Chapter 28

Showdown at the Château

In the Albany Club’s wood-panelled main dining hall, members gathered on the spring evening of May 19, 1966, heard master of ceremonies Hal Jackman remind them, following dinner, that Dalton Camp’s address was “off the record.”

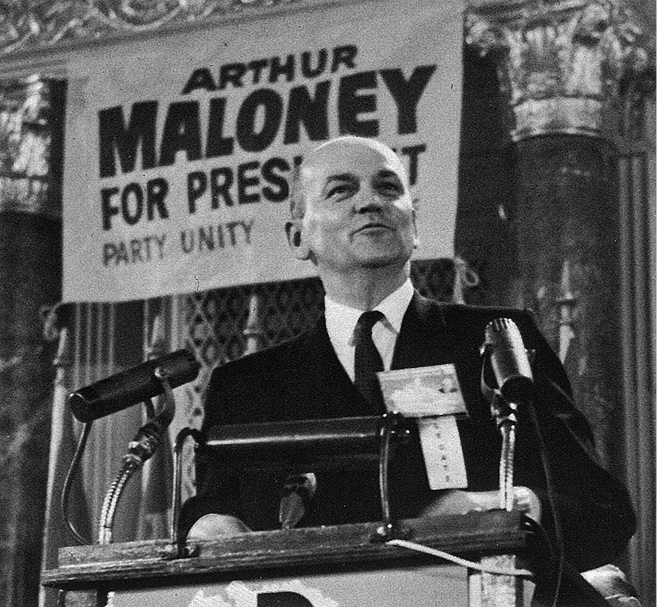

The PC national president outlined, to the hushed attention of some two hundred, his proposition that “leadership of any great political party should be made subject to review.” He said “the party is not the embodiment of the leader but rather the other way around; the leader is transient, the party permanent.” He added, if “the leader does not know the limits to his power, he must be taught and, when he is indifferent to the interests of his party, he must be reminded.”

He spoke eloquently, with care, and dealt with principles. His concept was novel in Canadian politics at the time, certainly not yet a provision in any party’s constitution. While a leadership review clearly applied to the incumbent PC leader, Camp framed the issue in generic terms, advocating a democratic process, a principle rather than anything personal.

Jackman’s father, Henry, among the scores of prominent Tories present, correctly heard the speech “as a direct challenge to Diefenbaker” all the same. He surmised, because Senator David Walker was at the head table, that “Diefenbaker must have known about the speech in very short order.”

Dalton certainly expected word would spread. Next day he began sending out copies. With the one mailed to Finlay MacDonald in Halifax, he wrote, “This was an off-the-record thing to just the party members, but now, I suppose, the balloon will go up.” It didn’t. He’d not imagined club members would dutifully honour his remarks as privileged. No mention was made in the press about the content of Camp’s speech.

Among those present that night was Ross DeGeer, chairman of Toronto’s Junior Board of Trade. As Diefenbaker’s leadership continued to plague Conservatives through the summer, Ross suggested Dalton use the Junior Board’s podium to repeat his message, “this time for public consumption.”

When Camp delivered the identical speech four months later on September 20, the young business-minded members of the Junior Board were attracted by his eloquence and determination. Being intense competitors, they relished a contest for power, a high-stakes game; raw politics, not the canned stuff. Camp, having awakened it, drew on that reservoir of latent support in his non-party audience. Had he been addressing a meeting of Progressive Conservatives, he’d have heard some boos and seen a few stomp out to denounce their president to reporters for treachery and disloyalty to the leader.

Toronto Telegram publisher John Bassett, a major power in the Tory Party, thought Camp and his little group supporting leadership review were hopelessly out of their league and would be shredded by Diefenbaker’s hardened forces. He dismissed them in his newspaper as “the Eglinton Amateurs.”

———

“The cat was truly out of the bag,” said DeGeer, as the speech gained immediate and wide coverage.

“From that time on, Norman and the organization he and Dalton had assembled from across the country as a result of the Fredericton Conference were assessed for their take on this issue, to identify supporters of the leadership review process.” Those they could reliably identify as favouring review, said DeGeer, “quickly became part of the organization needed at the Ottawa annual meeting.”

