Chapter 27

Days of Reckoning

Dalton Camp could see, from his presidential vantage point, that his conference at Fredericton and similar efforts to bind Tories in even fragile unity were insufficient responses to the core conundrum of John Diefenbaker’s continuing leadership. The Progressive Conservatives were in an end-game, with no end in sight.

Throughout the party’s many centres of power, feelings were high, but acceptable solutions few. The earlier botched Cabinet coup, led by Hees and Harkness but countered by Hamilton, proved how messy this fight over Dief’s leadership could be, and how high the cost: losing the power to govern the country.

On February 3, 1965, Dalton presided at a meeting of the Progressive Conservative national executive. It passed a motion that rebuffed John Diefenbaker, a formal sign of how serious the elected party officers and representatives from across Canada felt about the leadership crisis. Their motion, intended to pressure Diefenbaker to quit, might have worked in normal times with most people, but was counterproductive with The Chief. It only provoked him to keep on fighting. He would not relent. Dief relished battle, became focused with a foe. The exhilaration he derived when giving hell to the Grits was the same rush he’d felt, over nearly three decades, fighting other Tories within the party.

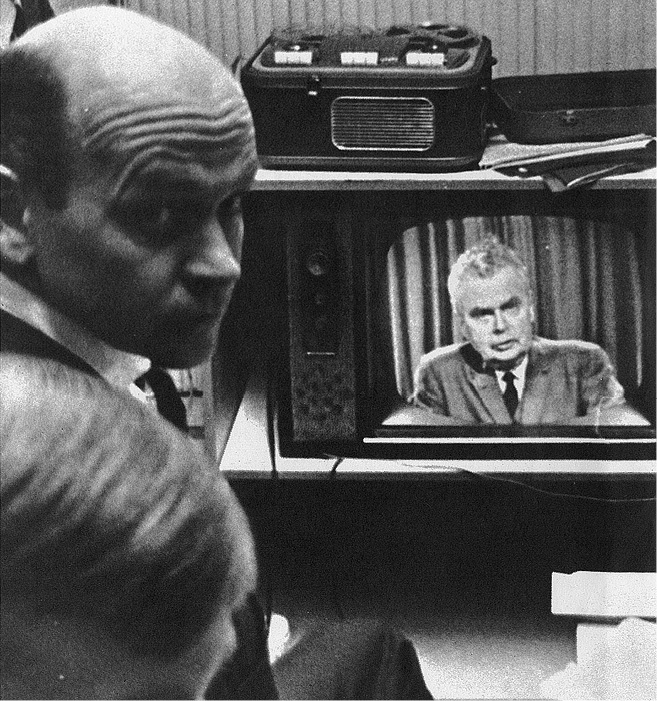

Party president Dalton Camp tried valiantly to figure out what John Diefenbaker would do when under assault from within the Progressive Conservative Party after losing the power to govern. Here, in a hotel room with other backroom blue machinists, he watches Dief declare on national television his intent to soldier on as leader.

Dalton was drawn inexorably into the centre of this political family firefight, trying to identify and hold a patch of authority and power in the uncertain no man’s land between hundreds of thousands of Tory militants engaging in a civil war.

———

Amidst these battles, looking for any happy presidential duty, Dalton wrote Peter Lougheed to congratulate him on becoming leader of the Alberta Progressive Conservative Party.

The party’s inaugural meeting, on March 20, 1965, marked the sprouting of a Progressive Conservative presence at the provincial level in Alberta, a significant point of departure in Canadian politics. Dalton had encouraging words about the new leader one day ousting the long-entrenched Social Credit Party.

Lougheed was heading up a different kind of Progressive Conservative Party, in a province with a political culture as alien to Camp as he was to Albertans. Conservatives had never held power here, and Lougheed, the handsome Calgary lawyer and former professional football player, was building his party from the ground up. It was natural to look for help. Duff Roblin had gone to Toronto for start-up funds from Ontario’s Tories when he’d begun rebuilding the Manitoba PC Party. In the same way, Joe Clark, twenty-six years old and helping Lougheed organize, visited Toronto to meet wiry Hugh Latimer, Ontario PC organizer, for tips, contacts, and support. Hugh was courteous, and gave some limited information, but was certainly not as forthcoming as normal when helping a fellow Tory. As Joe left, Latimer wished him well, but pointed out that Ontario’s PCs worked well with Alberta’s Socreds and both governments considered the other as “friendly.”

