Notes

1 Alan Greenspan, The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World (New York: Penguin Press, 2007), p. 95.

EPIGRAPH

Fernand Braudel, A History of Civilizations, translated by Richard Mayne (New York: The Penguin Press, 1994), p. 17.

Chapter 1: DISPARITIES AND PREREQUISITES

1 A sharp reduction in the probability of success, when there are multiple factors required in a given endeavor, even when the prerequisites are few and common, is just one of the things making equality of outcomes less likely. Other factors may be influences without being prerequisites, and yet the increased multiplicity of factors—both prerequisites and other influences—increases the number of possible combinations and permutations affecting outcomes, thereby reducing the likelihood of equality of successful outcomes. A concrete example of an influence that is not a prerequisite is that being left-handed is an advantage for a baseball player who is playing first base. Even though there have been a number of right-handed first basemen who have been excellent fielders, nevertheless left-handers have tended to be over-represented among first basemen.

2 The chances of having one, two, three, four or five of the prerequisites may be normally distributed, as in a bell curve, but the outcomes will not be. If the distribution of outcomes is plotted on a graph, with the number of prerequisites measured on the horizontal axis and successful outcomes measured on the vertical axis, all those people with one, two, three and four of the prerequisites will have zero successes, represented by a line that coincides with the horizontal axis. At five prerequisites, this line will rise at right angles to the horizontal axis, representing various degrees of success. This is clearly nothing like a bell curve.

3 World Illiteracy At Mid-Century: A Statistical Study (Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 1957), p. 15.

4 As of 1940, just under half of the women in the Terman group were employed full time. Lewis M. Terman, et al., The Gifted Child Grows Up: Twenty-Five Years’ Follow-Up of a Superior Group (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1947), p. 177.

5 Malcolm Gladwell, Outliers: The Story of Success (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2008), p. 111.

6 Ibid., pp. 89–90. See also Joel N. Shurkin, Terman’s Kids: The Groundbreaking Study of How the Gifted Grow Up (Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1992), p. 35; Wolfgang Saxon “William B. Shockley, 79, Creator of Transistor and Theory on Race,” New York Times, August 14, 1989, p. D9; J.Y. Smith; “Luis Alvarez, Nobel-Winning Atomic Physicist, Dies,” Washington Post, September 3, 1988, p. B6.

7 Malcolm Gladwell, Outliers, pp. 111–112.

8 Ibid., p. 112.

9 Distinguished economist Richard Rosett was another example. See Thomas Sowell, The Einstein Syndrome: Bright Children Who Talk Late (New York: Basic Books, 2001), pp. 47–48. The best-selling author of Hillbilly Elegy was another. See J.D. Vance, Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis (New York: HarperCollins, 2016) pp. 2, 129–130, 205, 239.

10 Charles Murray, Human Accomplishment: The Pursuit of Excellence in the Arts and Sciences, 800 B.C. to 1950 (New York: HarperCollins, 2003), pp. 98–99.

11 Ibid., p. 99.

12 James Corrigan, “Woods in the Mood to End His Major Drought,” The Daily Telegraph (London), August 5, 2013, pp. 16–17.

13 Charles Murray, Human Accomplishment, p. 102.

14 Ibid., pp. 355–361.

15 John K. Fairbank and Edwin O. Reischauer, China: Tradition & Transformation (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1978), p. 17.

16 William D. Altus, “Birth Order and Its Sequelae,” Science, Vol. 151 (January 7, 1966), p. 45.

17 Ibid.

18 Julia M. Rohrer, Boris Egloff, and Stefan C. Schmukle, “Examining the Effects of Birth Order on Personality,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 112, No. 46 (November 17, 2015), p. 14225. These differences in median IQs are not necessarily large. However, even modest differences in median IQs can translate into large disparities in the representation of different groups at IQs of 120 and above—which are the kinds of IQs found among people in elite occupations that attract major attention. Most observers are far less interested in what kinds of people qualify to work behind the counter of fast-food restaurants than they are in what kinds of people are qualified to work in chemistry labs or as engineers or physicians.

19 Lillian Belmont and Francis A. Marolla, “Birth Order, Family Size, and Intelligence,” Science, Vol. 182, No. 4117 (December 14, 1973), p. 1098.

20 Sandra E. Black, Paul J. Devereux and Kjell G. Salvanes, “Older and Wiser? Birth Order and IQ of Young Men,” CESifo Economic Studies, Vol. 57, 1/2011, pp. 103–120.

21 Lillian Belmont and Francis A. Marolla, “Birth Order, Family Size, and Intelligence,” Science, Vol. 182, No. 4117 (December 14, 1973), pp. 1096–1097; Sandra E. Black, Paul J. Devereux and Kjell G. Salvanes, “Older and Wiser? Birth Order and IQ of Young Men,” CESifo Economic Studies, Vol. 57, 1/2011, p. 109.

22 Sidney Cobb and John R.P. French, Jr., “Birth Order Among Medical Students,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 195, No. 4 (January 24, 1966), pp. 172–173.

23 William A. Layman and Andrew Saueracker, “Birth Order and Sibship Size of Medical School Applicants,” Social Psychiatry, Vol. 13 (1978), pp. 117–123.

24 William D. Altus, “Birth Order and Its Sequelae,” Science, Vol. 151 (January 7, 1966), pp. 44–49. See also Robert S. Albert, “The Achievement of Eminence: A Longitudinal Study of Exceptionally Gifted Boys and Their Families,” Beyond Terman: Contemporary Longitudinal Studies of Giftedness and Talent, edited by Rena F. Subotnik and Karen D. Arnold (Norwood, New Jersey: Ablex Publishing Corporation, 1994), p. 293.

25 Alison L. Booth and Hiau Joo Kee, “Birth Order Matters: The Effect of Family Size and Birth Order on Educational Attainment,” Journal of Population Economics, Vol. 22, No. 2 (April 2009), p. 377.

26 Robert J. Gary-Bobo, Ana Prieto and Natalie Picard, “Birth Order and Sibship Sex Composition as Instruments in the Study of Education and Earnings,” Discussion Paper No. 5514 (February 2006), Centre for Economic Policy Research, London, p. 22.

27 Jere R. Behrman and Paul Taubman, “Birth Order, Schooling, and Earnings,” Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 4, No. 3, Part 2: The Family and the Distribution of Economic Rewards (July 1986), p. S136.

28 Philip S. Very and Richard W. Prull, “Birth Order, Personality Development, and the Choice of Law as a Profession,” Journal of Genetic Psychology, Vol. 116, No. 2 (June 1, 1970), pp. 219–221.

29 Richard L. Zweigenhaft, “Birth Order, Approval-Seeking and Membership in Congress,” Journal of Individual Psychology, Vol. 31, No. 2 (November 1975), p. 208.

30 Astronauts and Cosmonauts: Biographical and Statistical Data, Revised August 31, 1993, Report Prepared by the Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress, Transmitted to the Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, U.S. House of Representatives, One Hundred Third Congress, Second Session, March 1994 (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1994), p. 19.

31 Daniel S.P. Schubert, Mazie E. Wagner, and Herman J.P. Schubert, “Family Constellation and Creativity: Firstborn Predominance Among Classical Music Composers,” The Journal of Psychology, Vol. 95, No. 1 (1977), pp. 147–149.

32 Arthur R. Jensen, Genetics and Education (New York: Harper & Row, 1972), p. 143.

33 R.G. Record, Thomas McKeown and J.H. Edwards, “An Investigation of the Difference in Measured Intelligence between Twins and Single Births,” Annals of Human Genetics, Vol. 34, Issue 1 (July 1970), pp. 18, 19, 20.

34 “By age 3, the average child of a professional heard about 500,000 encouragements and 80,000 discouragements. For the welfare children, the situation was reversed: they heard, on average, about 75,000 encouragements and 200,000 discouragements.” Paul Tough, “What it Takes to Make a Student,” New York Times Magazine, November 26, 2006, p. 48. See also Betty Hart and Todd R. Risley, Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children (Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., 1995), p. 253. See also Edward C. Banfield, The Unheavenly City: The Nature and Future of Our Urban Crisis (Boston: Little, Brown, 1970), pp. 224–229.

35 “Choose Your Parents Wisely,” The Economist, July 26, 2014, p. 22.

36 See, for example, Kay S. Hymowitz, Marriage and Caste in America: Separate and Unequal Families in a Post-Marital Age (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006), pp. 78–82; Betty Hart and Todd R. Risley, Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children, p. 253; Edward C. Banfield, The Unheavenly City, pp. 224–229. It is painful to contemplate the prospects of a child born to a single mother on welfare who has failed to finish high school. Lacking the interactions of a father is not without consequences. “We find that after accounting for parental education, skills, and income, both a father’s and a mother’s time investment in the first five years of a child’s life have a large effect on the child’s completed education.” George-Levi Gayle, Limor Golan, and Mrhmet A. Soytas, “Intergenerational Mobility and the Effects of Parental Education, Time Investment, and Income on Children’s Educational Attainment,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, Volume 100, No. 3 (Third Quarter 2018), p. 292.

37 For examples and a fuller discussion of social mobility see Thomas Sowell, Wealth, Poverty and Politics, revised and enlarged edition (New York: Basic Books, 2016), pp. 178–183, 360–375, 382–390.

38 Henry Thomas Buckle, On Scotland and the Scotch Intellect (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970), p. 52.

39 Irokawa Daikichi, The Culture of the Meiji Period, translated and edited by Marius B. Jansen (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985), p. 7.

40 Joel Mokyr, A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017), p. 256.

41 Steven Beller, “Big-City Jews: Jewish Big City—the Dialectics of Jewish Assimilation in Vienna, c. 1900,” The City in Central Europe: Culture and Society from 1800 to the Present, edited by Malcolm Gee, Tim Kirk and Jill Steward (Brookfield, Vermont: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 1999), p. 150.

