OTTOMAN ISTANBUL

Although this study focuses on the Arabic sources, another interesting perspective on women’s mosque attendance before the twentieth century is provided by European travelers’ accounts. In the foregoing sections, we have encountered the occasional testimony of a Western traveler. Starting in the fifteenth century CE and expanding significantly in the sixteenth, there is a relative wealth of reports issuing from Western sojourners in the Muslim Middle East. Many of them address a geographical area not otherwise covered here, Istanbul and Turkey. The prevalence of the Ḥanafī legal school in this region (and its institutionalization by the Ottoman state) makes it a useful component of our examination of the relationship between social practice and the normative doctrines of the madhāhib.

Because of the unique questions raised by the interpretive bias and factual accuracy of such outsider sources, this section will begin with an analysis of the changing polemical valence of European travelers’ depiction of women’s presence in (or exclusion from) mosques over the centuries. Despite the problematic nature of these “outsider” sources, however, in other ways they provide a useful point of comparison for the quite different biases and agendas of the “insider” sources used in the rest of the study. They are certainly not more accurate (and indeed they are sometimes blatantly distorted or simply ill-informed), but the addition of an alternative perspective helps us to triangulate somewhat closer to the patterns of women’s mosque usage before the twentieth century.

Although (as discussed in the introduction) the Ottoman archives are unlikely to yield comprehensive data on women’s mosque attendance for the simple reason that women’s routine presence in mosques would rarely have generated documentation in the first place, Ottoman Turkish sources of many genres will certainly contribute a much more complete picture of women’s activities than is reconstructed here. This particular sampling of sources provides only a fragmentary and provisional picture of women’s usage of mosques in Ottoman Istanbul, but it should suffice to suggest broad patterns that can usefully be contrasted with the other locations and periods surveyed in this book.

The purported exclusion of women from mosques (or their physical separation from men while worshipping there) was a trope of orientalist literature, although its content and significance shifted over time. Particularly in earlier writings, the segregation of women was regarded not as a negative peculiarity of Muslims or of “Eastern” peoples, but as a manifestation of pious propriety that might well be emulated by Christians. (It is also notable that these sources refer to the separation of the sexes, not to the exclusion of women from mosques.) Ramon Lull, a Spaniard who was granted royal permission to preach to captive audiences in mosques and synagogues in 1299, makes one of his alter egos in an imaginary theological dialogue argue that men and women should be segregated in church as they were in “the temples of the Saracens and the Jews.”259 In the early fourteenth century, the Italian jurist Giovanni d’Andrea similarly “remarked … with favor” on the separation of men and women in mosques.260 In the fifteenth century, Félix Fabri (whose admiration for the separation of the sexes in mosques we have already encountered) described the Egyptian women’s practice of praying in a separate and secluded part of the mosque, “all frivolous and worldly elegance left at home,” as being in conformity with biblical commandments.261

A European traveler before the sixteenth century would have been unlikely to find gender segregation and veiling completely alien, nor would they have appeared as distinctive attributes of “oriental” societies. The gendering of public space in some regions of contemporary Europe shared some features with that in the Ottoman Empire. Elite or young women sometimes avoided excessive exposure in public spaces, and in some locales (for instance, Venice) complete veiling was the norm.262 The gendering of sacred space was different in Europe; for instance, in conservative Venice the churches were among the few public places congenial to women.263 However, neither the segregation of the sexes for worship and preaching nor concerns about the visibility of women were completely unfamiliar to European Christians of this period (although physical and visual separation may have been less stringent than in mosques). Margaret Aston notes that “from long before the Reformation until long after,” depictions of Christian sermons show men and women in separate groups, and “the prevailing view of church pundits was that men and women could not be trusted to behave at worship and must be kept apart.”264 Noting the gender segregation of mosques in Istanbul in 1610–11, the Scottish traveler William Lithgow observes that he has encountered a similar separation among Protestants in southern and eastern Europe, “and truly me thought it was a very modest and necessary observation.”265

By the zenith of Ottoman power in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, however, the sex segregation of mosques elicited more categorically negative reflections from many European visitors to Istanbul. Although the segregation of the sexes continued to prevail in many English as well as European churches after the Reformation,266 expressions of empathy or admiration for the propriety of Muslim worship arrangements were soon outnumbered by sentiments of disapproval for supposed Muslim misogyny. The idea that women were completely excluded from mosques became commonplace and was conventionally paired with the baseless contention that Islam assigned women no place in paradise.267 This durable, if easily disprovable, trope seems to have been based on an assumed parallelism between the sacred space of the mosque and the heavenly realm, with women believed to be equally banished from both. This idea is expressed by the French travelers Philippe Du Fresne-Canaye (1573) and Pierre Lescalopier (1574).268 Stephan Gerlach, who served as the Lutheran chaplain to the Viennese embassy in Istanbul in the 1570s, reports that “the wives of Turks do not come into any mosque, because women are believed to enter into a different [part of] paradise.”269 This opinion was also reproduced by Salomon Schweigger, who served as Protestant chaplain for a Habsburg embassy to Istanbul in the same decade.270

If the trope saw its first flowering in the 1570s, it was reiterated with great regularity thereafter. It is reproduced by Jean Thévenot (who visited the Levant in the middle of the seventeenth century),271 by Germain Moüette (captured by Moroccan pirates in the late seventeenth century),272 by François Pidou de Saint-Olon (who served as French ambassador to Morocco in 1693),273 and by Aaron Hill at the beginning of the eighteenth century.274 Adrianus Reland, an early Dutch orientalist scholar, records (but then refutes with Qur’anic verses) the idea that “as the Mahometans do not suffer Women to be present at publick prayers in the Church; so neither will they be bury’d with them in the same Grave, which is without doubt founded upon this, that they believe they shall not be with them in Paradise, because they shall get younger and fairer Damsels there.”275

The emergence of stigmatizing pseudoexplanations for women’s supposed exclusion from mosques reflects an overall chronological trend in the development of European attitudes toward Muslims in general and toward their Ottoman antagonists in particular. Mohja Kahf writes that “if European culture in the seventeenth century discovered the seraglio or harem and located the Muslim woman in it, the Enlightenment declared her unhappy there.”276 In this particular case, perceptions of oppression seem to have emerged somewhat earlier. Nevertheless, some European Christians remained ambivalent or positive about sex segregation in prayer. In the late eighteenth century, for instance, Baron de Tott writes that the separation of the sexes in Muslim worship should remind Christians that “nothing ought to be permitted which may lessen the solemnity of Adoration in the Temples consecrated to [God’s] Service.”277 Similarly William Hunter, who traveled in Turkey in 1792, wrote that “women are … excluded from the moschs, from a fear of their engrossing too much of the attention of the men, which is so frequently the case at our own churches, where a pair of fine eyes is apt to relax the fervor of devotion, and to render us totally forgetful of the moral lessons of the preacher.”278

