Chapter 21

Provinces Red, Provinces Blue

The provincial scene was where Dalton, with Norman, had launched into Canadian political campaigns, and the fate of provincial parties remained an enduring determinant for their electoral operation and their advertising firm.

When Dalton wore his national organizer’s hat, working with Bill Rowe, their building-block strategy was all about winning nationally through PC strength in the provinces. When Dalton unexpectedly landed New Brunswick’s tourism advertising, creating a precedent he thereafter followed while wearing his ad firm’s hat, winning in the provinces was also good for business.

In 1960, Dalton and Norman became engaged in two Maritime campaigns at the same time. Nova Scotians would vote June 7, New Brunswickers on June 27. Atkins was glad the two events had even three weeks between them, since he was communications and production coordinator for both, entailing daily supervision and constant action in two separate theatres of political battle.

Norman now had far more responsibility as Dalton’s assistant than in earlier Maritime campaigns and applied the organizational drills he’d honed to near perfection in the U.S. Army, blended with newer skills acquired at the Camp agency. He was hardly starting from scratch. Familiarity with Maritime provincial politics enhanced his confidence. Norman’s little black book, as constant a companion as his wrist watch, contained names and numbers for hundreds of friends and contacts throughout both provinces.

Writing speeches for Bob Stanfield, Dalton had become indispensable to the Nova Scotian, who’d remarked, in a typically languid endorsement, that he’d “rather not go into an election without him.” With the party controlling government, aggressive constituency-level organizers like Halifax’s militant Rod Black now taking province-wide roles, and smooth Finlay MacDonald coordinating broadcasts and other media outreach with Norman, Dalton’s focus narrowed to the government keeping power and his agency retaining the tourism account.

The results were good. Robert L. Stanfield was now as entrenched in power as Angus L. Macdonald and his Liberal machine had once been. When the votes were tallied on election night, the Stanfield-led PCs claimed twenty-seven seats in the House of Assembly, where they’d face fifteen Liberals.

———

Over in New Brunswick, the campaign was not going nearly so well.

For a couple of terms after Hugh John Flemming’s PCs came to power in 1952, marking Dalton Camp’s own arrival in the backrooms of power, everything had been good. But as the 1960 campaign unfolded, the Grits succeeded in turning a hospital tax into a scalding issue. No words Dalton could write for Hugh John to speak, no advertisements about the exceptional record of Flemming’s progressive government, no blandishment of benefits to voters in close ridings, could stem the emotional force of Grit outrage over a hospital tax, a single negative trumping all else.

The Liberals won with thirty-one members elected, putting the PCs back in Opposition with twenty-one. With only two parties, the electoral system had mirrored the popular vote across New Brunswick accurately, since the Liberals had a modest majority of all votes cast, slightly over 53 percent, and the Tories slightly less, at just over 46 percent.

Following the defeat of the Hugh John Flemming government, the Camp agency lost the New Brunswick tourism account, giving Dalton renewed im-petus to get advertising work from Ontario’s PC government. As for the defeated premier, John Diefenbaker named Flemming his forestry minister, a portfolio for which the lumberman from Juniper, who soon entered the Commons in a by-election that Dalton helped him win, was eminently qualified.

———

Two other provinces gave Dalton a chance to see if the building block strategy, by which New Brunswick and Nova Scotia helped Diefenbaker edge narrowly past the Grits in 1957 to provide a launching pad for 1958’s historic victory, could work in reverse. Forthcoming elections in Manitoba and Prince Edward Island could test whether a strong PC government in Ottawa would help raise non-Tory provinces into the blue.

In Manitoba, peppery Duff Roblin had already made a strong appeal for help to Dalton Camp and Bill Rowe when, at age thirty-seven, he’d just become Manitoba’s provincial Tory leader in 1954.

Roblin faced a complete rebuilding job of the provincial party, and “rebuilding” wrongly suggests there was even a structure to work with. For decades the provincial Tories and Grits shared a governing coalition that had operated under different names, most recently Liberal-Progressive. By the early 1950s, many Progressive Conservatives had become restive in the stale coalition. Under the leadership of Errick Willis and then Roblin, this group broke away and became a new Progressive Conservative force in Manitoba’s political arena. With a $5,000 cheque from the Ontario Progressive Conservative chief fundraiser Beverley Matthews, Roblin was able to get started. With an office provided by Rowe and Camp, he established a base of operations.

