“I got a fine likeness of my sister at Whipple’s last-week…”

— Letter from Caroline Cushman to Henry Wyles Cushman (from the Cushman Collection in the New England Historic Genealogical Society)

1840

Frenchman Francois Gouraud holds public lectures and demonstrations of the daguerreotype in Boston, Massachusetts, and Providence, Rhode Island.

1850

Mathew Brady publishes his Gallery of Illustrious Americans, which contains portraits and biographies of eminent American citizens.

1859

John P. Soule establishes the Soule Art company and sells images of notable nineteenth century personages.

1861–1865

Itinerant photographers travel with military units during the Civil War, providing soldiers with pictures for loved ones at home.

1900

A quarter of a million Kodak Brownie Camera’s were sold for one dollar each.

1905–1920

Photographic postcards reach their peak popularity.

Identifying a photographer’s dates and places of operation is the most straightforward task involved in photo research. These two little pieces of information can help you place an ancestral portrait within a particular time period. When this data is pieced together with your genealogical research and other clues in the image, it may enable you to name the individual in the picture.

Collection of the Author

Photographer’s imprints contain a wide variety of information, from awards to telephone numbers.

A photographer’s imprint will allow you to trace the business dates for that photographer or studio. There are many different varieties of imprints, including handwritten tags, embossed labels, and rubber-stamped identifications. Photographers could order preprinted cards from a supplier or stamp or write the imprint on the card themselves.

Many of the images in your family collection will have a photographer’s imprint on the stock to which the image is mounted, and it’s important to know where to look for it.

Cased images can have the photographer’s name scratched into the plate or glass, or their name might appear on the brass mat or embossed into the velvet interior of the case. Photographers also used symbols or business cards to identify their work.

Variety of Information in an Imprint

With paper mounts, the photographer’s imprint may appear stamped, embossed, or handwritten on the mat. Card photographs can have imprints on either the front or back of the card. If a card photograph lacks an imprint, it may be a copy of an original card.

The imprint does not always refer to a photographer. It can be the name of a publisher or distributor. Many businesses sold card photographs published by companies other than the original photographer. The most popular were portraits of important individuals such as royalty and newsworthy events like the Civil War.

It’s more difficult to locate an imprint on prints or negatives than on cased images or cards. A photographer may have scratched his name into the emulsion on the negative, but that is an exception. Paper prints can contain an embossed imprint, but identification is usually stylistic rather than preprinted.

Generally an imprint identifies the name of the studio, publisher, or photographer. The simplest ones tell just the name of the photographer, usually an initial and a surname. More elaborate imprints can contain a list of services offered, awards received, and the photographer’s logo. In cases where only a surname appears, you will probably have difficulty researching that photographer. The same is true for imprints that only list the company name without the proprietor’s name. An address will enable you to place a photographer geographically and chronologically. A specific house and street number can narrow the search. An award or patent number will specify a date. Magazine articles about the award or patent will further support the information in the imprint. Each additional piece of information is another detail to be researched.

Where to Find Imprints on Images

Daguerreotypes, Ambrotypes, Tintypes: Name may be scratched into a plate or the emulsion, similar to an artist’s identification on a painting, or on the brass mat or velvet interior side of the case.

Paper Mounts: Handwritten, embossed, or stamped on the mat.

Card Photograph: On the front or back of the card.

Paper Prints: Not usually signed.

Negatives: Scratched into the emulsion.

Often, an imprint will mention a partnership or the prior owner of the studio. This will assist you in trying to locate the dates of operation. Partnerships were usually short-lived and photographers, unless they had a steady clientele and solid reputation, moved around looking for better economic opportunities.

Sometimes imprints contain misspellings or a deviation in the spelling of the photographer’s name. This can lead to difficulties in finding documentation. If you don’t find what you are looking for the first time, try searching for similar names, such as “Smyth,” if the name is spelled “Smith” in the imprint.