The idea that Islamic doctrine denied that women can enter Paradise was a misconception (or a slander) that proved to be remarkably resistant to factual challenge.279 George Sale labeled the assertion that Islam denies women an afterlife a “vulgar imputation,” and Pierre Bayle also refuted it in the first half of the eighteenth century.280 Nevertheless, it maintained a tenacious hold on the European imagination, as did the idea that women never entered mosques. As late as the 1830s, both Julia Pardoe and Horatio Southgate found it necessary to refute both beliefs in tandem, clearly believing them to remain prevalent among their readers.281 Southgate notes that women, in fact, do not attend congregational prayers due to concerns about mutual distraction, but also notes that the separation of the sexes at worship “is an Oriental, not a Muhammedan prejudice” prevailing equally among Christians and Muslims.282

Although Southgate denies that the separation of the sexes is specifically Islamic, it is now labeled as “Oriental.” Presumably this was possible in part because gender segregation in places of worship was no longer prevalent among Western Christians in his time, although the final victory of the “family pew” (where men and women sat together) was still relatively recent.283 In Southgate’s American homeland, by the early nineteenth century the segregation of women in synagogues “violated the gender norms associated with bourgeois American Protestant religious practice.” In the view of Christian observers, by this time the spatial separation of Jewish women in American synagogues “highlighted disreputable behavior among women and concretized male domination and female marginality” and was labeled as “Asiatic.”284 Thus, ideals of gender separation that had once seemed familiar (and praiseworthy) to Western Christians were gradually repudiated and exoticized. Southgate’s framing of gender segregation in mosques as “Oriental” also reflected the underlying dichotomy of East and West that had become the structuring convention of European travel writing.

As orientalist attitudes hardened in the context of colonial administration, women’s putative exclusion from mosques was overtly cited as a symptomatic instance of “eastern despotism.” Colonel Sir John Malcolm, who represented the British administration of India at the Persian court at the beginning of the nineteenth century, writes that “women are not allowed to join in the public prayers at the mosques” and observes that “this practice … is calculated to confirm that inferiority and seclusion to which the female sex are doomed by the laws of Mahomed.”285 In the context of Malcolm’s book, women’s lack of access to mosques is explicitly interpreted as a sign of subordination, and the subordination of women in turn is explicitly interpreted as a sign of the inability of Muslim peoples to lead themselves into freedom and progress.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, international travel became accessible to increasing numbers of Europeans. Missionaries and tourists, officials and governesses produced travel narratives and memoirs of the Middle East for an eager reading public, and a recognizable repertoire of tropes emerged within the genre. Unsurprisingly, both religious practice and the lives of women played prominent roles in these tropes. The mosques visited by European and American travelers evoked deep and conflicted emotions, ranging from reverence and longing to condescension and theological critique. Travelers were often sincerely moved by the serenity of mosque space and its accessibility to people from all walks of life who rested in its shelter or busied themselves with their own pursuits without hierarchy or exclusion.286 However, the presence or absence of women was often grounds for disparaging comment. Florence Nightingale, writing of the mosques of Cairo in 1850, combined both themes when she observed:

Here is silence, here is space, here is room for thought in these vast colonnades; turn in here, walk up and down among those columns, no one will disturb you but those prostrate men, with their faces to the ground, as silent as yourself. Are you tired of your daily work and the busy city? Here are places where everyone may have rest and thought. … Oh! if the poor women had but been there, I could have said, this is the very thing I have often sighed for in London.287

Nightingale’s experience of Egyptian mosques was very much shaped by her country’s increasing power, which ensured her access to these spaces through means that even she found disturbing. “The great drawback is that, as you must have a firman and a Pacha’s janissary, and pistols, and whips, and I don’t know what besides, to visit them.”288 Consequently, her grasp of the normal usage of an Egyptian mosque must have been very limited. It seems likely that the Alexandrian mosque she visited had “a gallery out of sight, where women are allowed,” but she is presumably relying on hearsay in stating that it was accessible “only on the evenings of the feasts, and only [to] old women.”289

With the rise of organized tourism and the proliferation of religious missions in the Middle East in the nineteenth century, European and American women began to produce accounts of travel and residence in the region that often reflected greater direct access to Muslim women and, in some cases, greater empathy toward them.290 Pardoe, who had an extended stay in Istanbul in 1835–36, wrote a work that has been described as “the most detailed, most sympathetic description of the Turkish élite before the Tanzimat, or reform era.”291 We have already encountered in the introduction her description of the routine presence of women in Istanbul mosques and of the dissonance between this fact and the preconceptions of European visitors.

Even for female observers, however, women’s access to mosques and other holy places was often taken as an index of Muslim attitudes toward gender (and, implicitly, of the validity of Islam and the moral level of Muslim polities). Sarah Barclay Johnson (who spent three years in Jerusalem) writes in the 1850s of the Dome of the Rock that it is “an unusual thing for females (who, in Mohammedan estimation, are no better than brutes) to pollute with their presence so holy a place”292; of al-Aqṣā, she remarks disapprovingly, “I noticed that the worshipping-place of the men was covered with carpeting, while that of the women was spread with tattered matting!” Once again, women’s accommodation in mosque space was taken as an index of their standing in Muslim society. In contrast, Johnson does not assign any symbolic significance to the fact that her own access to at least one holy site in the Ḥaram (the Temple Mount) was impeded by crowds of women.293

Western perceptions of women’s exclusion from mosques—and the persistently associated belief that Islam denied women’s possession of souls—eventually became a factor in some Muslim thinkers’ perceptions of their own religious predicament. Muḥammad ʿAbduh lamented that ill-informed Europeans “accuse us of barbarism in the treatment of women” and attribute the perceived mistreatment to Islam.

A European tourist visited me at al-Azhar, and while we were passing through the mosque the European saw a girl passing through it. He was astonished and said, “What is that? A female entering the mosque!” I said to him, “What is unusual about that?” He said, “We believe that Islam posits that women do not have souls, and are not obligated to pray!” I cleared up his mistake for him and explained some of the Qurʾanic verses about [women] for him.294

In light of this history, Western travelers’ reports about women’s mosque access must be handled with care. Nevertheless, when used with caution, they offer potentially helpful outsider glimpses of practice.

