Grace Waring Martin and Rachel Clay Martin were young and fearless. The sisters-in-law were the wives of two sons in the Martin family. While their husbands were away fighting with the militia, Grace and Rachel, too, became involved—not on a battlefield but on a road near the family home.

When she was only 14, Grace Waring married William Martin. Rachel Clay, the first cousin of Henry Clay (a lawyer who represented Kentucky in both the Senate and in the House of Representatives) married William’s brother, Barkley Martin. The husbands were two of the eight children of Elizabeth Marshall and Abram Martin. The parents had both grown up in Caroline County and after their marriage settled near the town of Ninety Six in South Carolina, an area on the boundary of the land settled by farmers and the land inhabited by the Cherokee nation. Most of the settlers, like the Martins, were pioneers from other states. It was in Ninety Six that Abram and Elizabeth raised their seven sons and one daughter, Letty.

When the war broke out and the local militia asked for volunteers, Elizabeth said to her sons, “Go boys, fight for your country! Fight till death, if you must, but never let your country be dishonored. Were I a man I would go with you.” All seven of her sons joined the fight.

The Martin family home where Grace and Rachel were living with Elizabeth while their husbands were fighting with the militia was located in a dangerous area. A war was being waged between the Whigs and the Tories. Neighbors on either side of the conflict not only disagreed but took action to ruin each other’s farms, steal each other’s animals, and more. One neighbor even tarred and feathered another because of a disagreement about the war.

With the men away, Grace, Rachel, and Elizabeth, pro-Revolution women, were fearful of attacks by local Tories. Elizabeth Martin had previously been the target of such an attack. Tories had visited her home and slashed open her feather beds, which were a luxury cherished by South Carolina settlers. When her sons came home, bringing with them a wounded Continental Army soldier, Elizabeth asked them to pursue and punish the Tories. The young men departed but left the wounded soldier with Elizabeth. When Tories heard of this and came to take the soldier, Elizabeth successfully hid him from them. And so it continued: Tory versus Whig; Whig versus Tory.

One night, though, it was Whig versus the British. Grace and Rachel Martin heard that a courier carrying papers to be delivered to British officers commanding forces in the area would be traveling on a road through the heavily forested area near their home. The courier’s escort would be two British officers.

Could Grace and Rachel prevent delivery of the papers? They decided to try.

Grace and Rachel surely knew that what they were planning was dangerous, but they had something at stake. The plans being carried by the courier might be related to activities in which their husbands were involved. The women knew as well that plans were constantly changing—depending on circumstances, weather, geography, available equipment or ammunition, or news of troop movements or locations. They also knew that messages were often carried by men or women on horseback.

One source, The Pioneer Mothers of America by Harry Clinton Green and Mary Wolcott Green, suggests a conversation that might have taken place between the sisters-in-law.

“Grace,” said Mrs. Rachel banteringly, “if you were a soldier’s wife, I’d dare you to join me in capturing that courier and his papers for General Greene.”

“Soldier’s wife,” said Mrs. Grace scornfully, “I dare do anything you can do.”

The plan quickly matured.

Grace and Rachel’s plan was to seize the papers and send them to Major Nathanael Greene, commander of the Continental Army in the Southern Campaign.

At Elizabeth’s house, Grace and Rachel rifled through clothing left by their husbands and dressed themselves to look like militiamen. “With rifles over their shoulders and pistols in their belts,” they exited the house.

It was dark. They quietly made their way to the side of the road they knew the men would travel on. They hid behind bushes and trees that edged the road and waited. For some time it was silent except for the ordinary sounds of the forested land at night.

Meanwhile, at the Martin home, their mother-in-law, Elizabeth, saw the courier and soldiers pass by her house.

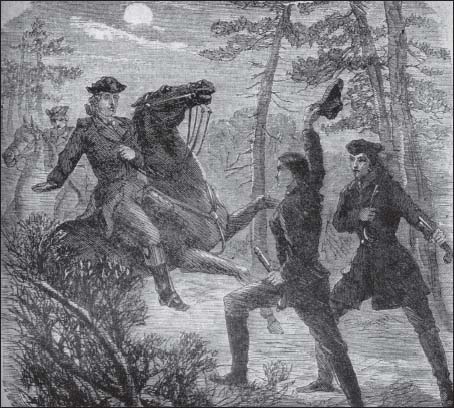

Grace and Rachel must soon have heard them as well. According to Elizabeth Ellet, author of Women of the American Revolution, who in the early 1800s interviewed ancestors and friends about the women who participated in the Revolution, “As they came close to the spot, the disguised women leaped from their covert in the bushes, presented their pistols at the officers, and demanded the instant surrender of the party and their despatches. The men were completely taken by surprise, and in their alarm at the sudden attack, yielded a prompt submission.”

Grace and Rachel Martin intercept courier.

Pioneer Mothers of America, 1912

Then Grace and Rachel demanded the men accept parole—an agreement by the men not to take up arms against the Americans or encourage others to do so in exchange for their release. The men signed a paper agreeing to the parole, then rode back in the direction they had come.

Grace and Rachel returned home via a shortcut through the woods, then changed from their husbands’ clothes into their own. A bit later, when Elizabeth heard a knock at the door, she opened it to see the courier and the two soldiers. Grace and Rachel might have been wondering if the soldiers had discovered that they’d been tricked.

Elizabeth greeted the men and recognized them as those she had seen ride by earlier. She asked, according to Ellet, why they were “returning so soon after they had passed. They replied by showing their paroles, saying they had been taken prisoners by two rebel lads.”

The conversation continued as the two young wives asked the men if they were armed and, if so, why they hadn’t used their weapons. The officers admitted to having been taken off guard and said that the confrontation had happened so quickly they didn’t have time to grab and use their guns.

Yet why had the men stopped? They wanted a place to stay for the night, they said. Satisfied with their explanation, Elizabeth let them in.

Did Grace and Rachel sleep well that night? We’ll never know. According to Ellet, the soldiers “departed the next morning, having no suspicion that they owed their capture to the very women whose hospitality they had claimed.” And Grace and Rachel found a messenger to carry the seized papers to General Greene, commander of the Continental Army in the South.

While some of Abram and Elizabeth’s sons were wounded in the war, six survived. Grace’s husband, William, was killed when he was aiming his cannon during the Siege of Augusta, after serving in the Sieges of Savannah and Charleston. Grace raised their two sons and a daughter on her own and never remarried. Rachel and Barkley Martin, who didn’t have children, were reunited at war’s end. Rachel lived into her 80s.

Grace and Rachel Martin are still remembered in South Carolina for their risky act.

“Grace and Rachel Martin”

A Woman’s Light: Making History in South Carolina

South Carolina State Museum

www.scmuseum.org/women/Martin.html

“The Martin Women of Edgefield 1851”

Women of South Carolina in the Revolution

http://sciway3.net/clark/revolutionarywar/womenofrevolution.html

Pioneer Mothers of America by Harry Clinton Green and Mary Clinton Green, Second Volume (G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1912)

Women of the American Revolution, Vol. 1 by Elizabeth F. Ellet, contains a chapter on Grace and Rachel Martin