Chapter 18

One Win Good, Two Better

Prime Minister John Diefenbaker sat with his minority government of 112 Progressive Conservative MPs facing, across the Commons aisle, the shocked ranks of 105 Liberals and the combined 44 Social Credit and CCF members.

Among the CCF MPs was Douglas Fisher, who’d entered the House dubbed a “giant killer” because he’d handily defeated the Liberal’s most powerful minister, C.D. Howe. Nobody had thought it possible, including the PCs, which is why no effort had been made to run a strong Tory candidate in his Port Arthur riding, a factor contributing to the hulking librarian winning the seat.

Other prominent Cabinet ministers had gone down, too, oblivious to their crumbling support, thinking the immense crowds flocking to John Diefenbaker’s rallies were merely curious folk going to watch a freak show, not a political phenomenon manifesting historic change.

Tory representation in Atlantic Canada rose from five to twenty-one members. In Quebec, the PC ranks remained about as slim as when major campaign spending took place: nine seats out of the province’s seventy-five. In Ontario, the number of PC representatives climbed from thirty-three to sixty-one. On the Prairies, PCs edged up from six to fourteen seats, while in British Columbia, the three became seven. Diefenbaker won where the party already had strength and Progressive Conservative provincial governments were in power. In his own home province of Saskatchewan, and in neighbouring Alberta, the Diefenbaker-led PCs still came third in popular vote and claimed only a few scattered constituencies.

———

With Dief shaping Canada’s first Conservative government since 1935, Norman Atkins wound up his campaign duties with Dalton and, a fresh university grad, began a new stage in his own career.

Working in Montreal for one of Canada’s most powerful companies, twenty-one-year-old Norman had landed a position in the accounting department of Canadian Pacific Railway. From his small desk he began to see the grand workings of a vast, interconnected system that depended for operational success on careful attention to detail in schedules, bookings, rates, maintenance, supplies, revenues, records, payments, and logistics.

The accounting department, though removed from the front lines of CP’s integrated transportation, accommodation, and communications businesses, opened a window for Norman onto the company’s agglomeration of freight trains, passenger trains, national and international airline operations, coastal and inland ships, prestigious hotels, and telegraph services. He could also see at CPR how, by 1957, the individual freedom offered by private automobiles and the increasing speed and comfort covering wide distances with airplanes were combining to eclipse the golden age of passenger trains.

Norman was just getting into a new groove, working in CPR’s impressive bustle and enjoying a young bachelor’s life in Canada’s most cosmopolitan city, when he was called to sign for a special delivery letter.

Norman Kempton Atkins stared in stunned disbelief at his U.S. Army draft orders. Though fitting in as a Canadian, he was American. Two years compulsory military service was now demanded of him by the Land of the Free.

Instinctively, he turned to Dalton for advice. After thrashing out such alternatives as getting a deferral by attending law school at UNB, Norman decided, reluctantly, that he should benefit from the army’s training and get paid to “see something of the world.” To reassure fretful Norman that his future would be secure, Dalton said, “I don’t know what I’ll be doing in two years, but whatever it is, you can be part of it.”

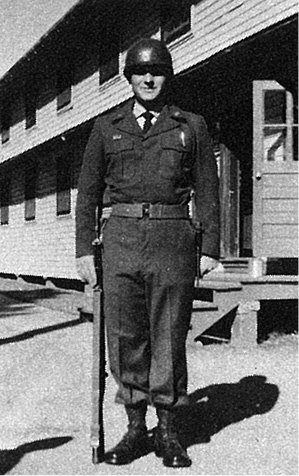

Lance Corporal Norman Atkins was quarter-master in 1958, organizing and running supply operations at a U.S. Army base near Koblenz, West Germany, training that later helped him run Canadian political campaigns “like a military operation.”

On September 9, 1957, Atkins dutifully reported to Fort Dix. Two weeks later, after completing a battery of aptitude tests, he was transferred to Fort Benning in Georgia for basic and advanced training as a quartermaster. His test results disclosed a natural talent for planning and supply that would not have surprised his fellow students back at Acadia. They’d seen him gravitate to the students’ union management board, volunteer to help organize the catering services, run student events, and become chairman of their management board.

