It was over 100 degrees on June 28, 1778, at the Battle of Mon-mouth. Many men died of heatstroke. Many women were on the New Jersey battlefield that day as well, carrying water to thirsty soldiers, nursing the wounded, and sponging cannons with water to cool them. One woman was helping her husband as he operated a cannon when he was shot. What did she do?

Dr. Albigence Waldo, a surgeon, heard of her actions from an officer he treated. Five days later, the doctor wrote in his journal:

One of the camp women I must give a little praise to. Her gallant [husband], whom she attended in battle, being shot down, she immediately took up his gun and cartridges and like a Spartan heroine fought with astonishing bravery, discharging the piece with as much regularity as any soldier present. This a wounded officer, whom I dressed, told me he did see himself, she being in his platoon, and assured me I might depend on its truth.

A woman taking over a cannon would have been quite a sight to see. Perhaps, though, she wasn’t the only woman helping with a cannon that day.

Seventeen-year-old Continental Army private Joseph Plumb Martin wrote of what he saw that day, though his saucy description that was included in his diary wasn’t printed until 50 years later, in 1830:

A woman whose husband belonged to the artillery and who was then attached to a piece in the engagement, attended with her husband at the piece for the whole time.

While in the act of reaching a cartridge and having one of her feet as far before the other as she could step, a cannon shot from the enemy passed directly between her legs without doing any other damage than carrying away all the lower part of her petticoat.

Looking at it with apparent unconcern, she observed that it was lucky it did not pass a little higher, for in that case it might have carried away something else….

But who was she? Neither entry mentions her name. Were the men speaking of the same woman?

Ten years after the appearance of Martin’s diary account, George Washington Parke Custis, the grandson of Martha Washington and the step-grandson of George Washington, sketched and described his version of the scene that took place at the Battle of Monmouth:

While Captain Molly was serving some water for the refreshment of the men, her husband received a shot in the head, and fell lifeless under the wheels of the piece. The heroine threw down the pail of water, and crying to her dead consort, “Lie there my darling while I avenge ye,” grasped the ramrod, … sent home the charge, and called to the matrosses to prime and fire. It was done. Then entering the sponge into the smoking muzzle of the cannon, the heroine performed to admiration the duties of the most expert artillerymen, while loud shots from the soldiers rang along the line….

The next morning … Washington received her graciously, gave her a piece of gold and assured her that her services should not be forgotten. This remarkable and intrepid woman survived the Revolution, never for an instant laying aside the appellation she has so nobly won … the famed Captain Molly at the Battle of Monmouth.

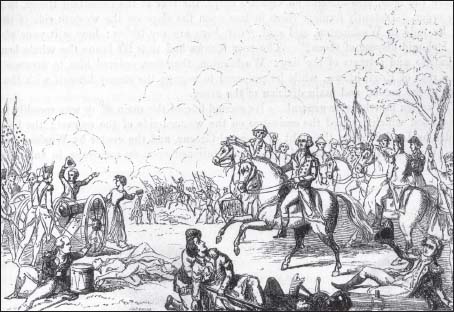

George Washington salutes Captain Molly on the field at Monmouth.

Drawing by George Washington Parke Custis, The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution by Benson J. Lossing, 1860

Custis gave her a name: Captain Molly. Custis’s story and sketch appeared in the National Intelligencer on February 22, 1840, and later in his book, Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington, in 1860. A friend of his, author-illustrator Benson Lossing, was taken with the tale, and with permission included Custis’s sketch and story in his book The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution in 1860. Molly’s fame spread. Yet who was she?

In 1848 artists Nathaniel Currier and his partner James Merritt Ives, also taken with the story, painted the scene, depicting her as strong and resolute. They called the painting The Heroine of Monmouth, Molly Pitcher, giving her another name. It stuck. Other artists drew her and called her that as well. They spread her fame.

Why Molly Pitcher? Many women on the battlefields of the American Revolution carried water to either cool the cannons or to quench the thirst of the soldiers. Did they carry the water in pails or pitchers? Pails make more sense. Yet one writer suggested how the name may have come about. “Thirsty, weary soldiers calling out, ‘Water! Over here, Molly! Bring that pitcher over here!’ And, finally, ‘Molly! Pitcher!’” That was one guess. Whether it evolved that way or another way, the name stuck.

