“To consider photography a mere mechanical art is a great mistake…photography to be successful requires expensive apparatus…”

— Coleman and Remington, Photographic Artists, 25 Westminster St., Providence (from the Rhode Island Historical Society)

1840s

The appearance of the first painted backdrop in a photograph.

1879

Thomas Edison produces the first incandescent light bulb; by 1930, most homes have electric lighting.

1900

There are 10,000 automobiles in the United States; by 1910 the number had grown to half a million, due to the more than 240 car manufacturers producing vehicles.

1925–1935

Zigzag patterns and vertical lines create dramatic effect on jazz-age, Art Deco buildings.

1960

The American Flag appears for the first time as it does today, with fifty stars.

While the type of photograph may place the image in a time period, the internal clues can narrow it down to a specific date. By carefully examining all the details present in a picture and recording them on a worksheet, you can discover the story of a photograph. In a portrait, facial characteristics can help you identify an image while the choice of props and backgrounds provide insight into the personality of the sitter.

Photographs of interior or exterior scenes contain many items that can help you date an image. For instance, to date an interior scene, you can research the decorative details. The presence or absence of certain technological details, such as light fixtures, trolley lines, and paved streets can date exterior shots. If a street scene has electric lights, for example, then you can research when lighting was installed in that part of town. Dating the style of architecture can also place the image in a time frame. The easiest detail to research in a street scene is signage. For some searches, it may be necessary to correspond with relatives or to contact experts on the subject to help you establish a date.

Details to Look For in an Image

Grant Emison

Use caution when comparing facial characteristics: a person’s face changes over time.

Probably the most difficult technique involved in photo identification is identifying and grouping people by facial characteristics. In some families, there may be a distinguishing characteristic, such as a mole that appears in a particular part of the face in several family members, or a distinctive shape of the eyes or nose. Hopefully your collection of photographs contains some identified images, so that you can begin to group them by family facial attributes.

Criminal investigators use facial characteristics to identify suspects, and you can use some of their techniques to try to identify people in family photographs. Police identification specialists use a standard list of characteristics to help create a composite. You will be attempting to do just that. Inspect the faces in your photographs and create a table of unique aspects to look for.

Trace a photocopy of a family portrait, reduce it to the scale of the photo you are trying to identify, and compare jaws, ears, and facial shape. This can also be done by scanning an image and manipulating it using photo-editing software. Be careful with this method of identification, though—a person’s face changes with age and weight tends to fluctuate.

Lay your identified family photos out in a timeline for each person. Compare your unidentified images to the timelines. Noticing similar noses, eyes, or cheekbones can establish a family connection. Those images that defy identification will require further research.

When you create your photographic timeline, use photocopies of the images so you can retain the layout of the collection as arranged by the original owner. Re-examining the photographs in the context in which they were given to you can also help to identify individuals.

Physical Characteristics to Examine

In particular, it is helpful to look at:

How Facial Recognition Software Works

Facial comparison is all about the details. Computer models that claim to accurately compare faces range from Google’s Picasa and Google Images to iPhoto for the Mac. So how does it work?

Basically, your face is composed of eighty various features that can be matched to another person or a photo of a person. In general this software looks for the distance between the eyes, the shape of the nose, cheekbones, and jaw line and whether or not a person has deep-set eyes.

The best results are achieved when both faces are looking directly into the camera. Obviously this doesn’t always happen with family photos, which often have individuals photographed at various angles in addition to image quality issues. It is possible to end up with photo matches for relatives or those individuals who just look like someone else.

On television, police investigation shows use facial recognition to catch criminals, but in real life, accuracy is not even close to 100 percent. A new program, called Faceoff, lets you compare two photos side by side. Learn more at <www.visualfacerecognition.com>.

Collection of the Author

Many photo studios used theatrical backdrops and props in their photographs. Note the hay in the foreground in this 1888 photo.

Studio photographers placed their customers in a deliberate setting using props and backdrops. Common props were toys, books, flowers, drapery, and columns. Their purpose was to add interest to the picture. People could also supply their own props, and in some cases, these can be significant. A woman posed in mourning clothes with a man’s photograph may be including her deceased husband in the portrait. Occupational portraits sometimes contain clues regarding the subject’s employment.