42 Charles Murray, Human Accomplishment, pp. 280, 282.

43 Charles O. Hucker, China’s Imperial Past: An Introduction to Chinese History and Culture (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1975), p. 65; Jacques Gernet, A History of Chinese Civilization, second edition, translated by J.R. Foster and Charles Hartman (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 69.

44 David S. Landes, The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some So Poor (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1998), pp. 93–95; William H. McNeill, The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), p. 526.

45 David S. Landes, The Wealth and Poverty of Nations, pp. 94–95.

46 See, for examples, Thomas Sowell, Wealth, Poverty and Politics, revised and enlarged edition, especially Part I; Ellen Churchill Semple, Influences of Geographic Environment (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1911), pp. 144, 175, 397, 530, 531, 599, 600. By contrast, she refers to “the cosmopolitan civilization characteristic of coastal regions.” Ibid., p. 347.

47 Andrew Tanzer, “The Bamboo Network,” Forbes, July 18, 1994, pp. 138–144; “China: Seeds of Subversion,” The Economist, May 28, 1994, p. 32.

48 Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1986), pp. 13, 106, 188–189, 305–314; Silvan S. Schweber, Einstein and Oppenheimer: The Meaning of Genius (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2008), p. 138; Michio Kaku, Einstein’s Cosmos: How Albert Einstein’s Vision Transformed Our Understanding of Space and Time (New York: W.W. Norton, 2004), pp. 187–188; Howard M. Sachar, A History of the Jews in America (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992), p. 527; American Jewish Historical Society, American Jewish Desk Reference (New York: Random House, 1999), p. 591.

49 Quoted in Bernard Lewis, The Muslim Discovery of Europe (New York: W.W. Norton, 1982), p. 139.

50 Giovanni Gavetti, Rebecca Henderson and Simona Giorgi, “Kodak and the Digital Revolution (A),” 9–705–448, Harvard Business School, November 2, 2005, pp. 3, 11.

51 “The Last Kodak Moment?” The Economist, January 14, 2012, pp. 63–64.

52 Mike Spector and Dana Mattioli, “Can Bankruptcy Filing Save Kodak?” Wall Street Journal, January 20, 2012, p. B1.

53 Henry C. Lucas, Jr., Inside the Future: Surviving the Technology Revolution (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2008), p. 157.

54 Giovanni Gavetti, Rebecca Henderson and Simona Giorgi, “Kodak and the Digital Revolution (A),” 9–705–448, Harvard Business School, November 2, 2005, p. 4.

55 Ibid., p. 12.

56 More than half a century before the collapse of Eastman Kodak, economist J.A. Schumpeter pointed out that the most powerful economic competition is not that between producers of the same product, as so often assumed, but the competition between old and new technologies and methods of organization. In the case of Eastman Kodak, it was not the competition of Fuji film, but the competition of digital cameras, that was decisive. For Schumpeter, it was not the competition of firms producing the same products, as in economics textbooks, that was decisive. In Schumpeter’s words, “it is not that kind of competition which counts but the competition from the new commodity, the new technology, the new source of supply, the new type of organization (the largest-scale unit of control, for instance)—competition which commands a decisive cost or quality advantage and which strikes not at the margins of the profits and the outputs of the existing firms but at their foundations and their very lives.” Joseph A. Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, third edition (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1950), p. 84. Among other examples were the A&P chain of grocery stores that was for years the largest chain of retail stores of any kind, anywhere in the world. Eventually new competitors “competed against A&P not by doing better what A&P was the best company in the world at doing,” but by organizing their businesses in very different ways that all but obliterated A&P. Richard S. Tedlow, New and Improved: The Story of Mass Marketing in America (New York: Basic Books, 1990), p. 246.

57 Darrell Hess, McKnight’s Physical Geography: A Landscape Appreciation, eleventh edition (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc., 2014), p. 200.

58 Africa: Atlas of Our Changing Environment (Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Environment Programme, 2008), p. 29; Rachel I. Albrecht, Steven J. Goodman, Dennis E. Buechler, Richard J. Blakeslee and Hugh J. Christian, “Where Are the Lightning Hotspots on Earth?” Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, November 2016, p. 2055; The New Encyclopædia Britannica (Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2005), Volume 3, p. 583.

59 Darrell Hess, McKnight’s Physical Geography, eleventh edition, p. 198.

60 Alan H. Strahler, Introducing Physical Geography, sixth edition (Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley, 2013), pp. 402–403.

61 Bradley C. Bennett, “Plants and People of the Amazonian Rainforests,” BioScience, Vol. 42, No. 8 (September 1992), p. 599.

62 Ronald Fraser, “The Amazon,” Great Rivers of the World, edited by Alexander Frater (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1984), p. 111.

63 Karen Kaplan, “Man, Chimp Separated by a Dab of DNA,” Los Angeles Times, September 1, 2005, p. A12; Rick Weiss, “Scientists Complete Genetic Map of the Chimpanzee,” Washington Post, September 1, 2005, p. A3; “A Creeping Success,” The Economist, June 5, 1999, pp. 77–78.

64 David S. Landes, The Wealth and Poverty of Nations, p. 6.

65 A.H.M. Jones, The Later Roman Empire 284–602: A Social and Administrative Survey (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1964), Volume 2, pp. 841–842.

66 Ellen Churchill Semple, The Geography of the Mediterranean Region: Its Relation to Ancient History (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1931), p. 5.

67 Jack Chen, The Chinese of America (San Francisco: Harper & Row Publishers, 1980), pp. 65–66.

68 See, for example, Ellen Churchill Semple, Influences of Geographic Environment, pp. 20, 280, 281–282, 347, 521–531, 599, 600; Fernand Braudel, The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, translated by Siân Reynolds (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), Vol. I, pp. 34, 35; Thomas Sowell, Wealth, Poverty and Politics, revised and enlarged edition, pp. 45–54.

69 James S. Gardner, et al., “People in the Mountains,” Mountain Geography: Physical and Human Dimensions, edited by Martin F. Price, et al (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), pp. 288–289; J.R. McNeill, The Mountains of the Mediterranean World: An Environmental History (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992), pp. 223, 225–227; Ellen Churchill Semple, Influences of Geographic Environment, pp. 578–579.

70 See, for example, Frederick R. Troeh and Louis M. Thompson, Soils and Soil Fertility, sixth edition (Ames, Iowa: Blackwell, 2005), p. 330; Xiaobing Liu, et al., “Overview of Mollisols in the World: Distribution, Land Use and Management,” Canadian Journal of Soil Science, Vol. 92 (2012), pp. 383–402; Darrel Hess, McKnight’s Physical Geography, eleventh edition, pp. 362–363.

71 Andrew D. Mellinger, Jeffrey D. Sachs, and John L. Gallup, “Climate, Coastal Proximity, and Development,” The Oxford Handbook of Economic Geography, edited by Gordon L. Clark, Maryann P. Feldman and Meric S. Gertler (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 169. Nearly a century earlier, a geographic treatise declared that, as a general rule, “the coasts of a country are the first part of it to develop.” Ellen Churchill Semple, Influences of Geographic Environment, p. 280.

72 See, for documented examples, Thomas Sowell, Wealth, Poverty and Politics, revised and enlarged edition, Section I. See also Ellen Churchill Semple, Influences of Geographic Environment, especially chapters on coastal peoples (VIII), island peoples (XIII), peoples in river valleys (XI) and peoples in hills and mountains around the world (XV and XVI).

73 James S. Gardner, et al., “People in the Mountains,” Mountain Geography, edited by Martin F. Price, et al., p. 268.

74 The world population in 2014 was 7.2 billion people. The population of the United States that year was 323 million people, while the population of Italy was 61 million people. The Economist, Pocket World in Figures: 2017 edition (London: Profile Books, 2016), pp. 14, 240.

75 Edward C. Banfield, The Moral Basis of a Backward Society (New York: The Free Press, 1958), pp. 35, 46–47.

76 Fernand Braudel, A History of Civilizations, translated by Richard Mayne (New York: The Penguin Press, 1994), p. 17.

77 Donald L. Horowitz, Ethnic Groups in Conflict (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), p. 677.

78 Myron Weiner, “The Pursuit of Ethnic Equality Through Preferential Policies: A Comparative Public Policy Perspective,” From Independence to Statehood, edited by Robert B. Goldmann and A. Jeyaratnam Wilson (London: Frances Pinter, 1984), p. 64.

79 Cynthia H. Enloe, Police, Military and Ethnicity: Foundations of State Power (New Brunswick: Transaction Books, 1980), p. 143.

80 Angelo M. Codevilla, The Character of Nations: How Politics Makes and Breaks Prosperity, Family, and Civility (New York: Basic Books, 1997), p. 50.

81 Charles Murray, Human Accomplishment, p. 298.

82 Ibid., pp. 304, 305.

83 U.S. Bureau of the Census data show the median household income of people aged 45 to 54 to be double that of the median household income of people less than 25 years old. But white household income is less than double that of black household income. Kayla Fontenot, Jessica Semega and Melissa Kollar, “Income and Poverty in the United States: 2017,” Current Population Reports, P60–263 (Washington: U.S. Census Bureau, 2018), Table 1, p. 2. So are median weekly earnings of full-time workers. “Usual Weekly Earnings of Wage and Salary Workers First Quarter 2017,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, April 18, 2017, Table 3.

84 See U.S. Census Bureau, S0201, Selected Population Profile in the United States, 2016 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, downloaded from the Census website on July 9, 2018: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_16_1YR_S0201&prodType=table.