One of the earliest observations about women’s mosque attendance in the Ottoman Empire is by a Bavarian, Johann Schiltberger, who was taken prisoner at the Battle of Nicopolis and spent the years from 1396 to 1402 in the service of Sultan Bayezid. He reports that “they do not allow any woman in the temple, so long as they are inside.”295 Although brief and vague, this report interestingly suggests that women are excluded from the mosque specifically at the times of congregational prayer. Konstantin Mihailović, a Serbian who was captured by the Turks in 1455 and served in the Janissary corps, is more categorical in his brief denial that women go to mosques; he states that the Turks “admit no woman to the temple, nor do they go.”296

The claim that women did not go to mosques (at least at times of congregational prayer) is nuanced by an anonymous German who was taken captive by the Ottomans as a teenager in the 1430s. Over the course of his twenty years in Turkey, he claimed to have mastered Turkish, feigned conversion to Islam, and even pursued some degree of Muslim religious learning.297 In his memoir, he strongly emphasizes the veiling and seclusion of Turkish women, practices that he depicts in a positive light and compares favorably with the demeanor of Christian women (presumably those at home in Germany). In the “churches [i.e., mosques],” he reports, “they have an enclosed place separated from the men, so that no one can see them or go in to them.” Furthermore, not all women can go to the mosque, nor do they frequent it often; only “noble” women can go for a time on Friday afternoon to pray. Otherwise, they are not allowed to go because it is considered unseemly.298 This information (that only high-status women can go to mosques, but do so seldom, and that women have an enclosed section separate from the men) also appears in the account of Leonhart Rauwolff in the sixteenth century, but the parallel is sufficiently close that it may be dependent on this earlier source.299

Another account of Ottoman Turkish women’s access to mosques was offered in the mid-sixteenth century by Bartholomej Georgijevic, a Croat who was taken prisoner in the Battle of Mohács (1526) and remained enslaved for thirteen years.300 He reports that in mosques women never mix with the men, but have “a separate place to sit,” where they can be neither seen nor heard by the rest of the congregation. Furthermore, women very rarely go to the mosque, only “at Easter [sic]” or on Fridays. He continues in a somewhat different vein, stating that

they pray in the churches [i.e., mosques] at night from the ninth to the twelfth hour, or midnight. While praying they twist and cry out so piteously, and get into such a piteous (kläglich) state, that a few of them faint and often fall powerless onto the floor. If it so happens that one of them feels as if she were pregnant while she prays, she believes that she has conceived by the grace of the Holy Ghost; when [such women] give birth, they call the child nefes oğlu, that is, “child of the spirit or the Holy Ghost.” This I have heard from one of the female servants and not seen myself, because no man may see their prayer.

He states, however, that he has often seen men pray and gone there (presumably to the mosque) himself.301

Despite the incongruous Christian terminology, Georgijevic is clearly speaking of Muslim women; the context of his comments is a passage describing Islamic prayer. What Georgijevic means by “Easter” is unclear, but it is possible that he is referring to Ramadan because this would probably have been the most visible religious season (involving a lengthy period of fasting and a final multiday festival, something like Lent and Holy Week) and is known from later sources to be a time when women particularly frequented mosques. More surprising is Georgijevic’s account of ecstatic worship by women in the mosques at night, which sounds like a form of ṣūfī dhikr. Assuming that he is indeed referring to Ramadan, this could also be a reference to tarāwīḥ prayers. Georgijevic was an outside observer (and a man) whose report depends on hearsay. Nevertheless, it is not impossible that this report offers a tantalizing glimpse of women’s activities in sixteenth-century Ottoman mosques.

An Italian named Antonio Menavino, who claimed in his dedicatory letter to the King of France to have been a slave for many years in the household of the Ottoman sultan in the first half of the sixteenth century, provides a detailed, but confusing and somewhat suspect account of the limitations placed on women’s mosque attendance. He claims that prostitutes and “women that are not bound in marriage” may not attend mosques, but that “virgins and widows of five months, not having any use of men,” are admitted; “there in church [i.e., the mosque] they are covered and aside in such a way that the men are without sight of them so that seeing them does not conceive in their mind some evil thought whence they commit some sin.”302 It is unclear what might distinguish “virgins” from “women that are not bound in marriage,” and it seems odd for “virgins” to be identified as exempt from strictures upon women’s presence in mosques (unless he is referring to preadolescent girls). His reference to “widows of five months” is also opaque, although it does very roughly correspond to the four months and ten days of seclusion (the ʿidda) incumbent on a woman after the death of her husband. The same, somewhat garbled information appears in a work supposedly composed by a Spanish slave around the same time; it is unclear which text has priority, or how much credibility either deserves.303 In any case, it reinforces the general impression, apparently originating in actual experience of the Ottoman Empire, that limited categories of women did have access to mosques, but that they were spatially separated from the rest of the congregation and concealed from male view.

Although travelers of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries often suggested that there were social and reputational barriers to women’s attendance of mosques, they give no clear or unanimous account of the parameters of these limitations. Hans Dernschwam, who traveled to Istanbul and Asia Minor in 1553–55, states that in Turkey only disreputable women go to “church”; rather, women pray at home, having learned how to do so from their parents and husbands.304 “If some old woman wants to pray in the church, she must stay in the very back, behind all of the men. Because of the Turks’ whoring, the women cannot go to church among the men.”305 Although the mention of elderly women is unsurprising, it is striking that Dernschwam believes that only less respectable women go to the mosque, whereas the anonymous German captive represents mosque attendance as the privilege of a few “noble” women. Another European who sojourned in Istanbul in the early 1550s, the diplomat Nicolas de Nicolay, similarly states that very few women enter mosques “unless they are ladies of great authority and reputation.”306 It is difficult to know whether these inconsistencies should be attributed to the different time periods, social contexts, and locations where the authors got their information or simply to the limitations of their knowledge of local practice. In any case, although the multiple authors who offer more detailed remarks collectively refute the stereotyped claim that Turkish women simply had no access to mosques, they do reinforce the idea that women’s attendance was perceived as limited (with the possible exception of the nights of Ramadan).

Two centuries later, a more coherent account of the social pressures limiting women’s mosque attendance is offered by Ignatius Mouradgea d’Ohsson (d. 1809), an Armenian Christian life-long resident of Istanbul whose description of Ottoman life was intended for a European audience. D’Ohsson, whose perspective appears to be informed by his extensive contact with the upper reaches of Ottoman society, describes Turkish women as leaving the home rarely—and then only if accompanied by slaves and guarded by eunuchs or domestic servants. It is for this reason, he states, that only older women can go to the mosque (and most women of all social stations pray individually in their homes).307 Here the primary factor appears to be a preference for women’s seclusion, a consideration that presumably would have applied primarily to women of high social status and ample resources.