Almost 30 years later, Currier & Ives again depicted “Molly Pitcher,” this time presenting a slimmer, more lithe Molly and describing her as “The wife of a Gunner in the American Army” who when her husband was killed took his place at the gun, and served throughout the battle.” Yet another artist, Edward Percy Moran, depicted a rather dressed-up Molly taking a more casual stance.

Library of Congress LC-USZC2-3186

Molly Pitcher’s image was also used in images to sell cartridges and many other items. She was celebrated on a 1928 US postage stamp. During World War II the Liberty ship SS Molly Pitcher was launched. A stretch of US Route 11 in Pennsylvania is known as the Molly Pitcher Highway.

Painting by Edward Percy Moran.

Library of Congress LC-USZC4-4969

Advertisement for the Union Metallic Cartridge Co. by artist Gilbert Gaul.

Library of Congress LC-USZC2-51103

However, Molly Pitcher is a name given to an image of a woman depicted by artists who represented the courage and fortitude of American women on the battlefield during the American Revolution, it is not the name of a real person. Molly Pitcher’s fame was spread by the many images of her painted by artists over the years.

Did anyone find out who the actual woman was who took over the cannon for her husband that day at Monmouth? People wanted to know. For years, many books claimed she was red-haired Mary Hays. What the various artists may or may not have known was that Mary Hays was described in her time as “homely in appearance with an eye defect; not refined in manner or language; of average height and heavy set … a great talker; smoked and chewed tobacco.”

That was not the image artists drew. It was probably an accurate description of her, though, and likely of some of the other women who traveled with their soldier husbands during the American Revolution. They were called camp followers, women who followed their husbands to war—some with children in tow—because they had no way of supporting themselves at home or were afraid of punishment by Tories, or of British soldiers who raided and ransacked many homes.

Mary Ludwig Hays may have been one of these camp followers. Like other camp followers, Mary may have helped carry water to men at the Battle of Monmouth, but historians now doubt whether she was even there. That’s just one of the questions about her. Historians are also not sure of the identity of her husband. She could have been married to William Hays or John Casper Hays, but according to several sources, when her husband—William or John—enlisted in the Continental Army, she went along with him. The sketchy and conflicting details available about her life reflect the lack of historical record of many ordinary men and women of the Revolutionary era whose lives were not set down in history books.

Many wives accompanied their husbands to war as did Mary Hays and Margaret Corbin. One such camp follower was 32-year-old Maria Cronkite. When her husband, a musician in the First New York Regiment, joined the army in 1777, she followed him, and during his enlistment she gave birth to several children and cared for them while she worked as a washerwoman for officers until the end of the war.

Camp followers helped out by washing clothes, as did Maria, or cooking, and sometimes they performed unpleasant tasks. At the Battle of Bemis Heights in upstate New York in October 1777, women made trips during the night to take clothes off of the dead and also to retrieve valuables or weapons.

One camp follower, Sarah Osborn, was married to Aaron Osborn, a blacksmith and Revolutionary War veteran in 1780. He didn’t tell her when he reenlisted, but he wanted her to go with him. At first she refused, but she agreed after his superior, Captain James Gregg, told her that “she should have the means of conveyance either in a wagon or on horseback.” That was important to her. According to orders from George Washington, the camp-following women were not to ride in the wagons but to walk behind the troops as they traveled. That winter Sarah instead rode in wagons and sleighs while many other women camp followers walked with the troops as they traveled hundreds of miles north and south. She earned her keep by washing and sewing for soldiers and on one occasion by baking bread.

While soldiers were busy building trenches and sheltering themselves from gunfire, Sarah brought beef, bread, and coffee to them. On one of these trips, she met General George Washington, who asked her if she “was not afraid of the cannonballs?” Her answer: “It would not do for the men to fight and starve too.”

