The commanders and men who met at Gettysburg were as different as night and day. Not only were they from a mixture of rural and urban communities, but some were privileged, others farmers, woodsmen, hunters, and horsemen; still others were tradesmen or labourers who had never held a gun before.

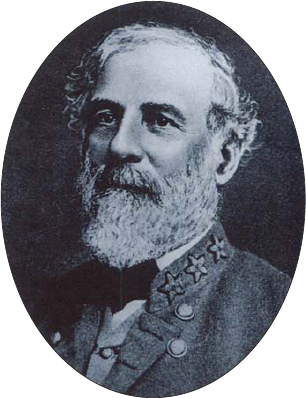

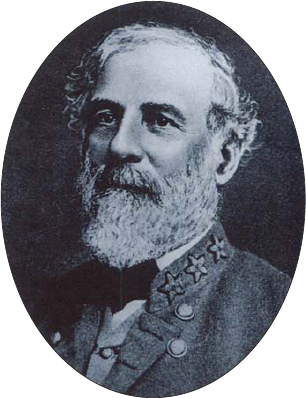

Robert E. Lee was the most respected commander in either army, having served in Mexico and at West Point, and having led the attack on Harper’s Ferry to capture John Brown. He turned down command of the Union Army to serve his home state of Virginia.

Lee was a career soldier, related to the oldest and best known families in the United States. An officer in the Mexican-American War, he had been superintendent of West Point and had led the marines which captured John Brown at Harper’s Ferry and had either taught or served with many of the men who wore blue or gray. Offered command of the United States Armed Forces, Lee deliberated and then turned the position down for one reason alone: he was a Virginian first and an American second. To him, his state of birth was his primary allegiance. His viewpoint was not unusual in the days of newspapers which were months old and telegraphs whose service was erratic at best, and all news was weighed against its local impact to ascertain its importance. Lee was not pro-slavery, and everyone who spoke of him referred to him as a gentleman in word and deed in the truest sense. He was educated, compassionate, intellectual and somewhat reserved, and he was highly thought of by all who came into contact with him – a man of principle and conviction. Choosing to serve Virginia instead of the United States was not an easy decision.

As a professional soldier, Lee was trained in the tactics of Napoleon, but the Mexican-American War and subsequent events had taught him several things about real war. He was bold and inventive, and had faith in his men. He took educated risks in forming battle plans, but was never foolhardy or reckless with the lives of the men he commanded; in fact, he was a man who listened to soldiers of all ranks and from all stations of life and considered their viewpoints and opinions. In return, his troops had faith in him which bordered almost on reverence. Next to Stonewall Jackson, he was the most aggressive commander the South had and respected by all. As a commander at West Point, he had helped train many younger officers on both sides.

Lee gave his subordinates room to exercise initiative. If he had a failing, perhaps it was this latitude he gave his commanders, since not all of them exercised the caution or boldness which he expected. Prior to Chancellorsville, the Army of Northern Virginia had been a perfectly balanced machine, with Jackson an aggressive and somewhat impetuous and inventive corps commander and Longstreet a more cautious and methodical one. Following Jackson’s death, Lee’s comfortable command structure was shattered. Lee’s command style was to issue overall orders or directives and then leave the exact manner of execution up to his subordinates. With Longstreet and Jackson everyone knew how one another thought and could reasonably guess how they would react, but with the introduction of Ewell and Hill as new corps commanders, uncertainty crept in the door.

Lee was not at his physical best at Gettysburg, as evidenced by his lack of ready plans and vacillation. His health was failing, and he was aware of this. Heart disease had already weakened him and a riding accident had damaged his hands earlier. However, part of his general lack of preparation must be attributed to Hill, who precipitated a battle which he had been told not to start without Lee’s express command. Lee had a plan which called for the Confederate Army to assemble at Cashtown with the mountains protecting its rear and make the Army of the Potomac move toward them. The illness of Hill and the brashness of Heth catapulted the Army of Northern Virginia into an engagement which Lee had expressly forbidden. However, the engagement escalated until he had no choice but to meet the enemy or fight a disastrous withdrawing action. That Lee made three attacks at different points on the Union lines on three different days has been cited as lack of a plan, but it is no sign of his failure as a commander, for Lee had no cavalry to tell him what he faced and so was testing the line to see if he could find a weak point. The intelligence he lacked would have informed him that Meade was shuttling Union troops back and forth to reinforce points in the line where they were needed.

George Gordon Meade was an organized commander who after his appointment as commander of the Army of the Potomac had two days to familiarize himself with his new command before engaging Lee at Gettysburg.

Aware of his frailty and the growing strength and competence of the Union forces, Lee felt time was running out for him and for his beloved Virginia. He acted boldly at Gettysburg because boldness would put the Union on the defensive and that would help the Southern cause. If Lee could have defeated the Union decisively at Gettysburg, he would have died a happy man, because such a Union defeat would have brought respite for Virginia or ended the war. As it was, there were two long years of warfare ahead. After the war, Lee became president of what is now Washington and Lee University and lived barely five years past Appomattox.

