The British were coming! But 16-year-old Sybil Ludington couldn’t have known it was happening. It was 4:00 in the afternoon of April 25, 1777. Sybil might have been helping her mother prepare supper, feeding her horse, Star, or interacting with her seven younger brothers and sisters—Rebecca, 14, Mary, 12, Archie, 9, Henry, 8, Derick, 6, Tertulus, 4, and Abigail, 1.

Sybil, born April 5, 1761, couldn’t have known that 20 transports and six war vessels carrying 2,000 British troops had sailed into Long Island Sound and dropped anchor in the mouth of the Saugatuck River in Compo, just 30 miles from the home where she lived with her family in Fredericksburg, New York.

Colonel Henry Ludington, Sybil’s father, couldn’t have known it was happening either. Or that General William Tryon was leading the troops. Colonel Ludington had served under him during the French and Indian Wars when he was fighting for the British. Now Henry Ludington was on the other side, one of those fighting for independence from the rule of England’s King George III.

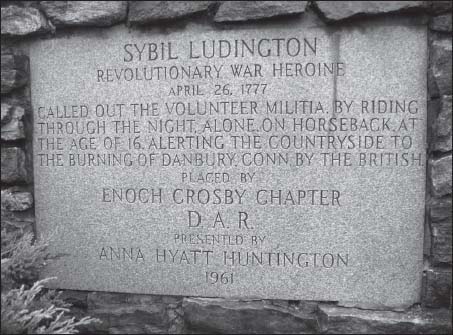

Sybil Ludington Monument (Carmel, NY).

Photo by Susan Casey

At the start of the Revolution, Ludington was aide-de-camp to General George Washington. Later he became commander of a militia of 400 men in western New York, where he lived. He didn’t know he’d be called on to lead his men to fight against the arriving troops. Neither did Sybil.

As a commander, Colonel Ludington was important to the Revolution. The British offered a reward for his capture, dead or alive. Many Tories wanted to collect the reward, so the colonel and the entire family, living on a farm in the countryside, had to be on guard. Sybil (whose name is sometimes spelled Sebal or Sibbell), the oldest of his eight (at the time of the ride and 12 in all) children, was often his sentinel.

One night when Sybil and her younger sister Rebecca were standing watch, guns in hand, they discovered that a group of Tories had surrounded the house. Fearful but quick-thinking, Sybil and Rebecca quickly roused their four brothers and two other sisters, gave them candles, and told them to walk back and forth in front of the windows in every room in the house. The moving silhouettes created by the candlelight gave the Tories the impression that the house was heavily guarded, so they didn’t dare attack. Sybil and her sister had outwitted them.

While Sybil couldn’t have known about the present danger only miles from her home, locals near the shore, hidden behind trees and rocks, watched the British soldiers—some in red coats with epaulettes, some in bright yellow breeches and black boots—exit the ships, get into formation, and march north led by General Tryon, formerly the royal governor of New York, and his assistants, Generals James Tanner Agnew and William Erskine.

The locals might not have known where the troops were headed or what they planned to do but they surely understood that something was bound to happen. A messenger hurried to alert General Gold Selleck Silliman, who lived in Fairfield and was in command of the militia in that part of Connecticut. Silliman sent news to General David Wooster and General Benedict Arnold, both in New Haven, to bring their troops to meet him. Couriers were sent to nearby towns to alert them, and a messenger on horseback trod through heavily wooded terrain to tell Colonel Ludington to gather his militia to join the defense.

Silliman at first guessed that the troops planned to attack Redding, Connecticut, 13 miles north. He gathered his men and headed in that direction. That guess turned out to be wrong. The British continued marching north and camped for the night in Weston, about eight miles north. Any local who guessed that their true destination was Danbury, Connecticut, a town of about 400 homes roughly 20 miles north of the shore, would have been right.

In the morning the British continued on with no resistance, intent on arriving in Danbury to destroy the supplies the Revolutionary Army stored there, including 5,000 pairs of shoes and stockings, a printing press, hospital bedding, thousands of bushels of grain, hundreds of barrels of beef and pork, and more than 1,000 tents. Loss of the supplies would be disastrous to the Revolutionary forces. Without them, how could they wage war against the British? That’s why Tryon wanted to destroy them.

The next day—Saturday, April 26—the British troops made their way closer to Danbury where men, women, and children were fleeing town, fearful of what the approaching troops might do to those loyal to the Revolution. Some pulled oxcarts and wagons filled with their possessions along rutted roads out of town. Some hid in the woods or in barns. Others secreted horses and cattle in the nearby forests. Some hid their young sons because of rumors that the troops had plans to kill young boys before they could grow up to be soldiers. Some stayed in town to guard their homes.

