Watching required patience. Roy had patience but probably not much time. Somewhere deep down, he was aware that things would catch up with him, so he was vigilant. He lay on the air mattress, chest against the rolled sleeping bag, arms propped on his elbows, the binoculars resting easily against his hands. This was day six of watching the Joshua Tree Athletic Club. So far, only the woman kept regular hours, on the road by 7:00 A.M., usually back by 5:45. Once, she hadn’t returned, probably doing the nasty with Francisco Flynn, the BLM cop.

The old farts were unpredictable, in and out, in and out, different times. Sometimes one or two of them would leave for a few hours, banging onto the highway in an ancient International pickup truck, back on the dirt parking lot before dark. But this morning, he’d hit pay dirt. He’d almost missed it, too. The truck pulled out at sunrise, carrying all three of them, just as he was setting up for the day. Three hours later and the woman’s Honda was still parked by her cabin, and it was close to 9:00 A.M.

Once, Roy had followed the woman up on Sage Flat and lost her. Had to hang back too far, but it was just a matter of patience. Couldn’t be very many people living up there in that rock garden.

He felt some respect for the cop. The cop had the way of the warrior, like in Castaneda’s book. Lived alone. Unpredictable. Kept his cool. That was what made him dangerous—he didn’t freeze up with fear the way most people did, just collapsing, hoping that begging

would keep them alive. Man, it was all he could do to hold back when they started all that whining. But dead guys couldn’t tell you much, and information was important. Knowing stuff was power. After he cut the first guy, Sorensen couldn’t wait to tell him all about the cop and the reporter, how they were an item. He thought he was buying time. He had that hopeful look on his face until just before he died.

Roy searched the grounds for signs of activity. No smoke rose from the wood-frame house behind the Joshua Tree Athletic Club, where the old guys lived, or from the stone chimney poking above the tin roof of the tavern. Time to take a closer look. He pulled the stopper from the air mattress, rolled it into a compact bundle, and tied it and the sleeping bag to the rack behind the dirt bike. He coasted down the back of the hill before starting the engine. No point in waking folks up, being inconsiderate. He hated it when people were rude and inconsiderate.

Roy cut along the dirt tracks that skirted the mining district. There’d been three towns during the heyday of the gold boom, all within a mile of each other, vying for top spot: Randsburg, Johannesburg, and Red Mountain. Randsburg and Johannesburg were respectable, had homes where the miners lived with their families. Red Mountain became the center of sin—dance halls, bars, and whorehouses. When the gold played out, Red Mountain and Randsburg had become ghost towns. Now Randsburg was being partially resuscitated by tourist dollars. Red Mountain had the Joshua Tree Athletic Club and fond memories of past times. Randsburg had TV. Roy pulled the motorcycle up behind the van, where he had left it near some dilapidated cabins sporting TV dishes.

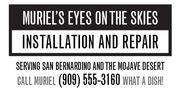

Roy’s latest choice of transportation, a television-repair van he’d picked up in San Bernardino, allowed him to hide in plain sight. Watching the tube and listening to the wind were the main events out here in Nowheresville, so the van functioned as a social ambulance, saving citizens from drinking too much and doing one another harm. The gray coveralls he wore bore the same name that was on the van:

He pushed the light dirt bike up the narrow ramp of the van and rested it against the sidewall on the left. Not having Jace and Hickey around made it easier for him to move around and talk to people, no clicking and head bobbing, no cackling and pot. Regular folks seemed almost comfortable around him. They commented on the catchy sign, and Roy made up stories about Muriel, what a smart lady she was, how much he liked working for her. Yeah, he liked the van and the way people reacted. Hell, maybe he’d take up TV repair after finishing up with old Francisco and Linda, the lady bartender with the shotgun.

But sometimes he got funny looks. His dyed hair lay against his scalp like dirty straw, light brown wisps peeking out from under his cap. A small matador’s knot tied off with a rubber band bobbed about at the back of his neck. The flat brown color lent his pale skin a chalky pallor that didn’t look quite right, a lifeless dead-guy look, and the dye job made the pink-rimmed eyes look like animated marbles. The wraparound shades helped a lot, hid the pink-rimmed paleness that made people look away. All in all, he was pleased with the effect. The disguise achieved the required metamorphosis from albino biker to Mr. Television Repairman. Besides, the world was full of weird people, and hey, this was California, land of half-breeds.

Linda sat at her iMac; she liked its simplicity and ease of use and the way it handled photos and text. Perfect for a reporter. Working at home, she could get twice as much done as she could at her desk at work. No Marston hanging around doing Bogey imitations, trying for Clark Kent to her Lois Lane, no Lucky Rogers, the eager-to-please sidekick, just uninterrupted quiet, especially with her dad and his buddies off on one of their expeditions. Of course, there was Hobbes wanting to go in or out, or staring at her in feline concentration

until she got up from the computer and put dry food in his dish. But now that she had the quiet time, the words wouldn’t come, at least not with any fluidity. Her copy was stilted, no flow.

