Chapter 30

The Remaking of Bob Stanfield

At the Westbury Hotel headquarters in Toronto, beginning Monday, August 3, Norman gathered his entire convention committee, just as he would begin each week until the convention started. Then they’d shift to daily breakfast meetings starting at 8.45 a.m. sharp.

“We had spectacular meetings,” enthused Bill Saunderson. Chairing them, Norman asked each person around the table, one by one, to update everybody on how their division was progressing. “It was exciting to see such good organization. It made us feel that we could win,” Saunderson said. Atkins was “teaching us how to run a campaign.” He not only had clearly defined systems, but “demanded everybody do things a certain way. It was the first time I had ever seen that kind of discipline in politics, where it was run like a war — real planning, uncompromising execution.”

They faced a large field of rivals, with Stanfield trailing well behind the other major contenders. Atkins stressed, “We not only have to be good at the convention, we have to be the best.” He, and they, repeated “be the best” like a mantra.

———

In August, as a run-up to the convention and implementing a proposal by party president Camp, who still kept his eyes on the larger picture of fashioning a contemporary Progressive Conservative Party, a thinkers conference to discuss and frame policy statements convened at scenic Montmorency Falls, downriver from Quebec City.

Some two hundred individuals began crafting statements of principle on matters vital to Canada’s future. These statements would in turn be considered at Toronto in September by four hundred policy delegates selected from every constituency, a status additional to being voting delegates at the convention. As the final step, the policy statements would be ratified by the full assembly at Maple Leaf Gardens. The PCs would not just have a new leader but a fresh approach for a revitalizing nation heading into its second century.

The Progressive Conservative “thinkers” comprised an impressive cross-section of party officials, federal and provincial elected representatives, sen-ators, university professors, and key players from private sector organizations. Canada’s French-speaking and English-speaking communities were represented by articulate, contemporary individuals. Thick binders of background readings on all topics were distributed early in the summer to all participants. The leadership candidates dropped in to make themselves part of the scene. An education minister, Ontario’s Bill Davis, chaired the policy sessions.

Quebec itself was astir on the political front. Across the province, the abstract notion of political separation was becoming a specific project, drama-tized by visiting French president Charles de Gaulle’s provocative open support for separatism. Just as Camp had this tension-fraught subject of Quebec nationalism broached at the 1964 Fredericton Conference, the PCs at Montmorency Falls discussed ways to embrace its sobering new expression. The Montmorency Conference adopted a straightforward statement: “Canada is composed of two founding peoples (deux nations) with historical rights who have been joined by people from many lands.”

That simple statement would have been objectionable only to Aboriginal Canadians trying to figure out where they fitted in their own country.

Montreal businessman and Union Nationale member of Quebec’s legislative council Marcel Faribault said the statement was a reasonable accommodation of all interests. Pressed by a throng of journalists, Marcel did his best to coolly explain how, in the French language, the sociologist’s word nation best expressed the contemporary reality of Quebecers. It corresponded with “people” when used in a sociological context — two peoples, deux nations.

At this juncture in the 1960s, English-speaking Canadians tended to view the quest of French-speaking citizens to preserve their culture and govern themselves according to the country’s Constitution in one of three ways: sympathetic understanding, mute indifference, or hostile resistance. John Diefenbaker was not only in that third category, but one of its leading exponents. From Ottawa, he thundered in outrage.

Dief did not use the words “founding peoples” adopted at Montmorency, but substituted his own translation of deux nations as “two nations,” meaning countries not peoples, deliberately changing the express wording of the statement. He then intimated that the PC Party was supporting, either through a surreptitious plot or by innocents duped by Quebec nationalists, separation of Canada into two countries. Marcel Faribault was the antithesis of a Quebec separatist. There was no “plot.” But for Dief, reality was not relevant.

He was vindictive. He was scornful. He was untruthful. He played with semantics in opposing the simple Montmorency statement of conciliation and clarity because The Chief, finally, saw a glimmer of hope for himself. Still leader of the Progressive Conservative Party, he would identify himself in a new role, warning Canadians about the peril of separation, leading the country back from the brink, and identifying that national quest with the necessity of his own continued leadership.

John Diefenbaker would foment a crisis about “One Canada.”

———

Stanfield, on the other hand, did not have a strong presence. Nor did he even have the sort of compelling looks that attract attention, a problem his own supporters had to contend with. Bob Stanfield was “not the most photogenic of people,” one blue machine insider lamented to another. Camp himself had said, after first meeting the Nova Scotian and evaluating his attributes as a candidate, “at least he’s not handsome.”

But something strong had to be projected for the premier’s image if he was to stand apart from, and surpass, almost a dozen other candidates in the increasingly crowded race. Atkins asked a creative artist at the agency to make a line drawing of Stanfield’s face. “By using the line drawing,” he said, “you could give Stanfield’s character strength that did not come through in a photograph.”

The result was more abstract, and dramatic, presenting not Stanfield’s human limitations but his symbolic essence, the way popular posters in the ’60s celebrated the look of Che Guevara, Marilyn Monroe, Bob Dylan, and others who personified something larger than themselves.

Bob Stanfield had been a direct, simple man who answered his own telephone in the premier’s office, strolled out to meet visitors, and liked gardening “because flowers are beautiful and don’t talk back.” Now he was Robert L. Stanfield, whose features were as strong as rocky Nova Scotia itself. His essence distilled by abstraction, he was no longer a person but a persona, his social distance and apolitical nature no longer liabilities but qualities placing him above the jostling fray, the rare phenomenon of a true leader emerging from among the people.