After the Junior Board speech, Dalton and Norman began what they called a “pilgrimage” to campuses and editorial offices across Canada. Dalton spoke at PC meetings and in television studios, advancing the cause through September and October, taking political temperatures, calculating how to proceed. It was hard to get a good reading. Feelings varied, from supportive to hostile. Dalton’s own emotions swung between buoyant and deflated. Norman couldn’t stabil-ize things because he took his signals from Dalton, who was sending mixed ones, and tended easily to nervous fretting himself.

As party president and issuer of an unprecedented challenge to the leader, Camp was now the public face of an organized challenge to John Diefenbaker. Camp was not only its leader but the lightning rod attracting bolts from Dief loyalists, who described Camp as filled with ambition, a “slick front man for Bay Street interests.”

Yet he was hardly alone. Behind the scenes others were developing scenarios to outmanoeuvre Diefenbaker, too. Davie Fulton, who’d returned to Ottawa in the 1965 election after his quixotic tilt at B.C. politics, was an impatient candidate-in-waiting. In July Fulton told Hal Jackman, who’d been raising money for his leadership bid, that he was “seriously considering going it alone in an attempt to dump Diefenbaker prior to or at the November annual meeting.” Davie knew this would kill his leadership hopes, but was “prepared to do so, for the good of the party.”

Another scenario was Fulton’s plan, suggested by Lowell Murray, to have “the six leading men in the party — Robarts, Roblin, Stanfield, himself, Hees, and Camp — give The Chief an ultimatum.” Davie complained to Hal that he’d suggested this to Dalton but had no response, and was critical of Camp for going public on leadership before lining up this heavy-duty support. Jackman discussed this at length with Atkins on September 27, 1966, then reported back to Fulton that Camp had decided to deal with the leadership issue “completely on his own,” without any assurances of support from the premiers or other leadership candidates, and though aware of Fulton’s proposal for getting five or six leading figures in the party to come forward, “had earlier dismissed the idea as being impossible to organize.”

Atkins also told Jackman that Dalton planned a motion at the annual meeting calling for a leadership convention but, realizing the difficulties in presenting such a motion, he might, as an alternative, “focus the entire battle on his own re-election.” It would be clear by November “that a vote for Camp is a vote against Diefenbaker.”

In the past, Conservative leaders had been changed many ways, initially with Tory MPs and senators performing the task as a caucus, sometimes with the governor general taking a role in Confederation’s early years. Then the task of choosing a party leader passed to a national convention of voting delegates from all constituencies. Sometimes the national caucus chose an interim leader. No matter which of these methods was in play, the selection and replacement of the leader always saw power-brokers in the party’s backrooms pull strings and move others so that leadership transitions could be reasonably swift.

But the rocky, decade-long ride of the Progressive Conservatives under John Diefenbaker was not progressing according to any known pattern. Camp felt Diefenbaker had alienated Quebec, most provincial premiers, and broken unwritten rules. He believed Dief incapable of moderation and saw no smooth end or happy transition. It had only been when he was convinced Dief would not leave until forced out that, as party president, he resolved to establish a new principle of “leadership review.”

———

Dalton faced unprecedented conditions as president, entering no man’s land, challenging the leader’s unaccountable decade at the helm. For what lay ahead, he needed a tightly knit, highly reliable group that could work secretly with machine-like effectiveness to achieve tactical goals.

He already had well-placed political operatives across Canada. Norman, working almost full-time on Dalton’s political activities though keeping tabs on Camp agency projects, did far more than record everybody’s names and numbers. He’d become a proactive organizer. He stayed in constant contact by long-distance telephone with this network of progressives. Though both extensive and reliable, this organization was not enough.

Several hundred Torontonians had come forward to actively support Camp’s bid for a Commons seat in Eglinton the year before. They remained an effective, diverse, and talented squad, anxious for the next election’s rematch. But these Eglinton constituency supporters, the “amateurs” identified by John Bassett, were an unwieldy group ill-suited for the national hardball politics now polarizing Progressive Conservatives.

