If you knew you had to give a speech in a week before 500 people, you would practice that speech until you could perform it with your eyes closed. If you knew you had a test the next day that would determine whether or not you passed a course, you would study the night before. If you knew you had to apply for a job, you would practice your interview skills, buy a nice outfit, and make sure your car had enough gas so you would have one less thing to worry about in the morning.

Why, then, would you not do what it takes to prepare for an emergency?

According to the Red Cross, “Emergencies can strike quickly and without warning. This may force you to evacuate your neighborhood or be confined to your home. What would you do if your basic services—water, gas, electricity, or communications—were shut off?” The vast majority of people are either not prepared at all or minimally prepared with a few extra bottles of water lying around the house. It’s simply not enough.

In this section, the focus is on what needs to be in place before any emergency occurs, including lists of items to have in your home, office, and car, prepping ideas for everyone in every situation, a plan for yourself and your family, and a breakdown of specifics for each type of disaster we talked about in Part One.

When we were kids, our parents and teachers told us that preparation is the key to success in school and in life. It may also save our lives.

Being prepared doesn’t demand a complete surrender to paranoia. Emergencies big and small will happen, and the more we are equipped to deal with them, the better we will do in responding and reacting. Not everyone will experience a mass shooting or an avalanche, but even smaller emergencies are addressed in this book, and in many cases the techniques, tips, and methods for a large event also apply to a home emergency such as a kitchen fire or a possible gas leak.

The first rule of preparedness is awareness of risk. Whatever part of the country or world you live in, there are specific natural and man-made circumstances that could lead to a major emergency or disaster in the future. Threats can be examined by categorizing them as global, national, regional, local, and individual.

•Global: nuclear war, asteroid impact, space weather event, supervolcanic eruption, war, climate change, pandemics

•National: weather events, terrorist acts, epidemics and pandemics

•Regional: weather events, flooding, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, epidemics

•Local: weather events, flooding, disease breakouts, mass shootings

Depending on where you live, the regional and local events you will be most concerned with will vary. People who live in hurricane zones must be more prepared for those events than people who live in desert regions, yet flash flooding can occur in both places. Terrorist acts can affect a local neighborhood or be on such a massive scale, like the September 11, 2001, attacks that they are considered global events.