The line drawing image was used for all the campaign graphics, on posters and pamphlets, buttons and bags. “At the appropriate time during the floor demonstration,” beamed Ross DeGeer about the convention show he was running, “a huge banner will drop from the ceiling of the Gardens, with the Stanfield drawing on it — very dramatic!” That kind of imagery and use of graphics, an integral aspect of Atkins’s plan for winning, became an essential part of the blue machine’s complete make-over of Bob Stanfield.

The machinists, knowing that political events do not unfold like a natural blossoming flower on a woodland hillside, but are the product of deliberate grafting and forced growth in a hothouse atmosphere, were planning to seize the high ground and convert their improbable candidate into a front runner in a variety of ways.

Camp, whose strategy proceeded from his belief that the convention had to be won in Toronto, insisted Nova Scotia and other pro-Stanfield Maritime delegates arrive early and register right away, to have plenty of dedicated workers in play from the outset. Supplementing these focused forces were know-ledgeable locals, Atkins’s “Eglinton Mafia.” When delegates began arriving at Toronto’s downtown hotels, they landed unmistakeably on Stanfield turf.

Other campaigns had noted the convention’s starting date, so their teams could start putting up signs then. But by the time volunteers for Hees, Fulton, Roblin, and Fleming appeared at the Royal York and other convention venues, they encountered a profusion of Stanfield posters and signs. There was little space, if any, for them to affix their slogans, banners, and candidate photos. Certainly, all the best spots, with long sight-lines and good elevation above the crowds, were taken. It was a clever blow, making these supporters feel behind even before things got started.

This opening psychological victory was then followed by triumph over the competition in another dimension. All lobbies and corridors of the convention hotels were populated with delegates committed to Stanfield who, after checking in early and being issued Stanfield buttons, had been requested, on Atkins’s instructions, to cluster around any television cameras they saw.

Reporters with the national TV networks, incorporating interviews of voting delegates in their early convention coverage, revealed from day one that Robert Stanfield had overwhelming support. Voting delegates were the ones who mattered, after all, and they preponderantly supported him. It was as if the reporters had tapped into an undiscovered groundswell.

This was real news. It quickly spread with its own momentum. The Nova Scotian was the powerhouse candidate nobody had previously realized.

———

At the first convention campaign meeting Atkins convened in Toronto, he took up Ross DeGeer on his offer “to bring some people together to run the floor demonstrations at Maple Leaf Gardens.”

Able to draw on his extensive network in the Toronto Junior Board of Trade, DeGeer had readily available a group of some three hundred young Toronto businessmen and entrepreneurs. This potent force of energetic, talented individuals in their late twenties and early thirties was ready, willing, and exceedingly able. Looking for new adventure, they were a campaign organizer’s dream.

DeGeer was responsible, too, for a huge competitive advantage he and Atkins quickly added to the Stanfield campaign. Ross, just returned from a Junior Chamber of Commerce convention in the United States, had been awed by “the effective use of telephones on the floor of the convention and in delegate tracking.”

He and Atkins acquired the new technology for their operations. This, said DeGeer, “gave us a leg up because we could follow the activities of certain key opponents and their staff and their supporters and flag that information immediately back to Atkins and Camp and others who needed to know.” The Stanfield campaign not only made unprecedented use of two-way telephones at the Gardens, but applied this innovation “to every aspect of the campaign.”

Nothing was left to chance when it came to communications. Norman’s emphasis, in every campaign, was “people and communication.”

Stanfield organizers were issued light-blue jackets, making them readily identifiable to each other across a crowded room, on the street, and in the Gardens. This further intimidated the competition, who saw a couple of hundred such blue-clad individuals sprinkled everywhere, passing information and instructions to one other by mobile telephones; they realized, yet again, that they were up against superior force. By the same token, as the former soldier Atkins understood, members of his political machine wearing their pale-blue uniforms became united in bond of identity and elevated in status. The women were also issued black top hats, which Norman felt added panache and helped shorter females stand out more readily in the crowds.

A campaign song was written and performed in many venues; fitted to the well-known tune “This Land is Our Land,” the lyrics extolled “Stanfield, the man with the winning way.” A press trailer was set up at the northwest entrance to the Gardens; manned by press-savvy spokespersons it provided reporters any information they wanted about Stanfield or his campaign, morning, afternoon, and evening. A lively tabloid newspaper was also published every night of the convention by the Stanfield team. It was filled with engaging pictures taken by a team of four photographers, news written by three reporters, all edited by Jack Wilcox and printed at 4:00 a.m. in Brampton and distributed by 7:30 a.m. under the doors of delegates in all twenty-four hotels where they were staying. Everyone would see the PC event through Stanfield eyes and understand the week’s complex activities according to pro-Stanfield interpretations.

Even “spontaneous” activities — a placard-waving demonstration, a cluster of delegates in a hotel lobby breaking into the Stanfield song, a throng forming around Bob and Mary Stanfield as they moved from one place to another — were planned in detail, in advance. Every hour of each day was accounted for with purposeful performance by the Stanfield organization, but reviewed daily to be changed as required in response to new circumstances.

The four main hotels — the Royal York, King Eddie, Lord Simcoe, and Westbury — had popular Stanfield “hospitality suites,” manned by Stanfield-voting delegates as greeters who pushed their candidate in friendly ways and offered an extensive bar, food, and non-alcoholic beverages. These busy venues were closed whenever official convention proceedings got underway, to ensure Stanfield’s campaign was never blamed for keeping delegates from formal sessions of important business.

