Chapter 19

Advance of the AdMen

John Diefenbaker formed his majority government. The Progressive Conservatives were solidly entrenched, with adman Allister Grosart running the party organization. Dalton travelled to Ottawa often, but not for campaign or political work. There was little point trying to call on The Chief, because Diefenbaker was hardly seeing anybody.

Camp was in the capital, instead, handling a great deal of new advertising work from the Government of Canada, including the tourist bureau account. After the Liberals lost power in 1957, the Grit-enmeshed Cockfield Brown agency soon lost its lucrative federal advertising contracts, too. With a change in government also came change in the ad agencies servicing the government.

Advertising agencies had been incrementally reversing the client-supplier relationship, no longer taking a subservient role under direction from the party, but instead directing the party themselves. Camp had been part of this realignment. His tightly focused political texts for campaign ads had helped turn the tide of elections in New Brunswick, then Nova Scotia. His partisan blasts failed abysmally in Prince Edward Island, but there was no escaping the larger point that he was the one creating and issuing those political messages for the PC campaign. Advertising executives were at the helm, for better and for worse.

Allister Grosart of McKim Advertising handled the agency’s account with the Progressive Conservatives, ran the convention demonstrations for John Diefenbaker’s leadership win in 1956, and battled rival adman Dalton Camp over party policy.

The advance of the ad guys was slowed by performances that fizzled. Dalton’s effort in PEI’s 1955 election had demonstrably been counterproductive. McKim’s orchestration of the 1949 debacle, for George Drew’s first campaign as national PC leader, was an ineffectual but extravagant advertising effort culminating in a solid, full-page ad of illegible type in all Canada’s daily newspapers. The party’s national director, Dick Bell, saw it for the first time when he’d opened his newspaper. He gasped, broke down, and wept. In 1953, for Drew’s next election, Grosart outdid McKim’s 1949 performance with his single-issue tax-cut campaign, helping the PCs lose even more seats.

The point was not how good or bad the policy or its presentation, but that the battle to determine the message — in 1953 advanced relentlessly by one adman, Grosart, and strongly opposed by another, Camp — was being fought by admen rather than by the party members themselves. Dief’s order to burn all policy resolutions approved by delegates at the national convention was a dramatic, undisclosed step in this transition, giving Camp the green light to devise the PC’s complete campaign marketing strategy for the 1957 general election himself.

———

If the admen were on the ascendant in politics, it was because by the late 1950s advertising had come to impart an aura of potency to its practitioners in all realms.

“Style” was important.

Following the dress code of New York’s Madison Avenue agencies and the mannerisms projected on screen by Hollywood, account executives like Dalton got ribbed by Finlay MacDonald for his “grey flannel suit and nightly pilgrimages to the Martini Belt.” Admen were edgy, opinionated, zany, constantly rotating between brainstorming sessions and client boardroom presentations, long lunch meetings in good restaurants, and even, occasionally, their own homes.

But the “message” was everything.

Dalton had been reading a raft of ground-breaking books from the United States on psychology, politics, advertising, mass communication, and techniques for altering patterns of human behaviour. Vance Packard’s 1957 book The Hidden Persuaders, with its exploration of “subliminal” messaging, provoked a debate about the distinctions between persuasion and manipulation, which became integral to the rapidly changing world in which Dalton operated. New theories, experiments, and practices altered traditional ways of advertising and political communication. The adman held the key to powers that could, across great distances and through a variety of communications media, change the thinking and alter the behaviour of complete strangers who, among other things, voted in elections.

A transformation in party campaign advertising was also underway on the business side, in the shift from use of a single agency to several. In the 1940s, when parties began turning things over to advertising firms, they tended to have one preferred agency. MacLaren Advertising had a steady relationship with the Liberal Party of Canada until ousted by Cockfield Brown, which then became the Grit agency of preference. The Liberals in New Brunswick stuck with Walsh Advertising. McKim had a lock on work for the federal and Ontario Progressive Conservatives. With each election, this nexus between adman and politician became more intimate.

But a crack opened once Dalton and his Locke Johnson agency were rewarded with New Brunswick’s account for tourism publicity, then opened wider when Dalton was invited in 1953 to help the federal PCs with campaign advertising, even though the party’s work at the time was in McKim’s hands with Allister Grosart. Two agencies might share the same party’s work.

