Rebecca Motte had a regal presence and appearance and was a member of one of the wealthiest and most prominent families of Charleston, South Carolina, as well as the mistress of several large plantations in eastern South Carolina. That’s why at least one of seven dirty, scruffy prisoners was surprised when she engineered their escape, and why it’s equally surprising that she helped a militia carry out an attack on her own home.

While serving in the Continental Army in South Carolina, Daniel Green had been captured on May 12, 1780, and confined to a prison ship, where he worked as a boat hand and was able to leave the ship to retrieve fresh water and supplies on land. On one such mission in March 1781, only two guards oversaw Green and six other prisoners. When Green and the other prisoners realized they could overpower the guards, they did so and then ran. Eventually Daniel Green and the other men ended up at Rebecca Motte’s plantation.

Rebecca cautioned the fugitives to hide during the day and sent food to them on the sly, since they were in danger of being recaptured. Then she planned their escape to a safer area in conjunction with the departure of a young lady who had been visiting her.

The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution by Benson J. Lossing, 1860

That night one of her servants led the escapees to the river, where they were ferried across in canoes. Then the servant led them up to the waiting overseer’s house for food and drink. Beds and bedclothes were provided for them. The men slept near the fire and in the morning were told to take what provisions they would need for their trip. Daniel Green later wrote:

[To think] of one so accomplished showing so much kindness and attention to us, of late so unused to humane treatment! … we were ragged, dirty, rough-looking fellows; yet notwithstanding our forlorn condition, they treated us as equals, spoke to us kindly, and made us feel that we had not served our country in vain.

Elegant ladies had to be gutsy during the Revolution. Rebecca Motte was gutsy more than once.

Rebecca Brewton was born on June 28, 1738. Before the Revolution, her Charleston family was among the wealthiest in South Carolina. In her early 20s, Rebecca married Jacob Motte, a wealthy plantation owner who served in the provincial legislature. They were the parents of six children, though only three of them lived to be adults. The fathers of both Rebecca and Jacob were the principal merchant bankers of mid-century South Carolina. Rebecca’s older brother, Miles Brewton, owned several ships and numerous plantations, and he was elected to the second Provincial Congress, a position of prestige. But in 1775, while he and his entire family were on their way to Philadelphia by ship, they died when they were lost at sea.

After Miles’s death, Rebecca and her three daughters lived in Miles Brewton’s house, a brick townhouse in Charleston that is today a national historic landmark. When the British took over Charleston on May 12, 1780, officers seized the house and confined Rebecca and her family to a few rooms. It required control on her part to live side by side with officers of the occupying British Army. After her husband died of his illness in January 1780, she decided to move with her daughters and her nephew’s widow, Mary Weyman Brewton, to Mt. Joseph, one of the family’s plantations. They traveled there by horseback over forested hills, and by swamplands to the home, which overlooked the Congaree River.

Mrs. Motte’s home was fortified and turned into Fort Motte.

The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution by Benson J. Lossing, 1860

In May 1781 Rebecca was living in the house on that same South Carolina plantation when 65 British soldiers, under the command of Captain Donald McPherson, arrived and took over. Once again Rebecca found herself and her family limited to a few rooms of their own home.

The soldiers dug a trench around the house, constructed a wall to surround it, and turned it into what they called Fort Motte. From its position on top of a hill just above the Congaree River, the British could spot any boats bringing supplies along the river going to and from Charleston, the main city in South Carolina. If the British had control of the river and the flow of supplies, they could retain control of the area. Fort Motte was one of a strategically located string of forts throughout the state. Control of the forts meant control of South Carolina. That was the British goal.

Meanwhile, the local militia, bent on foiling British plans and on reclaiming South Carolina for the Revolution, had the same goal. Leading the effort was Francis Marion—nicknamed “the Swamp Fox” because he and his men avoided the enemy by hiding out in swamps, and Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, known for his ability to ride a horse. With their militia, Marion and Lee approached the Motte plantation with the intent of dislodging the British from the fort. And they had to be clever in their approach.

After Captain McPherson saw the militia arrive, he ordered Rebecca and her family out. As they were leaving, carrying what they could, to move to a simple wooden farmhouse on an opposite hill but still on the plantation, Mary Weyman Brewton hesitated and picked up a quiver of arrows that had belonged to Rebecca’s brother, ones he’d reputedly gotten from a military man involved in the East India trade. She mentioned to Rebecca that the arrows would be safer in her care. Later, those arrows would come in handy.

As the militia readied its attack on the fort, Henry Lee set up on the hill near the farmhouse where Rebecca and her family were staying. Francis Marion and his troops positioned themselves on another side. The ditch around the fort made it logistically difficult for his troops to get close enough to attack, yet they set up a six-pounder (a cannon) and began using it to pound the walls of the fort.

Inside Fort Motte, Captain McPherson and his troops weren’t faring too well either. They didn’t have any heavy artillery—cannons or other large guns—and were running out of ammunition. They needed backup.