Selling Bob Stanfield was the business at hand, because the Nova Scotia premier stood third, perhaps fourth. The large squadron of pro-Stanfield delegates, circulating to woo undecided voters and calmly seek the eventual support of delegates committed to other candidates, were under strict orders from Atkins, relayed from Dalton, to remain low-key. They must only talk up Stanfield’s personal qualities and his track record as a winner. The Maritimers were, as reporter Fraser Kelly noted, “infectious and convincing persuaders” when talking about the worth of Bob Stanfield, true believers in “his sincerity and political integrity.”

There was to be no pressure, though. There would be no mention of another delegate’s candidate being eliminated as the rounds of balloting advanced. Stanfield was just to be the respectable, easy choice when the time came.

———

The most important communication of all would be Stanfield’s own.

By the summer of 1967, Bob Stanfield and Dalton Camp had honed their speechwriting regime to a high art that essentially had two dimensions. First was their shared outlook on most major issues: the legitimate aspirations of French-speaking Canadians, the need for governments to take an active role in economic development, the scandal of people lacking work and money in a prosperous country. The second was Stanfield’s ready acknowledgement that Camp could express ideas with a potency he was incapable of, balanced by Dalton’s knowledge that craggy, unemotional Bob could convey his words with a public authority he lacked. An odd couple, they were ideally matched.

Camp, ruefully accepting his status as a villain nobody wanted to be seen with, continued operating through the summer from Robertson’s Point, a setting conducive to the personal restoration he needed anyway. In addition to the strategy and plans he and Norman discussed daily by telephone, Dalton’s main role would be to write speeches for Stanfield that set him apart by catapulting him to the forefront as the only candidate with a true leader’s vision for the country’s future.

Camp’s apparent recovery from his deep emotional bruising took the form of sublimating his own quest for the PC leadership into Stanfield’s. He had, after all, made a sustained effort to persuade the premier to run, despite knowing he felt uncomfortable at the prospect. And Stanfield’s heart-wrenching change of mind, in some measure, turned on what could happen to the national PCs, and hence the country, if Dalton ran: at best becoming leader of an irrepar-ably divided party, at worst dividing the party while becoming more politically crippled himself in the process, perhaps even being physically harmed because feelings against him were so intense. Dalton got this. He’d do his uttermost to help Stanfield, despite his unresolved deeper emotions. Writing some of the best speeches of his life, Dalton would now gift his candidate with the words he’d have spoken himself, had he been the one at the podium.

Because Atkins insisted on complete, accurate, and timely information about everything, he learned, as soon as it had been decided, that an opening evening in the convention would feature policy presentations by each candidate to the four hundred policy delegates. Dalton was informed, and began preliminary work on a concise, hard-hitting, forward-looking outline of Robert Stanfield’s political philosophy, policies, and programs.

When Roy McMurtry observed that “Stanfield was clearly not prepared for the aggressive central Canada media,” Norman discussed the problem with Dalton, who crafted a self-effacing and humorous speech for the candidate to deliver to a luncheon organized by the Stanfield campaign for the news corps and help win them over.

Most important of all would be the main convention speech each candidate delivered to the full assembly and a national television audience at the Gardens. For this one, Camp would expend extraordinary effort, because it also had to confront the inflammatory spectacle his nemesis John Diefenbaker was making of “two nations.”

———

On Labour Day, Bob and Mary Stanfield arrived at the weekend farm of Don and Ann Guthrie, near Moonstone north of Toronto, where they were to stay for the next three nights, before heading down to the convention on September 4. The Stanfield’s whereabouts was kept strictly secret, making the news media more interested and the other candidates more apprehensive.

The candidate was being refreshed, after travelling twenty-seven thousand miles to meet PC delegates all August, and getting focused on the intense week ahead. For two days he and Mary relaxed. Then they were joined by Camp and Atkins, who had come to prepare them for the crucial days to come, one discussing the content of the speeches, the other the nature of the organized events. Sunday evening and Monday morning were consumed with discussion. Then Dalton and Norman headed south to Toronto, into the rising tempo of the Tory convention and Atkins’s third-floor suite at the Westbury, the party’s president camouflaged by sunglasses and hat.

That evening, still secluded in the suite, Camp drafted the speech, with the help, as prearranged, of Quebec’s Bernard Flynn and Queen’s University political scientist George Perlin. Bernard guided the writing of the section dealing with French Canadians, and also translated the passages Stanfield would speak in French. Next morning, Tuesday, Camp was taken by one of the Spades unnoticed up a service elevator to Stanfield’s sixth-floor suite at the Royal York, where the two men revised the text. After those changes were made, Stanfield again tweaked a few words, marking the pages on his hotel room’s small desk with his fountain pen.

That evening, having rehearsed repeatedly, Stanfield went downstairs relaxed and fully prepared. He entered, with a small entourage, the Royal York’s concert hall where a long table had been set up for the candidates to face the many rows of seated policy delegates and some three hundred pro-Stanfield supporters whom Camp and Atkins had urged to arrive early and occupy all available space. For Stanfield himself, this was the moment to make a strong first impression.

Bob edged his way along the riser behind the other candidate’s chairs to his seat. He paused to greet ebullient and well-tanned George Hees, quietly commenting, “You look a little pale, George. Are you feeling alright?” As he continued down the line, Hees visibly deflated.