By April 1957, when Dalton, in full charge of Progressive Conservative election publicity made his presentation to the National Campaign Committee, he was astonished by the presence of so many admen. Allister Grosart, who chaired the meeting and was overall campaign chairman, was the solid link with McKim. Arthur Burns was present for his own agency, Burns Advertising, as was Mickey O’Brien of O’Brien Advertising from British Columbia. Camp was accompanied from Locke Johnson by Bill Kettlewell, Hank Loriaux, and Jim Mumford, the agency’s media director. “It occurred to me,” quipped Camp, after surveying them all, “that Diefenbaker had more advertising agencies than General Motors.”

John Diefenbaker invented this all-inclusive National Campaign Committee. In addition to those whose party office or high standing required they be included, The Chief had further populated the unwieldy sixty-two-member body with his own trusted supporters and many admen. Just as he would never entrust his fate to a single person, he refused to place his fortunes in the hands of one advertising agency.

The Chief liked to divide, in order to gain and maintain control. If he could not divide a single ad agency, he could achieve the same result by multiplying them. This example of many agencies getting a share of the publicity work planted an idea with Dalton. What if, instead, the best and brightest from a number of different agencies were pulled together in a separate, ad hoc entity to handle all aspects of campaign advertising and publicity? It might be something to try, someday.

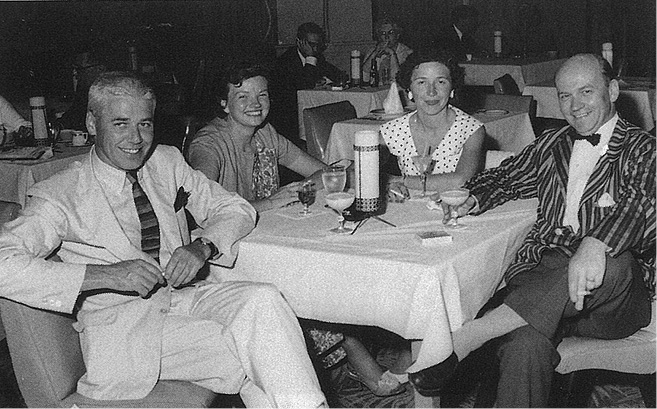

Halifax broadcaster Finlay MacDonald and wife, Ann, with Linda Camp and her adman and backroom organizer husband, Dalton, vacationing together in the Bahamas, basking in the afterglow of the historic 1958 Progressive Conservative election win.

Dalton also observed something else. The ad agencies had taken a hands-on role in 1957 campaign: filling orders for pamphlets, sending out photos of The Chief, and ordering further printings of brochures to meet the rising demand. Such tasks might, in a future election, be pulled together into a single-purpose campaign operation of the party, rather than handled exclusively out of party headquarters or by advertising agencies. A dedicated off-site campaign organ-ization, in harmony with the rest of the party’s election operations, would provide greater control and assurance that everything was being done right by whoever was responsible for running the campaign.

The campaigns he’d seen were run from a premier’s office, or party headquarters, or an ad agency’s facilities. All had other things to do, as well. Why not a free-standing operation, allied with the party, whose only purpose was to run the election campaign?

———

By summer 1959 Dalton was convinced he had to advance in his personal advertising career. He was now thirty-seven. He and Linda had a growing family. Dalton’s daily fare provided scope for writing, both as a leading copywriter in Toronto’s advertising universe and in PC campaigns, but he wanted to do more “serious” work, writing for magazine and book publishers, perhaps even try his hand at a novel.

He’d learned much about the craft of commercial advertising and had honed some unique skills in political advertising’s rarified realm. It was time to rise as a partner in Locke Johnson. He could use more money, wanted the prestige, and believed he’d earned an ownership interest in the firm based on the lucrative accounts he’d brought in during his seven years with the agency.

He arrived with confidence and made his pitch to Willard Locke. He did not even glance around the offices on Davenport Road for a last look as, moments later, he stormed out.

The shock of being turned down was the jolt Camp needed to realize that, if he was bold enough, he had even better future prospects than becoming a Locke Johnson partner. With his own promising political career, and the rising prospects for Progressive Conservatives on many fronts, Dalton Camp would launch his own advertising agency.