85 For documented specifics, see Thomas Sowell, Intellectuals and Race (New York: Basic Books, 2013), Chapter 3.

86 Thomas C. Leonard, “Eugenics and Economics in the Progressive Era,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 19, No. 4 (Fall 2005), p. 216.

87 Sidney Webb, “Eugenics and the Poor Law: The Minority Report,” Eugenics Review, Vol. II (April 1910-January 1911), p. 240; Thomas C. Leonard, “Eugenics and Economics in the Progressive Era,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 19, No. 4 (Fall 2005), p. 216; Richard Overy, The Twilight Years: The Paradox of Britain Between the Wars (New York: Viking, 2009), pp. 93, 105, 106, 107, 124–127; Donald MacKenzie, “Eugenics in Britain,” Social Studies of Science, Vol. 6, No. 3–4 (September 1975), p. 518; Jakob Tanner, “Eugenics Before 1945,” Journal of Modern European History, Vol. 10, No. 4 (2012), p. 465.

88 For documented specifics, see Thomas Sowell, Intellectuals and Race, pp. 29–35.

89 Leon J. Kamin, The Science and Politics of I.Q. (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1974), p. 6.

90 Carl C. Brigham, A Study of American Intelligence (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1923), p. 190.

91 The World Almanac and Book of Facts: 2013 (New York: World Almanac Books, 2013), p. 335.

92 E.A. Pearce and C.G. Smith, The Times Books World Weather Guide (New York: Times Books, 1984), pp. 279, 380, 413.

93 Ibid., pp. 132, 376. In none of the winter months—from December through March—is the average daily low temperature in Washington warmer than in London, and the lowest temperature ever recorded in Washington is lower for each of those winter months than in London.

94 For documented specifics, see Thomas Sowell, Wealth, Poverty and Politics, revised and enlarged edition, pp. 62–64.

95 Steven Pinker, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (New York: Viking, 2011), pp. 85–87.

96 “Solving Murder,” The Economist, April 7, 2018, p. 9.

Chapter 2: DISCRIMINATION: MEANINGS AND COSTS

1 Harry J. Holzer, Steven Raphael, and Michael A. Stoll, “Perceived Criminality, Criminal Background Checks, and the Racial Hiring Practices of Employers,” Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 49, No. 2 (October 2006), pp. 452, 473. See also Gail L. Heriot, “Statement of Commissioner Gail Heriot in the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights’ Report, “Assessing the Impact of Criminal Background Checks and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Conviction Records Policy,” Legal Studies Research Paper Series, Research Paper No. 17–251 (San Diego: University of San Diego Law School, 2013); Jennifer L. Doleac and Benjamin Hansen, “The Unintended Consequences of ‘Ban the Box’: Statistical Discrimination and Employment Outcomes When Criminal Histories Are Hidden,” Social Science Research Network, last revised August 22, 2018.

2 See, for example, Zy Weinberg, “No Place to Shop: Food Access Lacking in the Inner City,” Race, Poverty & the Environment, Vol. 7, No. 2 (Winter 2000), pp. 22–24; Michael E. Porter, “The Competitive Advantage of the Inner City,” Harvard Business Review, May-June 1995, pp. 63–64; James M. MacDonald and Paul E. Nelson, Jr., “Do the Poor Still Pay More? Food Price Variations in Large Metropolitan Areas,” Journal of Urban Economics, Vol. 30 (1991), pp. 349, 350, 357; Donald R. Marion, “Toward Revitalizing Inner-City Food Retailing,” National Food Review, Summer 1982, pp. 22, 23, 24.

3 David Caplovitz, The Poor Pay More: Consumer Practices of Low-Income Families (New York: The Free Press, 1967), p. xvi.

4 See, for example, “Democrats Score A.&P. Over Prices,” New York Times, July 18, 1963, p. 11; Elizabeth Shelton, “Prices Are Never Right,” Washington Post, December 4, 1964, p. C3; “Gouging the Poor,” New York Times, August 13, 1966, p. 41; “Overpricing of Food in Slums Is Alleged at House Hearing,” New York Times, October 13, 1967, p. 20; “Ghetto Cheats Blamed for Urban Riots,” Chicago Tribune, February 18, 1968, p. 8; “Business Leaders Urge Actions to Help Poor,” Los Angeles Times, April 11, 1968, p. C13; Frederick D. Sturdivant and Walter T. Wilhelm, “Poverty, Minorities, and Consumer Exploitation,” Social Science Quarterly, Vol. 49, No. 3 (December 1968), p. 650.

5 Donald R. Marion, “Toward Revitalizing Inner-City Food Retailing,” National Food Review, Summer 1982, pp. 23–24. “Sales in urban stores are 13 percent lower by volume, and operating costs are 9 percent higher. Profits, before taxes, are less than half of the suburban stores. Labor costs are higher, shrinkage costs are greater, sales per customer are lower, insurance and repair costs are higher, and losses due to crime are more than doubled in the inner-city stores.” Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Agricultural Production, Marketing, and Stabilization of Prices of the Committee on Agriculture and Forestry, United States Senate, Ninety-Fourth Congress, Second Session, June 23 and 25, 1976 (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1976), p. 57. See also pp. 116, 124–125.

6 Dorothy Height, “A Woman’s Word,” New York Amsterdam News, July 24, 1965, p. 34.

7 Ray Cooklis, “Lowering the High Cost of Being Poor,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 28, 2009, p. A7.

8 Jonathan Gill, Harlem: The Four Hundred Year History from Dutch Village to Capital of Black America (New York: Grove Press, 2011), p. 119.

9 See U.S. Census Bureau, S0201, Selected Population Profile in the United States, 2016 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, downloaded from the Census website on July 9, 2018: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_16_1YR_S0201&prodType=table.

10 “Choose Your Parents Wisely,” The Economist, July 26, 2014, p. 22. “We find that after accounting for parental education, skills, and income, both a father’s and a mother’ time investment in the first five years of a child’s life have a large effect on the child’s completed education.” George-Levi Gayle, Limor Golan, and Mehmet A. Soytas, “Intergenerational Mobility and the Effects of Parental Education, Time Investment and Income on Children’s Educational Attainment,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, Volume 100, No. 3 (Third Quarter 2018), pp. 291–292.

11 The Chronicle of Higher Education: Almanac 2017–2018, August 18, 2017, p. 46.

12 Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Selected Correspondence 1846–1895, translated by Dona Torr (New York: International Publishers, 1942), p. 476.

13 Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (New York: Modern Library, 1937), p. 423.

14 Adam Smith denounced “the mean rapacity, the monopolizing spirit of merchants and manufacturers” and “the clamour and sophistry of merchants and manufacturers,” whom he characterized as people who “seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public.” As for policies recommended by such people, Smith said: “The proposal of any new law or regulation of commerce which comes from this order, ought always to be listened to with great precaution, and ought never to be adopted till after having been long and carefully examined, not only with the most scrupulous, but with the most suspicious attention. It comes from an order of men, whose interest is never exactly the same with that of the public, who have generally an interest to deceive and even to oppress the public, and who accordingly have, upon many occasions, both deceived and oppressed it.” Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, pp. 128, 250, 460. Karl Marx wrote, in the preface to the first volume of Capital: “I paint the capitalist and the landlord in no sense couleur de rose. But here individuals are dealt with only in so far as they are the personifications of economic categories, embodiments of particular class-relations and class-interests. My stand-point, from which the evolution of the economic formation of society is viewed as a process of natural history, can less than any other make the individual responsible for relations whose creature he socially remains, however much he may subjectively raise himself above them.” In Chapter X, Marx made dire predictions about the fate of workers, but not as a result of subjective moral deficiencies of the capitalist, for Marx said: “As capitalist, he is only capital personified” and “all this does not, indeed, depend on the good or ill will of the individual capitalist.” Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1909), Vol. I, pp. 15, 257, 297.

15 William Julius Wilson, The Declining Significance of Race: Blacks and Changing American Institutions, third edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), pp. 52–53, 54–55, 59.

16 Robert Higgs, Competition and Coercion: Blacks in the American Economy 1865–1914 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1977), pp. 47–49, 130–131.

17 In many cases, they did not have to literally go anywhere because, in an era where many blacks in the rural South had no access to either public or private transportation, white landlords or employers either went, or sent an emissary, to where black workers were congregated, and announced what work was available and on what terms. Even in some urban settings today, similar recruitment patterns occur in the hiring of casual day laborers.

18 Robert Higgs, Competition and Coercion, pp. 102, 144–146.

19 Ibid., p. 117.

20 Walter E. Williams, South Africa’s War Against Capitalism (New York: Praeger, 1989), pp. 101, 102, 103, 104, 105. See also Brian Lapping, Apartheid: A History (New York : G. Braziller, 1987), p. 164; Merle Lipton, Capitalism and Apartheid: South Africa, 1910–1984 (Aldershot, Hants, England: Gower, 1985), pp. 152, 153.

21 The book that resulted from this research was Walter E. Williams, South Africa’s War Against Capitalism.

22 Ibid., pp. 112, 113.

23 See, for example, Thomas Sowell, Applied Economics: Thinking Beyond Stage One, revised and enlarged edition (New York: Basic Books, 2009), Chapter 7; Thomas Sowell, Economic Facts and Fallacies (New York: Basic Books, 2008), pp. 73–75, 123, 170–172.

24 Jennifer Roback, “The Political Economy of Segregation: The Case of Segregated Streetcars,” Journal of Economic History, Vol. 46, No. 4 (December 1986), pp. 893–917.

25 Ibid., pp. 894, 899–901, 903, 904, 912, 916.

26 Kermit L. Hall and John J. Patrick, The Pursuit of Justice: Supreme Court Decisions that Shaped America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 59–64; Michael J. Klarman, From Jim Crow to Civil Rights: The Supreme Court and the Struggle for Racial Equality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 8.