When he passed Duff, the first time they had seen each other in months, he first just nodded a greeting, but then added, “This is a pretty important night for all of us, I guess.” Roblin was shaken. He’d been wrongly informed by his campaign team that he was only to make a brief opening statement, friendly and easy, then field specific questions from the policy delegates — no sweat because he knew his stuff. Roblin looked with alarm across the crowded rows of delegates waiting to narrow their choices for leader, the first time they’d see and hear the candidates in a common setting, each delivering his major policy statement to the national PC convention. Whereas Stanfield practically knew his thoroughly debated and well-crafted speech by heart, Roblin began hastily scribbling a few top-of-mind notes on a pad.

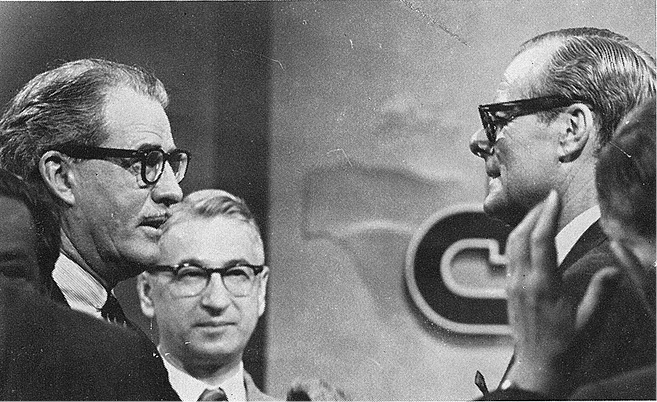

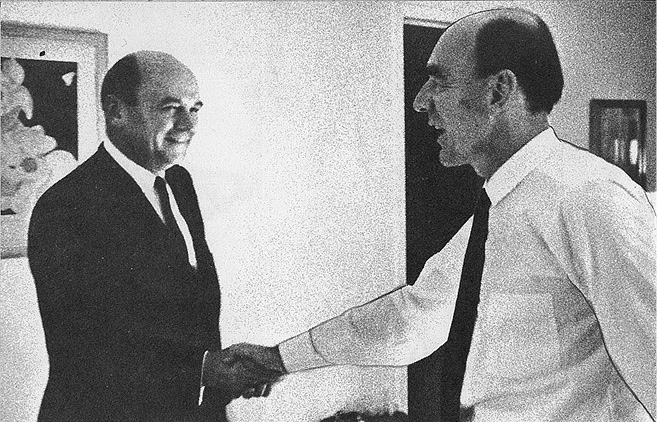

PC leadership candidate George Hees, left, hears John Bassett tell him he’s switching his influential support as Tory publisher of the Toronto Telegram to Robert Stanfield. The newspaper carried front-page editorials by Bassett that helped sway many delegates and build momentum for the blue machine’s campaign to elect Nova Scotia’s premier.

By the time the session was over Roblin, with his rough improvisation, had offered a bunt that rolled foul. Stanfield, with Dalton’s finely honed message, had hit a homerun. Camp, enjoined to keep out of sight and unable to witness the candidate’s stellar moment, happily chose instead a quiet dinner at a posh Yorkville restaurant with Linda.

The galvanizing impact of Stanfield’s brief speech could not be exaggerated. Its resounding triumph made all other contenders pale in comparison, establishing him as front runner. With the heavily pro-Stanfield audience, he’d been warmly applauded when he stood to speak, been interrupted by applause throughout his brief remarks, and was the only one given a standing ovation at the end.

The media were impressed, both with his speech and the response to it.

Roblin’s campaign team, which had not yet gelled, became rattled. They’d thought their main competitor was George Hees, not realizing, as the Toronto Telegram’s Fraser Kelly wrote, “the impressive power of the Stanfield organization.” But they were beginning to appreciate, at last, the threat posed by “a supercharged, smooth-running machine with Dalton Kingsley Camp oiling the gears.”

Just how smooth was demonstrated overnight. Telegram publisher John Bassett wrote a front-page editorial switching support from Hees to Stanfield after their policy speeches. By 7:00 a.m. next morning, Atkins’s Eglinton Mafia had slipped a copy of the Tely’s early edition under the hotel doors of every PC delegate, in all twenty-four hotels.

Said Winnipeg South MP Bud Sherman with the Roblin campaign, “We didn’t wake up in time to the fact we were working against a tremendously polished, sophisticated, intuitively intelligent organization.” Privately, Sherman rued the fact the blue machine could have been backing his candidate, had Duff not dithered.

———

Stanfield’s second speech, to the media, was just part of busy Wednesday’s “fun day” of campaign activity, when he earned laughs with Dalton’s lines at a noon-hour press luncheon consisting of cocktails, clam chowder, and conviviality.

Stanfield was at ease through Wednesday, realizing, as did Atkins and Camp, that their campaign was taking off. That night, the blue machine pulled a coup entertaining and wooing delegates by booking the Royal York’s massive Canadian Room for a party that started at 10:05 p.m., just five minutes after a reception hosted by convention co-chairs Eddie Goodman and Roger Régimbal ended at the same location. More than two thousand delegates simply re-entered the hall for upbeat down-home music performed live by Don Messer and His Islanders, alternating with vibrant sets by the Quebec band Les Cailloux, all accompanied by free drinks instead of the one’s they’d been paying a dollar for at the prior reception. Bob and Mary circulated the room twice, before the party wound up at 1:00 a.m.

———

John and Oliver Diefenbaker arrived at the Royal York Wednesday morning, September 6, and ensconced themselves in the vice-regal suite. The party’s leader wasted no time creating a crisis atmosphere for the convention, commenting on “two nations” to the reporters who swarmed him.