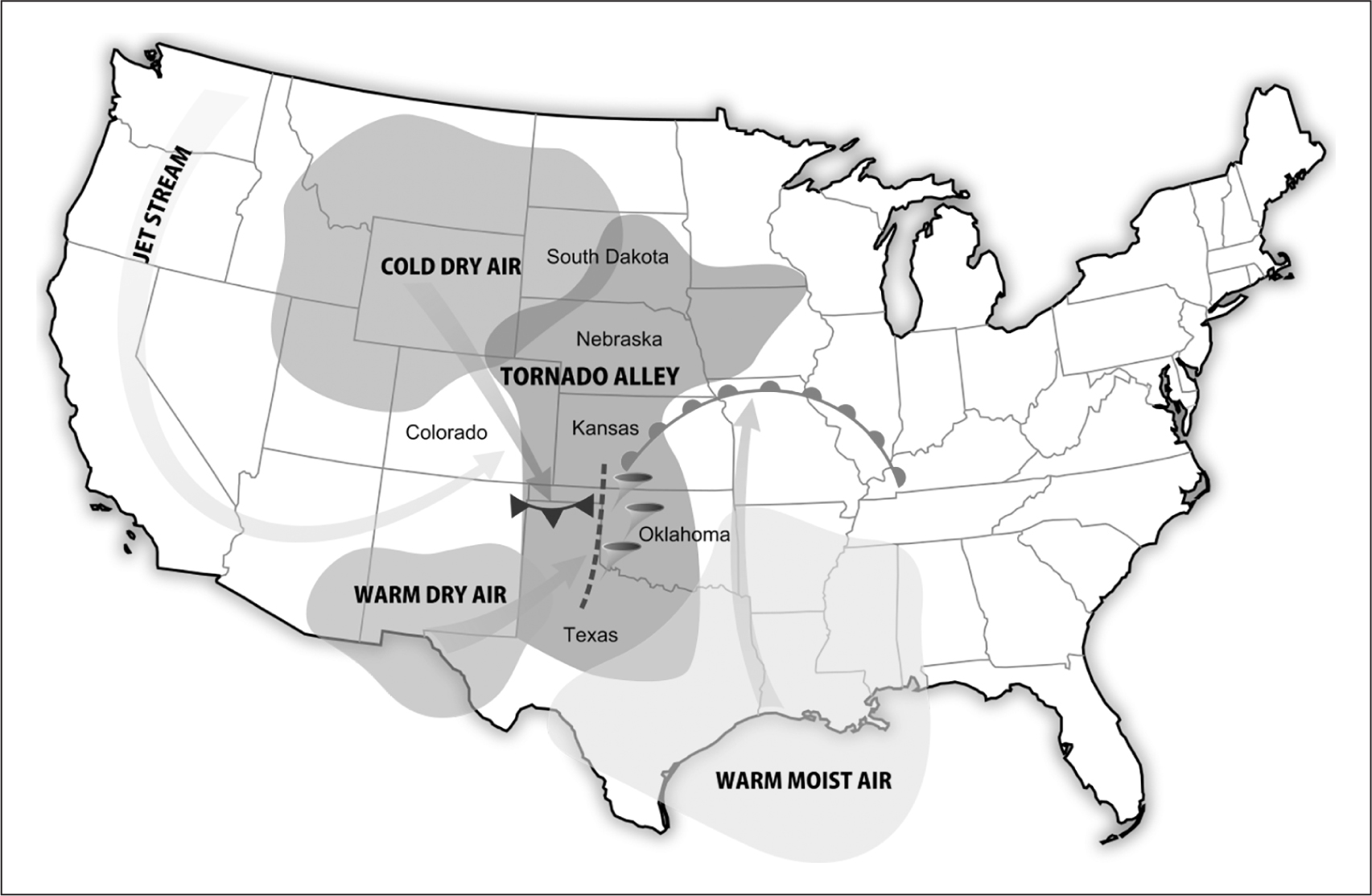

Part of being prepared for emergencies is being aware of your surroundings and the risk for certain disasters. For example, if you live in the region of the United States known as Tornado Alley, you should definitely make tornado preparedness a priority.

Obviously, the most imminent dangers occur with local and regional threats, and those should be addressed based on the dictates of the actual threats. It is more difficult to prepare for global events that may never happen, although we should at least take some precautions. Sometimes it’s easiest to start close to home.

DETERMINE THE THREATS

Do you live in Tornado Alley? Earthquake country? Near the coastline or in a large urban center? Identify your environment and then look at the threats that are most common. A solid disaster preparation plan will include even the remote possibilities, but much of your efforts will be in learning how to survive the ones with the highest rate of occurrence.

For example, if you live in a section of the country known for hurricanes, you must be ready to board up windows and evacuate when told to, especially if you live near the coast and storm surge is a possibility. Your plan will include a before, during, and after list of what to do in the event of a hurricane specifically. Maybe your neck of the woods also experiences major wildfires during dry spells. Your plan must also include ways to create defensible space around your home, cleaning up your garage of flammables and combustibles, and knowing your evacuation routes by heart. In both cases, you will need to know how to pack a bug-out bag or shelter in place if it’s too late to leave.

So, emergencies will carry with them specific ways of preparing and responding, yet many overlap, so that knowledge of surviving one carries over into another. It may seem overwhelming, but when broken down into small action steps, it can be done quickly and effectively.

SITUATION AWARENESS

Any emergency, big or small, requires a plan of action. That plan begins, though, long before the actual emergency takes place. It begins when the awareness that something can and will happen becomes reality. Just watch the news on television or on the Internet and it’s easy to see how we are all targets, even if what happens is confined to our own homes or neighborhoods.

The first step is to have access to knowledge, because knowledge is power. Knowing what is going on in your environment is critical to being ready for whatever might be coming your way, from a terrorist bombing to an active shooter, from a wall of wildfire to an oncoming tornado outbreak.

“Situational awareness” is the term given to the observation of one’s environment to determine potential threats and lines of defense. If you are not aware, you are not alert, and if you are not alert, you may be stuck in a situation that is difficult to extract yourself from. We have all heard of the “see something, say something” push by the government and law enforcement agencies to help identify potential terrorist attacks, shootings, and crimes in general. On a larger scale, being aware of what is normal in any given environment then allows us to have a baseline to work off of when we encounter something that feels or looks “off.”