27 Bernard E. Anderson, Negro Employment in Public Utilities: A Study of Racial Policies in the Electric Power, Gas, and Telephone Industries (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1970), pp. 73, 80.

28 Ibid., pp. 93–95.

29 Venus Green, Race on the Line: Gender, Labor, and Technology in the Bell System, 1880–1980 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2001), p. 210.

30 Bernard E. Anderson, Negro Employment in Public Utilities, pp. 84–87, 150, 152.

31 Ibid., pp. 150, 152. During the 1950s, the percentage of male employees in the telecommunications industry who were black actually fell in such Southern states as Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia. Ibid., pp. 84–87.

32 Ibid., pp. 114, 139.

33 Michael R. Winston, “Through the Back Door: Academic Racism and the Negro Scholar in Historical Perspective,” Daedalus, Vol. 100, No. 3 (Summer 1971), pp. 695, 705.

34 Milton & Rose D. Friedman, Two Lucky People: Memoirs (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), pp. 91–92, 94–95, 105–106, 153–154.

35 Greg Robinson, “Davis, Allison,” Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History, edited by Colin A. Palmer (Detroit: Thomson-Gale, 2006), Volume C–F, p. 583; “The Talented Black Scholars Whom No White University Would Hire,” Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, No. 58 (Winter 2007/2008), p. 81.

36 George J. Stigler, “The Economics of Minimum Wage Legislation,” American Economic Review, Vol. 36, No. 3 (June 1946), p. 358.

37 Walter E. Williams, Race & Economics: How Much Can Be Blamed on Discrimination (Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 2011), pp. 42–43.

38 Ibid.; Edward C. Banfield, The Unheavenly City: The Nature and Future of Our Urban Crisis (Boston: Little, Brown, 1970), p. 98.

39 Charles Murray, Losing Ground: American Social Policy, 1950–1980 (New York: Basic Books, 1984), p. 77; Walter E. Williams, Race & Economics, p. 44.

40 Chas Alamo and Brian Uhler, California’s Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences (Sacramento: Legislative Analyst’s Office, 2015), pp. 9, 11–12, 14.

41 Sandra Fleishman, “High Prices? Cheaper Here Than Elsewhere,” Washington Post, January 8, 2005, p. F1; Jason B. Johnson, “Making Ends Meet: Struggling in Middle Class,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 16, 2005, p. A11.

42 Stephen Coyle, “Palo Alto: A Far Cry from Euclid,” Land Use and Housing on the San Francisco Peninsula, edited by Thomas M. Hagler (Stanford: Stanford Environmental Law Society, 1983), pp. 85, 89.

43 Leslie Fulbright, “S.F. Moves to Stem African American Exodus,” San Francisco Chronicle, April 9, 2007, p. A1.

44 Bureau of the Census, 1990 Census of Population: General Population Characteristics California, 1990 CP–1–6, Section 1 of 3, pp. 27, 28, 31; U.S. Census Bureau, Profiles of General Demographic Characteristics 2000: 2000 Census of Population and Housing, California, Table DP–1, pp. 2, 20, 42.

45 Gilbert Osofsky, Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto, Negro New York 1890–1930 (New York: Harper & Row, 1966), pp. 106–110; Jonathan Gill, Harlem, pp. 180–184.

46 Gilbert Osofsky, Harlem, p. 110.

Chapter 3: SORTING AND UNSORTING PEOPLE

1 Joses C. Moya, Cousins and Strangers: Spanish Immigrants in Buenos Aires, 1850–1930 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), pp. 119, 145–146. Similarly, most of the Italian immigrants to Australia, between 1881 and 1899, came from places containing only 10 percent of the population of Italy. Helen Ware, A Profile of the Italian Community in Australia (Melbourne: Australian Institute of Multicultural Affairs and Co.As.It Italian Assistance Association, 1981), p. 12.

2 Australia’s eminent historian of immigration, Professor Charles A. Price, pointed out long ago that “immigrants rarely come in equal proportions from all parts of the country of origin, but rather in bunches from a few districts here and there. One of the main reasons for this is chain migration, the process whereby one member of a family, village, or township successfully establishes himself abroad and then writes to one or two friends and relatives at home encouraging them to come and join him, frequently helping with housing, jobs, and passage expenses. The few who join him then write home in their turn, so setting off a ‘chain’ system of migration that may send hundreds of persons from one small district of origin to one relatively confined area in the country of settlement.” Charles A. Price, Jewish Settlers in Australia (Canberra: The Australian National University, 1964), p. 21.

3 Jonathan Gill, Harlem: The Four Hundred Year History from Dutch Village to Capital of Black America (New York: Grove Press, 2011), p. 140; Charles A. Price, Southern Europeans in Australia (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1963), p. 162; Philip Taylor, The Distant Magnet: European Emigration to the USA (New York: Harper & Row, 1971), pp. 210, 211; Dino Cinel, From Italy to San Francisco: The Immigrant Experience (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1982), pp. 28, 117–120; Samuel L. Baily, “The Adjustment of Italian Immigrants in Buenos Aires and New York, 1870–1914,” American Historical Review, April 1983, p. 291; John E. Zucchi, Italians in Toronto: Development of a National Identity, 1875–1935 (Kingston, Ontario: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1988), pp. 41, 53–55, 58.

4 Moses Rischin, The Promised City: New York’s Jews 1870–1914 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1962), pp. 76, 85–108, 238–239.

5 Annie Polland and Daniel Soyer, Emerging Metropolis: New York Jews in the Age of Immigration, 1840–1920 (New York: New York University Press, 2012), p. 31; Tyler Anbinder, City of Dreams: The 400-Year Epic History of Immigrant New York (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016), pp. 174–175, 178, 356, 358; Stephen Birmingham, “The Rest of Us”: The Rise of America’s Eastern European Jews (Boston: Little, Brown, 1984), pp. 12–24.

6 Louis Wirth, The Ghetto (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956), pp. 182–184; Irving Cutler, “The Jews of Chicago: From Shetl to Suburb,” Ethnic Chicago: A Multicultural Portrait, fourth edition, edited by Melvin G. Holli and Peter d’A. Jones (Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1995), pp. 127–129, 134–135, 143–144.

7 Fred Rosenbaum, Visions of Reform: Congregation Emanu-El and the Jews of San Francisco, 1849–1999 (Berkeley: Judah L. Magnes Museum, 2000), pp. 59–60, 184.

8 William A. Braverman “The Emergence of a Unified Community, 1880–1917,” The Jews of Boston, edited by Jonathan D. Sarna, Ellen Smith and Scott-Martin Kosofsky (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), p. 66. Both the German Jews and the Polish Jews moved out when the Russian Jews moved in. The Polish Jews in this case were from German-ruled areas, there being no Poland at the time, and were apparently more culturally like German Jews than like Russian Jews.

9 Daniel J. Elazar and Peter Medding, Jewish Communities in Frontier Societies: Argentina, Australia, and South Africa (New York: Holmes & Meier, 1983), pp. 263–264, 332–334; Hilary L. Rubinstein, The Jews in Victoria: 1835–1985 (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1986), Chapters 10–12. One sign of these internal differences was a saying among Australian Jews that Sydney was a warm city with cold Jews, while Melbourne was a cold city with warm Jews. Hilary Rubinstein, Chosen: The Jews in Australia (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1987), p. 220.

10 H.L. van der Laan, The Lebanese Traders in Sierra Leone (The Hague: Mouton & Co., 1975), pp. 237–240; Louise L’Estrange Fawcett, “Lebanese, Palestinians and Syrians in Colombia,” The Lebanese in the World: A Century of Emigration, edited by Albert Hourani and Nadim Shehadi (London: The Centre for Lebanese Studies, 1992), p. 368.

11 Tyler Anbinder, City of Dreams, pp. 176–177.

12 Teiiti Suzuki, The Japanese Immigrant in Brazil: Narrative Part (Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1969), p. 109.

13 Tyler Anbinder, City of Dreams, p. 185.

14 Charles A. Price, The Methods and Statistics of ‘Southern Europeans in Australia’ (Canberra: The Australian National University, 1963), p. 45.

15 E. Franklin Frazier, “The Negro Family in Chicago,” E. Franklin Frazier on Race Relations: Selected Writings, edited by G. Franklin Edwards (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968), pp. 122–126.

16 E. Franklin Frazier, “The Impact of Urban Civilization Upon Negro Family Life,” American Sociological Review, Vol. 2, No. 5 (October 1937), p. 615.

17 David M. Katzman, Before the Ghetto: Black Detroit in the Nineteenth Century (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1973), p. 27.

18 Kenneth L. Kusmer, A Ghetto Takes Shape: Black Cleveland, 1870–1930 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), p. 209.

19 Jonathan Gill, Harlem, p. 284.

20 Andrew F. Brimmer, “The Labor Market and the Distribution of Income,” Reflections of America: Commemorating the Statistical Abstract Centennial, edited by Norman Cousins (Washington: U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, 1980), pp. 102–103.

21 Rakesh Kochhar and Anthony Cilluffo, Income Inequality in the U.S. Is Rising Most Rapidly Among Asians (Washington: Pew Research Center, 2018), p. 4. See also William Julius Wilson, When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996), p. 195.

22 Horace Mann Bond, A Study of Factors Involved in the Identification and Encouragement of Unusual Academic Talent among Underprivileged Populations (U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, January 1967), p. 147. [Contract No. SAE 8028, Project No. 5–0859].