George Gordon Meade was a good general, perhaps much better than history allows. Like Lee, he was a career soldier and a devoted family man. Unlike Lee, he had a terrible sudden temper and sharp tongue when someone aroused his ire, and he did not hesitate to show it. However, he could be considerate and compassionate to his subordinates when the need arose. He too had served with many of the Confederate commanders and his subordinate Union commanders in earlier days, and he knew their strengths and weaknesses. Having recently been a corps commander, he was used to paying attention to detail and seeing that all the nuances of plans were carried out as assigned. If there was one major difference between Meade and Lee, this was it: when given the news that he had been appointed commander of the Army of the Potomac, Meade’s first response was that there were many others better suited to command – his second was to familiarize himself with every unit’s position, readiness and strength.

General Meade with his headquarters officers and Army of the Potomac corps and division commanders. Standing on the far right is a foreign military observer in uniform, distinguished by his shoulder sash and undress garrison cap.

Meade gave orders that were precise and well detailed, for he was a methodical and careful commander. As Gettysburg showed, he was quick to adapt to the changing necessities of combat where strategies were concerned, while many of his contemporaries were one-trick ponies. From the time he verbally accepted command of the Army of the Potomac, at 0300 hours on 28 June, 1863, until the clash at Gettysburg, he barely had 48 hours to assess the capabilities of his army, devise a battle plan, oversee logistics, and put his army into motion to find and stop the Army of Northern Virginia. Aware of Lincoln’s admonitions to find the Southerners and bring them into battle and destroy them, he gave that his full attention.

Few other commanders could have done what Meade did in not only preparing to meet the Confederate onslaught, but accepting command and improvising strategies while on the move. He freely used the strengths and talents of others around him, such as Reynolds, Howard, Doubleday, Slocum and Warren, to prepare the Union Army for its greatest test. That any should criticize him for lack of a speedy follow-up after the devastating battle at Gettysburg is typical of ‘armchair generals’, far removed from the scene of combat and the realities of the battlefield. There is the very real possibility that every Union soldier at Gettysburg was shell-shocked after the relentless three days of carnage. Very few men could do what Meade accomplished at Gettysburg, and one of those few happened to be in command of the other side.

When one considers J.E.B. Stuart, Alfred Pleasonton, Judson Kilpatrick, Wade Hampton, and George Armstrong Custer, one looks at cavalrymen who would have been at home as hussars in the armies of Napoleon or Wellington. They were personally fearless, tactically aggressive, and incapable of understanding the larger picture and strategy, sometimes to the point of recklessness. Although personable, these men were impulsive and vainglorious, as Stuart showed with his long ride that left the Army of Northern Virginia blind and without intelligence and as Custer showed throughout his career which culminated at Little Big Horn but could have done so at any juncture in his career had he been less lucky. To a man, they aggressively met battlefield situations head-on. Lee thought highly of Stuart, but he realized Stuart’s failings and knew that Stuart needed a firm hand to guide and give strategic direction.

Stuart was fond of uniforms, almost to the point of being a dandy. He loved banjo music and had a musician accompany him almost everywhere he campaigned. He was an excellent horseman, a dashing gentleman, and a devoted husband and father. He was one of the Confederacy’s most able commanders, and his death in 1864 left a void impossible to fill.

On the other side of the coin were cavalry commanders like John Buford and McIntosh. Buford was a proponent of what would be called ‘blitzkrieg’ nearly a century later. As far as he was concerned, infantry walked and cavalry rode to battle, but once there, they both fought on foot. Buford knew tactics and understood strategy, aware that cavalrymen armed with faster-firing breechloading carbines and Colt six-shot .44 revolvers could delay a superior enemy’s advance. With any number of other cavalry commanders at Gettysburg in that first meeting with Heth, a charge and blaze of glory would have stunned the Confederates, who would then have formed battle lines and blasted the riders into oblivion, and the net result would have been that Reynolds would have had to enter Gettysburg whistling Dixie if he was to enter at all.

Gettysburg highlights the best and the worst traits of commanders and the men they led. Without men of vision like Buford, Reynolds, Vincent, Chamberlain, Howard, Warren, and Meade, the North would have lost at Gettysburg. Without capable commanders like Lee, Longstreet, Hood, Pettigrew, Early, and Law, the Confederacy would have withered and faded after those three days of slaughter.

Reynolds’ death could have been a fatal blow to the Union if men such as Howard and Hancock had not been there to take command and keep unthinking commanders such as Sickles in line. Hancock had a knack for being in the right place at the right time, and he always managed to have a clean white shirt to wear with his uniform, no matter what the battlefield conditions or the distance from base. Hancock was a soldier’s soldier who knew not only what the right thing to do was, but when to do it, and how. Joshua Chamberlain was a college teacher of oratory. He put this to use when rallying his troops, preferring to sway them rather than bluntly order them, realizing that volunteers were different from career soldiers. His decisiveness and bold charge on Little Round Top may have been the action which saved the Union on 2 July.