In the summer 2017 issue of Emergency Management magazine, Andy Alitzer writes that the baseline we should be looking for is what is normal for our community, population, a particular event, or situation. For example, what is considered normal behavior at a high school football game, versus something out of the ordinary that catches the eye and causes concern. Or think of being at a crowded beach enjoying the sun and surf, then realizing that something is amiss because things don’t appear to be the norm for that particular situation. This is the kind of thing Alitzer says takes work and is different within each larger component of a community. Special events are harder still to get a baseline on, but a lot of this comes from experience, historical precedent, and often just gut instinct.

From that baseline, we then look for the possible situational issues that may arise to a disaster or emergency. A large music concert that includes fireworks has its own red flags, as does a parade of protestors in an organized march. Next, we need to look around us at the demeanor of people and notice anything out of the ordinary. Doing this may help us identify a threat such as a bombing or a shooting before it happens and possibly save our lives and the lives of others.

Man-made disasters such as auto accidents, bridge collapses, dam failures, and others require a different kind of awareness. We must know what is normal for our own environment. Walking across a bridge with ten thousand people may not be the wisest thing to do if the bridge is known to have suffered capacity load failure in the past. Driving in thick fog is a disaster waiting to happen that requires extra vigilance. Flying on a plane requires that we not only pay attention to the humans around us, but to various sounds, smells, and sights that may indicate a problem.

When it comes to natural disasters, we look around for changes in the wind, weather, smells, how we are feeling in the event of a toxic leak, the amount of water rushing down the local creek, or how high the waterline at the reservoir is. No matter what the potential emergency, being aware is the first line of defense. If we were hiking through the woods alone, we would be looking around for coyotes or wolves, mountain lions, other potentially dangerous critters like snakes, and even other potentially dangerous human beings. This same kind of vigilance, or at least a recognized awareness, is critical to being ready to respond and react.

The article “Situational Awareness: The First Line of Defense” for the March 27, 2017, Prepper’s Journal states that situational awareness is important on a daily basis. It is a tool that must be included in any survival or emergency plan. “There is a whole world of things going on around you, some good, some not so good. You want to be able to prepare when you see the not so good. It’s as close to a crystal ball as we can get.” This doesn’t mean you must walk around a paranoid mess, just that you must keep your eyes and ears open and trust your instincts when something, anything, in your surroundings does not fall into the usual baseline or the situational baseline that you are familiar with.

EMERGENCY ALERTS

This is a test. For the next sixty seconds, this station will conduct a test of the Emergency Broadcast System. This is only a test. If this had been an actual emergency, you would have been instructed where to tune in your area for news and official information. This concludes the test of the Emergency Broadcast System.

From 1963 to 1997, American households heard the above, or some version of it, broadcast over their televisions and radios on a regular basis. The Emergency Broadcast System was the warning system formerly used to alert citizens to a local, statewide, or national emergency situation. It was designed mainly to provide the president with a means of communicating to the public during an emergency. Between 1976 and 1996, the system was utilized to broadcast alerts for over 20,000 situations, although none of them involved a national emergency.

In 1997, the Emergency Broadcast System was replaced with the Emergency Alert System (EAS) we have today. The purpose stayed the same, and monthly and weekly tests continue to be broadcast on television and radio as well as over satellite digital audio service and direct broadcast satellite providers, cable television systems, and wireless cable systems. The EAS is designed to give the president of the United States the chance to address the nation within ten minutes of a major emergency. The new EAS has also been used in Amber Alerts of missing children as well as severe weather warnings, courtesy of National Weather Service alerts on a local and regional basis.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), governs the EAS along with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the National Weather Service (a part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Adminis tration [NOAA]) and has a number of prewritten scripts with information that would be used in a major emergency. Among the instructions in the scripts are suggestions that citizens not use phones and keep lines free, something that is a must even today with cell phones, as well as asking citizens to listen for further alerts, which might give out evacuation or shelter-in-place orders. Once official information began flowing, the system would be used for a message from the president or the next in line of command, were the president not available, as well as statewide and local emergency information.

The logo of the Emergency Alert System. The EAS replaced the Emergency Broadcast System in 1997.

Emergency alert tests are used to test the system at all levels so the FCC can be assured that, if needed, the system will work to disseminate proper information. It also helps the FCC identify stations that are cooperative with the system’s testing schedule and those that are not. Today, weekly tests are the norm, although during potential emergencies such as severe weather, they may occur more frequently.

When a national emergency does occur, it is up to the president to activate the EAS system, and FEMA has the authority to begin the alerts.