It is notable that with the exception of Dernschwam (who implies that women simply placed themselves behind the men—perhaps in smaller mosques), travelers’ reports that acknowledge women’s worshiping in mosques suggest that they were allocated spatially and visually separate spaces in which to do so. The location and nature of these spaces are not always clear. In some cases, women are implied to be outside of the mosque proper. Lescalopier, who visited Istanbul in 1574, writes that there are “porticoes, tombs (charniers) and squares” at the front of (devant) the mosques where the Turkish women can worship because they are not allowed into the mosques; although difficult to interpret, this remark may suggest that women prayed in the arcades and courtyards that preceded entry into the mosque proper.308 Writing of a visit to Istanbul in the early 1610s, Sandys states that “the women are not permitted to come into their temples (yet have they secret places to look in thorow [through] grates).”309 This might conceivably mean that women peeked into mosques from outside of the buildings, but it is more likely that he refers to women’s sections that communicated with the main mosque space through gratings. De Tott, who lived in Istanbul and learned Turkish for a number of years in the middle of the eighteenth century, remarks that “the Women, who are also admitted into the Mosques, have a particular Place alotted them.”310 Hill (who lived in Istanbul for three years starting in 1700311) states that “women are but rarely suffer’d to appear in Mosques, and then are plac’d all over Veiled, behind a large and darkn’d Lettice [lattice].”312

These descriptions (even though vague) seem to suggest that women’s sections were separated by screens, but not necessarily that they were on a separate level from the main prayer space. Because in the twentieth century balconies have become a paradigmatic form of mosque space that is often anachronistically projected into the past, it is worth pausing to examine the historical origin of the “women’s balcony.” Certainly pre-Ottoman mosque architecture did not routinely include balconies. Across the Muslim Middle East, historically one of the most common arrangements seems to have been for women to pray under the arcades that enclosed the courtyard of the mosque; we have already encountered this arrangement in Medina and in Cordoba (although, as we have seen, even here descriptions are sometimes gratuitously assumed to refer to balconies). Anselme Adorno, a European who traveled to the Holy Land in 1470–71 (visiting Tunis, Cairo, Damascus, and Beirut in the course of his trip), describes the layout of a typical mosque as follows: “Their churches [i.e., mosques] or djemmas [i.e., jāmiʿ, Friday mosque] are not made like ours. They generally have colonnades or galleries with polished columns all around, in which women are admitted. In the middle there is a great courtyard or atrium, usually as long as it is wide, also paved with polished marble.”313

There is some pre-Ottoman evidence that has been interpreted to suggest that women were located in balconies, but on closer examination it proves to be ambiguous. As we have seen, Talmon-Heller cites an anecdote from thirteenth-century Syria in which, after all the men in the village mosque eat their fill, “the food was taken up to the women (rufiʿa ilā al-nisāʾ).”314 Talmon-Heller infers from the verb “taken up” that the women “apparently sat in an upper gallery.”315 Although this is a plausible inference, the Arabic verb rufiʿa may also simply mean that the food was picked up and taken to the women (wherever the women were located).

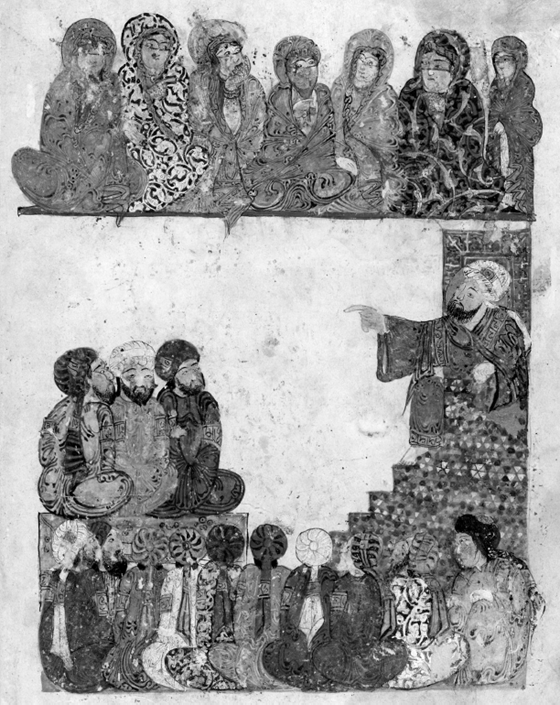

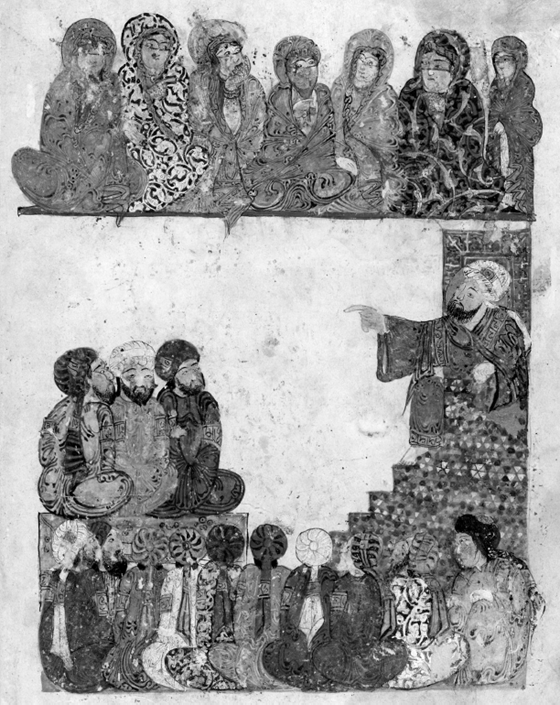

FIGURE 2.1 Women listen to a preacher in a miniature from the Maqāmāt of al-Ḥarīrī (thirteenth century).

Courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale. Paris

More striking is the visual evidence of an illustration of the Maqāmāt of al-Ḥarīrī (figure 2.1), dated 634/1237, whose exact geographical provenance is unknown.316 Here women appear in a row placed high above the men who sit at the foot of the preacher’s pulpit. However, unlike other miniatures in the same manuscript,317 this image does not provide any architectural context for the upper row of figures; the line of women floats high in the composition, without any structural elements indicating a balcony. Thus, it remains unclear whether the women are placed above the men as a literal depiction of their location in a structure on an upper level of the mosque or simply as a visual shorthand for their separation from the men.318 In contrast, another thirteenth-century illustration of the same maqāma319 unambiguously depicts an arcaded balcony on the upper level of the mosque, but due to the intentional defacement of the human figures in that manuscript, the gender of the figures located there can only be inferred. Oleg Grabar thus observes that “the upper gallery … contains (presumably female) figures behind a wooden baluster,” whereas in describing the previous miniature, he remarks that the women sit in “what is presumably a separate galleried area of the mosque” (emphases mine).320