He challenged the concept of the Montmorency policy statement, but pointedly left unclear whether he’d come to town to bust up the PC convention or be a candidate to succeed himself as leader. Thursday he’d address the convention, and the country via television, from Maple Leaf Gardens.

By Thursday, the Roblin troops, noted Ron Collister of the Telegram, “were reeling under the impact of the Camp-Stanfield machine.” They vowed to fight back with a lot of hoopla and noise. By contrast, Norman and his team decided to make Thursday “a quiet day,” since a blatant Stanfield demonstration on this trying day for Dief could provoke an antagonistic response from his sympathizers, who understood that Stanfield was backed by Camp, the ultimate villain of the piece.

“The convention is essentially a serious business,” said Atkins, “and that will be our theme today.” Atkins felt tactically that a shift in tone would be appropriate. Intelligence reported at his breakfast session indicated that Roblin’s supporters “would be trying to plan some extra demonstrations to gain back lost ground.” So, Atkins decided, “a change of pace by us will confuse them.”

On this day for tributes to John Diefenbaker, followed by his long-awaited speech, the Roblin forces busily stirred up all the action they could, while Stanfield and Camp stayed out of sight and quietly worked on his speech for Friday. Stanfield’s main campaign activity, in accordance with this day’s tactic of deliberate quietude, was to be first candidate to appear at Maple Leaf Gardens that evening, calm and dignified, and then to sit impassively for television cameras in his reserved seat, and quietly witness John Diefenbaker’s performance.

When at last he spoke, The Chief took strength from the huge assembly of fifteen thousand people in the Gardens and intense heat, made hotter by glaring television lights. Whatever he said to the massed delegates would also be carried in this moment of drama to millions viewing their TV screens or tuning in on their radios. John Diefenbaker delivered one of his best addresses, almost a textbook classic. It was designed to divide the Progressive Conservative Party by asserting that its “two nations” policy would split the nation in two. “I couldn’t accept any leadership that carries with it this policy that denies everything that I stood for throughout my life.”

He’d said his piece, erecting “two nations” as an artificial issue. It was “the desperate attempt of an old man trying to keep from being fired,” said one reporter, with bleak realism.

It might have been credible for a politician to champion “One Canada” if he evinced a sympathetic understanding about the importance to the country of Quebecers and French-speaking Canadians generally. Leading French-Canadian nationalist Henri Bourassa, early in the twentieth century, had defined such a view of national unity when he expansively declared, “All Canada is my home,” refusing to be sequestered in a cultural ghetto and rightly laying claim, as every Canadian should, to the whole country, while respecting inescapable, valuable differences between the diverse peoples who dwell in it. John Diefenbaker’s “One Canada,” however, did not embrace Bourassa’s optimistic realism. Dief campaigned for his party’s leadership in 1956, and won it by snubbing French Canadians. The following year, he campaigned in a general election, and won it by writing off Quebec as a Tory wasteland not worth the effort or expense. The year after that, fifty MPs from Quebec joined his Progressive Conservative national caucus only to find a prime minister uninterested in their talents and unresponsive to their political demands. By 1965, his own dispirited deputy leader in Quebec, Léon Balcer, asserting “the Conservative Party of John Diefenbaker has no room for French Canadians,” had quit.

For months John Diefenbaker had held his party and the country in suspense about his future, while trumping up a divisive issue about “two nations.” Delivering his major address to the convention, the leader ramped up more dramatic tension but still left his options open.

The early steps Diefenbaker had taken as PM, appointing Georges Vanier Canada’s first French-Canadian governor general, introducing simultaneous translation in the House of Commons so French-speaking and English-speaking representatives could understand one another, and printing bilingual family allowance cheques were constructive, for their times, though limited. Even these initiatives were politically nullified by the overarching battle he’d begun to wage: rallying those mutely indifferent or hostile to French-speaking Canadians, fomenting a fearsome political storm among their English-speaking compatriots by fabricating a shoddy issue out of his politically mischievous linguistic distinction.

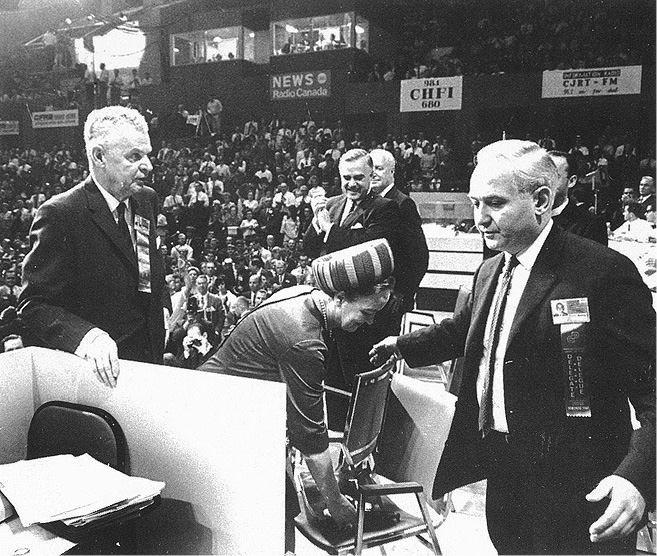

John and Olive Diefenbaker at the Gardens in September 1967, with convention co-chair Eddie Goodman guiding them unhappily off stage. Behind Olive is Ontario premier John Robarts, holding his hands but not applauding, and behind him, former premier and prior national leader George Drew, looking on with his hands at his side. The arena was jammed with delegates, Tory observers, and news media perplexed about Dief’s next play.