It was almost there. Captain McPherson could see the campfires of the British Lord Rawdon and his troops, who were camped across the river on a hill. Marion, Lee, and Rebecca could see their campfires as well and realized that by the next day, Rawdon’s troops would join McPherson’s, and Marion and Lee wouldn’t be able to defeat them. They had to take action before Rawdon’s troops arrived. Rebecca likely watched Marion’s troops continue to fire at the walls of the fort, but the shots weren’t having a strong effect.

Rebecca listened as Marion and Lee plotted, then she interrupted, telling them that her house occupied almost all of Fort Motte. Her comment gave Lee and Marion an idea that they didn’t want to suggest. If they set fire to her house, the British would have to run out of it and surrender.

Yet it seemed too drastic a measure. It was the elegant Mrs. Motte’s home. She had been a gracious hostess and had also been nursing the sick and wounded that were in their company.

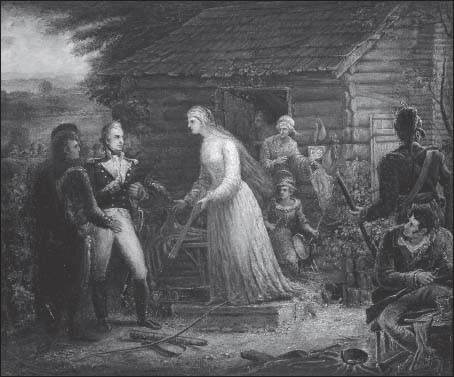

But when they told her their idea, she not only embraced it, but retrieved the arrows her cousin had taken from the house and presented them to Marion as the means of shooting fire at the house.

Rebecca Motte giving her arrows to Francis Marion.

United States Senate

The plan was accepted and put in place. In the morning Rebecca, her daughters, her niece, Marion, Lee, and their militia waited and watched as the sun rose and its rays beat down on the shingles of the roof of Rebecca’s house. The hotter the shingles were, the quicker they would catch fire. Lord Rawdon and his men had not yet arrived. By noon on May 12, 1781, Marion and his men crept close enough to the fort to shoot at it with an arrow.

Prior to implementing their plan, however, they gave Captain McPherson warning of their attack, a not-uncommon practice that gave the opposing side a chance to evaluate the situation and choose to fight or surrender. Lord Rawdon and his troops hadn’t arrived and wouldn’t before Marion and Lee’s plan was put into effect. A surrender would save lives. McPherson declined the offer.

The attack began. Some arrows were fired via rifles, but not all. Rebecca and the others watched as, according to an 1846 account, a

bow was put into the hands of Nathan Savage, a private in Marion’s brigade…. Balls of blazing rosin and brimstone were attached to the arrows, and … sent by the vigorous arm of the militia-man against the roof. They took effect, in three different quarters, and the shingles were soon in a blaze. McPherson immediately ordered a party to the roof, but this had been prepared for, and the fire of the six-pounder soon drove the soldiers down. The flames began to rage, the besiegers were on the alert, guarding every passage, and no longer hopeful of Rawdon, McPherson hung out the white flag imploring mercy.

After the surrender, the British soldiers joined the militiamen in putting out the fire—basically saving Rebecca’s home. It wasn’t just a kind gesture; they were likely afraid the flames would ignite the gunpowder stored in the house. Instead of being taken as prisoners, the British soldiers were paroled: they agreed they wouldn’t again fight against the Revolution.

What happened next might be hard to believe. Rebecca provided a lavish dinner for both the British and the American officers, using the social gathering to dampen the hostility of the afternoon’s events.

After the siege of Fort Motte and other conflicts that finally ended the war, Rebecca was saddled with the debts of her dead husband. Like many others, she had lost all of her property, with the exception of her slaves. Vowing to pay off her debts and regain her financial independence, she appealed to a friend to loan her the money to buy land on the Santee River on which she could grow rice. She had slave quarters and a simple home built for herself, and she concentrated on making the new plantation a success. By 1806 she was recovering financially and wrote to one of her children:

Now I have told you all the news I know of, I will inform you about my crop. I have a better prospect of a good crop than I have ever had; there were more pains taken in planting; all my seed-rice was hand-picked; and if rice should be a good price next year, I shall pay all my debts, I hope …

Your affectionate mother,

R. Motte

Rebecca continued to live at her plantation on the Santee River and was seen around the area, according to A Charleston Album by Margaret Hayne Harrison, wearing “a high crowned ruffled mobcap, a square white neck kerchief pinned down in front, tight elbow sleeves, black silk mittens on her hands and arms and a full skirt with a pocket, a silver chain from which hung a pincushion, scissors and keys.”

She died on January 10, 1815, at the age of 76.

A Charleston Album by Margaret Hayne Harrison

(R. R. Smith, 1953)

Available on Google Books

The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution by Benson J. Lossing (Harper Brothers, 1860)

“Mrs. Motte Directing Generals Marion and Lee to Burn Her Mansion to Dislodge the British”

United States Senate

www.senate.gov/artandhistory/art/artifact/Painting_33_00001.htm

Women of the American Revolution, Vol. II by Elizabeth F. Ellet, contains a chapter on Rebecca Motte.