Painted backdrops first appeared in photographs in the 1840s, coinciding with the popularity of the daguerreotype. Backdrops provided the context for the props. Studios employed artists to create backdrops similar to the ones used in the theater. With the appropriate props, a visit to the photographer could transport customers into another world. Frontier scenes, landscapes, and architecture were popular backdrops in nineteenth-century images. Creative photographers would set props against an appropriate background painting. The backdrop could even substitute for actual props and make it appear that people were posing with items that are actually only painted surfaces, such as architectural details like balustrades. People could pose with bicycles in front of a landscape or appear to be riding in a car in an outdoor setting.

The choice of props and backdrops are not just useful for dating an image, but can provide clues to the character and personality of your ancestors. People could manipulate the setting of a photograph to create a sense of fantasy or comedy. They could have their photograph taken while miming an activity using materials they brought with them or ones the photographer had on hand. Young men in the late nineteenth century liked to be portrayed as fun-loving. Portraits often show them clowning for the camera.

CASE STUDY: Star Signs

Valerie Moran

Dating this photograph didn’t require examining clothing details or finding out when the photographer was in business. The evidence was so obvious that it was easy to overlook. Sometimes the smallest details immediately date a photograph—in this case, the details are the flags. By simply counting the number of stars, I discovered the picture was taken within a four-year time frame—4 July 1908, to 3 January 1912.

Twenty-seven versions of Old Glory have been used since the Stars and Stripes became official on 14 June 1777. Several versions of the American flag have flown since the advent of photography in 1839—so if you see one in a picture, count the stars and add up the rest of the clues to see if the date fits.

Valerie Moran thought the people in this picture were her ancestors, but she wasn’t sure. Once you have a time frame for a picture, see if other clues can narrow it down. Everyone in this photograph wears summer attire—most of the women have on lightweight, white summer dresses or shirts, while the men pose without jackets. The women’s attire—pouched-front blouses, wide belts, and long, straight skirts—fits the time period for the flags, as does the Gibson Girl hairstyle, in which the hair is pulled into a bun on top of the women’s heads. Just the combination of the women’s clothing and the date of the flag is enough to date this picture between 1908 and 1912.

But when identifying a photograph, I usually try to narrow the time frame even further. In this case, the history of the flag might date the picture to a day. Oklahoma joined the Union on 16 November 1907, but the new flag didn’t debut until 4 July 1908. The summer attire and new flag suggest that these people were celebrating a patriotic holiday, maybe the introduction of the new flag on Independence Day.

Based on her family data and continuing research, Moran suspects the photograph was taken in 1912. She believes the young man on the right is Clifford John Caminade (b. 1885), who would have been twenty-seven years old that year, and the older man on the left is his father, Louis Cass Caminade (b. 1852). Their ages, appearance, and date of the photo all support this conclusion.

Interior scenes should be as carefully examined as outdoor scenes. The artifacts in the picture may be family heirlooms or a new purchase. Family-owned luxury items, such as cameras, typewriters, binoculars, cars, and bicycles are clues to both the time period and the people pictured with them.

If you are unable to date an artifact by consulting reference books, an antique dealer can provide expertise or direct you to a collector who may be able to help. A curator at a local historical society or museum may also be a good resource.

The following should be consulted when trying to date an artifact:

Jane Schwerdtfeger

Architectural details and clothing clues can help date exterior photographs, c.1910.

Dating and identifying exterior scenes is not a subjective process; you will be able to date many of the visible details through library research. Use a magnifying glass to examine the image for particular items that can be dated, such as business signs and architectural and technological elements. Each one of these details can be researched further and provide irrefutable evidence of a time period.

Signage can be verified by consulting city directories. This will tell you when a company was in business and where it was located.

Architectural details can be researched by consulting photographs, books, and maps. You can compare your image to other street scenes of the same location. By consulting a reference book on architecture, you can establish when a particular style was popular. Maps often illustrate when a neighborhood was developed.

Technological elements can be the final clue to dating an image. For example, the condition of a street may be a clue. Many local histories mention when paving was introduced. They may also provide dates for the installation of gas and electric lights. The presence of telegraph lines, railroad tracks, fire hydrants, and bridges can also be dated.

Each step in the photo identification process—talking with relatives, researching the photographer, listing internal clues, dating costumes—requires a certain familiarity with library or online research. When identifying old photographs, you’ll use those techniques two basic ways—to research clues and access resources. Researching clues you find in images may mean looking at a book, talking with an expert, or searching online.