23 Ibid.

24 See, for example, Willard B. Gatewood, Aristocrats of Color: The Black Elite, 1880–1920 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), pp. 188–189, 247; David M. Katzman, Before the Ghetto, Chapter V; Theodore Hershberg and Henry Williams, “Mulattoes and Blacks: Intra-Group Differences and Social Stratification in Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia,” Philadelphia: Work, Space, Family, and Group Experience in the Nineteenth Century, edited by Theodore Hershberg (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981), pp. 392–434.

25 Stephen Birmingham, Certain People: America’s Black Elite (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1977), pp. 196–197. As a personal note, I delivered groceries to people in that building during my teenage years, entering through the service entrance in the basement, rather than through the canopied front entrance with its uniformed doorman and ornate lobby. My own home was in a tenement apartment some distance away.

26 St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton, Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City, revised and enlarged edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), pp. 73–74; James R. Grossman, “African-American Migration to Chicago,” Ethnic Chicago, fourth edition, edited by Melvin G. Holli and Peter d’A. Jones, pp. 323, 332, 333–334; Henri Florette, Black Migration: Movement North, 1900–1920 (Garden City, New York: Anchor Press, 1975), pp. 96–97; Allan H. Spear, Black Chicago: The Making of a Negro Ghetto, 1890–1920 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967), p. 168.

27 James R. Grossman, “African-American Migration to Chicago,” Ethnic Chicago, fourth edition, edited by Melvin G. Holli and Peter d’A. Jones, pp. 323, 330, 332, 333–334; Willard B. Gatewood, Aristocrats of Color, pp. 186–187, 332; Allan H. Spear, Black Chicago, p. 168; E. Franklin Frazier, The Negro in the United States, revised edition (New York: Macmillan, 1957), p. 284; Henri Florette, Black Migration, pp. 96–97; Gilbert Osofsky, Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto, Negro New York 1890–1930 (New York: Harper & Row, 1966), pp. 43–44; Ivan H. Light, Ethnic Enterprise in America: Business and Welfare Among Chinese, Japanese, and Blacks (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972), Figure 1 (after p. 100); W.E.B. Du Bois, The Black North in 1901: A Social Study (New York: Arno Press, 1969), p. 25.

28 James R. Grossman, “African-American Migration to Chicago,” Ethnic Chicago, fourth edition, edited by Melvin G. Holli and Peter d’A. Jones, p. 331. See also Ethan Michaeli, The Defender: How the Legendary Black Newspaper Changed America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016), p. 84.

29 Willard B. Gatewood, Aristocrats of Color, pp. 186–187; James R. Grossman, “African-American Migration to Chicago,” Ethnic Chicago, fourth edition, edited by Melvin G. Holli and Peter d’A. Jones, pp. 323, 330; St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton, Black Metropolis, revised and enlarged edition, pp. 73–74.

30 E. Franklin Frazier, The Negro in the United States, revised edition, p. 643.

31 According to Professor Steven Pinker, “the North-South difference is not a byproduct of the white-black difference. Southern whites are more violent than northern whites, and southern blacks are more violent than northern blacks.” Steven Pinker, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (New York: Viking, 2011), p. 94.

32 Davison M. Douglas, Jim Crow Moves North: The Battle over Northern School Segregation, 1865–1954 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), pp. 2–5, 61–62; Willard B. Gatewood, Aristocrats of Color, p. 250; E. Franklin Frazier, The Negro in the United States, revised edition, p. 441.

33 Willard B. Gatewood, Aristocrats of Color, pp. 64, 65, 300–301; E. Franklin Frazier, The Negro in the United States, revised edition, pp. 250–251.

34 Davison M. Douglas, Jim Crow Moves North, pp. 128, 129; Kenneth L. Kusmer, A Ghetto Takes Shape, pp. 57, 64–65, 75–76, 80, 178–179. In St. Louis and Chicago, the number of restrictive covenants skyrocketed during the great migrations at around the time of the First World War. Michael Jones-Correa, “The Origins and Diffusion of Racial Restrictive Covenants,” Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 115, No. 4 (Winter 2000–2001), p. 558.

35 Davison M. Douglas, Jim Crow Moves North, pp. 130–131; Willard B. Gatewood, Aristocrats of Color, p. 147.

36 James N. Gregory, The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), p. 123; Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (New York: Random House, 2010), p. 291; Carl Wittke, The Irish in America (New York: Russell & Russell, 1970), pp. 101–102; Oscar Handlin, Boston’s Immigrants (New York: Atheneum, 1970), pp. 169–170; Jay P. Dolan, The Irish Americans: A History (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2008), pp. 118–119; Irving Howe, World of Our Fathers: The Journey of the East European Jews to America and the Life They Found and Made (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976), pp. 229–230.

37 Daniel J. Elazar and Peter Medding, Jewish Communities in Frontier Societies, pp. 282–283.

38 Marilynn S. Johnson, The Second Gold Rush: Oakland and the East Bay in World War II (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), p. 198.

39 Douglas Henry Daniels, Pioneer Urbanites: A Social and Cultural History of Black San Francisco (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1980), pp. 50, 75, 77, 97.

40 Marilynn S. Johnson, The Second Gold Rush, p. 52.

41 Ibid., p. 55.

42 Douglas Henry Daniels, Pioneer Urbanites, p. 165.

43 Marilynn S. Johnson, The Second Gold Rush, pp. 95–96, 152, 170; E. Franklin Frazier, The Negro in the United States, revised edition, p. 270; Douglas Henry Daniels, Pioneer Urbanites, pp. 171–175.

44 E. Franklin Frazier, The Negro in the United States, revised edition, p. 270.

45 Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1944), p. 965.

46 Arthur R. Jensen, Genetics and Education (New York: Harper & Row, 1972), pp. 106–107, 129–130.

47 Mya Frazier, “After the Walmart Is Gone,” Bloomberg Businessweek, October 16, 2017, p. 59.

48 William Julius Wilson, More Than Just Race: Being Black and Poor in the Inner City (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009), pp. 1–2.

49 Walter E. Williams, Race & Economics: How Much Can Be Blamed on Discrimination (Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 2011), p. 117.

50 So did Paul R. Williams in the early twentieth century, when he decided to become an architect, at a time when such a career seemed all but impossible for a black man. He said: “White Americans have a reasonable basis for their prejudice against the Negro race, and if that prejudice is ever to be overcome it must be through the efforts of individual Negroes to rise above the average cultural level of their kind. Therefore, I owe it to myself and to my people to accept this challenge.” He went on to have a highly successful career as an architect, designing everything from banks and churches to mansions for Hollywood movie stars. See Karen E. Hudson, Paul R. Williams, Architect: A Legacy of Style (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1993), p. 12.

51 See, for example, Christopher Silver, “The Racial Origins of Zoning in American Cities,” Urban Planning and the African American Community: In the Shadows, edited by June Manning Thomas and Marsha Ritzdorf (Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1997), pp. 23–42; Michael Jones-Correa, “The Origins and Diffusion of Racial Restrictive Covenants,” Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 115, No. 4 (Winter 2000–2001), pp. 541–568.

52 See Abbot Emerson Smith, Colonists in Bondage: White Servitude and Convict Labor in America 1607–1776 (Gloucester, Massachusetts: Peter Smith, 1965), pp. 3–4.

53 E. Franklin Frazier, The Negro in the United States, revised edition, pp. 22–26; John Hope Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of American Negroes, second edition (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1947), pp. 70–72.

54 St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton, Black Metropolis, revised and enlarged edition, pp. 44–45.

55 David M. Katzman, Before the Ghetto, pp. 35, 69, 102, 200.

56 Ibid., p. 160; Willard B. Gatewood, Aristocrats of Color, p. 125.

57 W.E.B. Du Bois, The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study (New York: Schocken Books, 1967), pp. 7, 41–42, 305–306.

58 Jacob Riis, How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1970), p. 99; David M. Katzman, Before the Ghetto, pp. 35, 37, 138, 139, 160; St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton, Black Metropolis, revised and enlarged edition, pp. 44–45; Willard B. Gatewood, Aristocrats of Color, p. 125.

59 Davison M. Douglas, Jim Crow Moves North, p. 3.

60 Jacob Riis, How the Other Half Lives, p. 99.

61 Davison M. Douglas, Jim Crow Moves North, p. 3.

62 Ibid., pp. 155–156.

63 Ibid., pp. 154.

64 For documentation, see Thomas C. Leonard, Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics & American Economics in the Progressive Era (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), pp. 119–124; Thomas Sowell, Intellectuals and Race (New York: Basic Books, 2013), pp. 24–43.

65 See, for example, Jacqueline A. Stefkovich and Terrence Leas, “A Legal History of Desegregation in Higher Education,” Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 63, No. 3 (Summer 1994), pp. 409–410.

66 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), at 495.

67 Ibid., at 494.

68 T. Rees Shapiro, “Vanished Glory of an All-Black High School,” Washington Post, January 19, 2014, p. B6. “The year the Supreme Court decisions came down, Dunbar sent 80 percent of its graduates to college, the highest percentage of any Washington school, white or Negro. That same year it had the highest percentage attending college on scholarship: one in four.” Alison Stewart, First Class: The Legacy of Dunbar, America’s First Black Public High School (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2013), p. 173.

69 Henry S. Robinson, “The M Street High School, 1891–1916,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., Vol. LI (1984), p. 122; Report of the Board of Trustees of Public Schools of the District of Columbia to the Commissioners of the District of Columbia: 1898–99 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1900), pp. 7, 11.

70 Mary Gibson Hundley, The Dunbar Story: 1870–1955 (New York: Vantage Press, 1965), p. 75.

71 Ibid., p. 78. Mary Church Terrell, “History of the High School for Negroes in Washington,” Journal of Negro History, Vol. 2, No. 3 (July 1917), p. 262.