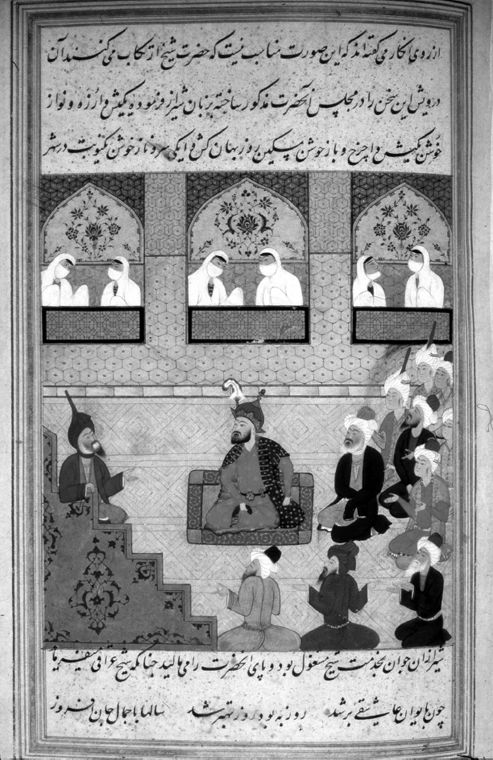

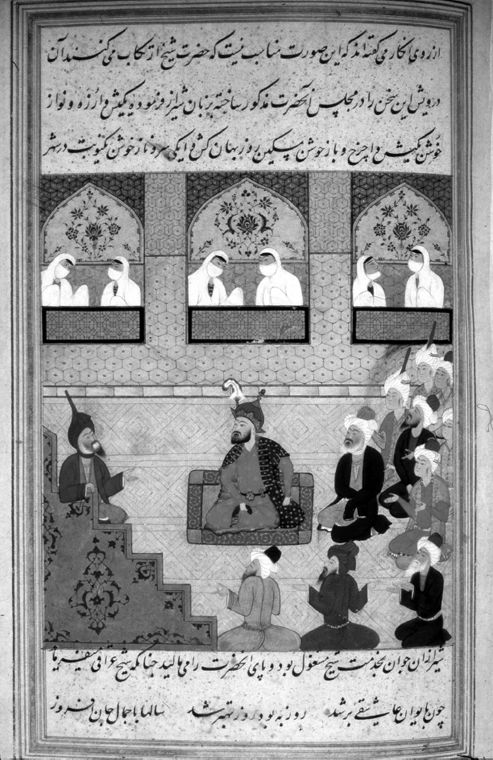

FIGURE 2.2 Women listen to a preacher in a miniature from Ḥusayn Baiqarā’s Majālis al-ʿushshāq (sixteenth century).

Courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, UK

Thus, a pervasive assumption that women are located in balconies—and that, conversely, balconies are intended for women—has informed the reading of the relevant visual evidence rather than being unambiguously dictated by that evidence. Another example is a mid-sixteenth-century Persian miniature, similarly depicting a preaching session with men gathered at the foot of the minbar and veiled women watching from what appears to be a balcony (figure 2.2).321 Wiebke Walther describes the women as “taking part in a service in a mosque from a position in a gallery of their own.”322 Although this “gallery” may well be a balcony, the artist has depicted the floor of the mosque essentially vertically; the “gallery” is certainly not an entire story above the line marking the end of the floor. In the absence of naturalistic perspective, spatial relations in such miniatures are difficult to interpret; the image may or may not depict a true women’s balcony.

The interrelationships among visual representations, physical spaces, and textual evidence are complex, and it is all too easy for ambiguous evidence in one category to support questionable readings of another, leading to a self-reinforcing—if not necessarily invalid—circle of interpretations. For instance, Sheila Blair writes of Iran in the Ilkhanid period (thirteenth to fourteenth centuries CE) that in illustrated manuscripts women are often depicted “peeking out” of upper-story windows. “The depiction of women in second stories may reflect actual practice, for this period was when second-story balconies were introduced into congregational mosques, as at Varamin and Yazd.”323 This is certainly a plausible inference. However, it is also conceivable that the placement of women in an upper register in part represents an artistic convention rather than a literal depiction of the allocation of space.324 Similarly, the existence of balconies in mosques cannot in itself serve as evidence that they were intended for the use of women.

The existence of pre-Ottoman women’s balconies thus remains unclear pending further evidence. By the Ottoman period, in contrast, it is clear not only that balconies were often present but also that they were at least sometimes used by women. An Ottoman manuscript dated 1600 unmistakably displays veiled women listening to preaching from the second-floor balcony of a mosque.325 However, it is not automatically to be assumed either that the large balconies of major Ottoman mosques were initially built with women in mind or that the women who did frequent these mosques were consistently located in the balconies.326 It is well known that, for instance, the balcony of the Byzantine church of Hagia Sophia (after the conquest in 1453 the premier mosque of Istanbul) was known as the gynaeceum, or “women’s section”; however, it is far from clear that this was the primary function of the church balcony by the time of the Ottoman conquest. It appears that by the fourteenth century the balconies were reserved for the emperor and the nobility (particularly noble women) rather than for women per se.327 Similarly, after the conquest the balconies of major Ottoman mosques often housed royal loges where members of the dynasty of both sexes could worship in seclusion.328 Describing the balconies of several major Ottoman mosques, the seventeenth-century Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi makes no reference to their use by women. Other than providing extra space on occasions that attracted a particularly large congregation, the balconies seem to have been devoted to providing an enclosed prayer space for the ruler and sometimes space for Qur’an reciters.329

However, by the eighteenth century the use of balconies as women’s prayer space is mentioned as being standard in at least some Ottoman mosques. A European description, published in the mid-eighteenth century but based on older sources, states that in mosques men pray downstairs, women “in the upper galleries or under the exterior arcades.”330 D’Ohsson states that on those occasions when women do attend the mosque, they pray in galleries elevated over the entrance to the mosque; this arrangement guarantees that they are located at the back of the congregation, as required by the sharīʿa.331 Antoine-Laurent Castellan, a French painter (d. 1838) who visited the Ottoman Empire at the turn of the nineteenth century, reports that “the women have pews [sic] enclosed with lattice-work, and situated above the doors. They are not numerous, because the law permits elderly females only to attend meetings of the other sex.”332

Nevertheless, even in a much later period it does not appear that balconies were consistently identified as women’s space or that women were confined exclusively to balconies in mosques where they were available. In the nineteenth century, Pardoe describes the balcony of Hagia Sophia as having been “devoted originally to the use of the women”; there is no sense that she perceives this as its current use.333 Interestingly, Southgate describes screened balconies as a Near Eastern Christian, rather than a Muslim, convention.334 Not all mosques necessarily offered (or required) physically separate accommodations for women even during congregational prayers; James Boulden reports in the mid-nineteenth century that “women are permitted to worship in the mosques, but are compelled to form themselves into a distinct group, somewhat remote from the men.”335 This could be true even when a balcony was present; writing about a visit to the pilgrimage mosque of Eyüp in the early twentieth century, Grace Ellison describes watching from the screened gallery originally reserved for the sultan as both men and women, separated by a partition, perform the prayer on the main floor below.336