One of the best places to access resources is a library, either the brick and mortar variety or virtual ones online. Libraries, public and private, are great places to connect with resources—not just books but knowledgeable people and researchers. You may find yourself sleuthing for facts in an academic library, talking to a fellow researcher at a local historical society, using the special services offered by a public library, or hunting for answers online. Unless you live around the corner from a library like I do, you’ll also want to build a home library of frequently consulted books and maintain subscriptions to online databases.

Regardless of what you’re looking for, the local public library can be a very helpful first stop. The reference department, periodical department, and local history collection all have resources you’ll want to consult.

Reference librarians are trained to conduct interviews to help them identify what materials in their holdings can help answer a patron’s question. Getting a question answered is a matter of knowing how to ask one.

If you are looking for information outside of your local area, you may be directed to The American Library Association’s Directory of Libraries. It is primarily an index to libraries located in the United States, but it also includes material on Canada and Mexico. Each citation provides a brief description of the library, including departments, special services, and any special collections they maintain. This list includes private as well as public libraries. Another option is to search online for libraries in the area in which your ancestors lived.

Helpful Resources

The contents of reference departments vary from library to library, but you can count on even small libraries to have a good-quality encyclopedia and dictionary. These two tools enable you to learn more about an unfamiliar term found on the back of a picture.

Encyclopedias

The standard reference source is the multi-volume Encyclopaedia Britannica, because of the in-depth information it offers on specific topics. It has two indexes—macropedia and micropedia. You can search this set online at <www.britannica.com>.

Dictionaries

A good dictionary is a valuable resource. Everyone should either own one or have access to one online or through a library. The premier source of information on the English language is the Oxford English Dictionary, 2d ed., 20 vols. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), <www.oed.com>. This multi-volume wonder tells you the history of a word and how its meaning may have changed over time. It can be used to look up unfamiliar words and phrases encountered when researching photographs.

If you discover that a resource you need is located at another library, a librarian may be able to obtain it via interlibrary loan. Most public libraries and many academic libraries participate in this co-operative loaning arrangement. There is an occasional charge for interlibrary loan or conditions attached, such as the lending library may require that the material stay in your library.

Popular Magazines

Popular magazines from different time periods can be used for dating interior design trends. Some to look for:

While most public libraries have a local history collection, you may want to visit a special library. An archive or special collection usually refers to an institution or department that collects manuscripts, photographs, books, and other materials on a specific subject. Major genealogical libraries fall into the category of special libraries.

Archives and special libraries have strict rules for the use of their collections. For example, most archives require you to place personal materials, such as handbags and briefcases in lockers. Generally, you should only bring in the materials you actually need for the research you are currently undertaking. Pencils are required—no pens. You will also be asked for identification. They may even have you fill out a form asking about the resources that you have already consulted so they can suggest appropriate materials in their collection.

Some archives and special collections specialize in historic photographs. You can find a list of these institutions by consulting the American Library Association’s Directory of Libraries and the American Association of Museum’s Museum Directory.

Special Libraries

George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film

International Museum of Photography

Rochester, NY 14607

United States Army Military History-Institute

Attn: Special Collections

22 Ashburn Drive, Carlisle, PA 17013-5008

Steamship Historical Society of America, Baltimore

University of Baltimore Library

1420 Maryland Ave., Baltimore, MD 21201

Library of Congress

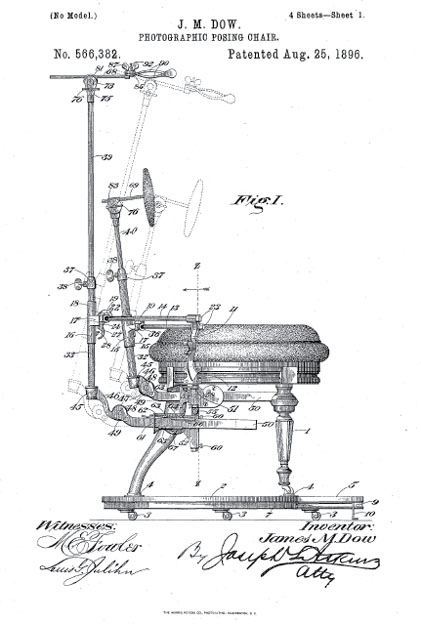

Improvement to the Photographic Posing-Chair Patent number: 566382. Filing date: Mar 14, 1895. Issue date: Aug 25, 1896. Invented by James Dow.