The power struggle in which Camp was engaged demanded a clandestine cadre within the PC Party itself, a “special operations team” in play for him the way covert squads advance unique missions for military, espionage, and religious organizations.

The clandestine blue machine group the “Spades” knew each other by their playing card identities. Camp was the “Ace” of spades, his brother-in-law Atkins, the “Five.” Three others were “Six,” Eglinton riding PC president Chad Bark; “Seven,” McCarthy lawyer and PC bagman Patrick Vernon; and “Nine,” lawyer Donald Guthrie.

Dalton and Norman formed a secret group to strategize, plot, and carry out projects. From their vast talent pool, they hand-picked seasoned men who’d already performed exceptionally well in campaign operations. Dalton was the group’s magnetic centre, Norman its organizer. Eglinton PC riding president Chad Bark was in, as were downtown Toronto lawyers Patrick Vernon, Don Guthrie, Pat Patterson, and Roy McMurtry. The others in the brotherhood were Bill Saunderson, Eric Ford, Ross DeGeer, and Paul Weed. Saunderson, a chartered accountant, looking around at their first gathering, recognized in his fellow members “interesting, intelligent, active people who all loved politics.” Each came with his own network. None depended on politics for their livelihood.

Saunderson came up with their code name, “Spades,” which initially had the connotation of “doing spadework” to prepare Dalton Camp’s way in national politics, even a loose association with “digging” deep in the party’s grassroots for support. But once Saunderson produced a deck of miniature playing cards and handed the ace of spades to Dalton, that design and identity stuck. From that day on, their code name for Camp was Ace.

Most carried their card, like membership ID in a secret fraternal society, alongside money and driver’s licences in their wallets. But the Spades were men of diverse personalities. McMurtry evinced little interest in this juvenile, “secret-society” feature of the group, while Atkins so venerated his five of spades card he hung it, framed, on his inner office wall. As part of keeping their work hidden, Norman and others referred to one another, in cases requiring ambiguity, by their playing card number alone.

Bark knew a lot of people in Eglinton riding and most old-time Tories around Toronto as well. Saunderson, a chartered accountant in the financial business, thrived on politics as had two of his grandfathers. Ford, a strong and positive man, was a chartered accountant with Clarkson Gordon, a dedicated supporter of his church and community organizations, and Albany Club director and president. Patterson, a partner in the Toronto law firm Stapells & Sewell, was a good fundraiser and recruiter of many younger people at the Albany Club where the Camp forces were marshalling. Guthrie, a bright lawyer of patrician manner who acquired sure knowledge of any topic that engaged him, inherited his political gene from an uncle who’d served in Prime Minister Bennett’s Conservative government. McMurtry was a lawyer, artist, and front-line worker for people’s equality and dignity, a former football player who remained athletic. Vernon was a partner in the prestigious McCarthy law firm and enjoyed a deserved reputation as one of the PC Party’s most reliable and productive fundraisers. DeGeer, an investment dealer who chaired Toronto’s Junior Board of Trade, was ambitious to get into politics, liking policy but also excelling as a hands-on event organizer of Grey Cup parades and international conferences. Weed owned and operated a collection agency and, carrying his no-nonsense ways into politics, was a veteran trench worker for the Tories, adept at getting results, especially when he did not have to explain how he’d achieved them.

The Spades met, usually at the Albany Club but also in their private homes, whenever Dalton needed a sounding board for an idea or tactical action for a political manoeuvre. They frequently discussed how he should proceed, using his role as party president, to braid John Diefenbaker without damaging his own eventual run for the leadership. Camp also consulted individual Spades about specific projects.

As a group, the Spades planned in detail everything for the crucial 1966 annual meeting showdown, which, DeGeer noted, included organizing attendance, debating changes to the party constitution, running candidates for the party’s offices, and recruiting pro-Camp voting delegates in ridings across the country.