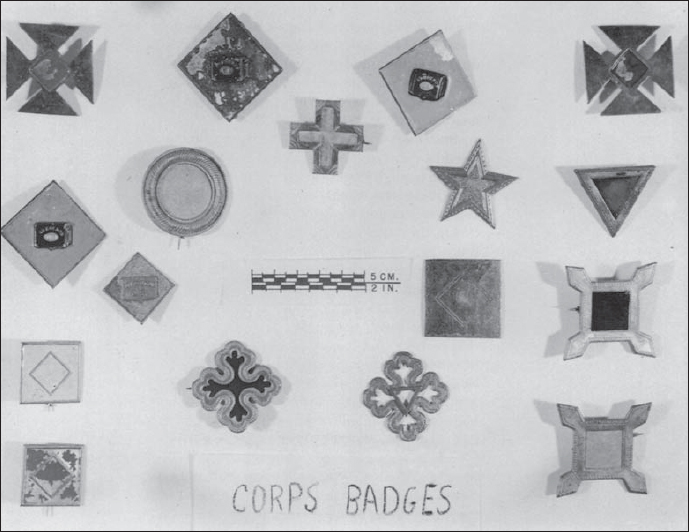

General Daniel Butterfield deserves credit not just for the rank and position he held (chief-of-staff), but for the practical changes he implemented. Today his name is obscured by many, but his actions affected every soldier in the army from Gettysburg to the present day. With Hooker he introduced standardized corps badges so soldiers from different corps and different divisions could be differentiated by the color of their badges. He is also credited with introducing a number of bugle calls during the civil war, among them Taps.

The Union Army adopted distinctive hat corps badges in 1863: I, circle; II, clover leaf; III, diamond; V, Maltese cross; VI, straight cross; XI, crescent; and XII, five-pointed star. 1st division emblem was always red; 2nd, white; and 3rd, blue.

James Longstreet was a favourite of Lee, called “Old Pete” or “Old Warhorse.” Lee depended upon him and trusted Longstreet’s judgement. He valued Longstreet’s opinion (even when it differed from his own) and listened to his counsel before making decisions. Longstreet was suffering the personal loss of three of his children, who had died of fever in Richmond in 1862. He was a calculating and cautious commander who believed in defensive warfare and thought no battle was better than one where the enemy dashed himself to bits against your prepared fortifications.

Richard (“Old Baldy”) Ewell was one of Jackson’s commanders and had earlier lost a leg. He had been Lee’s choice to command Jackson’s II corps. Although his leg wound had healed, he was hesitant at Gettysburg. Even though his troops were very successful on 1 July he was slow to follow up on an opportunity that could have won the day when it presented itself. When he finally decided to commit, Lee stopped him, knowing that the moment had passed, even if Ewell did not.

Jubal Early chewed tobacco, suffered from arthritis, and cursed freely, even in Lee’s presence. Lee referred to him as “My Bad Old Man,” but had confidence in this earthy, no-nonsense commander. Early passed through Gettysburg on his way to York and demanded ransom, but goods were hidden and little was given. He passed word back, and it eventually reached Hill and Heth. At Wrightsville Early’s troops helped locals put out the fire which threatened to burn down the town after the fleeing Union troops tried to burn the bridge they had failed to blow up. A.P. Hill was an erratic commander. When he felt well, he commanded well, but he was often ill. At Gettysburg he was sick, and many have speculated that his illness was psychosomatic. Robertson speculates Hill suffered from syphillis contracted in his West Point days.

Perhaps the most tragic figure at Gettysburg is George Pickett. Unfortunately his name has been sullied by association with the charge which he led that now bears his name. Yet Pickett was a capable commander. He was neither the brightest nor the most clever (having come at the bottom of his class at West Point), but he was a soldier who had a way with his men, and he followed orders. The charge across the fields of Gettysburg on 3 July, 1863, was primarily his unit. However, he had not chosen who was to charge: Longstreet had. Longstreet had not chosen to attack that point, Lee had, and Longstreet sent Pickett’s unit simply because it was fresh, and was most apt to succeed against the Union lines. How deeply Pickett felt about the charge was revealed in a meeting with Lee after the war, when he told a comrade that “that old man [Lee] cost him his division.”

As stated, A.P. Hill was ill at Gettysburg, and his lack of strict attention to Lee’s orders may have been in part due to his condition. The worst that can be said of Hill is that he was professional and somewhat unimaginative. Many have unfavourably compared Hill and Ewell to Jackson, but this is like comparing Napoleonic commanders to Wellington or Bonaparte, or armour commanders to Patton – there simply are not many who can do what these men did, so such comparisons fall short of the mark. Ewell was timid, and as yet uncertain how to manage a corps, and his performance at Gettysburg was less than many would have expected of him, especially his failure on the first day to follow up and seize the hills south of town. Instead he hesitated, and his hesitation gave the Union time to reorganize.

Reynolds was perhaps the best hope of what might have been. His brief spurt of glory allowed the Union to solidify a defence, and he died before he could make a mistake. Hancock, Howard, Warren, and Slocum showed inventiveness and an ability to work with others to achieve a goal; all had the respect of their men, which increased their effectiveness. After Reynolds, Hancock was perhaps the next most impressive commander, because his efforts on July 3rd helped turn the tide against the Confederacy.