Despite the national president’s encouraging words, fledgling Alberta PC operatives could only feel resentment toward the Easterners manning Ontario’s Tory bastion who worked in tacit partnership with their Social Credit rivals.

Such strains between Progressive Conservative encampments across Canada remained mostly unseen by the public. Yet they were part of the reality Camp as the party’s president had to navigate for survival. Lack of Ontario PC support for Lougheed’s new Alberta PCs, due to cozy relations with Social Credit, would in time crest publicly in sharp political differences in Ottawa and at the highest political levels between the governments of Alberta and Ontario over energy, constitutional amendments, and the national party leadership.

———

One way to be aware of dangers lurking beneath the political surface of Torydom was to frequent the Albany Club of Toronto.

Camp, to his disadvantage, was not a member. At heart a loner who happily bypassed established structures, he did not mind. But most Tory players just assumed their national president would belong. One was Senator David Walker, who invited Dalton to join him and others at the club for lunch in the spring of 1965.

Following the meal, Walker made a strong plea for all present to help resuscitate the Albany, with “new blood, so it can survive and grow.” Dalton quickly saw how the club “would be convenient and convivial for a number of purposes related to my political activities,” and told Walker he’d join the board of directors, as requested, except he was not a member. The senator, one of John Diefenbaker’s most trusted advisers, promptly fixed that deficiency by sponsoring Dalton.

On June 1 Camp became both a member of the club and a director of it simultaneously, “an anomaly unique in the club’s history,” he smiled to recall. Soon his friend Pat Patterson became the club’s membership secretary, sparking “an appreciable increase in new members,” including, as Dalton wanted, “many of those closely associated with me in the politics of the day,” such as Eric Ford, Ross DeGeer, and Norman Atkins. This regeneration of the club “was something of a miracle,” he wrote, transforming it from a place “with few members” to one “where almost everyone I knew had become a member.” That was a diplomatic way of saying he and Norman had launched a takeover of the Albany Club.

Dalton believed the Albany’s networks would facilitate his bridging effort as national president. They did that, and more: he discovered, at last, that the entrance to Queen’s Park was actually downtown at 91 King Street East. At the club he developed a warm relationship with Premier John Robarts.

His work as bridge-builder seemed unending, though. New rifts kept opening. The national PC caucus, one of the most visible centres of organized power in the party, itself had many subsections, such as regional caucuses of MPs and senators divided according to provincial boundaries. Quebec PC parliamentarians met separately, as did those from the Prairies and Ontario and Atlantic Canada. In mid-1965, Trois-Rivières MP Léon Balcer, a former president of the national party and Tory Cabinet minister and the man designated by Diefenbaker his deputy leader in Quebec, had had enough. He convinced Quebec Tories at their caucus to support a motion calling on the party’s national executive to meet and set a date for a leadership convention.

Balcer’s ultimatum to the national executive forced Dalton to figure out his next move to keep his fighting partisans from each other’s throats. Balcer was seeking a date and place for the awaited duel. Camp saw other combatants on the field, however. The Liberals were waiting for the PCs to be gravely wounded or even leaderless so they could call a quick election and add the few seats needed for their majority government.

As a solution to this immediate conundrum, Dalton devised a questionnaire, which he put to the national executive in hopes of disposing of the Balcer ultimatum while giving Dief yet another opportunity to step down gracefully. He feared voting on a motion to hold a leadership convention would not carry because most national executive members would worry, as he did, that with Tories in the protracted process of changing leaders, the opportunistic Liberals would call a snap election. On the other hand, if the motion did not carry, Diefenbaker would take it as an endorsement to continue as leader. As debate continued at the national executive meeting, the hardliners on both sides resolved to push all the way, without compromise.

When the afternoon session resumed, the issue came to a head in a deadlocked vote on the motion about Dief and the convention. Camp as president had to cast the tie-breaking vote. He did not do the deed. Eddie Goodman, who, like Hal Jackman, was doing everything possible to move Diefenbaker out of the leadership, left in angry exasperation. “We had them beat,” he criticized, “until Dalton ducked.”

Camp was unwilling to take a public stance against The Chief. He did not want the party caught holding a leadership convention when the Liberals launched an election. Dief, feeling gleeful that he and his loyalists on the national executive had outmanoeuvred both Camp and Balcer, not to mention Goodman, would not step down. Soon Léon Balcer left the Progressive Conservatives to sit in the Commons as a political independent, declaring, “There is no place for a French Canadian in the party of Mr. Diefenbaker.”