72 Louise Daniel Hutchison, Anna J. Cooper: A Voice from the South (Washington: The Smithsonian Institution Press, 1981), p. 62; Jervis Anderson, “A Very Special Monument,” The New Yorker, March 20, 1978, p. 100; Alison Stewart, First Class, p. 99; “The Talented Black Scholars Whom No White University Would Hire,” Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, No. 58 (Winter 2007/2008), p. 81.

73 Tucker Carlson, “From Ivy League to NBA,” Policy Review, Spring 1993, p. 36.

74 See “Success Academy: #1 in New York,” downloaded from the website of Success Academy Charter Schools: http://www.successacademies.org/app/uploads/2017/08/sa_1_in_new_york.pdf. See also “New York Attacks Success,” Wall Street Journal, August 23, 2017, p. A14; Katie Taylor, “Struggling City Schools Improve Their Test Scores, but Not All Are Safe,” New York Times, August 23, 2017, p. A16.

75 See, for example, Alex Kotlowitz, “Where Is Everyone Going?” Chicago Tribune, March 10, 2002; Mary Mitchell, “Middle-Class Neighborhood Fighting to Keep Integrity,” Chicago Sun-Times, November 10, 2005, p. 14; Jessica Garrison and Ted Rohrlich, “A Not-So-Welcome Mat,” Los Angeles Times, June 17, 2007, p. A1; Paul Elias, “Influx of Black Renters Raises Tension in Bay Area,” The Associated Press, December 31, 2008; Mick Dumke, “Unease in Chatham, But Who’s at Fault?” New York Times, April 29, 2011, p. A23; James Bovard, “Raising Hell in Subsidized Housing,” Wall Street Journal, August 18, 2011, p. A15; Frank Main, “Crime Felt from CHA Relocations,” Chicago Sun-Times, April 5, 2012, p. 18.

76 Alex Kotlowitz, “Where Is Everyone Going?” Chicago Tribune, March 10, 2002.

77 Mary Mitchell, “Middle-Class Neighborhood Fighting to Keep Integrity,” Chicago Sun-Times, November 10, 2005, p. 14.

78 Mick Dumke, “Unease in Chatham, But Who’s at Fault?” New York Times, April 29, 2011, p. A23.

79 Gary Gilbert, “People Must Get Involved in Section 8 Reform,” Contra Costa Times, November 18, 2006, p. F4.

80 Geetha Suresh and Gennaro F. Vito, “Homicide Patterns and Public Housing: The Case of Louisville, KY (1989–2007), Homicide Studies, Vol. 13, No. 4 (November 2009), pp. 411–433.

81 Alex Kotlowitz, “Where Is Everyone Going?” Chicago Tribune, March 10, 2002.

82 Ibid.

83 J.D. Vance, Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis (New York: HarperCollins, 2016), p. 140.

84 Ibid., p. 141.

85 Lisa Sanbonmatsu, Jeffrey R. Kling, Greg J. Duncan and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, “Neighborhoods and Academic Achievement: Results from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment,” The Journal of Human Resources, Vol. 41, No. 4 (Fall, 2006), p. 682.

86 Jens Ludwig, et al., “What Can We Learn about Neighborhood Effects from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment?” American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 114, No. 1 (July 2008), p. 148.

87 Jeffrey R. Kling, et al., “Experimental Analysis of Neighborhood Effects,” Econometrica, Vol. 75, No. 1 (January 2007), p. 99.

88 Jens Ludwig, et al., “Long-Term Neighborhood Effects on Low-Income Families: Evidence from Moving to Opportunity,” American Economic Review, Vol. 103, No. 3 (May 2013), p. 227.

89 Lawrence F. Katz, Jeffrey R. Kling, and Jeffrey B. Liebman, “Moving to Opportunity in Boston: Early Results of a Randomized Mobility Experiment,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 116, No. 2 (May 2001), p. 648.

90 Moving To Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program: Final Impacts Evaluation, Summary (Washington: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, November 2011), p. 3.

91 “HUD’s Plan to Diversify Suburbs,” Investor’s Business Daily, July 23, 2013, p. A12.

92 Ibid.

93 During the Great Depression of the 1930s, for example, the Secretary of the Treasury, Henry Morgenthau, was appalled by a program run by the Secretary of Agriculture, Henry Wallace, who was trying to get farmers to produce less, and to dispose of existing surpluses at a time when, in Morgenthau’s words, “there’s people going hungry in America, all over America.” Morgenthau’s plan to give more of the surplus to people who were hungry was vetoed by presidential advisor Harry Hopkins. According to Morgenthau’s diary: “The minute I turned my back Harry went to Wallace and said they couldn’t do it because that is admitting everything you have done is wrong.… If we feed the undernourished the surplus food stuffs, that was admitting the plan was a flop, and we’d better not do it.” Wallace in turn told Morgenthau that giving more surplus food to the hungry would be “bad politics.” Janet Poppendieck, Breadlines Knee-Deep in Wheat: Food Assistance in the Great Depression, updated and expanded (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), pp. 238, 239–240.

94 See, for example, Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence F. Katz, “The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment,” American Economic Review, Vol. 106, No. 4 (April 2016), pp. 857, 899; Lawrence F. Katz, Jeffrey R. Kling, and Jeffrey B. Liebman, “Moving to Opportunity in Boston: Early Results of a Randomized Mobility Experiment,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 116, No. 2 (May 2001), pp. 607, 611–612, 648.

95 Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Sears, Roebuck & Company, 839 F.2d 302 at 311, 360; Peter Brimelow, “Spiral of Silence,” Forbes, May 25, 1992, p. 77.

96 Paul Sperry, “Background Checks Are Racist?” Investor’s Business Daily, March 28, 2014, p. A1.

97 Harry J. Holzer, Steven Raphael, and Michael A. Stoll, “Perceived Criminality, Criminal Background Checks, and the Racial Hiring Practices of Employers,” Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 49, No. 2 (October 2006), pp. 451–480.

98 Jason L. Riley, “Jobless Blacks Should Cheer Background Checks,” Wall Street Journal, August 23, 2013, p. A11; Paul Sperry, “Background Checks Are Racist?” Investor’s Business Daily, March 28, 2014, p. A1.

99 Douglas P. Woodward, “Locational Determinants of Japanese Manufacturing Start-ups in the United States,” Southern Economic Journal, Vol. 58, Issue 3 (January 1992), pp. 700, 706; Robert E. Cole and Donald R. Deskins, Jr., “Racial Factors in Site Location and Employment Patterns of Japanese Auto Firms in America,” California Management Review, Fall 1988, pp. 17–18.

100 Philip S. Foner, “The Rise of the Black Industrial Working Class, 1915–1918,” African Americans in the U.S. Economy, edited by Cecilia A. Conrad, et al (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2005), pp. 38–43; Leo Alilunas, “Statutory Means of Impeding Emigration of the Negro,” Journal of Negro History, Vol. 22, No. 2 (April 1937), pp. 148–162; Carole Marks, “Lines of Communication, Recruitment Mechanisms, and the Great Migration of 1916–1918,” Social Problems, Vol. 31, No. 1 (October 1983), pp. 73–83; Theodore Kornweibel, Jr., Railroads in the African American Experience: A Photographic Journey (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010), pp. 174–180; Peter Gottlieb, Making Their Own Way: Southern Blacks’ Migration to Pittsburgh, 1916–1930 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987), pp. 55–59; Sean Dennis Cashman, America in the Twenties and Thirties: The Olympian Age of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (New York: New York University Press, 1989), p. 267.

101 August Meier and Elliott Rudwick, Black Detroit and the Rise of the UAW (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), pp. 9–11; Milton C. Sernett, Bound for the Promised Land: African American Religion and the Great Migration (Durham: Duke University Press, 1997), pp. 148–149.

Chapter 4: THE WORLD OF NUMBERS

Mark Twain, Mark Twain’s Autobiography (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1924), Volume I, p. 246.

1 United States Commission on Civil Rights, Civil Rights and the Mortgage Crisis (Washington: U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, 2009), p. 53.

2 Ibid. See also page 61; Robert B. Avery and Glenn B. Canner, “New Information Reported under HMDA and Its Application in Fair Lending Enforcement,” Federal Reserve Bulletin, Summer 2005, p. 379; Wilhelmina A. Leigh and Danielle Huff, “African Americans and Homeownership: The Subprime Lending Experience, 1995 to 2007,” Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, November 2007, p. 5.

3 Jim Wooten, “Answers to Credit Woes are Not in Black and White,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, November 6, 2007, p. 12A.

4 Harold A. Black, M. Cary Collins and Ken B. Cyree, “Do Black-Owned Banks Discriminate Against Black Borrowers?” Journal of Financial Services Research, Vol. 11, Issue 1–2 (February 1997), pp. 189–204. Here, as elsewhere, it should not be assumed that two unexamined samples are equal in the relevant variables. In this case, there is no reason to assume that those blacks who applied to black banks were the same as those blacks who applied to white banks.

5 Robert Rector and Rea S. Hederman, “Two Americas: One Rich, One Poor? Understanding Income Inequality in the United States,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder, No. 1791 (August 24, 2004), pp. 7, 8.

6 The number of people in the various quintiles in 2015 was computed by multiplying the number of “consumer units” in each quintile by the average number of people per consumer unit. See Table 1 in Veri Crain and Taylor J. Wilson, “Use with Caution: Interpreting Consumer Expenditure Income Group Data,” Beyond the Numbers (Washington: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, May 2017), p. 3.

7 Ibid.

8 U.S. Census Bureau, “Table HINC–05. Percent Distribution of Households, by Selected Characteristics within Income Quintile and Top 5 Percent in 2016,” from the Current Population Survey, downloaded on July 11, 2018: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/cps-hinc/hinc-05.html

9 Herman P. Miller, Income Distribution in the United States (Washington: U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, 1966), p. 7.