Types of Imprints

Once you have a name, there are several basic resources for locating photographers. Before you undertake painstaking research to locate information, try entering the name of the photographer in an online search engine, such as Google <google.com>. This search may lead you to a book, article, or online entry about the photo studio. Use both the general Web search engine as well as Google books <books.google.com>.

City or business directories, newspapers, almanacs, mug or booster books (biographical encyclopedias of important members of a community), photography magazines, and census records can all be used to locate photographers. None of these sources are complete, so consult a sampling before declaring an end to your search.

Directories appear in several formats: by locality, region, business, or house. Directories of a particular city or town appeared annually in larger cities and every few years in smaller towns. Regional or suburban listings usually included several small towns in their coverage area. Business directories contained information on the companies in the area. These are excellent sources for locating photographers. A typical listing will contain a person’s name, address, occupation, and often the name of his employer. When researching photographers, this data confirms the information in the imprint.

In cases where the imprint only includes the address and a business name, you can locate the name of the owner of the studio by using a house directory. Each listing is in order by street name, followed by house or building number and the names of the occupants.

National Photographic Publications

The Daguerreian Journal, 1850, continued as Humphrey’s Journal of Photography until 1870

The Philadelphia Photographer, 1864–1888

The Photographic Art Journal, 1851, bought out by American Journal of Photography (1852) in 1861

St. Louis Photographer (later the St. Louis and Canadian Photographer), 1883–1910

The St. Louis Practical Photographer, 1877–1882

Your public library or local historical society probably has directories for your city or town. If you are researching someone outside of your local area, it may require a little more effort to find the directories you’re looking for. The two largest collections of city directories are in the Library of Congress and the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts. Collections of digitized directories can be found on Ancestry.com <www.ancestry.com> and Fold3 <www.fold3.com>. Start your search by using an online search engine and the keywords city directory plus the name of the city or town.

Directories of regional photographers, in which you may find a full description of a photographer and his works, can save you a lot of time and effort. Photographers: A Sourcebook for Historical Research, 2d ed., edited by Peter Palmquist (Nevada City, Calif.: Carl Mautz Publishing, 2000) contains a worldwide bibliography of published lists of photographers by Richard Rudisill. You can also search online at Finding Photographers <www.findingphotographers.homestead.com>.

Sources

For information on photographers

To Find Photographers

Chris Steele and Ron Polito’s exhaustively researched A Directory of Massachusetts Photographers, 1839–1900 (Camden, Me.: Picton Press, 1993) relied on city directories to track photographers through time. Each citation for a photographer is in three parts: business listings, residential address, and advertisements. For example, using this book to research a photograph taken by Oscar T. Higgins reveals that he operated out of several addresses in Boston from 1853 to 1865 and had many different business partners.

1853: 92 Hanover St.

1854: 114 Hanover and 199 Hanover St.

1854: 94 Hanover St.

1855–1859: 114 Hanover

1864–1865: 109 Washington St.

Included in the information that Steele and Polito discovered in the directory listings were the following partnerships:

Welch & Higgins (1852–53)

Higgins & Pushee (1859–1860)

Higgins & Brothers (1860–61)

Higgins & Whitaker (1861)

Higgins & Collier (1862)

Higgins & Company (1863–65)

Higgins, Chandler & Company (ca. 1860–70)

If you were researching a photograph with the imprint Higgins & Whitaker, you would know the photograph was taken in 1861. Other information you collected from the image may support that conclusion. Newspapers often carried photographers’ advertisements, news items about them, and obituaries.

Advertisements in newspapers generally listed the services that a photographer offered and a price schedule. Unless the newspaper you are using is indexed, such material can be difficult to locate. This is a labor-intensive search and should be saved until you exhaust all other research options. Sometimes a newspaper would run a story on a local studio, especially if someone famous visited to have a portrait taken or a new process was introduced.