They believed history was on their side, seeing John Diefenbaker, as Bark put it, “increasingly anachronistic and authoritarian.” With their Ace as national president, the Spades wielded considerable influence and unseen power in the Progressive Conservative Party.

———

Roy McMurtry, among the Albany Club members hearing “Camp’s principled eloquence” at the May dinner earlier that year, knew many in the party “would regard his challenge as disloyal and unacceptable.” He feared the speech “might affect Camp’s political future,” tacitly understood to include becoming leader himself. Even so, Roy undertook to support Dalton, alongside the other Spades, “in his battle to establish the democratic principle of leadership review.”

As the PC general meeting approached, bringing closer its challenge to Diefenbaker in the form of Camp standing for re-election as president, McMurtry and his friend and mentor Arthur Maloney, a former PC MP and leading criminal lawyer, discussed the leadership conundrum. Maloney was not one of The Chief’s most ardent supporters, though McMurtry “detected that he was uncomfortable with the growing challenges to Diefenbaker’s leadership.” Arthur contended a leader should be able to choose his own time of departure. Roy countered, in a jocular manner to render his serious point to the devout Catholic less confrontational, “The leader should not enjoy papal-like prerogatives.”

A few weeks later, McMurtry took a phone call that stunned him. “Brother McMurtry, get out the Maloney signs. I’m going to challenge Dalton Camp for the presidency of the federal PC Party.”

Arthur Maloney’s candidacy was an inspired stroke by the Diefenbaker forces. He’d distinguished himself in difficult cases for hard-pressed clients. As a member of Parliament from 1957 to 1962, he had impeccable Tory credentials, and worked with Dief on the Bill of Rights. Maloney was well-known and broadly respected by members of the press. And as an enthusiastic and successful campaigner, Maloney was better than reticent Dalton at meeting and greeting others.

His surprise entry into this high-stakes battle caused consternation for many Tories, including McMurtry and Brian Mulroney: each supporting Dalton Camp on leadership review, yet both devoted friends of Maloney, who had been their inspiration as young lawyers.

———

Nobody expected a national meeting electing the president, a proxy fight over continuance of John Diefenbaker as leader, to be pleasant.

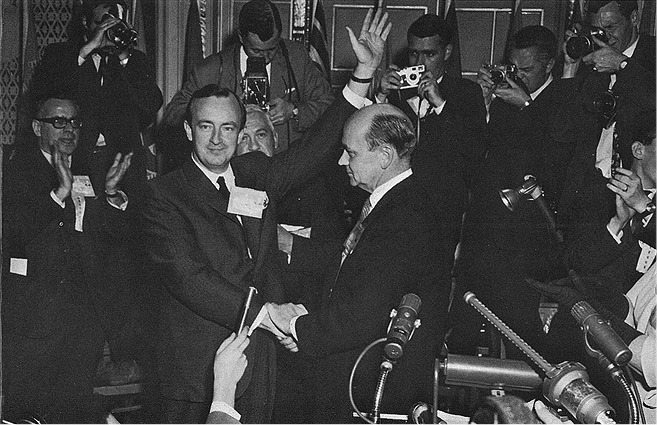

Arthur Maloney, leading criminal lawyer and Progressive Conservative MP from 1957 to 1962, waves to delegates at the confrontational 1966 annual general meeting in Ottawa while shaking hands with Party president Dalton Camp, whom he’s challenging. A vote for Maloney was support for Dief; for Camp, an endorsement of “leadership review.”

Grown men, who had public careers as MPs only because they’d been carried into office by The Chief, openly wept at the prospect of him going down. They would do anything, and everything, to keep him. Yet others were possessed of steely resolve that he must depart. MP Gordon Fairweather of New Brunswick contended that, for the sake of overriding national interest, Diefenbaker must never again be prime minister, “even if removing him required destroying the party.”

Knowing fireworks would explode in Ottawa’s Château Laurier Hotel at the November meeting, the Spades prepared to limit the damage.

The issue of a secret ballot would be central to the showdown. While many PCs had strong feelings about Diefenbaker’s leadership and roared like bears about it in private, they’d clam up in the presence of other party members who might not share their views.