Training to be a quartermaster, Norman’s time alternated between classroom instruction and field training. He was taught leadership skills and schooled in operational tactics. He was repeatedly drilled in how to maintain and operate the weapons and vehicles used by a quartermaster platoon. When this round of training was complete, Norman was elevated to acting lance corporal, appointed supply clerk in Mortar Battery 30 in the army’s 3rd Infantry Division, and sent to Germany’s Rhineland where he reported for duty at the U.S. Army base near Koblenz.

———

In Ottawa, meanwhile, the Diefenbaker government, pumped with energy and excitement, was kept on its toes because across the Commons aisle sat enough MPs to defeat them and trigger a new election at any moment.

At first this risk was low because the Liberals were preoccupied choosing a new leader. But once Lester Pearson replaced Louis St. Laurent in January 1958, the new matchup could come any time. Amazing though it seemed, the Grits had lost none of their arrogance. The fresh Liberal leader rose in the House and asked Diefenbaker to resign and hand over the national government to him. No defeat in the Commons, no election in the country, would be required for a Liberal return to office as Canada’s natural governing party.

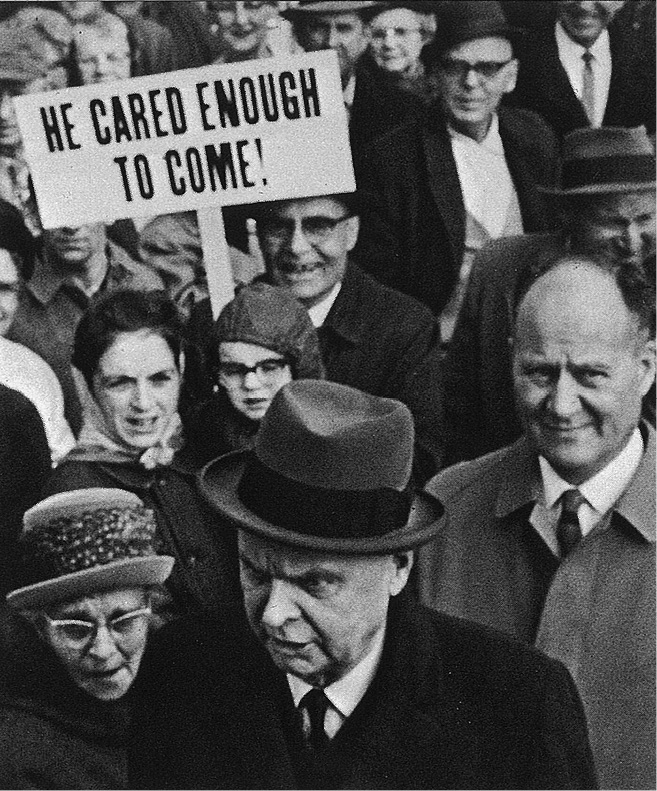

John Diefenbaker was in his element campaigning along any main street in Canada. The Chief himself is credited today for coining the still-popular term “mainstreeting” to describe his populist form of electioneering.

The preposterous stance — based on the limp ground that a Liberal restoration was essential because an unexpected economic downturn was showing the Conservatives incompetent to govern — flouted the people’s verdict in the recent election, centuries of parliamentary precedent, and the Grits’ own credibility.

John Diefenbaker replied by calling another election. Let the people decide!

———

Allister Grosart would again be campaign chairman. The Diefenbakers would once more tour the country by special train with a similar entour-age of staff and reporters. Dalton Camp would run national advertising for the Progressive Conservative campaign and, as in 1957, also direct the campaign in Atlantic Canada. It was as if the first election had been a dress rehearsal.

Two elements in the 1958 campaign that were different from the earlier election reflected a political realignment underway in Canada. One was the reversal of the prior year’s Quebec strategy to ignore unwinnable seats. The second entailed regaining ground on the PC Party’s conservative flank, which some simplistically dubbed its “right wing.”

For the first, voters in Quebec, savvy about political positioning, had no trouble discerning the popular trend flowing toward the Diefenbaker government and knew they’d be better off with those in power than sticking with the increasingly unappealing Liberals. Moreover, in 1957 les rouges had been led by proud Quebecer Louis-Étienne St. Laurent. His replacement, Ontario’s Lester Bowles Pearson, removed that tug of kindred loyalty.