Occasionally, you will find a mention of a photographer in a newspaper in a completely unexpected spot. Photographer Samuel Masury trained with one of America’s first daguerreotypists, John Plumbe, whose skill with capturing images was well known. A reporter from a Providence, Rhode Island, newspaper heard that Masury opened a studio in the city and commented in an editorial on the images he took. “We have not seen any specimens of the art which we prefer to those of Mr. Masury.” The date of this article establishes Masury as a photographer operating in Providence in January 1846.

The United States Newspaper Project is a special federally funded project whose goal is to create a nationwide listing of newspapers published in each state. A central repository of newspapers in each state that is participating in the project can help you locate a newspaper for a particular area. In some localities, directories don’t exist but newspapers do. If you can find a newspaper for the town your photographer lived in, you may be able to obtain a microfilm reel through your local public library. The Library of Congress, Chronicling America <chroniclingamerica.loc.gov> is an online resource for newspapers from 1880–1922, and it also contains a list of U.S. newspapers published from 1690 to present day.

There are other digital newspaper collections, such as Ancestry.com <www.ancestry.com> and GenealogyBank.com <www.genealogybank.com>. For more useful sites see Everything You Need to Know About…How to Find Your Family History in Newspapers by Lisa Louise Cooke.

Subscription books, sometimes known as mug or booster books, can be a tremendous help in finding a photographer. These books featured biographies of prominent individuals. If the photographer you are researching was well established in a locality, he may have contributed to a county or town history. These mug book sketches, often written by the person depicted, contain biographical information that can help you. A note of warning: Since the subject of the sketch was often also its author, the importance of his life and work may be exaggerated. Back up any information from a subscription book with documented facts.

Publications created for a special purpose, such as a centennial celebration, are also good resources. Such publications usually accepted advertising from local businesses and might even feature a brief history of the studio in which you are interested

Photography magazines of the period also published articles on studios and accepted advertising. By searching an index of these journals for all years a studio was operating, you may find additional information on the photographer. From an article in the Photographic Art Journal, Steele and Polito learned that Luther Holman Hale began his photography business on Milk Street in Boston. This information does not appear in any other source.

Federal and state census records can also assist you in the search for the dates of a photographer. Census indexes are available on the Internet, in libraries, and through search services. Use the census indexes to supply a volume and page number for a photographer’s census report.

Don’t be misled when a photographer lists his occupation as something else, particularly in the early years of photography. Photographers often listed their occupation by the process in which they specialized. Many occupational titles were recorded for photographers, including daguerreotypist, ambrotypist, tintypist, and artist. Someone with multiple occupations would have had to pick one for the census taker, so don’t be thrown if you find the right guy with the wrong job.

Special censuses or nonpopulation schedules are helpful when available (see Special Census for Industry—1850, 1860, and 1870 sidebar). The Manufacturing or Industrial schedules from 1850 to 1880 include photographers. The purpose of these schedules was to compile information about manufacturing, mercantile, commercial, and trading businesses that had a gross product income of more than five hundred dollars.

Similar schedules taken in later years were destroyed. Information listed included the name of business or owner, amount of capital invested, and quantity and value of materials, labor, machinery, and products. Silas B. Brown, a Providence photographer, appeared in the 1860 census of industry. His product was ambrotypes; his occupation photographic artist; his worth fifteen hundred dollars, and he had five hundred picture frames and chemicals, cases, and other materials in his possession. The census also states that he had two male employees that cost him seventy-five dollars per month in wages.

Special Census for Industry—1850, 1860, and 1870

STATE: LOCATION OF ORIGINALS

Alabama: Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Ala.

California: California State Library, Sacramento, Calif.

Colorado (1870 only): Duke University Library, Durham, N.C.

Connecticut: Connecticut State Library, Hartford, Conn.

Delaware: Delaware Public Archives Commission, Dover, Del.

District of Columbia*: Duke University Library, Durham, N.C.

Florida*: Florida State University Library, Gainesville, Fla.

Idaho (1870 only): Idaho Historical Society, Boise, Idaho

Illinois*: Illinois State Archives, Springfield, Ill.

