information about troop movements were trickling in from a variety of sources. Many people suspected something was about to happen. But when?

Captain Craig left Lydia, then made his way to the Rising Sun Tavern, where Colonel Elias Boudinot, who managed the intelligence for the Continental Army, was having dinner. Craig passed on the information to Boudinot. Yet Boudinot made a curious entry in his journal:

In Autumn of 1777 the American Army lay some time at White Marsh. I was then Commissary Genl of Prisoners, and managed the Intelligence of the Army. I was reconoitering along the Lines near the City of Philadelphia. I dined at a small Post at the Rising Sun ab’t three Miles from the City.

After Dinner, a little, poor looking, insignificant Old Woman came in & solicited leave to go into the Country to buy some Flour. While we were asking some questions, she walked up to me and put into my hands a dirty old Needle-Book, with various small Pockets in it—Surprised at this, I told her to retire—She should have our Answer—On opening the needlebook, I could not find anything, till I got to the last Pocket, where I found a piece of paper rolled up into the form of a Pipe shank—on unrolling it I found information that Genl Howe was coming out the next morning with 5,000 men, 13 pieces of cannon, baggage wagons, and 11 Boats on Waggon Wheels.

Lydia Darragh passing secrets.

Pioneer Mothers of America by Harry Clinton Green and Mary Wolcott Green, 1912

Was Lydia that old woman? Some say she was. Others suggest Lydia gave the information to another woman to deliver for her. According to one account, Colonel Craig took Lydia to a farmhouse along the road to rest and have something to eat and then, as suggested by Melissa Lukeman Bohrer in Glory, Passion, and Principle, Lydia could have given the information to a woman at the farmhouse who then passed it on to Boudinot.

Or perhaps Lydia delivered the information twice—once to Colonel Craig and then again to Boudinot—to make sure it got to Washington. Boudinot’s account continued:

On comparing this with other information, I found it true and immediately rode Post to head Quarters—According to my usual Custom & agreeable to Orders recd from Genl W. I first related to him the naked Fact without comment or Opinion—He rec. it with much thoughtfulness—I then gave him my opinion, that General Howe’s Design was to cross the Delaware under Pretense of going to New York—Then in the Night to recross the Delaware above Bristol & come suddenly on our R, when we were totally unguarded.

Lydia returned to the mill that afternoon, picked up her bag of flour, and returned home in early evening. When General Howe and the British troops approached Washington’s camp the next day for a surprise attack, the Americans had their cannons mounted and troops ready. The British had to turn around without attacking.

A victory for Washington! But for Lydia? Later that day, the officer who had asked Lydia to have her family go to bed early only two nights before knocked on her door and, according to Ann Darragh’s account,

called her to the council room and then locked the door. She was so faint she would have fallen if he had not handed her a chair and asked her to be seated. The room was nearly dark, and he could not see the pallor of her face. Then he inquired if any of her family were awake on the night of their last council. She replied: “No, they were all asleep.” Then, he said: “I need not ask you, for we had great difficulty in waking you to fasten the door after us. But one thing is certain; the enemy had notice of our coming, were prepared for us, and we marched back like a parcel of damned fools. The walls must have some ears.”

Later, in relating the story to her friends and family, Lydia said, “I never told a lie about it. I could answer all his questions without that.”

On December 10, six days later, George Washington wrote to the president of the Continental Congress, Henry Laurens: “In the course of the last week, from a variety of intelligence, I had reason to expect that General Howe was preparing to give us a general action.”

Due to the publication of Ann Darragh’s account of her mother’s activities as a spy, Lydia’s story was celebrated by schoolchildren until 1877, when a man named Thompson Westcott challenged the story on a number of points. His arguments were included in the American Quarterly Review of 1827 and reprinted in the Evening Bulletin of 1909 along with the statement: “The story has been discredited.” Westcott argued that Washington already knew of the impending attack, that Lydia didn’t have time to walk there and back.

But in 1915 a man named Henry Darrach (no relation) countered Westcott’s arguments in a publication by the City History Society of Philadelphia. The story of Lydia Darragh’s delivery of information to George Washington continues to be doubted by some but believed by most.

Lydia and her family continued living in Loxley’s House. In June 1778 the British left Philadelphia and moved to New York City. After the death of her husband on April 22, 1786, Lydia moved to another home in Philadelphia, where she lived and ran a store until she died on December 28, 1789, at the age of 61.

Glory, Passion, and Principle by Melissa Lukeman Bohrer (Atria, 2003)

Contains a chapter on Lydia Darragh

“Lydia Barrington Darragh (1728–1789)”

National Women’s History Museum

www.nwhm.org/education-resources/biography/biographies/lydia-barrington-darragh

Publications [or Publication] of the City History of Philadelphia (Published by the City History Society, 1917)

Available on Google Books

Contains a chapter on Lydia Darragh by Henry Darrach

Women and the American Revolution by Mollie Somerville (National Society, Daughters of the American Revolution, 1974) Contains a chapter on Lydia Darragh

Women of the American Revolution (Vol. I) by Elizabeth F. Ellet, contains a chapter on Lydia Darragh (spelled Darrah).

http://archive.org or Google Books