John Diefenbaker’s attack on “two nations,” when coupled with his lofty-sounding appeal for “One Canada,” especially in Centennial Year, imparted specious nobility to old bigotries. But it was his best shot, as he imagined the scenario, for remaining party leader and returning to the prime minister’s office.

The next day, just moments before the 10:00 a.m. Friday deadline for filing candidate nominations, television personality Joel Aldred, who’d been working in support of Dief, rushed with the signed papers and presented them to Lincoln Alexander, the convention’s chief election officer.

The unyielding Chief was a candidate for his own job.

———

For the crucial floor events at the Gardens, DeGeer had pulled together “a very powerful organization,” whose core group included Bill McAleer, Hal Huff, Gordon Petursson, and Tom MacMillan.

Stanfield’s campaign was the only one with phone communication. Roblin’s “thin air” campaign, like the others, hadn’t acquired such capability. Fulton’s campaign had specifically rejected new technology for networking, instead relying on floor workers’ personal contact, Lowell Murray having ruled against walkie-talkies because “they could be jammed.”

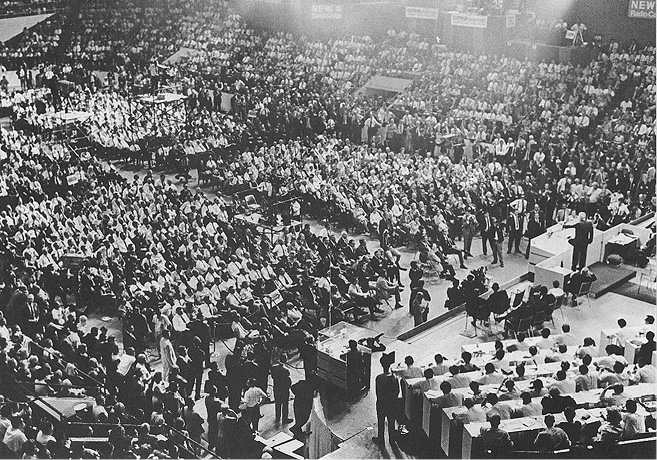

The DeGeer-Atkins mobile communication system had facilitated a precision arrival of Bob and Mary Stanfield at the Gardens on voting day. The couple walked up one street, with a large marching band, toward the arena at the corner of Carlton and Church; their arrival was smoothly synchronized to coincide with the arrival of a second large marching band coming along an adjacent street — each group pulling their own crowd of onlookers, both troupes meshing seamlessly into a jubilant large force heading on into the building and its waiting throng of cheering Stanfield supporters.

Meanwhile, Duff and Mary Roblin found themselves left standing in the Westbury’s parking lot when their small band, on predetermined schedule but not cued for last minute changes, left while the busloads of their supporters mistakenly went directly to the Gardens. The Roblin campaign had plenty of activity, but lacked the exquisite coordination of Atkins’s machine.

In the Gardens, the Stanfield team’s competitive advantage included the two telephone-type lines, installed by advanced-electronics technician Jim Pearce. DeGeer ascended to Foster Hewitt’s broadcasting gondola, high above the Garden’s floor. Holding a pair of binoculars to his eyes with his left hand while speaking into his mobile phone in his right, he was able to transmit intelligence instantly to eight key operatives at four locations around the voting section. A second high-altitude spotter in the press box added to this flow of timely updates on the movement of key personnel from all campaigns, critical when candidates were defeated and their delegates came free to vote for Stanfield. Stanfield poll chairmen wore black top hats with large white numbers, on top and four sides, so the spotters could direct the Stanfield floor men with headsets to relay information to one or another of them specifically. These phone lines also connected to Stanfield’s private room at the Gardens, where Flora MacDonald received calls, screened info, and via her “hot line” relayed key updates to Dalton Camp and Finlay MacDonald in the Stanfield war room at the Westbury.

Roy McMurtry, equipped with the blue machine’s two-way communications gear, and Norman Atkins, wearing a rose, are ready for action on the convention floor at Maple Leaf Gardens. All the Spades had key roles in the campaign to make distant-choice Stanfield the new PC leader.

———

The party compiled lists of voting delegates and provided them to candidates, but the ability of each contender’s organization to use the information varied.

For Dalton’s 1965 campaign in Eglinton, Norman quickly saw the usefulness of Len Reilly’s tracking system when he unveiled it and turned over his recipe boxes of index cards. The MPP’s painstaking method of recording details on every voter with whom he interacted, and codes to indicate key information unique to that person, became the basis for organizing and tracking Dalton’s campaign support. The same method had been adapted by Atkins and Flora MacDonald for a nationwide tracking system of PC delegates and their voting preferences, identifying undecided voters to help Stanfield workers focus attention on the most fertile possibilities for expanding his support, and also identifying which delegates were backing candidates who’d have to drop out and thus warranted special missionary attention.

Flora spent the summer in Halifax organizing an extensive system of file cards: one for each delegate. In September, she transported her priceless records to Toronto and, with Norman’s collaboration, set up her delegate tracking system in the Westbury. As the week progressed and undecided delegates began to narrow their choices, their cards had been updated. Other campaigns marked up the original party lists as best they could, but their intelligence was haphazard and follow-up more sporadic. The delegate-tracking committee of Stanfield’s team narrowed its gaze to winning the convention, one voter at a time.

A week before voting day, Flora had determined with precision at which of the twenty voting machines each of the 2,256 delegates would make their choice. Roy McMurtry, who with Parry Sound-Muskoka MP Gordon Aiken was running the extensive Stanfield floor operations, had this list days in advance. “As a result,” he said, “my poll chairmen and scrutineers were able to have the best persons available at each machine to help persuade support.”