Indiana: Indiana State Library, Indianapolis, Ind.

Iowa*: State Historical Society of Iowa Library, Des Moines, Iowa

Kansas* (1860, 1870): Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka, Kans.

Kentucky*: Duke University Library, Durham, N.C.

Maine: Maine State Archives, Augusta, Maine

Maryland* (1850, 1860 Baltimore City, County only): Department of Legislative Reference, City Hall, Baltimore, Md.

Massachusetts*: Commonwealth of Massachusetts State Library and Archivist of the Commonwealth, Office of the Secretary of State (duplicates), Boston, Mass.

Michigan*: State Archives of Michigan, Lansing, Mich.

Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, Minn.

Mississippi: Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Miss.

Missouri: State Historical Society of Missouri, Columbia, Mo.

Montana* (1870): Montana Historical Society, Helena, Mont.

Nebraska* (1860, 1870): Nebraska State Historical Society, Lincoln, Nebr.

New Hampshire: New Hampshire State Library, Concord, N.H.

New Jersey: New Jersey State Library, Trenton, N.J.

New York: New York State Library, Albany, N.Y.

North Carolina: North Carolina Department of Archives and History, Raleigh, N.C.

Ohio: State Library of Ohio, Columbus, Ohio

Oregon: Oregon State Library Salem, Ore.

Pennsylvania*: NARA, Philadelphia, Pa. (Microfilm only)

Rhode Island: Rhode Island State Archives, Providence, R.I.

South Carolina: South Carolina Archives Department, Columbia, S.C.

Tennessee*: Duke University Library, Durham, N.C.

Texas*: Texas State Library, Austin, Tex.

Vermont*: Vermont State Library, Burlington, Vt.

Virginia*: Virginia State Library, Richmond, Va.

Washington* (1860, 1870): Washington State Library, Olympia, Wash.

West Virginia* (1870): West Virginia Department of Archives and History, Charleston, W.V.

Wisconsin: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison, Wis.

* Microfilm available through the National Archives regional facilities in addition to those listed. (Chart taken from “Nonpopulation Census Schedules: Their Location,” compiled by Claire Prechtel-Kluskens, 1995.)

While the majority of research on photographers is still accomplished using printed materials, there are also Internet resources to help with the process. One helpful Web advantage is that card catalogs for most major libraries are online, with the number increasing daily, so you can find books to aid your search without leaving the house.

The George Eastman House, an international museum of photography, has made its database of photographers available online through a telnet database <www.geh.org/gehdata.html>. Libraries and archives from all over the United States contributed information. The database has information on everyone from the small-town photographer to the world-renowned. Search terms for the database include photographer, geographic location, subject, and process. Specific information relating to business addresses is not available through the database, but it will help you place a photographer in a location within a time frame. City directories are also becoming available online through a variety of sites, such as Ancestry.com.

For individuals researching daguerreotypists, the premier resource for information on American photographers from 1839 to 1860 is John S. Craig’s Daguerreian Registry <www.craigcamera.com/dag> Craig spent decades compiling this data. Collectors, dealers, and other researchers have also submitted material for inclusion.

You can also locate information on photographers by typing the name into an online search engine, such as Google <www.google.com>. Consult online directories like those posted on <www.findingphotographers.homestead.com>. Use the listing by photographer on popular photo reunion site DeadFred.com <www.deadfred.com> to find other images by the same photographer and establish a time frame for the studio. Another option is to communicate with other researchers via message boards, such as U.K. Photographers at <www.rootsweb.ancestry.com>.

Researching photographers is challenging, but it can also be very rewarding. If you know the name of the photographer who took that mysterious image in your collection, the material you can locate on him will supply you with one more clue.