Another type of special library is a patent deposit facility. When inventors want assurance that their invention will be protected, they register it with the United States Patent Office. These patents are public information and are stored at deposit libraries across the country.

Many early photographers patented their improvements to photographic processes. If you’ve found a photographer’s advertisement that states they use a particular process, a patent search can help you date the image. Some photographers’ imprints include a patent number. Props could also be registered with the patent office. Because each patent contains a drawing of the invention, consulting the patent records may also help date the photograph.

Full patent records are available on Google <google.com>. On the homepage, select the drop down menu and then “Even More.” Click the Patent link to go to a search page for that collection. For instance, a search for photographic headrest results in a number of hits. See the photo of a patent in this chapter. You can narrow your search by defining it using the menu on the left hand side of the page.

References

Not all of your research will be done in a traditional library setting. Online searching is convenient, and with more material available online everyday, there’s no reason not to use these resources. Many academic institutions subscribe to databases, encyclopedias, and other basic reference tools that you can use from the comfort of your desk chair.

Use a general search engine like Google <google.com> or Bing <bing.com> to search for information on any detail present in your photographs, including the photographer’s name. Be as specific as possible to limit the number of hits. Many of the leading sites also have image search engines to help you hunt for family pictures.

A good research strategy is to consult the online card catalog of the largest library in your state or a nearby state to create a bibliography of print and online resources for the topic you’re researching. Then ask your local reference librarian to try to get relevant materials via interlibrary loan.

Local historical societies are slowly creating their own Web sites. While the content of these sites varies, they generally tell you how to contact the society, outline their collections, and post their hours. Some of the larger historical societies have guides for their collections as part of their site. Read their rules and regulations carefully, as not all accept queries to perform research.

You can also use your computer to communicate with others. E-mail enables you to correspond with collectors, organizations, and other family members. For instance, you may discover that a book you have been unable to obtain is available from an organization specializing in the topic.

Use online message boards to query other researchers to see if they might have your missing information. Find the appropriate message board for your topic with organizational sites such as Cyndi’s List <www.cyndislist.com> or by using those on Ancestry.com <ancestry.com>.

Bibliography

Care and Identification of 19th-Century Photographic Prints by James M. Reilly (Rochester, N.Y.: Eastman Kodak Co., 1986). If you have a question about the type of paper photograph you own, just look it up on the pull out chart that accompanies this book. The text can teach you about the technical aspects of the picture.

Collector’s Guide to Early Photographs, 2d ed. by O. Henry Mace (Iola, Wis.: Krause Publications, 1999). This slim volume can tell you just about everything you need to know about nineteenth-century photographs.

Dressed for the Photographer: Ordinary Americans and Fashion 1840–1900 by Joan L. Severa (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1995). This is a decade-by-decade look at American fashion in photographs. Each chapter begins with an overview of styles for men, women, and children, followed by analysis of individual images for costume details.

The Genealogist’s Address Book, 6th ed., by-Elizabeth Petty Bentley (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2009). This is a handy reference when I need to know if a local historical society has information on a particular photographer. It contains addresses for federal and state government resources and local historical resources, so I can easily find the repository or society who might have the information I need.

Unpuzzling Your Past: A Basic Guide to Genealogy by Emily Anne Croom (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2010). Basic, easy-to-understand information on tracing your family tree.

Victorian Costume for Ladies, 1860–1900 by Linda Setnik (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 2012). Setnik examines nineteenth-century fashion, breaking it down by topics ranging from sports attire to evening-wear. This book is intended for costume collectors, but you’ll find lots of interesting information on what women wore during those forty years.

If you have a large family photograph collection, you will want to build a home library that you can refer to as needed. Basic volumes should include a guide to photographic processes, a general history of photography, an overview of costume history, a genealogical research guide, and a printed family genealogy (if one exists). If your photograph collection has mostly one type of image, such as daguerreotypes, you might want to purchase books on that topic. Online book libraries, such as Google Books <books.google.com> and the Internet Archive <www.archive.org> make it easy to build a research library.