She glanced out the window. The early-spring sky was bright blue, crisp with the cold. Bits of cloud raced shadows across the face of Red Mountain. Spring in the Mojave could be cold and blustery. She wondered why the television-repair van was in the parking lot next to the club. Her dad hadn’t said anything about the dish antenna not working or problems with reception. She shrugged, pushing it from her mind. She shifted her gaze back to the van. So why the TV repairman?

A tall figure in coveralls and cap came around from the driver’s side of the van, hand on his hat, the wind whipping at his clothing. He leaned against the gusts and disappeared behind the front of the club. Well, it was locked, and she wasn’t going to open it up. He’d find out for himself and go away. She returned to the computer screen, staring at the cursor blinking away where she had stopped typing. She closed her eyes, trying to concentrate on how to make earthquakes, magma activity, and the Richter scale intelligible and interesting to the Courier’s readership.

The Mammoth Lakes area was alive with volcanic activity. The eastern slope of the Sierras crawled with geologists, who poked their instruments into the ground, hopping around the country after each earthquake in perverse delight. She glanced back out the window, her eyes absently searching for the repairman. An unnamed anxiety began rising in her chest. Then it struck her with the force of a blow. It was him. Something about the way he moved. She looked out the window. Bits of wind-driven brush scooted along the ground. The cabin creaked in protest against the heavy gusts that pounded against it. She was suddenly aware of each wrenching sound, as if the walls would be ripped away and she would tumble endlessly across the desert floor.

She pushed the power switch on the computer, obliterating a couple hours of work, and eased herself away from the desk and window. The trapdoor to the tunnel was attached to the small utility table next to the stove, its hinges hidden against the outer legs and

under the linoleum flooring. It wasn’t invisible, but because people weren’t usually looking for a secret tunnel, it went unnoticed. Even if a person spied the thin lines of separation in the flooring, it was unlikely someone would think the table concealed a trapdoor, but it did. The connecting tunnel was a remnant from the days when the club was a center of sin. Ladies of the evening negotiated with their customers in San Bernardino County and led them into Kern County through the tunnels that connected the Joshua Tree Athletic Club to crib houses. Linda’s little cabin was a leftover from those days that had persisted into the fifties, defying prostitution ordinances in both jurisdictions.

Linda flipped a light switch next to the stove and lifted the table away from the wall, resting it on its side. Hobbes immediately ran to the opening, peering over the edge. She climbed partway into the opening, then picked up Hobbes with one hand. Grasping the handle on the bottom of the door, she pulled the table back into place and climbed to the bottom of steep wooden stairs. She squatted next to the ladder, her breaths coming in little gasps, pulling in the cool, musty odors under the house. Hobbes struggled under her arm, eager to be free to explore the forbidden tunnel. She held her breath, straining to hear. Above the pummeling of the wind, there was thumping, regular and rhythmic. Something was knocking at the door, not the wind. Had she locked the door? No, the cat had been in and out since early morning. It probably didn’t make any difference. The ancient lock was the original. The skeleton key hung from a cord next to the door frame.

She waited, unable to hear anything but the cabin groaning in the wind. Now and then, intermittent lulls brought a whispery quiet, as if the wind were gathering itself for a renewed assault. She heard footsteps at the front of the cabin, slow and deliberate. Hobbes struggled, mewing in protest at being held against his will. Linda placed him on the floor, and he immediately darted down the tunnel into the gloom. She stood next to the ladder, her head above a few inches below the floor. There it was again. Careful footsteps, over near her desk now. The cabin consisted of a single room with divided living spaces: a living room/bedroom combination near the

door, her desk in a corner, where it caught the light from two windows; the kitchen area—stove, refrigerator, and sink—occupying a corner toward the back; the toilet and tub tucked away in the opposite corner, behind a curtain that afforded a semblance of privacy from the rest of the room.

The footsteps came across the floor into the kitchen area, stopping next to the table almost directly above her. She covered her mouth and breathed into her hand. He couldn’t possibly hear breathing. He’d hear her heart pounding first. Hobbes came skittering back and rubbed on her ankles, then flopped on his back, begging for a tummy scratch. A plaintive meow would be next. Linda crouched down and softly rubbed the cat’s stomach. The steps moved nearer the stove and stopped. What was he doing? She backed away from the ladder and scurried along the narrow passageway. If she could get to the tavern and the shotgun and block the trapdoor, she’d be safe.

Her watch said 9:47. She knew she couldn’t have been down in the tunnel for more than five minutes. She was never, never going to be caught anywhere alone again, not until he was captured or dead. Why hadn’t someone stopped him by now? At the other end of the tunnel, she was more than a hundred feet from her cabin. Hobbes came racing out of the gloom. She was glad someone was having a good time. Bracing her feet against the wooden rungs of the homemade steps, she shoved up against the trapdoor. Something was blocking it. The door gave a fraction of an inch, just enough to reveal momentarily a crack of dim light; a heavy weight pressed it closed against her straining arms. She changed positions, placing her back against the bottom of the door and bracing her weight against the wall opposite the stairs. Linda shoved with her legs, using all of her strength. The door lifted a couple of inches. Her legs trembled with the effort; then the wooden step cracked and gave way, dumping her at the bottom of the entry, her leg scratched and bleeding. Someone, probably her dad, must have pushed the large cook’s table that occupied the center of the kitchen over against the wall to mop the floor and hadn’t put it back.