Already the party’s national executive had divided sharply, in several meetings, with angry disagreement over holding a secret vote on matters pertaining to John Diefenbaker, leadership review, or the calling of a convention. Whenever one section of the party mounted a challenge, The Chief’s loyalists promptly engineered an offset response in another section.

As each side’s move in one venue was countered by another elsewhere, the inconclusive political chess match dragged on, wearing people’s patience thin, boring and annoying the public. Reporters spread “news” of the latest move. Pieces fell, but the end-game never came. November’s meeting was intended to change that, but required strategic sequencing of the meeting’s events, from when Diefenbaker would address the gathering in relation to the vote for president, to when secret voting by delegates would occur and the real showdown take place.

Because “leadership review” had become a euphemism for the leadership convention to replace Dief, his loyalists would insist any motion on the subject be decided by open vote, not secret ballot, believing they could publicly intimidate enough delegates to defeat it.

But once Dalton knew he would be challenged for the presidency by Maloney, he realized the all-important secrecy in voting could be achieved by shifting to his backup plan: unequivocally staking his own candidacy on leadership review. Because contested elections were always held by secret ballot, this would circumvent any need to get agreement for a secret ballot on a direct confidence motion about Dief as leader. Voting for Camp, not by a public show of hands but through the privacy of one’s marked ballot, would be endorsement for a leadership convention. It seemed, nodded Hal Jackman approvingly in his diary, “a good strategy,” the deft sort of manoeuvre one expected of Dalton.

Camp remembered, as Diefenbaker’s Maritimes advance man for the 1957 leader’s tour, how The Chief insisted nobody speak after he’d finished, so the impact of his message would be strong, the last thing people remembered. The sequence of events at the Château, the timing of Dief’s speech in relation to voting, was crucial. Because the national executive controlled the meeting’s agenda, Dalton knew that before there was any showdown on the floor with delegates, one had to take place in the boardroom with party officers. It did. A change in the order of proceedings was orchestrated, ensuring that Dief would be unable to unduly sway delegates just prior to voting.

———

Dalton’s campaign for re-election was entrusted to Norman.

None of the Spades wanted big “demonstrations” at the meeting, fearing such shows could escalate the event from an orderly meeting to elect officers and approve an eventual leadership convention into something resembling a leadership race itself. Having floor demonstrations to sway delegates would telescope the two events, complicating an already complex matter. But others, believing in the import-ance of demonstrations to move people in their moment of decision, did not agree.

Hal Jackman, an active player as candidate, participant in the Fredericton Conference, financial contributor, fundraiser, and leading light at the Albany Club, had campaigned hard as the PC candidate for Rosedale riding in 1963, and again in 1965, despite his increasing determination to oust Dief. He now teamed with Alex McBain, chief coordinator of federal PC fundraising in Ontario, and prominent Toronto barrister Joe Sedgewick, “to pay for the travelling expenses of student and YPC members of the national executive who could not otherwise afford to attend the 1966 meeting and register their vote against The Chief.”

As the showdown approached, Jackman remained anxious about the vote and met on November 6 with Camp to review detailed plans. That night he wrote in his diary that Dalton “seems to be light on organizers as far as the actual convention is concerned and, unless he is prepared to counter the emotional pitch which the Diefenbaker people will undoubtedly throw at him, he runs the risks of being snowed.”

Hal pressed for a stronger effort, taking measures to supplement the plans of Camp and Atkins. Because he envisaged the coming event more like a leadership convention than a regular annual meeting, Jackman contacted Eddie Goodman and Del O’Brien about his desire to stage a big demonstration. Goodman, who’d chaired the national campaign in 1965, and O’Brien, president of the PC Party’s youth wing, had to remain officially neutral. But, as Jackman himself noted, “their co-operation in facilitating the anti-Diefenbaker youth delegates to attend the annual meeting reflected their true feelings.” The plan the three agreed to was for fifty students to be bussed in from Toronto, Trenton, and Kingston and kept on standby at Ottawa’s Eastview Motel for events at the Château. “Camp and Atkins have some reservations about demonstrators, but, as I am underwriting the cost with Goodman and O’Brien’s approval, there is nothing much they can say,” recorded Hal. “I feel these things are very important.”