I keep the books in the bibliography sidebar on the shelf next to my desk for easy reference. I own a lot of books on specialized topics, but they’re used infrequently compared to the ones on this list. Keeping up with new publications means searching online book retailers, reading Library Journal (a weekly publication of the American Library Association), and making regular visits to bookstores (new and used). Since space is an issue at my house and probably yours, it’s important to buy only what you’ll actually use. The rest I borrow through my public library. The reference department is staffed by wonderful librarians who try to find the books and articles I need through interlibrary loan from libraries all over the country. Ask your reference staff about its interlibrary loan policies. This service can help you locate the resources you need to research that unidentified photograph.

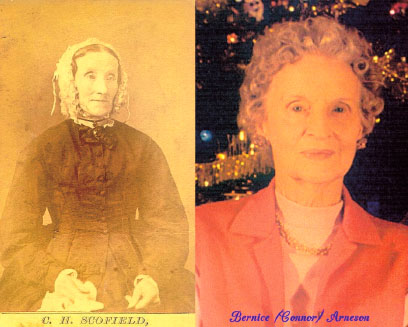

CASE STUDY: A Family Resemblance

Rita Werner

How do you identify a family photograph if you don’t even know what side of the family the image belongs to? The answer is to look for physical features that distinguish one side from the other. In Rita Werner’s case, the striking resemblance between two women in her photograph collection leaves no doubt to a family relationship. At age seventy-six, Grandmother Bernice (on the right) would look just like her unidentified ancestor (on the left) if she were wearing a daycap. With the family line identified, Rita wants to know who is in the first photograph and when it was taken.

The photographer’s imprint, C.H. Scofield of Utica, New York, is one clue. An online search reveals that a C.H. Scofield took stereoscopic pictures of Utica circa 1866 to 1900. You can view them on the Library of Congress American Memory Web site at <memory.loc.gov>. A photographer named C.H. Scofield (alternate spelling, Scholfield) also appears in Utica city directories from 1874 to at least 1889. He bragged in one city directory advertisement that he was the only photographer in Utica with rooms on the first floor. In the days before flash photography, natural light was an important component in taking portraits, so most studios were on the top floor. Due to having a studio accessible without climbing stairs, he probably attracted an older clientele—much like the woman on the left.

It is possible to narrow the time period of the photograph based on its physical characteristics. Yellow cards with rounded corners were popular for photographs between 1871 and 1874, according to William C. Darrah’s Cartes de Visite in Nineteenth Century Photography. The woman on the left is wearing a daycap with ruffles on the sides, an indication of her conservative approach to fashion. Women’s magazines of the nineteenth century suggested that only young women should dress fashionably because older, married women had other concerns—those of home and family. But no matter how old-fashioned a woman’s dress, attention to detail showed her awareness of current fashion. In this image, the woman wears a neck ribbon with a charm attached, as was the fashion in the 1870s. Her black dress, while simple in design, features some trim around the wrists and at the end of the jacket. The presence of the neck ribbon and the style of photograph suggest this image was taken in the early 1870s.

Werner suspects this woman is her fourth-great-grandmother, the grandmother of Thomas R. Connor (1848–1934). Connor was born in Ireland and immigrated to the United States in 1870. According to family legend, either Connor’s maternal or paternal grandmother raised him after his father, a merchant seaman, died at sea. It is possible that his grandmother immigrated with him, but this photograph might be the only evidence. A family photograph album does list a Mrs. E. Connor in the index. This mention could refer to the woman in the image and would support the family story. Werner also knows of an Elizabeth Connor (1814–1903) buried in a Utica cemetery, and she is trying to ascertain her origins.

Rita Werner may never be able to identify the woman in the left-hand photo, but one thing is certain—she is a relative. A quick glance at the two photographs she submitted leaves no doubt about it.

Relatives can be very helpful with facial identification. If any relatives from the unidentified subject’s generation are still living, you might want to enlist their help. They may recognize the individual in the photograph. Even if the name eludes them, they may be able to offer additional clues. The props and background in the image may aid your relatives in identifying the person in the photograph.

CASE STUDY: Celebrity Look-Alike

Library of Congress

Walt Whitman

Collection of the Author

Unidentified man

Walt Whitman is likely one of the most photographed men of the nineteenth century. In the mid-1850s, he posed for a portrait to include in his book The Leaves of Grass. Instead of wearing a suit, Whitman wore an open-necked work shirt and a hat and posed with his hand on one hip.