It is clear that between the hours of formal congregational prayer, women freely frequented the main floors of major mosques. This was true even in an edifice characterized, like Hagia Sophia, by the presence of vast upper galleries. In the eighteenth century, Elizabeth Craven mentions that on a visit to Hagia Sophia “I went and sat some time up stairs, to look down into the body of the temple—I saw several Turks and women kneeling, and seemingly praying with great devotion.”337 As we have seen, in the mid-1830s Pardoe observed some women praying on the main floor.338 Late in the nineteenth century, Edmondo de Amicis similarly describes looking down from the balcony of Hagia Sophia to see “some veiled women on their knees in solitary corners” on the floor below.339

Indeed, Ottoman women seem to have preferentially frequented mosques between prayer times, to the point that from an early date some European observers believed that they visited mosques only when the men were not there. We have seen that Schiltberger implied as much. Schweigger, the German who acted as preacher for a diplomatic delegation to Istanbul in the late 1570s, writes that women do not pray at mosques but at home unless they visit the mosque simply for the sake of sightseeing (sehens haben) when no services are being held.340 Lithgow, who visited Istanbul in 1610–11, writes that in mosques “the men observe their turnes and times, and the women theirs, going alwayes when they goe, either of them alone to their devotion.”341 Southgate writes in the 1830s that “women are not … allowed to be present in the mosques at the time of public prayers,” but that “in the intervals between the public prayers, Turkish females are allowed to enter the mosques and perform their devotions, if no man is present. They are also permitted to hear the discourses of the preacher, though often of a character unfit for modest ears.”342 Writing about Bosnia in the late nineteenth century, Thomson writes that women “are not allowed to enter the mosque at the same time as the men. There are, however, certain hours allotted to them when they may go there to pray.”343

In the light of other information, it seems unlikely that women were completely barred from mosques at times of communal prayer, although they may more often have engaged in private devotions between official prayer times. There are scattered suggestions that Ottoman policy may have barred women from mosques at night, although this is also difficult to confirm. Lady Wortley Montagu, visiting the Sultan Selim Mosque in Edirne at the beginning of the eighteenth century, writes of its myriad lamps that “this must look very glorious when they are all lighted; but that being at night, no women are suffered to enter.”344 Pardoe states that entrance to mosques “is forbidden to them [i.e., women] only during the midnight [sic] prayer.”345

In the nineteenth century, the profusion of relatively well-informed accounts by European and American travelers and residents in Istanbul—and their greater access to mosques, although it remained limited—provides a composite picture of women’s usage of mosque space. At least in major mosques, women do seem to have been present during congregational worship, but apparently they attended in relatively small numbers; Lucy Garnett writes that “the few elderly women and children who may be present” are “concealed in a latticed gallery approached by a separate entrance.”346

As in other periods and geographical areas, the opportunity to hear preaching seems to have been one of the main reasons for women to visit mosques. As we have seen, Southgate identifies preaching as an activity to which women were admitted. Writing later in the nineteenth century about a visit to Hagia Sophia, Annie Jane Harvey describes watching from the balcony as the congregation performs Friday prayers. At the end of the formal service, “those who wished retired. The remainder approached nearer a small pulpit into which another Imaun [sic] mounted, who, seated cross-legged on a cushion, commenced an exposition of some portion of the Koran. No women had hitherto been present during the service, but a few now entered and seated themselves behind the men.”347

Although some women may have attended mosque preaching sessions in various contexts, a number of sources agree that they attended in particularly large numbers during the fasting month of Ramadan. The author William Makepeace Thackeray visited Istanbul during Ramadan in 1844 and describes the following scene at the Mosque of Sultan Ahmet:

Any infidels may enter the court without molestation, and, looking through the barred windows of the mosque, have a view of its airy and spacious interior. A small audience of women was collected there when I looked in, squatted on the mats, and listening to a preacher, who was walking among them, and speaking with great energy. My dragoman interpreted to me the sense of a few words of his sermon: he was warning them of the danger of gadding about to public places, and of the immorality of too much talking.348

It sounds somewhat odd for the preacher to be “walking among” the women, but the scene otherwise sounds highly plausible. It is interesting that, if Thackeray’s interpreter was to be believed, the women’s foray into public space was apparently being used to dissuade them from “gadding about in public places.” If accurate, this is another example of the paradoxical ways in which access to mosque space could be used to expose women to religious norms that potentially constrained them.

The prevalence, or even dominance, of women at some major mosques during Ramadan is also vividly described by a Turkish author, Halidé Edib, whose memoirs describe events of her childhood in the Istanbul of the 1890s. Visiting the Suleimaniye Mosque with her wet nurse on the first day of Ramadan, she describes how men chanted the Qur’an and swayed before the miḥrāb while preachers held forth from multiple pulpits on the floor of the mosque. She notes that “there were more groups of women than men around the preachers.”349 The party returns to the mosque at night for the tarāwīḥ prayers; on this occasion “the women prayed in the gallery above.”350 Here the segregation of men and women (and the location of women in the balcony) appears to be specific to the performance of congregational prayers. The fact that women in nineteenth-century Istanbul frequented mosques particularly in Ramadan is corroborated by Fanny Blunt, the wife of Britain’s consul general to Constantinople, who is credited with “one of the most reliable accounts of everyday life” in Turkey.351 In her book, published in 1878, she states that “in most mosques women are admitted to a retired part of the edifice; but it is only elderly ladies who go. In some mosques at Stamboul, where the women’s department is partitioned off, the attendance is larger, especially during Ramazan.”352

Hester Donaldson Jenkins, writing in the early twentieth century, sums up her experience with the religious practices of Turkish women as follows: “A girl has … nothing corresponding to our Sunday schools, nor does she often attend services in the mosques. … There is an occasional mosque reserved for women, and in some others, arrangements are made by which a congregation of women and girls may be accommodated behind curtains, where they may hear the chanting of the Imams, but cannot be seen by the male worshippers. I know Turkish women who have never been inside a mosque.”353 Jenkins believes that women could benefit from the “sensible, practical” sermons that men hear at the mosque and that very few women do. In contrast, she speaks with admiration of the magnificent sights that can be enjoyed by women who attend the nighttime prayers in the gallery of Hagia Sophia during Ramadan.354