———

Once Dalton and Norman realized this escalation would occur, they decided it could not be a half-measure. They made calls for more money to support and expand the effort. Three student delegates opposed to Diefenbaker would be brought to Ottawa from Saskatchewan, the leader’s home province, not only for their votes but as a symbolic gesture. Norman booked a series of suites in the east wing of the Château Laurier’s fifth floor from which to run Camp’s re-election campaign. Every room in the hotel, and all available spaces elsewhere in the nation’s capital, were filling up with Tories come to make Canadian political history.

On Monday afternoon, the day Diefenbaker was to speak, Roy McMurtry collared Brian Armstrong crossing the Château lobby. “Listen, we have a bunch of young people out in a motel in the east end of Ottawa and a couple of buses to bring them to the convention. Can you help?”

McMurtry and Armstrong took a taxi to the Eastview Motel. “We got all these young people who were YPCers and bused them downtown and got them into the front twenty rows of seats,” said Armstrong. They arrived early, ahead of others delegates, who later had to take seats further back in the hall, around the walls, or at the rear entranceway. The place was so jammed many could not get into the room.

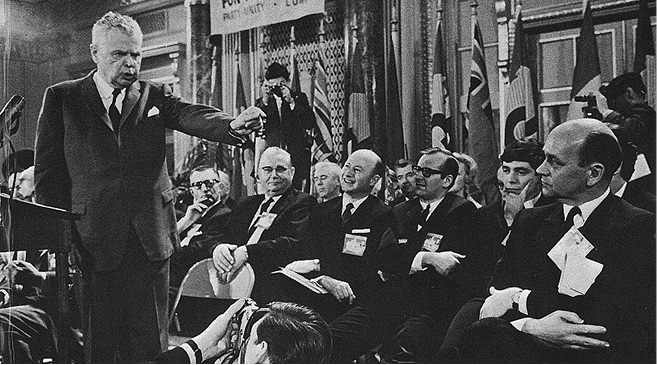

Dief’s speech showed how far he and the party had drifted apart since February 1958. Then, at an emotionally charged rally in this very same hall, a thousand jubilant PC partisans gave him a twenty-minute standing ovation when, as prime minister, he’d called a general election. Now, eight years later, the room, though again filled beyond capacity, was silent as he spoke, except for interruptions of jeers, and even boos.

“Is this a Conservative meeting?” demanded the old warrior, now at bay.

“Yes, yes it is!” arose strident youthful voices in reply, directly in front of him.

John Diefenbaker, who had come to the convention hall to subdue yet another wave of discontent about his leadership, stood impotent and humiliated, his head shaking uncontrollably from side to side. He had lost control of his party.

A well-orchestrated campaign that left nothing to chance had displaced voting delegates by students who remained seated when Diefenbaker made his grand entrance, and sat on their hands when he delivered lines expecting applause. Seated behind them, the majority of delegates, at least two-thirds of the total, watched the spectacle in mute apathy, on edge yet sickened by this fight.

Having failed in rallying the partisans, Diefenbaker turned to attack expressionless Dalton Camp, sitting on the stage, his arms gripped tightly around him, only feet away. Next to Camp sat Bob Stanfield, the other Tory premiers, and the senior party officials. “A leader cannot lead when he has to turn around to see who is tripping him from behind,” exploded Dief, pointing his outstretched arm and boney index finger at Dalton, making perfectly clear who the villain was.

“A leader cannot lead when he has to turn around to see who is tripping him from behind,” charged John Diefenbaker, pointing public accusation at party president Dalton Camp, on stage at Ottawa’s Château Laurier Hotel. The November 1966 drama, dubbed “the night of the knives,” was a galvanizing moment in Canadian political history.