Another mass warning system is the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System (IPAWS), which is a modernized integration of the nation’s alert/ warning infrastructure that combines information from federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial alerting authorities and provides the public with updated information they need during an emergency. IPAWS uses the EAS as well as Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEAs), and also broadcasts over NOAA’s Weather Radio service, among others, all on a single interface. The more information that each system can contribute, the more information the public has to make the best choices during a major situation.

WEAs are a wonderful new tool for warning the public. They can be sent out at the state and local level, by the National Weather Service, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (Amber Alerts), and the president. These alerts come over cell phones like a text message but are accompanied by a sound or vibration to alert the user. These sounds are repeated twice. Texts are brief, including the type of emergency, the time, and any action that needs to be taken as well as the agency that is issuing the alert.

The Wireless Emergency Alert system allows government agencies such as NOAA or the police to send alerts to wireless devices such as your iPhone.

WEAs are not charged to cell phone users the way normal texts are, and they will come through even when a call or other use of the cell phone is in progress. Citizens must contact their cell phone service provider to get hooked up to the WEA system, but since nowadays most of us pay far more attention to our cell phones than to standard televisions and radios, it is critical to staying alert and up on the latest developments. This is even more important when away from home or when the power is out.

False Alarm!

It’s a typical Saturday morning, around 9:33 Eastern Time, on February 20, 1971. Radio station WOWO out of Fort Wayne, Indiana, is playing a popular Partridge Family song when suddenly the broadcast is interrupted by a series of loud beeps, followed by an official message ceasing all broadcasting immediately for an Emergency Action Notification directed by the president. What followed on that tense morning was the first actual national emergency broadcast over the Emergency Broadcast System.

The broadcaster, Bob Sievers, sounded terrified, and rightfully so, as he went on and on for at least half an hour broadcasting a vague national emergency that he had no details of. At 10:13 a.m. Eastern Time, another message finally came through saying, “Cancel message sent at 09:33 EST, repeat cancel message,” followed by a message authenticator. Turns out, the whole thing was a false alarm, a mistake caused by an accidental message sent out from the Department of Defense’s base at Cheyenne Mountain in Colorado to EBS-participating stations. The teletype operator there, W. S. Eberhardt, broadcast the wrong message with an authenticator code “Hatefulness” through the entire EBS system. The message and the code ordered the broadcasters to cease whatever they were playing and announce the emergency. Shortly afterwards, around 9:59 am, a correction message was sent out, but that one contained the wrong authenticator code and didn’t work! Finally at 10:13 a.m. the right cancellation message with the right code word “Impish” went out, ending the alert.

Many of the stations ignored the message, others jumped on it, as did WOWO, thinking it the real deal. But it was supposed to be only a message ordering a test, not a disaster of national proportions. President Richard Nixon never made his emergency message, the listeners and the broadcasters realized it was a mistake, and all returned to normal.

But for over a half an hour that morning, people thought the world might possibly be coming to an end. That fiasco taught the Federal Communications Commission a lot about how to fine-tune the EBS, which would later become the EAS we now have. Now we don’t worry as much about mistakenly sent messages as about hackers who can break into the system to announce an alien invasion or zombie attack. The actual broadcast is available on YouTube and other sites. Simply search “WOWO false alarm of 1971.”

More recently, on January 13, 2018, Hawaiians got the fright of their lives when an emergency broadcast told them to take shelter because a nuclear missile was heading their way. Given the tensions at the time between the United States and North Korea, which had been testing nuclear bombs and boasting they could now reach U.S. territory, one can understand why island residents were terrified. It turned out, however, that an employee at the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency somehow misunderstood that they were simply having a drill and instead triggered the real alarm. The employee was later fired, but an investigation led to the conclusion that insufficient protocols and safeguards, including computer software that didn’t clearly distinguish between exercises and the real thing, were in place to prevent human error.

In addition to these alert systems, which can be installed on your phone with a quick visit to your state and local emergency services websites (or FEMA), apps are available that can also serve as alert and information tools for heavy cell phone users. It’s as easy as visiting your provider’s app store, and since most of them are free, all you need to do is install them on your phone.

The Emergency Alert System and all the additional forms of alerts are the first communication you will get of a disaster or emergency. While social networking spreads information like wildfire, it isn’t always accurate. The EAS and other official warning systems will give the most updated information possible to help you know exactly what is happening, how it affects you, and what you need to do about it.

This is only a test. But one day, it could be the real thing.