As quickly as he found midtown Toronto office space at 600 Eglinton Avenue East, he had a sign painter imprint DALTON K. CAMP & ASSOCIATES on the door. The place was far enough from the city’s downtown’s congestion to be calm, yet close enough to the action to be mentally stimulating.

He invited his talented friend Bill Kettlewell, who’d worked closely on the Maritime and Diefenbaker campaigns, to join him as a business partner. Before the two linked up at Locke Johnson, Bill had been artistic director at J. Walter Thompson. Dalton also enticed Fred Boyer, another skilled veteran at Locke Johnson, to join them as a third partner. They hired staff and set themselves up for a fresh start in a business they all relished, with greater freedom, more money, and a stronger focus than ever on Tory interests.

Dalton’s departure not only deprived Locke Johnson of three of its most talented admen. He also took with him a number of his revenue-producing advertising accounts, including the tourism work for New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and the Government of Canada, a solid foundation to launch his new agency, provided he and his team could keep Tories in office.

———

Hardly had his lawyers completed the incorporation of Dalton K. Camp and Associates Limited in September 1959 when Norman Atkins, having served his country, was back in Canada, discharge papers in hand, to take up Dalton’s pledge of work.

Atkins was a novice to the advertising business. Kettlewell and Boyer were skeptical. But Dalton knew his brother-in-law’s abilities. “He was confident I could do the job,” said Norman. “I worked hard, people took me under their wings, and in six months I was okay.”

Camp himself laughed about his brother-in-law’s baptism of fire. “He had a tough apprenticeship and then made his own way. It was a great endorsement for nepotism.”

The firm handled ad campaigns for such corporate clients as Clairtone electronics and Labatt’s breweries, and expanded its rarified promotional expertise in the tourism industry. As Norman mastered more aspects of the business, he was given greater responsibility as Dalton’s alter ego. He oversaw office operations, handled clients on his own, got commercial spots produced and booked onto television and radio, and administered production of advertisements, whether for billboards or the pages of newspapers and magazines.

With Dalton becoming more involved in politics as the 1960s progressed, any vacuum his absence created at the agency Norman handily filled. Even when working together, they complemented rather than overlapped one another, with Norman increasingly absorbed in operational practicalities that held less interest for Dalton.

Two years of national service had convinced Norman that a rigid organization such as the military was no place for him. He never again worked in a structured environment. Instead, he thrived in the demanding world of an advertising agency, not far removed in nature from the pulsating dramas of a political party’s campaign backroom.

With hard work and long hours, Norman proved adept at running the office, dealing with clients, completing media buys, and keeping track of every pencil.

———

Most advertising agencies focused on traditional accounts for major corporations, some occasionally handling election work when that aligned with the partisan leanings of the firm’s senior partners or a particular in-house aptitude.

In this constellation, the Camp agency stood apart. Dalton had more than “partisan leanings.” Driven by two fundamental imperatives, he was vindicating his decision to quit the Liberals and join the Progressive Conservatives, and making a viable business of the firm that now bore his name. Advertising provided a robust revenue flow, which helped attract top talent, develop pioneering techniques, and gave him the financial resources to be a player in the political arena. The agency, not a seat in Parliament, was still his power base for now. Advertising was a wiring system connecting all parts of the increasingly sophisticated apparatus Dalton was creating, one he dreamed might carry him all the way to 24 Sussex Drive.

Tourism was the ideal kind of account for an agency whose highest specialty was an election campaign. The tourism “product” was a destination, an experience, a personal encounter with the good life. Selling somebody on a destination was, at heart, an appeal to emotions about finding something better than they had ever experienced before. If Camp and his admen could persuade more folks to vote for John Diefenbaker, or for the Tories in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, they could sway them to enjoy touring Canada and spending their vacation dollars for the benefit of Canadians in the process.

The kind of advertising that interested Camp and his hand-picked business partners was not the narrow hard-sell promotion to boost consumption of a particular brand of toothpaste, automobile, cigarette, or soft drink. Because he’d come to the world of advertising through politics, and had not changed, Dalton only found resonance in the higher latitudes of persuasion, the space where one connects with real people over things that matter in their lives, showing them a pathway into a more promising future.

In the bargain, the advantage for the Progressive Conservative Party was having a true blue advertising agency reliably standing by to provide politically astute messaging, buy space in newspapers and air-time on radio and television in elections, while more or less working for free.