———

Anyone thinking John Diefenbaker would not continue to fight, as he always had over many decades against great odds, did not know him.

A battle at the Gardens was the drama Dief craved. Since his flailing humiliation at the Château Laurier in November, he’d kept everyone on edge about his intentions. Camp was far from alone in his apprehension that The Chief would be a candidate and, somehow, remain leader. So many candidates might split the opposition to Diefenbaker and, in one of those crazy convention outcomes, allow him to hold on.

Dief’s dream, fostered by advisers like Gordon Churchill and David Walker, was that on the first ballot he’d get upwards of 1,000 votes from the 2,256 delegates, a mixture of The Chief’s loyalists and others wanting to express a final “thank you” with their first ballot, before getting down to selecting his successor in subsequent rounds of voting. Their fantasy was that getting close to a thousand votes could translate into a surge to return to John George Diefenbaker.

The hard edge to this plan, and Dief’s justification for trying to withstand the greatest challenge any incumbent Canadian party leader had ever faced, was the anti-Quebec, anti–French-Canadian undercurrent he sought to foment, and then exploit, with his “two nations” ploy. On Friday, the crisis was escalating, but nobody knew how grave it might become.

Diefenbaker told reporters, “I remain unchanged and unswerving in my opposition to the two nations concept.” Gordon Churchill stirred around, building up tensions. It was imperative, he asserted, to reject the policy committee’s recommendation to adopt the two founding peoples (deux nations) statement, to have it “openly debated and voted on at the Gardens by the full convention,” or it would provoke “the crisis to top all crises” because Diefenbaker would lead a massive walkout.

The work of politicians is to solve a crisis, and because Toronto was awash in Tory politicians, a plan to appease Diefenbaker was desperately hammered out behind closed doors. The policy would be tabled, rather than adopted. Bill Davis as policy chair, ready to address the convention about the importance of the “two founding peoples (deux nations)” statement, had to delete those paragraphs and use his ten minutes to say, essentially, nothing.

With Dief appeased, the convention could get on with the candidate’s final speeches. Roblin was convinced The Chief would make a short speech then withdraw as a candidate. He tried to bet on it with reporters.

———

In his convention address at the Gardens, Stanfield said English Canadians must accept that French-speaking Canadians “have the right to enjoy their cultural and linguistic distinctiveness. This right was clearly accepted by the founding fathers as a basic principle of Confederation,” he continued, “and it is our responsibility to see that it is given meaningful expression.”

Behind that reference to a principle of Confederation, which resonated profoundly in the year when Canada was celebrating its hundredth anniversary, was the fact that during the Second World War the Government of Canada had temporarily, as part of the war effort, entered provincial jurisdictions of authority and acquired provincial fields of taxation. After the war, the new sense of nationhood across English-speaking Canada did not impel a return to the earlier state of affairs. Indeed, the governments of English-speaking provinces agreeably acquiesced in Ottawa’s drive to expand its programs and introduce new services in fields of provincial jurisdiction. Quebec’s government stood apart, resisting federal intrusions into its areas of responsibility. The “new demands” of Quebec nationalists in the 1960s were the most conservative of voices in the land, insisting that Ottawa respect the Constitution of 1867.

That is what Stanfield understood and sympathized with, as did Camp. It was what Dief misconstrued and opposed.

John Diefenbaker sought to convey his special affinity with Canada’s first prime minister, John A. Macdonald. But the links were more coincidental than substantial. On fundamentals of nationhood, Dief never adhered to Macdonald’s teaching about, or shared his sympathetic understanding of, French Canadians. “Treat the French Canadians as a nation,” Macdonald preached in 1856, enunciating his core principle, “and they will act as a free people generally do, generously.” Macdonald knew harmony between French- and English-speaking Canadians was vital for everything else, from constitutional stability to political success of nationhood. He believed building a strong Canadian “nation” while simultaneously treating French Canadians as a “nation” did not create a conundrum, the way Dief pretended, because Canada’s Constitution never required uniformity but it did protect minority rights.

The Montmorency statement, entirely consistent with Macdonald’s formula for nationhood, was misconstrued by Dief, who equally ignored Sir John A.’s admonition that politics required “an utter abnegation of prejudice and personal feeling.”

———

In Saturday’s first round of balloting, only 271 diehards supported The Chief.

He ranked fifth, after Stanfield, Roblin, Fulton, and Hees. With the second ballot, he fell to a paltry 172 votes. Dazed by the disaster, with Olive weeping, he huddled in shock with David Walker and Gordon Churchill, then blurted, “That’s it. It’s over.” He wanted to withdraw, but by now the third ballot was underway, in which his support dropped to 114 votes.

The leader’s humiliation, devastating in scope, provided a precise measure of the large bubble of unreality in which the former prime minister had been living. Dalton’s earlier memos and conversations with him, diplomatically aimed at guiding the old man to accept that it was time to depart with dignity, had never worked. When it had dawned on Camp that the leader would never step down peacefully of his own volition, he’d shifted, in light of his larger responsibility to the party as its president, to press for leadership review, which had brought them inexorably to this September showdown in a hockey arena.

In the important opening round of balloting, when relative positions were established, Stanfield gained the advantage because Diefenbaker’s candidacy drained votes from Roblin. His 519 votes placed him measurably ahead of Duff’s 347, while the Manitoban and Davie Fulton were in a virtual toss-up for crucial second spot. The British Columbian was chagrined, after his long and costly campaign, to land just five votes behind late-starter Roblin. Those close to him saw Fulton’s face turn white.