Linda took deep, centering breaths, fighting the panic. He wasn’t

going to find her. She waited, staring down the passageway. She wanted to be as far away as possible, but at this end of the tunnel, she didn’t know where he was. The tunnel was an earthen corridor shored and timbered every four or five feet. Her dad and the boys had nailed up a plywood ceiling and provided a one-by-twelve plank walkway. There probably wasn’t more than a couple of feet of earth separating the tunnel roof from the surface of the ground, but it was enough to dampen all sound. It was always cool. Quiet and musty with time. She had disappointed her dad and his pals because she never used it. She found being in the tunnel cramped and even a bit suffocating. She could sympathize with Frank’s claustrophobia as she started into the gloom. As she neared the cabin stairs, she was plunged into darkness. In a minute, the lights came on again, then flicked off and on several times. He’d discovered the light switch. She held her breath, her heart pounding so hard, she was afraid it would somehow give her away.

His footsteps moved around the room again, this time more rapidly, like he was doing a once-over. Then she heard the door close. Silence. She looked at her watch; it had been no more than a half hour from the time she’d first seen the repair van. She’d wait. Her dad and the boys had said they were headed over to Ridgecrest to the Lowe’s, a four- or five-hour expedition. She put her ear near one of the hinges on the door. Nothing except an occasional shudder from the wind.

She waited for another half an hour. She needed to pee. Returning to the steps, her head no more than a few inches from the floor, she heard the sounds of the wind buffeting the cabin, nothing more. She raised the table a couple of inches, trying to see out, but the door’s edge was against the wall, limiting her view to a small portion of the kitchen area. During a momentary lull, she listened intently; the stillness was complete. Her heart pounded in her chest as she pushed the table back and scrambled quickly to her feet. Everything was just as she’d left it. Feeling suddenly giddy with relief, she crossed back to her desk and looked out the window. The heaviness of dread lumped in her chest. The van was still there.

Then she heard the sound of plastic rings scraping on the iron

rod that supported the privacy curtain. “So there you are, Ms. Reyes. How ya doin’?” Roy pushed the curtain aside with one hand. In his other hand, he held a large automatic pistol. “Long time no see. Didn’t expect to see you come up from the floor. Now I know why the light switch doesn’t work. You’re full of surprises.” The pale forehead creased into a frown. “Say, where’s that big old double-barrel shotgun? Back under the counter at the bar, huh?” He nodded to himself. “Didn’t want to take any unnecessary chances, though. Better safe than sorry.” He slipped the gun inside his jacket and smiled. “Guess we can have that interview now. Get to know each other. I’m kind of an interesting guy once you get to know me.”

Someone was groaning. The sound vibrated in her ears and throat. Then she realized it was coming from her.

“Back among the living, are we? Had to whack you a couple a times to quiet you down.”

From where she lay trussed up on the floor, she could see the mountains sliding by the driver’s window of the van. They had to be heading north on 395. She slid forward as he hit the brakes and rolled against the wall on the turn.

“Ranger Frank lives somewhere up here along Sage Flat Road, right, Linda? Back on a first-name basis, if that’s okay with you.” He glanced back at her over his shoulder. “So where do I turn?”

“Find it yourself, Roy. Okay if I call you Roy?”

He shook his head. She felt the van slow and pull to a stop. Miller turned, removed his sunglasses, and slowly turned his head from side to side in disbelief. She recognized the pale face, but the lusterless brown hair gave him the appearance of an animated mannequin. He continued to move his head slowly back and forth, weary with the burden of inner truth.

“Linda, you think you can afford to be a smart-mouth without the shotgun? You think you still have the drop on ol’ Roy?” His pale eyes were flat and lightless. She looked away. He got out of the truck and opened the rear doors. “There you go. Nice bright day.” He stepped into the rear of the van and turned to close the doors. “On

the other hand, we don’t want to be distracted, especially you. You want to pay close attention, get in touch with reality.”

He stepped over her and slid out a seat from the workbench attached to a metal arm that locked it in place. “The thing for you to think about is how soon you’ll decide to cooperate. He pulled out a tool drawer and took out a pair of pruning shears. “See, if I have to do a little gardening, prune off a toe here, a finger there …” He let his voice trail off.

She tried to control the fear, but it enveloped her like a thick blanket.

His voice droned on. “Here a nip, there a nipple. So fucking noisy, all that screaming and hollering. Then after all that, the next thing you know, you’ll be begging me to draw a map to his place. And messy. Mess up my clean truck, my best coveralls. You like the logo?” He turned around, revealing the name Muriel’s Eyes on the Skies. “Pretty catchy, huh?” He drummed his fingers on the workbench. “For a reporter girl, you’re not too bright.” He reached down and rolled her over on her stomach. Grabbing one thumb, he twisted it up away from her hand. “Now here’s a twig that needs to come off.”

“It’s the dirt road next to the abandoned railroad tracks.” The voice she heard coming from herself sounded distant, as if she were only bearing witness to what was happening.