Danbury needed a defense. Only 50 Continental Army soldiers usually guarded the town, but they were away. A militia of only 100 men was no match for the thousands of troops marching toward them. While every family had a musket, many were torn between defending their families or the town. Those loyal to the king, the Tories, stayed put.

The sun was shining as the British troops reached Danbury between 2:00 and 3:00 on that Saturday afternoon. General Tryon wasn’t hesitant about settling in. Since he planned to stay the night, he first took over a house, that of Nehemiah Dibble, as his headquarters.

Generals Erskine and Agnew, riding their horses on Main Street, flanked by many other mounted soldiers, were looking for quarters for themselves when, according to History of Danbury, Connecticut, 1684–1896 by James Montgomery Bailey, an older man named Silas Hamilton, worried about the fate of a bolt of cloth he’d left at a town shop, raced on his horse to the shop in hopes of retrieving it. Perhaps he was fearful that the shop would be burned by the British troops. He dismounted, ran into the store, and then ran quickly out, cloth in hand. Silas mounted his horse and held the reins with one hand and the bolt of cloth with the other as he was quickly pursued by a halfdozen troopers. One of the troopers shouted and swung a sword at him. Silas, surely terrified, lost his hold on the cloth and it unraveled, flying out behind him, scaring the pursuing horses and allowing him to safely ride away.

Others in Danbury were not so lucky. When four young men hiding in a house fired on the troops, the building was torched and the men inside died. As other British troops reached the courthouse, they discharged their artillery, sending heavy cannon balls flying up the street, terrifying families hiding in their homes.

The British had made their point. When troops found supplies in several buildings, locals didn’t try to stop them. One building full of stored grain was burned to the ground. Another that contained barrels of meat was set on fire and “fat from the burning meat ran ankle-deep in the street.”

In late afternoon, storm clouds filled the sky and it began to rain, a condition that surely complicated the journey of troops led by Generals Silliman, Wooster, and Arnold and muddied the roads traveled by the messenger on his way to the Ludington farm.

At around 9:00 PM the messenger finally arrived at the Ludington farm and greeted Colonel Ludington with the news that the British were burning Danbury. The messenger told him to muster his militia, a task that Ludington knew would take hours. The 400 men in his militia regiment had earlier returned home to plant their spring crops. Their farms were widely scattered across miles and miles of the countryside. It would take hours to rouse them. How could Colonel Ludington do it himself and be at his home to organize the men when they arrived? He turned to the exhausted messenger for help, but the messenger told him he was too tired to go. According to Willis Fletcher Johnson in his 1907 book, Colonel Henry Ludington: A Memoir,

In this emergency, he turned to his daughter Sybil, who, a few days before, had passed her 16th birthday, and bade her to take a horse, ride for the men, and tell them to be at his house by daybreak. One who even rides now from Carmel to Cold Spring will find rugged and dangerous roads with lonely stretches. Imagination only can picture what it was like a century and a quarter ago, on a dark night.

Sybil mounted her horse, Star, surely watched by Colonel Ludington and the messenger as she departed. Though it was raining, her way was lit when the moon shone through the storm clouds.

It was a dangerous mission, an almost 40-mile ride. Thieves and ruffians were known to be in the forests, waiting to steal from or attack those who passed. As the rain beat down, Sybil must have feared for her safety as she steered Star alongside the middle branch of the Croton River on the way to the town of Carmel. When she arrived she gave the warning: “The British are burning Danbury!” The village bell began ringing to alert the town militia to muster. “Tell them to join my father at Ludington’s Mill,” she said, and off she went along the paths edging Lake Carmel, then along the shore of Lake Gleneida. She banged on the doors of the scattered farmhouses with a stick, telling each person who answered the same message: “The British are burning Danbury. Join my father at Ludington’s Mill. Tell your neighbors.”

As Sybil rode on, the British troops continued their assault on the supplies stowed in Danbury. In one building they found bottles of wine and rum. Before torching the building, they began drinking the spirits. Not long after:

the greater part of the force were in a riotous state of drunkenness … the drunken men went up and down the Main Street in squads, singing army songs, shouting coarse speeches, hugging each other, swearing, yelling, and otherwise conducting themselves as becomes an invader when he is very, very drunk…. The carousers tumbled down here and there as they advanced in the stages of drunkenness.

Fearful townspeople peered out their windows at the chaos.

Meanwhile, Sybil, still traveling on the narrow paths through the forests and past the dark farm fields, was most likely having a harder time of it. Most people had extinguished the lights in their homes. She would have had to be cautious in steering Star and on guard against cowboys and skinners who were known to hide in the woods to rob or even kill those who passed.

Meanwhile, in Danbury, General Tryon, who had planned to stay the night and “spend the Sabbath leisurely in Danbury,” was at his quarters when he got news around 1:00 in the morning on April 27 “that the rebels under Wooster and Arnold had reached Bethel,” which was only three or more miles away. He ordered that the drunken and sleeping men be roused.