He continued to pose for portraits until shortly before his death. At a recent photo show, I spotted this cabinet card of an older man with a full beard and thought, doesn’t he look like Walt Whitman. Could it be him? Here’s how to compare faces.

Examine the features—eyes, nose, mouth and even hairline. This man looks a lot like Whitman with two exceptions—his eyebrows and the spacing between brow and eye. This man’s eyebrows are light and barely visible. Throughout his life, Whitman had strong brows even as a very elderly man.

When you think you own a previously unknown image of a famous person, take a few minutes to compare facial features and add up the photo facts. In most cases, it will just be a look-alike.

CASE STUDY: The Curiosity Shop

Providence Public Library

Burnett S.W. Bragunn Co’s Curiosity Shop, South Main Street, Providence c.1890

This unusual shop on the waterfront in Providence, Rhode Island, sold an eclectic mix of services and goods for mariners. Customers could buy secondhand clothing, boats, boat hardware, purchase railroad tickets for travel, or store their furniture “for fifty cents a week.”

You can tell much about the store simply by looking at its exterior:

Each one of the details in this photo, for instance, the pawnshop symbol and Jack the Ripper, can be researched using online search engines. Find more about the owner, Burnett S.W. Bragunn, in genealogical databases. The Curiosity Shop was demolished circa 1890.

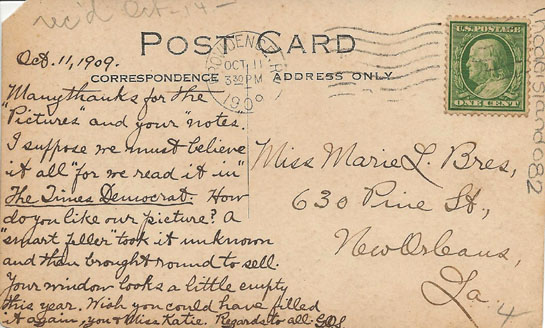

CASE STUDY: Examining the Front and the Back of an Image

Collection of the Author

Collection of the Author

Written on the front of this real photo postcard is “Maison Sackett. 37 Arlington Ave., Providence, R.I.” On the back is a larger story.

“October 11, 1909

Many thanks for the ‘Pictures’ and your ‘notes.’ I suppose we must believe it all ‘for we read it in’ The Times Democrat. How do you like our picture? A ‘smart feller’ took it unknown and then brought round to sell. Your window looks a little empty this year. Wish you could have filled it again, you & Miss Katie. Regards to all G.O.S.”

Let’s see how the details add up.

This research only begins to tell the story between the two families, but it’s a start. Every photo tells a tale. In this case, there are still questions to answer: Why did Marie and Katie spend the summer in Providence and how are the families acquainted?

The “smart feller” who took the image, was a roving photographer who traveled the neighborhood taking pictures of residences hoping to sell the views to the owners. In this case he was successful.

CASE STUDY: Internal Details

© Rhode Island Historical Society

In this street scene of Providence, Rhode Island, two elderly gentlemen rest on the doorstep of a building. A brief penciled caption on the reverse side of the image reads “Charles St.” There are a few business signs in the image that may help date it.

The internal details help narrow down the time period of the photo. The presence of trolley tracks, telephone lines, and cobblestone streets suggest that the photograph was taken after 1894. A history of the city of Providence verifies that telephone service was introduced in the city in 1881. The streets were laid with cobblestones between 1864 and 1880. Another clue to the time period are the electric trolley tracks, which were in existence from 1892 to 1994. In 1910, this particular type of trolley support pole was replaced.

A good next step is to research the four signs that appear in the photograph. The most easily read sign is for the Boston Dye House. City directory research for 1894–1910 does not reveal any dye houses of that name. The only other two businesses present in the image are a barbershop and a cigar store, but both are without names. Several possibilities are listed in the 1894–1910 business directories for Providence, Rhode Island.

The last sign is in Yiddish. It took consultation with several individuals before the sign was deciphered. The sign refers to a business that sells books and religious articles.

A final date for the photograph is derived from information in a house directory, which is arranged by street address and lists who lived or worked at any given address. This showed that for the period 1894–1910 only one dyer, an Israel Levy, lived on the right street. He was in business from 1895 to 1897. The only year both a cigar shop and a barbershop operated in close vicinity was 1896.