To this point, Manitobans could only choose between two parties, the CCF on the left and the Liberal-Progressives on the right, with little in between. Duff staked out the political centre by emphasizing a Progressive Conservatism akin to Diefenbaker’s. With a provincial election looming for 1958, Dalton flew to Winnipeg and reported for duty.

He was not surprised that the proud provincials craved the benefits distant professionals could provide, but were loath to let anyone know about their outside help. Bringing in a “foreigner, that is, non-Manitoban, for a provincial election was anathema,” sniffed high-minded Roblin, “you just didn’t do that.” Roblin had his team “go to some pains to conceal Dalton’s whereabouts. He was not advertised as being among those present.”

His “secret weapon” in the campaign, as Roblin called this phantom, brought to Manitoba techniques he’d honed for provincial campaign advertising in the Maritimes. What Camp called his “editorial column,” Roblin dubbed “Dalton’s daily paid minitorial.” However identified, it was his same unpatented invention: a series of punchy editorials, run as advertisements, in this case carrying the Manitoba PC party logo, each written in his unique blend of edgy criticism, humour, and political savvy.

Roblin did not want Camp in public places, or anywhere political rivals or reporters might spot him, yet craved the good ideas and political insights Dalton could toss off with rapid-fire ease. In private, he also wanted Camp’s complete candour. So he took him fishing in northern Manitoba.

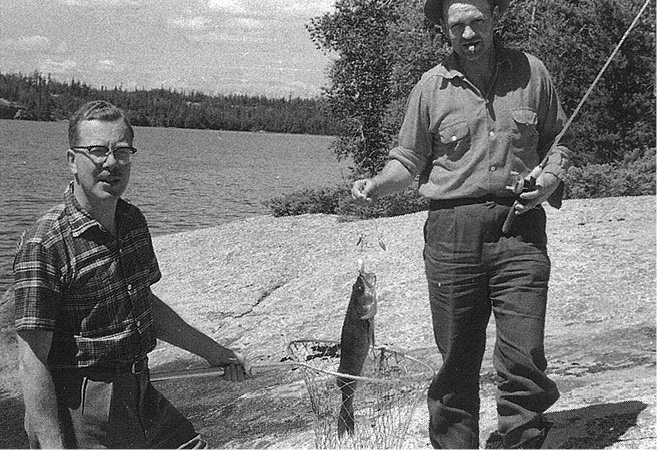

Duff Roblin (left) took Dalton Camp fishing in northern Manitoba to snag good campaign advice while avoiding public attention. The provincial PC leader used bug dope to keep insects at bay. Dalton wisely preferred a good cigar.

Dalton had earlier recommended Duff advance his organization by creating a cohesive sense of purpose among candidates and a common focus for their campaign operations. The meeting he’d orchestrated at Moncton when running the Atlantic Canada campaign, Camp explained, brought together nominated candidates from the four provinces, as well as their campaign managers. The candidates had known little about the PC Party, but a great deal about their ridings, and they’d bonded in the presence of such major Tory personages as Premier Flemming and MP George Nowlan while discussing and adopting the Atlantic Resolutions, PC policy they could advocate in common. The same thing, he proposed, could work for the Manitoba PC candidates and campaign managers.

As for the operational side in the ridings, Camp continued, he’d had tough and talented organizer Rod Black from Halifax in Moncton to coach the campaign managers. Huge credit for Stanfield’s wins belonged to hardcore political operations on the ground in Nova Scotia by Black’s dedicated shock troops.

Duff followed through. Ahead of the 1958 Manitoba election, a two-day meeting of all PC candidates discussed the party’s election booklets and speaking notes. As in Moncton, this Winnipeg gathering brought together candidates who were strangers to one another, unfamiliar about what to do as politicians, and unsure what they would do if the Progressive Conservatives formed a government. The session “was a deliberate effort to make them feel comfortable in their political skins,” as Roblin put it, “and to give them know-ledge of the platform they would support.” A further benefit was psychological, making the candidates feel part of a team and boosting their confidence in the larger campaign and the public purposes of Manitoba’s PCs.

This model was then replicated in a second meeting for the candidates‘ agents and other key constituency organizers. In the field of campaign organ-ization, said Roblin, “We were transforming amateurs into professionals.” Over a couple of days, seasoned campaigners and experts in new approaches instructed attendees about organization, publicity, canvassing, raising money, brochures, different programs and methods for dealing with the electorate, and how to get every last voter who’d indicated support out to the poll to mark his or her ballot on election day. As he observed them, Roblin became satisfied each was gaining a new sense of purpose as part of an integrated, province-wide team, “members of an intelligent, organized, focused approach to the business of getting elected.”