Another part of this shifting Quebec configuration unfolded behind the scenes. In the precincts and parishes where campaigns are fought and won, the Union Nationale political machine of Premier Maurice Duplessis was being deployed in full support of the federal bleus. The plan Duplessis first devised with Robert Manion back in 1939 would finally be implemented for Diefenbaker, almost two decades later.

On the second front, to the west, the Social Credit Party’s support eroded as the 1958 campaign advanced. Before the 1957 election, some Canadians predicted Social Credit, having ditched its radical monetary policies and opted for basic conservatism running Alberta’s provincial government, might in time displace the Tory Party. Others wanted more im-mediate action, lamenting how Socred and Tory candidates were splitting the vote, weakening each other’s chances in many ridings and helping CCF and Liberal candidates. It was time to realign conservatives who were dividing themselves, they said, and “unite the right.”

None of these landscape architects, in reimagining the political terrain, had envisaged how the popularity of John Diefenbaker would pull most Social Crediters away from their party. Instead of a party merger, what a simple, unexpected solution!

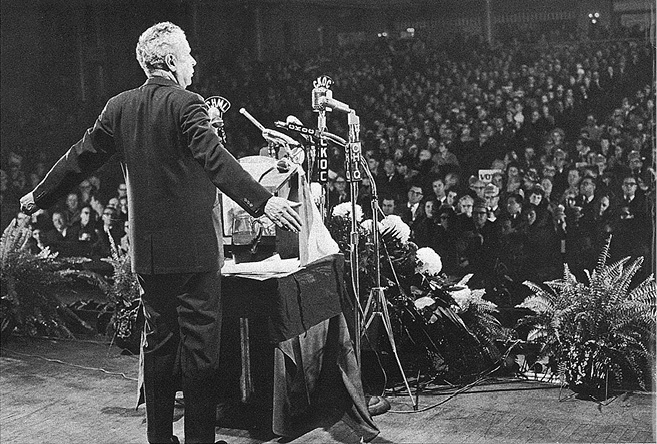

John Diefenbaker arrayed speaking notes, clippings, and letters on a podium the way an artist spreads colours on a pallet, ready to dip into whatever seemed needed next. His speeches were a dramatic art form. Dalton Camp, in charge of party publicity, helped with notes for Dief, and made sure photographers got shots like this one of The Chief performing for Hamilton Tories.

With these changes in Quebec and western Canada, Les Frost’s support in Ontario, and Dalton’s efforts in the Atlantic provinces, where Stanfield and Flemming were going all-out, it seemed the PCs might even win a majority of seats this time.

“It was one of those extraordinary campaigns,” said Camp, “when it was almost criminal to do anything.”

———

On the electrifying night of March 31, 1958, just nine months after the last election, as vote counts flowed in province by province, John Diefenbaker’s minority government was transformed. The Progressive Conservatives had the largest majority government in Canadian history.

Enthusiasm for Dief the Chief was high. Eighty percent of all eligible voters cast ballots. The Tories climbed to 54 percent in popular support across the country. The gain of ninety-seven more seats pushed the PCs to a total of 208 in the 265-member Commons. Overall, the Grits had foty-eight seats, the CCF just eight.

In four provinces — Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, Manitoba, and Alberta — the Diefenbaker forces claimed every available seat. In Diefenbaker’s once begrudging home province, his candidates won all Saskatchewan seats but one. Social Credit voters, numbering 437,000 in 1957, dwindled to 189,000 over nine months, going from 7 percent of total popular vote to 3 percent, not huge numbers but enough to make a difference in ridings where vote splitting was a determinant. This realignment enabled the PCs to pick up all nineteen seats Socreds had won in 1957, including Alberta’s seventeen, and also claim many more seats previously held by Liberals or CCF members, by reducing vote splitting between Tories and Social Credit.

Across battleground Ontario, the Tories won sixty-seven ridings and held the Liberals to a meagre fourteen. Emerging from Quebec’s political earthquake, the PCs had doubled the Liberals, taking fifty seats to their twenty-five.

Dief’s first election win had come as a stunning surprise. The second was one for the record books.