10 Rose M. Kreider and Diana B. Elliott, “America’s Family and Living Arrangements: 2007,” Current Population Reports, P20–561 (Washington: U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2009), p. 5.

11 W. Michael Cox and Richard Alm, “By Our Own Bootstraps: Economic Opportunity & the Dynamics of Income Distribution,” Annual Report, 1995, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, p. 8.

12 Richard V. Reeves, “Stop Pretending You’re Not Rich,” New York Times, June 11, 2017, Sunday Review section, p. 5.

13 Mark Robert Rank, Thomas A. Hirschl and Kirk A. Foster, Chasing the American Dream: Understanding What Shapes Our Fortunes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 105.

14 U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Income Mobility in the U.S. from 1996 to 2005,” November 13, 2007, pp. 2, 4, 7.

15 Peter Saunders, Poor Statistics: Getting the Facts Right About Poverty in Australia (St. Leonards, Australia: Centre for Independent Studies, 2002), pp. 1–12; David Green, Poverty and Benefit Dependency (Wellington: New Zealand Business Roundtable, 2001), pp. 32, 33; Jason Clemens and Joel Emes, “Time Reveals the Truth about Low Income,” Fraser Forum, September 2001, The Fraser Institute in Vancouver, Canada, pp. 24–26; Niels Veldhuis, et al., “The ‘Poor’ Are Getting Richer,” Fraser Forum, January/February 2013, p. 25.

16 U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Income Mobility in the U.S. from 1996 to 2005,” November 13, 2007, p. 4.

17 Danny Dorling, “Inequality in Advanced Economies,” The New Oxford Handbook of Economic Geography, edited by Gordon L. Clark, et al (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), p. 41.

18 Thomas A. Hirschl and Mark R. Rank, “The Life Course Dynamics of Affluence,” PLoS ONE, January 28, 2015, p. 1.

19 U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Income Mobility in the U.S. from 1996 to 2005,” November 13, 2007, pp. 2, 4; Internal Revenue Service, “The 400 Individual Income Tax Returns Reporting the Highest Adjusted Gross Incomes Each Year, 1992–2000,” Statistics of Income Bulletin, Spring 2003, Publication 1136 (Revised 6–03), p. 7.

20 Heather Mac Donald, Are Cops Racist? How the War Against the Police Harms Black Americans (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2003), pp. 28, 31, 32. The original report was: James E. Lange, Ph.D., et al., Speed Violation Survey of the New Jersey Turnpike: Final Report (Calverton, Maryland: Public Services Research Institute, 2001). It was submitted to the Office of the State Attorney General in Trenton, New Jersey.

21 Heather Mac Donald, Are Cops Racist?, pp. 28–34.

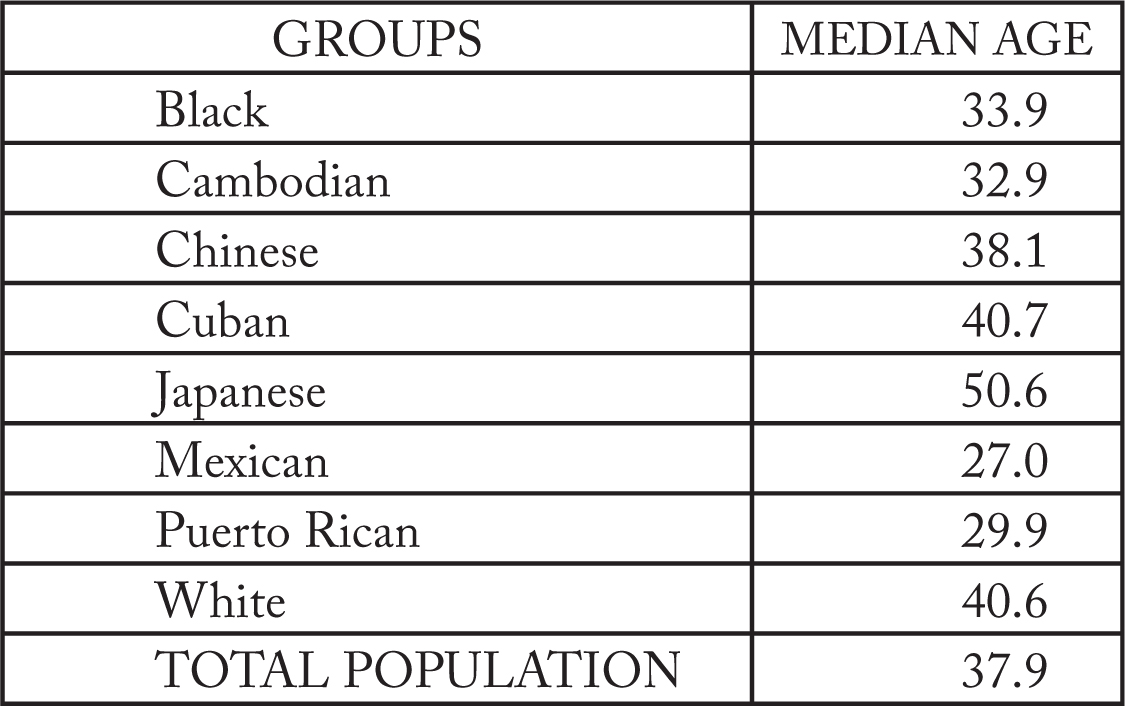

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau, S0201, Selected Population Profile in the United States, 2016 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates.

GROUPS: Black

MEDIAN AGE: 33.9

GROUPS: Cambodian

MEDIAN AGE: 32.9

GROUPS: Chinese

MEDIAN AGE: 38.1

GROUPS: Cuban

MEDIAN AGE: 40.7

GROUPS: Japanese

MEDIAN AGE: 50.6

GROUPS: Mexican

MEDIAN AGE: 27.0

GROUPS: Puerto Rican

MEDIAN AGE: 29.9

GROUPS: White

MEDIAN AGE: 40.6

GROUPS: TOTAL POPULATION

MEDIAN AGE: 37.9

23 Heather Mac Donald, Are Cops Racist?, p. 29.

24 Heather Mac Donald, The War on Cops: How the New Attack on Law and Order Makes Everyone Less Safe (New York: Encounter Books, 2016), pp. 56–57, 69–71.

25 Sterling A. Brown, A Son’s Return: Selected Essays of Sterling A. Brown, edited by Mark A. Sanders (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1996), p. 73.

26 Mark Robert Rank, Thomas A. Hirschl and Kirk A. Foster, Chasing the American Dream, p. 97.

27 Internal Revenue Service, “The 400 Individual Income Tax Returns Reporting the Highest Adjusted Gross Incomes Each Year, 1992–2000,” Statistics of Income Bulletin, Spring 2003, Publication 1136 (Revised 6–03), p. 7.

28 Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income Division, “The 400 Individual Income Tax Returns Reporting the Largest Adjusted Gross Incomes Each Year, 1992-2014,” December 2016, p. 17.

29 Devon Pendleton and Jack Witzig, “The World’s Richest People Got Poorer This Year,” Bloomberg.com, December 28, 2015; Devon Pendleton and Jack Witzig, “World’s Wealthiest Saw Red Ink,” Montreal Gazette, January 2, 2016, p. B8.

30 “Billionaires,” Forbes, March 21, 2016, p. 10.

31 With nine people who are transients in the higher bracket for just one year out of a decade, that means that 90 transients will be in that bracket during that decade. The one person who is in that higher income bracket in every year of the decade brings the total number of people in the income bracket at some point during the decade to 91. The transients’ total income for that decade, which was $12.6 million for the initial 9 transients, adds up to $126 million for all 90 transients who spent a year each in the higher bracket. When the $5 million earned by the one person who was in the higher bracket for all ten years of the decade is added, that makes $131 million for all 91 people who were in the higher bracket at some point during the course of the decade. These 91 people thus have an average annual income of $143,956.04—which is less than three times the average annual income of the 10 people who earned $50,000 a year.

32 See data and documentation in Thomas Sowell, Wealth, Poverty and Politics, revised and enlarged edition (New York: Basic Books, 2016), pp. 321–322.

33 William Julius Wilson, When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996), p. xix.

34 Ibid., p. 67.

35 Ibid., p. 140.

36 Ibid., pp. 178, 179.

37 David Caplovitz, The Poor Pay More: Consumer Practices of Low-Income Families (New York: The Free Press, 1967), pp. 94–95.

38 John U. Ogbu, Black American Students in an Affluent Suburb: A Study of Academic Disengagement (Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2003), pp. 15, 17, 21, 28, 240.

39 Thomas D. Snyder, Cristobal de Brey and Sally A. Dillow, Digest of Education Statistics: 2015, 51st edition (Washington: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2016), pp. 328, 329. See also Valerie A. Ramey, “Is There a Tiger Mother Effect? Time Use Across Ethnic Groups,” Economics in Action, Issue 4 (May 3, 2011).

40 Richard Lynn, The Global Bell Curve: Race, IQ, and Inequality Worldwide (Augusta, Georgia: Washington Summit Publishers, 2008), p. 51.

41 James Bartholomew, The Welfare of Nations (Washington: The Cato Institute, 2016), pp. 104–106; PISA 2015: Results in Focus (Paris: OECD, 2018), p. 5.

42 Robert A. Margo, “Race, Educational Attainment, and the 1940 Census,” Journal of Economic History, Vol. 46, No. 1 (March 1986), pp. 196–197.

43 Ibid., p. 197.

44 Abigail Thernstrom and Stephen Thernstrom, No Excuses: Closing the Racial Gap in Learning (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004), p. 13.