The Progressive Conservatives under Duff’s leadership straddled a significant transition point, not only in campaigning, but in the realignment of Canadian politics. What especially made Manitobans more open to support the PCs had been John Diefenbaker’s advent as a national party leader and Canadian prime minister. Diefenbaker’s background, personality, and political sensitivity reoriented the national Progressive Conservative Party, and its new openness extended into provincial politics and especially Manitoba, home to First Nations, Anglo-Saxon, French, Ukrainian, German, Mennonite, Jewish, Icelandic, and other diverse peoples. The new prime minister, said Roblin, made the Progressive Conservatives “attractive and welcoming to so-called ethnic Canadians” so that “Manitobans of every origin began to see themselves as part of everything we did.”

In the Diefenbaker sweep of 1958, all fourteen Manitoba federal ridings elected PC candidates. Three months later, in June 1958, Roblin’s PCs won enough seats to form a minority government, twenty-six out of fifty-seven, with 40 percent of the popular vote. The Liberal-Progressives became Official Opposition with nineteen members. The CCF elected eleven.

Soon a slogan began circulating in Manitoba, “Duff’ll do what Dief did.” Roblin liked how the sentiment conveyed his association with Diefenbaker’s alchemist powers, and encouraged his candidates and those introducing him at meetings to use Dalton’s line as a prophecy.

For Manitoba’s May 14, 1959, general election, fully two-thirds of the province’s voters showed up at their polling stations, a level of participation not seen since the 1936 election, when, in the depths of the Depression, people also sought to realign politics. This time, the turnout was to finish the provincial realignment begun the year before when election of a PC government ousted a long-running political coalition from office. The Roblin-led PCs climbed to 46 percent in popular support, which translated into thirty-six seats in the fifty-seven-member legislature, a comfortable majority. The Liberal-Progressive coalition still held 30 percent support, the CCF, 22 percent, but ended up with eleven and ten members, respectively. The polarization of Manitoba between “left” and “right” had, for now, come to an end.

The Progressive Conservative wins in Manitoba’s 1958 and 1959 were part of a larger political transformation, emergence of a Progressive Conservative party as envisaged earlier when the Port Hopefuls sparked a change in the national Tory Party at its Winnipeg convention. In slow-moving Canadian politics, everything takes time and delayed reactions are the norm. The Roblin Progressive Conservatives, elected a decade and a half later, made good on the early vision, trebling public spending, mostly on health care, social welfare, and education, including construction of 225 new schools.

In the bargain, and with his continuing help in the 1959 campaign, the Camp agency continued to handle tourism advertising for the Manitoba government.

———

Amidst this mood of political realignment in Canada, the Liberals in Prince Edward Island called a general election for September 1, 1959.

The Island had a traditional two-party system. As the political tides rose and fell, Tories and Grits would alternately be washed into or out of office. The question was not about when the next tide would be, because elections came up every four years or so, but just how long before a tide high enough to change things reached the steps of the legislature? The last time the Conservatives had been pushed into office by an electoral wave had been 1931. Since then, at each of six successive elections, up to and including the one in 1955, Liberals had found themselves stranded in office, unable to do anything but exercise power and enjoy the perquisites of government.

Unlike Manitoba, with a socialist party that drove Liberals and Conservatives into a coalition, the calmer Island province had only Grits and Tories. Relatively few voters needed to switch sides to alter which would govern.

By the time of this 1959 election, it had been four years since Camp had last tried to help dislodge the Island’s Liberal government. His interest in seeing PCs reach office remained as strong as ever. Continuation of a Grit regime in the Maritimes was his unfinished business, even a blot on his reputation. Having learned some kind of lesson, Dalton did all his campaign work at a safe remove from PEI, orchestrating everything through his partner Fred Boyer, who’d snuck into Charlottetown to run the PC advertising while staying out of sight.

Doubtless with most credit to Dief’s overarching presence, which federally had accounted for all four MPs representing PEI in the Commons being Progressive Conservatives, the tide came in high and Walter Shaw, a farmer and civil servant who’d become provincial PC leader two years before, led the Tories to victory, forming a majority government with twenty-two seats to eight for the Liberals. Dalton K. Camp & Associates received, from the new PC government, the advertising account for Prince Edward Island tourism.

John Diefenbaker’s big impact on provincial politics seemed highly beneficial, except in Ontario.