Yet he didn’t order his troops to leave town. Instead he ordered them to go about destroying their foe. Houses marked with a cross, the indication that the occupants were Tories—supporters of the British—were passed by and others randomly burned. “Flames seemed to burst out simultaneously in all directions…. An old lady afterward said that if she had not been so frightened, she could have put out the newly kindled fire with a pail of water.”

As 19 homes as well as some stores and shops burned, the sky turned orange. Could Sybil see the flames lighting up the sky as she raced through the countryside, continuing on to Kent Fields and then to Redding Corners, enduring the rain, the darkness, the fear of attack, and her own fatigue? By then, militiamen she had summoned had begun arriving at Ludington’s Mill.

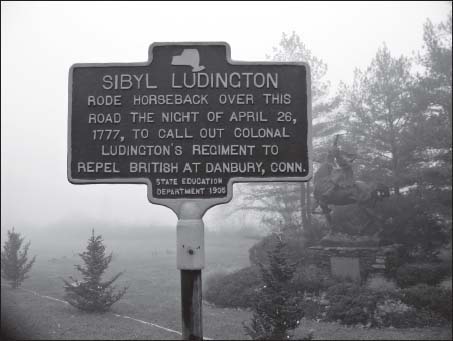

Signs mark the route taken by Sybil Ludington.

Photo by Susan Casey

In 1935 the New York State Education Department placed a series of roadside signs that mark the route Sybil Ludington took when she helped muster her father’s militia.

In 1961 sculptor Anna Hyatt Huntington created a statue of Sybil, depicting the ardent, active young woman on horseback, intent on her task. The original full-size statue is in Carmel, a town along her route, and a smaller replica stands in Danbury. Another smaller original of the statue is on display in the Daughters of the American Revolution Museum in Washington, DC.

For the celebration of the bicentennial of the United States, Sybil Ludington was depicted on a postage stamp issued by the US Postal Service in 1975 as one of the Contributors to the Cause stamps in the United States Bicentennial Series. It was an apt description. Sybil willingly and bravely did contribute to the cause.

General Tryon, leaving Danbury aflame, then began leading the retreat of his troops toward their ships. Suspecting correctly that the American troops would be positioned along the route he had taken to get to Danbury, Tryon, with the aid of local Tories, took an alternate route. Locals tried to impede his progress by destroying a bridge, and through other acts.

Gravestone of Sybil Ludington.

Photo by Val Riordan

The American generals split their forces, with Wooster sending Arnold and Silliman to Ridgefield while he headed north of that town and encountered Tryon and his troops while they were eating breakfast. The Battle of Ridgefield ensued. In the fighting, General Wooster was hit in the back by a musket ball and died. While the troops of Generals Silliman and Arnold, along with those of Colonel Ludington, pursued the British as they retreated, locals also pitched in by shooting troops while hiding behind bushes and trees. According to an article that appeared in the Connecticut Journal, “The enemy’s loss is judged to be more than double our numbers, and about twenty prisoners.”

Skirmishes continued until the British were aboard their ships. By then, Sybil was likely asleep in her bed after her long ride the night before. Sybil’s contribution was acknowledged in Colonel Henry Ludington: A Memoir: “There is no extravagance in comparing her ride with that of Paul Revere and its midnight message. Nor was her errand less efficient than his.”

After the war, Sybil lived with her parents until, at age 23, she married Edmond Ogden. Their only child, Henry, born in 1786, was only 13 when Edmond died of yellow fever. After his death, Sybil bought and operated a tavern in Catskill, New York, and when she sold it six years later for three times the purchase price, she bought Henry—by then an attorney—and his wife and child a home in Unadilla, New York. She lived there with them for the next 30 years, grandmother to their four sons and two daughters.

But Henry preceded his mother in death, and without means of support, Sybil applied for a government pension. Although Sybil proved beyond a doubt that she was the wife of a veteran of the Revolutionary War, her request was denied, and she died less than six months later. Sybil was buried next to her parents. Her gravestone reads: IN MEMORY OF SIBBELL LUDINGTON, WIFE OF EDMOND OGDEN.

Colonel Henry Ludington: A Memoir by Willis Fletcher Johnson (Self-published, printed by his grandchildren Lavinia Elizabeth Ludington and Charles Henry Ludington, 1907)

Glory, Passion, and Principle: The Story of Eight Remarkable Women at the Core of the American Revolution by Melissa Lukeman Bohrer (Simon and Schuster, 2003)

Contains a chapter on Sybil Ludington

“New York Patriot” by V. T. Dacquino

www.archives.nysed.gov/apt/magazine/archivesmag_spring07.pdf

Sybil Ludington: The Call to Arms by V. T. Dacquino (Purple Mountain Press, 2000)