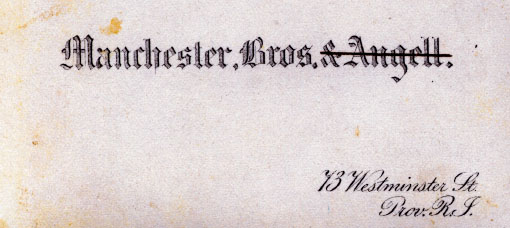

CASE STUDY: Tracking the Manchester Brothers

Collection of the Author

The Manchester Brothers of Providence, Rhode Island, used several different imprints during their years of business. The crossed out name represents the end of a partnership.

The search for the history of the Manchester Brothers photography imprint in Providence, Rhode Island, is an example of what research can uncover about a photographer. Following the guidelines in this chapter for identifying a photographer from an imprint and utilizing information in printed sources and online directed the research and helped piece together background information on the two brothers.

One of the first steps in researching a photographer is examining images taken by them. The imprints embossed on the images show that the company was known by several names: Manchester and Chapin, Manchester Brothers, Manchester Brothers and Angell, and Manchester Bros. No other information appears in the imprint except the names.

Two things are apparent from examining their images. First, the Manchester Brothers operated from the daguerreotype era to at least the end of the nineteenth century. Second, at least some of the images are of notable Rhode Islanders.

A search of the city directories for Providence, Rhode Island, revealed the following information:

1850–1853

Edwin H. and H.N. Manchester. Daguerrean Artist

33 Westminster St.

1853–1854

Manchesters and Chapin

19 & 33 Westminster St.

1853–1859

Manchesters and Chapin,

73 Westminster St.

1860–1862

Manchester and Brother

73 Westminster St.

1863

Manchester Brothers

73 Westminster St.

1864

Manchester Brothers

74 Westminster St.

1865

Manchester Brothers and Angell

73 Westminster St.

1866–1868

Manchester Brother & Angell

73 Westminster St.

1869–1878

Manchester Bros.

73 Westminster St.

1880

Manchester Bros.

329 Westminster St.

In addition to business addresses, the city directory listings provided the brothers’ names, Edwin and Henry N., their residential addresses, and Henry’s death on 24 November 1881. Directories are also useful in tracing the development of a family. In this case, George E. Manchester joined the family business in 1878. Cross-checking the listing revealed the names of the Manchesters’ partners: Joshua Chapin, a doctor, and Daniel Angell.

The next step is to take the information gleaned from the directories and look for obituaries in the local newspaper, The Providence Evening Bulletin. The death indexes confirm the death date on Henry N. and provide one for his brother Edwin, 20 March 1904. The obituary of Edwin includes a photograph of him, establishes him as a brother to Henry, and provides his middle initial—H. The brothers operated a daguerreotype studio in Newport, Rhode Island, in approximately 1842. At some point, Edwin opened a studio in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, and Henry started one in Providence. The George E. listed in the directories is mentioned as Henry’s son.

Since Edwin’s obituary states that the Manchesters were well known among the older families of Providence, the next step is to look at biographical encyclopedias. Henry Niles Manchester and Edwin Hartwell Manchester, as well as one of their partners, Joshua Chapin, are mentioned in a mug book. This biographical information establishes that they were in Providence in 1844 working with another photographer, Samuel Masury, in both Providence and Woonsocket, Rhode Island. The brothers also continued to operate a studio in Newport during the summer season.

The encyclopedia mentions that they were one of the first studios to introduce the paper print to Rhode Island, so they might be mentioned in William S. Johnson’s Nineteenth Century Photography: An Annotated Bibliography, 1839–1879 (Boston: G. K. Hall & Co., 1990). Johnson’s book indexes images by photographers that appeared in nineteenth-century periodicals. One image is listed for the Manchester Brothers and one for the Manchester Brothers and Angell. Both prints appeared in Harper’s Weekly and depict famous Rhode Islanders.

Census information on both Manchester brothers corroborated the information found in printed sources. A search of newspaper indexes at the Providence Public Library located a story about someone employed by the Manchesters and included a narrative about meeting and photographing Edgar Allan Poe.