When Diefenbaker’s troubling spectacle at last ended, Camp quickly sought private refuge in his fifth-floor room. “I felt sad. I wanted to get out of there. I’d never have believed it would be as bad as it was,” he explained later that night to the Toronto Telegram’s Ottawa bureau chief, Ron Collister. Dalton lamented how costly the “shattering experience” was going to be for Progressive Conservatives. Dief’s own speech, he said, had been “the turning point.”

John Bassett had gone directly to his hotel room, too, after Diefenbaker spoke, to dictate the editorial for Tuesday’s Telegram, proclaiming that the Conservative Party’s “Diefenbaker Years” were over. “They ended here tonight when the former prime minister’s appeal for continued support fell on deaf ears and was greeted time and again with boos and jeers.”

Privately, Bassett also revised his taunting assessment, made earlier in the year, about “the Eglinton Amateurs.” Seeing how Camp’s forces outman-oeuvred The Chief’s troops, the impressed Toronto publisher renamed them “the Eglinton Political Mafia.”

———

Meanwhile, the night surged with electric viciousness.

Not one of the party’s most seasoned veterans had experienced such a highly charged political meeting before. Many felt limp and hollow. Fights broke out. Diefenbaker grappled with agitated Quebec MP Heward Grafftey, who’d confronted him. Several women loyal to Dief used canes and umbrellas to batter James Johnson, the national director and Diefenbaker functionary who physically resembled his nemesis Dalton Camp.

Jack Horner and his brother, Hugh, both Alberta Tory MPs militant for Diefenbaker, roamed the Château Laurier’s hallways looking for trouble in the form of Dalton Camp or anyone remotely connected with him. The Horners, hard men with an even harder edge to their defence of Dief, saw PEI Tory MP Rev. David MacDonald and threatened to knock the Camp-backer’s teeth down his throat. Jack Horner took a swing at McMurtry, inspiring Roy to punch out the Albertan. Somebody landed a fist on Brian Mulroney’s face and, though not breaking his jaw, bloodied his nose. A university student referring to Dief as “the old S.O.B.” took a quick lesson in Tory Feuding 101, in the form of a blow to his head. The deeper wounds could not be so readily seen, nor would they heal as quickly as bruised and bloodied body parts.

Dief, outmanoeuvred and humiliated by Camp’s organization, did not for an instant contemplate resigning. Instead, he stood defiantly in a corridor by the main lobby and told reporters, slightly paraphrasing the “Ballad of Sir Andrew Barton,” with eyes flashing: “I am wounded, but I am not slain / I’ll lay me down to bleed awhile, / then rise, and fight again.”

The Chief then exited into the darkness of the November night, where wet snow on the ground was turning to slush. Fighting overwhelming odds had never daunted John Diefenbaker. Combat was his elixir. The more desperate the battle, the stronger he grew.

———

Next morning, McMurtry and Camp left the Château suite they shared with Atkins and, stepping out of the hotel for a brisk walk, hoped that exercise and fresh air might refresh them after the long night of heavy drinking, hard fighting, and deep feelings.

“What you are doing is right,” Roy said about Camp’s challenge to Diefenbaker’s leadership. “You should have an outstanding political future. But if you are successful today, you will likely never be forgiven by the Conservative Party.”

“The leadership of any great political party should be made subject to review,” asserted party president Camp, addressing Progressive Conservative delegates, because “no one has a right to continue as leader indefinitely and without accountability.” The backdrop sign is for his rival, former MP Arthur Maloney.

Despite delivering a speech that was far less dramatic than his opponent’s, after the secret voting was over and all ballots counted, Dalton was re-elected president of the Progressive Conservative Party. His edge was narrower than expected, 566 votes to Maloney’s 506. The jurors’ verdict reflected the backlash from delegates saddened by Diefenbaker’s shabby treatment, which Maloney brilliantly capitalized on in his speech: “When the Right Honourable John George Diefenbaker, sometime prime minister of Canada, enters a room, Arthur Maloney stands up!”