Overall, the evidence suggests that women were not strictly barred from mosques, but that in most cases their presence was perceived as being minimal. There are several possible explanations for this pattern. As we have seen, D’Ohsson relates women’s relative absence from mosques to overall limitations on their mobility and visibility outside the home (a consideration that may have been particularly relevant in the elite circles that he frequented). However, other (somewhat later) observers cast doubt on this interpretation.355 Southgate recounts of the festival prayers on the Greater Bairam (ʿĪd al-Aḍḥā) in Istanbul in 1839 that “so much of the ample space of the Atmeidan as was not occupied by the worshippers, was filled with throngs of Turkish maids and matrons, on foot and in arabas [carriages], idle spectators of a ceremony of their religion in which they could not participate.”356 In this case, it was clearly not women’s seclusion within the home that prevented them from taking part. Rather, the anecdote suggests adherence to a widespread position in Ḥanafī jurisprudence that affirmed women should swell the crowds at festival prayers, but denied they should take part in the congregational prayers.357 In the later nineteenth century, the women of the royal household rode in open carriages in the procession to Friday prayers with the sultan; however, upon arrival at the mosque they remained waiting in their carriages until the congregational prayers were concluded.358 Again, the issue appears to be more one of doctrine (the undesirability of the women’s participation in mixed prayers at the mosque) than of female invisibility or seclusion. To the extent that this is the case, however, it reflects a divorce between received Ḥanafī rules and their formal rationales, which based disapproval for women’s mosque attendance largely on the undesirability of their venturing out of the home.359

Indeed, the relative absence of women appears to have applied more to the specific ritual activity of congregational prayer than to mosque space per se. Not only did women flock to major mosques during Ramadan, but also outside of organized prayer times mosque space seems to have played a role in the everyday lives of many (although certainly not all) women. As we have already seen, travelers often noted the presence of women tarrying or praying in mosques outside the times of organized worship. Edmondo de Amicis, who spent time in Istanbul in 1874, charmingly evokes the outdoor activities of local women as follows: “It is amusing to follow one of them from a distance to see how she manages to eke out and refine the pleasures of gadding about. She enters the nearest mosque to say a prayer, and then stays for a quarter of an hour under the portico chatting with a friend; then she’s off to the bazaar.”360

Indeed, nineteenth-century travelers’ accounts of Ottoman Egypt similarly suggest that, if women rarely attended congregational prayers, they nevertheless freely used major mosques at other times. Edward William Lane, who resided in Cairo for extended periods between 1825 and 1835 (and who conformed to Muslim practices in order to facilitate his integration into local society), had extensive exposure to life in Cairene mosques. He writes categorically that “in Cairo … neither females nor young boys are allowed to pray with the congregation in the mosque, or even to be present in the mosque at any time of prayer.”361 Nevertheless, outside of the formal “time of prayer” women’s presence was routinely noted. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Ulrich Seetzen describes visiting the Mosque of ʿAmr ibn al-ʿĀṣ in Cairo and encountering women who showed him the sacred sights of the edifice.362 James Augustus St. John, who also traveled in Egypt at the beginning of the 1830s, reported of the mosque of al-Azhar that “contrary to the ideas commonly prevailing in Europe, a large portion of the votaries consisted of ladies, who were walking to and fro without the slightest restraints, conversing with each other, and mingling freely among the men.”363 In a travel narrative published in 1850, the Reverend J. A. Spencer describes a visit to the mosque of Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn in Cairo: “At this hour, being about the middle of the forenoon, there were very few persons present; one old man, doubtless a mendicant, from his looks, lay stretched out at full length, asleep on the matting, not far from the pulpit: a number of children were running about, and playing very noisily; and several women seemed to be lounging around, more to gratify their curiosity than anything else.”364

A quarter century later, Charles Dudley Warner wrote of the myriad mosques of Cairo:

At all hours you will see men praying there or reading the Koran, unconscious of any observers. Women I have seen in there occasionally, but rarely, at prayer; still it is not uncommon to see a group of poor women resting in a quiet corner, perhaps sewing or talking in low voices. The outward steps and open courts are refuges for the poor, the friendless, the lazy, and the tired. Especially the old and decaying mosques, do the poor frequent. There about the fountains, the children play, and under the stately colonnades the men sleep and the women knit and sew.365

Like other writers of this period, Warner sees the mosque—particularly between times of congregational prayer—as a haven for the Muslim populace at large, and the presence of women is an integral part of the mosque’s inclusive embrace.

Whereas in Istanbul women’s mosque attendance appears to have peaked in the month of Ramadan, Lane describes women’s mass participation in the observation of a round of festivals reminiscent of those denounced by Ibn al-Ḥājj. He provides a lengthy and vivid description of the Mosque of al-Ḥusayn on the occasion of ʿĀshūrāʾ, when the mosque “was crowded with visitors, mostly women, of the middle and lower orders, with many children.”366 According to Lane, the normal etiquette of mosque visitation was suspended for this festival because the density of the throngs and the dirt they tracked into the mosque made it impossible to prostrate and pray in the normal manner.367

Overall, this sampling of evidence about women’s mosque attendance in Ottoman Istanbul (which will surely be supplemented and emended in the future by Ottoman Turkish sources) suggests that it may have been quite limited. Even largely discounting the validity of repeated outsider reports that women simply did not go, which often bear clear marks of bias and misinformation, there seems to be a clear consensus even among better-informed observers that congregational prayers were attended by very small numbers of women—and often only at an advanced age.368 Nevertheless, the patterns indicated by these sources suggest not primarily the gendering of space, but the gendering of activities. Although women’s participation in congregational prayer appears to have been very limited, there seems to have been no consistent taboo on women’s presence in mosques. If the specific occasions differed from those familiar in Egypt, it was similarly the case that women flocked to mosques on those occasions when their presence was customary, and for at least some women mosques were among the urban spaces that might be visited casually over the course of a day.

To a certain extent, this is what might have been anticipated on the basis of Ḥanafī doctrine, which (as we have seen) assigns no special value to congregational prayer by women and by the Ottoman period usually discouraged women’s participation in public worship altogether. However, on the basis of such normative texts the widespread presence of designated women’s sections could not have been anticipated; neither could the mass presence of women in major mosques during Ramadan. Both of these things suggest that practice was, again, shaped by the desires and lived practices of women, as well as by the teachings of the legal scholars. Legal doctrine appears to have substantially informed or constrained women’s behavior, but clearly did not unilaterally dictate it.

CONCLUSION

In the mid-sixteenth century CE, a Mālikī scholar whom we shall encounter in greater depth in the next chapter observed of the categorical disapproval of women’s mosque attendance expressed by many postclassical Islamic jurists, “This is an opinion that was not accompanied by practice, because in all ages the women of the Islamic domains have continued to attend mosques.”369 As we have seen, a century earlier Ibn Ḥajar al-ʿAsqalānī referred to “the continuous practice based on the permissibility of women’s going out to mosques and markets.”370 The evidence collected in this chapter, fragmentary though it may be, demonstrates the overall accuracy of these two scholars’ observations as regards the Middle East and North Africa. Legal scholars rarely actively encouraged women’s mosque attendance and often vigorously deprecated it; however, sources of many dates and genres demonstrate that women often had a significant presence in mosques in most regions of the premodern Arab Islamic world. They frequented mosques to participate in congregational prayer, to celebrate the great nocturnal festivals of the medieval Islamic calendar, to hear preaching, to teach, to socialize, and to rest.