Duplicating the printed source’s search using online databases illustrates the possibilities that exist for this type of research. From Craig’s Daguerreian Registry, it is learned that Edwin was a daguerreian in Providence, Rhode Island, from 1848 to 1860. A complete listing of business addresses and partnerships is part of his biography. However, the first new material for the Manchester Brothers is found in the citation for Henry Niles Manchester.

Henry was first listed as a daguerreian in 1843 at 75 Court Street, Boston, which was the address of Plumbe’s Gallery. In 1846, he was listed in Providence, R.I., at 13 Westminster Street, as Manchester, Thompson & Co. In 1847, he was listed alone at 33 Market Street. Another source has placed Manchester in business with Masury and Hartshorn in Boston.

The George Eastman House database, which provides a span of dates of operation for photographers and their location, did not yield any additional information. However, the Index to American Photographic Collections: Compiled at the International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House, 3d ed., edited by Andrew H. Eskin and Greg Drake (New York: G.K. Hall, 1996) tells you where to find other collections of Manchester Brothers photographs.

By taking this research and applying it to the images with the Manchester Brothers’ imprint, it is possible to approximate when a specific image was taken. A carte de visite with the imprint Manchester and Chapin would have been taken sometime between 1853 and 1859, while one with the imprint Manchester Brothers and Angell would have been taken between 1865 and 1868. Any further conclusions about the photographs will have to rely on the other methods of dating an image.

CASE STUDY: Which Is the Original?

Pat Strasser

Pat Strasser owns two identical images of the same man from two different photographers. She has two questions: Which one is the copy, and who is the man in the picture?

Photographic imprints supply part of the answer. The image on the left was taken by Orris Hunt, who states on his card that he was the successor to Harry Shepherd at 15 East Seventh St., St. Paul, Minnesota. It was quite common for one photographer to buy out another photographer’s studio when he decided to retire or move on. According to Biographies of Western Photographers by Carl Mautz (Brownsville, Calif.: Carl Mautz Publishing, 1997), Harry Shepherd bought out the People’s Photographic Gallery in 1887 and renamed it. He was a very successful African-American photographer in St. Paul, eventually owning three studios and winning an award for his work at the 1891 State Fair. He left the area around 1905, when presumably Orris Hunt purchased his East Seventh Street studio. This information suggests that the portrait of the unidentified young man was taken sometime after 1905.

The photo on the right is the copy. The photographer, Felix Schanz, was active in Fort Wayne, Indiana, in the 1920s, according to the George Eastman House database of photographers. In addition to taking new portraits of individuals, a basic part of a photographer’s business was making copies of existing images

If you are wondering about the connection between Fort Wayne and St. Paul, the answer is family. Pat Strasser’s father-in-law identified many of the pictures, with the exception of these two and a few others. The Strasser

family lived in Fort Wayne as early as 1867, when George Strasser was born. An older stepsister of George’s, Amada Hall (b. 1859), married a Danish immigrant, Edward Steade, in 1880. They moved to North Dakota and later Minneapolis, which is close to St. Paul. Pat thought this could be a portrait of Edward Steade, but given the dates of the photographer and other clues, this man is too young to be Edward. His clothing clues point to the early twentieth century: a loose-fitting jacket worn unbuttoned with a vest, knit tie, and shirt with a stand-up collar. It appears that he is wearing a false shirtfront with the tie tucked into it. Perhaps this was an attempt to dress up a more ordinary, everyday shirt. It is possible that this is a graduation picture. Given these clothing clues, the original photograph fits the time frame for Orris Hunt’s business and probably dates no later than 1910.

Here’s a theory as to what happened to that photograph. I suspect the man pictured is a son of Amada and Edward Steade. He had his picture taken by Orris Hunt and sent one to his grandparents. Years later, other family members wanted copies and visited Felix Schanz’s studio. Somehow, these two photographs (one original and one duplicate) ended up in her father-in-law’s collection. Pat Strasser is working on another lead for identification. There was another branch of the family living in Minneapolis that had a son at the right age for the portrait.