For his part, Camp was finally convinced there was no way The Chief would go peacefully, ever.

———

The awkward struggle was unlike anything before in Canadian politics: a protracted public embarrassment involving a raw contest of human wills. Even when Ontario’s premier Mitch Hepburn squared off against Prime Minister Mackenzie King, the two men and their Liberal supporters were separated by distance and different levels of government, and kept the worst of it private.

This Tory feud had an epic quality, but was the protagonist a vanquished man refusing to withdraw in dignity, or a valiant man fighting on nobly against meanest fortune? Either way, John Diefenbaker needed an opposite, and so Dalton Camp became that foil, entering the period of his celebrity, as news reporters covered the drama’s twists with incredulity and the public looked on with fascination, alarm, or disgust.

Through 1965 Dalton accepted a growing number of invitations to speak, the PC president intent on refreshing his party with a contemporary image. The Fredericton Conference had heightened his reputation as an intellectual, adding to his established credentials as a successful campaign organizer, talented speech writer, and brilliant adman. This made him more suspect to certain Tory MPs, who disdained “intellectuals” and pronounced the word with a sneer. Others, however, had become increasingly attracted to Dalton’s plans for the party. Rising interest in Camp convinced The Chief more than ever that his party’s president was his personal rival.

In fact, despite his wish to avoid a party crisis by directly challenging Dief to resign, Dalton had begun to feel that that the time had come for him to finally find a place for himself in Parliament. It was time to extend his power base into the national caucus. A general election loomed.

Bill Davis urged him to run in Peel, northwest of Toronto, where the Brampton MPP’s own political organization could help him win a Commons seat by taking the strong Tory riding. In 1962, capitalizing on the anti-Diefenbaker anger over the Avro Arrow, Liberal Bruce Beer won the seat — “It’s time for Beer!” — the first Grit in the twentieth century to do so. Davis believed conditions had changed by 1965. Yet Dalton took a pass.

He wanted to enter the Commons, not by a side door but through the main entrance, defeating a leading Liberal. Also, it was more practical and credible to run where he lived and operated his business. To make Progressive Conservatives appealing to contemporary Canadians, representing a city riding was the right fit. A breakthrough was needed. Dief and his supporters might appeal in outlying and rural areas, but Dalton wanted the PCs to be contemporary and stronger in urban Canada.

He could lead this reformation by example, retaking Eglinton from Liberal Cabinet minister Mitchell Sharp, the sitting MP. Chad Bark, president of the Eglinton PC association, was urging Camp to run in the riding and, to “test the waters,” speaking engagements were lined up.

When Dalton addressed the Eglinton Young PCs, Brian Armstrong was in the room. Recruited by Bill Saunderson to the PCs three years earlier, when a law student at University of Toronto, Brian had displayed intense interest in politics, working in Eglinton’s 1963 federal and provincial election campaigns. Now, however, he wanted to join the Liberals. “The party under Mr. Diefenbaker was something most young people could not associate with,” he explained, adding it was “an object of ridicule on university campuses across the country.”

At this lowest point, he heard the party’s president speak. “Dalton absolutely blew me away,” he said, “because he was a thoroughly modern Conservative — intelligent, urbane, thoughtful, progressive, incredibly articulate, charismatic, and someone who really wanted the party to open itself to young people.” Armstrong would stay with the PCs, a disciple of Dalton Camp.

When Dalton addressed the Downtown Toronto Kiwanis Club, Roy McMurtry was in the audience. The 1965 federal election had just been called, and it was rumoured Camp might run. As a resident of Eglinton riding, McMurtry had voted for Sharp in 1963 but was impressed by Camp’s “rational and moderate approach to federal political issues.” He heard “a refreshing departure from the pointless partisan bickering that had for too long dominated the national political discourse.” Roy volunteered to assist Camp, if he became a candidate.

Two days later, Dalton declared. Norman, who’d attended all his brother-in-law’s speeches recording names and numbers of those interested in helping him, began working the phones. Among those assigned campaign roles for the Camp campaign were Armstrong and McMurtry.

The campaign headquarters on Eglinton Avenue, a block east of Yonge Street, directly across from the Dalton K. Camp & Associates offices, was convenient because the two operations functioned as one. In the headquarters basement, campaign manager Atkins convened an organizational meeting. Norman had already produced VOTE CAMP bumper stickers to provide mobile visibility for the candidate. He double-checked that everyone attending got their supply.