45 Stephan Thernstrom and Abigail Thernstrom, America in Black and White: One Nation, Indivisible (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997), p. 446; Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles Murray, The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (New York: The Free Press, 1994), pp. 321–323; William R. Johnson and Derek Neal, “Basic Skills and the Black-White Earnings Gap,” The Black-White Test Score Gap, edited by Christopher Jencks and Meredith Phillips (Washington: Brookings Institution Press, 1998), pp. 480–497. Similar results have been found where the data permit qualitative comparisons of other factors. See, for example, Richard B. Freeman, Black Elite: The New Market for Highly Educated Black Americans (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1976), pp. 207, 209.

46 See, for example, Richard B. Freeman, Black Elite, pp. 206–207; Thomas Sowell, Education: Assumptions Versus History (Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 1986), pp. 82–89.

47 See data in Thomas Sowell, Education, pp. 83–88. See also Richard B. Freeman, Black Elite, pp. 208–209.

48 Thomas Sowell, Education, p. 96.

49 U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Characteristics of Minimum Wage Workers: 2017 (Washington: Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2018), p. 1 and tables 1 and 7.

50 Michael A. Fletcher and Jonathan Weisman, “Bush Supports Democrats’ Minimum Wage Hike Plan,” Washington Post, December 21, 2006, p. A14.

51 “Labours Lost,” The Economist, July 15, 2000, pp. 64–65; Robert W. Van Giezen, “Occupational Wages in the Fast-Food Restaurant Industry,” Monthly Labor Review, August 1994, pp. 24–30.

52 Professor William Julius Wilson is one of those who have done this, in various books of his: The Declining Significance of Race: Blacks and Changing American Institutions, third edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), pp. 16, 95, 165; The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy, second edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), p. 177; When Work Disappears, p. 25.

53 “Labours Lost,” The Economist, July 15, 2000, pp. 64–65.

54 Richard A. Lester, “Shortcomings of Marginal Analysis for Wage-Employment Problems,” American Economic Review, Vol. 36, No. 1 (March 1946), pp. 63–82.

55 David Card and Alan B. Krueger, “Minimum Wages and Employment: A Case Study of the Fast-Food Industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania,” American Economic Review, Vol. 84, No. 4 (September 1994), pp. 772–793; David Card and Alan B. Krueger, Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995); Douglas K. Adie, Book Review, “Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage,” Cato Journal, Vol. 15, No. 1 (Spring/Summer 1995), pp. 137–140; Bill Resnick, “Studies Refute Argument Wage Increase Costs Jobs,” The Oregonian (Portland), August 25, 1995, p. B7.

56 Richard B. Berman, “Dog Bites Man: Minimum Wage Hikes Still Hurt,” Wall Street Journal, March 29, 1995, p. A12; “Testimony of Richard B. Berman,” Evidence Against a Higher Minimum Wage, Hearing Before the Joint Economic Committee, Congress of the United States, One Hundred Fourth Congress, first session, April 5, 1995, Part II, pp. 12–13; Gary S. Becker, “It’s Simple: Hike the Minimum Wage, and You Put People Out of Work,” BusinessWeek, March 6, 1995, p. 22; Paul Craig Roberts, “A Minimum-Wage Study with Minimum Credibility,” BusinessWeek, April 24, 1995, p. 22; David Neumark and William L. Wascher, Minimum Wages (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2008), pp. 63–65, 71–78.

57 Professor George J. Stigler, in a critique of Professor Lester’s survey research, not long after World War II, pointed out that “by parallel logic it can be shown by a current inquiry of health of veterans in 1940 and 1946 that no soldier was fatally wounded.” George J. Stigler, “Professor Lester and the Marginalists,” American Economic Review, Vol. 37, No. 1 (March 1947), p. 157.

58 Dara Lee Luca and Michael Luca, “Survival of the Fittest: The Impact of the Minimum Wage on Firm Exit,” Harvard Business School, Working Paper 17–088, April 2017, pp. 1, 2, 3, 10.

59 Don Watkins and Yaron Brook, Equal Is Unfair: America’s Misguided Fight Against Income Inequality (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2016), p. 125.

60 Ekaterina Jardim, et al., “Minimum Wage Increases, Wages, and Low-Wage Employment: Evidence from Seattle,” Working Paper Number 23532, “Abstract” (Cambridge, Massachusetts: National Bureau of Economic Research, June 2017).

61 “Economic and Financial Indicators,” The Economist, March 15, 2003, p. 100.

62 “Economic and Financial Indicators,” The Economist, March 2, 2013, p. 88.

63 “Economic and Financial Indicators,” The Economist, September 7, 2013, p. 92.

64 “Hong Kong’s Jobless Rate Falls,” Wall Street Journal, January 16, 1991, p. C16.

65 U. S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1975), Part 1, p. 126.

66 Steven Pinker, Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (New York: Viking, 2018), p. 99.

67 Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2014), p. 252.

68 Thomas A. Hirschl and Mark R. Rank, “The Life Course Dynamics of Affluence,” PLoS ONE, January 28, 2015, p. 5.

69 Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, p. 278.

70 Robert Arnott, William Bernstein, and Lillian Wu, “The Myth of Dynastic Wealth: The Rich Get Poorer,” Cato Journal, Fall 2015, p. 461.

71 “Spare a Dime,” a special report on the rich, The Economist, April 4, 2009, p. 4.

72 See, for example, Phil Gramm and John F. Early, “The Myth of American Inequality,” Wall Street Journal, August 10, 2018, p. A15. See also Thomas Sowell, Basic Economics: A Common Sense Guide to the Economy, fifth edition (New York: Basic Books, 2015), pp. 426–427, 428.

73 Gene Smiley and Richard Keehn, “Federal Personal Income Tax Policy in the 1920s,” Journal of Economic History, Vol. 55, No. 2 (June 1995), p. 286; Benjamin G. Rader, “Federal Taxation in the 1920s,” The Historian, Vol. 33, No. 3 (May 1971), p. 432; Burton W. Fulsom, Jr., The Myth of the Robber Barons: A New Look at the Rise of Big Business in America, sixth edition (Herndon, Virginia: Young America’s Foundation, 2010), pp. 108, 115, 116.

74 Burton W. Fulsom, Jr., The Myth of the Robber Barons, sixth edition, p. 109.

75 Andrew W. Mellon, Taxation: The People’s Business (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1924), p. 170.

76 Gene Smiley and Richard Keehn, “Federal Personal Income Tax Policy in the 1920s,” Journal of Economic History, Vol. 55, No. 2 (June 1995), p. 289.

77 Burton W. Fulsom, Jr., The Myth of the Robber Barons, sixth edition, p. 116. The share of income tax revenues paid by people with incomes up to $50,000 a year fell, and the share of income tax revenues paid by people with incomes of $100,000 and up increased. At the extremes, taxpayers in the lowest income bracket paid 13 percent of all income tax revenues in 1921, but less than half of one percent of all income taxes in 1929, while taxpayers with incomes of a million dollars a year and up saw their share of income taxes paid rise from less than 5 percent to just over 19 percent. Gene Smiley and Richard Keehn, “Federal Personal Income Tax Policy in the 1920s,” Journal of Economic History, Vol. 55, No. 2 (June 1995), p. 295; Benjamin G. Rader, “Federal Taxation in the 1920s,” The Historian, Vol. 33, No. 3 (May 1971), pp. 432–434.

78 Alan Reynolds, “Why 70% Tax Rates Won’t Work,” Wall Street Journal, June 16, 2011, p. A19; Stephen Moore, “Real Tax Cuts Have Curves,” Wall Street Journal, June 13, 2005, p. A13. Professor Joseph E. Stiglitz argued that the tax rate cuts during the Reagan administration failed: “In fact, Reagan had promised that the incentive effects of his tax cuts would be so powerful that tax revenues would increase. And yet, the only thing that increased was the deficit.” Joseph E. Stiglitz, The Price of Inequality (New York: W.W. Norton, 2012), p. 89. However, the tax revenues collected by the federal government during every year of the Reagan administration exceeded the tax revenues collected in any previous administration in the history of the country. Economic Report of the President: 2018 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 2018), p. 552; U. S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States, Part 2, pp. 1104–1105. The deficit reflected the fact that there is no amount of money that Congress cannot outspend.

79 Edmund L. Andrews, “Surprising Jump in Tax Revenues Curbs U.S. Deficit,” New York Times, July 9, 2006, p. A1.

80 James Gwartney and Richard Stroup, “Tax Cuts: Who Shoulders the Burden?” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Economic Review, March 1982, pp. 19–27; Benjamin G. Rader, “Federal Taxation in the 1920s: A Re-examination,” Historian, Vol. 33, No. 3, p. 432; Burton W. Folsom, Jr., The Myth of the Robber Barons, sixth edition, p. 116; Robert L. Bartley, The Seven Fat Years: And How to Do It Again (New York: The Free Press, 1992), pp. 71–74; Alan Reynolds, “Why 70% Tax Rates Won’t Work,” Wall Street Journal, June 16, 2011, p. A19; Stephen Moore, “Real Tax Cuts Have Curves,” Wall Street Journal, June 13, 2005, p. A13; Economic Report of the President: 2017 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 2017), p. 586. See also United States Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income 1920–1929 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1922–1932).

81 Alan S. Blinder, “Why Now Is the Wrong Time to Increase the Deficit,” Wall Street Journal, January 31, 2018, p. A15.

82 The national debt, which was a little over $24 billion in 1920—the last year of President Woodrow Wilson’s administration—was reduced to less than $18 billion in 1928, the last year of President Calvin Coolidge’s administration. U. S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States, Part 2, p. 1104. See also David Greenberg, Calvin Coolidge (New York: Times Books, 2006), p. 67.

83 David Greenberg, Calvin Coolidge, p. 72.

Chapter 5: THE WORLD OF WORDS

Epigraph