But with Camp reconfirmed as president, many Dief loyalists and Maloney supporters left Ottawa in disgust, or despondency, or disillusionment about party politics altogether. The more militant made a point of boycotting the rest of the proceedings. Given this change in the mix of delegates, the next agenda item, a motion to trigger a leadership convention, passed by a majority of almost a three-to-one. By secret ballot, delegates also adopted a resolution, 563 to 186 votes, expressing “wholehearted appreciation” for John Diefenbaker’s “universally recognized services to the party,” yet simultaneously directing the PC national executive to consult with the leader and then “call a leadership convention at a suitable time before January 1, 1968.”

———

Dalton Camp’s campaign cost between $20,000 and $22,000 and was paid by donations from a wide number of individual donors, most raised by Sinclair Stevens who’d also pulled together Camp’s Eglinton campaign war-chest, and Toronto lawyer Pat Patterson, Q.C., a Spade.

They’d limited contributions to $100 from any one donor so that, if required to disclose their sources, it would be clear Camp was in nobody’s pocket, and that he was certainly not a “front for Bay Street” as alleged by Dief spokesmen like Erik Nielsen. By contrast, all costs for Arthur Maloney’s campaign to support Diefenbaker were paid by the PC Party itself, using funds raised from oil companies, banks, and big corporations.

“There were so many ways to win that thing, so many arguments to be made,” Camp said about handling the leadership issue at the November meeting. “They just never made them.” Instead, as his biographer Geoffrey Stevens quotes Camp saying, “They just had their yahoos around. They were drunk, obscene, and they offended people.”

But the loyalists put their spin on events, too. A legend was born that the whole plot by Camp was engineered by James Coyne, former governor of the Bank of Canada, who’d left office under censure from the Diefenbaker government and become head of the Bank of Western Canada, in alliance with Sinclair Stevens. The loyalists took specific actions, too. Camp-supporting MPs were removed from Commons committees. A loyalty oath was circulated for all Tory MPs to sign. By the time it reached MP Heward Grafftey’s small Centre Block office, it carried the signatures of most PC MPs, both the willing and the intimidated. When handed to Heward, he tore the document to shreds. Alvin Hamilton convened a policy conference of loyal Dief MPs to make his point that the annual meeting had not dealt with any policy at all. Dief and his devout loyalists would be relentless in ensuring that anyone associated politically with the fiendish traitor Camp would, henceforth, be tainted goods themselves.

———

Three weeks after the tumultuous annual meeting, back in Toronto, Spade Chad Bark and Hal Jackman discussed Camp’s political future.

Bark wanted to raise a substantial fund and open a safe Tory seat for Dalton, either in rural Ontario or New Brunswick. The plan was to get Camp into the Commons where he’d be better poised to run for the leadership. Chad sought $100,000 for a substantial lump payment to entice a sitting PC member to give up his seat, salary, and pension.

In the months that followed, the project to create a by-election was aborted. The gambit proved a non-starter as 1967 progressed, because nobody could raise $100,000 for such an untoward purpose when PC fundraisers and donors were already draining themselves for the federal leadership candidates and to support Ontario’s PCs for an expected provincial campaign. Moreover, back-channel soundings with top Liberals indicated they saw no benefit to them in advancing Dalton Camp’s political career by calling a by-election. A deliberately vacated Tory seat could sit unoccupied a long time, damaging only the PCs. On top of all that, naked hostility to Camp in the Conservative caucus, from those who supported Dief, made the whole plan unappealing to Dalton. A by-election win would be easier to orchestrate once he was party leader.

———

Spade Ross DeGeer considered the 1966 Progressive Conservative meeting and Camp’s role in it “truly a watershed for the party and its membership, since it represented the democratization of the party.”

Dalton, after discussion with the Spades, understood he could no longer continue in the normal manner of president. On January 28 he met the party’s executive committee and senior officers in Toronto, explaining that his “unique involvement in the matter” meant he would not chair the convention committee or proceedings at the convention itself. Next day, two co-chairs were chosen instead, lawyer Eddie Goodman and Quebec MP Roger Régimbal. Another MP, Eugène Rhéaume, was named convention executive secretary. The co-chairs met with Diefenbaker in February and settled the convention date and venue: early September 1967 at Maple Leaf Gardens.