McMurtry, “despite lack of experience in political organizing,” accepted responsibility for putting together a political team. Armstrong became area organizer for six polls, recruiting a team of canvassers, making sure each poll was canvassed, and identifying all who would vote for Camp. On election day he was to ensure the PCs had poll clerks in each voting station, PC volunteers working the lists and phones, and drivers getting all identified Camp voters out to cast their ballots.

Around the table at this first organization meeting, both new recruits and veteran campaigners were fascinated when Eglinton’s provincial PC member, Leonard Reilly, turned over for Dalton’s campaign his “entire campaign organization,” which he tracked on a system of file cards. “Every person with whom Len had ever come into contact in the riding had a file card,” said Armstrong. “They were in metal recipe boxes: everybody whom he’d helped, who had put up a sign for him, who’d made a financial contribution.” For a starting candidate, this information was a political gold mine.

When they climbed the stairs to leave, each with his or her supply of voters’ lists, brochures, buttons, campaign contact numbers, and other paraphernalia issued by the quarter master, Brian reassured Norman, “I have my sticker and will be putting it on my car.”

———

Intent on getting into Parliament, Dalton concentrated on Eglinton. Norman took no role in the national campaign either, totally focused on Dalton winning Eglinton to better position his run for the leadership.

In place of Dalton, who in1963 had run the federal campaign, this time Eddie Goodman was national campaign chairman. He began by persuading his friend George Hees to return to the fold in a show of unity, and in doing so, flamboyant George helped other Tory dissidents rally to the PC cause. That was positive. Dief was ecstatic.

The Eglinton campaign was civil, even urbane. Camp and Sharp were well matched in the personal campaigning department: both were very poor at it. Neither the adman from the campaign backrooms, nor the civil service mandarin from Ottawa, was at ease meeting strangers. Camp could not glad-hand nor make easy chat, despite having studied carefully John Diefenbaker’s mastery of the art; he seemed, instead, to emulate the style of reluctant Bob Stanfield. For his part, Sharp looked especially awkward at all-candidates’ debates, seemingly miffed if someone in the audience didn’t know the deep implications of policy the way his civil service interlocutors in Ottawa would have. Each candidate could only seem happy, and be fun in a socially outgoing way, with a circle of his own chosen friends, musical Mitchell at a piano, Dalton entertaining with stories over drinks and cigarettes in a bar.

By election night, Camp had failed to attract enough votes. His 16,777 ballots could not trump Sharp’s 18,719. Nor, over in Rosedale riding, had Hal Jackman quite succeeded in his repeated effort to get into Parliament. City seats were hard for Tories in the 1960s. Even in Peel, Bruce Beer got re-elected.

Progressive Conservatives across the country, campaigning on the slogan “Policies for People, Policies for Progress,” did manage to win ninety-seven seats, however. Diefenbaker, to everyone’s astonishment, again held Pearson’s Liberals to a minority. The Liberals remained in government but with only 131 MPs they were still two short of a majority. NDP candidates were elected in twenty-one ridings, the breakaway Social Credit Rally in Quebec, nine, and Social Credit itself, in five. This time the seat allocation was a reasonable reflection of popular support. The Liberals with a minority of votes (40 percent) got a minority of seats; the PCs had 32 percent of the popular vote; NDP, 18 percent, and the two Social Credit groups together, 8 percent.

———

John Diefenbaker interpreted keeping the Liberals to a minority government as a victory.

Feeling vindicated by this outcome, he refused to resign the leadership, although many continued clamouring for him to go. He knew how the Tories’ long years in the political wilderness had not improved party fortunes by changing leaders in the past. He reminded people about political leaders, in Britain and elsewhere, who’d carried on into advanced old age. He purged those he considered threats. When he fired Flora MacDonald as party secretary at national PC headquarters, her extensive network of friends and allies throughout the party were incensed.

With a Liberal minority, another election could come at any time, making a leadership convention problematic, had it even been possible. John Diefenbaker’s continuation as leader left few Tories with the stomach for a battle they saw themselves preordained to lose.

Having led his party into five elections, many Tories and a majority of Canadians felt The Chief had enjoyed all the outings any one man was entitled to. His virtue of resilient determination, which rank-and-file Tories so admired when electing him leader in 1956, now seemed a vice. Resolution of the “leadership issue” would be neither clean, nor quick.

John Diefenbaker was ardent about remaining leader; Dalton Camp was equally resolved to end the conundrum.

The time of reckoning was at hand.