To say that women had access to mosques, however, does not imply that they frequented mosques to the same degree, at the same times, or for the same reasons as men. To categorize mosques (or at least the great mosques of the major metropolises) as “male space” would be to ignore the fluidity of mosque space and the multiple uses to which it was put. Neither, however, were mosques used identically by men and women. The divergence between women’s and men’s practices reflects not merely women’s ignorance or defiance of the norms established by elite male scholars but also their own distinctive goals and priorities, which sometimes favored other religious venues and activities. The scholarly religious establishment could not exercise unilateral control over the behavior of the broader public, male or female, even within formal religious venues such as mosques. Nor was its agenda monolithic; ritual practices denounced by some religious scholars might be tolerated, endorsed, or even presided over by others. Few activities were exclusive to either men or women; however, their differential distribution must have yielded quite different overall patterns. For instance, although in many times and places both men and women thronged to mosques on nights like the Prophet’s birthday and Niṣf Shaʿbān, such occasions must have loomed larger in the mosque experience of those women who did not regularly attend Friday prayers.

Furthermore, the distribution of activities was not uniform across different regions, although the patterns are difficult to reconstruct with any specificity. The relative prevalence of references to designated space for women’s congregational prayer and to women’s presence at Friday prayers in Spain and North Africa suggests that this may have been a more salient activity for women in those regions than in some areas further to the east—or perhaps that there was greater attention to gender segregation, at least in the context of congregational prayer, than there was in Egypt or Syria. In contrast, the wealth of references to women’s presence at preaching sessions in Syria suggests that it may have been a predominant focus of women’s mosque activities there. The ingrained nature of such regional patterns is suggested by the shock of the North African ʿAlī ibn Maymūn when he encountered mixed preaching sessions after his move to Syria; it may also be reflected in the more frequent (and sometimes positive) allusions of later Egyptian Mālikīs to women’s participation in sessions of teaching, preaching, and dhikr.

The relationship between social practice and normative discourse seems to have been complex. Overall, there is a broad correspondence between the teachings of the various madhhabs and the evidence of women’s behavior in regions where they prevailed. The Mālikīs’ comparative receptivity to women’s participation in congregational prayers corresponds to the relative frequency of references to women’s presence at Friday prayers (and the construction of designated spaces to accommodate them) in North Africa and Spain. The Ḥanbalī jurists’ broad affirmation of the permissibility of women’s mosque attendance is well reflected in the Syrian milieux in which they were most strongly represented (including both in Ḥanbalī villages and in the scholarly circles of al-Ṣāliḥīya in Damascus). At the other end of the spectrum, the restrictive teachings of the later Ḥanafīs find expression in the apparent sparseness of women’s presence at congregational prayers in Ottoman Istanbul. To the extent that Shāfiʿīs were strongly represented (both numerically and politically) in Mamlūk Egypt and Syria, the abundance of evidence for women’s presence in mosques (with a particular preponderance of references to their participation in sessions of preaching and teaching) may reflect both the school’s fair degree of legal receptivity to women’s presence in mosques and its lack of specific emphasis on the merit of women’s participation in congregational prayer with men. (The Shāfiʿī case is the most difficult to interpret, both because of the lack of a uniformly Shāfiʿī milieu within our sample and because of the wide variation of opinions on this issue expressed within the school.371)

Nevertheless, within these broad parameters women’s patterns of mosque usage show a diversity and vitality that could not be anticipated on the basis of the legal texts. Many of the activities for which they flocked to mosques in the greatest numbers (for instance, to celebrate on the nights of the great noncanonical festivals) are neither mentioned nor condoned in the standard legal compilations, and their appeal can be explained only with reference to the women’s own preferences and agendas.

Furthermore, if the evidence suggests that legal doctrine influenced or constrained women’s mosque-going behavior, it also suggests that women’s behavior had an impact on the thinking of legal scholars. As we have seen, the relative ubiquity of women in Syrian mosques in the Mamlūk and early Ottoman periods is well documented in our sources. It is probably no coincidence that Damascene scholars of the Mamlūk period produced some of the most accommodating positions on women’s mosque attendance in the history of the debate on that subject. Syrian Shāfiʿī ḥadīth scholars (as well as some of their Egyptian colleagues) reframed the issue of women’s mosque access as a question of the pious and decorous deportment of individuals rather than of blanket assumptions about the seductive potential of premenopausal women. It is also likely that the affirmation of women’s right to attend mosques by Syrian Ḥanbalīs from the seventh/thirteenth century (which is arguably greater than could have been anticipated based on the doctrinal history of the school) reflected, as well as enabling, the striking presence of Syrian Ḥanbalī women in mosques.

However, the substantial presence of women in mosques did not always elicit affirmative reactions from scholars; it also stimulated unusually vigorous resistance and condemnation. Indeed, the extent and visibility of women’s presence in mosques in Mamlūk Syria and Egypt seem to have elicited some of the most vigorous legal argumentation on both sides of the debate, including vehement denunciations from scholars such as al-Ḥiṣnī and ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn al-Bukhārī. The writings of scholars such as Ibn al-Ḥājj, al-Bukhārī, Shaykh ʿAlwān, and al-Dajjānī, who both passionately deplore women’s presence in mosques and vividly describe it, suggest that some of the most categorical prohibitions of women’s mosque attendance may have been evoked precisely by the magnitude of women’s presence in mosques.

Mamlūk and early Ottoman Syria and Egypt are not unique in this regard. The evidence suggests that Ibn Rushd, whose single-minded focus on the problem of fitna and postponement of unrestricted female mosque attendance to the final stage of life formed a turning point in the Mālikī treatment of this issue, would have witnessed extensive women’s mosque attendance in Cordoba.372 This trend is also exemplified by Ibn al-Munāṣif, whose assertion that women should be discouraged from going to mosques altogether is overtly elicited by the presence of young and nubile women at Friday prayers.

Overall, the evidence collected here suggests that legal doctrine had a discernible impact in defining basic parameters for women’s presence in mosques, particularly in terms of its overall magnitude. However, legal texts do not allow us to predict the nature of the concrete activities that women chose to pursue; juxtaposition of legal and nonlegal sources suggests that jurists did not succeed in setting the ritual agenda for most women. Furthermore, to the extent that there is a clear connection between the sentiments of legal scholars and the behavior of women, the jurists’ role was often reactive; in many cases, scholars were left to bemoan activities that they were unable effectively to control.