There was yet another camp follower who was concerned about the men and personally about George Washington. Since the commander in chief of the Continental Army was away from his home for six years during the war, his wife and confidante, Martha, traveled by carriage to be with him at the army’s winter quarters when fighting was suspended. She was his secretary and acted as an intermediary between her husband and those seeking his assistance, boosted morale when she comforted sick or wounded soldiers, and hosted social events for officers and their wives, political leaders, and visiting foreign dignitaries.

After her husband died a few years after the war, Mary married George McCauley, becoming Mary McCauley. She worked at the ordinary job of cleaning and scrubbing buildings. More than 40 years after her actions on Monmouth, she was recognized by the Pennsylvania government for her service, not for her husband’s, and was granted a small pension but was not identified as Molly Pitcher during her life. During the 1876 centennial in Cumberland County—well after her death on January 22, 1832—an elaborate tombstone was installed in her honor that included both her name and that of Molly Pitcher.

Margaret Cochran Corbin is another candidate who may have served as the inspiration for Molly Pitcher. However, Margaret wasn’t at the Battle on Monmouth where the legend of Molly Pitcher began. When Margaret’s husband, John Corbin, enlisted in the First Company of the Pennsylvania Artillery as a matross, one who loaded and fired cannons, she accompanied him and traveled with the troops as a camp follower. Margaret and John were at the New York Battle of Fort Washington in November 1776. While tending the cannon, John was killed by a shot to the head. His commander gave the order to pull the cannon out of the way. One author imagined the scene:

Judge of his surprise when a wild-eyed and weeping young woman [Margaret], with hair flying, rushed up and besought him not to remove the gun…. “I know all about it,” she said. “Jack has shown me. Let me fire it.” He let her. And for several hours, she continued. Then, she was hit in the left shoulder. Others carried her away from the action.

The basic facts of this vivid story are true. John Corbin was killed and Margaret was wounded while manning a cannon, the scene so far depicted by artists.

Since Margaret Corbin was injured in the attack that killed her husband and was disabled by the shoulder wound, she appealed to the government for help and was the first woman to receive a pension from the United States. The resolution passed by the Continental Congress on July 6, 1779, reads:

Resolved—That Margaret Corbin, wounded and disabled at the attack on Fort Washington, while she heroically filled the post of her husband, who was killed by her side serving a piece of artillery, do receive during her natural life, or continuance of said disability, one half the monthly pay drawn by a soldier in service of these States; and that she now receive out of public stores, one suit of clothes, or value thereof in money.

One suit of clothes! She actually got a new suit each year. An 87-year-old man who lived near her remembered seeing her and called her “the famous Irishwoman called Captain Molly … she generally dressed in the petticoats of her sex, with an artilleryman’s coat over. Another local often saw her fishing in the Hudson River.”

Margaret had a rough life. Born in Pennsylvania on November 12, 1751, she was just five or six when her father was killed and her mother was taken captive during a Native American raid. She never saw her mother again, and was raised by her uncle until she married John Corbin when she was 16 years old. A soldier’s letter of September 15, 1785, from West Point, New York, site of an army fort, noted details of her later life: “I have procured a place for Capt. Molly till next spring, if she should live so long, about three miles from this place.”

Over the next four years she “was also furnished with old bed-sacks (originally filled with straw and used as soldiers’ mattresses), old sheets and even an old tent.” She “was saluted as ‘Captain Molly’ til death ended her miseries.”

When Margaret Corbin died around 1800, a cedar tree was planted at the head of her grave. In 1909 a monument to her was installed in her honor at Fort Tryon, New York, that was inscribed with the words: “MARGARET CORBIN—THE FIRST AMERICAN WOMAN TO TAKE A SOLDIER’S PART IN THE WAR FOR LIBERTY.” It was a tribute to her and not to the legendary Molly Pitcher.

Founding Myths: Stories That Hide Our Patriotic Past by Ray Raphael (The New Press, 2004)

“Sarah Osborn Recollects Her Experiences in the Revolutionary War, 1837”

History Matters

http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5833

“Molly Pitcher: True or False?”

New Jersey History Game 2001

New Jersey’s Monmouth County