Of the other major contenders, George Hees stood fourth with 295 votes. As the rounds of voting continued, and the lowest candidates dropped out, Stanfield stayed ahead. Once Dief was out, with his prominent supporters Gordon Churchill, David Walker, and Joel Aldred moving over to visibly support Roblin against Camp-backed Stanfield, Roblin closed the gap, with just ninety-four votes separating the two premiers. Fulton’s and Alvin Hamilton’s delegates would now be forced to choose one of them. Both were western Canadians, and their delegate base might reasonably be expected to have greater affinity with Roblin.

But back in July, when the field of candidates was shaping up, Camp had concluded that though Fulton could not win he would be a significant player in the end-game. A key part of his campaign strategy, as a result, had been to patiently woo British Columbia delegates. He dispatched J. Patrick Nowlan, son of George and now a PC MP from Nova Scotia, to the West Coast to spend weeks quietly attracting support for Stanfield. It was an inspired choice, because Patrick had lived in British Columbia, practising law, running as a provincial PC candidate for Fulton, and establishing a network of Tory friends. At the convention, McMurtry remained in close contact with Fulton organizer Brian Mulroney. Outreach to those around Fulton also included organizers Joe Clark and Lowell Murray. With constant attention from Atkins, an understanding had been established that, if Fulton couldn’t win, he’d come to Stanfield.

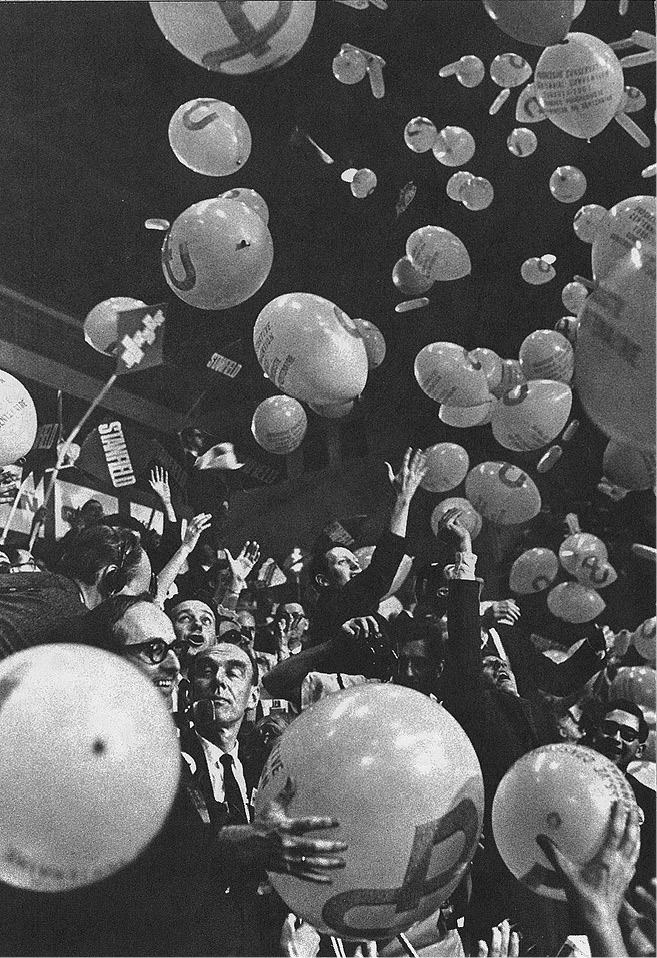

Stanfield, Nova Scotia’s taciturn premier, when announced as winner of the PC leadership convention, raises his eyebrows in a slight expression of surprised apprehension. The deluge of balloons offered an apt touch to the blue machine’s remarkable campaign.

Back in his Royal York Hotel room after being elected Progressive Conservative national leader, Robert Stanfield had a caller sometime after 2:00 a.m. Dalton Camp, who’d been kept in hiding, arrived via a service elevator to congratulate Stanfield and heave a sigh of relief over the outcome.

Yet when Davie was forced out and the final ballot loomed, he was too dispirited to make the traditional walk over to Stanfield. After conferring with his top organizers while Duff and his key political assistant, Joe Martin, waited nearby to meet with him, Fulton said he would personally support Stanfield but freed his delegates to go where they wished.

Alvin Hamilton chose to not openly support either man.

All the while, Stanfield’s floor workers had been seeking out Fulton delegates and handing them Stanfield badges. The space between the seats for Fulton and Stanfield was jammed with swarming delegates and pressing reporters. McMurtry relayed the message that Fulton would support Stanfield, but he’d have to come to him. Walking the fifty feet to Fulton’s box, Stanfield raised his hand, claimed his delegates, and got 54 percent of the votes on the final ballot to Duff’s 46 percent, a ballot count of 1,150 to 969.

The Conservative Party had often been led by federal parliamentarians who’d become prime minister, and it had twice been led by premiers whom national victory eluded. Now, for a third time, the Tories had chosen a provincial politician, thanks to a come-from-behind campaign that astonished just about everyone.

Back at his Royal York suite in the wee hours of the morning, sitting on a sofa in shirt sleeves and sock feet talking over his win, Stanfield heard a knock on his door. Looking up, he saw coming in the man who’d orchestrated his campaign from Robertson’s Point, a farm at Moonstone, and a room in the Westbury Hotel.

Stanfield rose and in two strides was shaking Dalton’s hand.

“Congratulations,” beamed his strategist and speechwriter. “It was great!”